Features

New century, old story: War ends as social tragedy, continues as political farce

(Fifty years after 1971: Concluding Part)

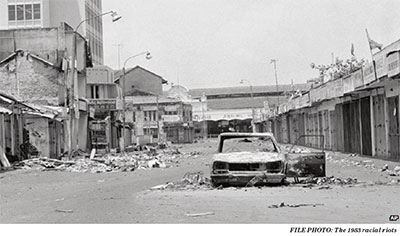

The violence of 1983 impacted the Tamils indiscriminately and directly led to the emergence of the Tamil diaspora. On the other hand, the backlash to 1983 from outside Sri Lanka, especially the West and human rights organizations, may have been a factor in the energization of the JC school after 1983. The UNP government of the day wholly owned the 1983 disaster and deserved a great deal more than whatever blame it got and wherever it came from. JC was opposed to the UNP government’s open economy swindle and its cultural sellout, and it resented the government’s cunning approach to the Tamil national question. That was to parley with Tamil politicians in secret, and organize violence against Tamil civilians in the open. When 1983 went out of control, the backlash was not only against the government, but besmirched the entire Sinhalese society, including those who were revolted by the violence and others who were intractably opposed to the government. And there were backlash echoes from different fragments in the Sri Lankan social formation.

by Rajan Philips

Sri Lanka didn’t need a Y2K (year 2000) problem at the dawn of the 21st century, indeed, the third millennium. The island of millenniums had enough baggage from the old century to carry over into the new century, or from the old millennium to the new. Old problems were carried with new mutations and whole new other ones were added. The war that was muddled through the nineties consumed almost the entire first decade of the new century, before ending in 2009. The end of the war did end much of the social tragedy that it created, but it did not end the farcical continuation of war by political means. Mercifully, the killings ended but the agony of the living has persisted with no certainty about the dead and the missing. Not to mention the endless spat over how many died, with nary a thought or hand for the survivors of war and their livelihood struggles.

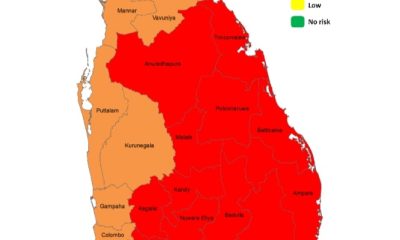

The war added new mutations to the old national question. The emergence of the Tamil diaspora and with it the phenomenon of diasporic nationalism, are developments that no one could have foreseen even as late as 1982. Equally, at both the state and societal levels, Sri Lanka has not fully come to terms with the rise of new strands of Sinhala Buddhist nationalism outside the ambits of mainstream political parties among the Sinhalese. Add to these, the coming of age of Muslim nationalism after having long been in the shadows of Sinhala and Tamil politics. These developments have defined the 21st century course of Sri Lanka’s never ending constitutional odyssey, especially involving the fate or the future of the Thirteenth Amendment, the Provincial Councils, and even the Executive Presidency.

A new dimension to the course of politics was provided by the end of the war itself, rather by the debate over how the war ended and whether or not war crimes were committed. Twelve years after the war ended, there are no answers in sight to any of these questions. There are no permanently correct answers in politics, but the task of every generation is to keep the balance on the side of more correct than incorrect answers. As things are in 2021, and thanks to an untoward juncture of a global pandemic and government incompetence, there are mostly only incorrect answers and hardly any correct answers to the many questions that Sri Lankans are facing. The current juncture will pass one way or another, but the questions that have been raised in the aftermath of the war are not likely to be answered satisfactorily any time soon.

A Dysfunctional Family

If Sri Lanka is a family of nationalisms, it has been for the most part a dysfunctional one. This is because Sri Lanka’s nationalisms have grown into being more conflictual and competitive than being complementary. The war and its aftermaths would appear to have exacerbated these tendencies and the unfolding of diasporic and Jathika Chinthanya phenomena would certainly attest to this. At the same time, their emergence also provide insights into the social and cultural roots of the nationalist stirrings among the Sinhalese, Tamils and the Muslims. Identifying and sharing these insights is needed to get rid of the always simplistic, and very often offensive, stereotypes which for far too long informed each community’s understanding of the other.

As stereotypes go, “Mahavamsa mindset” apparently sums up the Tamil understanding of Sinhala nationalism. For the Sinhalese, Tamil nationalistic claims are nothing more than a new ruse for Vellala domination. And Sri Lankan Muslim nationalism is simply rejected as Sri Lankan manifestation of global Islamic fundamentalism. There is more to each nationalism than these stereotypes, and each involves the lives and mores of people that cannot be summarily dismissed in any approach to accommodating them and making them complementary to one another. There are people in each community who do not subscribe to the narrow nationalistic claims that are made on behalf of their community. And stereotyping smudges them as well out of recognition.

As stereotypes go, “Mahavamsa mindset” apparently sums up the Tamil understanding of Sinhala nationalism. For the Sinhalese, Tamil nationalistic claims are nothing more than a new ruse for Vellala domination. And Sri Lankan Muslim nationalism is simply rejected as Sri Lankan manifestation of global Islamic fundamentalism. There is more to each nationalism than these stereotypes, and each involves the lives and mores of people that cannot be summarily dismissed in any approach to accommodating them and making them complementary to one another. There are people in each community who do not subscribe to the narrow nationalistic claims that are made on behalf of their community. And stereotyping smudges them as well out of recognition.

It might not be widely known outside the JC universe that the political roots of the two intellectual prime movers (Dr. Gunadasa Amarasekara and Prof. Nalin de Silva) behind JC are traceable more to Marxism and left politics than to any Mahavamsa mindset. In fact, one of them (Prof. de Silva) is known to have been a defender of the right of self-determination of the Tamil people before 1983. The open economy politics that began in 1977 and its social eruption in 1983 have more to do with the emergence of the Tamil diaspora and the Jathika Chinthanya soul searching among the Sinhalese intelligentsia, than anything that stereotypical explanations can provide.

The violence of 1983 impacted the Tamils indiscriminately and directly led to the emergence of the Tamil diaspora. On the other hand, the backlash to 1983 from outside Sri Lanka, especially the West and human rights organizations, may have been a factor in the energization of the JC school after 1983. The UNP government of the day wholly owned the 1983 disaster and deserved a great deal more than whatever blame it got and wherever it came from. JC was opposed to the UNP government’s open economy swindle and its cultural sellout, and it resented the government’s cunning approach to the Tamil national question. That was to parley with Tamil politicians in secret, and organize violence against Tamil civilians in the open. When 1983 went out of control, the backlash was not only against the government, but besmirched the entire Sinhalese society, including those who were revolted by the violence and others who were intractably opposed to the government. And there were backlash echoes from different fragments in the Sri Lankan social formation.

The fragmentation of the social formation and the creation of multiple political spaces was another outcome of the open economy and the political makeover under the UNP government. Thus, there was a new sociopolitical space for the off springs of the old, westernized Ceylonese middle class. It is not unfair to characterize the NGOs as being among the occupants of this space. And the children of 1956 were not neglected, at least from the economic standpoint. The more mobile among them easily filled up the economic spaces that the open economy created.

And for their social reproduction outside the vernacular, with a western accent, President Jayewardene gave them international schools. If that was JRJ’s belated rejoinder to the schools’ takeover of the 1960s, and it certainly was, he was not particularly looking to provide reparation to the Churches who lost their schools then. Worse, JRJ snobbishly abandoned the entire national school system, which he had the absolute power to retool anyway he wanted – to provide international education with a national accent to the children of 1977.

There was another aspect to the open economy that the UNP, and every government thereafter, neither recognized nor addressed. It was the orphaning of the state sector at the altar of the open economy. The salaries and compensation levels in the state sector were instantly and massively devalued by the opening of the economy and the aligning of market prices and private sector remunerations to global rates. I do not think this anomaly has been satisfactorily addressed to date. If Singapore is the vaunted model, you cannot have a competitive public sector without matching compensation with the private sector. It is no secret that some of the best and the brightest in a whole generation opted not to join the Central Bank, the universities or government institutions.

Political Limitations

The upshot of these changes was the emergence of two contending formations. One of the two, the NGO-formation (to call it loosely with no disparagement intended), wanted to use 1983 as a platform to recast Sri Lanka’s political society fundamentally different from what had led to the catastrophe of 1983. The new society would be plural and secular, would celebrate its diversity and welcome devolution. Intellectually, ethno-nationalism would be called out for what it is not – not an essential human condition.

The other, the JC-formation (so called, for convenience), has diametrically been opposed to any and all of the above. The JC thinking is also indicative of the unique exceptionalism that Sinhala Buddhist nationalism is uniquely constrained to project unlike Tamil nationalism or Muslim nationalism, both of which have external cultural validations to fall back on by virtue of language (in South India) and religion (Islam), respectively. The JC response in effect might be seen as a response to a sense of besiegement of the Sinhalese by forces from within (NGOs) and without (the West).

At the political level, the NGO formation found its spearheads alternatingly in Chandrika Kumaratunga and Ranil Wickremesinghe. Their accomplishments fell far below expectations. The JC formation waited patiently for the most authentic Sinhala Buddhist leader in Mahinda Rajapaksa, and had its golden decade from 2005 to 2015. The rest of the Sri Lankan political field, both individuals and organizations and of all ethnic groups, have been scurrying between the two main political polarities at regular intervals. The JVP and the JHU, both beneficiaries of JC affiliations at some point, have been in both political alliances and have also splintered over which side they should be permanently aligned with. The Tamil and the Muslim political parties have had their cracks of affiliations with the two main alliances and have little to show as results for their efforts.

Mahinda Rajapaksa had his setback when the people rejected his attempt to extend his presidency to a third term. Gotabaya Rajapaksa was elected promising vistas of prosperity and splendour. But the country is living through a rather dismal record of incompetence quite different from what was handsomely promised. The ‘young’ SLPP that was seen by some as a permanent incubator of future presidents. Instead, the limitations of the executive presidency have been exposed like never before. The JVP is now making a mark as a sharp opposition party in parliament. JHU’s Champika Ranawaka, perhaps the only politician with credible presidential ambition but without a political vehicle of his own, is now a member of convenience in Sajith Premadasa’s Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB).

Fifty years ago, the JVP launched its first abortive insurrection ostensibly to liberate the rural poor through the agency of its youth. Within twenty years, the JVP staged its second coming and the Tamil militants launched their violent struggle. They have all run their course which came to an end in 2009. Political violence used to be justified as the last resort after all other avenues have been exhausted. The violent struggles in Sri Lanka from 1971 to the Easter bombings in 2019 were not launched after all other avenues were exhausted. The question to ask fifty years after 1971 is – what happens after the ultimatums of political violence have all been tried and exhausted as well? Should politics be reduced to a farce as the continuation of war by other means?

Features

Zelensky tells BBC Putin has started World War 3 and must be stopped

Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky continues to send out a firm message of defiance.

When we met this weekend in the government headquarters in Kyiv, he said that far from losing, Ukraine would end the war victorious. He was firmly against paying the price for a ceasefire deal demanded by President Vladimir Putin, which is withdrawing from strategic ground that Russia has failed to capture despite sacrificing tens of thousands of soldiers.

Putin, Zelensky said, has already started World War Three, and the only answer was intense military and economic pressure to force him to step back.

“I believe that Putin has already started it. The question is how much territory he will be able to seize and how to stop him… Russia wants to impose on the world a different way of life and change the lives people have chosen for themselves.”

What about Russia’s demand for Ukraine to hand over the 20% of the eastern region of Donetsk that it still holds – a line of towns Ukraine calls “fortress cities” – as well as more land in the southern regions of Kherson and Zaporizhzhia? Isn’t that, I asked, a reasonable request if it produces a ceasefire?

“I see this differently. I don’t look at it simply as land. I see it as abandonment – weakening our positions, abandoning hundreds of thousands of our people who live there. That is how I see it. And I am sure that this ‘withdrawal’ would divide our society.”

But isn’t it a good price to pay if that satisfies President Putin? Do you think it would satisfy him?

“It would probably satisfy him for a while… he needs a pause… but once he recovers, our European partners say it could take three to five years. In my opinion, he could recover in no more than a couple of years. Where would he go next? We do not know, but that he would want to continue the war is a fact.”

I met Volodymyr Zelensky in a conference room inside the heavily-guarded government enclave in a well-to-do corner of central Kyiv. In the interview he spoke mostly in Ukrainian.

You get a sense of the weight of leadership carried by Zelensky from the diligence of his security guards.

Visiting any head of state requires rigorous checks. But entering the presidential buildings in Kyiv takes the process to a level I have rarely experienced before.

It is not surprising in a country at war, with a president who has already been targeted by Russia.

Despite all that, the man who started as an entertainer, who won the Ukrainian version of Strictly Come Dancing in 2006, and played the role of an unexpected president of Ukraine in a TV comedy, before becoming the real-life president of Ukraine, seems to be remarkably resilient.

US President Donald Trump said on the eve of the most recent ceasefire talks in Geneva that “Ukraine better come to the table fast”.

He continues to default to putting more pressure on Ukraine than on Russia.

Western diplomats have indicated since last summer that Trump agrees with Putin that territorial concessions from Ukraine to Russia are the key to the ceasefire Trump wants, ideally before this coming summer.

Plenty of analysts outside the White House also judge that Ukraine cannot win the war and, without making concessions to Moscow, will lose it.

I asked Zelensky whether Trump and the others had a point.

“Where are you now?” Zelensky asked in return. “Today you are in Kyiv, you are in the capital of our homeland, you are in Ukraine. I am very grateful for this. Will we lose? Of course not, because we are fighting for Ukraine’s independence.”

Zelensky has often said that Ukraine can win, but what would victory look like?

Of course, he said, victory meant restoring normal lives for Ukrainians and ending the killing. But the wider view of victory he presented was all about a global threat that he says comes from Putin.

“I believe that stopping Putin today and preventing him from occupying Ukraine is a victory for the whole world. Because Putin will not stop at Ukraine.”

You are not saying that victory is getting all the land back, are you?

“We’ll do it. That is absolutely clear. It is only a matter of time. To do it today would mean losing a huge number of people – millions of people – because the [Russian] army is large, and we understand the cost of such steps. You would not have enough people, you would be losing them. And what is land without people? Honestly, nothing.”

“And we also don’t have enough weapons. That depends not just on us, but on our partners. So as of now that’s not possible but returning to the just borders of 1991 [the year Ukraine declared its independence, precipitating the final collapse of the Soviet Union] without a doubt, is not only a victory, it’s justice. Ukraine’s victory is the preservation of our independence, and a victory of justice for the whole world is the return of all our lands.”

A year ago, Zelensky visited the White House and received a reception one senior Western diplomat described to me as a pre-planned public “diplomatic mugging” from Donald Trump and his Vice-President, JD Vance.

Their argument, in the presence of the world’s media, was watched by millions around the world.

Trump, just inaugurated as president for the second time, was sending the strongest possible signal that the era of support Zelensky and Ukraine had relied on from President Joe Biden was over. Nato members were already on notice from the new administration. Vance had just got back from shattering Western European illusions about the strength of the trans-Atlantic alliance.

Since then, reportedly coached by Britain’s National Security Adviser Jonathan Powell among others, Zelensky has avoided public confrontations with Trump.

The US president has stopped almost all shipments of military aid to Ukraine. But the US still provides vital intelligence, and European countries are spending billions buying weapons from the Americans to give to Ukraine.

I asked Ukraine’s president about Trump’s often contradictory statements, recalling that among the untruths he has uttered is the accusation that Zelensky is a dictator who started the war – a precise echo of claims made by Vladimir Putin.

Zelensky laughed.

“I am not a dictator, and I didn’t start the war, that’s it.”

But can you trust President Trump? If you extract a security guarantee from him, I asked, would he keep his word? He is after all a man who changes his mind.

“It is not only President Trump, we’re talking about America. We are all presidents for the appropriate terms. We want guarantees for 30 years for example. Political elites will change, leaders will change.”

He meant that US security guarantees needed approval from Congress in Washington DC to make them watertight.

“They will be voted on in Congress for a reason. It’s not just presidents. Congress is needed. Because the presidents change, but institutions stay.”

In other words, Donald Trump might be unreliable, but he will not be there for ever.

Zelensky says those security guarantees would have to be in place before he could consider another American demand – the US demand for Ukraine to hold a general election by the summer, echoing another Russian talking point that Zelensky is an illegitimate president. Trump has not demanded elections in Russia, where Putin became leader for the first time on the last day of the 20th Century.

Zelensky said he had not decided whether to stand again, whenever an election is held: “I might run and might not.”

Elections were due in 2024, but they could not be held under martial law that was introduced after Russia’s full-scale invasion.

Holding postponed elections, Zelensky said, was technically possible if they had time to change the law to allow them to happen. But he needed security guarantees for Ukraine first.

He went on to raise so many potential problems about holding an election with millions of Ukrainians abroad as refugees and significant tracts of the country occupied by Russia that I suggested that in reality he was against the idea.

“If this is a condition for ending the war, let’s do it. I said, ‘honestly, you constantly raise the issue of elections’. I told the partners, ‘you need to decide one thing: you want to get rid of me or you want to hold elections? If you want to hold elections, (even if you are not ready to tell me honestly even now), then hold these elections honestly. Hold them in a way that the Ukrainian people will recognise, first of all. And you yourself must recognise that these are legitimate elections'”.

Volodymyr Zelensky has opponents and harsh critics here in Ukraine.

His government was rocked last autumn by a corruption scandal that led to the departure of his closest adviser.

But Zelensky, with a new team, still commands approval ratings that most leaders in Western Europe can only dream about.

He has irritated his allies at times with constant demands for more and better equipment. One of the accusations directed at him in the Oval Office by Trump and Vance a year ago was that he was not sufficiently grateful.

The latest item on his list is permission to manufacture American weapons under licence, including Patriot air defence missiles.

“Today the issue is air defence. This is the most difficult problem. Unfortunately, our partners still do not grant licenses for us to produce systems ourselves, for example, Patriot systems, or even missiles for the systems we already have. So far, we have not achieved success in this.”

Why won’t they do that?

“I don’t know. I have no answer.”

At the end of the interview, he switched from Ukrainian to English.

Given everything he had said, I asked him whether we needed to get ready for an even longer war in Ukraine.

“No, no, no, it’s two parallel tracks… you are playing chess with a lot of leaders, not with Russia. There is not one right way. You have to choose a lot of parallel steps, parallel directions. And one of these parallel ways will, I think, bring success. For us, success is to stop Putin.”

But Vladimir Putin isn’t going to end this war, is he? Unless he’s under massive pressure and he doesn’t seem to be.

“Yes and no. We will see. Yes and no. He doesn’t want, but doesn’t want doesn’t mean he will not. God bless. God bless, we will be successful. Thank you.”

And with that, he posed for photographs, shook hands with the BBC team, and strode out of the room.

[BBC]

Features

Reconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

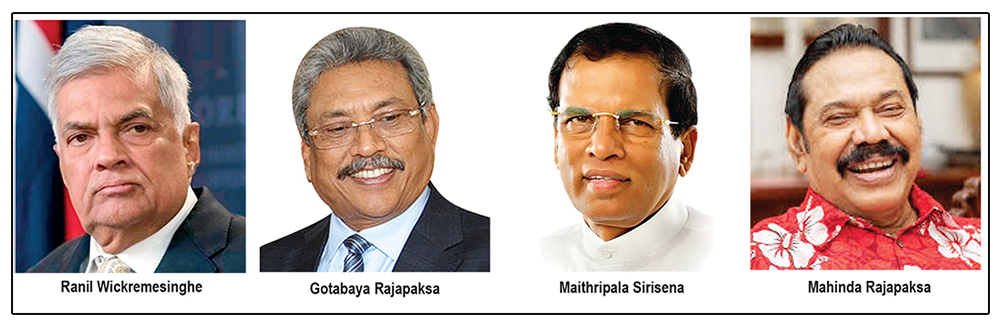

From the time the search for reconciliation began after the end of the war in 2009 and before the NPP’s victories at the presidential election and the parliamentary election in 2024, there have been four presidents and four governments who variously engaged with the task of reconciliation. From last to first, they were Ranil Wickremesinghe, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, Maithripala Sirisena and Mahinda Rajapaksa. They had nothing in common between them except they were all different from President Anura Kumara Dissanayake and his approach to reconciliation.

The four former presidents approached the problem in the top-down direction, whereas AKD is championing the building-up approach – starting from the grassroots and spreading the message and the marches more laterally across communities. Mahinda Rajapaksa had his ‘agents’ among the Tamils and other minorities. Gotabaya Rajapaksa was the dummy agent for busybodies among the Sinhalese. Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe operated through the so called accredited representatives of the Tamils, the Muslims and the Malaiayaka (Indian) Tamils. But their operations did nothing for the strengthening of institutions at the provincial and the local levels. No did they bother about reaching out to the people.

As I recounted last week, the first and the only Northern Provincial Council election was held during the Mahinda Rajapaksa presidency. That nothing worthwhile came out of that Council was not mainly the fault of Mahinda Rajapaksa. His successors, Maithripala Sirisena and Ranil Wickremesinghe as Prime Minister, with the TNA acceding as a partner of their government, cancelled not only the NPC but also all PC elections and indefinitely suspended the functioning of the country’s nine elected provincial councils. Now there are no elected councils, only colonial-style governors and their secretaries.

Hold PC Elections Now

And the PC election can, like so many other inherited rotten cans, is before the NPP government. Is the NPP government going to play footsie with these elections or call them and be done with it? That is the question. Here are the cons and pros as I see them.

By delaying or postponing the PC elections President AKD and the NPP government are setting themselves up to be justifiably seen as following the cynical playbook of the former interim President Ranil Wickremesinghe. What is the point, it will be asked, in subjecting Ranil Wickremesinghe to police harassment over travel expenses while following his playbook in postponing elections?

Come to think of it, no VVIP anywhere can now whine of unfair police arrest after what happened to the disgraced former prince Andrew Mountbatten Windsor in England on Thursday. Good for the land where habeas corpus and due process were born. The King did not know what was happening to his kid brother, and he was wise enough to pronounce that “the law must take its course.” There is no course for the law in Trump’s America where Epstein spun his webs around rich and famous men and helpless teenage girls. Only cover up. Thanks to his Supreme Court, Trump can claim covering up to be a core function of his presidency, and therefore absolutely immune from prosecution. That is by the way.

Back to Sri Lanka, meddling with elections timing and process was the method of operations of previous governments. The NPP is supposed to change from the old ways and project a new way towards a Clean Sri Lanka built on social and ethical pillars. How does postponing elections square with the project of Clean Sri Lanka? That is the question that the government must be asking itself. The decision to hold PC elections should not be influenced by whether India is not asking for it or if Canada is requesting it.

Apart from it is the right thing do, it is also politically the smart thing to do.

The pros are aplenty for holding PC elections as soon it is practically possible for the Election Commission to hold them. Parliament can and must act to fill any legal loophole. The NPP’s political mojo is in the hustle and bustle of campaigning rather than in the sedentary business of governing. An election campaign will motivate the government to re-energize itself and reconnect with the people to regain momentum for the remainder of its term.

While it will not be possible to repeat the landslide miracle of the 2024 parliamentary election, the government can certainly hope and strive to either maintain or improve on its performance in the local government elections. The government is in a better position to test its chances now, before reaching the halfway mark of its first term in office than where it might be once past that mark.

The NPP can and must draw electoral confidence from the latest (February 2026) results of the Mood of the Nation poll conducted by Verité Research. The government should rate its chances higher than what any and all of the opposition parties would do with theirs. The Mood of the Nation is very positive not only for the NPP government but also about the way the people are thinking about the state of the country and its economy. The government’s approval rating is impressively high at 65% – up from 62% in February 2025 and way up from the lowly 24% that people thought of the Ranil-Rajapaksa government in July 2024. People’s mood is also encouragingly positive about the State of the Economy (57%, up from 35% and 28%); Economic Outlook (64%, up from 55% and 30%); the level of Satisfaction with the direction of the country( 59%, up from 46% and 17%).

These are positively encouraging numbers. Anyone familiar with North America will know that the general level of satisfaction has been abysmally low since the Iraq war and the great economic recession. The sour mood that invariably led to the election of Trump. Now the mood is sourer because of Trump and people in ever increasing numbers are looking for the light at the end of the Trump tunnel. As for Sri Lanka, the country has just come out of the 20-year long Rajapaksa-Ranil tunnel. The NPP represents the post Rajapaksa-Ranil era, and the people seem to be feeling damn good about it.

Of course, the pundits have pooh-poohed the opinion poll results. What else would you expect? You can imagine which twisted way the editorial keypads would have been pounded if the government’s approval rating had come under 50%, even 49.5%. There may have even been calls for the government to step down and get out. But the government has its approval rating at 65% – a level any government anywhere in the Trump-twisted world would be happy to exchange without tariffs. The political mood of the people is not unpalpable. Skeptical pundits and elites will have to only ask their drivers, gardeners and their retinue of domestics as to what they think of AKD, Sajith or Namal. Or they can ride a bus or take the train and check out the mood of fellow passengers. They will find Verité’s numbers are not at all far-fetched.

Confab Threats

The government’s plausible popularity and the opposition’s obvious weaknesses should be good enough reason for the government to have the PC elections sooner than later. A new election campaign will also provide the opportunity not only for the government but also for the opposition parties to push back on the looming threat of bad old communalism making a comeback. As reported last week, a “massive Sangha confab” is to be held at 2:00 PM on Friday, February 20th, at the All Ceylon Buddhist Congress Headquarters in Colombo, purportedly “to address alleged injustices among monks.”

According to a warning quote attributed to one of the organizers, Dambara Amila Thero, “never in the history of Sri Lanka has there been a government—elected by our own votes and the votes of the people—that has targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana as this one.” That is quite a mouthful and worthier practitioners of Buddhism have already criticized this unconvincing claim and its being the premise for a gathering of spuriously disaffected monks. It is not difficult to see the political impetus behind this confab.

The impetus obviously comes from washed up politicians who have tried every slogan from – L-board-economists, to constitutional dictatorship, to save-our children from sex-education fear mongering – to attack the NPP government and its credibility. They have not been able to stick any of that mud on the government. So, the old bandicoots are now trying to bring back the even older bogey of communalism on the pretext that the NPP government has somewhere, somehow, “targeted and launched such systematic attacks against the entire Sasana …”

By using a new election campaign to take on this threat, the government can turn the campaign into a positively educational outreach. That would be consistent with the President’s and the government’s commitment to “rebuild Sri Lanka” on the strength of national unity without allowing “division, racism, or extremism” to undermine unity. A potential election campaign that takes on the confab of extremists will also provide a forum and an opportunity for the opposition parties to let their positions known. There will of course be supporters of the confab monks, but hopefully they will be underwhelming and not overwhelming.

For all their shortcomings, Sajith Premadasa and Namal Rajapaksa belong to the same younger generation as Anura Kumara Dissanayake and they are unlikely to follow the footsteps of their fathers and fan the flames of communalism and extremism all over again. Campaigning against extremism need not and should not take the form of disparaging and deriding those who might be harbouring extremist views. Instead, the fight against extremism should be inclusive and not exclusive, should be positively educational and appeal to the broadest cross-section of people. That is the only sustainable way to fight extremism and weaken its impacts.

Provincial Councils and Reconciliation

In the framework of grand hopes and simple steps of reconciliation, provincial councils fall somewhere in between. They are part of the grand structure of the constitution but they are also usable instruments for achieving simple and practical goals. Obviously, the Northern Provincial Council assumes special significance in undertaking tasks associated with reconciliation. It is the only jurisdiction in the country where the Sri Lankan Tamils are able to mind their own business through their own representatives. All within an indivisibly united island country.

But people in the north will not be able to do anything unless there is a provincial council election and a newly elected council is established. If the NPP were to win a majority of seats in the next Northern Provincial Council that would be a historic achievement and a validation of its approach to national reconciliation. On the other hand, if the NPP fails to win a majority in the north, it will have the opportunity to demonstrate that it has the maturity to positively collaborate from the centre with a different provincial government in the north.

The Eastern Province is now home to all three ethnic groups and almost in equal proportions. Managing the Eastern Province will an experiential microcosm for managing the rest of the country. The NPP will have the opportunity to prove its mettle here – either as a governing party or as a responsible opposition party. The Central Province and the Badulla District in the Uva Province are where Malaiyaka Tamils have been able to reconstitute their citizenship credentials and exercise their voting rights with some meaningful consequence. For decades, the Malaiyaka Tamils were without voting rights. Now they can vote but there is no Council to vote for in the only province and district they predominantly leave. Is that fair?

In all the other six provinces, with the exception of the Greater Colombo Area in the Western Province and pockets of Muslim concentrations in the South, the Sinhalese predominate, and national politics is seamless with provincial politics. The overlap often leads to questions about the duplication in the PC system. Political duplication between national and provincial party organizations is real but can be avoided. But what is more important to avoid is the functional duplication between the central government in Colombo and the provincial councils. The NPP governments needs to develop a different a toolbox for dealing with the six provincial councils.

Indeed, each province regardless of the ethnic composition, has its own unique characteristics. They have long been ignored and smothered by the central bureaucracy. The provincial council system provides the framework for fostering the unique local characteristics and synthesizing them for national development. There is another dimension that could be of special relevance to the purpose of reconciliation.

And that is in the fostering of institutional partnerships and people to-people contacts between those in the North and East and those in the other Provinces. Linkages could be between schools, and between people in specific activities – such as farming, fishing and factory work. Such connections could be materialized through periodical visits, sharing of occupational challenges and experiences, and sports tournaments and ‘educational modules’ between schools. These interactions could become two-way secular pilgrimages supplementing the age old religious pilgrimages.

Historically, as Benedict Anderson discovered, secular pilgrimages have been an important part of nation building in many societies across the world. Read nation building as reconciliation in Sri Lanka. The NPP government with its grassroots prowess is well positioned to facilitate impactful secular pilgrimages. But for all that, there must be provincial councils elections first.

by Rajan Philips

Features

Barking up the wrong tree

The idiom “Barking up the wrong tree” means pursuing a mistaken line of thought, accusing the wrong person, or looking for solutions in the wrong place. It refers to hounds barking at a tree that their prey has already escaped from. This aptly describes the current misplaced blame for young people’s declining interest in religion, especially Buddhism.

It is a global phenomenon that young people are increasingly disengaged from organized religion, but this shift does not equate to total abandonment, many Gen Z and Millennials opt for individual, non-institutional spirituality over traditional structures. However, the circumstances surrounding Buddhism in Sri Lanka is an oddity compared to what goes on with religions in other countries. For example, the interest in Buddha Dhamma in the Western countries is growing, especially among the educated young. The outpouring of emotions along the 3,700 Km Peace March done by 16 Buddhist monks in USA is only one example.

There are good reasons for Gen Z and Millennials in Sri Lanka to be disinterested in Buddhism, but it is not an easy task for Baby Boomer or Baby Bust generations, those born before 1980, to grasp these bitter truths that cast doubt on tradition. The two most important reasons are: a) Sri Lankan Buddhism has drifted away from what the Buddha taught, and b) The Gen Z and Millennials tend to be more informed and better rational thinkers compared to older generations.

This is truly a tragic situation: what the Buddha taught is an advanced view of reality that is supremely suited for rational analyses, but historical circumstances have deprived the younger generations over centuries from knowing that truth. Those who are concerned about the future of Buddhism must endeavor to understand how we got here and take measures to bridge that information gap instead of trying to find fault with others. Both laity and clergy are victims of historical circumstances; but they have the power to shape the future.

First, it pays to understand how what the Buddha taught, or Dhamma, transformed into 13 plus schools of Buddhism found today. Based on eternal truths he discovered, the Buddha initiated a profound ethical and intellectual movement that fundamentally challenged the established religious, intellectual, and social structures of sixth-century BCE India. His movement represented a shift away from ritualistic, dogmatic, and hierarchical systems (Brahmanism) toward an empirical, self-reliant path focused on ethics, compassion, and liberation from suffering. When Buddhism spread to other countries, it transformed into different forms by absorbing and adopting the beliefs, rituals, and customs indigenous to such land; Buddha did not teach different truths, he taught one truth.

Sri Lankan Buddhism is not any different. There was resistance to the Buddha’s movement from Brahmins during his lifetime, but it intensified after his passing, which was responsible in part for the disappearance of Buddhism from its birthplace. Brahminism existed in Sri Lanka before the arrival of Buddhism, and the transformation of Buddhism under Brahminic influences is undeniable and it continues to date.

This transformation was additionally enabled by the significant challenges encountered by Buddhism during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries (Wachissara 1961, Mirando 1985). It is sad and difficult to accept, but Buddhism nearly disappeared from the land that committed the Teaching into writing for the first time. During these tough times, with no senior monks to perform ‘upasampada,’ quasi monks who had not been admitted to the order – Ganninanses, maintained the temples. Lacking any understanding of the doctrinal aspects of Buddha’s teaching, they started performing various rituals that Buddha himself rejected (Rahula 1956, Marasinghe 1974, Gombrich 1988, 1997, Obeyesekere 2018).

The agrarian population had no way of knowing or understanding the teachings of the Buddha to realize the difference. They wanted an easy path to salvation, some power to help overcome an illness, protect crops from pests or elements; as a result, the rituals including praying and giving offerings to various deities and spirits, a Brahminic practice that Buddha rejected in no uncertain terms, became established as part of Buddhism.

This incorporation of Brahminic practices was further strengthened by the ascent of Nayakkar princes to the throne of Kandy (1739–1815) who came from the Madurai Nayak dynasty in South India. Even though they converted to Buddhism, they did not have any understanding of the Teaching; they were educated and groomed by Brahminic gurus who opposed Buddhism. However, they had no trouble promoting the beliefs and rituals that were of Brahminic origin and supporting the institution that performed them. By the time British took over, nobody had any doubts that the beliefs, myths, and rituals of the Sinhala people were genuine aspects of Buddha’s teaching. The result is that today, Sri Lankan Buddhists dare doubt the status quo.

The inclusion of Buddhist literary work as historical facts in public education during the late nineteenth century Buddhist revival did not help either. Officially compelling generations of students to believe poetic embellishments as facts gave the impression that Buddhism is a ritualistic practice based on beliefs.

This did not create any conflict in the minds of 19th agrarian society; to them, having any doubts about the tradition was an unthinkable, unforgiving act. However, modernization of society, increased access to information, and promotion of rational thinking changed things. Younger generations have begun to see the futility of current practices and distance themselves from the traditional institution. In fact, they may have never heard of it, but they are following Buddha’s advice to Kalamas, instinctively. They cannot be blamed, instead, their rational thinking must be appreciated and promoted. It is the way the Buddha’s teaching, the eternal truth, is taught and practiced that needs adjustment.

The truths that Buddha discovered are eternal, but they have been interpreted in different ways over two and a half millennia to suit the prevailing status of the society. In this age, when science is considered the standard, the truth must be viewed from that angle. There is nothing wrong or to be afraid of about it for what the Buddha taught is not only highly scientific, but it is also ahead of science in dealing with human mind. It is time to think out of the box, instead of regurgitating exegesis meant for a bygone era.

For example, the Buddhist model of human cognition presented in the formula of Five Aggregates (pancakkhanda) provides solutions to the puzzles that modern neuroscience and philosophers are grappling with. It must be recognized that this formula deals with the way in which human mind gathers and analyzes information, which is the foundation of AI revolution. If the Gen Z and Millennial were introduced to these empirical aspects of Dhamma, they would develop a genuine interest in it. They thrive in that environment. Furthermore, knowing Buddha’s teaching this way has other benefits; they would find solutions to many problems they face today.

Buddha’s teaching is a way to understand nature and the humans place in it. One who understands this can lead a happy and prosperous life. As the Dhammapada verse number 160 states – “One, indeed, is one’s own refuge. Who else could be one’s own refuge?” – such a person does not depend on praying or offering to idols or unknown higher powers for salvation, the Brahminic practice. Therefore, it is time that all involved, clergy and laity, look inwards, and have the crucial discussion on how to educate the next generation if they wish to avoid Sri Lankan Buddhism suffer the same fate it did in India.

by Geewananda Gunawardana, Ph.D.

-

Features23 hours ago

Features23 hours agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features23 hours ago

Features23 hours agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features23 hours ago

Features23 hours agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Features23 hours ago

Features23 hours agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction