Features

Richard de Zoysa: ‘A Life Brutally Taken Away 31 Years Ago.’

By Dr Laksiri Fernando

I was first planning to make just a comment to Roel Raymond’s article on Richard de Zoysa, her departed uncle (Colombo Telegraph, 14 March 2021). But after rereading the extremely sensible and topical article “Remembering Richard: And the Silence that Empowers Those in Pursuit of Power” . I finally decided to write this short tribute. I have used in the headline of this article a phrase in her column–– ‘a life brutally taken 31 years ago.’

In Raymond’s article, she has brought the despicable nature of power politics, in Sri Lanka and elsewhere, to the forefront. As she says, “in understanding the nature of power — I have argued with those who will listen — I understand that small men and women will be continually crushed by the men and women who are single-minded in pursuit of power.” This is exactly what happened to Richard who expressed his views frankly and openly, without any intention of power.

His Last Article

I have not known Richard, personally. I came to know his mother, Dr. Manorani Saravanamuttu, and her plight, when she came to Geneva seeking justice (not revenge) before the UN Commission on Human Rights in 1990. However, I knew of Richard as an impressive actor and a convincing writer. He expressed his views frankly and openly. Let me shortly speak about his last article, published on 11 February 1990, a week before his killing, in The Sunday Island. It was titled “A Manifesto for an Alternative Society.” There was nothing subversive in this article, except his alternative vision.

The reason to write this article appears to be Gunadasa Amarasekara’s previous article on Jathika Chinthanaya (National Ideology), an ideology which had been in circulation for some time then. Although he appears to be soft on Amarasekara personally, perhaps as a prominent literary figure, Richard has questioned and countered many of the arguments of Amarasekara.

It was Amarasekara’s argument that communism, or socialism, was crumbling in Eastern Europe because of the force of ‘national ideology.’ In contrast, Richard was arguing that it was crumbling because socialism was imposed in Eastern Europe ‘from above and beyond their borders.’ At the same time, Richard was contending that Jathika Chinthanaya was trying to do the same to minority communities, Tamils and Muslims, within the Sri Lankan national borders.

In talking about ‘indigenous intellectuals,’ Amarasekara has listed only Sinhala intellectuals, from Anagarika Dharmapala to Martin Wickremasinghe. In contrast, Richard was saying, “This seems to suggest that there were either no Tamil or Muslim intellectuals or that the Tamils and Muslims are not indigenous to this island.” His tone was not angry but sarcastic.

Nothing Subversive

There was no indication, in this article, that Richard was supporting the JVP or its violence. Only sympathetic comment was in respect of JVPs alleged ‘distancing from Amarasekara’s or communalist ideology.’ There are only three sentences where ‘JVP’ appears. The rest of the article was generally theoretical. It is possible that those who ordered Richard’s abduction did not at all understand what he was saying. It is true that Richard was believing in Marxism-Leninism, right or wrong. The following is the way he summarised his ‘Manifesto for an Alternative Society.’

“The answer is surely a secular state, truly secular, with icons except the institutions of the state itself, and guided by the principles of sound management within an ideological framework which does not carry within itself the seeds of either extremism of Jathika Chinthanaya or the potential anarchy of cultural pluralism.”

I suggest that Marxism-Leninism, in its original form, does provide the theoretical basis, which must be flexible enough to accommodate the strains arising along the way. It is not cynical to declare that politics is the art of the possible, as long as one does not equate ‘possible’ with anything goes.”

Context of Gross Violations

I was about to make a statement on the ‘patterns of gross human rights violations’ before the UN Commission on Human Rights in Geneva on behalf of the World University Service (WUS), when Chakravarthi Raghavan of the Inter Press Service (IPS) came to me and handed over a telegram that he had received from their headquarters in Lisbon. It was 19 February (Monday) around 11.30am. IPS communications were so quick.

I read the telegram, as a part of my statement, and asked for a clarification from the Sri Lankan representative. It was shocking in the Commission room because of the quickness (and perhaps my loud voice!). It was Sunil de Silva, then Attorney General, who was at the Commission as the key representative of Sri Lanka. He immediately left the chamber, and in the afternoon made a statement that the government would be inquiring in to the incident. It never happened thereafter. Sunil himself had to leave the country in 1992.

Richard de Zoysa’s killing was not an isolated incident during that time. Even before and after, there had been an evolving pattern of gross violations by the Ranasinghe Premadasa government, the JVP and the LTTE, to name only the main perpetrators. Let me quote the first two paragraphs of the Country Report of the Human Rights Watch for the year 1990 to summarise the situation.

“Violence against civilians by all parties to the conflict continued to characterize the war in Sri Lanka in 1990. In the south, the murder in February of a prominent journalist brought world attention to the activity of government-backed death squads, which then seemed to subside. An armed Sinhalese nationalist group, the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), which was responsible for several thousand killings, appeared to be crushed when its top leaders were apparently killed in custody in late 1989. By late 1990, however, both the JVP and the death squads had resurfaced. In the northeast, human rights conditions reached a new low in June, after the breakdown of a 14-month ceasefire between the Sri Lankan government and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), the largest Tamil opposition group.

“Even for Sri Lanka, the utter brutality on all sides that followed the LTTE’s June attacks on police stations and military installations in the northeast was unprecedented, creating an atmosphere of terror. The LTTE and the Sri Lankan security forces both carried out massacres of civilians. The Army summarily executed suspected Tamil insurgents; the LTTE did the same to Sri Lankan police officers. Both the LTTE and the security forces used civilians as shields against attacks. The Army engaged in heavy bombing in civilian areas, resulting in damage to homes, hospitals, temples, churches, and pedestrians. Burning bodies appeared along roadsides in many parts of the country, and reports of mass arrests and disappearances increased.”

Conclusion

As Roel Raymond has emphasised in her article on Richard de Zoysa (her deceased uncle), power politics is the main reason for the violent situations then and today, in Sri Lanka and almost everywhere. There is a need for a new generation of people who think, speak and act differently, considering politics not as a means for power, but as an avenue for Dhamma (virtue) and peace. This may be unimaginable for some, today. But it should come sooner than later. The power-based politics, not only in the government but also in the Opposition, should be discouraged and disapproved. That is the only way to preserve souls like Richard de Zoysa.

Features

A 20-year reflection on housing struggles of Tsunami survivors

Revisiting field research in Ampara

by Prof. Amarasiri de Silva

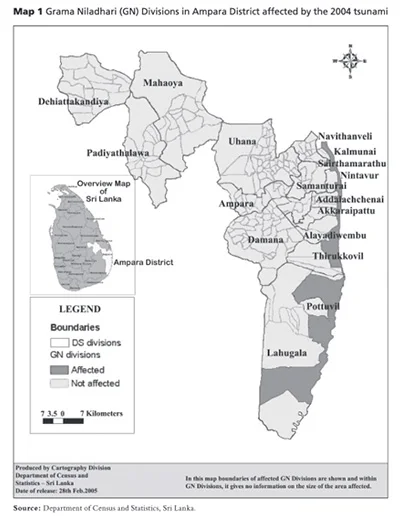

The 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, also known as the Boxing Day tsunami, triggered by a magnitude 9.1 earthquake off the coast of Sumatra on 26 Dec., 2004, had a catastrophic impact on Sri Lanka. It is estimated to have released energy equivalent to 23,000 Hiroshima-type atomic bombs, wiping out hundreds of communities in minutes. The tsunami struck Sri Lanka’s eastern and southern coasts approximately two hours after the earthquake. The eastern shores, facing the earthquake’s epicenter, bore the brunt of the waves, affecting settlements on the east coast. The tsunami displaced many families and devastated villages and communities in the affected districts of Sri Lanka. Although Boxing Day is associated with exchanging gifts after Christmas and was a time to give to the less fortunate, it brought havoc in Sri Lanka to many communities. It resulted in approximately 31,229 deaths and 4,093 people missing. In terms of the dead and missing numbers, Sri Lanka’s toll was second only to Indonesia (126,804, missing 93,458, displaced 474,619). Twenty-five beach hotels were severely damaged, and another 6 were completely washed away. More than 240 schools were destroyed or sustained severe damage. Several hospitals, telecommunication networks, coastal railway networks, etc., were also damaged. In addition, one and a half million people were displaced from their homes.

Ampara district was a hard-hit district, where more than 10,000 people died. A Galle bound train from Colombo, carrying about 1,700 passengers visiting their ancestral homes and villages, on the Sunday after the Christmas holidays, was struck by the tsunami near Telwatta; most of them were killed.

About 8,000 people were killed in the northeast region, which the LTTE controlled at the time. The Ampara district was a hard-hit district, with more than 10,000 people dying and many more displaced. In sympathy with the victims, the Saudi Arabian government established a grant to construct houses to assist 500 displaced families in Ampara in 2009. The Saudi Envoy in Colombo presented the house keys to President Mahinda Rajapaksa in 2011 for distribution to tsunami victims in the Ampara district. However, due to the protests by local majoritarian ethnic groups, the government intervened, and a court ruling halted the housing distribution to the victims, mandating that houses be allocated according to the country’s population ratio. The project includes residential units and amenities such as a school, a supermarket complex, a hospital, and a mosque, making it unique for Muslim people. Saudi government ambassador Khalid Hamoud Alkahtani engaged in discussions with the Sri Lankan government to sort out the issues and agreed to give the houses to the respective victims.

Immediate Recovery

The immediate relief work was initiated just after the disaster, and the government had financial and moral support from local people and countries worldwide. As most displaced people were children and women, restoring at least basic education facilities for affected children was a high priority. By mid-year, 85 percent of the children in tsunami-affected areas were back in school, which showed that the relief programme in school education was a success.

Relief efforts for households included the provision of finances to meet immediate needs. Compensation of Rs.15,000 (US$150) was offered for victims towards funeral expenses; livelihood support schemes included Payment of Rs.375 (US$3.75) in cash and rations for each member of a family unit per week, a payment of Rs. 2,500 (US$25) towards kitchen utensils per family. These initial measures were largely successful, though there were some problems with a lack of coordination, as witnessed. (See Map 1)

The most considerable financing needs were in the housing sector. The destruction of private assets was substantial (US$700 million), in addition to public infrastructure and other assets. Loss of current output in the fisheries and tourism sectors—which were severely affected—was estimated at US$200 million and US$130 million, respectively.

2004 tsunami-impacted zone. (Image courtesy Reliefweb)

Strands of Hope: Progress Made for Tsunami-Affected Communities of Sri Lanka

By mid-June 2005, the number of displaced people was down to 516,000 from approximately 800,000 immediately after the tsunami, as people went home—even if the homes in question were destroyed or damaged—and were taken off the books then. At first, an estimated 169,000 people living in schools and tents were mainly transferred to transitional shelters/camps—designed to serve as a stopgap between emergency housing and permanent homes. This transitional shelter was only supplied to affected households in the buffer zone.

By late August 2005, The Task Force for Rebuilding the Nation (TAFREN) estimated that 52,383 transitional shelters, accommodating an estimated 250,000 tsunami-affected people, had been completed since February 2005 at 492 sites. Those transitional housing programme shelters were expected to be completed with 55,000 by the end of September 2005. This goal seems more than achievable. I did not find evidence to show that it has been achieved.

I did my field research in Ampara district with support from UNDP Colombo, the Department for Research Cooperation, and the Swedish International Development Cooperation.

My research shows that the tsunami affected families in Muslim settlements along the East Coast had a severe housing problem for two reasons.

• First, the GoSL has declared that land within 65 meters of the sea is unsafe for living due to possible seismic effects, and people are thus prohibited from engaging in any construction in that beach area. This land strip is the traditional living area of the Muslims, particularly the fisher folk. Families living along the narrow beach strip have not been offered alternative land or adequate compensation to buy land outside the 65-metre zone.

• Second, the LTTE has prohibited Muslims from building houses on land purchased for them by outside agencies on the pretext that it belongs to the Tamils.

The GoSL established several institutions as a response strategy for post-tsunami recovery after the failure of P-TOMS. The Task Force for Rebuilding the Nation (TAFREN), the Task Force for Relief (TAFOR), and the Tsunami Housing Reconstruction Unit (THRU) were the lead agencies created through processes involving private and public sector participation. In November 2005, following the election of President Mahinda Rajapaksa, the Reconstruction and Development Agency (RADA)was set up. This became an authority with executive powers following the parliamentary ratification of the RADA Act in 2006. RADA’s mandate was to accelerate reconstruction and development activities in the affected areas, functionally replacing all the tsunami organizations and a significant part of the former RRR Ministry. According to RADA, the total number of houses built so far (as of May 2006) in Ampara is 629, while the total housing units pledged is 6,169. At the time of the research (March to June 2006), no housing projects were completed in a predominantly Muslim area.

Compensation for damaged houses was not based on a consistent scheme. As a result, some families received large sums, while others did not get any money. In some instances, those who collected compensation were not the affected families. The Auditor General, S.C. Mayadunne, noted that Payment of an excessive amount, even for minor damages, is due to the payments being made without assessing the cost of restoring the houses to normal condition. (For example, Rs. 100,000 had been paid for minor damages of Rs. 10,000) … Payments made without identifying the value of the damaged houses, thus resulting in heavy expenditure by the government (For example, a sum of Rs. 250,000 had been paid for the destruction of a temporary house valued at Rs. 10,000) (Mayadunne, 2005, p. 8). That compensation was not paid according to an acceptable scheme, which led to agitation among the affected people and provided an opportunity for political manipulation. The LTTE and the TRO requested direct aid for reconstruction work in LTTE-controlled areas. The poor response of the GoSL to this demand was interpreted as indifference on its part towards ethnic minorities in Ampara. Meanwhile, the GoSL provided direct support for tsunami-affected communities in southern Sri Lanka, where the majority were Sinhalese, strengthening this allegation.

Land scarcity in tsunami-affected Ampara and disputes over landownership in the area were the main reasons for not completing the housing programmes. The LTTE contended that the land identified for building houses by the GoSL or purchased by civil society organisations for constructing such houses belongs to the Tamils, an ideology based on a myth of their own, a Tamil hereditary Homeland—paarampariyamaana taayakam’ (Peebles, 1990, p. 41). Consequently, housing programmes could not be implemented at that time.

The land question in the Eastern Province has a history that dates back to 1951 when the Gal Oya Colonisation scheme was established. According to the minority version of this history, in a report submitted by Dr. Hasbullah and his colleagues, it shows that the colonists were selected overwhelmingly from among the Sinhalese rather than the Muslims and Tamils, who were a majority in Ampara at that time, and, as a result, the ethnic balance of Ampara District was disrupted. However, conversely, B.H. Farmer reported in 1957 that Tamils, especially Jaffna Tamils, were ‘chary’ and did not have a ‘tradition of migration,’ which was the apparent reason for less Tamil representation among the colonists of Gal Oya. According to Farmer, up to December 31, 1953, between five and 16 percent of the colonists were chosen from the Districts of Batticaloa, Jaffna and Trincomalee, predominantly Tamil. Contradictory evidence (with a political coloring following the recent rise of ethnicity in this discourse) reports by Dr. Hasbullah that 100,000 acres of agricultural land in the East have been ‘illegally transferred from Muslims to the Tamils’ since the 1990s. The Tamils, however, believe that the land in the Eastern Province is part and parcel of the Tamil Homeland. This new political ideology of landownership that emerged at that time in the ethnopolitical context of the Eastern Province has intensified land (re)claiming in Ampara by Muslims and Tamils.

According to Tamil discourse, the increase in the value of land in Ampara over the past two decades has led to rich Muslims purchasing land belonging to poor Tamils, resulting in ethnic homogenization in the coastal areas of the District in favor of the Muslims. ‘Violence against Tamils was also used in some areas to push out the numerically small Tamil service caste communities’ as Hasbullah says. In a situation with an ideological history of land disputes, finding new land for the construction of houses for Muslim communities affected by the tsunami posed a challenge at that time.

In the face of this challenge, Muslims in Ampara sought assistance from Muslim politicians and organisations that willingly came forward to assist them. The efforts made by these politicians and civil society organisations to erect houses for tsunami-affected Muslim families were forcibly curtailed by the LTTE. Consequently, a proposed housing program for Muslims in Kinnayady Kiramam in Kaththankudi was abandoned in 2005. Development of the four acres of land bought by the Memon Sangam in Colombo for tsunami victims of Makbooliya in Marathamunai was prohibited in 2005. Similar occurrences have been reported in Marathamunai Medduvedday. Mrs. Ferial Ashraff, at that time Minister of Housing and Common Amenities, wanted to build houses in Marathamunai, Periyaneelavanai DS division (Addaippallam), the Pandirippu Muslim area, and in Oluvil–Palamunai, but the LTTE proscribed all such initiatives.

In the face of this challenge, Muslims in Ampara sought assistance from Muslim politicians and organisations that willingly came forward to assist them. The efforts made by these politicians and civil society organisations to erect houses for tsunami-affected Muslim families were forcibly curtailed by the LTTE. Consequently, a proposed housing program for Muslims in Kinnayady Kiramam in Kaththankudi was abandoned in 2005. Development of the four acres of land bought by the Memon Sangam in Colombo for tsunami victims of Makbooliya in Marathamunai was prohibited in 2005. Similar occurrences have been reported in Marathamunai Medduvedday. Mrs. Ferial Ashraff, at that time Minister of Housing and Common Amenities, wanted to build houses in Marathamunai, Periyaneelavanai DS division (Addaippallam), the Pandirippu Muslim area, and in Oluvil–Palamunai, but the LTTE proscribed all such initiatives.

The Islamabad housing scheme in Kalmunai Muslim DS division and the construction of houses by Muslim individuals in Karaithivu were banned, and threats were issued by the LTTE and a Tamil military organisation called Ellai Padai (Boundary Forces). Because the GoSL and the intervening agencies could not resolve the housing problem, the affected communities became disillusioned and lost confidence in the GoSL departments, aid agencies, and international NGOs. Much effort and resources were wasted in finding land and designing housing programmes that have not materialised. Some funds pledged by external agencies failed to materialise, causing harm to low-income families. Efforts to provide housing for tsunami-affected people in the Ampara District at that time highlighted their vulnerability to LTTE threats and the power politics of participating agencies. Regarding housing and land issues, the Muslim people of Ampara adopted two approaches to address their challenges. First, in some cases, they reached a compromise with the LTTE, agreeing that upon completion of a housing project, a portion of the houses would be allocated to the Tamil community under LTTE supervision.

For instance, this approach proved successful in the Islamabad housing programme, which was halfway complete as of the time of the research (March–June 2006). Similarly, a housing scheme in Ninthavur followed a comparable compromise with the LTTE. According to Mohamed Mansoor, the then President of the Centre for East Lanka Social Service, 22 of the 100 houses were to be allocated to the Tamil community upon completion. This allocation was deemed reasonable because Muslims owned 80 percent of the land in the area, while Tamils owned 20 percent. At the time of the author’s fieldwork, approximately 30 houses had been completed at this site. I don’t know what happened afterward.

The second approach adopted by the people was to build houses in the areas they had lived in before the tsunami, despite construction being prohibited within 65 meters of the sea. Muslims in Marathamunai knew they would not be allocated any land for housing and sought funds from organisations such as the Eastern Human Economic Development to construct homes on their original plots. The affected individuals have made efforts to urge their leaders to engage with the TRO and the LTTE to reclaim the funds borrowed by Muslim people and organisations to purchase land. The four-acre plot that the Memon Society had acquired for housing development was sold to a Tamil organisation for Rs. 1,000,000 (roughly USD 10,000) and was one such land in question.

The national political forces operating in Ampara have deprived the poor (Muslim) fisher folk of their right to land and build houses in their villages. These communities have resorted to non-violent strategies involving accepting the status quo without questioning it and fighting for their rights. The passivity among the poor affected families is a result of them not having representation in the civil society organisations in the area. These bodies are run by elites who do not wish to contest the GoSL rule of a 65-metre buffer zone or LTTE land claims. The tsunami not only washed away the houses and took the land of the poor communities that lived by the sea, but it also made them even poorer, more marginalised, and more ethnically segregated.

Here, 20 years later, it is time that justice was done to the Muslim families in the Ampara district who were severely hit by the tsunami. It is also a significant and timely commitment made by President Dissanayake to offer 500 houses to the Muslim tsunami victims. Such a promise is overdue and essential, as these marginalised communities have desperately needed a voice and action in their favour for over 20 years. Delivery of such homes to the victims would be an important step in restoring social harmony and the dignity and livelihoods of those affected by the tragic incident.

Features

Worthless corporations, boards and authorities

Prof. O. A. Ileperuma

The Cabinet has recently decided to review the state-owned, non-commercial institutions, many of which are redundant or are of no use. The government manages 86 departments, 25 District Secretariats, 339 Divisional Secretariats, 340 state-owned enterprises and 115 non-commercial state statutory institutions. The national budget allocates Rs. 140 billion to manage these institutions.

We have inherited a large number of redundant Corporations, Boards and Authorities causing a huge drain on our financial resources. These institutions were basically created by previous governments to give jobs to defeated candidates and friends of government politicians. For instance, we have the State Pharmaceutical corporation and the State Pharmaceutical Manufacturing corporation. They can be merged. Then, we have the Coconut Development authority and the Coconut Cultivation Board, which is redundant. Decades ago, coconut cultivation came under the coconut research institute (CRI). An extension section of the CRI can easily undertake the functions of these two institutions. Another example is the still existing Ceylon Cement corporation which earlier ran two cement mills at Puttalam and Kankesanthurai. Now, the Kankasenthurai factory does not exist and the Puttalam factory is under the private sector. Still this Ceylon Cement Corporation exists and the only activity they are doing is to lease the lands for mining which earlier belonged to them. There is a chairman appointed by the minister in charge based on political connections and a general manager and a skeleton staff of about ten workers. This corporation can be easily dissolved and the Ministry Secretary can take up any functions of this corporation.

In the field of sciences, the National Science Foundation was created in 1968 to promote science and technology and to provide funding for researchers. Then a former president created two other institutions, National Science and Technology Commission (NASTEC) and National research Council (NRC). While NASTEC is tasked with science policy and NRC provides research grants; both these tasks were earlier carried out by the National Science Foundation. In the field of education, curriculum revisions, etc., were carried out earlier by the Department of Education, and later the National Institute of Education was created, and for educational policy, the National Education Commission was created. The latter was created to provide a top position for an academic who supported the then government in power.

There is a Water Supply and Drainage Board and also a separate Water Resources Board, and they can easily be amalgamated. There is also the Cashew corporation serving no useful purpose and its duties can be taken over by an institution such as the Department of Minor Crops. There is also the State Development & Construction Corporation and the State Engineering Corporation of Sri Lanka which appear to be doing similar jobs.

We still have Paranthan Chemicals Ltd., which is the successor to the Paranthan Chemicals Corporation involved in manufacturing caustic soda and chlorine. Their factory was destroyed during the war nearly 20 years ago, but it exists and its only function is to import chlorine and sell it to the Water Board for the water purification process. Why can’t the Water Board import chlorine directly?

I am aware that my views on this subject are likely to draw criticism but such redundancies are a severe drain on the Treasury, which faces the difficult task of allocating funds.

Features

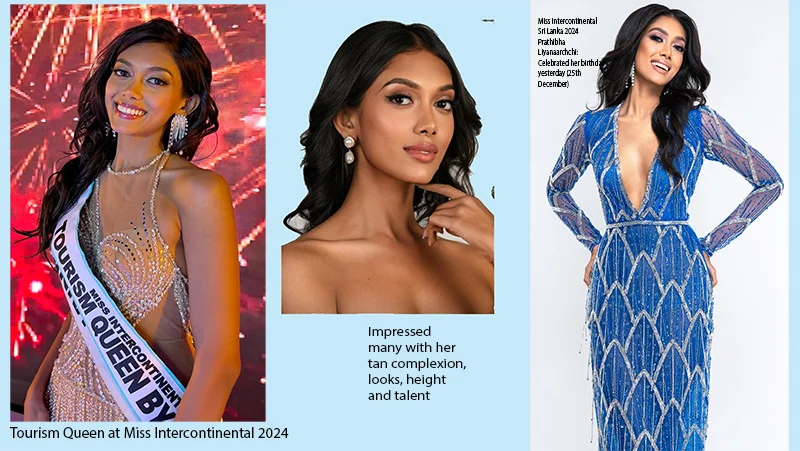

Head-turner in Egypt…

Prathibha Liyanaarchchi, Miss Intercontinental Sri Lanka 2024, is back in town after participating in the 52nd edition of Miss Intercontinental held at the Sunrise Remal Resort, Sharm El-Sheik, in Egypt.

Prathibha Liyanaarchchi, Miss Intercontinental Sri Lanka 2024, is back in town after participating in the 52nd edition of Miss Intercontinental held at the Sunrise Remal Resort, Sharm El-Sheik, in Egypt.

There were nearly two weeks of activities, connected with this event, and Prathibha says she enjoyed every minute of it.

“It was wonderful being in the company of over 52 beautiful girls from around the world and we became great friends.

“My roommate was Miss Greece. She was simply awesome and I even taught her a few Sinhala words.

“Most of the contestants were familiar with Ceylon Tea but didn’t quite know much about Sri Lanka.”

However, having won a special award at Miss Intercontinental 2024 – Queen of Tourism – Prathibha says she is seriously thinking of working on a campaign to show the world that Sri Lanka is a paradise island and that tourists would love to experience our scene.

Although our queen was not in the final list, she made it into the Top 22 and was quite a drawcard wherever she went.

“I guess it was my tan complexion and my height 5 ft. 10 inches.”

She even impressed an international audience with her singing voice; the organisers were keen to have a contestant from the Asia Oceania group showcase her talent, as a singer, and Prathibha was selected.

She sang Madonna’s ‘La Isla Bonita’ and was roundly applauded.

Even in the traditional costume section, her Batik Osariya and the traditional seven-piece necklace impressed many.

With her new buddies…at the beauty pageant

The grand finale was held on 6th December with Miss Puerto Rico being crowned Miss Intercontinental 2024.

“I would like to say a big thank you to everyone who supported me throughout this journey. I’m honoured to have been named a Top 22 Finalist at Miss Intercontinental 2024 and awarded the Special title of Miss Tourism Queen. It was a challenging yet unforgettable experience competing in Egypt. Preparing, in just three weeks, and performing, was no easy feat, but I’m so proud of what I accomplished.”

For the record, Prathibha, who celebrated her birthday on Christmas Day (25), is a technical designer at MAS holdings, visiting lecturer, model, and a graduate from the University of Moratuwa.

Unlike most beauty queens who return after an international event and hardly think of getting involved in any community work, Prathibha says she plans to continue serving her community by expanding her brand – Hoop The Label – and using it as a platform to create a positive change for the underprivileged community.

“At the same time, I am committed to furthering my education in fashion design and technology, aiming to combine creativity with innovation to contribute to the evolving fashion industry. By blending these passions, I hope to make a lasting impact, both in my community, and in the world of fashion.”

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoSri Lanka to mend fences with veterans

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoPathirana set to sling his way into Kiwi hearts

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoIs AKD following LKY?

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoOffice of CDS likely to be scrapped; top defence changes on the cards

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoSL issues USD 10.4 bn macro-linked bonds

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days ago‘A degree is not a title’ – a response

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoRanil’s advice

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoLest watchdogs should become lapdogs