Features

Amid Winds and Waves: Sri Lanka and the Indian Ocean

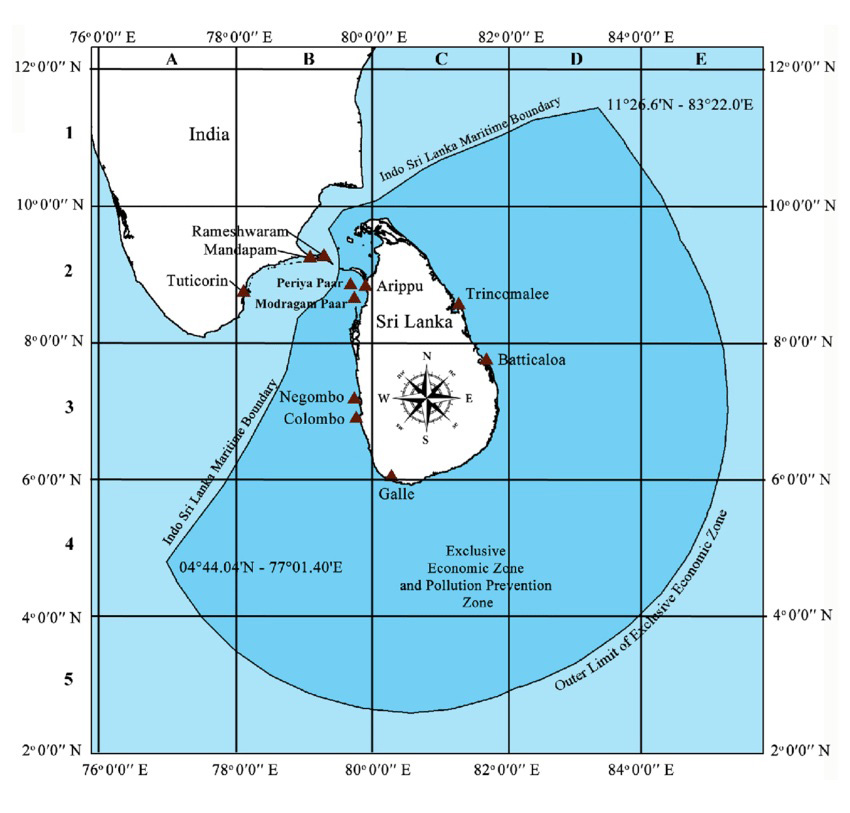

Encircled by the Afro-Asian landmass and island chains on the three sides, the Indian Ocean is a vast bay whose monsoon winds and waves have long driven connection and contestation. It has served as an interface of connectivity, a highway of communication, a protective moat, an abundant source of food, and a battleground for the political entities along its shores since the dawn of history. The Indian Ocean has always been a restless expanse of movement of ships, peoples, ideas, and ambitions. Empires once traced their boundaries across its waters; traders, monks, and migrants carried commodities, languages and faiths that wove distant shores into a single, fluid world.

Today, those same waters have re-emerged as a pivotal space of 21st century global geopolitics. New maritime corridors, naval deployments, and infrastructural projects have transformed the ocean into a living map of global security architecture. From the vantage point of Sri Lanka—an island located at the very heart of the Indian Ocean—these shifting currents of influence are neither abstract nor remote. They shape the country’s ports, diplomacy, and economy. This chapter situates Sri Lanka within the wider Indian Ocean system, introduces “currents” as a metaphor for interacting forces—geopolitical, geo-economic, and normative—and shows how a small-state perspective reframes narratives often dominated by great powers. Reading the ocean from the island reveals both the vulnerabilities and strategic possibilities that accompany life at the crossroads of the world’s most contested waters.

The pre-modern monsoon system determined the rhythm of trade, pilgrimage, and cultural exchange. Long before European colonisation, these routes sustained cosmopolitan port cities Mombasa, Aden, Calicut, Galle, and Malacca, that thrived on interdependence (Chaudhuri 1985; Hourani 1995). Before the Portuguese entered the Indian Ocean, at the turn of the 15th century, no single political power had succeeded in controlling the entire maritime space. The arrival of the Portuguese and the establishment of their naval thalassocracy marked a fundamental shift in regional security. It inaugurated the colonial phase of the ocean’s history, during which control of the sea lanes of communication (SLCs) became the central mechanism of European domination in Asia (Pearson 1987). Successive imperial powers—Portuguese, Dutch, and British—recast ancient circuits of exchange into networks of extraction and control. The British Empire, in particular, transformed the Indian Ocean into the logistical backbone of its global order, with Ceylon, which was known then, serving as a vital coaling station and communication hub

The end of formal empire after 1945 did not diminish the ocean’s strategic significance; it merely reconfigured it. Following decolonisation, the Cold War redefined the Indian Ocean as a zone of strategic contestation. The establishment of US facilities in Diego Garcia, Soviet naval build up in Aden and Berbera, and India’s regional ambitions collectively militarised the maritime space. By the late 20th century, however, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of Asia’s economies shifted emphasis from ideological rivalry to economic competition (Kaplan 2010). The Indian Ocean re-emerged as the conduit for energy supplies and trade routes sustaining global growth. The resurgence of China, the assertiveness of India, and the recalibration of US power have together reanimated this ancient arena (Brewster 2014).

Conceptualising the Currents of Power

To understand the contemporary Indian Ocean order, one must first grasp the meaning of “currents” not merely as a poetic metaphor but as an analytical tool. In the oceanic world, currents are never still; they are in constant motion, converging, diverging, and interacting across depths and surfaces. They symbolise mobility, flux, and interconnection; forces that shape without always being visible. They are once violent, once calm. The same imagery can illuminate the behaviour of power in maritime geopolitics. Power, like water, rarely moves in a single direction; it circulates, eddies, and reconstitutes itself through interaction. (Amrith 2013). It is this fluid quality of power, rather than its concentration, that defines the Indian Ocean in the 21st century. The metaphor of “currents of power” thus challenges static or territorial notions of influence. It invites us to think of the Indian Ocean not as a space divided by national boundaries but as a field of overlapping movements—military, economic, and normative—that together generate a dynamic, multipolar order. In this sense, the ocean currents provide both the material and conceptual setting for examining how power operates in motion.

The first set of currents is geopolitical—those concerned with the projection of military capability, the control of chokepoints, and the establishment of strategic presence. These are the most visible and historically entrenched expressions of power in the Indian Ocean. From the British Empire’s maritime hegemony in the 19th century to the US naval predominance after 1945, control over the ocean’s arteries has long been equated with global influence. Alfred Thayer Mahan’s classic dictum—whoever rules the waves rules the world—continues to shape strategic thinking, from Washington to New Delhi and Beijing (Holmes and Yoshihara 2008).

In the present era, geopolitical currents manifest through naval deployments, port access agreements, and strategic partnerships. The United States maintains a “constant current of change” through its Fifth Fleet operations and prepositioned assets in Diego Garcia (Kaplan 2010). China, through its expanding fleet and Belt and Road ports, seeks to secure sea lanes vital to its energy imports (Blanchard and Flint 2017). India, positioned as both resident power and regional guardian, projects influence across the Bay of Bengal and the Arabian Sea (Keerawella 2024). Russia, Japan, and European actors also contribute to this fluid equilibrium, ensuring that no single power commands the entire oceanic space. For smaller states, such as Sri Lanka, these currents pose both opportunity and constraint. Hosting a naval visit or allowing port access can yield economic and diplomatic dividends but also risks entanglement in rivalries.

If geopolitical currents represent the ocean’s hard power dimension, geo-economic currents embody its material flows—trade, investment, infrastructure, and debt. These are the currents that link harbours, supply chains, and financial systems into a single circulatory network. In many respects, these economic forces exert an even deeper influence than military ones because they shape dependency and development over time (Strange 1988).

The Indian Ocean carries nearly two-thirds of the world’s oil shipments and a third of global cargo traffic. It is through these routes that the prosperity of the 21st century travels. The competition to build and control ports, pipelines, and undersea cables—from Gwadar to Hambantota and from Mombasa to Perth—illustrates how economic and strategic motives intertwine (Chaturvedi and Okano-Heijmans 2019). Infrastructure initiatives such as China’s Maritime Silk Road, India’s Sagarmala and Security and Growth for All in the Region (SAGAR) policy, and Japan’s Partnership for Quality Infrastructure are not simply development programnes; they are instruments of influence embedded in the landscape of connectivity (Medcalf 2020).

Geo-economic currents also include financial dependencies and debt relationships. The experience of smaller Indian Ocean states—Sri Lanka, the Maldives, and others—demonstrate how investment can generate both growth and vulnerability. Ports financed through concessional loans may improve trade capacity, yet they also tie local economies to external decision-making The ocean’s economic currents, therefore, are not neutral; they flow through channels shaped by power and asymmetry (Strange 1988).

For Sri Lanka, navigating these currents demands careful balancing. The country’s position as a transshipment hub gives it leverage, but its limited domestic resources make it susceptible to external economic tides. Understanding geo-economic currents as dynamic and interdependent—rather than unidirectional—helps explain how smaller states engage in what scholars of small-state diplomacy call strategic diversification: leveraging multiple partnerships to reduce vulnerability to any single actor.

Beyond military and economic dimensions, the Indian Ocean is also traversed by normative or ideational currents—flows of values, governance models, and diplomatic norms (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Crawford 2002). These are the subtle forces that shape legitimacy and influence through persuasion rather than coercion. As Neta C. Crawford (2002) argues, moral reasoning and communicative action constitute a distinct form of power: the capacity to transform interests and behaviour through the force of argument and ethical appeal. The European Union’s emphasis on maritime governance and climate security, India’s civilisational diplomacy, and China’s narrative of South–South cooperation each represent attempts to define the moral and political tone of regional order (Acharya 2014). Soft power, as Joseph Nye (2004) famously described it, derives from attraction—the ability to shape others’ preferences through culture, ideology, or legitimacy. In the Indian Ocean, soft power travels through education, religious linkages, development aid, and multilateral diplomacy (Wilson 2015). Sri Lanka’s historical role as a Buddhist and trading crossroads offers its own reservoir of cultural soft power, even if underutilised.

Normative currents rarely flow in isolation; they interact continuously with geopolitical and economic forces, shaping and being shaped by them. In the Indian Ocean, the invocation of norms often masks underlying strategic or material interests. Freedom of navigation operations, for instance, is framed as defences of international law and the liberal maritime order, yet they also reaffirm the naval pre-eminence of established powers and signal deterrence to rivals (Finnemore and Sikkink 1998; Holmes and Yoshihara 2008). Likewise, development aid and infrastructure financing are presented as altruistic contributions to regional growth but frequently serve to open markets, secure influence, and extend spheres of access (Baldwin 2016; Strange 1988). As Neta C. Crawford (2002) reminds us, the power of norms lies not only in their moral appeal but also in the ways they are invoked, contested, and instrumentalised through political argument.

The interplay among these currents—material and ideational, coercive and persuasive—creates the dense, dynamic texture of the contemporary Indian Ocean order. Each current strengthens, redirects, or constrains the others: geopolitical maneuvers require normative justification; economic initiatives depend on legitimacy; and moral claims often derive their potency from material capability. Understanding this circulation of power in motion—where norms, interests, and strategies coalesce—reveals how influence in the Indian Ocean is exercised less through dominance than through the continual negotiation of legitimacy, access, and authority.

Taken together, these three dimensions do not operate in isolation. They intersect and overlap, producing a dynamic system that resists simple hierarchies. A port built for commercial purposes (geo-economic) may acquire military functions (geopolitical) and be justified under the banner of regional development (normative). Similarly, a naval exercise might reinforce alliances and shared values as much as it projects force).

The result is an increasingly multipolar oceanic order—one in which no single state can dominate all currents simultaneously (Acharya 2014). Instead, power is distributed through networks of cooperation, competition, and mutual dependence. For small and middle powers, this interpenetration creates spaces of maneuver. Rather than choosing between great powers, they can participate in multiple currents, aligning selectively while maintaining autonomy. This form of pragmatic engagement characterises much of Sri Lanka’s contemporary diplomacy: a continual act of navigation through convergence and counter-current.

The Historical Rhythm

Sri Lanka occupies what may be called the strategic fulcrum of the Indian Ocean—a small island astride the principal east–west maritime artery linking the Strait of Hormuz to the Strait of Malacca. Its proximity to India, its deep-water harbours, and its access to major sea lanes confer both opportunity and vulnerability. Geography has made Sri Lanka simultaneously participant and prize in the oceanic power game: the same sea that connected it to the wider world also exposed it to successive waves of conquest, commerce, and competition.

Yet geography alone does not constitute power. It frames possibilities rather than dictating outcomes. The interaction between location and agency—between spatial position and political choice—determines whether the island becomes a corridor, a crossroads, or a captive of external forces. Understanding Sri Lanka’s strategic dilemmas, therefore, requires situating policy within this enduring geography of exposure.

Long before the arrival of European powers, Sri Lanka served as a vital node in the Indian Ocean’s pre-modern trading system. Known to Greek, Roman, Arab, and Chinese mariners for its cinnamon, pearls, and gemstones, the island linked the Red Sea to the South China Sea. Ports such as Mantai and Galle functioned as entrepôts where monsoon winds carried not only goods but also religions, technologies, and languages. This dual process of receiving and transmitting influence embedded Sri Lanka in the wider Indian Ocean cosmopolis.

The European intrusion in the 16th century transformed this fluid commercial world into a theatre of imperial rivalry. As Colvin R. de Silva (1953) aptly observed, the Portuguese—who were striving to command Indian Ocean trade by controlling its routes—were brought to the island by the vagaries of wind and waves in the early 16th century. The Portuguese, the Dutch, and finally the British successively recognised the island’s maritime centrality. Under British rule, Ceylon became a keystone of the empire: its harbours—especially Trincomalee and Colombo—served as vital coaling and refitting stations on the route between Suez and Singapore. The construction of Colombo Harbour in the late 19th century, coinciding with the rise of steam navigation and telegraphic communication, anchored the island firmly within Britain’s imperial “lifeline.”This colonial experience embedded a dual legacy: integration into global networks and exposure to external control. Control of the island equated to control of regional sea lanes—a reality that continues to shape strategic perceptions today.

The succession of European empires—Portuguese, Dutch, and British—transformed Sri Lanka’s maritime geography into a mechanism of control. The Portuguese first recognised its harbours as waypoints for the spice trade and fortified coastal towns to secure sea lanes to the East. The Dutch refined this logic, converting the island into a nodal point in their Indian Ocean trading network. For the British, Ceylon became a keystone of empire: its ports at Trincomalee and Colombo served as vital coaling stations on the Suez–Singapore route.

This long experience of being used rather than choosing in global strategy embedded a structural ambivalence toward external power. It cultivated a normative orientation that prized independence, neutrality, and moral legitimacy as shields against domination. When post-colonial leaders later championed non-alignment and the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace, they were, in effect, translating colonial memory into diplomatic doctrine. Geography had rendered the island visible; history had made its people wary. Thus, Sri Lanka’s contemporary strategy—balancing engagement with autonomy—cannot be understood without reference to the colonial imprint that both globalised and constrained it.

When Sri Lanka gained independence in 1948, it inherited not only the infrastructure but also the strategic consciousness of the empire. The early Cold War years turned the Indian Ocean into an arena of superpower rivalry, even as decolonisation swept across Asia and Africa. For Colombo, the central question was how to preserve autonomy in a world where global power blocs were rapidly forming.

Sri Lanka’s diplomatic identity first took shape in this immediate post-war Asian awakening. Even before formal independence, Ceylon participated in the Asian Relations Conference in New Delhi (March 1947)—a gathering convened by India’s Jawaharlal Nehru to imagine a post-colonial Asian order founded on peace, cooperation, and freedom from imperial domination. The Ceylon delegation, led by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, was among the most articulate advocates of regional solidarity, emphasising that Asia’s reemergence must rest on moral and cultural foundations rather than military power. This early participation signalled Sri Lanka’s aspiration to act not merely as a small state but as a moral voice within the decolonising world.

The next milestone came with the Colombo Powers Conference of 1954, which brought together leaders from Ceylon, India, Burma, Indonesia, and Pakistan. Meeting in the wake of the Korean War and the first Indochina crisis, the Colombo Powers sought to craft a collective Asian position that resisted alignment with either superpower bloc. For Sri Lanka—then under Prime Minister Sir John Kotelawala—the meeting represented both continuity with its idealist beginnings and the start of pragmatic regional diplomacy. The Colombo Powers communiqué, balancing calls for disarmament with appeals for peaceful coexistence, foreshadowed the principles that would later underpin the Non-Aligned Movement.

The Bandung Conference of 1955 further consolidated this trajectory. Although Sri Lanka’s material power was limited, its participation alongside India, Indonesia, and Egypt reaffirmed its commitment to Afro–Asian solidarity and the pursuit of an independent foreign policy rooted in moral legitimacy. The Bandung spirit—cooperation, sovereignty, and resistance to neo-colonialism—resonated deeply in Colombo’s evolving worldview.

Thus, by the time Sri Lanka hosted the 1976 Non-Aligned Summit, its role was not incidental but the culmination of three decades of intellectual and diplomatic engagement. Non-alignment was not a borrowed doctrine; it was the institutionalisation of an outlook forged in the crucible of Asia’s post-colonial rebirth.

This stance was not merely rhetorical. Sri Lanka’s advocacy of the Indian Ocean as a Zone of Peace, proposed at the United Nations in 1971, reflected a synthesis of these experiences: the conviction that security in the region could only be achieved through demilitarisation, dialogue, and balance. Yet, as the Cold War’s naval build-up intensified—from US bases in Diego Garcia to Soviet forays in the Arabian Sea—neutrality became both necessary and precarious.

The end of the Cold War temporarily reduced global attention to the Indian Ocean, but the rise of Asian economies in the 1990s and 2000s revived its centrality. As energy flows and trade routes expanded, Sri Lanka once again became a point of convergence. However, domestic civil conflict (1983–2009) diverted national focus inward even as foreign interest intensified.

The post-war period saw renewed geo-economic engagement—most visibly through large-scale infrastructure projects such as Hambantota Port and Colombo Port City, financed primarily by Chinese loans. These ventures tied Sri Lanka to Beijing’s Maritime Silk Road, prompting concerns about debt and strategic dependence. India, Japan, and the United States responded with their own initiatives, reactivating the familiar pattern of competing currents around the island.

The recent shift in discourse from “Indian Ocean Region” to “Indo-Pacific” has reframed Sri Lanka’s strategic environment. The new terminology—advanced by the United States, Japan, and Australia—integrates the Indian and Pacific Oceans into a single theatre of competition. For Sri Lanka, this dual exposure is both opportunity and risk. The Indo-Pacific framework enhances the island’s visibility as a maritime partner but also risks subsuming the Indian Ocean’s unique history within broader geopolitical rivalries.

A distinctly Sri Lankan perspective insists on viewing the Indian Ocean as an autonomous system with its own rhythms and interdependencies. In this view, smaller states are not passive bystanders but interpretive actors capable of reading and adjusting to global currents. Geography grants visibility; policy must grant resilience.

The metaphor of “currents of power” offers an analytical lens through which to interpret Sri Lanka’s experience. Military, economic, and normative forces intersect tangibly in its harbours, foreign policy, and diplomatic balancing acts. From colonial forts to modern port cities, each epoch has left its imprint on the island’s coastline.

By reading the ocean from the island, we re-centre maritime geopolitics around those states whose choices are most constrained yet most revealing. The Indian Ocean’s story is not solely that of great powers and naval empires—it is equally the story of small nations navigating vast systems. Sri Lanka’s challenge, as history suggests, is to convert exposure into advantage: to remain agile within a world of shifting tides. (Part II to be published tomorrow)

by Prof. Gamini Keerawella

It has always been a restless giant, this Indian Ocean: beautiful,

violent, and often mystifying. But today, symbolically at least, it simmers as never before.

Bert McDowell, National Geographic (1981)

Features

The world welcomes senior home buyers while Sri Lanka shuts the door at 60

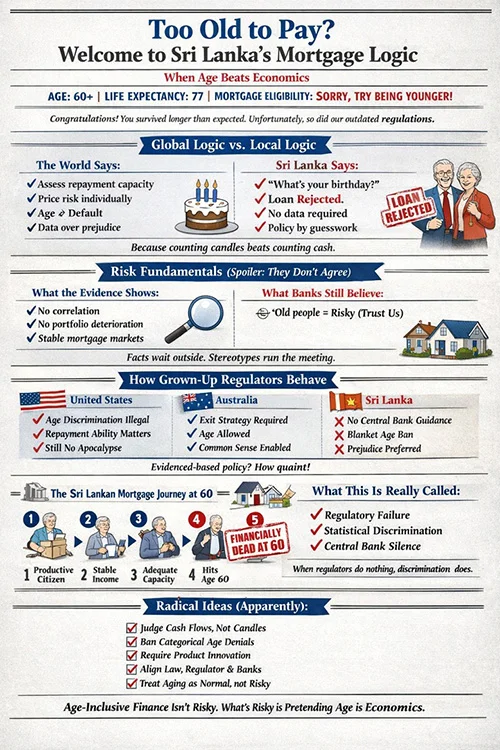

Imagine you are 58 years old, financially stable with a decent pension plan, and finally ready to build your dream home in the suburbs of Colombo. You walk into a bank, application in hand, only to be told: “Sorry, your repayment period would extend past 60. We can’t help you”. In Sri Lanka, this scenario plays out daily, leaving thousands of mature, creditworthy citizens locked out of homeownership. But, step outside our shores, you’ll find a drastically different story.

Imagine you are 58 years old, financially stable with a decent pension plan, and finally ready to build your dream home in the suburbs of Colombo. You walk into a bank, application in hand, only to be told: “Sorry, your repayment period would extend past 60. We can’t help you”. In Sri Lanka, this scenario plays out daily, leaving thousands of mature, creditworthy citizens locked out of homeownership. But, step outside our shores, you’ll find a drastically different story.

From the gleaming towers of Singapore to the countryside cottages of the United Kingdom, older borrowers aren’t just tolerated; they’re actively courted by lenders who understand that age doesn’t determine creditworthiness. While Sri Lankan banks remain trapped in outdated policies that effectively discriminate against anyone over 50, the rest of the world has moved on, creating flexible, dignified pathways for seniors to access home loans.

Role of the Central Bank and the Government

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka has failed in its fiduciary duty by not directing financial institutions to refrain from arbitrarily denying home loans, solely on the basis of age. The Ministry of Finance, therefore, the government, is equally responsible for this failure.

This regulatory vacuum enables systematic discrimination against creditworthy older citizens, contradicting modern banking principles and harming an ageing population desperately needing progressive, not punitive, financial policies.

The Global Picture: Where Age is Just a Number

Many advanced economies, such as the United States and Canada, etc., there is no maximum age limit, whatsoever, for obtaining a 30-year mortgage. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act explicitly prohibits age discrimination, meaning an 80-year-old American can walk into a bank and apply for the same three-decade loan term as a 30-year-old, provided they meet income and credit requirements. Lenders evaluate based on current financial stability, not birth certificates. A 65-year-old Canadian with a solid pension can secure a mortgage extending well into their seventies, with the understanding that income, not age, determines repayment capacity.

Australia sets the typical retirement age benchmark at 65-75, and borrowers, over 65, can still obtain mortgages by demonstrating an exit strategy; a credible plan for repayment that might include downsizing, superannuation funds, or ongoing retirement income. The system acknowledges that life doesn’t end at 60, and neither should financial opportunity.

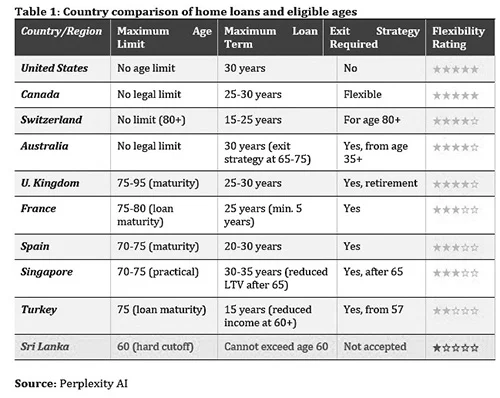

Global Home Loan Conditions:

A Comparative Analysis

The following table ranks countries from most to least affordable for older home loan applicants, based on maximum age limits, flexibility of terms, and accessibility of financing (Table 1).

What Makes These Systems Work?

The countries at the top of our affordability ranking share several key characteristics. First, they recognise that retirement doesn’t mean financial incapacity. Banks in these countries evaluate total financial health, not just employment status.

Second, they embrace the concept of exit strategies, in Australia, for instance, acceptable exit strategies include downsizing property, selling investment assets, or using superannuation (retirement) funds. These strategies are actually considered and evaluated, not dismissed out of hand. Australian lenders assess whether someone’s superannuation balance is sufficient to clear the debt, or if their investment property provides adequate cash flow. It’s a conversation, not a closed door.

Third, many of these countries offer specialised products for older borrowers. The UK, for example, has retirement interest-only mortgages where borrowers pay only interest during their lifetime, with the principal cleared when the property is eventually sold.

Australia provides reverse mortgages for those aged 60 and above. Under this arrangement, the bank pays the homeowner, rather than the homeowner paying the bank, using the house as security. The full outstanding balance is then recovered when the property is eventually sold.

These may not be perfect solutions, but they represent creative thinking about how to serve an ageing population’s housing needs.

The Hidden Cost of Age Discrimination

Sri Lanka’s rigid age-60 cutoff carries consequences that ripple far beyond individual borrowers. In a nation where life expectancy now exceeds 77 years, we’re telling people they are 17 years of ‘too old’ to be trusted ahead of them. This isn’t just unfair; it’s economically counterproductive.

Consider the broader impact. Sri Lanka has one of Asia’s fastest-aging populations. By 2050, one in four Sri Lankans will be over 60. These aren’t economic liabilities; many are professionals with decades of experience, stable incomes, and substantial assets. A 58-year-old doctor with thriving practice and pension security poses less default risk than a 28-year-old in an uncertain job market, yet our banking system treats them as if the opposite were true.

Learning from Singapore: A Regional

Success Story

We don’t need to look to distant Western nations for alternatives. Singapore, our regional neighbour facing similar demographic challenges, has crafted a more balanced approach. While Singapore’s Monetary Authority hasn’t imposed a hard age limit, banks do apply careful scrutiny to loans extending past age 65.

A Singaporean borrower, over 65, can still obtain financing, but with reduced loan-to-value ratios. If you’re buying a property worth one million dollars and you’re under 65, you might borrow up to 75 percent. Over 65, that drops to 60 percent. It’s more conservative, certainly, but it preserves opportunity.

This approach acknowledges risk without eliminating possibility. It says to older borrowers: Yes, we’ll lend it to you, but we need you to have more equity in the game. Compare this to Sri Lanka’s approach, which effectively says: “We don’t care how much equity you have or how stable your income is, you’re too old”.

A Path Forward for Sri Lanka

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka could issue guidelines similar to Singapore’s loan-to-value adjustments. For borrowers whose loan terms extend past 65, reduce the maximum LTV from 90 percent to 70 or 75 percent.

The Central Bank of Sri Lanka could issue guidelines similar to Singapore’s loan-to-value adjustments. For borrowers whose loan terms extend past 65, reduce the maximum LTV from 90 percent to 70 or 75 percent.

This protects banks from excessive risk while allowing creditworthy older borrowers to access financing. It’s a middle ground that respects both prudent lending standards and individual dignity.

Additionally, Sri Lanka could develop specialised products for its ageing population. Retirement interest-only loans, similar to those in the UK, could serve retirees who have substantial home equity but limited monthly income. Reverse mortgages, properly regulated with strong consumer protections, could help elderly Sri Lankans tap into home equity without monthly payments.

Beyond Banking: A Cultural Shift

Ultimately, changing Sri Lanka’s approach to older borrowers requires more than policy adjustments; it demands a cultural reckoning with how we value our ageing citizens. The countries that lead in age-friendly lending, the United States, Canada, Australia, share a broader commitment to recognising that people can remain economically active and financially responsible well into their later years.

These nations have moved beyond viewing retirement as an endpoint and recognised it as a transition. A 65-year-old today might have 20 or more active years ahead, years in which they’ll continue working part-time, managing investments, drawing stable pensions, and yes, making mortgage payments. Our banking sector needs to catch up to this reality.

Conclusion: Time for Change

As our table demonstrates, Sri Lanka stands alone at the bottom of the global ranking for age-friendly home lending. We’re more restrictive than Turkey with its 15-year maximum terms, more inflexible than Singapore with its sliding loan-to-value scales, and incomparably more rigid than the United States, Canada, or Switzerland, where age barely factors into lending decisions at all.

This isn’t about being soft on risk or abandoning prudent lending standards. Countries with no age limits still assess income, evaluate debt-to-income ratios, and verify creditworthiness. They simply don’t use age as a crude proxy for financial competence. The initiative lies with the Ministry of Finance, which must direct the Central Bank accordingly.

For Sri Lanka’s 58-year-old aspiring homeowner, the current system isn’t just frustrating; it’s a form of systematic discrimination that would be illegal in most developed economies. As our population ages and life expectancy increases, maintaining this policy becomes increasingly untenable. The question isn’t whether Sri Lankan banks will change their approach to older borrowers, but when and how many dreams will be deferred or destroyed in the meantime.

The world has shown us better ways forward. It’s time Sri Lanka joined the 21st century in recognising that 60 isn’t the end of financial opportunity for many, it’s just the beginning.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Securing public trust in public office: A Christian perspective – Part II

This is an adapted version of the Bishop Cyril Abeynaike Memorial Lecture delivered on 14 June 2025 at the invitation of the Cathedral Institute for Education and Formation, Colombo, Sri Lanka.

(Continued from yesterday)

The public are entitled to expect their public servants to be intrinsically committed to the truth. From a consequentialist perspective, to secure public trust, public office must be oriented towards justice. Public officers ought to lend their mind to responding to the injustices that they can address within their mandate. This is precisely what Lalith Ambanwela did. His job was to audit the accounts, which he did truthfully and thereby revealed injustices. If he had paused to worry about the risks involved or if he had wondered whether he could have rid the entire system of corruption, the obvious answer to that would have stopped him from taking any truthful action. Rather, he responded to the injustice that he saw, in a truthful manner, thereby improving the trust the public could have in his office.

Notwithstanding the Ambanwela example, one may still ask, in a place like Sri Lanka, what is the point in a single public official being truthful in a context where the problems are institutional, systemic, generational and entrenched – such as corruption or abuse of power? Many of us are familiar with the line of reasoning which suggests that there is no point in being truthful as a single individual, at any level of public service- there will be no impact except for trouble and stress; that one person cannot change systems; that one must wait for a more suitable time; that one must be strategic; that one must think of one’s children safety and future; and that one must be cautious and not attract trouble. Women, in particular, are told – do not be difficult or extreme, just let this go because you cannot change the world.

This is where we come back to the intrinsic justification for truthfulness and a Christian perspective helps us understand the need to cultivate such an intrinsic motivation. The commitment to truthfulness, the Christian faith suggests, is not subject to whether the consequences are palatable or not, as to whether you may be successful or not, but rather, regardless of those consequences. But to sustain such a commitment to truthfulness, I think we need a nurturing environment – a point which I do not have time to speak to today.

Before moving to the second attribute, which is rationality, I want to mention a few other points that I will not be dealing with today. We need to acknowledge that there can be different approaches to discovering the truth and there can be, at least in some instances, different truths. This is reflected in the fact that we have four Gospels that account for the life and ministry of Jesus, reminding us that pursuing the truth has its own in-built challenges. Furthermore, truth is inter-dependent with many other attributes, including trust and freedom.

·

1. Rationality

I now turn to rationality, the second attribute that I think is necessary for securing public trust in public office. In public law, which is the area of law that I specialise in, rationality is a core value and a foundational principle. In contrast, it is fair to say that religion is commonly understood as requiring a faith-based approach – often considered to be the anti-thesis of rationality. However, the creation account in the Bible suggests to us that we were created in the image of God and that at least one of the attributes of human nature is rationality. Furthermore, it has been argued that even Science, generally considered to be a discipline based on rationality and objectivity, is also ultimately based on assumptions and therefore on belief. A previous lecture in this lecture series, by Prof Priyan Dias, explored these ideas in detail.

In my study of public law and in my own experiences in exercising public power, I have observed, of myself and of others like me, that cultivating rationality and maintaining a commitment to it, is a challenge. The need for rationality arises when we are given discretion. Academics, for instance, are given discretion in grading student exams or when supervising doctoral students. Members of the judiciary exercise significant discretion in hearing cases. In Sri Lanka’s Constitutional Council, the members have discretion to approve or disapprove the nominations made by the President to constitutional high office including to the office of the Chief Justice and Inspector General of Police. As I mentioned earlier, where there is discretion, the law requires the person exercising that discretion to be rational.

How should public officials practice rationality? In my view, there are five aspects to practicing rationality in decision-making. First, public officials ought to be able to think objectively about each decision they are required to make. Second, to think objectively, we have to be able to identify the purpose for which discretionary power has been given to us. Third, where necessary, we ought to consult others and/or seek advice and fourth, we have to be able to resist any pressure that might be cast on us, to be biased. Fifth, we should have reasons for our decision and consider it our duty to state those reasons to the world at large.

Let me say a bit more about these five aspects. When, as public officials, we exercise discretionary power, we ought to cultivate the habit of separating the personal from the professional. In public law we say that we should adopt the perspective of a fair minded and reasonable observer. But we know that our own situations often shape even our very idea of objectivity. For example, if a decision-making body comprises only men, or if a public institution has been only headed by men or has very few women at decision-making levels, objectivity could very well lead to decision-making that does not take account of the different issues that women face. All this to say, that objectivity is not simply the absence of personal bias but a way of making decisions where a public official is committed to taking account of all relevant perspectives and thinking rationally about them. No easy task, but that, I think, is what is required of public officials who seek to secure public trust.

The second aspect to rationality is having an appreciation and commitment to the purpose for which discretion has been vested in us. To do so, as public officials, whether we like it or not, we need to have some appreciation for the legal or policy basis on which discretionary power has been vested in us. You may think that this makes the job easier for lawyers. Well, I can tell you that it has not been uncommon for me to be in decision-making situations where even lawyers do not know or have not done their homework to understand what the law requires of us. Recall here the second example I cited, that of Thulsi Madonsela, the former Public Protector of South Africa. She was very clear about the purpose of her office – to ensure accountability. The rationality of her reports on the excessive spending on the President’s house and the report on state capture, have withstood the test of time and spoken truth to power, rationally.

Permit me to make a further point here. The law itself can, and, sometimes is, unjust or unclear. In such contexts, what is the role of a public official? In Sri Lanka, only the Parliament can change laws. Those who hold public office and who derive power from a specific law can only implement it. But and this is very significant, almost always, public officials are required to interpret the law in order to understand its purpose, scope etc. For instance, in Sri Lanka, the law does not lay down the minimum qualifications for several key constitutional offices. The nomination of persons to these offices is through a process of convention, that is to say practice. In my view, this is far from desirable. However, while the law remains this way, the President has the discretion to nominate persons to these constitutional offices and the Constitutional Council is required to approve or disapprove such nominations. The lack of clarity in the relevant constitutional provisions casts a heavy duty on both the President and the Constitutional Council to ensure that they all exercise the discretion vested in them, for the purpose for which such discretion has been given. To do so, both the President and the Council ought to have an appreciation for each of these constitutional high offices, such as that of the Attorney-General or Auditor General and exercise their discretion rationally for the benefit of the people.

Consulting relevant parties and obtaining advice is the third aspect of rationality that I identified. It is not unusual for public officials to consult or obtain advice. Complex decisions are often best made with feedback from suitably qualified and experienced persons. who will share their independent opinion with you and where necessary, disagree with you. However, what I have observed in my work so far is the following. Public officials who seek advice, often select other public officials or experts who they like, or ones with whom they have a transactional relationship or ones who may not think differently from them. Correspondingly, the advice givers, often public officials themselves, seek to agree and please (or even appease) rather than give independent, subject based rational advice. This type of advice subverts the purpose of the law, bends it to political will and is disingenuous. I am sure, we can all think of examples from Sri Lanka where this has happened, sometimes even causing tragic loss of life or irreversible harm to human dignity.

Permit me to give you a personal example which is now etched in my mind. In November, 2023, the then President proposed to the Parliament that due to the non-approval of a nomination he had made to judicial office, that a Parliamentary Select Committee should be appointed to inquire into the Constitutional Council (The Sunday Times 26 November 2023). Feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of being hauled before a Parliamentary Select Committee while also recalling experiences of some public officials before such proceedings, the day after this announcement was made, I sat at my desk and typed out my letter of resignation (Daily Mirror 23 November 2023). I then rang up one of my lawyers to discuss this. I told him that I am resigning as I could not take what was to come. He responded very gently and made two points: 1) that I ought to not resign and need to see this through, whatever the process might entail and 2) that he and others will stand by me every step of the way. As you can imagine, that was not what I wanted to hear and it distressed me even more. Today, I recall that conversation with much humility and appreciation. That advice was certainly not what I wanted to hear that night but most certainly what I needed to hear.

The fourth aspect of rationality is resisting pressure which I will address later.

I will only speak briefly on the fifth aspect of rationality – that of having and stating reasons for decisions. In my view, if a public official is not able to provide reasons for a decision, it is a good indication of the need to rethink that decision. The external dimension of this aspect is one we all know. When a public official exercises public power, they are obliged to explain the reasons for their decisions. This is essential for securing the trust of the people and they owe it to us because they exercise public power, on our behalf. It goes without saying that public officials and the public should know the difference between rational reasons and reasons which are disingenuous – reasons which seek to hide rather than reveal.

So, to sum up on the points I made about rationality, I highlighted five features of this attribute, being objective in decision-making, being limited and guided by the purpose for which discretionary power has been given, consulting and/or seeking honest and expert-based advice, resisting any pressure to be biased and recording reasons for decisions. (To be continued)

by Dinesha Samararatne

Professor, Dept of Public & International Law, Faculty of Law, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka and independent member, Constitutional Council of Sri Lanka (January 2023 to January 2026)

Features

From disaster relief to system change

The impact of Cyclone Ditwah was asymmetric. The rains and floods affected the central hills more severely than other parts of the country. The rebuilding process is now proceeding likewise in an asymmetric manner in which the Malaiyaha Tamil community is being disadvantaged. Disasters may be triggered by nature, but their effects are shaped by politics, history and long-standing exclusions. The Malaiyaha Tamils who live and work on plantations entered this crisis already disadvantaged. Cyclone Ditwah has exposed the central problem that has been with this community for generations.

A fundamental principle of justice and fair play is to recognise that those who are situated differently need to be treated differently. Equal treatment may yield inequitable outcomes to those who are unequal. This is not a radical idea. It is a core principle of good governance, reflected in constitutional guarantees of equality and in international standards on non-discrimination and social justice. The government itself made this point very powerfully when it provided a subsidy of Rs 200 a day to plantation workers out of the government budget to do justice to workers who had been unable to get the increase they demanded from plantation companies for nearly ten years. The same logic applies with even greater force in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah.

A discussion last week hosted by the Centre for Policy Alternatives on relief and rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah brought into sharp focus the major deprivation continually suffered by the Malaiyaha Tamils who are plantation workers. As descendants of indentured labourers brought from India by British colonial rulers over two centuries ago, plantation workers have been tied to plantations under dreadful conditions. Independence changed flags and constitutions, but it did not fundamentally change this relationship. The housing of plantation workers has not been significantly upgraded by either the government or plantation companies. Many families live in line rooms that were not designed for permanent habitation, let alone to withstand extreme weather events.

Unimplementable Promise

In the aftermath of the cyclone disaster, the government pledged to provide every family with relief measures, starting with Rs 25,000 to clean their houses and going up to Rs 5 million to rebuild them. Unfortunately, a large number of the affected Malaiyaha Tamil people have not received even the initial Rs 25,000. Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers do not own the land on which they live or the houses they occupy. As a result, they are not eligible to receive the relief offered by the government to which other victims of the cyclone disaster are entitled. This is where a historical injustice turns into a present-day policy failure. What is presented as non-partisan governance can end up reproducing discrimination.

The problem extends beyond housing. Equal rules applied to unequal conditions yield unequal outcomes. Plantation workers cannot register their small businesses because the land on which they conduct their businesses is owned by plantation companies. As their businesses are not registered, they are not eligible for government compensation for loss of business. In addition, government communication largely takes place in the Sinhala language. Many families have no clear idea of the processes to be followed, the documents required or the timelines involved. Information asymmetry deepens powerlessness. It is in this context that Malaiyaha Tamil politicians express their feeling that what is happening is racism. The fact is that a community that contributes enormously to the national economy remains excluded from the benefits of citizenship.

What makes this exclusion particularly unjust is that it is entirely unnecessary. There is anything between 200,000-240,000 hectares available to plantation companies. If each Malaiyaha Tamil family is given ten perches, this would amount to approximately one and a half million perches for an estimated one hundred and fifty thousand families. This works out to about four thousand hectares only, or roughly two percent of available plantation land. By way of contrast, Sinhala villages that need to be relocated are promised twenty perches per family. So far, the Malaiyaha Tamils have been promised nothing.

Adequate Land

At the CPA discussion, it was pointed out that there is adequate land on plantations that can be allocated to the Malaiyaha Tamil community. In the recent past, plantation land has been allocated for different economic purposes, including tourism, renewable energy and other commercial ventures. Official assessments presented to Parliament have acknowledged that substantial areas of plantation land remain underutilised or unproductive, particularly in the tea sector where ageing bushes, labour shortages and declining profitability have constrained effective land use. The argument that there is no land is therefore unconvincing. The real issue is not availability but political will and policy clarity.

Granting land rights to plantation communities needs also to be done in a systematic manner, with proper planning and consultation, and with care taken to ensure that the economic viability of the plantation economy is not undermined. There is also a need to explain to the larger Sri Lankan community the special circumstances under which the Malaiyaha Tamils became one of the country’s poorest communities. But these are matters of design, not excuses for inaction. The plantation sector has already adapted to major changes in ownership, labour patterns and land use. A carefully structured programme of land allocation for housing would strengthen rather than weaken long term stability.

Out of one million Malaiyaha Tamils, it is estimated that only 100,000 to 150,000 of them currently work on plantations. This alone should challenge outdated assumptions that land rights for plantation communities would undermine the plantation economy. What has not changed is the legal and social framework that keeps workers landless and dependent. The destruction of housing is now so great that plantation companies are unlikely to rebuild. They claim to be losing money. In the past, they have largely sought to extract value from estates rather than invest in long term community development. This leaves the government with a clear responsibility. Disaster recovery cannot be outsourced to entities that disclaim responsibility when it becomes inconvenient in dealing with citizens of the country with the vote.

The NPP government was elected on a promise of system change. The principle of equal treatment demands that Malaiyaha Tamil plantation workers be vested with ownership of land for housing. Justice demands that this be done soon. In a context where many government programmes provide land to landless citizens across the country, providing land ownership to Malaiyaha Tamil families is good governance. Land ownership would allow plantation workers to register homes, businesses and cooperatives and would enable them to access credit, insurance and compensation which are rights of citizens guaranteed by the constitution. Most importantly, it would give them a stake that is not dependent on the goodwill of companies or the discretion of officials. The question now is whether the government will use this moment to rebuild houses and also a common citizenship that does not rupture again.

by Jehan Perera

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoComBank advances ForwardTogether agenda with event on sustainable business transformation

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoRemembering Cedric, who helped neutralise LTTE terrorism

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCORALL Conservation Trust Fund – a historic first for SL

-

Opinion3 days ago

Opinion3 days agoConference “Microfinance and Credit Regulatory Authority Bill: Neither Here, Nor There”

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoA puppet show?

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days ago‘Building Blocks’ of early childhood education: Some reflections