Features

The COVID-19 Pandemic in Sri Lanka: Contextualising it geographically

By Dr. Nalani Hennayake and

Dr. Kumuduni Kumarihamy

(Continued from Friday)

The statistics and information aside, what this tells us is that the hope for immunization through a vaccine for the coronavirus could be far off than we think. Dynamics of vaccine politics exists within global politics and the capitalist economy. The Drug Controller General of India has approved the Oxford COVID-19 vaccine developed by AstraZeneca and another by the Indian manufacturer Bharat Biotech for emergency care. During his recent visit to Sri Lanka, India’s Foreign Minister had pledged that India would prioritize Sri Lanka when supplying vaccines to other countries. In the same meeting, the Indian Foreign Minister had reiterated “India’s backing for Sri Lanka’s reconciliation process and an ‘inclusive political outlook’ that encourages ethnic harmony while the Sri Lankan Foreign Minister rejoiced in the merits of ‘Neighbourhood First Policy’.” At the same time, it was reported that Sri Lanka is making plans to sign an agreement to secure the COVID-19 vaccine through the COVAX facility, which is already approved by the Cabinet.

Various news reports indicate that Sri Lanka is discussing whether to obtain the vaccines from the United States, Britain, or Sputnik V vaccine from Russia. However, it is clear that Sri Lanka has entered into world politics of vaccines. Such vaccine politics tells us that we need to steadily continue controlling strategies such as social distancing, contact tracing, antigen, and PCR testing, significantly raising awareness at the micro-community level. The kind of resilience that local people display when a family member undergoes an infectious disease such as measles and mumps are remarkable. People must be reminded of their resilience and caring. The communities must be made aware of the importance of safeguarding against the coronavirus, given its increased politicization and uneven possibilities of immunization and care.

While it is difficult to anticipate an equitable distribution of the vaccines globally, Sri Lanka’s situation will be determined by the number of vaccines received and the pandemic’s increased politicization. The WHO recognizes four categories of vulnerable persons/groups: Persons at risk of more serious illness from COVID-19, persons or groups with social vulnerabilities, persons or groups living in closed settings, and persons or groups with a higher occupational risk of exposure to the virus. What guarantees that these groups will be considered on a priority basis and the process of immunization will not be biased towards economic and political power? The global geographies of vaccines communicate to us two important messages. First are the difficulty and the disadvantaged position of obtaining vaccines for Sri Lanka as a less-developed country, and as a result, the COVID-19 pandemic can be protracted. Until the vaccines are obtained and a sizeable population of, at least, the risk category – including the frontline health care and security personal – are immunized, we will automatically be identified as vulnerable territories in terms of bio-security. Second, this vulnerability can be manipulated politically, both globally and nationally, to negotiate other deals with powerful countries to trade with vaccines.

The possibility of uneven geographies of care is a fact that should be anticipated given that a majority of the infected are from what we call ‘low-income, low-social status’ communities. There is now a tendency to identify COVID-19 as a disease of the impoverished. The local government bodies such as Municipal councils must reevaluate their position, not how they have acted to control the pandemic, but what they have failed to do in addressing the social welfare issues of the urban low-income communities.

As we look at the possible geographies of care, it is evident that the existence of a relatively good hospital network (at national, regional, and local levels) with relatively good coverage of the entire country has been immensely helpful in treating and caring for COVID-19 patients and those suspected. In addition to the already existing hospitals, the government has converted various government institutions into treatment centres in different parts of the island. This provides breathing space for the government hospitals when dealing with COVID-19 patients and patients who need critical medical care for other illnesses. It should also not be forgotten that the Public Health Inspectors were a category of lesser-known among the hierarchy of the health workers. Their role in curtailing the COVID-19 pandemic has been indispensable: Working not under the best of circumstances and with the minimum personal protective equipment. The average labourer who was entrusted with the strenuous task of sanitizing public places must be cared for too.

The public health system operationalized through MOH areas, a total of 347 MOH areas, as per the Annual Health Statistics Report 2017, is an essential component of controlling the pandemic now or in the future. The health sector generally receives only 1.59 percent of the GNP and 5.94 percent of the National Expenditure, a measly share for an essential sector. According to the same Report, Sri Lanka records an acute shortage of health personnel. There is a significant shortage of nurses and doctors: One doctor for 1083 people, one nurse per 471 people, one Public Health Midwife for 3533 people. As we look into the possible geographies of care, the significance of Primary Health Care Units, the MOH-based public health system, in maintaining a healthy country is indisputable.

Micro-geographies of COVID-19

In its interim guidance issued on May 18, 2020, the directive issued by the WHO is as follows: “Physical and social distancing measures in public spaces to prevent transmission between infected individuals and those who are not infected, and shield those at risk of developing serious illnesses. These measures include physical distancing, reduction or cancellation of mass gatherings and avoiding crowded spaces in different settings (e.g., public transport, restaurants, bars, theatres), working from home, and supporting adaptations to workplaces and educational institutions. For physical distancing, WHO recommends a minimum distance of at least one meter between people to limit the risk of interpersonal transmission.” Thus, the WHO recommendation includes two components: physical distancing of one meter between people and social distancing as much as possible in the social events, gatherings, etc.

This requirement was initially communicated as social distancing (සමාජ දුරස්ථභාවය) in Sri Lanka. The exercise of ‘physical and social distancing’ during COVID-19 reminded us of the work of two Political Geographers, Robert E. Norris, and L. Lloyd Haring. They argued that “every person has [is] a portable territory that is larger than the space s/he physically needs” (1980:9). They further wrote that “This territory is called personal space. It is similar in some ways to a political territory. Both personal space and political space are bounded, occupants of each type of space interact with each other of their kin, and uninvited intruders in both types of areas cause stress and behavioural changes within the intruded area.” It is imperative to understand that the personal space or the portable territory is unique to each individual in both size and shape, and they may vary over time and space, according to their specific individual requirements. In such a situation, how can we/how do we regiment this personal space in fear of the uninvited intruder of the coronavirus pathogen, through a standard measure of one or two meters between individuals? Until the COVID-19 pandemic emerged, this space, the portable territory of ours, had been taken for granted. We operated with a sense of relative autonomy over our portable territories. Now, we are told by the state and those in charge of controlling the pandemic how to operate these portable territories, maintaining a distance of one to two meters from each other. It is also expected that every person would carry out this ‘social distancing’ uniformly.

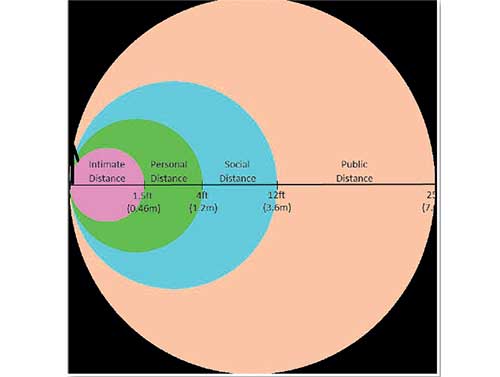

In early years, geographers were influenced by the science of spatial distancing, proxemics, introduced by the Cultural Anthropologist Edward T. Hall, who studied proxemics to understand human spatial behaviour at a micro-scale. In his famous book, “The Hidden Dimension,” published in 1966, he introduced a typology of human spatial distancing. This typology classifies the micro-spatiality of human beings into four types of spaces: intimate space, personal space, social space, and public space. Each type of space is demarcated with a specific distance, internally divided into a near phase and a far phase. The ‘portable territory’ mentioned above includes the intimate and personal spaces in this typology. According to Hall’s generalization, these portable territories end at four feet (1.2 meters), where social space begins. In his typology, ‘social space’ (See Diagram 01) spans between four to twelve feet, which is housed between personal and the public space. Edward T. Hall elaborates that “a proxemic feature of social distance is that it can be used to insulate or screen people from each other” (1966: 123). Social distance thus demarcates the end of physical dominion of an individual or, in other words, literally the jurisdiction of the portable territory.

Diagram 01: Distance Typology

In the case of COVID-19, hypothesizing that every person could be a possible carrier of the pathogen, one must maintain the one-metre distance. The distance of one-meter marks the outer boundary of the personal space and the inner boundary of the social space. An effective way to control the pathogens’ spread is to ensure that one strictly remains within one’s portable territory or, control people’s proxemic behaviour. This is very challenging since human beings have been civilized as social beings with defined and undefined social spaces!

Social distancing has become our new norm, and there is an undeniable need for this restriction. However, proxemic behaviour is not entirely an individual matter of concern. People of different cultures display different proxemic patterns; in other words, proxemic patterns are culturally highly conditioned. The concepts of ‘near’ and ‘distant’ are culturally different and relative. “The specific distance chosen (between two or more individuals) depends on the transaction, the relationship of the interacting individuals, how they feel and what they are doing… (Hall, 1969: 128). Human space requirements are generally influenced by his/her environment and surroundings and cultural norms. It is essential to understand the various elements in the immediate surroundings and the larger social context that contribute to our sense of spaces, distances, and relations. Implementers of social distancing may think that all people in a queue are potential carriers of the coronavirus, and therefore, one must maintain a distance of one meter. But some people may feel uncomfortable with social distancing simply because they may have socialized into different proxemic patterns.

Our proxemic behaviour may change, given the particular circumstances. For example, the need to feed a crying child at home, ailing parents, or one’s family overrides the fear of the virus, and the social distance is often contracted, in fear the person in front may grab what you may need. How people feel about each other at a particular time in a given space is a decisive factor in maintaining distance. In his study, Edward T. Hall explains that when people are angry and frustrated, they unknowingly tend to move closer. Some people often forget or become inconsiderate about maintaining social distance simply because of the urgency that being served in a regular queue entails. On such occasions, people are often characterized and labelled as irrational, undisciplined, and even unruly, whereas in political gatherings, opening ceremonies, personalized ‘bodhi pujas,’ etc., proxemic behaviour is often overlooked.

The standard proxemics required to control the COVID-19 pandemic are not realities for people who live in congested localities such as urban low-income areas and plantation areas where COVID-19 is fast spreading. Public services and commercial activities must be streamlined to facilitate a rational proxemic behaviour to maintain the social distance (see, for example, photograph no.1), with the understanding that the proxemic behaviour is culturally conditioned. It is very self-explanatory. Our discussion on proxemics here is not an argument against the requirement of one-meter restriction or any other form of social distancing. But understanding the cultural nuances of proxemics helps us be sensitive and intelligent when handling difficult situations rather than labelling people as irrational, undisciplined, and uncultured.

Few conclusive thoughts

What we have tried to emphasize in the article is the need and value of contextualizing the COVID-19 pandemic geographically. There are two aspects to this. First, it is imperative that the prevalence of the COVID-19 is mapped at the GN level with the available data focusing on individual MOH divisions. With our ‘sample’ exercise of Kandy, we have shown that a better spatial picture can be derived from GN level mapping. Since the MOH division, among others, is a crucial operational spatial unit for matters of public health, it is essential to map the number of COVID-19 patients at the MOH level, preferably even randomly locating them within GN divisions. The unintended benefit of such mapping would be that the existing health record systems (IMMR/eIMMR, etc.) will be further developed as a spatial health record system. A spatial health record system helps to understand the ecological dynamics of any disease and can be used as a real-time health monitoring and surveillance tool. The existing health record systems contain patients’ identity numbers (bed-head ticket number), age, gender, postal address, etc. If locational information such as GN, DSD, and district can be added, the data can easily be extracted at any spatial unit from the database for analysis in a crisis. Moreover, the postal addresses can be converted to Geographic Coordinates, indicating the patients’ geographical locations, using geocoding techniques.

Second, it is essential to understand the socioeconomic and ecological contexts of areas where the disease spreads at high intensity. Such a task is made difficult because of the unavailability of data relating to socioeconomic contexts at the GN level. However, the existing administrative system and its resources (Divisional Secretaries, Grama NIladharis, etc.) can be utilized to gather information about local areas. The process of controlling the pandemic must be localized with the MOH as the key operational spatial unit while adhering to national health guidelines and ethical concerns. It is time for the MOH-led system to take pro-active measures (i.e., creating awareness), in collaboration with the existing administrative setup, community organizations and networks, to safeguard the areas where the disease has not yet spread. Most importantly, this process needs to be monitored at the district level. Perhaps, district task forces need to be established to assess and take stock of the district’s current situation, preferably at the GN division level, and implement management and preventive measures.

In its recommendations, the WHO has repeatedly emphasized the need to adhere to both public health and social measures and, very importantly, select and ‘calibrate based on their local context.’ The WHO writes very clearly in its ‘COVID-19 Global Risk Communication and Community Engagement Strategy,’ that “COVID-19 is more than a health crisis; it is also an information and socioeconomic crisis.” It highlights the need to be ‘informed by data that cover the community needs, issues, and perceptions’ and engage with the communities. When the pandemic becomes protracted and the vaccines are not within reach, it is crucial to engage with the communities at the lower levels to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. The authorities must pay special attention to the areas that it has not yet spread and take pro-active measures to safeguard those areas, perhaps with the assistance of community organizations and institutions to create awareness among communities.

It appears that people are becoming complacent, and this can exacerbate the situation. Generally, people expect the government to control the second wave and are less inclined to take responsibility for individual behaviours and public health and social measures. On the other hand, the government seems to expect the full responsibility to be taken by the individuals. As the pandemic situation is drawn out, people tend to take risks for granted and assumes normalcy. Such complacency can be detrimental to the process of controlling the pandemic. Such complacency is also a result of poor or lack of communication about the disease, specially among vulnerable communities. Although the Ministry of Health has developed a comprehensive set of health guidelines, whether they are effectively communicated to the people is a matter of concern. Many people cannot grasp the severity of the disease and the significance of adhering to preventive health and social measures. Therefore, authorities must seriously consider sharing the responsibility of controlling the pandemic with the communities.

Finally, while we encourage mapping as a tool that can facilitate better decision making, it is important to understand that maps, and even charts and diagrams, etc., can become ‘political technologies.’ Such political technologies can instil a sense of concern, fear, and anxiety among the decision-makers and the public. We see that the pandemic is fast politicized in Sri Lanka. Mapping and geo-visualization of COVID-19 should not be ruled out either in fear of exposure or political manipulation, as it may suggest how the pandemic needs to be acted upon effectively at the local level.

Dr. Nalani Hennayake teaches a range of Human Geography courses) and Dr. Kumudini Kumarihamy teaches GIS and Health at the Department of Geography, University of Peradeniya.

(Concluded)

Features

Educational reforms under the NPP government

When the National People’s Power won elections in 2024, there was much hope that the country’s education sector could be made better. Besides the promise of good governance and system change that the NPP offered, this hope was fuelled in part by the appointment of an academic who was at the forefront of the struggle to strengthen free public education and actively involved in the campaign for 6% of GDP for education, as the Minister of Education.

When the National People’s Power won elections in 2024, there was much hope that the country’s education sector could be made better. Besides the promise of good governance and system change that the NPP offered, this hope was fuelled in part by the appointment of an academic who was at the forefront of the struggle to strengthen free public education and actively involved in the campaign for 6% of GDP for education, as the Minister of Education.

Reforms in the education sector are underway including, a key encouraging move to mainstream vocational education as part of the school curriculum. There has been a marginal increase in budgetary allocations for education. New infrastructure facilities are to be introduced at some universities. The freeze on recruitment is slowly being lifted. However, there is much to be desired in the government’s performance for the past one year. Basic democratic values like rule of law, transparency and consultation, let alone far-reaching systemic changes, such as allocation of more funds for education, combating the neoliberal push towards privatisation and eradication of resource inequalities within the public university system, are not given due importance in the current approach to educational and institutional reforms. This edition of Kuppi Talk focuses on the general educational reforms and the institutional reforms required in the public university system.

General Educational Reforms

Any reform process – whether it is in education or any other area – needs to be shaped by public opinion. A country’s education sector should take into serious consideration the views of students, parents, teachers, educational administrators, associated unions, and the wider public in formulating the reforms. Especially after Aragalaya/Porattam, the country saw a significant political shift. Disillusionment with the traditional political elite mired in corruption, nepotism, racism and self-serving agendas, brought the NPP to power. In such a context, the expectation that any reforms should connect with the people, especially communities that have been systematically excluded from processes of policymaking and governance, is high.

Sadly, the general educational reforms, which are being implemented this year, emerged without much discussion on what recent political changes meant to the people and the education sector. Many felt that the new government should not have been hasty in introducing these reforms in 2026. The present state of affairs calls for self-introspection. As members affiliated to the National Institute of Education (NIE), we must acknowledge that we should have collectively insisted on more time for consultation, deliberations and review.

The government’s conflicts with the teachers’ unions over the extension of school hours, the History teachers’ opposition to the removal of History from the list of compulsory exam subjects for Grades 10 and 11, the discontent with regard to the increase in the number of subjects (now presented as modules) for Grade 6 classes could have been avoided, had there been adequate time spent on consultations.

Given the opposition to the current set of reforms, the government should keep engaging all concerned actors on changes that could be brought about in the coming years. Instead of adopting an intransigent position or ignoring mistakes made, the government and we, the members affiliated to NIE, need to keep the reform process alive, remain open to critique, and treat the latest policy framework, the exams and evaluation methods, and even the modules, as live documents that can be made better, based on constructive feedback and public opinion.

Philosophy and Content

As Ramya Kumar observed in the last edition of Kuppi Talk, there are many refreshing ideas included in the educational philosophy that appears in the latest version of the policy document on educational reforms. But, sadly, it was not possible for curriculum writers to reflect on how this policy could inform the actual content as many of the modules had been sent for printing even before the policy was released to the public. An extensive public discussion of the proposed educational vision would have helped those involved in designing the curriculum to prioritise subjects and disciplines that need to be given importance in a country that went through a protracted civil war and continue to face deep ethno-religious divisions.

While I appreciate the statement made by the Minister of Education, in Parliament, that the histories of minority communities will be included in the new curriculum, a wider public discussion might have pushed the government and NIE to allocate more time for subjects like the Second National Language and include History or a Social Science subject under the list of compulsory subjects. Now that a detailed policy document is in the public domain, there should be a serious conversation about how best the progressive aspects of its philosophy could be made to inform the actual content of the curriculum, its implementation and pedagogy in the future.

University Reforms

Another reform process where the government seems to be going headfirst is the amendments to the Universities Act. While laws need to be revisited and changes be made where required, the existent law should govern the way things are done until a new law comes into place. Recently, a circular was issued by the University Grants Commission (UGC) to halt the process of appointing Heads of Departments and Deans until the proposed amendments to the University Act come into effect. Such an intervention by the UGC is totalitarian and undermines the academic and institutional culture within the public university system and goes against the principle of rule of law.

There have been longstanding demands with regard to institutional reforms such as a transparent process in appointing council members to the public university system, reforms in the schemes of recruitment and selection processes for Vice Chancellor and academics, and the withdrawal of the circular banning teachers of law from practising, to name a few.

The need for a system where the evaluation of applicants for the post of Vice Chancellor cannot be manipulated by the Council members is strongly felt today, given the way some candidates have reportedly been marked up/down in an unfair manner for subjective criteria (e.g., leadership, integrity) in recent selection processes. Likewise, academic recruitment sometimes penalises scholars with inter-disciplinary backgrounds and compartmentalises knowledge within hermetically sealed boundaries. Rigid disciplinary specificities and ambiguities around terms such as ‘subject’ and ‘field’ in the recruitment scheme have been used to reject applicants with outstanding publications by those within the system who saw them as a threat to their positions. The government should work towards reforms in these areas, too, but through adequate deliberations and dialogue.

From Mindless Efficiency to Patient Deliberations

Given the seeming lack of interest on the part of the government to listen to public opinion, in 2026, academics, trade unions and students should be more active in their struggle for transparency and consultations. This struggle has to happen alongside our ongoing struggles for higher allocations for education, better infrastructure, increased recruitment and better work environment. Part of this struggle involves holding the NPP government, UGC, NIE, our universities and schools accountable.

The new year requires us to think about social justice and accountability in education in new ways, also in the light of the Ditwah catastrophe. The decision to cancel the third-term exams, delegating the authority to decide when to re-open affected schools to local educational bodies and Principals and not change the school hours in view of the difficulties caused by Ditwah are commendable moves. But there is much more that we have to do both in addressing the practical needs of the people affected by Ditwah and understanding the implications of this crisis to our framing of education as social justice.

To what extent is our educational policymaking aware of the special concerns of students, teachers and schools affected by Ditwah and other similar catastrophes? Do the authorities know enough about what these students, teachers and institutions expect via educational and institutional reforms? What steps have we taken to find out their priorities and their understanding of educational reforms at this critical juncture? What steps did we take in the past to consult communities that are prone to climate disasters? We should not shy away from decelerating the reform process, if that is what the present moment of climate crisis exacerbated by historical inequalities of class, gender, ethnicity and region in areas like Malaiyaham requires, especially in a situation where deliberations have been found lacking.

This piece calls for slowing-down as a counter practice, a decelerating move against mindless efficiency and speed demanded by neoliberal donor agencies during reform processes at the risk of public opinion, especially of those on the margins. Such framing can help us see openness, patience, accountability, humility and the will to self-introspect and self-correct as our guides in envisioning and implementing educational reforms in the new year and beyond.

(Mahendran Thiruvarangan is a Senior Lecturer attached to the Department of Linguistics & English at the University of Jaffna)

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies

by Mahendran Thiruvarangan

Features

Build trust through inclusion and consultation in the New Year

Looking back at the past year, the anxiety among influential sections of the population that the NPP government would destabilise the country has been dispelled. There was concern that the new government with its strong JVP leadership might not be respectful of private property in the Marxist tradition. These fears have not materialised. The government has made a smooth transition, with no upheavals and no breakdown of governance. This continuity deserves recognition. In general, smooth political transitions following decisive electoral change may be identified as early indicators of democratic consolidation rather than disruption.

Democratic legitimacy is strengthened when new governments respect inherited institutions rather than seek to dismantle them wholesale. On this score, the government’s first year has been positive. However, the challenges that the government faces are many. The government’s failure to appoint an Auditor General, coupled with its determination to push through nominees of its own choosing without accommodating objections from the opposition and civil society, reflects a deeper problem. The government’s position is that the Constitutional Council is making biased decisions when it rejects the president’s nominations to the position of Auditor General.

Many if not most of the government’s appointments to high positions of state have been drawn from a narrow base of ruling party members and associates. The government’s core entity, the JVP, has had a traditional voter base of no more than 5 percent. Limiting selection of top officials to its members or associates is a recipe for not getting the best. It leaves out a wide swathe of competent persons which is counterproductive to the national interest. Reliance on a narrow pool of party affiliated individuals for senior state appointments limits access to talent and expertise, though the government may have its own reasons.

The recent furor arising out of the Grade 6 children’s textbook having a weblink to a gay dating site appears to be an act of sabotage. Prime Minister (and Education Minister Harini Amarasuriya) has been unfairly and unreasonably targeted for attack by her political opponents. Governments that professionalise the civil service rather than politicise them have been more successful in sustaining reform in the longer term in keeping with the national interest. In Sri Lanka, officers of the state are not allowed to contest elections while in service (Establishment Code) which indicates that they cannot be linked to any party as they have to serve all.

Skilled Leadership

The government is also being subjected to criticism by the Opposition for promising much in its election manifesto and failing to deliver on those promises. In this regard, the NPP has been no different to the other political parties that contested those elections making extravagant promises. The problem is that the economic collapse of 2022 set the country back several years in terms of income and living standards. The economy regressed to the levels of 2018, which was not due to actions of the NPP. Even the most skilled leadership today cannot simply erase those lost years. The economy rebounded to around five percent growth in the past year, but this recovery now faces new problems following Cyclone Ditwah, which wiped out an estimated ten percent of national income.

In the aftermath of the cyclone, the country’s cause for shame lies with the political parties. Rather than coming together to support relief and recovery, many focused on assigning blame and scoring political points, as in the attacks on the prime minister, undermining public confidence in the state apparatus at a moment when trust was essential. Despite the politically motivated attacks by some, the government needs to stick to the path of inclusiveness in its approach to governance. The sustainability of policy change depends not only on electoral victory but on inclusive processes that are more likely to endure than those imposed by majorities.

Bipartisanship recognises that national rebuilding and reconciliation requires cooperation across political divides. It requires consultation with the opposition and with civil society. Opposition leader Sajith Premadasa has been generally reasonable and constructive in his approach. A broader view of bipartisanship is that it needs to extend beyond the mainstream opposition to include ethnic and religious minorities. The government’s commitment to equal rights and non-discrimination has had a positive impact. Visible racism has declined, and minorities report feeling physically safer than in the past. These gains should not be underestimated. However, deeper threats to ethnic harmony remain.

The government needs to do more to make national reconciliation practical and rooted in change on the ground rather than symbolic. Political power sharing is central to this task. Minority communities, particularly in the north and east, continue to feel excluded from national development. While they welcome visits and dialogue with national leaders, frustration grows when development promises remain confined to foundation stones and ceremonies. The construction of Buddhist temples in areas with no Buddhist population, justified on claims of historical precedent, is perceived as threatening rather than reconciliatory.

Wider Polity

The constitutionally mandated devolution framework provided by the Thirteenth Amendment remains the most viable mechanism for addressing minority grievances within a united country. It was mediated by India as a third party to the agreement. The long delayed provincial council elections need to be held without further postponement. Provincial council elections have not been held for seven years. This prolonged suspension undermines both democratic practice and minority confidence. International experience, whether in India and Switzerland, shows that decentralisation is most effective when regional institutions are electorally accountable and operational rather than dormant.

It is not sufficient to treat individuals as equal citizens in the abstract. Democratic equality also requires recognising communities as collective actors with legitimate interests. Power sharing allows communities to make decisions in areas where they form majorities, reducing alienation and strengthening national cohesion. The government’s first year in office saw it acknowledge many of these problems, but acknowledgment has not yet translated into action. Issues relating to missing persons, prolonged detention, land encroachment and the absence of provincial elections remain unresolved. Even in areas where reform has been attempted, such as the repeal of the Prevention of Terrorism Act, the proposed replacement legislation falls short of international human rights standards.

The New Year must be one in which these foundational issues are addressed decisively. If not, problems will fester, get worse and distract the government from engaging fully in the development process. Devolution through the Thirteenth Amendment and credible reconciliation mechanisms must move from rhetoric to implementation. It is reported that a resolution to appoint a select committee of parliament to look into and report on an electoral system under which the provincial council elections will be held will be taken up this week. Similarly, existing institutions such as the Office of Missing Persons and the Office of Reparations need to be empowered to function effectively, while a truth and reconciliation process must be established that commands public confidence.

Trust in institutions requires respect for constitutional processes, trust in society requires inclusive decision making, and trust across communities requires genuine power sharing and accountability. Economic recovery, disaster reconstruction, institutional integrity and ethnic reconciliation are not separate tasks but interlinked tests of democratic governance. The government needs to move beyond reliance on its core supporters and govern in a manner that draws in the wider polity. Its success here will determine not only the sustainability of its reforms but also the country’s prospects for long term stability and unity.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Not taking responsibility, lack of accountability

While agreeing wholeheartedly with most of the sentiments expressed by Dr Geewananda Gunawardhana in his piece “Pharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics” (The Island, 5th January), I must take exception to what he stated regarding corruption: “Enough has been said about corruption, and fortunately, the present government is making an effort to curb it. We must give them some time as only the government has changed, not the people”

With every change of government, we have witnessed the scenario of the incoming government going after the corrupt of the previous, punishing a few politicians in the process. This is nothing new. In fact, some governments have gone after high-ranking public servants, too, punishing them on very flimsy grounds. One of the main reasons, if not the main, of the unexpected massive victory at the polls of this government was the promise of eradication of corruption. Whilst claiming credit for convicting some errant politicians, even for cases that commenced before they came to power, how has the NPP government fared? If one considers corruption to be purely financial, then they have done well, so far. Well, even with previous governments they did not commence plundering the wealth of the nation in the first year!

I would argue that dishonesty, even refusal to take responsibility is corruption. Plucking out of retirement and giving plum jobs to those who canvassed key groups, in my opinion, is even worse corruption than some financial malpractices. There is no need to go into the details of Ranwala affairs as much has been written about but the way the government responded does not reassure anyone expecting and hoping for the NPP government to be corruption free.

One of the first important actions of the government was the election of Ranwala as the speaker. When his claimed doctorate was queried and he stepped down to find the certificate, why didn’t AKD give him a time limit to find it? When he could not substantiate obtaining a PhD, even after a year, why didn’t AKD insist that he resigns the parliamentary seat? Had such actions been taken then the NPP can claim credit that the party does not tolerate dishonesty. What an example are we setting for the youth?

Recent road traffic accident involving Ranwala brough to focus this lapse too, in addition to the laughable way the RTA was handled. The police officers investigating could not breathalyse him as they had run out of ‘balloons’ for the breathalyser! His blood and urine alcohol levels were done only after a safe period had elapsed. Not surprisingly, the results were normal! Honestly, does the government believe that anyone with an iota of intelligence would accept the explanation that these were lapses on the part of the police but not due to political interference?

The release of over 300 ‘red-tagged’ containers continues to remain a mystery. The deputy minister of shipping announced loudly that the ministry would take full responsibility but subsequently it turned out that customs is not under the purview of the ministry of shipping. Report on the affair is yet to see the light of day, the only thing that happened being the senior officer in customs that defended the government’s action being appointed the chief! Are these the actions of a government that came to power on the promise of eradication of corruption?

The new year dawned with another headache for the government that promised ‘system change.’ The most important educational reforms in our political history were those introduced by Dr CWW Kannangara which included free education and the establishment of central schools, etc. He did so after a comprehensive study lasting over six years, but the NPP government has been in a rush! Against the advice of many educationists that reforms should be brought after consultation, the government decided it could rush it on its own. It refuses to take responsibility when things go wrong. Heavens, things have started going wrong even before it started! Grade Six English Language module textbook gives a link to make e-buddies. When I clicked that link what I got was a site that stated: “Buddy, Bad Boys Club, Meet Gay Men for fun”!

Australia has already banned social media to children under 15 years and a recent survey showed that nearly two thirds of parents in the UK also favour such a ban but our minister of education wants children as young as ten years to join social media and have e-buddies!

Coming back to the aforesaid website, instead of an internal investigation to find out what went wrong, the Secretary to the Ministry of Education went to the CID. Of course, who is there in the CID? Shani of Ranjan Ramanayake tape fame! He will surely ‘fix’ someone for ‘sabotaging’ educational reforms! Can we say that the NPP government is less corrupt and any better than its predecessors?

by Dr Upul Wijayawardhana

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoPrivate airline crew member nabbed with contraband gold

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoHealth Minister sends letter of demand for one billion rupees in damages

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoRemembering Douglas Devananda on New Year’s Day 2026

-

Latest News1 day ago

Latest News1 day agoCurran, bowlers lead Desert Vipers to maiden ILT20 title

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoPharmaceuticals, deaths, and work ethics

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoBellana says Rs 900 mn fraud at NHSL cannot be suppressed by moving CID against him

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoPM lays foundation stone for seven-storey Sadaham Mandiraya