Features

Difficult Dealings with Strong Political Personalities

(Excerpted from the autobiography of MDD Pieris, Secretary to the Prime Minister)

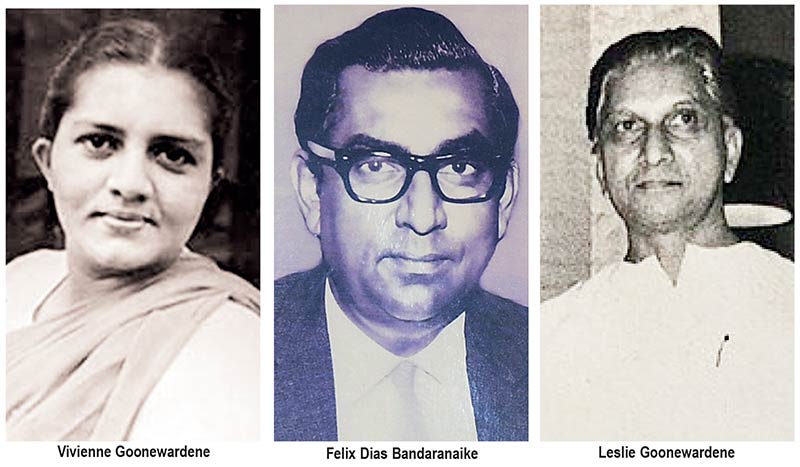

Senior public officials have often to act as buffers between ministers, other important political actors, and other stakeholders in society. On many occasions, one had to absorb a significant degree of shock and act as a facilitator, mediator or referee. A rousing example of this side of one’s responsibilities came by courtesy of Mrs. Vivienne Goonewardene, the LSSP Member of Parliament for Dehiwela-Galkissa and wife of Mr. Leslie Goonewardene, Minister of Communications.

Mrs. Goonewardene was well known for her intrepidity, straight frank discourse and a degree of rebelliousness. She rang me one day. The prime minister had apparently “interfered,” in some matter pertaining to her electorate. I received a characteristic barrage aimed at the prime minister. “Tell that woman, just because she is prime minister, she has no business to interfere in my electorate. Tell her that I am not afraid of her, and I will know what to do if she tries her nonsense with me. Now, I want you to tell her what I told you in exactly the same words,” insisted Mrs. Goonewardene.

I listened to this tirade with a degree of amusement. This was vintage Vivienne. I said “Madam, you meet the Prime Minister in Parliament. Why don’t you tell all this to her yourself’.?” This time it was my turn to get blasted. “That is none of your business. You do what is told. This is a formal request,” she replied. I then told her “Madam, if you want to use your own words, you will have to deliver them yourself. I will however, tell the prime minister that you spoke to me and that your were deeply upset about what you reported she had done in your electorate, and that as an MP you were unwilling to accept it.”

Mrs. Goonewardene was not pleased. She said, “All right, if you don’t have the guts to tell her what I have said, do it your way!” And that is what I did. I did not think it my function as a public servant to promote disharmony and spread ill will. What was relevant was that an MP was upset at a purported action of the prime minister, which it was important to bring to her attention in a suitable manner so that the issue could be addressed. Aggression and abuse would not have been helpful.

Sometimes, it becomes one’s unpleasant duty to clash with ministers, and it occasionally happens. I was Acting Secretary to the Ministry of Defence and Foreign Affairs. Mr. WT Jayasinghe and the PM were abroad. There occurred an assault on a doctor in the South, by a police constable. The doctors were naturally up in arms and wanted the constable interdicted immediately. The Inspector General of Police, Mr. Stanley Senanayake came to see me personally, and stated that there was a long standing problem between this doctor and some members of the public; that there were complaints made regarding this doctor’s behaviour in the past; that he had been rude to police officers; and that there was also some personal enmity between this doctor and the police constable.

He reported that the police were seething and did not want the constable interdicted without a full preliminary inquiry, at which they were confident the doctor’s behaviour would come to light. The IGP said that the situation was so bad, that if the constable was interdicted due to the pressure of the doctors, he might have a strike by the police of that range on his hands. I told the IGP, that if there was prima facie evidence, no matter what the reason, the constable struck the doctor, things could not be left as they were, pending a full investigation which was going to take time.

I said that at the least, the constable should be sent on compulsory leave and a full inquiry begun immediately. I also told him that there should not be any postponements and that the inquiry should be continued until it was over. I also said that in view of the high feelings on both sides, a retired judge should conduct the inquiry. The IGP agreed with some reluctance, to these instructions of mine given in my capacity as Acting Secretary, Defence.

The doctors were not happy. They were not prepared to settle for anything short of interdiction. They began to canvass Ministers, and amongst others went to Minister Felix R. Dias Bandaranaike, who, without checking with the IGP or me, and not knowing the background or the serious implications on the police side had agreed that the constable should be interdicted. The minister rang me, and in a rather peremptory tone said, “I want that policeman interdicted.” I said “I am sorry, I won’t be able to do that,” and explained the complications, and how I had already taken steps to remove the constable from the scene, by sending him on compulsory leave, in spite of the opposition of the IGP.

I also informed him that the inquiry was starting immediately. But the minister was not satisfied. He had committed himself to the doctors. He said, “All that is well and good, but unless the police officer is interdicted, you will have a doctors’ strike on your hands, and you will be responsible.” I replied that “If I order interdiction there will be a police strike on my hands, for which too I would be held responsible.” I concluded by saying that as Acting Secretary, Defence & Foreign Affairs, I had also to be concerned with the morale of the police, and that what had been worked out was a fair compromise.

The minister was not pleased. “Then, you do any bloody thing you want,” he said and slammed the phone down. Curiously, virtually these same words were used on me by a few other ministers on some future occasions, and my left ear received significant training in coping with banging telephones. Fortunately, wiser counsel prevailed and a strike either by the doctors or the police was averted. The immediate commencement of the inquiry helped.

When the PM returned to the island, I briefed her on what had happened. She backed me fully, and said that the minister had no business to get involved in an issue, which was not within his area of responsibility. In the future too, she wanted me to use my own independent judgment, on any issue which concerned her responsibilities. This was one of the main reasons why it was easy to work with Mrs. Bandaranaike. She trusted you, and backed fully whatever decision you took. She was interested in hindsight only to the extent that its contemplation could improve the quality of foresight in the future, and not to find fault.

Another strong quality of the Prime Minister was her ability to listen to a strong dissenting view, without losing her temper or later holding it against you. In any case, as far as I was concerned, I had cleared this question the first day she came to office after having been sworn in as Prime Minister, as I had related earlier in these memoirs. We had a relationship built on frank and sincere talk and discussion. I never felt inhibited to speak out when I thought it was necessary. Although I did not get involved in political comment, sometimes the sheer sycophancy one saw around provoked one to say something.

For instance, on one occasion, when the ruling SLFP had lost a by-election fairly badly, there was a political figure trying to put a gloss on it in order to please the PM. I happened to be there, and in my presence he said “But Madam, there is nothing to worry. Over 12,000 progressives voted for us. That is a great victory.” I was so irritated that I shot back, that on this calculus of the “progressive” vote for the government, it would lose every seat at the next general election. The PM, surprised, looked hard at me, and then said, “quite right.” In fact, unfortunately for the government, the next general election, illustrated my point all too comprehensively. I did not realize at the time, that what I uttered was prophetic.

The case of Mr. R. Paskaralingam

An example of the PM, and her attitude towards dissenting views, was the case of Mr. R. Paskaralingam. Mr. Paskaralingam was a colleague, in the Civil Service, senior to me in the service, and at the time Additional Secretary to the Ministry of Education. He was an experienced, unruffled and a sound administrator who bore the brunt of the general administration in a large and difficult Ministry, thus freeing the Secretary, Dr. Udagama, a distinguished educationist, to address the quality, content and scope of education at the various levels.

Unfortunately, for Mr. Paskaralingam, during this period, he had approved an officer of the Ministry going to London on a scholarship, and the officer did not return. The Minister of Public Administration, Mr. Felix Dias Bandaranaike took a dim view of this, and wrote a letter to the Prime Minister expressing extremely critical views of Mr. Paskaralingam’s negligence in permitting this officer to go.

The charge was that he was not diligent enough in checking all aspects before he gave permission.

This was also a time of stringent exchange controls, where a system of exit permits existed without which no one could travel abroad. Particularly in the climate of the time, the charge against a senior public servant of Mr. Paskaralingam’s position was serious.

I held quite a different view and I expressed it to the Prime Minister. I said that all of us in the public service work on a basis of trust as far as our colleagues are concerned. There was no way that you could look into every representation made to you by a fellow public servant. The whole administration would grind to a halt if you spent your time investigating every assertion or statement made to you. It was just not practical and I explained to the Prime Minister that Mr. Paskaralingam, who was a very busy person would have had to take his Assistant Secretary’s word in this instance. I told her that I would have done exactly the same thing.

That passed. But shortly thereafter the issue of acting arrangements in the Ministry of Education came up, since Dr. Udagama was due to go abroad. Mr. Paskaralingam was the next senior officer. The period involved was about 10 days. I therefore prepared as is customary, a letter from the Prime Minister to the President recommending his appointment as Acting Secretary. Secretaries even then were appointed by the President, on the recommendation of the Prime Minister. When I took the letter for signature, the Prime Minister said, “No, I can’t have him act. We will get a Secretary from another Ministry to act.”

I asked what the problem was. She said that some members of Parliament had made complaints to her about various transfers and so on made by him. I asked whether any of these complaints were inquired into. She said “No,” but she would have problems with the MPs, if Mr. Paskaralingam acted. I told the Prime Minister that Mr. Paskaralingam was one of the hardest worked officers. He was in office by 7.30 in the morning and on most days left after 7.30 in the night. He carried a tremendous burden of administration and was the second most senior officer in the Ministry. Acting for the Secretary, was not a favour. It was but his due.

I said that a man was entitled to the “fruits” of his labours. I also said that as Prime Minister, she should not come to any conclusions, based on what some MPs may have said, without investigating the matter and establishing its truth or otherwise. But the Prime Minister was still not convinced. She said that she would have problems with the MPs. I then said, “Excuse me,” and started walking out of the room. “Where are you going?” inquired the Prime Minister. I said, I was going to bring the seniority list of the Sri Lanka Administrative Service. “What for?” asked the Prime Minister. I said, “Madam, the government cannot have it both ways. You cannot get work out of people and not give them their due.

If you believe what the MPs have stated without any inquiry, it is obvious that you yourself have lost confidence in the person. Such an official should not be No. 2 in a Ministry as important as the Ministry of Education. Please select someone else from the seniority list and we will move out Mr. Paskaralingam immediately.” “Sit down,” the Prime Minister ordered. Then she reflected. Put this way, the Prime Minister realized that acting on a vague impression created in her mind was not in order. She signed the letter, recommending Mr. Paskaralingam as Acting Secretary, Education. I thanked the Prime Minister and reminded her that she was free to make any investigations about complaints from MPs.

I also told her that this was only one specific case, and that it was important that certain fair norms be established in regard to the interaction between political authorities and the public service, and that these be visible to the public service. This was necessary, in order to obviate frustration and produce an efficient service, which was in the interests of both the government and the country.

Speaking of Dr. Udagama, it is worth relating an amusing incident that occurred around this time. One day, I was at Temple Trees working with the Prime Minister. The time was about 2.45 p.m. On a matter arising from some of the papers I was discussing with her, she wanted to speak with Dr. Udagama. The switchboard operator was instructed to get him on the line. The operator first trying his office and being told that he could be at home, had attempted to reach him there. Soon, a hesitant and somewhat embarrassed operator came up to the Prime Minister and informed her that Dr. Udagama was at home but was having a bath!

“What! having a bath at this time?” blurted out an incredulous Prime Minister. She had a sense of humour, and the next moment observed “what a strange man!” Evidently Dr. Udagama had come home for a late lunch, and decided to take a shower before getting back. I mentioned this episode to him. We had a good laugh. Even today we sometimes laugh about this when we meet. I however had told Dr. Udagama that I have no means of describing the look on the Prime Minister’s face when she was told that her Secretary, Ministry of Education was enjoying a bath at 3 o’clock in the afternoon on a working day.

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

Features

Egg white scene …

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

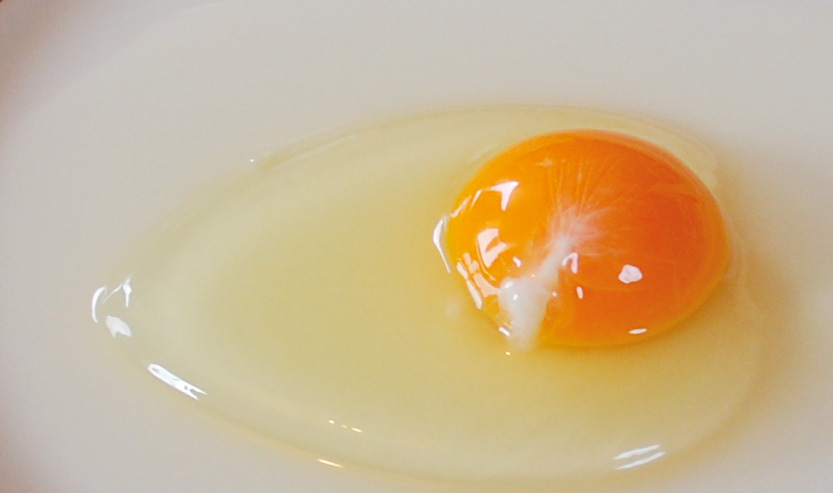

Thought of starting this week with egg white.

Yes, eggs are brimming with nutrients beneficial for your overall health and wellness, but did you know that eggs, especially the whites, are excellent for your complexion?

OK, if you have no idea about how to use egg whites for your face, read on.

Egg White, Lemon, Honey:

Separate the yolk from the egg white and add about a teaspoon of freshly squeezed lemon juice and about one and a half teaspoons of organic honey. Whisk all the ingredients together until they are mixed well.

Apply this mixture to your face and allow it to rest for about 15 minutes before cleansing your face with a gentle face wash.

Don’t forget to apply your favourite moisturiser, after using this face mask, to help seal in all the goodness.

Egg White, Avocado:

In a clean mixing bowl, start by mashing the avocado, until it turns into a soft, lump-free paste, and then add the whites of one egg, a teaspoon of yoghurt and mix everything together until it looks like a creamy paste.

Apply this mixture all over your face and neck area, and leave it on for about 20 to 30 minutes before washing it off with cold water and a gentle face wash.

Egg White, Cucumber, Yoghurt:

In a bowl, add one egg white, one teaspoon each of yoghurt, fresh cucumber juice and organic honey. Mix all the ingredients together until it forms a thick paste.

Apply this paste all over your face and neck area and leave it on for at least 20 minutes and then gently rinse off this face mask with lukewarm water and immediately follow it up with a gentle and nourishing moisturiser.

Egg White, Aloe Vera, Castor Oil:

To the egg white, add about a teaspoon each of aloe vera gel and castor oil and then mix all the ingredients together and apply it all over your face and neck area in a thin, even layer.

Leave it on for about 20 minutes and wash it off with a gentle face wash and some cold water. Follow it up with your favourite moisturiser.

Features

Confusion cropping up with Ne-Yo in the spotlight

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

At an official press conference, held at a five-star venue, in Colombo, it was indicated that the gathering marked a defining moment for Sri Lanka’s entertainment industry as international R&B powerhouse and three-time Grammy Award winner Ne-Yo prepares to take the stage in Colombo this December.

What’s more, the occasion was graced by the presence of Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports & Youth Affairs of Sri Lanka, and Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe, Deputy Minister of Tourism, alongside distinguished dignitaries, sponsors, and members of the media.

According to reports, the concert had received the official endorsement of the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau, recognising it as a flagship initiative in developing the country’s concert economy by attracting fans, and media, from all over South Asia.

However, I had that strange feeling that this concert would not become a reality, keeping in mind what happened to Nick Carter’s Colombo concert – cancelled at the very last moment.

Carter issued a video message announcing he had to return to the USA due to “unforeseen circumstances” and a “family emergency”.

Though “unforeseen circumstances” was the official reason provided by Carter and the local organisers, there was speculation that low ticket sales may also have been a factor in the cancellation.

Well, “Unforeseen Circumstances” has cropped up again!

In a brief statement, via social media, the organisers of the Ne-Yo concert said the decision was taken due to “unforeseen circumstances and factors beyond their control.”

Ne-Yo, too, subsequently made an announcement, citing “Unforeseen circumstances.”

The public has a right to know what these “unforeseen circumstances” are, and who is to be blamed – the organisers or Ne-Yo!

Ne-Yo’s management certainly need to come out with the truth.

However, those who are aware of some of the happenings in the setup here put it down to poor ticket sales, mentioning that the tickets for the concert, and a meet-and-greet event, were exorbitantly high, considering that Ne-Yo is not a current mega star.

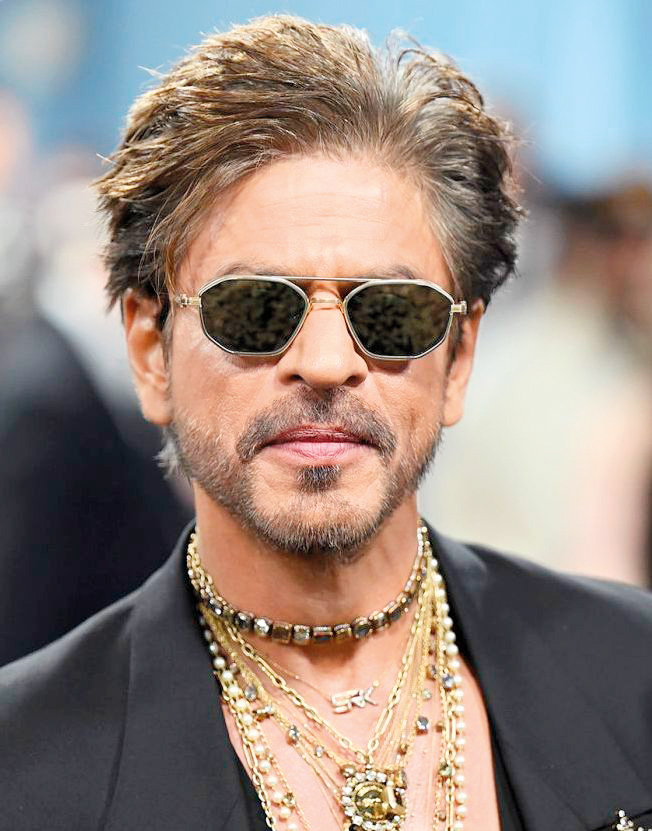

We also had a cancellation coming our way from Shah Rukh Khan, who was scheduled to visit Sri Lanka for the City of Dreams resort launch, and then this was received: “Unfortunately due to unforeseen personal reasons beyond his control, Mr. Khan is no longer able to attend.”

Referring to this kind of mess up, a leading showbiz personality said that it will only make people reluctant to buy their tickets, online.

“Tickets will go mostly at the gate and it will be very bad for the industry,” he added.

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoRethinking post-disaster urban planning: Lessons from Peradeniya

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoAre we reading the sky wrong?