Features

Transformations in Sri Lankan social sciences: From early to modern anthropology

by Amarasiri de Silva

Before the 1970s, anthropology in Sri Lanka, as an academic discipline, was relatively confined to a few studies. The country had only a few trained anthropologists, and the scope of anthropological research needed to be expanded. This reflected a broader trend in the social sciences in Sri Lanka, where subjects like sociology and anthropology are still required to be fully institutionalized or widely pursued. However, the discipline began to change significantly in the subsequent decades, particularly with the expansion of the departments of Sociology at major universities in Sri Lanka.

The expansion of the departments of Sociology in Sri Lanka’s universities was a pivotal development in the history of social sciences in the country. This expansion increased the number of students who could study sociology and diversified the subjects and research areas that could be explored within the discipline. Sociology was increasingly offered as a special degree, attracting many students interested in studying the social fabric of the country.

This shift in academic focus led to a significant increase in students pursuing higher education in sociology. After successfully completing their undergraduate degrees, with first and second classes, many of these students pursued advanced degrees, including PhDs, at prestigious universities abroad. The most common destinations for these students were India, Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States, where they could receive training in the latest methodologies and theoretical frameworks in anthropology and the social sciences.

The exposure to foreign academic environments had a profound impact on the way sociology was studied and practiced in Sri Lankan universities. Students who went abroad for their PhDs were exposed to many theoretical perspectives and research methodologies that they brought back a wealth of knowledge and expertise, which they applied to their research and teaching in Sri Lanka.

One of the most significant contributions of these post 1970 foreign-trained sociologists was their emphasis on empirical research and fieldwork, and applied orientation in research. Unlike earlier generations of sociologists and anthropologists who often relied on theoretical analysis of classical anthropology, these new scholars emphasized the importance of gathering data from the field on social change and social problems. This approach led to a surge in applied anthropological and sociological studies conducted in Sri Lankan villages, as these scholars sought to understand the social dynamics of rural life in the country.

The focus of these studies reflected both the new methodologies introduced to these scholars and the distinct social and cultural landscape of Sri Lanka. With most of the population residing in rural areas, understanding village dynamics was essential to comprehending the broader social fabric of the country. Some scholars concentrated on the intricacies of caste, while others explored the rise of class and its impact on social formation, stratification and political behaviour.

By documenting various aspects of village life—such as kinship structures, economic activities, religious practices, and social hierarchies—their research provided valuable insights into how traditional social structures were being preserved or transformed amid modernization and economic change. Additionally, some researchers turned their attention to marginalized communities, including deprived caste groups and ethnic enclaves, highlighting their unique challenges and contributions to the social structure.

The documentation of village studies also significantly impacted the development of anthropology as a discipline in Sri Lanka. Although many of these scholars identified as sociologists, their research often overlapped with anthropological concerns, particularly in their focus on culture, tradition, and social organization. As a result, the line between sociology and anthropology became increasingly blurred, leading to a more integrated approach to the study of social life in Sri Lanka.

The early anthropological and sociological research conducted in Sri Lanka during this period laid the foundation for future studies. The emphasis on fieldwork and empirical research became a hallmark of Sri Lankan sociology, and many of the methodologies and theoretical perspectives introduced by these scholars continue to influence research in the country today.

Moreover, the focus on village studies has impacted how rural life is understood in Sri Lanka. The detailed documentation of village life has provided a valuable record of the social and cultural changes that have occurred in the country over the past few decades. These studies have also contributed to a deeper understanding of how global processes, such as economic development and cultural exchange, have impacted local communities in Sri Lanka.

My Exposure to Anthropological Fieldwork

My journey into the world of anthropology began during my master’s degree research in Mirissa, a fishing village located in the southern province of Sri Lanka. Having been born and raised in an agricultural village, Batapola in the Galle District, my exposure to the coastal environment of Mirissa was an entirely new and transformative experience.

The transition from an agricultural backdrop to a coastal fishing community presented a set of unique challenges that I had never encountered before. In Mirissa, I was introduced to the intricacies of various fishing methods, a completely different form of livelihood compared to the farming practices I was familiar with. Learning about the techniques used in the capture of fish, the handling and processing of the catch, and the complex networks involved in fish marketing, crew formation, etc., required me to immerse myself deeply into the everyday lives of the villagers.

Beyond the technical aspects, understanding the lives of the fishermen and their families offered profound insights into the social fabric of coastal communities. I observed how the rhythms of life in Mirissa were intimately tied to the sea, shaping the village’s economy and the community’s cultural and social structures. The challenges faced by these families, their resilience, and how they navigated the uncertainties of their occupation became focal points of my research.

This experience in Mirissa not only broadened my understanding of Sri Lanka’s diverse socio-economic landscapes but also deepened my appreciation for the complexity and richness of anthropological research. Through this fieldwork, I realized the importance of adapting to new environments and the necessity of approaching research with sensitivity and respect for the communities involved.

One of the challenges I encountered during my research in Mirissa was establishing the parameters of social change in Mirissa, particularly with the introduction of mechanized boats, or the three-and-a-half-ton boats, which began to replace the traditional outrigger canoes with sails. It quickly became apparent that this technological shift was not merely a matter of economic or practical change but had profound social implications for the village. When mechanized boats were first introduced in the 1950s, the villagers were skeptical about the viability of this new technology. Some recipients even destroyed the freely given boats by submerging them in the sea. Out of the roughly 40 boats distributed to the deep-sea fishing community, only one remained operational at the time of my research. The others were either sold or damaged.

I observed that the village was divided into distinct social categories, based on the method of fishing. Some fished in the deep sea using mechanized boats or canoes (Ruwal oru), and those engaged in shallow sea fishing using beach seine nets (Ma Dal). These two communities, within the village, were highly divergent, with a strong sense of identity tied to their respective fishing practices.

The social divide between these groups was evident not only in their daily activities but also in their social interactions. Intermarriage between the two communities was rare, a reflection of the deep-seated cultural and social differences that had developed over time. Additionally, this division was spatially manifested within the village itself. The deep-sea fishermen resided by the sea in an area known as Badugoda, where they had easy access to the ocean. In contrast, the beach seine fishermen lived by the main road, a location that offered them convenient access to the beaches allocated for their fishing practices.

This geographical separation further reinforced the social boundaries between the two groups, creating distinct sections within the village, each with its traditions, practices, and way of life. Understanding this complex social landscape was crucial to my research, as it highlighted the intricate ways technological and economic changes can influence social structures and relationships within a community.

I commenced my research in the beach seine section of the village in the early 1970s. Through a mutual friend, I was introduced to Mr. Nilaweera, a schoolteacher in the village. Mr. Nilaweera played a pivotal role in helping me settle into the community. He assisted me in finding a place to live—an empty house with basic furniture that he kindly provided. Understanding the challenges of living alone in a new environment, Mr. Nilaweera also arranged for an older woman to cook for me. She prepared delicious meals, often including fresh fish caught in the beach seine nets, or embul thiyal using Alagodu maalu which added to the authenticity of my experience.

To further support my research, Mr. Nilaweera introduced me to two key informants—one from the beach seine fishing community, near Mr. Nilaweera’s house, and the other from the deep-sea fishing community in Badugoda. These informants were invaluable to my work; both were highly knowledgeable and willing to share their insights. They patiently answered all my questions, explaining even the minutest details about the village’s social dynamics, fishing practices, and the distinctions between the two communities. Their guidance was instrumental in deepening my understanding of Mirissa’s complex social fabric.

Mr. Gilbert Weerasuriya, the informant from the beach seine community, possessed knowledge far surpassed that of many average villagers. He provided me with a detailed account of how beach seine nets were introduced to the village and traced the history of their evolution. He explained the traditional method of fishing, using these nets, describing how fish were caught by encircling shoals near the shore.

The first nets were made of coir and coconut leaves, which later used hemp thread to make the nets. The madiya, or the deep end of the net where the fish gets caught, is woven with hemp, while the side nets were made with coir lines.

Later in the 1950s nylon was introduced for beach seine nets, and the catch doubled with the new nets. According to him, the beach seine canoe fishermen originally came from the Coromandel Coast, in India, and eventually settled in beach communities, like Negombo and Mirissa, in Sri Lanka. He noted that similar fishing practices can also be found in coastal communities across India. Interestingly, the early beach seiners in these Sri Lankan communities spoke an Indian language, like Telugu, remnants of which were still present in the songs they sing while hauling the seine nets.

My search in the archives revealed that villagers in and around Mirissa had names ending in “Naide,” a corrupted form of an Indian name. In India, particularly in regions like Maharashtra or Karnataka, “Naide” could be a variant or misspelling of the surname “Naidu,” common among Telugu-speaking people. These family names can be found in school thomboos maintained by the Dutch.

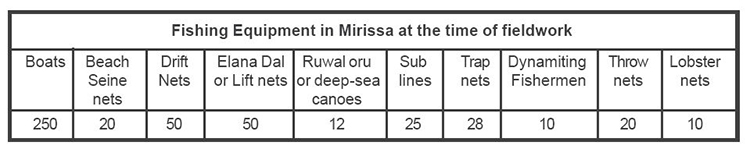

In 1948, at Mirissa, there were only three groups of fishermen: beach seine fishermen, deep sea fishermen, and inshore fishermen. The total number of seine nets in 1947 was 242, owned by a group of 108 fishermen. The deep-sea canoes numbered around 50, operated by about 150 people. Inshore fishing was done in small dugout canoes known as Kuda Oru, with about 20 of them at that time. When I conducted my fieldwork, the numbers had dwindled. There were only six beach seine nets, about 50 deep sea fishermen operated boats and a few Kuda Oru operated by a handful of fishermen.

The process of beach seine fishing involved a large canoe that carried the nets out to sea. The fishermen would then lay the nets in a half-circle, encircling the shoal of fish. Once the nets were in place, the two ends of the circled net were handed over to two groups of fishermen, who began hauling the nets from the shore. At the centre of this operation was the lead fisherman, known as the “mannadirala,” who directed the entire process. The mannadirala would give precise instructions to the hauling groups, ensuring that they drew the net at a specific speed to prevent the fish from escaping through the net. His role was crucial, as the success of the catch depended on the mannalirala’s expertise in coordinating the efforts of the fishermen and controlling the net’s movement.

The beach seine net is owned in shares by various people in the village, and the shoal of fish brought to shore is distributed according to these share ownerships. One-fourth of the catch is allocated to the crew members, known as the “thandukarayo,” (rowers or peddlers) who undertake the challenging task of going out in the canoe to encircle the shoal of fish. Another one-fourth is given to the fishermen responsible for hauling the net at the two ends. A third portion is allocated to the individuals responsible for maintaining the net and the canoe.

The remaining portion is then divided among the shareholders. This division of shares occurs in monetary terms after the fish is sold to vendors and merchants in a process known as “vendesiya.” Additionally, it’s customary for every villager who participated in the fishing activity, even if they are not shareholders, to receive a few fish as a token of appreciation for their contribution. After the fish haul is taken to the shore, people like the mannadirala sort out the fish, separating the big ones from others, like sprats/anchovies or harmless fish. Fish suitable for the family, such as those beneficial for breastfeeding mothers, like kiri boollo, were taken home by the mannadirala and other key individuals.

I was particularly interested in tracing the history of deep-sea canoes, and my interviews with the key informant from the deep-sea fishing community proved invaluable in this regard. This informant, whose knowledge and wisdom were so widely respected that the villagers called him “Soulbury Sami” (Lord Soulbury), was a central figure in the community. Deep-sea fishermen frequently sought his advice on fishing grounds (hantan) and other aspects of deep-sea fishing.

One of the key questions I posed to him was about the number of canoes used for deep-sea fishing before the introduction of mechanized boats. His response was both simple and ingenious. Squatting on the beach, he explained that he could vividly recall who had parked their canoes on his deep-sea canoe’s right and left sides. He took a stick and drew the canoe the family-owned, saying, “This was our oruwa.” Then he drew two similar canoes on each side of his canoe drawn on the beach and said, “I can tell you who owned these two canoes parked beside ours.” He then suggested that I use this method as a starting point. By asking the families who had parked their canoes beside his about their neighbouring canoes, I could piece together a complete picture of the canoe ownership at that time.

This method was remarkably effective. By following his advice and speaking with the families involved, I eventually compiled a list of 48 canoes parked on the beach during the 1940s. This simple yet systematic approach gave me a clear and comprehensive understanding of the deep-sea fishing community’s history before the advent of mechanized boats.

Mirissa has now transformed from a quiet fishing village into a vibrant tourist hub over the past few decades. Once known for its beach seine fishing traditions, the village of Mirissa has evolved significantly over time. The introduction of three-and-a-half-ton boats and trollers modernized its fishing industry, moving the community from traditional fishing methods to more advanced deep-sea fishing. However, over the years, tourism has gradually overtaken fishing as the primary source of livelihood for many villagers. This shift highlights the community’s remarkable adaptability in embracing new opportunities, transforming from a primarily fishing-based economy into a thriving tourist destination.

This small but picturesque destination now boasts over a hundred hotels and boutique accommodations, offering various lodging options for visitors from all over the world. The trajectory of change and transition from being a fishing community focused on beach seine techniques—where nets were dragged ashore by hand—to deep-sea fishing and ultimately to tourism is remarkable. Today, Mirissa is known not for its fishing but for its breathtaking beaches, lush greenery, and panoramic views, making it a must-visit destination in Sri Lanka.

Mirissa’s natural beauty is complemented by an array of activities that attract adventure enthusiasts and nature lovers alike. Whale watching has become one of the village’s most prominent draws, with local boat operators offering tours where visitors can witness the magnificent blue whales, sperm whales, and dolphins in their natural habitat. Additionally, surfing and snorkeling are among the key attractions.

Tourism has brought prosperity to the local community, which depends less on traditional fishing and more on hospitality and tourism services. Many locals earn their livelihoods by operating guesthouses, hotels, and restaurants or by offering services like guided boat tours for whale watching, renting surfboards, and providing transportation for tourists. The once-close connection to the sea, driven by fishing, is now maintained through tourism, as the ocean remains central to the lives of the villagers, albeit in a different way.

Mirissa’s development into a tourist village has not only created economic opportunities. Still, it has also become a cultural melting pot where visitors can experience authentic Sri Lankan traditions, cuisine such as embul thiyal alongside the comforts of modern urban foods. This seamless blend of natural beauty, adventure, and cultural richness makes Mirissa a unique and beloved destination for travellers worldwide.

Features

How Black Civil Rights leaders strengthen democracy in the US

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

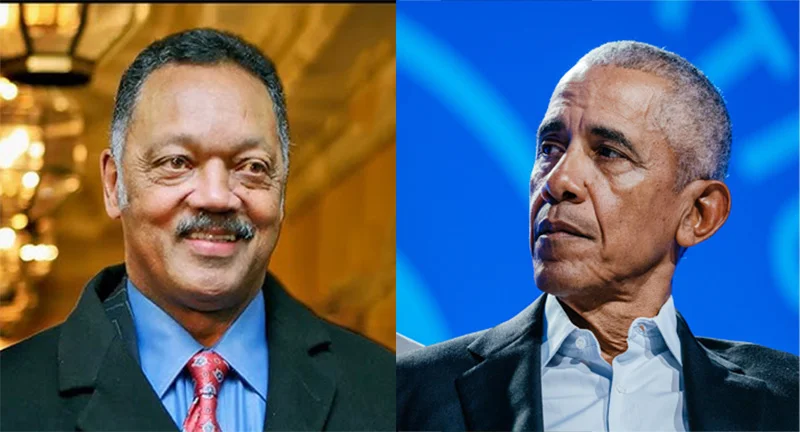

If this were not so, Barack Obama, an Afro-American politician, would never have been elected President of the US. Obama was exceptionally capable, charismatic and eloquent but these qualities alone could not have paved the way for his victory. On careful reflection it could be said that the solid groundwork laid by indefatigable Black Civil Rights activists in the US of the likes of Martin Luther King (Jnr) and Jesse Jackson, who passed away just recently, went a great distance to enable Obama to come to power and that too for two terms. Obama is on record as owning to the profound influence these Civil Rights leaders had on his career.

The fact is that these Civil Rights activists and Obama himself spoke to the hearts and minds of most Americans and convinced them of the need for democratic inclusion in the US. They, in other words, made a convincing case for Black rights. Above all, their struggles were largely peaceful.

Their reasoning resonated well with the thinking sections of the US who saw them as subscribers to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for instance, which made a lucid case for mankind’s equal dignity. That is, ‘all human beings are equal in dignity.’

It may be recalled that Martin Luther King (Jnr.) famously declared: ‘I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed….We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’

Jesse Jackson vied unsuccessfully to be a Democratic Party presidential candidate twice but his energetic campaigns helped to raise public awareness about the injustices and material hardships suffered by the black community in particular. Obama, we now know, worked hard at grass roots level in the run-up to his election. This experience proved invaluable in his efforts to sensitize the public to the harsh realities of the depressed sections of US society.

Cynics are bound to retort on reading the foregoing that all the good work done by the political personalities in question has come to nought in the US; currently administered by Republican hard line President Donald Trump. Needless to say, minority communities are now no longer welcome in the US and migrants are coming to be seen as virtual outcasts who need to be ‘shown the door’ . All this seems to be happening in so short a while since the Democrats were voted out of office at the last presidential election.

However, the last US presidential election was not free of controversy and the lesson is far too easily forgotten that democratic development is a process that needs to be persisted with. In a vital sense it is ‘a journey’ that encounters huge ups and downs. More so why it must be judiciously steered and in the absence of such foresighted managing the democratic process could very well run aground and this misfortune is overtaking the US to a notable extent.

The onus is on the Democratic Party and other sections supportive of democracy to halt the US’ steady slide into authoritarianism and white supremacist rule. They would need to demonstrate the foresight, dexterity and resourcefulness of the Black leaders in focus. In the absence of such dynamic political activism, the steady decline of the US as a major democracy cannot be prevented.

From the foregoing some important foreign policy issues crop-up for the global South in particular. The US’ prowess as the ‘world’s mightiest democracy’ could be called in question at present but none could doubt the flexibility of its governance system. The system’s inclusivity and accommodative nature remains and the possibility could not be ruled out of the system throwing up another leader of the stature of Barack Obama who could to a great extent rally the US public behind him in the direction of democratic development. In the event of the latter happening, the US could come to experience a democratic rejuvenation.

The latter possibilities need to be borne in mind by politicians of the South in particular. The latter have come to inherit a legacy of Non-alignment and this will stand them in good stead; particularly if their countries are bankrupt and helpless, as is Sri Lanka’s lot currently. They cannot afford to take sides rigorously in the foreign relations sphere but Non-alignment should not come to mean for them an unreserved alliance with the major powers of the South, such as China. Nor could they come under the dictates of Russia. For, both these major powers that have been deferentially treated by the South over the decades are essentially authoritarian in nature and a blind tie-up with them would not be in the best interests of the South, going forward.

However, while the South should not ruffle its ties with the big powers of the South it would need to ensure that its ties with the democracies of the West in particular remain intact in a flourishing condition. This is what Non-alignment, correctly understood, advises.

Accordingly, considering the US’ democratic resilience and its intrinsic strengths, the South would do well to be on cordial terms with the US as well. A Black presidency in the US has after all proved that the US is not predestined, so to speak, to be a country for only the jingoistic whites. It could genuinely be an all-inclusive, accommodative democracy and by virtue of these characteristics could be an inspiration for the South.

However, political leaders of the South would need to consider their development options very judiciously. The ‘neo-liberal’ ideology of the West need not necessarily be adopted but central planning and equity could be brought to the forefront of their talks with Western financial institutions. Dexterity in diplomacy would prove vital.

Features

Grown: Rich remnants from two countries

Whispers of Lanka

I was born in a hamlet on the western edge of a tiny teacup bay named Mirissa on the South Coast of Sri Lanka. My childhood was very happy and secure. I played with my cousins and friends on the dusty village roads. We had a few toys to play with, so we always improvised our own games. On rainy days, the village roads became small rivulets on which we sailed paper boats. We could walk from someone’s backyard to another, and there were no fences. We had the freedom to explore the surrounding hills, valleys, and streams.

I was good at school and often helped my classmates with their lessons. I passed the General Certificate of Education (Ordinary Level) at the village school and went to Colombo to study for the General Certificate of Education (Advanced Level). However, I did not like Colombo, and every weekend I hurried back to the village. I was not particularly interested in my studies and struggled in specific subjects. But my teachers knew that I was intelligent and encouraged me to study hard.

To my amazement, I passed the Advanced Level, entered the University of Kelaniya, completed an honours degree in Economics, taught for a few months at a central college, became a lecturer at the same university, and later joined the Department of Census and Statistics as a statistician. Then I went to the University of Wales in the UK to study for an MSc.

The interactions with other international students in my study group, along with very positive recommendations from my professors, helped me secure several jobs in the oil-rich Middle Eastern countries, where I earned salaries unimaginable in Sri Lankan terms. During this period, without much thought, I entered a life focused on material possessions, social status, and excessive consumerism.

Life changes

Unfortunately, this comfortable, enjoyable life changed drastically in the mid-1980s because of the political activities of certain groups. Radicalised youths, brainwashed and empowered by the dynamics of vibrant leftist politics, killed political opponents as well as ordinary people who were reluctant to follow their orders. Their violent methods frightened a large section of Sri Lanka’s middle class into reluctantly accepting country-wide closures of schools, factories, businesses, and government offices.

My father’s generation felt a deep obligation to honour the sacrifices they had made to give us everything we had. There was a belief that you made it in life through your education, and that if you had to work hard, you did. Although I had never seriously considered emigration before, our sons’ education was paramount, and we left Sri Lanka.

Although there were regulations on what could be brought in, migrating to Sydney in the 1980s offered a more relaxed airport experience, with simpler security, a strong presence of airline staff, and a more formal atmosphere. As we were relocating permanently, a few weeks before our departure, we had organised a container to transport sentimental belongings from our home. Our flight baggage was minimal, which puzzled the customs officer, but he laughed when he saw another bulky item on a separate trolley. It was a large box containing a bookshelf purchased in Singapore. Upon discovering that a new migrant family was arriving in Australia with a 32-volume Encyclopaedia Britannica set weighing approximately 250 kilograms, he became cheerful, relaxed his jaw, and said, G’day!

Settling in Sydney

We settled in Epping, Sydney, and enrolled our sons in Epping Boys’ High School. Within one week of our arrival from Sri Lanka, we both found jobs: my wife in her usual accounting position in the private sector, and I was taken on by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). While working at the CAA, I sat the Australian Graduate Admission Test. I secured a graduate position with the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in Canberra, ACT.

We bought a house in Florey, close to my office in Belconnen. The roads near the house were eerily quiet. Back in my hometown of Pelawatta, outside Colombo, my life had a distinct soundtrack. I woke up every morning to the radios blasting ‘pirith’ from the nearby houses; the music of the bread delivery van announcing its arrival, an old man was muttering wild curses to someone while setting up his thambili cart near the junction, free-ranging ‘pariah’ dogs were barking at every moving thing and shadows. Even the wildlife was noisy- black crows gathered on the branches of the mango tree in front of the house to perform a mournful dirge in the morning.

Our Australian neighbours gave us good advice and guidance, and we gradually settled in. If one of the complaints about Asians is that they “won’t join in or integrate to the same degree as Australians do,” this did not apply to us! We never attempted to become Aussies; that was impossible because we didn’t have tanned skin, hazel eyes, or blonde hair, but we did join in the Australian way of life. Having a beer with my next-door neighbour on the weekend and a biannual get-together with the residents of the lane became a routine. Walking or cycling ten kilometres around the Ginninderra Lake with a fit-fanatic of a neighbour was a weekly ritual that I rarely skipped.

Almost every year, early in the New Year, we went to the South Coast. My family and two of our best friends shared a rented house near the beach for a week. There’s not much to do except mix with lots of families with kids, dogs on the beach, lazy days in the sun with a barbecue and a couple of beers in the evening, watching golden sunsets. When you think about Australian summer holidays, that’s all you really need, and that’s all we had!

Caught between two cultures

We tried to hold on to our national tradition of warm hospitality by organising weekend meals with our friends. Enticed by the promise of my wife’s home-cooked feast, our Sri Lankan friends would congregate at our place. Each family would also bring a special dish of food to share. Our house would be crammed with my friends, their spouses and children, the sound of laughter and loud chatter – English mingled with Sinhala – and the aroma of spicy food.

We loved the togetherness, the feeling of never being alone, and the deep sense of belonging within the community. That doesn’t mean I had no regrets in my Australian lifestyle, no matter how trivial they may have seemed. I would have seen migration to another country only as a change of abode and employment, and I would rarely have expected it to bring about far greater changes to my psychological role and identity. In Sri Lanka, I have grown to maturity within a society with rigid demarcation lines between academic, professional, and other groups.

Furthermore, the transplantation from a patriarchal society where family bonds were essential to a culture where individual pursuit of happiness tended to undermine traditional values was a difficult one for me. While I struggled with my changing role, my sons quickly adopted the behaviour and aspirations of their Australian peers. A significant part of our sons’ challenges lay in their being the first generation of Sri Lankan-Australians.

The uniqueness of the responsibilities they discovered while growing up in Australia, and with their parents coming from another country, required them to play a linguistic mediator role, and we, as parents, had to play the cultural mediator role. They were more gregarious and adaptive than we were, and consequently, there was an instant, unrestrained immersion in cultural diversity and plurality.

Technology

They became articulate spokesmen for young Australians growing up in a world where information technology and transactions have become faster, more advanced, and much more widespread. My work in the ABS for nearly twenty years has followed cycles, from data collection, processing, quality assurance, and analysis to mapping, research, and publishing. As the work was mainly computer-based and required assessing and interrogating large datasets, I often had to depend heavily on in-house software developers and mainframe programmers. Over that time, I have worked in several areas of the ABS, making a valuable contribution and gaining a wide range of experience in national accounting.

I immensely valued the unbiased nature of my work, in which the ABS strived to inform its readers without the influence of public opinion or government decisions. It made me proud to work for an organisation that had a high regard for quality, accuracy, and confidentiality. I’m not exaggerating, but it is one of the world’s best statistical organisations! I rubbed shoulders with the greatest statistical minds. The value of this experience was that it enabled me to secure many assignments in Vanuatu, Fiji, East Timor, Saudi Arabia, and the Solomon Islands through the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund after I left the ABS.

Living in Australia

Studying and living in Australia gave my sons ample opportunities to realise that their success depended not on acquiring material wealth but on building human capital. They discovered that it was the sum total of their skills embodied within them: education, intelligence, creativity, work experience and even the ability to play basketball and cricket competitively. They knew it was what they would be left with if someone stripped away all of their assets. So they did their best to pursue their careers on that path and achieve their life goals. Of course, the healthy Australian economy mattered too. As an economist said, “A strong economy did not transform a valet parking attendant into a professor. Investment in human capital did that.”

Nostalgia

After living in Australia for several decades, do I miss Sri Lanka? Which country deserves my preference, the one where I was born or the one to which I migrated? There is no single answer; it depends on opportunities, prospects, lifestyle, and family. Factors such as the cost of living, healthcare, climate, and culture also play significant roles in shaping this preference. Tradition in a slow-motion place like Sri Lanka is an ethical code based on honouring those who do things the same way you do, and dishonour those who don’t. However, in Australia, one has the freedom to express oneself, to debate openly, to hold unconventional views, to be more immune to peer pressure, and not to have one’s every action scrutinised and discussed.

For many years, I have navigated the challenges of cultural differences, conflicting values, and the constant negotiation of where I truly ‘belong.’ Instead of yearning for a ‘dream home’ where I once lived, I have struggled, and to some extent succeeded, to find a home where I live now. This does not mean I have forgotten or discarded my roots. As one Sri Lankan-Australian senior executive remarked, “I have not restricted myself to the box I came in… I was not the ethnicity, skin colour, or lack thereof, of the typical Australian… but that has been irrelevant to my ability to contribute to the things which are important to me and to the country adopted by me.” Now, why do I live where I live – in that old house in Florey? I love the freshness of the air, away from the city smog, noisy traffic, and fumes. I enjoy walking in the evening along the tree-lined avenues and footpaths in my suburb, and occasionally I see a kangaroo hopping along the nature strip. I like the abundance of trees and birds singing at my back door. There are many species of birds in the area, but a common link with ours is the melodious warbling of resident magpies. My wife has been feeding them for several years, and we see the new fledglings every year. At first light and in the evening, they walk up to the back door and sing for their meal. The magpie is an Australian icon, and I think its singing is one of the most melodious sounds in the suburban areas and even more so in the bush.

by Siri Ipalawatte

Features

Big scene for models…

Modelling has turned out to be a big scene here and now there are lots of opportunities for girls and boys to excel as models.

Of course, one can’t step onto the ramp without proper training, and training should be in the hands of those who are aware of what modelling is all about.

Rukmal Senanayake is very much in the news these days and his Model With Ruki – Model Academy & Agency – is responsible for bringing into the limelight, not only upcoming models but also contestants participating in beauty pageants, especially internationally.

On the 29th of January, this year, it was a vibrant scene at the Temple Trees Auditorium, in Colombo, when Rukmal introduced the Grey Goose Road To Future Model Hunt.

Tharaka Gurukanda … in

the scene with Rukmal

This is the second Model Hunt to be held in Sri Lanka; the first was in 2023, at Nelum Pokuna, where over 150 models were able to showcase their skills at one of the largest fashion ramps in Sri Lanka.

The concept was created by Rukmal Senanayake and co-founded by Tharaka Gurukanda.

Future Model Hunt, is the only Southeast Asian fashion show for upcoming models, and designers, to work along and create a career for their future.

The Grey Goose Road To Future Model Hunt, which showcased two segments, brought into the limelight several models, including students of Ruki’s Model Academy & Agency and those who are established as models.

An enthusiastic audience was kept spellbound by the happenings on the ramp.

Doing it differently

Four candidates were also crowned, at this prestigious event, and they will represent Sri Lanka at the respective international pageants.

Those who missed the Grey Goose Road To Future Model Hunt, held last month, can look forward to another exciting Future Model Hunt event, scheduled for the month of May, 2026, where, I’m told, over 150 models will walk the ramp, along with several designers.

It will be held at a prime location in Colombo with an audience count, expected to be over 2000.

Model With Ruki offers training for ramp modelling and beauty pageants and other professional modelling areas.

Their courses cover: Ramp walk techniques, Posture and grooming, Pose and expression, Runway etiquette, and Photo shoots and portfolio building,

They prepare models for local and international fashion events, shoots, and competitions and even send models abroad for various promotional events.

-

Life style4 days ago

Life style4 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features4 days ago

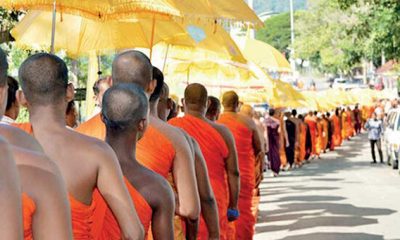

Features4 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoIMF MD here