Features

Sir John becomes PM, the Queen’s visit and the 1956 landslide

(Excerpted from Rendering Unto Caesar, autobiography of Bradman Weerakoon)

(Continued from last week)

The prime minister’s father too had been named John Kotelawela and there was always a whiff of mystery surrounding `John Sr’. There had then been rumours of high intrigue, of family feuds, contract killings and near unassailable alibis. The kavi kola karayas – the wandering minstrels who preceded the radio as purveyors of news in my childhood had sung the story in racy jingles, doubtless embellishing it as time went on. But what was spoken about in whispers was that John Sr had died in prison while awaiting trial after arrest in a foreign land for killing a brother-in-law.

But this could well be the embellishment of an overladen imagination. I would not personally subscribe to its veracity and mention it only to show how the whisper mills grind away in this country. So the son, John Lionel Kotelawela had grown up very much in the care of his dynamic mother Alice. She continued to be a strong influence throughout his life and frequently intervened to help him out of the many sticky situations his reckless tongue got him into.

Alice Kotelawela was one of the three Attygalle sisters of Madapatha who made an important impact on the political history of colonial Ceylon through their dynastic marriages. The eldest, Alice, as we have noted, married John Kotelawela Senior. Leena, the second sister married T F Jayewardene, an uncle of J R Jayewardene, the future president. The youngest, Ellen, married F R Senanayake, the elder brother of D S Senanayake, the first prime minister of independent Ceylon. The Attygalle sisters have been likened to the three Soong sisters of pre-revolutionary China who achieved fame through their marriages to leading political figures.

The Attygalle family network was indeed an impressive one. F R Senanayake’s younger brother D S and D S Senanayake’s son Dudley, were the first and second prime ministers of the country while John Kotelawala’s son Lionel (our Sir John) became the third. These family networks and the way the highest posts rotated among kinsmen led to the UNP being referred to as the ‘Uncle Nephew Party’, a sobriquet not unwarranted by the facts. Political analysts observing this trend being repeated later on in the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), and by contagion in the neighbouring countries as well, were to refer to the phenomenon rather grandly, I think, as dynastic democracy, a typically South Asian variant.

Sir John’s entrance to the office of prime minister on October 12, 1953 was according to him delayed and long over-due. As he perceived it, he should by right and by seniority in the Party, have been appointed by the Governor -General Lord Soulbury to fill the vacancy caused by the death of D S on March 22, 1952. t was a climactic moment in the life of the new nation as D S, like other new leaders who had managed the transition from colony to free state, had been like a father figure.

The question before the leading politicians of the government as D S lay dying – and also the choice being theirs, was, “Who will now be prime minister?” S W R D Bandaranaike, a likely successor, had put himself outside contention by his resignation from the government and the UNP on July 12. 1951, a full eight months before D S’ death. What would have been the country’s future had he continued in the UNP of which he had been a founding member in 1946, and been chosen to succeed? This was to become an often-asked question but I always thought it was irrelevant considering the profound differences in policy and direction between himself and D S.

On crossing the floor’ in a memorable speech he had expressed his frustration at not being able to make the regime implement the progressive reform agenda he had submitted. There was no doubt that after much reflection he had left the government to form his own Party since he was convinced that forces within the UNP would never allow him to succeed D S. With S W R D Bandaranaike out of the way the leading contender was Sir John. He had held ministerial rank since 1936, was now deputy leader, held the portfolio of minister of transport and works and was leader of the house. The other possible candidates were Dudley, D S’s son, and J R Jayewardene who was also a distant relative of the Senanayake’s.

Dudley had been in the Cabinet for less than five years and held the important portfolio of Agriculture and Lands. But he was much younger, relatively inexperienced and had shown no great enthusiasm for the rough and tumble of politics. J R Jayewardene was minister of finance and had earned a reputation as a political strategist but his stand on the language issue – official status for Sinhala – and his penchant for the national dress did not commend him to the old guard of the UNP for the leadership position.

It looked obvious to Sir John and his followers that he would be next in line. But it was not to be. Apparently the late prime minister, since he was in poor health, had advised Lord Soulbury that if anything untoward happened to him he should ask Dudley to form a government. Soulbury was out of the country at the time but had flown back on March 26 and with the minimum of consultation invited Dudley to do so. Dudley was then 41 years old and thus became the youngest prime minister in the Commonwealth.

Lord Soulbury whose appointment to office had been recommended by D S had paid off his debt, but as far as Sir John was concerned he had gained a mortal foe. Indeed Sir John had written a curt letter6 to Soulbury about the breach of British parliamentary convention to which the governor-general had not deigned to respond. It was soon also apparent that a majority of members of the parliamentary group had favoured Dudley over Sir John, who with his characteristic impulsiveness was more than likely to get them all into trouble.

After some days of sulking and denunciation of all the ‘plotters’ from his home at Kandawala Sir John had been persuaded to serve in Dudley’s cabinet, taking up his old portfolio which had been kept vacant. S W R D Bandaranaike watching these goings on from the sidelines was to describe this in his usual pithy terminology as “the culmination of a long, shabby and discreditable intrigue”.’

However, Sir John’s fury at being, as he perceived it, ‘double crossed’ was not to be pacified by ministerial office alone. He had to get it off his chest and he did so in his usual scathing style in a document widely circulated without any authorship, which gave a blow by blow account of how the deed was done. This was the famous The Premier Stakes . As usual his wayward tongue landed him in a heap of trouble. He was in the US on his way to Canada on an official visit when the story broke. Let me record the sequence of the events in his own words. The extract is from his An Asian Prime Minister’s Story.

‘Premier Dudley was prevailed upon to send me this message by cable: “The publication of the The Premier Stakes in 1952 has created a situation which makes it impossible for me to retain you as a member of my Cabinet. I shall, therefore, be glad if you will hand in your resignation by top secret telegram through our Embassy in Washington.”

‘The message was delivered to me with the utmost formality by an official of the Embassy who was very correctly dressed for the occasion, in tails and black tie. His instructions were that I should read it myself. When I had digested the contents of the cabled message which had been sent in code I asked him whether he would send a reply in plain English signed Kotelawala. He said that he certainly would. The reply I dictated made our uneasy diplomat shrink from its emphatic and rudely specific terms. The prime minister was to be asked to thrust the message he sent me into the place where I thought it belonged. Needless to say no reply was sent to Ceylon in these terms through the prescribed channels.’

However, Sir John was advised by many friends to go back to Ceylon and make up with Dudley. Then followed one of those diplomatic denials sometimes euphemistically described as being ‘economical with the truth’ which I was to encounter again and again in my career with top people. It was agreed, as Sir John later wrote, that everything should be forgiven and forgotten. In writing he solemnly asserted that he had nothing to do with the publication of the The Premier Stakes and denied the truth of the statements attributed to him in the document. Dudley accepted the explanation and all was well that ended well.

Blood in the country’s politics has always been thicker than water. Sir John’s mother Alice and Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, who was also an expert at patching up other peoples’ quarrels, then a cabinet minister and later the next governor-general recommended by Sir John, were said to be the prime actors in this charade.

Overlooked in 1952 for the premiership and now more than ever before the heir-apparent, Sir John did not have to wait too long for the prize he was seeking. Dudley as everyone expected called for an early election influenced by two main considerations. One obviously was to take advantage of the considerable sympathy vote following the death of his father. The other was to pre-empt the rising influence of S W R D Bandaranaike, who after the inauguration of the SLFP in September 1951 was seen to be making strong inroads into the traditional rural vote base of the UNP with a highly populist agenda.

But Dudley’s spell of office, after comfortably winning the elections of 1952, was short. Plagued by ill-health and indecisiveness, Dudley resigned on the October 12, 1953, following the widespread hartal (general strike) in August brought about by the government’s abrupt reduction of the subsidized rice ration. Finally Sir John’s perseverance and tenacity had paid off His reputation for being strong-minded and resolute made him the man of the hour within the Party and there was virtually no opposition to his taking over as prime minister.

There were many urgent things to be done; the pre-eminent need being that of getting the strikers off the streets and back to work. There was also the official visit of the Queen which was pending and which Sir John was determined would be an unqualified success.

Sir John, as usual when he undertook a project, took a very personal interest in planning the Queen’s visit. In addition to the customary address to Parliament by the monarch – she was still the nominal head of the government and appointed the governor-general – there was a grand reception at Temple Trees and a special train assembled to take her to Kandy and then on to Polonnaruwa and Anuradhapura, the popular ‘ruined city’ tour.

The massive file on Her Majesty’s visit, which I saw soon after I entered the prime minister’s office, attested to the care and attention which the Railway had paid to the decor of the toilets attached to the Royal carriage and the refurbishment of the master bedroom at the picturesque Polonnaruwa Rest-house on the banks of Parakrama Samudraya tank where the Queen spent one night. For years afterwards locals were wont to make a special effort when staying at Polonnaruwa to ask for the Queen’s bedroom and relate with some awe the experience of having slept in the Queen’s bed.

The visit to Sigiriya was a highlight of the journey. It was breezy at the Lion’s Paw and the young queen had quite a time keeping in place the light cotton dress she had chosen for the hot morning climb. As a sudden gust of wind caused a momentary lifting of the Queen’s dress the irrepressible Sir John shouted “ganing yakko ganing’ to his official photographer Rienzie Wijeratne. The shot was not among the carefully selected album of photographs ceremonially presented to the Royal guest on departure.

A few months after I entered the prime minister’s office, the coming general elections in April of 1956 began to dominate all our work. In February of that decisive year, and more than 14 months earlier than was statutorily necessary, Sir John had advised the governor-general, Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, to dissolve the Parliament. The reason for this was not immediately clear to us.

Ceylon was to celebrate the long awaited 2,500th anniversary of the birth of Gautama Buddha at the full moon (Vesak Poya) in the month of May of 1956. This had been termed Buddha Jayanthi –an event of the highest importance to Buddhists not only in the country but all over the world. Preparations were in hand for the historic occasion and an array of leaders of countries where Buddhism was being practised, including King Mahendra of Nepal were to visit the island on and around the event.

Moreover, Ceylon along with some other countries which had been knocking on the door, had been admitted into the United Nations in December 1955 in a package deal and this was deemed a major diplomatic coup. Past efforts had proved fruitless on account of a continuing Soviet veto. It had been alleged that Ceylon with British bases at Trincomalee and Katunayake was not yet an independent nation. However, these seemingly positive factors notwithstanding, the decision had been taken to go for an early election.

We surmised later that the reason may have been to pre-empt the growing popularity of S W R D Bandaranaike and the formidable coalition, the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna (“MEP”) that he had succeeded in mobilizing. There was also the extraordinary rumour that Dudley Senanayake who had apparently resigned from politics completely, was now thinking of forming a ‘third force’ to contest both Sir John and Bandaranaike, taking away from the UNP some of his former loyalists.

So it was that dissolution of Parliament was fixed for February 18 and after due consultations with the then court astrologer, three days in April just before the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year, auspicious to Sir John – the 5th, 7th and 10th were chosen for the general elections. At the time the practice was to conduct the voting over a few days on the ostensible grounds that elections staffing and security considerations – police at polling booths – would not allow for island-wide elections on a single day.

The real reason, however, was different. Staggered elections were expected to provide for the ‘swing’ to take effect. Government campaign managers usually put up all the strong candidates on the first day so that the voters on the subsequent days could be suitably impressed and influenced by how well the government was doing and would vote accordingly. As it turned out, the results of the first day, April 5 belied all the expectations of Sir John and his advisers.

As caretaker prime minister, Sir John embarked on an elaborate and gruelling 18-hours -a- day programme of meetings and election rallies. The concept of `caretaker’ was taken seriously in those days and as far as possible major policy decisions with large financial implications were postponed. However, in a significant change of policy to counter the ‘Sinhala Only in 24 hours’ slogan of Mr Bandaranaike and his hastily assembled coalition, the UNP leadership too decided to fight the election on the language issue.

The UNP departed from its long held position of parity of status for Sinhala and Tamil as official languages and had adopted the proposal that “Sinhalese alone should be the state language of Ceylon and that immediate action be taken to implement the decision”. The effect of this was that seven Tamil MPs who were UNP members resigned in protest. However, the timing of the change of policy gave the show away and it was perceived by the mass of the electorate as an election stunt. Clearly a case of too little, too late.

Public cynicism had too been growing over the UNP’s alleged misuse of political power. There was a widespread belief that funds were being collected for the Party through the sale of Honours and citizenship rights. Sir John’s impatience with discussion and the image he strove to propagate as a man of action caused irritation.

I personally recalled his peremptory treatment of a body of monks without hearing them out, who had called over at Temple Trees to demand the postponement of the elections. Soon afterwards he threatened to tar-brush the monks who were duseela and took part in politics.

The thoughts of some of us in the prime minister’s office were now turning to the man who was leading the campaign on the other side. The media by and large were hoping for and predicting a UNP victory but there was a low rumble from below that all was not going well with the UNP campaign and that the MEP was gaining ground. Among those who thought so was an American professor of political science whose acquaintance I had made and who seemed confident that Mr Bandaranaike would do very well especially in the rural electorates.

But my feedback to Nadesan and the prime minister was discounted on the grounds that information coming in through police intelligence showed that the UNP was going to win. This total variation between what official intelligence was coming up with – perhaps mostly fulfillment – and the reality on the ground, was something I was to encounter over and over again as I worked with other administrators each time election day, verily the day of reckoning, drew near.

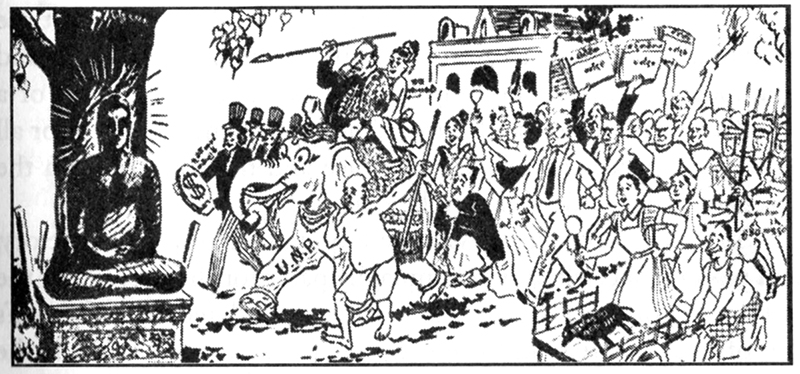

The final nail in Sir John’s coffin was a stunning poster devised by a Bhikku working for the Eksath Bhikku Peramuna (EBP) which was called the “mara yuddhaya.” It depicted Sir John on an elephant (the UNP symbol) at the head of a long parade of girl friends, ballroom dancers, Tamils and champagne drinkers, holding a spear pointed at the heart of a Buddha statue under the Bo tree. The symbolism was plain for all to see. To rescue the religion, the race and the country from the forces of evil, the devil had to be defeated.

Sir John’s supporters, who were quite sure of a UNP victory, had planned a celebratory champagne party for the evening of the last day of polling. Food and drink had been ordered from Victoria’s the official caterers and even the giant flamboyant trees in the beautiful back lawn of Temple Trees, the prime minister’s official residence, were being festooned, as on festive days with myriads of coloured electric bulbs. But as the first night wore on and more and more stalwarts of the UNP bit the dust, Sir John angrily called the ‘victory’ reception off.

Nadesan was quite certain Mr Bandaranaike would not want him to stay on. He had endeared himself to Sir John when the latter was minister of transport in D S Senanayake’s administration and Sir John had brought him in when he himself became prime minister in 1953.

Nadesan was a facile writer and it was reported, had ghost written the An Asian Prime Minister’s Story in addition to compiling an euphoric collection of essays on Sir John entitled ‘This Man Kotelawala’. But what would Mr Bandaranaike do with me? Would it be Siberia for having associated with the enemy? I was ready for anything but I had just got engaged to Damayanthi and our wedding had been planned for August that year.

Features

Rebuilding the country requires consultation

A positive feature of the government that is emerging is its responsiveness to public opinion. The manner in which it has been responding to the furore over the Grade 6 English Reader, in which a weblink to a gay dating site was inserted, has been constructive. Government leaders have taken pains to explain the mishap and reassure everyone concerned that it was not meant to be there and would be removed. They have been meeting religious prelates, educationists and community leaders. In a context where public trust in institutions has been badly eroded over many years, such responsiveness matters. It signals that the government sees itself as accountable to society, including to parents, teachers, and those concerned about the values transmitted through the school system.

This incident also appears to have strengthened unity within the government. The attempt by some opposition politicians and gender misogynists to pin responsibility for this lapse on Prime Minister Dr Harini Amarasuriya, who is also the Minister of Education, has prompted other senior members of the government to come to her defence. This is contrary to speculation that the powerful JVP component of the government is unhappy with the prime minister. More importantly, it demonstrates an understanding within the government that individual ministers should not be scapegoated for systemic shortcomings. Effective governance depends on collective responsibility and solidarity within the leadership, especially during moments of public controversy.

The continuing important role of the prime minister in the government is evident in her meetings with international dignitaries and also in addressing the general public. Last week she chaired the inaugural meeting of the Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka in the aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah. The composition of the task force once again reflects the responsiveness of the government to public opinion. Unlike previous mechanisms set up by governments, which were either all male or without ethnic minority representation, this one includes both, and also includes civil society representation. Decision-making bodies in which there is diversity are more likely to command public legitimacy.

Task Force

The Presidential Task Force to Rebuild Sri Lanka overlooks eight committees to manage different aspects of the recovery, each headed by a sector minister. These committees will focus on Needs Assessment, Restoration of Public Infrastructure, Housing, Local Economies and Livelihoods, Social Infrastructure, Finance and Funding, Data and Information Systems, and Public Communication. This structure appears comprehensive and well designed. However, experience from post-disaster reconstruction in countries such as Indonesia and Sri Lanka after the 2004 tsunami suggests that institutional design alone does not guarantee success. What matters equally is how far these committees engage with those on the ground and remain open to feedback that may complicate, slow down, or even challenge initial plans.

An option that the task force might wish to consider is to develop a linkage with civil society groups with expertise in the areas that the task force is expected to work. The CSO Collective for Emergency Relief has set up several committees that could be linked to the committees supervised by the task force. Such linkages would not weaken the government’s authority but strengthen it by grounding policy in lived realities. Recent findings emphasise the idea of “co-production”, where state and society jointly shape solutions in which sustainable outcomes often emerge when communities are treated not as passive beneficiaries but as partners in problem-solving.

Cyclone Ditwah destroyed more than physical infrastructure. It also destroyed communities. Some were swallowed by landslides and floods, while many others will need to be moved from their homes as they live in areas vulnerable to future disasters. The trauma of displacement is not merely material but social and psychological. Moving communities to new locations requires careful planning. It is not simply a matter of providing people with houses. They need to be relocated to locations and in a manner that permits communities to live together and to have livelihoods. This will require consultation with those who are displaced. Post-disaster evaluations have acknowledged that relocation schemes imposed without community consent often fail, leading to abandonment of new settlements or the emergence of new forms of marginalisation. Even today, abandoned tsunami housing is to be seen in various places that were affected by the 2004 tsunami.

Malaiyaha Tamils

The large-scale reconstruction that needs to take place in parts of the country most severely affected by Cyclone Ditwah also brings an opportunity to deal with the special problems of the Malaiyaha Tamil population. These are people of recent Indian origin who were unjustly treated at the time of Independence and denied rights of citizenship such as land ownership and the vote. This has been a festering problem and a blot on the conscience of the country. The need to resettle people living in those parts of the hill country which are vulnerable to landslides is an opportunity to do justice by the Malaiyaha Tamil community. Technocratic solutions such as high-rise apartments or English-style townhouses that have or are being contemplated may be cost-effective, but may also be culturally inappropriate and socially disruptive. The task is not simply to build houses but to rebuild communities.

The resettlement of people who have lost their homes and communities requires consultation with them. In the same manner, the education reform programme, of which the textbook controversy is only a small part, too needs to be discussed with concerned stakeholders including school teachers and university faculty. Opening up for discussion does not mean giving up one’s own position or values. Rather, it means recognising that better solutions emerge when different perspectives are heard and negotiated. Consultation takes time and can be frustrating, particularly in contexts of crisis where pressure for quick results is intense. However, solutions developed with stakeholder participation are more resilient and less costly in the long run.

Rebuilding after Cyclone Ditwah, addressing historical injustices faced by the Malaiyaha Tamil community, advancing education reform, changing the electoral system to hold provincial elections without further delay and other challenges facing the government, including national reconciliation, all require dialogue across differences and patience with disagreement. Opening up for discussion is not to give up on one’s own position or values, but to listen, to learn, and to arrive at solutions that have wider acceptance. Consultation needs to be treated as an investment in sustainability and legitimacy and not as an obstacle to rapid decisionmaking. Addressing the problems together, especially engagement with affected parties and those who work with them, offers the best chance of rebuilding not only physical infrastructure but also trust between the government and people in the year ahead.

by Jehan Perera

Features

PSTA: Terrorism without terror continues

When the government appointed a committee, led by Rienzie Arsekularatne, Senior President’s Counsel, to draft a new law to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), as promised by the ruling NPP, the writer, in an article published in this journal in July 2025, expressed optimism that, given Arsekularatne’s experience in criminal justice, he would be able to address issues from the perspectives of the State, criminal justice, human rights, suspects, accused, activists, and victims. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), produced by the Committee, has been sharply criticised by individuals and organisations who expected a better outcome that aligns with modern criminal justice and human rights principles.

When the government appointed a committee, led by Rienzie Arsekularatne, Senior President’s Counsel, to draft a new law to replace the Prevention of Terrorism Act (PTA), as promised by the ruling NPP, the writer, in an article published in this journal in July 2025, expressed optimism that, given Arsekularatne’s experience in criminal justice, he would be able to address issues from the perspectives of the State, criminal justice, human rights, suspects, accused, activists, and victims. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), produced by the Committee, has been sharply criticised by individuals and organisations who expected a better outcome that aligns with modern criminal justice and human rights principles.

This article is limited to a discussion of the definition of terrorism. As the writer explained previously, the dangers of an overly broad definition go beyond conviction and increased punishment. Special laws on terrorism allow deviations from standard laws in areas such as preventive detention, arrest, administrative detention, restrictions on judicial decisions regarding bail, lengthy pre-trial detention, the use of confessions, superadded punishments, such as confiscation of property and cancellation of professional licences, banning organisations, and restrictions on publications, among others. The misuse of such laws is not uncommon. Drastic legislation, such as the PTA and emergency regulations, although intended to be used to curb intense violence and deal with emergencies, has been exploited to suppress political opposition.

International Standards

The writer’s basic premise is that, for an act to come within the definition of terrorism, it must either involve “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” or be committed to achieve an objective of an individual or organisation that uses “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” to realise its aims. The UN General Assembly has accepted that the threshold for a possible general offence of terrorism is the provocation of “a state of terror” (Resolution 60/43). The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has taken a similar view, using the phrase “to create a climate of terror.”

In his 2023 report on the implementation of the UN Global Counter-Terrorism Strategy, the Secretary-General warned that vague and overly broad definitions of terrorism in domestic law, often lacking adequate safeguards, violate the principle of legality under international human rights law. He noted that such laws lead to heavy-handed, ineffective, and counterproductive counter-terrorism practices and are frequently misused to target civil society actors and human rights defenders by labelling them as terrorists to obstruct their work.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has stressed in its Handbook on Criminal Justice Responses to Terrorism that definitions of terrorist acts must use precise and unambiguous language, narrowly define punishable conduct and clearly distinguish it from non-punishable behaviour or offences subject to other penalties. The handbook was developed over several months by a team of international experts, including the writer, and was finalised at a workshop in Vienna.

Anti-Terrorism Bill, 2023

A five-member Bench of the Supreme Court that examined the Anti-Terrorism Bill, 2023, agreed with the petitioners that the definition of terrorism in the Bill was too broad and infringed Article 12(1) of the Constitution, and recommended that an exemption (“carve out”) similar to that used in New Zealand under which “the fact that a person engages in any protest, advocacy, or dissent, or engages in any strike, lockout, or other industrial action, is not, by itself, a sufficient basis for inferring that the person” committed the wrongful acts that would otherwise constitute terrorism.

While recognising the Court’s finding that the definition was too broad, the writer argued, in his previous article, that the political, administrative, and law enforcement cultures of the country concerned are crucial factors to consider. Countries such as New Zealand are well ahead of developing nations, where the risk of misuse is higher, and, therefore, definitions should be narrower, with broader and more precise exemptions. How such a “carve out” would play out in practice is uncertain.

In the Supreme Court, it was submitted that for an act to constitute an offence, under a special law on terrorism, there must be terror unleashed in the commission of the act, or it must be carried out in pursuance of the object of an organisation that uses terror to achieve its objectives. In general, only acts that aim at creating “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” should come under the definition of terrorism. There can be terrorism-related acts without violence, for example, when a member of an extremist organisation remotely sabotages an electronic, automated or computerised system in pursuance of the organisation’s goal. But when the same act is committed by, say, a whizz-kid without such a connection, that would be illegal and should be punished, but not under a special law on terrorism. In its determination of the Bill, the Court did not address this submission.

PSTA Proposal

Proposed section 3(1) of the PSTA reads:

Any person who, intentionally or knowingly, commits any act which causes a consequence specified in subsection (2), for the purpose of-

(a) provoking a state of terror;

(b) intimidating the public or any section of the public;

(c) compelling the Government of Sri Lanka, or any other Government, or an international organisation, to do or to abstain from doing any act; or

(d) propagating war, or violating territorial integrity or infringing the sovereignty of Sri Lanka or any other sovereign country, commits the offence of terrorism.

The consequences listed in sub-section (2) include: death; hurt; hostage-taking; abduction or kidnapping; serious damage to any place of public use, any public property, any public or private transportation system or any infrastructure facility or environment; robbery, extortion or theft of public or private property; serious risk to the health and safety of the public or a section of the public; serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with, any electronic or automated or computerised system or network or cyber environment of domains assigned to, or websites registered with such domains assigned to Sri Lanka; destruction of, or serious damage to, religious or cultural property; serious obstruction or damage to, or interference with any electronic, analogue, digital or other wire-linked or wireless transmission system, including signal transmission and any other frequency-based transmission system; without lawful authority, importing, exporting, manufacturing, collecting, obtaining, supplying, trafficking, possessing or using firearms, offensive weapons, ammunition, explosives, articles or things used in the manufacture of explosives or combustible or corrosive substances and biological, chemical, electric, electronic or nuclear weapons, other nuclear explosive devices, nuclear material, radioactive substances, or radiation-emitting devices.

Under section 3(5), “any person who commits an act which constitutes an offence under the nine international treaties on terrorism, ratified by Sri Lanka, also commits the offence of terrorism.” No one would contest that.

The New Zealand “carve-out” is found in sub-section (4): “The fact that a person engages in any protest, advocacy or dissent or engages in any strike, lockout or other industrial action, is not by itself a sufficient basis for inferring that such person (a) commits or attempts, abets, conspires, or prepares to commit the act with the intention or knowledge specified in subsection (1); or (b) is intending to cause or knowingly causes an outcome specified in subsection (2).”

While the Arsekularatne Committee has proposed, including the New Zealand “carve out”, it has ignored a crucial qualification in section 5(2) of that country’s Terrorism Suppression Act, that for an act to be considered a terrorist act, it must be carried out for one or more purposes that are or include advancing “an ideological, political, or religious cause”, with the intention of either intimidating a population or coercing or forcing a government or an international organisation to do or abstain from doing any act.

When the Committee was appointed, the Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka opined that any new offence with respect to “terrorism” should contain a specific and narrow definition of terrorism, such as the following: “Any person who by the use of force or violence unlawfully targets the civilian population or a segment of the civilian population with the intent to spread fear among such population or segment thereof in furtherance of a political, ideological, or religious cause commits the offence of terrorism”.

The writer submits that, rather than bringing in the requirement of “a political, ideological, or religious cause”, it would be prudent to qualify proposed section 3(1) by the requirement that only acts that aim at creating “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” or are carried out to achieve a goal of an individual or organisation that employs “terror” or a “state of intense or overwhelming fear” to attain its objectives should come under the definition of terrorism. Such a threshold is recognised internationally; no “carve out” is then needed, and the concerns of the Human Rights Commission would also be addressed.

by Dr. Jayampathy Wickramaratne

President’s Counsel

Features

ROCK meets REGGAE 2026

We generally have in our midst the famous JAYASRI twins, Rohitha and Rohan, who are based in Austria but make it a point to entertain their fans in Sri Lanka on a regular basis.

We generally have in our midst the famous JAYASRI twins, Rohitha and Rohan, who are based in Austria but make it a point to entertain their fans in Sri Lanka on a regular basis.

Well, rock and reggae fans get ready for a major happening on 28th February (Oops, a special day where I’m concerned!) as the much-awaited ROCK meets REGGAE event booms into action at the Nelum Pokuna outdoor theatre.

It was seven years ago, in 2019, that the last ROCK meets REGGAE concert was held in Colombo, and then the Covid scene cropped up.

Chitral Somapala with BLACK MAJESTY

This year’s event will feature our rock star Chitral Somapala with the Australian Rock+Metal band BLACK MAJESTY, and the reggae twins Rohitha and Rohan Jayalath with the original JAYASRI – the full band, with seven members from Vienna, Austria.

According to Rohitha, the JAYASRI outfit is enthusiastically looking forward to entertaining music lovers here with their brand of music.

Their playlist for 28th February will consist of the songs they do at festivals in Europe, as well as originals, and also English and Sinhala hits, and selected covers.

Says Rohitha: “We have put up a great team, here in Sri Lanka, to give this event an international setting and maintain high standards, and this will be a great experience for our Sri Lankan music lovers … not only for Rock and Reggae fans. Yes, there will be some opening acts, and many surprises, as well.”

Rohitha, Chitral and Rohan: Big scene at ROCK meets REGGAE

Rohitha and Rohan also conveyed their love and festive blessings to everyone in Sri Lanka, stating “This Christmas was different as our country faced a catastrophic situation and, indeed, it’s a great time to help and share the real love of Jesus Christ by helping the poor, the needy and the homeless people. Let’s RISE UP as a great nation in 2026.”

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

News2 days ago

News2 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II