Features

WAKE UP SRI LANKA ……Presidential Elections 2024

by Mohan Mendis

The 2019 and 2024 Sri Lankan presidential elections saw significant shifts in political leadership and voter preferences.

In 2019, Gotabaya Rajapaksa, representing the Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna (SLPP), won with 52.25% of the vote, defeating Sajith Premadasa of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), who garnered 41.99%. Rajapaksa’s victory was driven by promises of strong governance, national security, and economic stability, but his administration faced severe challenges due to the economic crisis that led to his resignation in 2022.

In 2024, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, leader of the Marxist National People’s Power (NPP), emerged as the victor with 42.31% of the vote, surpassing Premadasa, who secured 32.76%. Dissanayake’s victory reflected widespread public dissatisfaction with the traditional political elite, as he campaigned on a platform of anti-corruption and working-class representation. His win signaled a major political shift, particularly in light of the country’s ongoing economic recovery following the 2022 crisis. While Dissanayake did not secure an outright majority, he won after a second round of vote redistribution, marking a historic moment in Sri Lanka’s politics, as he represented a break from the dominance of traditional political families like the Rajapaksas and Premadasa.

Here’s a statistical comparison between the 2019 and 2024 Sri Lankan

presidential election results:

2019 Presidential Election Results:

Winner: Gotabaya Rajapaksa (Sri Lanka Podujana Peramuna – SLPP)

Votes: 6,924,255

Percentage: 52.25%

Runner-up: Sajith Premadasa (Samagi Jana Balawegaya – SJB)

Votes: 5,564,239

Percentage: 41.99%

Voter Turnout: 83.72%

2024 Presidential Election Results:

Winner: Anura Kumara Dissanayake (National People’s Power – NPP)

Votes: 5,740,179

Percentage: 42.31%

• Runner-up: Sajith Premadasa (SJB)

Votes: 4,530,902

Percentage: 32.76%

Voter Turnout: 76%

Key Differences:

1. Winning Margin:

= 2019: Rajapaksa won by a margin of 10.26%.

= 2024: Dissanayake won with 9.55% fewer votes than Rajapaksa did in 2019, and his margin over Premadasa was 9.55%.

2. Performance of Sajith Premadasa:

= 2019: Premadasa received 41.99% of the vote.

= 2024: Premadasa’s vote share dropped to 32.76%, a decrease of

9.23%.

3. Turnout:

2019: Turnout was higher at 83.72%.

2024: Turnout fell to 76%, indicating slightly lower voter participation This comparison reflects a shift from the dominance of traditional political figures to a more left-wing, anti-establishment candidate in 2024.

If Sajith Premadasa and Ranil Wickremesinghe had contested together in the 2024

Sri Lankan presidential election, their combined vote total could have significantly altered the outcome.

Premadasa’s 2024 vote share: 4,530,902 votes (32.76%)

Wickremesinghe’s 2024 estimated vote share: Although Wickremesinghe ran as an independent in 2024, his support base would primarily come from his long-time affiliation with the United National Party (UNP). Given his recent governance, we can estimate his vote base to be around 8-10%, based on the fragmented political landscape after the 2022 economic crisis

Combined Vote Estimate:

If we add an estimated 8-10% support for Wickremesinghe to Premadasa’s 32.76%, their combined vote share could have reached:

Around 40-43% of the total vote, with around 6-6.5 million votes.

This combination would likely have outperformed Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s 42.31% (5,740,179 votes), potentially leading to a victory for the combined opposition. However, this scenario depends on various factors:

Voter behavior: Not all of Wickremesinghe’s supporters might have automatically backed a Premadasa-Wickremesinghe alliance.

Strategic alignment: Wickremesinghe’s pro-market policies and Premadasa’s more populist stances may not fully align, possibly affecting voter turnout and support.

In conclusion, a joint candidacy could have statistically won the election, but the actual dynamics would depend on the coherence of their combined platform and voter perception.

The 2024 Sri Lankan presidential election saw a drop in voter turnout, an increase in the number of rejected votes, and a larger voter base due to demographic changes compared to 2019. Let’s break down these elements:

1. Voter Turnout:

2019: Voter turnout was 83.72%, reflecting high engagement during a time when national security and economic concerns were dominant.

2024: Turnout dropped to 76%, which is a significant decline

Factors Contributing to the Drop in Turnout:

Disillusionment with traditional political parties: Voters became frustrated with the old political guard due to their perceived role in Sri Lanka’s economic collapse. This disenchantment likely discouraged voter participation, especially for Ranil Wickremesinghe and Sajith Premadasa, whose parties were part of the “establishment.”

Economic instability and voter fatigue: After a severe economic crisis in 2022, many citizens felt the political process did not adequately address their concerns, further lowering voter enthusiasm.

Frustration with political elites: The dissatisfaction with traditional political families (such as the Rajapaksas and the Wickremesinghe-led UNP) led many voters to feel their votes wouldn’t significantly change the status quo

Reduced enthusiasm: After the crisis in 2022, many voters were struggling with day-to-day survival, leading to a decreased interest in political participation.

Large-Scale Emigration Since 2022: Following the 2022 economic collapse, an estimated 500,000 to 700,000 Sri Lankans left the country. Many were professionals, skilled workers, and members of the middle class, who were seeking better economic opportunities abroad due to the high inflation, shortages of basic goods, and the general economic instability in Sri Lanka

Loss of eligible voters: A significant portion of those who left were eligible voters. Since Sri Lanka does not have an established mechanism for absentee voting for citizens living abroad, these individuals were effectively excluded from the 2024 election process.

2. Impact of Economic Migration on Voter Motivation:

Frustration and disengagement: Many who remained in Sri Lanka may have felt disillusioned by the lack of effective governance, leading to voter apathy.

The exodus likely signaled a deep disconnection between citizens and the political system, as those who left may have represented a politically active demographic.

• Diaspora influence: While Sri Lankans living abroad typically maintain strong ties with their homeland, their inability to vote could have dampened political enthusiasm among their families and networks at home. This may have further contributed to the sense of futility in voting, reducing turnout.

3. Economic Hardships and Focus on Survival:

= Those remaining in the country continued to struggle with the aftermath of the economic collapse, including high taxes, inflation, and daily hardships. For many, political engagement took a backseat to focusing on economic survival. When citizens are burdened with meeting basic needs, voter participation can decline as political engagement becomes less of a priority

4. Lower Middle-Class and Professional Exodus:

The people who left were often from urban, educated, and professional backgrounds, a group that traditionally had higher political engagement.

Their absence directly impacted turnout, as many who typically participate in elections had left the country. This reduction was compounded by the youth and first-time voters who supported Anura Kumara Dissanayake, balancing the overall turnout to an extent, but not fully compensating for the exodus.

5. Lack of Trust in the Political System:

With Ranil Wickremesinghe taking over after the 2022 crisis and enacting austerity measures, many citizens felt betrayed by both the government and the opposition. The traditional political parties failed to regain trust, and this disillusionment likely led to a sense of hopelessness among voters, reducing their participation further. The combination of large-scale migration, disenchantment with the political system, and economic hardships all contributed to the reduced voter turnout in 2024. The lack of absentee voting rights for Sri Lankans abroad compounded the issue, as many potential voters were unable to participate in the electoral process, contributing to the overall decline in turnout

LESSONS LEARNT TO BE LEARNT BY ALL THREE MAJOR CANDIDATES BASED ON THE ELECTION VOTES

Based on the 2024 Sri Lankan presidential election results, each of the three major candidates — Anura Kumara Dissanayake, Sajith Premadasa, and Ranil Wickremesinghe — can draw important lessons to improve their future political strategies:

1. Anura Kumara Dissanayake (NPP):

= Key Lesson: Sustain Popular Momentum with Broader Appeal

Victory and Support from Youth and Left-Wing Voters: Dissanayake’s victory in 2024 reflected his success in capturing the youth vote, as well as those frustrated with traditional political elites. His anti-corruption and antiestablishment stance appealed to many who wanted change after the economic crisis

Challenge

: He must now expand his appeal beyond his core base. Though his 42.31% vote share brought him victory, it wasn’t an outright majority. His Marxist platform and revolutionary background make financial and business circles wary, which could hamper economic reforms and stability Lesson: To secure broader support, Dissanayake will need to moderate his economic policies to reassure businesses while staying true to his progressive base. He must also deliver on promises of systemic change, which was key to his support among younger voters.

2. Sajith Premadasa (SJB):

= Key Lesson: Reinvent Campaign Strategy and Unite the Opposition Failure to Build Momentum: Despite his 32.76% vote share, Premadasa failed to capitalize on the public’s discontent with traditional politics. His drop in support from the 41.99% in 2019 reveals that he could not gain the trust of those seeking change Challenge: Premadasa’s policies may not have stood out enough to differentiate him from the very system voters were rejecting. His inability to consolidate the opposition vote, especially in the face of Ranil Wickremesinghe’s split candidacy, further diminished his chances of winning. Lesson: Premadasa needs to reform his image and policy platform to offer a clear alternative to the status quo. Additionally, building alliances and uniting fragmented opposition forces, including Wickremesinghe’s supporters, would increase his chances in future elections.

3. Ranil Wickremesinghe (UNP):

Key Lesson: Address Public Discontent and Reform Political Strategy Economic Stabilization but Political Defeat: Wickremesinghe’s focus on economic recovery, including debt restructuring with the IMF, may have stabilized inflation and foreign reserves, but his low voter support (estimated 8-10%) showed a significant disconnect with the electorate).

His austerity measures were unpopular, as they were perceived as benefiting the elite while burdening ordinary citizens with higher taxes and costs. Challenge: Wickremesinghe’s political brand has become synonymous with the establishment, which is seen as partly responsible for the country’s crises. This made it difficult for him to attract a broad voter base despite his economic reforms.

Lesson

: He needs to rebuild public trust, particularly by demonstrating empathy for ordinary citizens affected by austerity measures. Engaging in more transparent governance and incorporating social welfare policies into economic recovery plans could help him regain public favor.

Additional Lessons for All Candidates:

Address Voter Disenchantment: The 7.72% drop in voter turnout and rise in rejected votes signal widespread disillusionment. All candidates must focus on rebuilding trust in democratic institutions by addressing the public’s core concerns, especially economic hardships and corruption

Incorporate the Diaspora: Given the significant exodus of Sri Lankans overseas, candidates should advocate for mechanisms such as absentee voting to engage the diaspora, many of whom still hold strong ties to the country and could be influential voters.

Offer Clear Policy Alternatives: The growing complexity of voter issues, particularly in the post-crisis landscape, requires candidates to offer clear, actionable policy proposals that address both short-term survival (inflation, employment) and long-term reforms (corruption, education, economic diversification).

These lessons highlight the importance of trust, clarity of message, and broad-based coalitions in an evolving political environment marked by economic uncertainty and widespread public dissatisfaction.

If Sajith Premadasa and Ranil Wickremesinghe had contested together in the 2024

Sri Lankan presidential election, their combined vote total could have significantly altered the outcome.

Potential Combined Vote Share (Premadasa + Wickremesinghe):

Premadasa’s 2024 vote share: 4,530,902 votes (32.76%)

Wickremesinghe’s 2024 estimated vote share: Although Wickremesinghe ran as an independent in 2024, his support base would primarily come from his long-time affiliation with the United National Party (UNP). Given his recent governance, we can estimate his vote base to be around 8-10%, based on the fragmented political landscape after the 2022 economic crisis

Combined Vote Estimate:

If we add an estimated 8-10% support for Wickremesinghe to Premadasa’s 32.76%, their combined vote share could have reached:

Around 40-43% of the total vote, with around 6-6.5 million votes. This combination would likely have outperformed Anura Kumara Dissanayake’s 42.31% (5,740,179 votes), potentially leading to a victory for the combined opposition. However, this scenario depends on various factors:

Voter behavior: Not all of Wickremesinghe’s supporters might have automatically backed a Premadasa-Wickremesinghe alliance.

Strategic alignment: Wickremesinghe’s pro-market policies and Premadasa’s more populist stances may not fully align, possibly affecting voter turnout and support. In conclusion, a joint candidacy could have statistically won the election, but the actual dynamics would depend on the coherence of their combined platform and voter perception.

The United National Party (UNP) and the Samagi Jana Balawegaya (SJB), despite their shared origins, remain divided as a united political force for several key reasons:

1. Leadership Rift between Ranil Wickremesinghe and Sajith Premadasa:

The primary reason for the division is the personal and leadership rivalry between Ranil Wickremesinghe, the long-time leader of the UNP, and Sajith Premadasa, who broke away to form the SJB in 2020.

Premadasa’s frustration: Premadasa had long sought a leadership role within the UNP, but Wickremesinghe’s reluctance to step down or share power with younger leaders created tension within the party. This frustration culminated in Premadasa forming the SJB ahead of the 2020 parliamentary elections .

Wickremesinghe’s dominance: Wickremesinghe’s control over the UNP and his reluctance to pass the torch exacerbated internal tensions. Many UNP members felt that under Wickremesinghe, the party was becoming disconnected from voters, but they couldn’t reform leadership, leading to the SJB split

2. Ideological and Policy Differences:

While both parties have roots in the UNP’s center-right liberalism, the SJB has taken a more populist and centrist approach under Premadasa. The SJB focuses on social welfare programs and expanding public services, making it more appealing to working-class voters.

UNP’s pro-market policies: Under Wickremesinghe, the UNP continued to champion pro-market, neoliberal economic policies, favoring privatization, foreign investments, and austerity measures. These policies became particularly unpopular after the 2022 economic crisis, further alienating a segment of voters who felt left behind

The SJB’s attempt to distance itself from these neoliberal policies was a critical reason for Premadasa’s breakaway and remains a central division between the two parties.

3. Public Perception of the Parties:

The UNP’s popularity sharply declined after the 2019 presidential election, where Wickremesinghe’s leadership was seen as ineffective in addressing key national issues, including the Easter Sunday attacks and the economic downturn. The party’s inability to stop the rise of the Rajapaksas was also a sore point for many supporters.

SJB’s formation was seen as a fresh start and an opportunity for renewal. Premadasa’s SJB quickly gained traction as a stronger opposition force against the Rajapaksas, winning more seats than the UNP in the 2020 parliamentary elections .

Public distrust of the UNP after the 2022 crisis, where Wickremesinghe was appointed president following Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s resignation, has reinforced the perception of the UNP as part of the old political guard that failed to protect the country from economic collapse.

4. Strategic Differences:

Premadasa’s SJB has focused on grassroots mobilization and appealing to the general public’s frustration with the status quo. His campaign style is more people-centric, offering populist measures that address immediate economic concerns.

Wickremesinghe’s UNP, in contrast, relies on institutional experience and positioning itself as the party with the capability to manage macroeconomic issues, especially in navigating complex financial negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF). However, these strategies have not resonated with the broader electorate, which is looking for immediate relief.

5. Electoral Competition and Political Ambitions:

Both Premadasa and Wickremesinghe harbor strong political ambitions. Premadasa, as the leader of the SJB, sees himself as the face of Sri Lanka’s opposition, while Wickremesinghe continues to hold the presidency and remains determined to maintain his political relevance.

Competition for leadership: A merger between the two parties would likely force a power-sharing agreement, something neither leader seems willing to compromise on. This leadership struggle and competition for dominance in the opposition landscape make a merger highly unlikely without significant concessions

6. Party Structures and Grassroots Support:

The SJB’s infrastructure and voter base have been growing rapidly since its formation, attracting disillusioned former UNP members and voters, particularly from rural areas. On the other hand, the UNP’s support base has dwindled, particularly after its near-total defeat in the 2020 parliamentary elections, where it won just one seat.

This asymmetry in organizational strength and grassroots support makes it difficult for both parties to merge, as the SJB now commands the larger voter base and structure, while the UNP relies on its institutional history and Wickremesinghe’s position as president.

Conclusion:

The rivalry between Premadasa and Wickremesinghe, combined with policy differences, strategic ambitions, and diverging party infrastructures, makes it difficult for the UNP and SJB to unite as a political force. While they share a common origin, their leadership conflicts and differing visions for the country’s future have created significant barriers to reconciliation and unity in Sri Lankan politics. For the people of Sri Lanka striving for a new beginning—focused on prosperity, corruption-free governance, the rule of law, and unity among diverse communities—the following guiding lessons are crucial:

1. Strong Rule of Law and Accountability:

To ensure a corruption-free society, it is vital that Sri Lanka strengthens its legal and institutional frameworks:

• Transparent governance: Implement transparency in government contracts, spending, and policies. This includes creating robust mechanisms to audit public officials, ensuring that corruption and mismanagement are detected and addressed.

• Independent judiciary: Strengthening the judiciary so that it is free from political influence will restore faith in legal systems. Citizens must trust that laws will be applied equally, regardless of political or social status.

• Anti-corruption institutions: Fully empower institutions such as the Commission to Investigate Allegations of Bribery or Corruption (CIABOC), giving them the resources and independence to investigate and prosecute corruption effectively

2. Inclusive Economic Development:

For Sri Lanka to achieve sustainable prosperity, it is crucial that economic growth is inclusive and benefits all regions, ethnicities, and social classes:

• Equitable growth: Economic policies must focus on bridging the urban-rural divide and ensure equitable access to opportunities. Special emphasis should be placed on regions affected by the civil war, such as the North and East, where communities continue to struggle with poverty and infrastructure deficits.

• Investment in education and skills: The country’s future prosperity depends on education reform and equipping youth with modern skills for global markets. Investments in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education can boost innovation and create more job opportunities.

• Support for small businesses and entrepreneurs: Encourage local entrepreneurship through microfinance programs, innovation hubs, and support for agriculture and tourism industries, which have the potential to uplift rural economies

3. Strengthening Democracy and Civic Engagement:

The 2022 mass protests, where people demanded government accountability, show a shift towards active civic engagement. To maintain momentum:

• Participatory governance: Citizens should be encouraged to engage in local decision-making processes. Decentralization of government functions can bring decision-making closer to the people, ensuring their voices are heard.

• Civic education: Programs that educate citizens, particularly the youth, on democratic values and their role in governance can foster a politically conscious population that holds leaders accountable.

• Reform political institutions: There must be significant reforms in electoral laws to reduce the influence of money and political dynasties. Ensuring that elections are free, fair, and competitive is critical for democracy to flourish

4. Promoting National Unity Across Ethnic and Religious Lines:

Sri Lanka’s diverse ethnic and religious fabric has historically been both its strength and a source of conflict. Building a unified nation requires a genuine commitment to:

• Reconciliation and healing: Post-civil war reconciliation must move beyond superficial initiatives. Policies that address the grievances of Tamil, Muslim, and other minority communities should focus on restoring cultural autonomy and rebuilding trust through transitional justice processes that include reparations, truth-telling, and recognition of past wrongs.

• Inclusive leadership: Leaders must work to break down ethnic and religious divides. National discourse should celebrate diversity and encourage interfaith dialogue to foster mutual understanding.

• Balanced development: Ensure that all regions and communities, regardless of ethnic makeup, receive equal access to resources, infrastructure, and education. This creates a shared sense of belonging and reduces regional disparities

5. Building Trust through Transparent Economic Recovery:

Given the economic crisis of 2022, public trust in governance has eroded:

• Debt transparency: Sri Lanka must adopt clear and transparent debt management policies, allowing citizens to understand how foreign loans and aid are utilized. Public access to information about IMF and other foreign assistance programs will help reduce skepticism.

• Fair tax policies: Implement tax reforms that do not overly burden the working class but ensure the wealthy contribute fairly to economic recovery. Equitable tax policies can foster trust that recovery efforts are being handled responsibly

6. Sustainable and Environmentally-Conscious Policies:

• Environmental stewardship: Protecting Sri Lanka’s natural resources is crucial for long-term prosperity. Policies should promote sustainable development that balances economic growth with environmental preservation, particularly in industries like tourism and agriculture.

• Disaster preparedness: As a nation vulnerable to climate change, Sri Lanka must prioritize disaster resilience through investments in infrastructure, water management, and sustainable agriculture practices

7. Ending Political Dynasties and Cronyism:

One of the most pressing issues in Sri Lanka’s politics has been the dominance of political families (e.g., Rajapaksas), which has led to allegations of corruption and cronyism:

Features

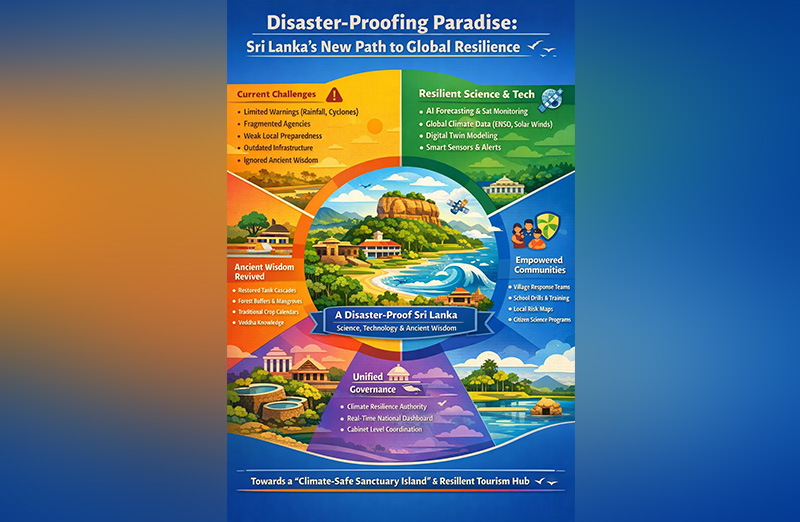

Disaster-proofing paradise: Sri Lanka’s new path to global resilience

iyadasa Advisor to the Ministry of Science & Technology and a Board of Directors of Sri Lanka Atomic Energy Regulatory Council A value chain management consultant to www.vivonta.lk

As climate shocks multiply worldwide from unseasonal droughts and flash floods to cyclones that now carry unpredictable fury Sri Lanka, long known for its lush biodiversity and heritage, stands at a crossroads. We can either remain locked in a reactive cycle of warnings and recovery, or boldly transform into the world’s first disaster-proof tropical nation — a secure haven for citizens and a trusted destination for global travelers.

The Presidential declaration to transition within one year from a limited, rainfall-and-cyclone-dependent warning system to a full-spectrum, science-enabled resilience model is not only historic — it’s urgent. This policy shift marks the beginning of a new era: one where nature, technology, ancient wisdom, and community preparedness work in harmony to protect every Sri Lankan village and every visiting tourist.

The Current System’s Fatal Gaps

Today, Sri Lanka’s disaster management system is dangerously underpowered for the accelerating climate era. Our primary reliance is on monsoon rainfall tracking and cyclone alerts — helpful, but inadequate in the face of multi-hazard threats such as flash floods, landslides, droughts, lightning storms, and urban inundation.

Institutions are fragmented; responsibilities crisscross between agencies, often with unclear mandates and slow decision cycles. Community-level preparedness is minimal — nearly half of households lack basic knowledge on what to do when a disaster strikes. Infrastructure in key regions is outdated, with urban drains, tank sluices, and bunds built for rainfall patterns of the 1960s, not today’s intense cloudbursts or sea-level rise.

Critically, Sri Lanka is not yet integrated with global planetary systems — solar winds, El Niño cycles, Indian Ocean Dipole shifts — despite clear evidence that these invisible climate forces shape our rainfall, storm intensity, and drought rhythms. Worse, we have lost touch with our ancestral systems of environmental management — from tank cascades to forest sanctuaries — that sustained this island for over two millennia.

This system, in short, is outdated, siloed, and reactive. And it must change.

A New Vision for Disaster-Proof Sri Lanka

Under the new policy shift, Sri Lanka will adopt a complete resilience architecture that transforms climate disaster prevention into a national development strategy. This system rests on five interlinked pillars:

Science and Predictive Intelligence

We will move beyond surface-level forecasting. A new national climate intelligence platform will integrate:

AI-driven pattern recognition of rainfall and flood events

Global data from solar activity, ocean oscillations (ENSO, MJO, IOD)

High-resolution digital twins of floodplains and cities

Real-time satellite feeds on cyclone trajectory and ocean heat

The adverse impacts of global warming—such as sea-level rise, the proliferation of pests and diseases affecting human health and food production, and the change of functionality of chlorophyll—must be systematically captured, rigorously analysed, and addressed through proactive, advance decision-making.

This fusion of local and global data will allow days to weeks of anticipatory action, rather than hours of late alerts.

Advanced Technology and Early Warning Infrastructure

Cell-broadcast alerts in all three national languages, expanded weather radar, flood-sensing drones, and tsunami-resilient siren networks will be deployed. Community-level sensors in key river basins and tanks will monitor and report in real-time. Infrastructure projects will now embed climate-risk metrics — from cyclone-proof buildings to sea-level-ready roads.

Governance Overhaul

A new centralised authority — Sri Lanka Climate & Earth Systems Resilience Authority — will consolidate environmental, meteorological, Geological, hydrological, and disaster functions. It will report directly to the Cabinet with a real-time national dashboard. District Disaster Units will be upgraded with GN-level digital coordination. Climate literacy will be declared a national priority.

People Power and Community Preparedness

We will train 25,000 village-level disaster wardens and first responders. Schools will run annual drills for floods, cyclones, tsunamis and landslides. Every community will map its local hazard zones and co-create its own resilience plan. A national climate citizenship programme will reward youth and civil organisations contributing to early warning systems, reforestation (riverbank, slopy land and catchment areas) , or tech solutions.

Reviving Ancient Ecological Wisdom

Sri Lanka’s ancestors engineered tank cascades that regulated floods, stored water, and cooled microclimates. Forest belts protected valleys; sacred groves were biodiversity reservoirs. This policy revives those systems:

Restoring 10,000 hectares of tank ecosystems

Conserving coastal mangroves and reintroducing stone spillways

Integrating traditional seasonal calendars with AI forecasts

Recognising Vedda knowledge of climate shifts as part of national risk strategy

Our past and future must align, or both will be lost.

A Global Destination for Resilient Tourism

Climate-conscious travelers increasingly seek safe, secure, and sustainable destinations. Under this policy, Sri Lanka will position itself as the world’s first “climate-safe sanctuary island” — a place where:

Resorts are cyclone- and tsunami-resilient

Tourists receive live hazard updates via mobile apps

World Heritage Sites are protected by environmental buffers

Visitors can witness tank restoration, ancient climate engineering, and modern AI in action

Sri Lanka will invite scientists, startups, and resilience investors to join our innovation ecosystem — building eco-tourism that’s disaster-proof by design.

Resilience as a National Identity

This shift is not just about floods or cyclones. It is about redefining our identity. To be Sri Lankan must mean to live in harmony with nature and to be ready for its changes. Our ancestors did it. The science now supports it. The time has come.

Let us turn Sri Lanka into the world’s first climate-resilient heritage island — where ancient wisdom meets cutting-edge science, and every citizen stands protected under one shield: a disaster-proof nation.

Features

The minstrel monk and Rafiki the old mandrill in The Lion King – I

Why is national identity so important for a people? AI provides us with an answer worth understanding critically (Caveat: Even AI wisdom should be subjected to the Buddha’s advice to the young Kalamas):

‘A strong sense of identity is crucial for a people as it fosters belonging, builds self-worth, guides behaviour, and provides resilience, allowing individuals to feel connected, make meaningful choices aligned with their values, and maintain mental well-being even amidst societal changes or challenges, acting as a foundation for individual and collective strength. It defines “who we are” culturally and personally, driving shared narratives, pride, political action, and healthier relationships by grounding people in common values, traditions, and a sense of purpose.’

Ethnic Sinhalese who form about 75% of the Sri Lankan population have such a unique identity secured by the binding medium of their Buddhist faith. It is significant that 93% of them still remain Buddhist (according to 2024 statistics/wikipedia), professing Theravada Buddhism, after four and a half centuries of coercive Christianising European occupation that ended in 1948. The Sinhalese are a unique ancient island people with a 2500 year long recorded history, their own language and country, and their deeply evolved Buddhist cultural identity.

Buddhism can be defined, rather paradoxically, as a non-religious religion, an eminently practical ethical-philosophy based on mind cultivation, wisdom and universal compassion. It is an ethico-spiritual value system that prioritises human reason and unaided (i.e., unassisted by any divine or supernatural intervention) escape from suffering through self-realisation. Sri Lanka’s benignly dominant Buddhist socio-cultural background naturally allows unrestricted freedom of religion, belief or non-belief for all its citizens, and makes the country a safe spiritual haven for them. The island’s Buddha Sasana (Dispensation of the Buddha) is the inalienable civilisational treasure that our ancestors of two and a half millennia have bequeathed to us. It is this enduring basis of our identity as a nation which bestows on us the personal and societal benefits of inestimable value mentioned in the AI summary given at the beginning of this essay.

It was this inherent national identity that the Sri Lankan contestant at the 72nd Miss World 2025 pageant held in Hyderabad, India, in May last year, Anudi Gunasekera, proudly showcased before the world, during her initial self-introduction. She started off with a verse from the Dhammapada (a Pali Buddhist text), which she explained as meaning “Refrain from all evil and cultivate good”. She declared, “And I believe that’s my purpose in life”. Anudi also mentioned that Sri Lanka had gone through a lot “from conflicts to natural disasters, pandemics, economic crises….”, adding, “and yet, my people remain hopeful, strong, and resilient….”.

“Ayubowan! I am Anudi Gunasekera from Sri Lanka. It is with immense pride that I represent my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka.

“I come from Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka’s first capital, and UNESCO World Heritage site, with its history and its legacy of sacred monuments and stupas…….”.

The “inspiring words” that Anudi quoted are from the Dhammapada (Verse 183), which runs, in English translation: “To avoid all evil/To cultivate good/and to cleanse one’s mind -/this is the teaching of the Buddhas”. That verse is so significant because it defines the basic ‘teaching of the Buddhas’ (i.e., Buddha Sasana; this is how Walpole Rahula Thera defines Buddha Sasana in his celebrated introduction to Buddhism ‘What the Buddha Taught’ first published in1959).

Twenty-five year old Anudi Gunasekera is an alumna of the University of Kelaniya, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in International Studies. She is planning to do a Master’s in the same field. Her ambition is to join the foreign service in Sri Lanka. Gen Z’er Anudi is already actively engaged in social service. The Saheli Foundation is her own initiative launched to address period poverty (i.e., lack of access to proper sanitation facilities, hygiene and health education, etc.) especially among women and post-puberty girls of low-income classes in rural and urban Sri Lanka.

Young Anudi is primarily inspired by her patriotic devotion to ‘my Motherland, a nation of resilience, timeless beauty, and a proud history, Sri Lanka’. In post-independence Sri Lanka, thousands of young men and women of her age have constantly dedicated themselves, oftentimes making the supreme sacrifice, motivated by a sense of national identity, by the thought ‘This is our beloved Motherland, these are our beloved people’.

The rescue and recovery of Sri Lanka from the evil aftermath of a decade of subversive ‘Aragalaya’ mayhem is waiting to be achieved, in every sphere of national engagement, including, for example, economics, communications, culture and politics, by the enlightened Anudi Gunasekeras and their male counterparts of the Gen Z, but not by the demented old stragglers lingering in the political arena listening to the unnerving rattle of “Time’s winged chariot hurrying near”, nor by the baila blaring monks at propaganda rallies.

Politically active monks (Buddhist bhikkhus) are only a handful out of the Maha Sangha (the general body of Buddhist bhikkhus) in Sri Lanka, who numbered just over 42,000 in 2024. The vast majority of monks spend their time quietly attending to their monastic duties. Buddhism upholds social and emotional virtues such as universal compassion, empathy, tolerance and forgiveness that protect a society from the evils of tribalism, religious bigotry and death-dealing religious piety.

Not all monks who express or promote political opinions should be censured. I choose to condemn only those few monks who abuse the yellow robe as a shield in their narrow partisan politics. I cannot bring myself to disapprove of the many socially active monks, who are articulating the genuine problems that the Buddha Sasana is facing today. The two bhikkhus who are the most despised monks in the commercial media these days are Galaboda-aththe Gnanasara and Ampitiye Sumanaratana Theras. They have a problem with their mood swings. They have long been whistleblowers trying to raise awareness respectively, about spreading religious fundamentalism, especially, violent Islamic Jihadism, in the country and about the vandalising of the Buddhist archaeological heritage sites of the north and east provinces. The two middle-aged monks (Gnanasara and Sumanaratana) belong to this respectable category. Though they are relentlessly attacked in the social media or hardly given any positive coverage of the service they are doing, they do nothing more than try to persuade the rulers to take appropriate action to resolve those problems while not trespassing on the rights of people of other faiths.

These monks have to rely on lay political leaders to do the needful, without themselves taking part in sectarian politics in the manner of ordinary members of the secular society. Their generally demonised social image is due, in my opinion, to three main reasons among others: 1) spreading misinformation and disinformation about them by those who do not like what they are saying and doing, 2) their own lack of verbal restraint, and 3) their being virtually abandoned to the wolves by the temporal and spiritual authorities.

(To be continued)

By Rohana R. Wasala ✍️

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result of this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoEnvironmentalists warn Sri Lanka’s ecological safeguards are failing

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDigambaram draws a broad brush canvas of SL’s existing political situation