Features

2024 SL presidential election: A significant shift towards liberal leftist politics

By Amarasiri de Silva

The 2024 Sri Lankan presidential election is considered a watershed moment for several key reasons. One of the most significant aspects is the peaceful transfer of power from a neoliberal administration to the left-oriented National People’s Power (NPP), led by Anura Kumara Dissanayake. The NPP, supported by the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP), marked a significant shift in the country’s political landscape. Historically, the JVP was involved in two armed uprisings in 1971 and 1989 in attempts to seize control through revolutionary means, both of which failed and were violently suppressed by the government.

The election results in 2024 reflect the public’s disillusionment with traditional political parties, particularly in light of the economic crises that have plagued Sri Lanka since 2022. Ranil Wickremesinghe, the neoliberal incumbent, played a pivotal role in stabilising the economy after widespread protests ousted the Rajapaksa government. However, despite his efforts to gain public trust, the voters, particularly the younger generation, demanded change and were drawn to the progressive and socialist policies of the NPP.

The peaceful electoral victory of the NPP, with such a revolutionary past, marks a new chapter in Sri Lankan politics. This election reflects a shift from armed struggle to democratic participation, cementing the NPP’s position as a legitimate political force. Moreover, this outcome challenges the entrenched political elite and signals a potential restructuring of Sri Lanka’s political and economic system. Originating from a farming community in Anuradhapura, Dissanayake embodies the character of an ordinary citizen, contrasting with the traditional rulers of the country who come from the Radala high caste or high-class families. This marks a significant shift in Sri Lanka’s political landscape.

The 2024 Sri Lankan presidential election result, which saw the victory of the leftist NPP, backed by the JVP, is not just a change of government but a direct challenge to the long-standing political elite that has dominated the country for decades. This entrenched political class, primarily represented by parties like the UNP and the SLFP, or the SLPP or Pohottuwa, has been heavily associated with neoliberal policies, dynastic politics, and a failure to address deep socio-economic inequalities. The victory of the NPP, a party with socialist leanings, marks a significant departure from this status quo.

The shift signals a potential restructuring of both the political and economic systems in Sri Lanka. Politically, the NPP’s rise reflects a growing rejection of elite control and the consolidation of power among a few families, like the Rajapaksas, Bandaranaikes, and Wickremesinghe’s political lineage. For years, these elites shaped the country’s policies, focusing on liberal economic reforms, often criticized for favouring the wealthy and exacerbating income disparities. The NPP’s success, bolstered by the JVP’s revolutionary past, suggests a new direction, focusing on redistributing political power and fostering a more egalitarian economic structure. Although the percentage increase of the NPP in the presidential election is attributed to the division between the UNP and the SJB, it is deeply rooted in the people’s desire for a fundamental system change. This is clearly reflected in the significant increase in the NPP’s voter base. This dramatic rise underscores the growing public demand for change and the NPP’s ability to capture the sentiments of a population eager for a new political direction. The electorate’s growing disillusionment with traditional political parties and failure to address socio-economic inequalities and governance issues has driven voters to seek an alternative in the NPP, reflecting a broader demand for transformative change in the country’s political and economic landscape.

Ranil Wickremesinghe, representing the UNP, and Sajith Premadasa, leading the SJB, have each garnered substantial support. However, their division has fragmented the votes that would otherwise likely consolidate under one party. This indicates that if the UNP and SJB had remained unified or had formed a coalition, they would have likely outperformed the NPP, reducing the latter’s influence and growth in parliamentary electoral results.

The fragmentation in the centre-right and centre-left political spaces, dominated by the UNP and SJB, has thus contributed to a scenario where a previously smaller political force like the NPP can make significant gains, as the Opposition’s division has weakened their ability to retain a majority vote share. Therefore, the NPP’s rise does not solely reflect an increase in its inherent support but rather the strategic consequences of a divided Opposition.

Economically, the NPP victory signals a potential shift toward policies prioritising social welfare, public ownership, and economic equity. The neoliberal approach championed by past governments, which included deregulation, privatisation, and aligning with global financial institutions like the IMF, faced strong opposition from the NPP and JVP. The NPP has advocated for state intervention in key sectors, wealth redistribution, and addressing the economic needs of the working class, a stark contrast to the elite-driven policies that favoured corporate interests and foreign investments.

This outcome also challenges the traditional role of Sri Lanka in the global economy. As a small developing nation, Sri Lanka has long depended on foreign aid, loans, and investment from international actors, especially during its economic crisis. The NPP’s victory may signal a recalibration of these relationships, as the party has criticized the terms of engagement with global financial institutions, calling for more autonomy and a greater focus on domestic development. In summary, the 2024 election represents more than just a change in leadership; it signals a broader transformation in Sri Lanka’s political and economic system, aiming to dismantle elite control and refocus governance on social justice and economic equity.

Despite the strong backing of the NPP from the oppressed and working-class voters in the 2024 Sri Lankan Presidential Election, a noticeable gap emerged in support from ethnic minorities, particularly in the North and upcountry regions. These regions are home to significant and Muslim and Tamil populations, who have historically been marginalized and continue to face social, political, and economic discrimination.

While the NPP’s platform of social justice, equity, and anti-elite rhetoric resonated with many of the country’s Sinhalese working class, the party’s message did not seem to fully address the complex grievances and historical trauma faced by these ethnic minorities. The Tamil population in the Northern Province, for instance, has long held concerns over unresolved issues from the civil war, such as the demand for justice, truth-seeking for alleged war crimes, and a genuine political solution that would grant them greater autonomy. The electoral results from the Batticaloa district reveal that the Tamil population in the region has yet to demonstrate significant allegiance to the NPP in recent elections. Batticaloa, located in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka, is predominantly inhabited by Tamils and Muslims. Tamil nationalist sentiments and concerns over ethnic rights, governance, and autonomy have historically shaped the political landscape in this region.

The NPP, primarily identified with the Sinhala-majority JVP, has traditionally struggled to gain traction in the Tamil electorate. This is mainly due to the party’s historical associations and lack of focus on the specific grievances of the Tamil community, such as demands for regional autonomy, post-war reconciliation, and devolution of power. The NPP’s broader, more nationalist platform has not resonated as strongly with the Tamil voters, who tend to align with parties that explicitly advocate for Tamil rights and representation, such as the Tamil National Alliance (TNA) and other regional parties.

This trend was visible in the 2020 parliamentary elections and other recent elections. The NPP failed to make significant inroads in Batticaloa, with most Tamil voters favouring more localised, ethnic-based parties that they perceive as better representing their political aspirations. This lack of support for the NPP in Batticaloa can also be attributed to the deep-rooted ethnic tensions in Sri Lanka’s political sphere. Many Tamil voters may view the NPP as part of the broader Sinhala-majority political establishment, which has historically been in opposition to Tamil demands for autonomy and justice for wartime grievances. Thus, the Batticaloa results underscore the NPP’s challenges in gaining support among Tamil populations, who remain more aligned with parties that advocate for their specific ethnic and regional concerns. This reflects a broader pattern in Sri Lankan politics, where ethnic identities and regional issues often dictate voting patterns.

The NPP’s position on these matters, while generally supportive of reconciliation, may have been perceived as insufficiently robust or sensitive to the specific needs of the Tamil community. Similarly, in the upcountry regions, which Tamil-speaking plantation workers of Indian origin largely inhabit, there remains a deep history of socio-economic deprivation. While the NPP’s economic agenda could benefit these groups, there may have been doubts about whether the party could deliver on its promises, given its primary appeal to a predominantly Sinhalese electorate. Ethnic minorities in these areas may also have been wary of aligning with a party rooted in Sinhalese-majoritarian political culture despite the NPP’s efforts to position itself as a multi-ethnic, inclusive political force.

The gap in minority support likely reflects a broader historical pattern in Sri Lankan politics, where minority communities have been cautious about backing new political movements, especially those with a strong base among the Sinhalese majority. Instead, many of these voters may have supported more established minority-friendly parties or candidates, such as the TNA in the North or the UNP, which was traditionally seen as more accommodating to minority concerns. This divergence underscores the deep ethnic and regional cleavages that continue to shape Sri Lankan electoral politics, even in the context of a broader desire for change.

The 2024 presidential election results highlight significant challenges for the new NPP government, led by Anura Kumara Dissanayake. Despite their platform advocating for a unified and ethnically cohesive government, the election results show that the message has not fully resonated with the country’s ethnic minorities, particularly the Tamils in the North and the upcountry Tamil communities, as well as the Muslim population. This poses a significant challenge for the NPP, which must now find ways to reconcile these disparities while fostering ethnic harmony in both economic and political spheres.

The JVP, which forms the core of the NPP, has historically struggled to build a strong base among ethnic minorities. The JVP’s revolutionary roots and prior engagement in Sinhalese-majoritarian politics during the 1971 and 1989 uprisings may have contributed to a lingering perception among minorities that the party is more focused on Sinhalese interests. Although the NPP campaigned on a platform of equality and inclusivity, it seems that these promises did not sufficiently convince the Tamil and Muslim communities, who have long demanded autonomy, recognition of their identity, and solutions to lingering post-war grievances. For the Tamil population in the Northern Province, for instance, issues such as war crimes accountability, land rights, and devolution of power remain unresolved, and the NPP’s messaging on these fronts may have lacked the specificity or reassurance they were seeking.

In the upcountry regions, where Tamil-speaking plantation workers of Indian origin face entrenched socio-economic hardships, the NPP’s broader economic reforms, while potentially beneficial, did not seem to connect with the unique struggles of these communities. Similarly, Sri Lanka’s Muslim population has faced increasing marginalization and targeted violence in recent years, and the NPP’s ability to address these concerns may be viewed with skepticism, given the JVP’s lack of a strong track record in minority issues.

The new NPP government now faces a critical challenge: how to build trust with ethnic minorities and integrate them into its broader vision of economic and political development. Achieving ethnic harmony in a deeply divided country will require more than rhetoric; it will necessitate concrete policy measures that address these communities’ historical injustices and grievances. The NPP will need to engage in meaningful dialogue with minority leaders, create mechanisms for greater political autonomy in the North and East, and ensure that economic development reaches all parts of the country, especially those that have historically been left behind. These efforts are essential not only for the success of the NPP government but also for the long-term stability and unity of Sri Lanka.

The NPP enjoyed overwhelming support from Sinhalese-majority districts in southern Sri Lanka, particularly from areas like Hambantota, Matara, and Galle. These regions are traditionally strongholds of the working and middle classes, including lower-middle-class workers, small-scale farmers, and rural laborers, including fisher folk. Many in these communities have faced longstanding economic hardships exacerbated by social disparities, stagnating wages, and a lack of equitable development. The NPP’s promise of economic reform, social justice, and redistributive policies appealed to these voters, who saw the NPP as a chance for significant change after decades of economic neglect by successive governments.

However, this support also presents a challenge for the NPP government. These regions have high expectations for concrete improvements in living standards, income growth, and social equity. The disparity between wealthier urban centers and rural southern districts has deepened over the years, and many rural voters feel marginalized by neoliberal policies that have primarily benefited Colombo and other urban hubs. Issues like insufficient access to quality education, healthcare, infrastructure development, and fair wages are critical concerns for these communities.

To redress these grievances, the NPP government must focus on policies that address rural economic development, ensure better income distribution, and enhance social welfare systems. Programmes to improve agricultural productivity, provide subsidies for small businesses, and increase state investment in public services, like healthcare and education, will be key to bridging the socioeconomic gap. Additionally, addressing structural inequalities and creating more inclusive economic growth models will be necessary to ensure that the benefits of development are shared across the country, particularly in these southern districts that supported the NPP so strongly. In short, the NPP’s support base in the south reflects deep dissatisfaction with the status quo, and delivering on their expectations will require focused, equitable development strategies to tackle the economic and social challenges that have hindered growth in these communities.

Finally, in addition to the policies they propose for the country’s development, the NPP should consider adopting practical policies proposed by their Opposition, particularly the SJB.

An essential suggestion from the SJB involves introducing a system of digital economy, including providing a digital wallet for each individual. This system would allow citizens to manage their daily transactions and major purchases in a streamlined, secure digital format. Implementing such a policy could have far-reaching benefits for the new NPP government. Firstly, a digital economy with an integrated wallet system could increase government revenue by formalizing many aspects of the informal economy. It would enable a more efficient tax collection system, helping to reduce the gap between government expenditure and income. Moving towards a direct income tax system where financial transactions are monitored and taxed appropriately, this policy could generate significant revenue quickly. This would provide the necessary funds to meet the current fiscal challenges as the state grapples with a high expenditure-income gap that demands urgent solutions.

Moreover, the digital wallet could ease day-to-day financial transactions for citizens, fostering greater economic inclusivity, particularly among marginalized or underbanked communities. Creating more transparency and encouraging savings through digital means lay the foundation for a more modernized financial infrastructure.

As the NPP forms its new government, many are eager to see whether it will adopt such forward-thinking policies. Another key concern is how the NPP, with only three members in Parliament, will approach governance. There is speculation that the NPP might quickly dissolve Parliament and call for general elections. In such a scenario, the party could potentially gain enough seats to form a majority government. However, navigating the parliamentary process and creating a robust governance structure will be critical to maintaining the public’s trust and ensuring that policies like the digital economy are implemented effectively. I personally congratulate Anura Kumara Dissanayake, the new President of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka.

Features

How Black Civil Rights leaders strengthen democracy in the US

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

On being elected US President in 2008, Barack Obama famously stated: ‘Change has come to America’. Considering the questions continuing to grow out of the status of minority rights in particular in the US, this declaration by the former US President could come to be seen as somewhat premature by some. However, there could be no doubt that the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency proved that democracy in the US is to a considerable degree inclusive and accommodating.

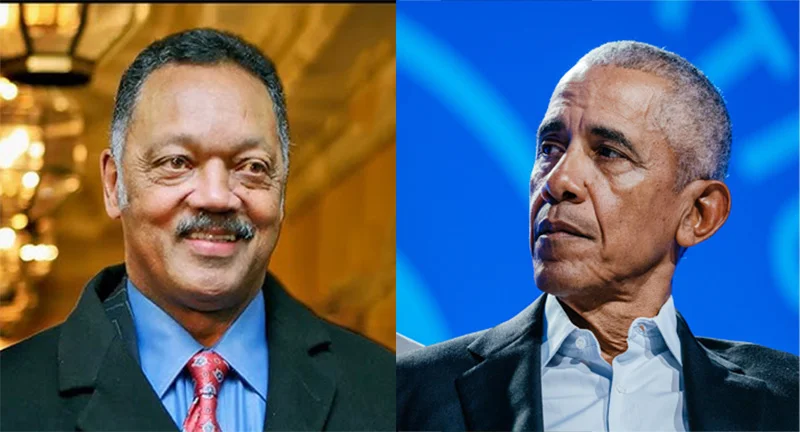

If this were not so, Barack Obama, an Afro-American politician, would never have been elected President of the US. Obama was exceptionally capable, charismatic and eloquent but these qualities alone could not have paved the way for his victory. On careful reflection it could be said that the solid groundwork laid by indefatigable Black Civil Rights activists in the US of the likes of Martin Luther King (Jnr) and Jesse Jackson, who passed away just recently, went a great distance to enable Obama to come to power and that too for two terms. Obama is on record as owning to the profound influence these Civil Rights leaders had on his career.

The fact is that these Civil Rights activists and Obama himself spoke to the hearts and minds of most Americans and convinced them of the need for democratic inclusion in the US. They, in other words, made a convincing case for Black rights. Above all, their struggles were largely peaceful.

Their reasoning resonated well with the thinking sections of the US who saw them as subscribers to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, for instance, which made a lucid case for mankind’s equal dignity. That is, ‘all human beings are equal in dignity.’

It may be recalled that Martin Luther King (Jnr.) famously declared: ‘I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed….We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.’

Jesse Jackson vied unsuccessfully to be a Democratic Party presidential candidate twice but his energetic campaigns helped to raise public awareness about the injustices and material hardships suffered by the black community in particular. Obama, we now know, worked hard at grass roots level in the run-up to his election. This experience proved invaluable in his efforts to sensitize the public to the harsh realities of the depressed sections of US society.

Cynics are bound to retort on reading the foregoing that all the good work done by the political personalities in question has come to nought in the US; currently administered by Republican hard line President Donald Trump. Needless to say, minority communities are now no longer welcome in the US and migrants are coming to be seen as virtual outcasts who need to be ‘shown the door’ . All this seems to be happening in so short a while since the Democrats were voted out of office at the last presidential election.

However, the last US presidential election was not free of controversy and the lesson is far too easily forgotten that democratic development is a process that needs to be persisted with. In a vital sense it is ‘a journey’ that encounters huge ups and downs. More so why it must be judiciously steered and in the absence of such foresighted managing the democratic process could very well run aground and this misfortune is overtaking the US to a notable extent.

The onus is on the Democratic Party and other sections supportive of democracy to halt the US’ steady slide into authoritarianism and white supremacist rule. They would need to demonstrate the foresight, dexterity and resourcefulness of the Black leaders in focus. In the absence of such dynamic political activism, the steady decline of the US as a major democracy cannot be prevented.

From the foregoing some important foreign policy issues crop-up for the global South in particular. The US’ prowess as the ‘world’s mightiest democracy’ could be called in question at present but none could doubt the flexibility of its governance system. The system’s inclusivity and accommodative nature remains and the possibility could not be ruled out of the system throwing up another leader of the stature of Barack Obama who could to a great extent rally the US public behind him in the direction of democratic development. In the event of the latter happening, the US could come to experience a democratic rejuvenation.

The latter possibilities need to be borne in mind by politicians of the South in particular. The latter have come to inherit a legacy of Non-alignment and this will stand them in good stead; particularly if their countries are bankrupt and helpless, as is Sri Lanka’s lot currently. They cannot afford to take sides rigorously in the foreign relations sphere but Non-alignment should not come to mean for them an unreserved alliance with the major powers of the South, such as China. Nor could they come under the dictates of Russia. For, both these major powers that have been deferentially treated by the South over the decades are essentially authoritarian in nature and a blind tie-up with them would not be in the best interests of the South, going forward.

However, while the South should not ruffle its ties with the big powers of the South it would need to ensure that its ties with the democracies of the West in particular remain intact in a flourishing condition. This is what Non-alignment, correctly understood, advises.

Accordingly, considering the US’ democratic resilience and its intrinsic strengths, the South would do well to be on cordial terms with the US as well. A Black presidency in the US has after all proved that the US is not predestined, so to speak, to be a country for only the jingoistic whites. It could genuinely be an all-inclusive, accommodative democracy and by virtue of these characteristics could be an inspiration for the South.

However, political leaders of the South would need to consider their development options very judiciously. The ‘neo-liberal’ ideology of the West need not necessarily be adopted but central planning and equity could be brought to the forefront of their talks with Western financial institutions. Dexterity in diplomacy would prove vital.

Features

Grown: Rich remnants from two countries

Whispers of Lanka

I was born in a hamlet on the western edge of a tiny teacup bay named Mirissa on the South Coast of Sri Lanka. My childhood was very happy and secure. I played with my cousins and friends on the dusty village roads. We had a few toys to play with, so we always improvised our own games. On rainy days, the village roads became small rivulets on which we sailed paper boats. We could walk from someone’s backyard to another, and there were no fences. We had the freedom to explore the surrounding hills, valleys, and streams.

I was good at school and often helped my classmates with their lessons. I passed the General Certificate of Education (Ordinary Level) at the village school and went to Colombo to study for the General Certificate of Education (Advanced Level). However, I did not like Colombo, and every weekend I hurried back to the village. I was not particularly interested in my studies and struggled in specific subjects. But my teachers knew that I was intelligent and encouraged me to study hard.

To my amazement, I passed the Advanced Level, entered the University of Kelaniya, completed an honours degree in Economics, taught for a few months at a central college, became a lecturer at the same university, and later joined the Department of Census and Statistics as a statistician. Then I went to the University of Wales in the UK to study for an MSc.

The interactions with other international students in my study group, along with very positive recommendations from my professors, helped me secure several jobs in the oil-rich Middle Eastern countries, where I earned salaries unimaginable in Sri Lankan terms. During this period, without much thought, I entered a life focused on material possessions, social status, and excessive consumerism.

Life changes

Unfortunately, this comfortable, enjoyable life changed drastically in the mid-1980s because of the political activities of certain groups. Radicalised youths, brainwashed and empowered by the dynamics of vibrant leftist politics, killed political opponents as well as ordinary people who were reluctant to follow their orders. Their violent methods frightened a large section of Sri Lanka’s middle class into reluctantly accepting country-wide closures of schools, factories, businesses, and government offices.

My father’s generation felt a deep obligation to honour the sacrifices they had made to give us everything we had. There was a belief that you made it in life through your education, and that if you had to work hard, you did. Although I had never seriously considered emigration before, our sons’ education was paramount, and we left Sri Lanka.

Although there were regulations on what could be brought in, migrating to Sydney in the 1980s offered a more relaxed airport experience, with simpler security, a strong presence of airline staff, and a more formal atmosphere. As we were relocating permanently, a few weeks before our departure, we had organised a container to transport sentimental belongings from our home. Our flight baggage was minimal, which puzzled the customs officer, but he laughed when he saw another bulky item on a separate trolley. It was a large box containing a bookshelf purchased in Singapore. Upon discovering that a new migrant family was arriving in Australia with a 32-volume Encyclopaedia Britannica set weighing approximately 250 kilograms, he became cheerful, relaxed his jaw, and said, G’day!

Settling in Sydney

We settled in Epping, Sydney, and enrolled our sons in Epping Boys’ High School. Within one week of our arrival from Sri Lanka, we both found jobs: my wife in her usual accounting position in the private sector, and I was taken on by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). While working at the CAA, I sat the Australian Graduate Admission Test. I secured a graduate position with the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in Canberra, ACT.

We bought a house in Florey, close to my office in Belconnen. The roads near the house were eerily quiet. Back in my hometown of Pelawatta, outside Colombo, my life had a distinct soundtrack. I woke up every morning to the radios blasting ‘pirith’ from the nearby houses; the music of the bread delivery van announcing its arrival, an old man was muttering wild curses to someone while setting up his thambili cart near the junction, free-ranging ‘pariah’ dogs were barking at every moving thing and shadows. Even the wildlife was noisy- black crows gathered on the branches of the mango tree in front of the house to perform a mournful dirge in the morning.

Our Australian neighbours gave us good advice and guidance, and we gradually settled in. If one of the complaints about Asians is that they “won’t join in or integrate to the same degree as Australians do,” this did not apply to us! We never attempted to become Aussies; that was impossible because we didn’t have tanned skin, hazel eyes, or blonde hair, but we did join in the Australian way of life. Having a beer with my next-door neighbour on the weekend and a biannual get-together with the residents of the lane became a routine. Walking or cycling ten kilometres around the Ginninderra Lake with a fit-fanatic of a neighbour was a weekly ritual that I rarely skipped.

Almost every year, early in the New Year, we went to the South Coast. My family and two of our best friends shared a rented house near the beach for a week. There’s not much to do except mix with lots of families with kids, dogs on the beach, lazy days in the sun with a barbecue and a couple of beers in the evening, watching golden sunsets. When you think about Australian summer holidays, that’s all you really need, and that’s all we had!

Caught between two cultures

We tried to hold on to our national tradition of warm hospitality by organising weekend meals with our friends. Enticed by the promise of my wife’s home-cooked feast, our Sri Lankan friends would congregate at our place. Each family would also bring a special dish of food to share. Our house would be crammed with my friends, their spouses and children, the sound of laughter and loud chatter – English mingled with Sinhala – and the aroma of spicy food.

We loved the togetherness, the feeling of never being alone, and the deep sense of belonging within the community. That doesn’t mean I had no regrets in my Australian lifestyle, no matter how trivial they may have seemed. I would have seen migration to another country only as a change of abode and employment, and I would rarely have expected it to bring about far greater changes to my psychological role and identity. In Sri Lanka, I have grown to maturity within a society with rigid demarcation lines between academic, professional, and other groups.

Furthermore, the transplantation from a patriarchal society where family bonds were essential to a culture where individual pursuit of happiness tended to undermine traditional values was a difficult one for me. While I struggled with my changing role, my sons quickly adopted the behaviour and aspirations of their Australian peers. A significant part of our sons’ challenges lay in their being the first generation of Sri Lankan-Australians.

The uniqueness of the responsibilities they discovered while growing up in Australia, and with their parents coming from another country, required them to play a linguistic mediator role, and we, as parents, had to play the cultural mediator role. They were more gregarious and adaptive than we were, and consequently, there was an instant, unrestrained immersion in cultural diversity and plurality.

Technology

They became articulate spokesmen for young Australians growing up in a world where information technology and transactions have become faster, more advanced, and much more widespread. My work in the ABS for nearly twenty years has followed cycles, from data collection, processing, quality assurance, and analysis to mapping, research, and publishing. As the work was mainly computer-based and required assessing and interrogating large datasets, I often had to depend heavily on in-house software developers and mainframe programmers. Over that time, I have worked in several areas of the ABS, making a valuable contribution and gaining a wide range of experience in national accounting.

I immensely valued the unbiased nature of my work, in which the ABS strived to inform its readers without the influence of public opinion or government decisions. It made me proud to work for an organisation that had a high regard for quality, accuracy, and confidentiality. I’m not exaggerating, but it is one of the world’s best statistical organisations! I rubbed shoulders with the greatest statistical minds. The value of this experience was that it enabled me to secure many assignments in Vanuatu, Fiji, East Timor, Saudi Arabia, and the Solomon Islands through the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund after I left the ABS.

Living in Australia

Studying and living in Australia gave my sons ample opportunities to realise that their success depended not on acquiring material wealth but on building human capital. They discovered that it was the sum total of their skills embodied within them: education, intelligence, creativity, work experience and even the ability to play basketball and cricket competitively. They knew it was what they would be left with if someone stripped away all of their assets. So they did their best to pursue their careers on that path and achieve their life goals. Of course, the healthy Australian economy mattered too. As an economist said, “A strong economy did not transform a valet parking attendant into a professor. Investment in human capital did that.”

Nostalgia

After living in Australia for several decades, do I miss Sri Lanka? Which country deserves my preference, the one where I was born or the one to which I migrated? There is no single answer; it depends on opportunities, prospects, lifestyle, and family. Factors such as the cost of living, healthcare, climate, and culture also play significant roles in shaping this preference. Tradition in a slow-motion place like Sri Lanka is an ethical code based on honouring those who do things the same way you do, and dishonour those who don’t. However, in Australia, one has the freedom to express oneself, to debate openly, to hold unconventional views, to be more immune to peer pressure, and not to have one’s every action scrutinised and discussed.

For many years, I have navigated the challenges of cultural differences, conflicting values, and the constant negotiation of where I truly ‘belong.’ Instead of yearning for a ‘dream home’ where I once lived, I have struggled, and to some extent succeeded, to find a home where I live now. This does not mean I have forgotten or discarded my roots. As one Sri Lankan-Australian senior executive remarked, “I have not restricted myself to the box I came in… I was not the ethnicity, skin colour, or lack thereof, of the typical Australian… but that has been irrelevant to my ability to contribute to the things which are important to me and to the country adopted by me.” Now, why do I live where I live – in that old house in Florey? I love the freshness of the air, away from the city smog, noisy traffic, and fumes. I enjoy walking in the evening along the tree-lined avenues and footpaths in my suburb, and occasionally I see a kangaroo hopping along the nature strip. I like the abundance of trees and birds singing at my back door. There are many species of birds in the area, but a common link with ours is the melodious warbling of resident magpies. My wife has been feeding them for several years, and we see the new fledglings every year. At first light and in the evening, they walk up to the back door and sing for their meal. The magpie is an Australian icon, and I think its singing is one of the most melodious sounds in the suburban areas and even more so in the bush.

by Siri Ipalawatte

Features

Big scene for models…

Modelling has turned out to be a big scene here and now there are lots of opportunities for girls and boys to excel as models.

Of course, one can’t step onto the ramp without proper training, and training should be in the hands of those who are aware of what modelling is all about.

Rukmal Senanayake is very much in the news these days and his Model With Ruki – Model Academy & Agency – is responsible for bringing into the limelight, not only upcoming models but also contestants participating in beauty pageants, especially internationally.

On the 29th of January, this year, it was a vibrant scene at the Temple Trees Auditorium, in Colombo, when Rukmal introduced the Grey Goose Road To Future Model Hunt.

Tharaka Gurukanda … in

the scene with Rukmal

This is the second Model Hunt to be held in Sri Lanka; the first was in 2023, at Nelum Pokuna, where over 150 models were able to showcase their skills at one of the largest fashion ramps in Sri Lanka.

The concept was created by Rukmal Senanayake and co-founded by Tharaka Gurukanda.

Future Model Hunt, is the only Southeast Asian fashion show for upcoming models, and designers, to work along and create a career for their future.

The Grey Goose Road To Future Model Hunt, which showcased two segments, brought into the limelight several models, including students of Ruki’s Model Academy & Agency and those who are established as models.

An enthusiastic audience was kept spellbound by the happenings on the ramp.

Doing it differently

Four candidates were also crowned, at this prestigious event, and they will represent Sri Lanka at the respective international pageants.

Those who missed the Grey Goose Road To Future Model Hunt, held last month, can look forward to another exciting Future Model Hunt event, scheduled for the month of May, 2026, where, I’m told, over 150 models will walk the ramp, along with several designers.

It will be held at a prime location in Colombo with an audience count, expected to be over 2000.

Model With Ruki offers training for ramp modelling and beauty pageants and other professional modelling areas.

Their courses cover: Ramp walk techniques, Posture and grooming, Pose and expression, Runway etiquette, and Photo shoots and portfolio building,

They prepare models for local and international fashion events, shoots, and competitions and even send models abroad for various promotional events.

-

Life style4 days ago

Life style4 days agoMarriot new GM Suranga

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoMinistry of Brands to launch Sri Lanka’s first off-price retail destination

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoMonks’ march, in America and Sri Lanka

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Rise of Takaichi

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWetlands of Sri Lanka:

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoThailand to recruit 10,000 Lankans under new labour pact

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoMassive Sangha confab to address alleged injustices against monks

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoIMF MD here