Features

JRJ encapsulates his autobiography in a 1992 post retirement book

by JR Jayewardene

(Excerpted from Men and Memories)

I was born on 17 September 17, 1906. My father was E.W. Jayawardene, K.C. and a Judge of the Supreme Court and my mother was Agnes Helen, the daughter of Tudugala Don Philip Wijewardene and his wife Helena Wijewardene. My maternal grandmother is remembered as a pious and noble lady who made munificent gifts for the restoration of the Kelaniya Raja Maha Viharaya, the 2,500 years old Sacred Buddhist shrine.

I was affectionately called ‘Dickie’ and was taught English and music by a Scottish governess, Miss Monro. At an early age I learned to play the piano. I entered the Royal College in 1911 and pursued my studies there till 1925 when I left Royal and entered the Ceylon University College. At the Royal College I was awarded the prize for general merit and the best speaker in 1925, the year in which I passed the London Matriculation Examination. I boxed, played cricket, rugger and football for the School, and played for the winning team in the annual Royal-Thomian encounter in 1925. At the University College I studied English, Logic, Latin and Economics.

In 1928 1 joined the Law College and the following year I was awarded the Hector Jayewardene Gold Medal for Oratory and the Walter Pereira Prize for Legal Research. In 1932 1 took my oath as an Advocate of the Supreme Court. The most symbolic act of my unconventional conduct as a law student was to hang of Mahatma Gandhi’s portrait in the parlour of the Law College. This sensational episode gained me much publicity at that time, for it amounted to a challenge thrown at the British Raj.

Born to a family of eminent lawyers whose private lives were played out in the public arena, I was propelled into politics in my youthful years. For a while my attention was directed to the Trade Union Movement launched by A.E. Goonesinha and in 1930 I addressed a meeting of Tramcar workers who were on strike.

Being the lawyer son of a lawyer father it did not take long for me to be recognized at Hulftsdorp. I never deviated from the high code of ethics of this learned profession. A voracious reader, I preferred history, current affairs, biography and political science to pure literature. The dynamic national liberation movement of India under the guidance of Mahatma Gandhi and his band of able lieutenants headed by Nehru was a source of inspiration to me.

I linked my fate with Elina B. Rupasinghe on February 28, 1935. Her affluence enabled me to pay more attention to politics and relegate law into the background although I was making my mark in the legal profession. We have one child, Ravindra, who qualified and worked as a Commercial Pilot in the Air Lanka untill ill-health compelled him to resign. He was a champion marksman representing his country in many International Games and led the Sri Lankan team to the Tokyo Olympics in 1954.

The Ceylon National Congress was dominated by politicians of Victorian vintage who followed the principles of liberal democracy of the era of Gladstone and Disraeli. The masses were either apolitical or showed total indifference to national problems. But in the neighbouring Sub-continent of India a mass movement was in full swing. Mahatma Gandhi, the frail ascetic, was the general who planned the Swaraj Movement, and his technique of Satyagraha or the power of Truth was the basis of the Indian freedom struggle. I was much impressed by the role played by Pandit Nehru for whom I developed a great affection.

In the Ceylon National Congress, I built up a significant relationship with D.S. Senanayake and the other elder statesmen. Always receptive to new ideas, a band of young radicals with myself bent our energies to transform the Ceylon National Congress into a mass political organization similar to the Indian National Congress. When I became the Joint Secretary of the Ceylon National Congress in 1940 with Dudley Senanayake we took steps to restructure and provide muscle and clout to this political forum which was dominated by members of elite families and representatives of the legal profession. We drafted a new Constitution and made great efforts to broadbase the organization. I led the Ceylon National Congress delegation consisting of J.E. Amaratunga and P.D.S. Jayasekare to the Annual Session of the Indian National Congress held at Ramgarh in March 1940.

The Ceylon National Congress nominated candidates for the Colombo Municipal Council elections in 1940 and I was elected as Member of the New Bazaar East Ward. At this time a group of young Marxists who had returned from English universities were busy organizing the urban working class and were active in rural areas as well. I cherished the friendship of Marxist intellectuals but I was not prepared to accept any ideology based on violence or which went against our national ethos, or conflicted with the ethics and tenets of Buddhism.

When I sought election to the State Council for the vacant seat of Kelaniya created by the resignation of Sir D.B. Jayatillake I had to face a formidable rival in E.W. Perera, the doughty freedom fighter. On April 18, 1943, I won the Kelaniya seat by a majority of 10,195 votes. On May 25, 1943, 1 took oath as Member of the State Council for Kelaniya and before long I became a recognized spokesman on major national issues. I introduced a bill in the State Council to make Sinhala the official language of Ceylon, later amended to include Tamil also.

Though immersed in national politics I also took a keen interest in Kelaniya. I never forgot to nurse the electorate and before long many rural hospitals, dispensaries and schools were built and numerous roads were constructed in the Kelaniya electorate which stretched from the banks of the Kelani River to the heartland of Siyane Korale. The State Council was no Mecca of mediocrities for it had a galaxy of brilliant young legislators and I worked hand in hand with them.

A founder member of the United National Party, which was formed in 1944 to contest the General Election of 1947, 1 was a follower of D.S. Senanayake and was offered the portfolio of Finance in the first Cabinet. Within a short period I understood the essentials of Public Finance and the first Six Year Plan was drawn up under my guidance. I had the reputation of being one of the hard working Ministers in D.S. Senanayake’s Cabinet, and I was able to get the best out of my subordinates as well as my advisers.

I become known in the international scene in September 1951 when I opposed Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko’s attempt to sabotage the Japanese Peace Treaty at San Francisco to the infinite relief of war-torn Japan. The sponsorship of the Colombo Plan also made me known in the international arena.

In Sir John Kotelawala’s Cabinet I was assigned the portfolio of Food and Agriculture. Before long storm clouds were gathering over the political horizon and the popularity of the United National Party slid down as the resurgent nationalist force with the accent on Buddhist revival and enthronement of Sinhala as the language gathered momentum.

In the General Elections held in April 1956 the party which ruled Ceylon since independence was beaten by the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna, headed by S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike. The UNP was reduced to a mere rump of eight seats and I was one of the many casualties in this electoral holocaust.

This reminds one of a remark in Winston Churchill’s War Memoirs, written about the great French Prime Minister Clemenceau who was rejected by the electorate. Churchill said, “Ingratitude towards their Leaders is a hallmark of a cultured race”. Perhaps he was making a veiled allusion or an insinuation against the British electorate which rejected his party at the polls after the Second World War. Kelaniya electorate rejected its representative in Parliament. I had done much for the electorate but was defeated by an intruder in April 1956.

The thinking in the country was that the UNP was a spent force which had outlived its purpose. Sir John was not inclined to attend Parliament and as a political party the UNP became rudderless and began to drift in a troubled sea of uncertainty. Dudley Senanayake had left the Party. I did not withdraw into a political wilderness. I advised my defeated friends that “In defeat, defiance should be the slogan.”

I was able to discern the dilemmas which the nation faced and assessed correctly the incompetence and inability of the new regime to deliver the goods. With neither an organization, ideology nor a program, it was destined to an untimely end. The Mahajana Eksath Peramuna possessed seeds of disintegration within itself. The `Sinhala Only’ Act was passed with much fanfare and the canker of communalism began to eat into the body politic of Ceylon. Very soon problems began to pile up and the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna began to tear at the seams.

The time was ripe for a review of the UNP’s future, the only party in the opposition based on principles of democracy and it fell to my lot to undertake this task. With a band of courageous and faithful followers I organized mass meetings and rallies throughout the country and took steps to correct the image of the UNP which was considered a conservative, capitalist party. Very soon I was able to pick up the broken pieces of the UNP and to amend them. Thus I was able to rebuild the fortunes of my party and the UNP was ready to face its adversaries in an electoral combat.

I championed the rights of the common man in Ceylon during the dark days of the MEP regime. When President, I was questioned by the ‘Leaders’ magazine as to my single greatest accomplishment during my political career. I mentioned that the most remarkable and fruitful thing I had achieved was keeping my party together and reviving it after the defeat in 1956. It is my firm conviction that Democracy lives in Sri Lanka today because of that.

The United National Party was prepared to stage a come back in 1960 mainly due to the Herculean efforts made to re-fashion and revitalize it. I regained my Kelaniya seat but it was a Pyrrhic victory for the UNP. Dudley Senanayake had rejoined the Party and his government lasted only for three months and the formidable Opposition was able to defeat it. In the General Elections of June 1960 the pendulum once more swung in favour of the SLFP, but the UNP was a sizeable party in the opposition and a force to be reckoned with in the country.

Dudley Senanayake became the Leader of the Opposition and I directed the assault on the establishment. The Marxists joined the SLFP in a grand coalition and proposed a bill to nationalize the Press. This attempt was foiled and the coalition government was defeated on a motion of ‘No-Confidence’.

In the General Election held in March 1965 the UNP defeated the coalition. I became the Minister of State. I rendered assistance to Premier Dudley Senanayake to launch the ‘Green Revolution’. I did much to develop tourism in Sri Lanka and the tourist boom we are witnessing today stems from those policies. I am an ardent environmentalist. I caused areas like the Horton Plains and Laggala to be declared as nature reserves. Though much was done to increase food production, yet the electorate once more gave a massive mandate to the United Front in the General Elections held in 1970.

There was much youth unrest in the country specially among educated young men from rural areas for want of employment opportunities and they backed the United Front. Though reduced in electoral strength the UNP with me as the Leader of the Opposition had to fight many a battle in the parliamentary arena and outside. The armed insurrection of those who were disillusioned with the United Front Government brought in its wake a plethora of problems. I was quite sincere when I wanted to render assistance to the government which was in great difficulties.

My attention was directed to the problem of the ‘functions of the Opposition’ in a parliamentary democracy or specially in a developing country like Sri Lanka. I questioned whether it was always necessary for the Opposition to oppose the party in power. My move to cooperate with the Government was vehemently opposed by a powerful section of the UNP.

Very soon cracks began to appear in the United Front Government and rule by ‘Emergency’ became the order of the day. Sri Lanka was in a total mess in every way. The protracted ‘Emergency’ coupled with the short-sighted economic policies of state ownership it pursued, paved the way for its inevitable collapse.

After the death of Dudley Senanayake, I was unanimously elected as the Leader of the UNP on April 26, 1973. I streamlined the party organization and built up a strong party and was prepared to confront the SLFP which disregarded the democratic rights of the people. By the strategy which I planned and executed, the UNP was in a position to deal a crippling blow on the SLFP and all the forces of the Left in the July 1977 election.

I took oath as Prime Minister on July 23, 1977. In a series of new measures which were a great wrench away from the short-sighted policies of the previous regime we swept away the muck and ineptitude of the former regime in a short time in a massive effort of cleaning the Augean stables. We refashioned a new Constitution, and a new page in the history of Sri Lanka was turned when I took oath of office as the first Executive President of Sri Lanka in February 1978.

We caused a major overhaul of economic and political priorities and paved the way for a liberalized, open economy and dismantled the previous government’s array of quotas, import restrictions and subsidies. These were some of the achievements after I became the Executive President. The accelerated Mahaweli Development Program which my government started has brought about a transformation in a vast area of the Dry Zone where a new civilization in being created.

The first Presidential Election was held on 20 October 20, 1982 and I won by a majority of over nine lakhs. In the first referendum held in Sri Lanka on 22 December 22, 1982, I received a mandate from the people to extend the term of Parliament in order to continue with the Development Program launched by me and the response of the people has continued to be positive.

It was my destiny to steer Sri Lanka through one of the traumatic periods of its history during the eighties. The very peace and tranquility of the island-nation was torn by violence and ethnic strife. It was during this period that the Sri Lanka-India Accord was signed between Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and myself.

Now I am no longer in active politics, but often watch the world around me, gripped by senseless violence born of suspicion, fear and by not understanding the perceptions and positions of one another in both the national and the international spheres. As I watch the events and personalities in these events, I hope e that the Buddhist spirit of compassion would prevail, and peace return to our island once again.

In this account of Men and Memories, which is not strictly an autobiography, I seek to present some autobiographical recollections and reflections which were inseparable from my life, and for over more than half a century of work. This I do in the hope that the contemporary and future generations would be enabled to understand the Agony and Ecstasy of Sri Lanka and her people with more insight, understanding and compassion.

Features

Following the Money: Tourism’s revenue crisis behind the arrival numbers – PART II

(Article 2 of the 4-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation)

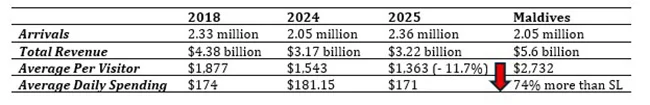

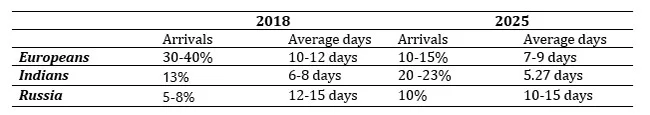

If Sri Lanka’s tourism story were a corporate income statement, the top line would satisfy any minister. Arrivals went up 15.1%, targets met, records broke. But walk down the statement and the story darkens. Revenue barely budges. Per-visitor yield collapses. The money that should accompany all those arrivals has quietly vanished, or, more accurately, never materialised.

If Sri Lanka’s tourism story were a corporate income statement, the top line would satisfy any minister. Arrivals went up 15.1%, targets met, records broke. But walk down the statement and the story darkens. Revenue barely budges. Per-visitor yield collapses. The money that should accompany all those arrivals has quietly vanished, or, more accurately, never materialised.

This is not a recovery. It is a volume trap, more tourists generating less wealth, with policymakers either oblivious to the math or unwilling to confront it.

Problem Diagnosis: The Paradox of Plenty:

The numbers tell a brutal story.

Read that again: arrivals grew 15.1% year-on-year, but revenue grew only 1.6%. The average tourist in 2025 left behind $181 less than in 2024, an 11.7% decline. Compared to 2018, the drop is even sharper. In real terms, adjusting for inflation and currency depreciation, each visitor in 2025 generates approximately 27-30% less revenue than in 2018, despite Sri Lanka being “cheaper” due to the rupee’s collapse. This is not marginal variance. This is structural value destruction. (See Table 1)

The math is simple and damning: Sri Lanka is working harder for less. More tourists, lower yield, thinner margins. Why? Because we have confused accessibility with competitiveness. We have made ourselves “affordable” through currency collapse and discounting, not through value creation.

Root Causes: The Five Mechanisms of Value Destruction

The yield collapse is not random. It is the predictable outcome of specific policy failures and market dynamics.

1. Currency Depreciation as False Competitiveness

The rupee’s collapse post-2022 has made Sri Lanka appear “cheap” to foreigners. A hotel room priced at $100 in 2018 might cost $70-80 in effective purchasing power today due to depreciation. Tour operators have aggressively discounted to fill capacity during the crisis recovery.

This creates the illusion of competitiveness. Arrivals rise because we are a “bargain.” But the bargain is paid for by domestic suppliers, hotels, transport providers, restaurants, staff, whose input costs (energy, food, imported goods) have skyrocketed in rupee terms while room rates lag in dollar terms.

The transfer is explicit: value flows from Sri Lankan workers and businesses to foreign tourists. The tourism “recovery” extracts wealth from the domestic economy rather than injecting it.

2. Market Composition Shift: Trading European Yields for Asian Volumes

SLTDA data shows a deliberate (or accidental—the policy opacity makes it unclear) shift in source markets. (See Table 2)

The problem is not that we attract Indians or Russians, it is that we attract them without strategies to optimise their yield. As the next article in this series will detail, Indian tourists average approximately 5.27 nights compared to the 8-9 night overall average, with lower per-day spending. We have built recovery on volume from price-sensitive segments rather than value from high-yield segments.

This is a choice, though it appears no one consciously made it. Visa-free entry, aggressive India-focused marketing, and price positioning have tilted the market mix without any apparent analysis of revenue implications.

3. Length of Stay Decline and Activity Compression

Average length of stay has compressed. While overall averages hover around 8-9 nights in recent years, the composition matters. High-yield European and North American tourists who historically spent 10-12 nights are now spending 7-9. Indian tourists spend 5-6 nights.

Shorter stays mean less cumulative spending, fewer experiences consumed, less distribution of value across the tourism chain. A 10-night tourist patronises multiple regions, hotels, guides, restaurants. A 5-night tourist concentrates spending in 2-3 locations, typically Colombo, one beach, one cultural site.

The compression is driven partly by global travel trends (shorter, more frequent trips) but also by Sri Lanka’s failure to develop compelling multi-day itineraries, adequate inter-regional connectivity, and differentiated regional experiences. We have not given tourists reasons to stay longer.

4. Infrastructure Decay and Experience Degradation

Tourists pay for experiences, not arrivals. When experiences degrade, airport congestion, poor road conditions, inadequate facilities at cultural sites, safety concerns, spending falls even if arrivals hold.

The 2024-2025 congestion at Bandaranaike International Airport, with reports of tourists nearly missing flights due to bottlenecks, is the visible tip. Beneath are systemic deficits: poor last-mile connectivity to tourism sites, deteriorating heritage assets, unregistered businesses providing sub-standard services, outbound migration of trained staff.

An ADB report notes that tourism authorities face resource shortages and capital expenditure embargoes, preventing even basic facility improvements at major revenue generators like Sigiriya (which charges $36 per visitor and attracts 25% of all tourists). When a site generates substantial revenue but lacks adequate lighting, safety measures, and visitor facilities, the experience suffers, and so does yield.

5. Leakage: The Silent Revenue Drain

Tourism revenue figures are gross. Net foreign exchange contributions after leakages, is rarely calculated or published.

Leakages include:

· Imported food, beverages, amenities in hotels (often 30-40% of operating costs)

· Foreign ownership and profit repatriation

· International tour operators taking commissions upstream (tourists book through foreign platforms that retain substantial margins)

· Unlicensed operators and unregulated businesses evading taxes and formal banking channels

Industry sources estimate leakages can consume 40-60% of gross tourism revenue in developing economies with weak regulatory enforcement. Sri Lanka has not published comprehensive leakage studies, but all indicators, weak licensing enforcement, widespread informal sector activity, foreign ownership concentration in resorts, suggest leakages are substantial and growing.

The result: even the $3.22 billion headline figure overstates actual net contribution to the economy.

The Way Forward: From Volume to Value

Reversing the yield collapse requires

systematic policy reorientation, from arrivals-chasing to value-building.

First

, publish and track yield metrics as primary KPIs. SLTDA should report:

· Revenue per visitor (by source market, by season, by purpose)

· Average daily expenditure (disaggregated by accommodation, activities, food, retail)

· Net foreign exchange contribution after documented leakages

· Revenue per room night (adjusted for real exchange rates)

Make these as visible as arrival numbers. Hold policy-makers accountable for yield, not just volume.

Second

, segment markets explicitly by yield potential. Stop treating all arrivals as equivalent. Conduct market-specific yield analyses:

· Which markets spend most per day?

· Which stays longest?

· Which distributes spending across regions vs. concentrating in Colombo/beach corridors?

· Which book is through formal channels vs. informal operators?

Target marketing and visa policies accordingly. If Western European tourists spend $250/day for 10 nights while another segment spends $120/day for 5 nights, the revenue difference ($2,500 vs. $600) dictates where promotional resources should flow.

Third

, develop multi-day, multi-region itineraries with compelling value propositions. Tourists extend stays when there are reasons to stay. Create integrated experiences:

· Cultural triangle + beach + hill country circuits with seamless connectivity

· Themed tours (wildlife, wellness, culinary, adventure) requiring 10+ days

· Regional spread of accommodation and experiences to distribute economic benefits

This requires infrastructure investment, precisely what has been neglected.

Fourth

, regulations to minimise leakages. Enforce licensing for tourism businesses. Channel bookings through formal operators registered with commercial banks. Tax holiday schemes should prioritise investments that maximise local value retention, staff training, local sourcing, domestic ownership.

Fifth

, stop using currency depreciation as a competitive strategy. A weak rupee makes Sri Lanka “affordable” but destroys margins and transfers wealth outward. Real competitiveness comes from differentiated experiences, quality standards, and strategic positioning, not from being the “cheapest” option.

The Hard Math: What We’re Losing

Let’s make the cost explicit. If Sri Lanka maintained 2018 per-visitor spending levels ($1,877) on 2025 arrivals (2.36 million), revenue would be approximately $4.43 billion, not $3.22 billion. The difference: $1.21 billion in lost revenue, value that should have been generated but wasn’t.

That $1.21 billion is not a theoretical gap. It represents:

· Wages not paid

· Businesses not sustained

· Taxes not collected

· Infrastructure not funded

· Development not achieved

This is the cost of volume-chasing without yield discipline. Every year we continue this model; we lock in value destruction.

The Policy Failure: Why Arrivals Theater Persists

Why do policymakers fixate on arrivals when revenue tells the real story?

Because arrivals are politically legible. A minister can tout “record tourist numbers” in a press conference. Revenue per visitor requires explanation, context, and uncomfortable questions about policy choices.

Arrivals are easy to manipulate upward, visa-free entry, aggressive discounting, currency depreciation. Yield is hard, it requires product development, market curation, infrastructure investment, regulatory enforcement.

Arrivals theater is cheaper and quicker than strategic transformation. But this is governance failure at its most fundamental. Tourism’s contribution to economic recovery is not determined by how many planes land but by how much wealth each visitor creates and retains domestically. Every dollar spent celebrating arrival records while ignoring yield collapse is a waste of dollars.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Sri Lanka’s tourism “boom” is real in volume, but it is a value bust. We are attracting more tourists and generating less wealth. The industry is working harder for lower returns. Margins are compressed, staff are paid less in real terms, infrastructure decays, and the net contribution to national recovery underperforms potential.

This is not sustainable. Eventually, operators will exit. Quality will degrade further. The “affordable” positioning will shift to “cheap and deteriorating.” The volume will follow yield down.

We have two choices: acknowledge the yield crisis and reorient policy toward value creation or continue arrivals theater until the hollowness becomes undeniable.

The money has spoken. The question is whether anyone in power is listening.

Features

Misinterpreting President Dissanayake on National Reconciliation

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has been investing his political capital in going to the public to explain some of the most politically sensitive and controversial issues. At a time when easier political choices are available, the president is choosing the harder path of confronting ethnic suspicion and communal fears. There are three issues in particular on which the president’s words have generated strong reactions. These are first with regard to Buddhist pilgrims going to the north of the country with nationalist motivations. Second is the controversy relating to the expansion of the Tissa Raja Maha Viharaya, a recently constructed Buddhist temple in Kankesanturai which has become a flashpoint between local Tamil residents and Sinhala nationalist groups. Third is the decision not to give the war victory a central place in the Independence Day celebrations.

Even in the opposition, when his party held only three seats in parliament, Anura Kumara Dissanayake took his role as a public educator seriously. He used to deliver lengthy, well researched and easily digestible speeches in parliament. He continues this practice as president. It can be seen that his statements are primarily meant to elevate the thinking of the people and not to win votes the easy way. The easy way to win votes whether in Sri Lanka or elsewhere in the world is to rouse nationalist and racist sentiments and ride that wave. Sri Lanka’s post independence political history shows that narrow ethnic mobilisation has often produced short term electoral gains but long term national damage.

Sections of the opposition and segments of the general public have been critical of the president for taking these positions. They have claimed that the president is taking these positions in order to obtain more Tamil votes or to appease minority communities. The same may be said in reverse of those others who take contrary positions that they seek the Sinhala votes. These political actors who thrive on nationalist mobilisation have attempted to portray the president’s statements as an abandonment of the majority community. The president’s actions need to be understood within the larger framework of national reconciliation and long term national stability.

Reconciler’s Duty

When the president referred to Buddhist pilgrims from the south going to the north, he was not speaking about pilgrims visiting long established Buddhist heritage sites such as Nagadeepa or Kandarodai. His remarks were directed at a specific and highly contentious development, the recently built Buddhist temple in Kankesanturai and those built elsewhere in the recent past in the north and east. The temple in Kankesanturai did not emerge from the religious needs of a local Buddhist community as there is none in that area. It has been constructed on land that was formerly owned and used by Tamil civilians and which came under military occupation as a high security zone. What has made the issue of the temple particularly controversial is that it was established with the support of the security forces.

The controversy has deepened because the temple authorities have sought to expand the site from approximately one acre to nearly fourteen acres on the basis that there was a historic Buddhist temple in that area up to the colonial period. However, the Tamil residents of the area fear that expansion would further displace surrounding residents and consolidate a permanent Buddhist religious presence in the present period in an area where the local population is overwhelmingly Hindu. For many Tamils in Kankesanturai, the issue is not Buddhism as a religion but the use of religion as a vehicle for territorial assertion and demographic changes in a region that bore the brunt of the war. Likewise, there are other parts of the north and east where other temples or places of worship have been established by the military personnel in their camps during their war-time occupation and questions arise regarding the future when these camps are finally closed.

There are those who have actively organised large scale pilgrimages from the south to make the Tissa temple another important religious site. These pilgrimages are framed publicly as acts of devotion but are widely perceived locally as demonstrations of dominance. Each such visit heightens tension, provokes protest by Tamil residents, and risks confrontation. For communities that experienced mass displacement, military occupation and land loss, the symbolism of a state backed religious structure on contested land with the backing of the security forces is impossible to separate from memories of war and destruction. A president committed to reconciliation cannot remain silent in the face of such provocations, however uncomfortable it may be to challenge sections of the majority community.

High-minded leadership

The controversy regarding the president’s Independence Day speech has also generated strong debate. In that speech the president did not refer to the military victory over the LTTE and also did not use the term “war heroes” to describe soldiers. For many Sinhala nationalist groups, the absence of these references was seen as an attempt to diminish the sacrifices of the armed forces. The reality is that Independence Day means very different things to different communities. In the north and east the same day is marked by protest events and mourning and as a “Black Day”, symbolising the consolidation of a state they continue to experience as excluding them and not empathizing with the full extent of their losses.

By way of contrast, the president’s objective was to ensure that Independence Day could be observed as a day that belonged to all communities in the country. It is not correct to assume that the president takes these positions in order to appease minorities or secure electoral advantage. The president is only one year into his term and does not need to take politically risky positions for short term electoral gains. Indeed, the positions he has taken involve confronting powerful nationalist political forces that can mobilise significant opposition. He risks losing majority support for his statements. This itself indicates that the motivation is not electoral calculation.

President Dissanayake has recognized that Sri Lanka’s long term political stability and economic recovery depend on building trust among communities that once peacefully coexisted and then lived through decades of war. Political leadership is ultimately tested by the willingness to say what is necessary rather than what is politically expedient. The president’s recent interventions demonstrate rare national leadership and constitute an attempt to shift public discourse away from ethnic triumphalism and toward a more inclusive conception of nationhood. Reconciliation cannot take root if national ceremonies reinforce the perception of victory for one community and defeat for another especially in an internal conflict.

BY Jehan Perera

Features

Recovery of LTTE weapons

I have read a newspaper report that the Special Task Force of Sri Lanka Police, with help of Military Intelligence, recovered three buried yet well-preserved 84mm Carl Gustaf recoilless rocket launchers used by the LTTE, in the Kudumbimalai area, Batticaloa.

These deadly weapons were used by the LTTE SEA TIGER WING to attack the Sri Lanka Navy ships and craft in 1990s. The first incident was in February 1997, off Iranativu island, in the Gulf of Mannar.

Admiral Cecil Tissera took over as Commander of the Navy on 27 January, 1997, from Admiral Mohan Samarasekara.

The fight against the LTTE was intensified from 1996 and the SLN was using her Vanguard of the Navy, Fast Attack Craft Squadron, to destroy the LTTE’s littoral fighting capabilities. Frequent confrontations against the LTTE Sea Tiger boats were reported off Mullaitivu, Point Pedro and Velvetiturai areas, where SLN units became victorious in most of these sea battles, except in a few incidents where the SLN lost Fast Attack Craft.

Carl Gustaf recoilless rocket launchers

The intelligence reports confirmed that the LTTE Sea Tigers was using new recoilless rocket launchers against aluminium-hull FACs, and they were deadly at close quarter sea battles, but the exact type of this weapon was not disclosed.

The following incident, which occurred in February 1997, helped confirm the weapon was Carl Gustaf 84 mm Recoilless gun!

DATE: 09TH FEBRUARY, 1997, morning 0600 hrs.

LOCATION: OFF IRANATHIVE.

FACs: P 460 ISRAEL BUILT, COMMANDED BY CDR MANOJ JAYESOORIYA

P 452 CDL BUILT, COMMANDED BY LCDR PM WICKRAMASINGHE (ON TEMPORARY COMMAND. PROPER OIC LCDR N HEENATIGALA)

OPERATED FROM KKS.

CONFRONTED WITH LTTE ATTACK CRAFT POWERED WITH FOUR 250 HP OUT BOARD MOTORS.

TARGET WAS DESTROYED AND ONE LTTE MEMBER WAS CAPTURED.

LEADING MARINE ENGINEERING MECHANIC OF THE FAC CAME UP TO THE BRIDGE CARRYING A PROJECTILE WHICH WAS FIRED BY THE LTTE BOAT, DURING CONFRONTATION, WHICH PENETRATED THROUGH THE FAC’s HULL, AND ENTERED THE OICs CABIN (BETWEEN THE TWO BUNKS) AND HIT THE AUXILIARY ENGINE ROOM DOOR AND HAD FALLEN DOWN WITHOUT EXPLODING. THE ENGINE ROOM DOOR WAS HEAVILY DAMAGED LOOSING THE WATER TIGHT INTEGRITY OF THE FAC.

THE PROJECTILE WAS LATER HANDED OVER TO THE NAVAL WEAPONS EXPERTS WHEN THE FACs RETURNED TO KKS. INVESTIGATIONS REVEALED THE WEAPON USED BY THE ENEMY WAS 84 mm CARL GUSTAF SHOULDER-FIRED RECOILLESS GUN AND THIS PROJECTILE WAS AN ILLUMINATER BOMB OF ONE MILLION CANDLE POWER. BUT THE ATTACKERS HAS FAILED TO REMOVE THE SAFETY PIN, THEREFORE THE BOMB WAS NOT ACTIVATED.

Sea Tigers

Carl Gustaf 84 mm recoilless gun was named after Carl Gustaf Stads Gevärsfaktori, which, initially, produced it. Sweden later developed the 84mm shoulder-fired recoilless gun by the Royal Swedish Army Materiel Administration during the second half of 1940s as a crew served man- portable infantry support gun for close range multi-role anti-armour, anti-personnel, battle field illumination, smoke screening and marking fire.

It is confirmed in Wikipedia that Carl Gustaf Recoilless shoulder-fired guns were used by the only non-state actor in the world – the LTTE – during the final Eelam War.

It is extremely important to check the batch numbers of the recently recovered three launchers to find out where they were produced and other details like how they ended up in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka?

By Admiral Ravindra C. Wijegunaratne

By Admiral Ravindra C. Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP and Bar, RSP, VSV, USP, NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc (Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defence Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoAll’s not well that ends well?

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoGREAT 2025–2030: Sri Lanka’s Green ambition meets a grid reality check