Features

Conversations with Pasindu Nimsara

By Uditha Devapriya

Somewhere in 2020 I was browsing the internet. It had been a long and hard day and I had spent hours writing some articles. I was exhausted. There are times when you burn out and times when you have to take a break. I was taking a break.

Somewhere in 2020 I was browsing the internet. It had been a long and hard day and I had spent hours writing some articles. I was exhausted. There are times when you burn out and times when you have to take a break. I was taking a break.

All of a sudden, I got a notification on my phone.

It was from Instagram. Someone, a friend I hadn’t met, had messaged me. He had asked me a question. It seemed a little cryptic.

“So, if even those venerated as national heroes adopted Western names, what does that tell us about their religious beliefs?”

The question was innocuous enough, but it took time to register. A few days earlier I had shared a passage from Kumari Jayawardena’s Nobodies to Somebodies about the Weerahannadige Fernandos, of which Veera Puran Appu was a scion. My friend had seen the post. He seemed genuinely curious, if intrigued.

I can’t remember the conversation now, since I have deactivated my old account. But I do recall my friend asking me some questions about ethnic identity, and I do recall responding that our perceptions of ethnicity are coloured by where we are, who we are, and most importantly how we see ourselves. I sensed he did not agree with everything I said, which was fine. I also sensed he wanted to know more. Which was finer.

That was my first encounter with Pasindu Nimsara Thennakoon. In the course of our chat I got to know that he was a decade younger to me, was studying in Colombo yet had been born more than a hundred miles away in Ratnapura, and was interested in science, hoping to become a doctor but acutely interested in history and culture.

“They put me into the History Club,”

he said by way of explaining that latter anomaly. “I didn’t have any say in the matter,” he added. I could sense he was grinning.

I soon realised who “they” were. A couple of months later, following a particularly nasty pandemic wave – this was at the peak of COVID-19 – I met Pasindu. He was accompanied by a friend of his. Both seemed bright and were enthusiastic about the subjects I was writing on, including art and history. The only difference was that while Pasindu had selected science for his A Levels, his friend had chosen Arts. I was told this was unusual. “Almost everyone in our circle did science or maths,” Pasindu remarked.

Pasindu’s friend, Uthpala Wijesuriya, has since charted his own path. I wrote on him to this paper last December. Pasindu, however, I have not written about. This is all the more inexplicable when considering that, for a good year and a half, it was partly his interest in history and anthropology that got me to delve in these areas.

Like Uthpala, Pasindu Nimsara entered his second school, Royal College, through the Grade Five Scholarship. This had been in 2014. He had secured high marks. Yet though he had been coveted back home, he felt out of place in Colombo. As I listened to his recollections of his first few days in his new home, I realised this may have been what first sparked his interest in history and art: subjects most of his peers normally did not take to.

When he shifted to Royal, Pasindu was boarded at the Hostel. Like most of his friends, he quickly found his footing there. Taking part in several activities and joining a few clubs and societies, he gradually realised where he wanted to be and what he wanted to do. Yet at one level, more so than his friends, he felt restless. He didn’t want to engage in one thing for long. For a while tried his hand at music, then discovered a passion for football, then joined the volleyball team, and then reverted to football.

All he knew was that he wanted to become a doctor. But his interest in medicine reflected a highly eclectic mind. He studied into the late hours, yet found the time to read whatever else he could. Among other things, he was fascinated by the role of culture.

It helped that he came from another part of the country. Every weekend, he would go back home. Every Monday morning, he would be in Colombo. This continued for a number of years, and it alerted him to the differences, and similarities, between these two worlds. The more he reflected on it, the more he wanted to explore.

In 2019 he did his O Levels. The following year he was appointed a Hostel Prefect. In 2021, he and Uthpala took part in, and led, several clubs and societies. These ended up being honoured and recognised by the school. Then, in 2022, Pasindu was appointed as one of two Deputy Head Prefects at the Hostel. Uthpala became Head Prefect.

This was a volatile year. The country had plunged into its worst economic crisis. The Hostel was shut down, then reopened. Classes were disrupted. Yet through it all, Pasindu and his friends managed to organise a Hostel Night. This was the first such Night organised after seven years. Coming just months after a series of protests had pushed a president of the country out, it seemed a breath of fresh air. Later, Pasindu was appointed as a Steward and a Senior Prefect. These were the highest honours a student could ever receive at Royal.

It was towards the end of 2021 that I began talking with Pasindu more extensively and seriously. Neither of us had much to do. I didn’t have a job, and he didn’t have classes to attend. Initially shy, guarded, and reticent, he slowly opened to me about his passion for football and his interest in culture. The latter often animated our discussions: at one level, it was almost as though it gave his life some meaning.

That had to do with where he came from. From an early age, Pasindu was taken to temples and shrines in Ratnapura. Participating in pageants and ceremonies, he opened himself to a strange new world. Though remote and outlying, his village exercised an influence on his mind. As he immersed himself in its customs, traditions, and rituals, he came to appreciate his culture and grew more conscious of his inheritance.

This was a world I had never really been privy to, which seemed almost otherworldly to me. In Colombo, a Buddhist temple is a place to be visited, hardly a regular haunt. Yet in places like Ratnapura it serves a crucial function, sustaining entire villages. Old temples held a certain fascination for me, their murals and architecture in particular. But for Pasindu, even after he settled in Colombo, they fulfilled a higher purpose.

It was at this point that, out of the blue, both of us began reading on anthropology. At the time I was working as the research coordinator for Dr SinhaRaja Tammita-Delgoda’s massive study of George Keyt. Somehow or the other I got to talk with Dr Ellen Dissanayake. As I read her writings on culture, I passed them over to Pasindu. He began reading them with much interest. He was particularly taken up by Dissanayake’s point that culture, at the end of the day, had a purpose to it, and that it evolved from the simplest ceremonies.

“Subtract the chant, music, masks, dance, painting, and you’re left with nothing.”

For some reason, this resonated with Pasindu. By way of adding to Dissanayake’s point he commented, perhaps half-in-jest:

“Subtract culture and you are left with nothing.”

Pasindu’s near mystical respect for culture soon clashed with my self-professed agnosticism. When conversations turned to arguments, we invoked one example after another to counter each other. He refused to be disarmed by my arguments. At one level we were talking at cross-purposes. But that was because, though it took time for us to realise it, he and I were operating within different frameworks.

Responding to the rationalist argument, that almost everything can be explained through science and reason, for instance, he countered that belief systems operate on a logic of its own. This is, of course, something social scientists have highlighted, but I suspect Pasindu has taken it a step further. It’s not that science can’t explain culture; of course it can. Yet an ordinary villager will not be swayed by rational explanations, even though he knows them to be true. This is an important point, but it tends to get ignored .

Take a very simple phenomenon: firewalking. As Carlo Fonseka’s experiments at Kataragama in the 1970s show, one doesn’t have to be blessed with divine aid to be able to walk on live coals. Yet Pasindu’s point is not that there isn’t a scientific rationale for this, rather that it is not relevant for those who prefer to believe in other explanations.

“A lot of people already know that these things are not the result of the power of God. Yet such beliefs get transferred from one generation to another. Kids may believe, but adults? No.”

I think that is an important argument. All too often, those who criticise beliefs and traditions do so from a moral high ground. But this is the wrong perspective to adopt, because when you place yourself above a belief system, the other side disregards your critique of that system, however valid it may be. My conversations with Pasindu have hence convinced me that we need to be more nuanced in our approach to culture.

In an intriguing semi-autobiographical essay, Gananath Obeyesekere remembers how his upbringing in a village outside Colombo helped mould his later career. He recalls the rites and rituals that became part of his childhood. These spurred his fascination with culture, art, literature, and later anthropology.

People like Pasindu are rare. Like Obeyesekere, they are a product of two worlds, and they often sway from the one to the other. Obeyesekere found his footing, yet went back to his roots. Pasindu also returns to them. Once in a while, he takes me to them too.

The other day he called me while on a bus from Ratnapura to Rakwana. Over the phone I could hear someone shouting, singing what sounded like religious homilies.

I asked him what it was.

“In Colombo, beggars sing baila,”

he observed. “Over here, they chant and sing Buddhist stanzas.”

After our call ended, I went back to another time, place, and conversation.

“Do you like to be an anthropologist?”

I asked Pasindu back then. “Definitely,” he replied.

“I always try to be.”

Uditha Devapriya is a regular commentator on history, art and culture, politics, and foreign policy who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com. Together with Uthpala Wijesuriya, he heads U & U, an informal art and culture research collective.

Features

Counting cats, naming giants: Inside the unofficial science redefining Sri Lanka’s Leopards and Tuskers

For decades, Sri Lanka’s leopard numbers have been debated, estimated, and contested, often based on assumptions few outside academic circles ever questioned.

One of the most fundamental was that a leopard’s spots never change. That belief, long accepted as scientific fact, began to unravel not in a laboratory or lecture hall, but through thousands of photographs taken patiently in the wilds of Yala. At the centre of that quiet disruption stands Milinda Wattegedara.

Sri Lanka’s wilderness has always inspired photographers. Far fewer, however, have transformed photography into a data-driven challenge to established conservation science. Wattegedara—an MBA graduate by training and a wildlife researcher by pursuit—has done precisely that, building one of the most comprehensive independent identification databases of leopards and tuskers in the country.

“I consider myself privileged to have been born and raised in Sri Lanka,” Wattegedara says. “This island is extraordinary in its biodiversity. But admiration alone doesn’t protect wildlife. Accuracy does.”

Raised in Kandy, and educated at Kingswood College, where he captained cricket teams, up to the First XI, Wattegedara’s early years were shaped by discipline and long hours of practice—traits that would later define his approach to field research.

Though his formal education culminated in a Master’s degree in Business Administration from Cardiff Metropolitan University, his professional life gradually shifted toward Sri Lanka’s forests, grasslands, and coastal fringes.

From childhood, two species held his attention: the Sri Lankan leopard and the Asian elephant tusker. Both are icons. Both are elusive. And both, he argues, have been inadequately understood.

His response was methodical. Using high-resolution photography, Wattegedara began documenting individual animals, focusing on repeat sightings, behavioural traits, territorial ranges, and physical markers.

This effort formalised into two platforms—Yala Leopard Diary and Wild Tuskers of Sri Lanka—which function today as tightly moderated research communities rather than casual social media pages.

“My goal was never popularity,” he explains. “It was reliability. Every identification had to stand scrutiny.”

The results are difficult to dismiss. Through collaborative verification and long-term monitoring, his teams have identified over 200 individual leopards across Yala and Kumana National Parks and 280 tuskers across Sri Lanka.

Each animal—whether Jessica YF52 patrolling Mahaseelawa beach or Mahasen T037, the longest tusker bearer recorded in the wild—is catalogued with photographic evidence and movement history.

It was within this growing body of data that a critical inconsistency emerged.

“As injuries accumulated over time, we noticed subtle but consistent changes in rosette and spot patterns,” Wattegedara says. “This directly contradicted the assumption that these markings remain unchanged for life.”

That observation, later corroborated through structured analysis, had serious implications. If leopards were being identified using a limited set of spot references, population estimates risked duplication and inflation.

The findings led to the development of the Multipoint Leopard Identification Method, now internationally published, which uses multiple reference points rather than fixed pattern assumptions. “This wasn’t about academic debate,” Wattegedara notes. “It was about ensuring we weren’t miscounting an endangered species.”

The implications extend beyond Sri Lanka. Overestimated populations can lead to reduced protection, misplaced policy decisions, and weakened conservation urgency.

Yet much of this work has occurred outside formal state institutions.

“There’s a misconception that meaningful research only comes from official channels,” Wattegedara says. “But conservation gaps don’t wait for bureaucracy.”

That philosophy informed his role as co-founder of the Yala Leopard Centre, the world’s first facility dedicated solely to leopard education and identification. The Centre serves as a bridge between researchers, wildlife enthusiasts, and the general public, offering access to verified knowledge rather than speculation.

In a further step toward transparency, Artificial Intelligence has been introduced for automatic leopard identification, freely accessible via the Centre and the Yala Leopard Diary website. “Technology allows consistency,” he explains. “And consistency is everything in long-term studies.”

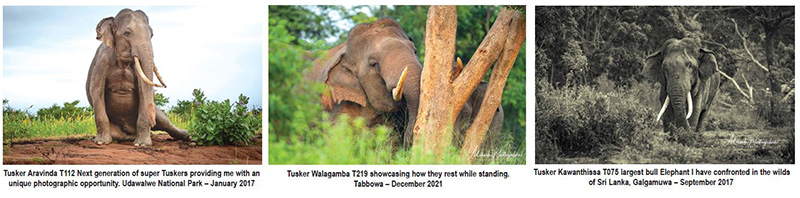

His work with tuskers mirrors the same precision. From Minneriya to Galgamuwa, Udawalawe to Kala Wewa, Wattegedara has documented generations of bull elephants—Arjuna T008, Kawanthissa T075, Aravinda T112—not merely as photographic subjects, but as individuals with lineage, temperament, and territory.

This depth of observation has also earned him recognition in wildlife photography, including top honours from the Photographic Society of Sri Lanka and accolades from Sanctuary Asia’s Call of the Wild. Still, he is quick to downplay awards.

“Photographs are only valuable if they contribute to understanding,” he says.

Today, Wattegedara’s co-authored identification guides on Yala leopards and Kala Wewa tuskers are increasingly referenced by researchers and field naturalists alike. His work challenges a long-standing divide between citizen science and formal research.

“Wildlife doesn’t care who publishes first,” he reflects. “It only responds to how accurately we observe it.”

In an era when Sri Lanka’s protected areas face mounting pressure—from tourism, infrastructure, and climate stress—the question of who counts wildlife, and how, has never been more urgent.

By insisting on precision, patience, and proof, Milinda Wattegedara has quietly reframed that conversation—one leopard, one tusker, and one verified photograph at a time.

By Ifham Nizam ✍️

Features

AI in Schools: Preparing the Nation for the Next Technological Leap

This summary document is based on an exemplary webinar conducted by the Bandaranaike Academy for Leadership & Public Policy ((https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TqZGjlaMC08). I participated in the session, which featured multiple speakers with exceptional knowledge and experience who discussed various aspects of incorporating artificial intelligence (AI) into the education system and other sectors.

There was strong consensus that this issue must be addressed early, before the nation becomes vulnerable to external actors seeking to exploit AI for their own advantage. Given her educational background, the Education Minister—and the Prime Minister—are likely to be fully aware of this need. This article is intended to support ongoing efforts in educational reform, including the introduction of AI education in schools for those institutions willing to adopt it.

Artificial intelligence is no longer a futuristic concept. Today, it processes vast amounts of global data and makes calculated decisions, often to the benefit of its creators. However, most users remain unaware of the information AI gathers or the extent of its influence on decision-making. Experts warn that without informed and responsible use, nations risk becoming increasingly vulnerable to external forces that may exploit AI.

The Need for Immediate Action

AI is evolving rapidly, leaving traditional educational models struggling to keep pace. By the time new curricula are finalised, they risk becoming outdated, leaving both students and teachers behind. Experts advocate immediate government-led initiatives, including pilot AI education programs in willing schools and nationwide teacher training.

“AI is already with us,” experts note. “We must ensure our nation is on this ‘AI bus’—unlike past technological revolutions, such as IT, microchips, and nanotechnology, which we were slow to embrace.”

Training Teachers and Students

Equipping teachers to introduce AI, at least at the secondary school level, is a crucial first step. AI can enhance creativity, summarise materials, generate lesson plans, provide personalised learning experiences, and even support administrative tasks. Our neighbouring country, India, has already begun this process.

Current data show that student use of AI far exceeds that of instructors—a gap that must be addressed to prevent misuse and educational malpractice. Specialists recommend piloting AI courses as electives, gathering feedback, and continuously refining the curriculum to prepare students for an AI-driven future.

Benefits of AI in Education

AI in schools offers numerous advantages:

· Fosters critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving skills

· Enhances digital literacy and ethical awareness

· Bridges the digital divide by promoting equitable AI literacy

· Supports interdisciplinary learning in medicine, climate science, and linguistics

· Provides personalised feedback and learning experiences

· Assists students with disabilities through adaptive technologies like text-to-speech and visual recognition

AI can also automate administrative tasks, freeing teachers to focus on student engagement and social-emotional development—a key factor in academic success.

Risks and Challenges

Despite its potential, AI presents challenges:

· Data privacy concerns and misuse of personal information

· Over-reliance on technology, reducing teacher-student interactions

· Algorithmic biases affecting educational outcomes

· Increased opportunities for academic dishonesty if assessments rely on rote memorisation

Experts emphasise understanding these risks to ensure the responsible and ethical use of AI.

Global and Local Perspectives

In India, the Central Board of Secondary Education plans to introduce AI and computational thinking from Grades 3 to 12 by 2026. Sri Lanka faces a similar challenge. Many university students and academics already rely on AI, highlighting the urgent need for a structured yet rapidly evolving national curriculum that incorporates AI responsibly.

The Way Forward

Experts urge swift action:

· Launch pilot programs in select schools immediately.

· Provide teacher training and seed funding to participating educational institutions.

· Engage universities to develop short AI and innovation training programs.

“Waiting for others to lead risks leaving us behind,” experts warn. “It’s time to embrace AI thoughtfully, responsibly, and inclusively—ensuring the whole nation benefits from its opportunities.”

As AI reshapes our world, introducing it in schools is not merely an educational initiative—it is a national imperative.

BY Chula Goonasekera ✍️

on behalf of LEADS forum admin@srilankaleads.com

Features

The Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

The Trump paradox is easily explained at one level. The US President unleashes American superpower and tariff power abroad with impunity and without contestation. But he cannot exercise unconstitutional executive power including tariff power without checks and challenges within America. No American President after World War II has exercised his authority overseas so brazenly and without any congressional referral as Donald Trump is getting accustomed to doing now. And no American President in history has benefited from a pliant Congress and an equally pliant Supreme Court as has Donald Trump in his second term as president.

Yet he is not having his way in his own country the way he is bullying around the world. People are out on the streets protesting against the wannabe king. This week’s killing of 37 year old Renee Good by immigration agents in Minneapolis has brought the City to its edge five years after the police killing of George Floyd. The lower courts are checking the president relentlessly in spite of the Supreme Court, if not in defiance of it. There are cracks in the Trump’s MAGA world, disillusioned by his neglect of the economy and his costly distractions overseas. His ratings are slowly but surely falling. And in an electoral harbinger, New York has elected as its new mayor, Zoran Mamdani – a wholesale antithesis of Donald Trump you can ever find.

Outside America it is a different picture. The world is too divided and too cautious to stand up to Trump as he recklessly dismantles the very world order that his predecessors have been assiduously imposing on the world for nearly a hundred years. A few recent events dramatically illustrate the Trump paradox – his constraints at home and his freewheeling abroad.

Restive America

Two days before Christmas, the US Supreme Court delivered a rare rebuke to the Trump Administration. After a host of rulings that favoured Trump by putting on hold, without full hearing, lower court strictures against the Administration, the Supreme Court by a 6-3 majority decided to leave in place a Federal Court ruling that barred Trump from deploying National Guard troops in Chicago. Trump quietly raised the white flag and before Christmas withdrew the federal troops he had controversially deployed in Chicago, Portland and Los Angeles – all large cities run by Democrats.

But three days after the New Year, Trump airlifted the might of the US Army to encircle Venezuela’s capital Caracas and spirit away the country’s President Nicolás Maduro, and his wife Celia Flores, all the way to New York to stand trial in an American Court. What is not permissible in any American City was carried out with absolute impunity in a foreign capital. It turns out the Administration has no plan for Venezuela after taking out Maduro, other than Trump’s cavalier assertion, “We’re going to run it, essentially.” Essentially, the Trump Administration has let Maduro’s regime without Maduro to run the country but with the US in total control of Venezuela’s oil.

Next on the brazen list is Greenland, and Secretary of State Marco Rubio who manipulated Maduro’s ouster is off to Copenhagen for discussions with the Danish government over the future of Greenland, a semi-autonomous part of Denmark. Military option is not off the table if a simple real estate purchase or a treaty arrangement were to prove infeasible or too complicated. That is the American position as it is now customarily announced from the White House podium by the Administration’s Press Secretary Karolyn Leavitt, a 28 year old Catholic woman from New Hampshire, who reportedly conducts a team prayer for divine help before appearing at the lectern to lecture.

After the Supreme Court ruling and the Venezuela adventure, the third US development relevant to my argument is the shooting and killing of a 37 year old white American woman by a US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officer in Minneapolis, at 9:30 in the morning, Wednesday, January 7th. Immediately, the Administration went into pre-emptive attack mode calling the victim a “deranged leftist” and a “domestic terrorist,” and asserting that the ICE officer was acting in self-defense. That line and the description are contrary to what many people know of the victim, as well as what people saw and captured on their phones and cameras.

The victim, Renee Nicole Good, was a mother of three and a prize-winning poet who self-described herself a “poet, writer, wife and mom.” A newcomer to Minneapolis from Colorado, she was active in the community and was a designated “legal observer of Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) activities,” to monitor interactions between ICE agents and civilian protesters that have become the norm in large immigrant cities in America. Renee Good was at the scene in her vehicle to observe ICE operations and community protesters.

In video postings that last a matter of nine seconds, two ICE officers are seen approaching Good’s vehicle and one of them trying to open her door; a bystander is heard screaming “No” as Good is seen trying to drive away; and a third ICE officer is seen standing in front of her moving vehicle, firing twice in the direction of the driver, moving to a side and firing a third time from the side. Good’s car is seen going out of control, careening and coming to a stop on a snowbank. Yet America is being bombarded with two irreconcilable narratives – one manufactured by Trump’s Administration and the other by those at the scene and everyone opposed to the regime.

It adds to the explosiveness of the situation that Good was shot and killed not far from where George Folyd was killed, also in Minneapolis, on 25th May, 2020, choked under the knee of a heartless policeman. And within 48 hours of Good’s killing, two Americans were shot and injured by two federal immigration agents, in Portland, Oregon, on the Westcoast. Trump’s attack on immigrants and the highhanded methods used by ICE agents have become the biggest flashpoint in the political opposition to the Trump presidency. People are organizing protests in places where ICE agents are apprehending immigrants because those who are being aggressively and violently apprehended have long been neighbours, colleagues, small business owners and students in their communities.

Deportation of illegal immigrants is not something that began under Trump. It has been going on in large numbers under all recent presidents including Obama and Biden. But it has never been so cruel and vicious as it is now under Trump. He has turned it into a television spectacle and hired large number of new ICE agents who are politically prejudiced and deployed them without proper training. They raid private homes and public buildings, including schools, looking for immigrants. When faced with protesters they get into clashes rather than deescalating the situation as professional police are trained to do. There is also the fear that the Administration may want to escalate confrontations with protesters to create a pretext for declaring martial law and disrupt the midterm congressional elections in November this year.

But the momentum that Trump was enjoying when he began his second term and started imposing his executive authority, has all but vanished and all within just one year in office. By the time this piece appears in print, the Supreme Court ruling on Trump’s tariffs (expected on Friday) may be out, and if as expected the ruling goes against Trump that will be a massive body blow to the Administration. Trump will of course use a negative court ruling as the reason for all the economic woes under his presidency, but by then even more Americans would have become tired of his perpetually recycled lies and boasts.

An Obliging World

To get back to my starting argument, it is in this increasingly hostile domestic backdrop that Trump has started looking abroad to assert his power without facing any resistance. And the world is obliging. The western leaders in Europe, Canada and Australia are like the three wise monkeys who will see no evil, hear no evil and speak no evil – of anything that Trump does or fails to do. Their biggest fear is about the Trump tariffs – that if they say anything critical of Trump he will magnify the tariffs against their exports to the US. That is an understandable concern and it would be interesting to see if anything will change if the US Supreme Court were to rule against Trump and reject his tariff powers.

Outside the West, and with the exception of China, there is no other country that can stand up to Trump’s bullying and erratic wielding of power. They are also not in a position to oppose Trump and face increased tariffs on their exports to the US. Putin is in his own space and appears to be assured that Trump will not hurt him for whatever reason – and there are many of them, real and speculative. The case of the Latin American countries is different as they are part of the Western Hemisphere, where Trump believes he is monarch of all he surveys.

After more than a hundred years of despising America, many communities, not just regimes, in the region seem to be warming up to Trump. The timing of Trump’s sequestering of Venezuela is coinciding with a rising right wing wave and regime change in the region. An October opinion poll showed 53% of Latin American respondents reacting positively to a then potential US intervention in Venezuela while only 18% of US respondents were in favour of intervention. While there were condemnations by Latin American left leaders, seven Latin American countries with right wing governments gave full throated support to Trump’s ouster of Maduro.

The reasons are not difficult to see. The spread of crime induced by the commerce of cocaine has become the number one concern for most Latin Americans. The socio-religious backdrop to this is the evangelisation of Christianity at the expense of the traditional Catholic Church throughout Latin America. And taking a leaf from Trump, Latin Americans have also embraced the bogey of immigration, mainly influenced by the influx of Venezuelans fleeing in large numbers to escape the horrors of the Maduro regime.

But the current changes in Latin America are not necessarily indicative of a durable ideological shift. The traditional left’s base in the subcontinent is still robust and the recent regime changes are perhaps more due to incumbency fatigue than shifts in political orientations. The left has been in power for the greater part of this century and has not been able to provide answers to the real questions that preoccupied the people – economic affordability, crime and cocaine. It has not been electorally smart for the left to ignore the basic questions of the people and focus on grand projects for the intelligentsia. Exhibit #1 is the grand constitutional project in Chile under outgoing President Gabriel Borich, but it is not the only one. More romantic than realistic, Boric’s project titillated liberal constitutionalists the world over, but was roundly rejected by Chileans.

More importantly, and sooner than later, Trump’s intervention in Venezuela and his intended takeover of the country’s oil business will produce lasting backlashes, once the initial right wing euphoria starts subsiding. Apart from the bully force of Trump’s personality, the mastermind behind the intervention in Venezuela and policy approach towards Latin America in general, is Secretary of State Marco Rubio, the former Cuban American Senator from Florida and the principal leader of the group of Cuban neocons in the US. His ultimate objective is said to be achieving regime change in Cuba – apparently a psychological settling of scores on behalf Cuban Americans who have been dead set against Castro’s Cuba after the overthrow of their beloved Batista.

Mr. Rubio is American born and his parents had left Cuba years before Fidel Castro displaced Fulgencio Batista, but the family stories he apparently grew up hearing in Florida have been a large part of his self-acknowledged political makeup. Even so, Secretary Rubio could never have foreseen a situation such as an externally uncontested Trump presidency in which he would be able to play an exceptionally influential role in shaping American policy for Latin America. But as the old Burns’ poem rhymes, “The best-laid plans of men and mice often go awry.”

by Rajan Philips ✍️

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoInterception of SL fishing craft by Seychelles: Trawler owners demand international investigation

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

Features1 day ago

Features1 day agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoBroad support emerges for Faiszer’s sweeping proposals on long- delayed divorce and personal law reforms

-

News1 day ago

News1 day ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament