Features

Ranasinghe Premadasa Birth Centenary – An evergreen leader

By Tisaranee Gunasekera

“All theory is grey… But forever green is the tree of life. “Goethe (Faust)

For three months in late 1990’s, American author and political activist Barbara Ehrenreich lived the life of a low-wage worker. She wanted to discover, first hand, how President Bill Clinton’s welfare reforms were impacting on the lives of the working poor. Her experiences gave birth to her most celebrated book, Nickle and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in America. In it, she focuses on the phenomenon of employed-homeless, workers who often do more than one job but are still unable to afford a roof over their heads. The conjunction of low wages and high rents create poverty traps from which few workers escape, Ehrenreich notes.

Almost 20 years later, sociologist Matthew Desmond in his book, Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City, demonstrated the cardinal role played by housing (or the lack of it) in perpetuating and exacerbating poverty in America. “Fewer and fewer families can afford a roof over their head. This is among the most urgent and pressing issues facing America today… We have failed to fully appreciate how deeply housing is implicated in the creation of poverty.”

According to Jan-Feb 2024 Household Pulse Survey, homelessness in America increased by 48% since 2015; and an estimated 37% of tenants say they are very or somewhat likely to be evicted in the next two months. The European condition is no better. “Unaffordable rent and property prices are turning into a political battleground,” The Guardian warned in May. The only exception is Vienna. 60% of Viennese live in subsidised housing. The city builds 6,000-7,000 subsidised housing units each year funded by a 1% tax on all salaries.

The Viennese exception is a legacy of Red Vienna (1918-1934 – when the Austrian capital was controlled by the Social Democratic Party) which was defined largely by its housing policy; the city built more than 60,000 new housing units. Sri Lanka, in 1979, embarked on a journey even more ambitious, to build 100,000 houses in three years. When Ranasinghe Premadasa unveiled his inaugural housing programme, it was ridiculed by the Opposition, stonewalled by the UNP cabinet, and criticised by the World Bank and the IMF. The mere thought of building 100,000 housing units in three years, and for the poor, was dismissed as a waste, an inflation-creator, and delusional.

But Premadasa would not be stopped. Like other top leaders of the UNP, he was eyeing the presidency and housing was going to be his ‘qualifier’ for the top job. Those politico-electoral imperatives apart, he understood the nexus between homelessness and politico-social and familial stability. During his tenure as a Colombo Municipal Councillor, he had spearheaded the building of flats in Saunders Place as part of a slum-clearance programme. As the Junior Minister of Housing in the 1965-70 government, he had built the Maligawatte Housing Scheme. As he put it, “Shelter is not charity. It is a necessity.”

Born and bred in Keselwatte, Sri Lanka’s equivalent of the old Harlem, Premadasa knew well the bitter anger and despair of the marginalised. Homelessness was a time-bomb waiting to explode, he understood, especially in the context of the rapid but unbalanced growth which resulted from the opening up of the economy after 1977. He regarded housing as a major stabiliser, a way of giving the poor a stake in the system.

Idealism and Realism

According to the UN special rapporteur on the right to adequate housing, homelessness is the ‘social issue of the 21st Century’. The seeds of this burgeoning crisis was sown in the final decades of the 20th Century, with the political de-prioritisation of the issue of housing/homelessness. The category of ‘structural homelessness’ came into being, an ipso facto justification of political indifference and policy neglect. Shelter was left to the vagaries of individual fortunes and the free play of market forces. Homeless encampments became the norm, eviction a super-profitable business.

The Lankan experiment under the leadership of Premadasa in battling homelessness was doubly remarkable because it unfolded against this background of global indifference. And, contrary to the confident predictions of naysayers on the left and the right, the 100,000 Houses Programme worked. “The targets were reached and exceeded by anything between 15%-30% – an unparalleled success in a government Housing Programme in a Third World Country,” wrote Prof KM de Silva. (Sri Lanka and the International Year of Shelter for the Homeless). According to a report by the United Nation’s Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, “The programme proved to be a success in terms of…target achievement, employment generation through the development of construction industry, and the ‘benign’ effect in the rental market” (Low cost shelter project in Sri Lanka – ESCAP). “Shelter (is) a field in which idealism and realism can blend to the advantage of all,” Premadasa had stated in his 1987 speech to the International Union of Architects. His programme, with its broad vision and hard practicality, certainly fitted the bill.

While 100,000 Houses programme was a success in target-achievement, it also revealed the limits of state as house-builder, especially in a rural setting. It was also too costly and too centralised. These lessons were incorporated into the next stage of the Housing adventure – the One Million Houses programme launched in 1984. Unlike the top-down method of the first phase, the second and third phases (1.5Milliion Houses programme) opted for a participatory model, involving beneficiaries at every stage of the process from planning to construction. The state’s role scaled down to that of assister.

“What we see here is a kind of respect for the poor and their abilities and capacities, or the trust that, if they are given some guidance and resources, they will be able to understand their own needs and respond to their housing needs in a better way…” Colombo Urban Lab researcher Meghal Perera told a regional seminar on shelter in 2022. “First of all, the state allowed the people to design their own houses. There are stories of how every single household in this programme was given a file about the loans they could obtain. They were also given a square rule paper for them to design their own houses in the way they wanted. Secondly, there were community building guidelines and rules specific to particular low-income settlements… This programme called for conversations and workshops where women were able to talk about matters…” (The Morning – 14.10.2022).

According to an island-wide research project carried out by the Premadasa Centre in the mid 1990’s, 34.2% of the recipients of the housing programmes were workers, 22.6% were labourers, 18.2% were cultivators, 9.2% were petty traders, 11.8% were self-employed or salaried employees. Low-wage earners who wouldn’t have been able to afford a house of their own, perhaps ever; employed-homeless turned into homeowners.

“For the last thirty years…when asking ourselves whether we support a proposal or initiative, we have not asked, is it good or bad?” historian Tony Judt wrote. “Instead we inquire: Is it efficient? Is it productive? Would it benefit gross domestic product? Will it contribute to growth? This propensity to avoid moral considerations, to restrict ourselves to issues of profit and loss—economic questions in the narrowest sense—is not an instinctive human condition. It is an acquired taste” (London Review of Books – 17.12.2009).

Ranasinghe Premadasa’s approach to development was conspicuous by the absence of such a purely economistic approach and the conscious incorporation of peoples’ interests as a primary measure of the desirability or undesirability of an economic policy. For Premadasa poverty was not just an economic problem to alleviate, a matter of numbers and percentages. He could look beyond the figures and see the people because he grew up among them, and continued to live with them even as president. Inside the Sucharitha Complex where he lived, there was even a school for the children of the area. Free of any theoretical bondage or ideological baggage, Premadasa was able to mix-and-match, discarding what didn’t work and bettering what did.

As Sirisena Cooray, his political companion and friend of four decades, wrote, “Mr. Premadasa had his own very different approach to developmental issues; his notion of slum clearance is an example of this. Usually slum clearance means the forcible eviction of the people living in slums to areas outside the city and developing these city locations for commercial purposes… This is both a political mistake and a human tragedy. Most of those people would have been living in that area for a long time. They work close by; their children go to nearby schools. If you uproot them from that environment and put them elsewhere they feel alienated; their work, education, and social life get disrupted. What Mr. Premadasa meant by slum clearance was improving the quality of life of slum dwellers by providing them with better housing and other basic facilities” (President Premadasa and I: Our Story).

A necessary aside: Grabbing these commercially valuable land by expelling the residents into the outskirts of the city was a key component of Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s Colombo Metropolitan Corporation plan. “The government is to demolish housing schemes constructed by former President Ranasinghe Premadasa, officials said,” (The Sunday Leader – 25.9.2011). The Supreme Court’s decision against the Sacred Areas Act compelled the abandonment of this plan. But the Rajapaksas were able to nullify another Premadasa initiative: making public sector recruitment mandatory on competitive exams – a recommendation of the Youth Commission of 1989. In 2007, Mahinda Rajapaksa issued a circular restoring recruitment via political patronage. When the JVP objected, Rajapaksa reportedly told them to provide their own lists (Lakbima News – 9.9.2007).

Radical in conception; conciliatory in implementation

There is a global tradition of developmental programmes which are (in the words of Amartya Sen) ‘good and just’. These are radical in intent but non-confrontational in style and regard economic strategy as a series of compromises balancing the interests of diverse socio-economic groups, for a common good. The Premadasa development projects belong in this category, expansive, yet grounded.

The 200 Garment Factories Programme was perhaps the best case in point. It amounted to a radical departure from the national and global norm of herding low-paid workers into specialised zones. Instead, entrepreneurs were encouraged – via loans and garment quotas – to set up factories in places where unemployment and poverty were rife. The state acted not as owner but as facilitator. The factories had to be new constructions, employ a minimum of 500 workers, pay a minimum wage of Rs 2000 plus meals, medical facilities etc. The success of the 200 Garment Factories Programme demonstrated that export-oriented and labour-friendly industrialisation was eminently possibly. An infamously exploitative industry (with sweatshop-type working-conditions) was transformed into its opposite, not through compulsion (let alone expropriation) but through persuasion (incentives). Development miracles are made on earth, via visions uncircumscribed by labels and political will.

Sirisena Cooray writes how in the at the Kataragama Gam Udawa, Premadasa built a common Buddhist-Hindu-Christian-Islamic place of worship symbolic of the ethno-religiously pluralist nature of Sri Lanka. “It was an interesting concept – you would come in together through a single entrance, branch out to go to different places of worship and once again gather together to go out. But the Buddhist monks opposed it; they did not like the idea” (President Premadasa and I: Our Story). It was another of Premadasa’s dream, a country where primordial differences would not lead to bloody divisions. “Sri Lanka has always had many ethnic groups, many religions and many social traditions… The history or the future of Sri Lanka does not belong to any group,” he said in 1990 and meant it. Lasting unity – be it national or social – could be built only by effecting tangible improvements in the living-conditions of all the poor, Sinhala, Tamil, and Muslim.

Giving everyone something to lose was the only true guarantee against societal violence and systemic instability, Premadasa believed. The rich and the poor, the majority and the minorities, all must be made to understand their need of and vulnerability to each other. In the urban housing schemes Premadasa built, flats were allocated via a pluralist policy. Every apartment block was representative of the larger Lankan nation, with Sinhala, Tamil and Muslim householders. During Black July, Colombo North and Central were spared the worst of violence thanks to this foresight. You could not set fire to your Tamil neighbour’s house without imperilling your own, not in some distant future, but in the next few minutes. Gulfs could be bridged most effectively not by stirring slogans or pious utterings, but by tangible acts: shelter, employment, a leg-up out of poverty. The old Premadasa programme may not be replicable in the new times, but his innovative approach remains timeless; and indispensable.

Features

US’ drastic aid cut to UN poses moral challenge to world

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

‘Adapt, shrink or die’ – thus runs the warning issued by the Trump administration to UN humanitarian agencies with brute insensitivity in the wake of its recent decision to drastically reduce to $2bn its humanitarian aid to the UN system. This is a substantial climb down from the $17bn the US usually provided to the UN for its humanitarian operations.

Considering that the US has hitherto been the UN’s biggest aid provider, it need hardly be said that the US decision would pose a daunting challenge to the UN’s humanitarian operations around the world. This would indeed mean that, among other things, people living in poverty and stifling material hardships, in particularly the Southern hemisphere, could dramatically increase. Coming on top of the US decision to bring to an end USAID operations, the poor of the world could be said to have been left to their devices as a consequence of these morally insensitive policy rethinks of the Trump administration.

Earlier, the UN had warned that it would be compelled to reduce its aid programs in the face of ‘the deepest funding cuts ever.’ In fact the UN is on record as requesting the world for $23bn for its 2026 aid operations.

If this UN appeal happens to go unheeded, the possibilities are that the UN would not be in a position to uphold the status it has hitherto held as the world’s foremost humanitarian aid provider. It would not be incorrect to state that a substantial part of the rationale for the UN’s existence could come in for questioning if its humanitarian identity is thus eroded.

Inherent in these developments is a challenge for those sections of the international community that wish to stand up and be counted as humanists and the ‘Conscience of the World.’ A responsibility is cast on them to not only keep the UN system going but to also ensure its increased efficiency as a humanitarian aid provider to particularly the poorest of the poor.

It is unfortunate that the US is increasingly opting for a position of international isolation. Such a policy position was adopted by it in the decades leading to World War Two and the consequences for the world as a result for this policy posture were most disquieting. For instance, it opened the door to the flourishing of dictatorial regimes in the West, such as that led by Adolph Hitler in Germany, which nearly paved the way for the subjugation of a good part of Europe by the Nazis.

If the US had not intervened militarily in the war on the side of the Allies, the West would have faced the distressing prospect of coming under the sway of the Nazis and as a result earned indefinite political and military repression. By entering World War Two the US helped to ward off these bleak outcomes and indeed helped the major democracies of Western Europe to hold their own and thrive against fascism and dictatorial rule.

Republican administrations in the US in particular have not proved the greatest defenders of democratic rule the world over, but by helping to keep the international power balance in favour of democracy and fundamental human rights they could keep under a tight leash fascism and linked anti-democratic forces even in contemporary times. Russia’s invasion and continued occupation of parts of Ukraine reminds us starkly that the democracy versus fascism battle is far from over.

Right now, the US needs to remain on the side of the rest of the West very firmly, lest fascism enjoys another unfettered lease of life through the absence of countervailing and substantial military and political power.

However, by reducing its financial support for the UN and backing away from sustaining its humanitarian programs the world over the US could be laying the ground work for an aggravation of poverty in the South in particular and its accompaniments, such as, political repression, runaway social discontent and anarchy.

What should not go unnoticed by the US is the fact that peace and social stability in the South and the flourishing of the same conditions in the global North are symbiotically linked, although not so apparent at first blush. For instance, if illegal migration from the South to the US is a major problem for the US today, it is because poor countries are not receiving development assistance from the UN system to the required degree. Such deprivation on the part of the South leads to aggravating social discontent in the latter and consequences such as illegal migratory movements from South to North.

Accordingly, it will be in the North’s best interests to ensure that the South is not deprived of sustained development assistance since the latter is an essential condition for social contentment and stable governance, which factors in turn would guard against the emergence of phenomena such as illegal migration.

Meanwhile, democratic sections of the rest of the world in particular need to consider it a matter of conscience to ensure the sustenance and flourishing of the UN system. To be sure, the UN system is considerably flawed but at present it could be called the most equitable and fair among international development organizations and the most far-flung one. Without it world poverty would have proved unmanageable along with the ills that come along with it.

Dehumanizing poverty is an indictment on humanity. It stands to reason that the world community should rally round the UN and ensure its survival lest the abomination which is poverty flourishes. In this undertaking the world needs to stand united. Ambiguities on this score could be self-defeating for the world community.

For example, all groupings of countries that could demonstrate economic muscle need to figure prominently in this initiative. One such grouping is BRICS. Inasmuch as the US and the West should shrug aside Realpolitik considerations in this enterprise, the same goes for organizations such as BRICS.

The arrival at the above international consensus would be greatly facilitated by stepped up dialogue among states on the continued importance of the UN system. Fresh efforts to speed-up UN reform would prove major catalysts in bringing about these positive changes as well. Also requiring to be shunned is the blind pursuit of narrow national interests.

Features

Egg white scene …

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

Hi! Great to be back after my Christmas break.

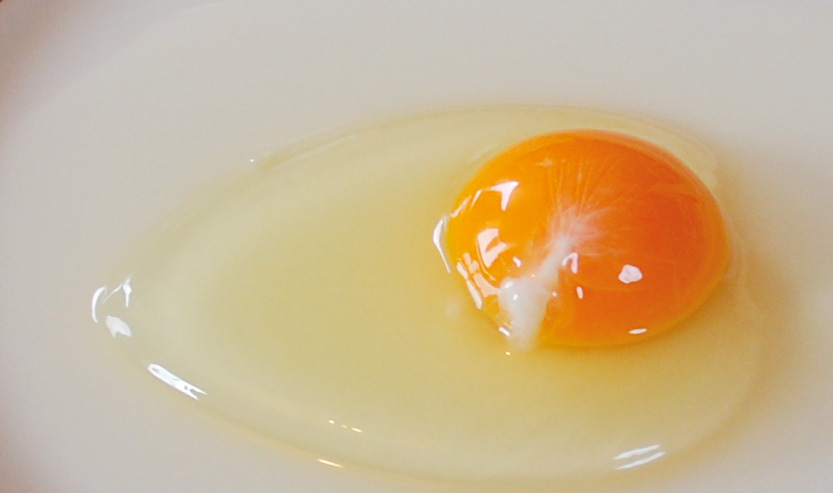

Thought of starting this week with egg white.

Yes, eggs are brimming with nutrients beneficial for your overall health and wellness, but did you know that eggs, especially the whites, are excellent for your complexion?

OK, if you have no idea about how to use egg whites for your face, read on.

Egg White, Lemon, Honey:

Separate the yolk from the egg white and add about a teaspoon of freshly squeezed lemon juice and about one and a half teaspoons of organic honey. Whisk all the ingredients together until they are mixed well.

Apply this mixture to your face and allow it to rest for about 15 minutes before cleansing your face with a gentle face wash.

Don’t forget to apply your favourite moisturiser, after using this face mask, to help seal in all the goodness.

Egg White, Avocado:

In a clean mixing bowl, start by mashing the avocado, until it turns into a soft, lump-free paste, and then add the whites of one egg, a teaspoon of yoghurt and mix everything together until it looks like a creamy paste.

Apply this mixture all over your face and neck area, and leave it on for about 20 to 30 minutes before washing it off with cold water and a gentle face wash.

Egg White, Cucumber, Yoghurt:

In a bowl, add one egg white, one teaspoon each of yoghurt, fresh cucumber juice and organic honey. Mix all the ingredients together until it forms a thick paste.

Apply this paste all over your face and neck area and leave it on for at least 20 minutes and then gently rinse off this face mask with lukewarm water and immediately follow it up with a gentle and nourishing moisturiser.

Egg White, Aloe Vera, Castor Oil:

To the egg white, add about a teaspoon each of aloe vera gel and castor oil and then mix all the ingredients together and apply it all over your face and neck area in a thin, even layer.

Leave it on for about 20 minutes and wash it off with a gentle face wash and some cold water. Follow it up with your favourite moisturiser.

Features

Confusion cropping up with Ne-Yo in the spotlight

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

Superlatives galore were used, especially on social media, to highlight R&B singer Ne-Yo’s trip to Sri Lanka: Global superstar Ne-Yo to perform live in Colombo this December; Ne-Yo concert puts Sri Lanka back on the global entertainment map; A global music sensation is coming to Sri Lanka … and there were lots more!

At an official press conference, held at a five-star venue, in Colombo, it was indicated that the gathering marked a defining moment for Sri Lanka’s entertainment industry as international R&B powerhouse and three-time Grammy Award winner Ne-Yo prepares to take the stage in Colombo this December.

What’s more, the occasion was graced by the presence of Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports & Youth Affairs of Sri Lanka, and Professor Ruwan Ranasinghe, Deputy Minister of Tourism, alongside distinguished dignitaries, sponsors, and members of the media.

According to reports, the concert had received the official endorsement of the Sri Lanka Tourism Promotion Bureau, recognising it as a flagship initiative in developing the country’s concert economy by attracting fans, and media, from all over South Asia.

However, I had that strange feeling that this concert would not become a reality, keeping in mind what happened to Nick Carter’s Colombo concert – cancelled at the very last moment.

Carter issued a video message announcing he had to return to the USA due to “unforeseen circumstances” and a “family emergency”.

Though “unforeseen circumstances” was the official reason provided by Carter and the local organisers, there was speculation that low ticket sales may also have been a factor in the cancellation.

Well, “Unforeseen Circumstances” has cropped up again!

In a brief statement, via social media, the organisers of the Ne-Yo concert said the decision was taken due to “unforeseen circumstances and factors beyond their control.”

Ne-Yo, too, subsequently made an announcement, citing “Unforeseen circumstances.”

The public has a right to know what these “unforeseen circumstances” are, and who is to be blamed – the organisers or Ne-Yo!

Ne-Yo’s management certainly need to come out with the truth.

However, those who are aware of some of the happenings in the setup here put it down to poor ticket sales, mentioning that the tickets for the concert, and a meet-and-greet event, were exorbitantly high, considering that Ne-Yo is not a current mega star.

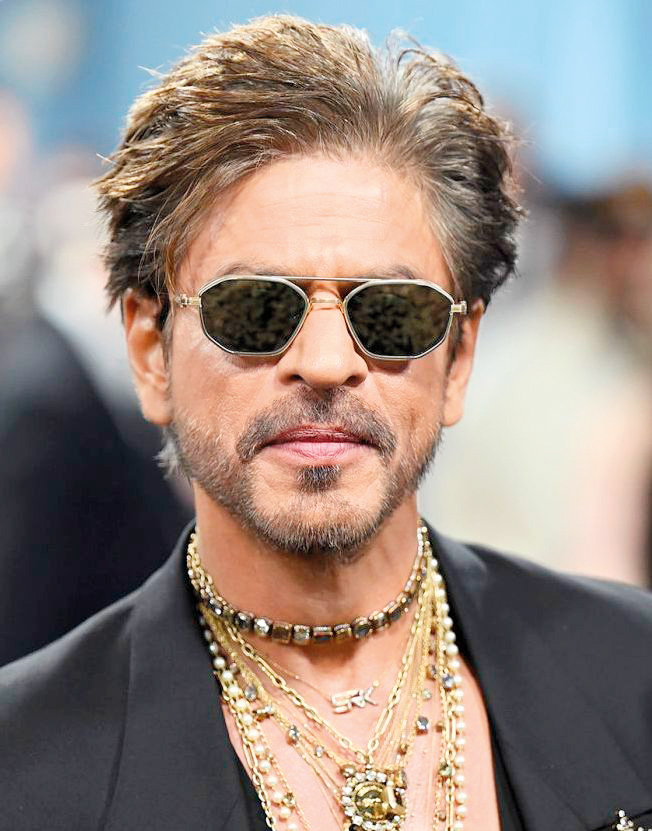

We also had a cancellation coming our way from Shah Rukh Khan, who was scheduled to visit Sri Lanka for the City of Dreams resort launch, and then this was received: “Unfortunately due to unforeseen personal reasons beyond his control, Mr. Khan is no longer able to attend.”

Referring to this kind of mess up, a leading showbiz personality said that it will only make people reluctant to buy their tickets, online.

“Tickets will go mostly at the gate and it will be very bad for the industry,” he added.

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRethinking post-disaster urban planning: Lessons from Peradeniya

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoAre we reading the sky wrong?