Features

Disce aut Discede

by Gamini Seneviratne

Form-mates, classmates perhaps in Mr. J E V Pieris’s IA, I seem to recall also the ‘J’ in J Godwin Perera. His reminiscences of those times past are indeed welcome. What follows here are some additions / amendments.

Given the heading used by Godwin and repeated here, the first of them must surely be the third option that completes that quote: Caedi (be caned). Looking back from present times, a very mild option, one would say. I was caned only once, by Mr. Bob Edwards: he had forgotten what my supposed misdemeanor was and I couldn’t tell him why I was there as I had ceased to know what it was.

Godwin’s mentioned the Senior Lit. and the Best Speaker’s prize. I was never involved in the first and had a spectacular spell at the second. I forget what the subject was but the Principal’s hand had been hovering over the bell as I passed the time limit. The judge was A B Perera, a Barrister who had served as Principal of Ananda and was to serve as our Ambassador to China. In his summing up he said that I had made a very interesting speech – but rules must be observed. He awarded the prize to Mark (L J M) Cooray who had elocuted his forgettable words finishing on the dot. (He went on to obtain all the postgraduate degrees required for a career as an academic. A high point in that was his attempt to prove that the indigenous people Down Under who had built their culture through some 40,000 years “had no right to the land”. There would have been some applause in academe.)

L H Meegama had a bicycle and some days when I didn’t join another gang up Buller’s road to Galle road I went with Meeya to his place on Vajira road. Our Mahappa’s place on Janaki Lane was almost directly across Galle road from there. His senior sister would sometimes be in the kitchen cooking – scraping coconut and such – while her fiancée chatted with her. He took up engineering and I last heard was working in the Port when he died relatively young.

And so did Tyrell Muttiah, superlative scrum-half, who lived on Galle road just by Bin Ahmed’s studio at the top of Janaki Lane. He seemed to have been born smiling and bred in courtesy. He was the most pleasant of friends.

K. Manickavasagar, Manicks, and I were immediate, next-door neighbors but we were not together in Form I A. He went into the pharmaceutical industry and headed Pfizer here before retiring to Canada.

Am sure have missed many in that class. I have asked as many of that Group of ‘Forty Nine as I could locate here: their memory, alas, is as bad as mine.

May we all make a good ending!

In that class chaired by Mr. Nathanielsz, aka “Naetta”, Mr Pieris, aka “Bada” was the presiding deity. His approval took the form of “Mr. Mendis, you are a little gentleman.” Surprising as it may be and far less often than “Mr. Mendis” though it was, he is known to have waved the wand over “Mr. Seneviratne”.

“Mr. Mendis” was Lalith, one in the cluster a few of us occupied. Among the others in it were Chulani Wickremasinghe, Laki Senanayake and Punyadasa Edussuriya. Perhaps Tyrell Mutthiah was in it too.

Of those in the periphery, a failing memory prompts the names – Nimal Fonseka, Wonkie de Silva, P S C Goonatileke, L H Meegama and H C Wickremesinghe.

I present a few notes on that lot.

Lalith was an artist and he sketched a good bit of the time. As a medical doctor he took to the study of filaria and headed that field of research. When he became Director of Medical Services and I saw him there it struck me that he was in the wrong place: he was not built to deal with politicians especially not those in the Department of Health. I suggested that he gets back to his research in an area in which he had already distinguished himself but he passed that with the sweet smile that characterized him.

Laki too did pencil sketches but they were mostly copies of figures, including horses, from the ‘western comics’. Among his skills was the pea shooter and we had exhibitions when Naetta chose to lay his head on his arm and say, “Read”! One after the other we ‘read’ and Naetta awarded marks with his free hand. There were quite a number of zeros and he couldn’t signal any more than five. Laki took aim and sent a spit-ball straight as an arrow to the bald spot on Naetta’s crown.

He took his artistic skills to Dambulla where he sold his drawings, signed kali, to tourists. Laki was and is casual about things. When, on my way to Jaffna, I dropped by to see him at Diyabubula, he had a high fever and looked quite ill. He had obtained medication from the Dambulla Hospital, he said, as he coughed out a typically c & b story – and was sharing the pills with workers who showed the same or similar symptoms. He had been ordered bed-rest and he had complied, he said, by lying flat in his jeep as it juddered around the jungle. A mutual friend, Chandra Subasinghe, lived not many miles away by the Dambulu Oya and managed to get the patient to the Matale Hospital ‘just-in-time’. (Chandra was quite as inventive as Laki and had informed the water-tax collectors from the Mahaweli that for many years his pumps had been accustomed to pumping water from the Dambulu Oya and would continue to do so. If those gentlemen had sent down water there from the Mahaweli and the Sudu Ganga, his pumps knew nothing about that).

Two desks away was Chulani who had the most inclusive collection of westerns – the Gene Autry, Roy Rogers, Lone Ranger, Tom Mix & co. freely available to us all. Such knowledge was not prescribed for us at school and Chula suffered a ‘take down’. He made up for it by topping the City & Guilds exams , migrating out there and on to the USA and thence to South America where, by his account, he out-samba’d all the experts that Rio could gather.

Punya Edussuriya’s father and mine had been at Ananda around the same time; Punya claimed that his father would have taught mine. That is unlikely – (I didn’t know it at the time, but my father had won the Senior English Essay prize in 1923 and his father could not have been that much his senior). They sat together in the pavilion at the Royal Thomian. In our first year we were among dozens of boys who encroached into the Oval grounds as the match neared its end. The boundary rope moved up or down and when Bradman Weerakoon was given out caught, Wignarajah the fielder was behind us and well behind the boundary line. We were right there and yelled that it was a six. Nobody listened. Years later when I mentioned it to Bradman he was unaware that he and St. Thomas’ had so been denied a right royal victory. Not the first time it happened and won’t be the last: the evidence of eyewitnesses is swept under, justice given no opening at all. Happens all the time.

Not many years later Punya and big brother Piyasiri were moved across to Ananda – a school that figured prominently in our family. Beginning with mother’s maternal uncle D B Jayatilaka’s contributions at the start, all our male relatives ‘on both sides’ as they say had been at Ananda: my father and his brothers, mother’s brothers, all our cousins. I was the ‘out’ chap and it happened like this. At the same time as I qualified to enter Royal I had been awarded the ‘Entrance Scholarship’ for Ananda – creating sort of competing claims. Regardless of having served on the academic staff at Ananda in the early 1900s father’s eldest brother had said, “Royal”! – after all he lived in Bambalapitiya and could keep an eye on me. That was convenient, a convenient story, but as the old man had told me the previous year (when I was a little over 9) he was disappointed in his sons.

That was the product of another pressure point. Our paternal grandmother had a cousin called Arthur Wijewardena; we had nothing to do with him but Mahappa had been in touch. All I remember is that he was an unsmiling kind of man who lived down Vajira Road next to Visakha; it had a nice garden and there was a son who sort of floated in and out of the verandah and drawing room offering biscuits. What was pertinent at the time was that he had been our Chief Justice and Mahappa had expected his sons to take to the law likewise as he himself had done. But what did they go and do? – One became an engineer on diesel locomotives and went on to become a chemical engineer (he built and ran Kelani Valley Canneries our best fruit processing factory) and the other an architect who also played piano, painted, sculpted and would you believe it? did ballet dancing. I was sort of the last chance to get the law back into his half of the family. I was to prove a disappointment too, but no one suspected it at the time.

In later years, though not for long, I made my peace with Ananda when Principal S A Wijetilleke recruited me as an English teacher. There I was to establish a friendship with V Thanabalasingham, the senior in that field, that continued as circumstances permitted through the rest of his life. Mr. Thanabalasingham’s intellectual acumen was quite on par with that of B St. E de Bruin or S Constantine at Royal. I had come to know of him earlier when, following the communal riots of 1958, my cousin, Asoka Gunasekara, wrote a short story around Thane’s experiences of those days; titled vibhagaya it was one of the best bodies of writing in Sinhala. In later years, when I mentioned vibhagaya those who had read the Kelani University literary magazine, Vimansa, assumed I was referring to a short story of mine in it that had the same title [that had to do with an actual vibhagaya, the government’s ‘efficiency bar’ exams.]

Before I continue, a brief note on the Royal Post Primary to which boys who failed to go over from Royal Prep were sent. There they were expected to adjust their focus more towards studies and away from, say, sports. One of them that year was Brindley Perera, generally regarded as the most gifted 10 year old batsman in our schools. (His nephew, Brendon Kuruppu, gave hints of how strong the genes were). Most of those who slipped at that point showed their caliber in later life. Those I recall include Susantha Samaranayake, the first Lankan to be appointed a Director / Manager at IBM; Dharmasiri Pieris, who had a distinguished career in the public sector including that of Secretary to the Prime Minister; and Sarath Weerasooria, Chairman of FINCO. My brother had moved there from Ananda and had the distinction, besides scoring a near-double century versus Carey, of being the first (only) – student to pass the SSC in the first year that Thurstan students were presented for that exam. He moved back to De Mazenod where he ended with a flourish as Senior Champion at athletics, Captain of cricket and winner of the General Proficiency prize. The police grabbed him then – and a young lawyer grabbed his girlfriend, much the prettiest schoolgirl seen at our railway station. I had written poems to her on his behalf and delivered them as she took a detour down Janaki lane where I lived on her way from the HFC to the railway station.

In the lot who got to Royal College that year (1949), 35, fully one-third, were from schools other than Royal Prep. Perhaps that accounts for the special distinction which seems to have marked that batch.

Even among 10 year-olds, Nimal / Nimma stood out for being pugnacious but was never a bully. He turned his hands to several part-time occupations at one of which, the Hotel De Universe’ he employed school friend Raja (Rahula) Silva when the then government failed to do him justice. When Raja fell asleep at wrong time of night Nimma functioned as bouncer at his hotel bar. An expatriate in England of long standing Nimma became a teetotaler I presume in mid-life: when he took leave of his business and related activities he was in great demand at parties – for drive-home services. “They get cocked and talk cock” he said, “so I stopped going for parties”. He continues his interest in topology and is last known to have remained more or less certifiably sane.

W K N Silva was a Proprietary Planter with tea and rubber in the Ratnapura district. I believe that two of his sisters married a pair of brothers. In his latter days he took exception to being called “Wonkie”; he said it should have been applied to Nalin (WNK) Fernando, journalist, because the name fitted him, initials and all. He had a sufficient number of siblings to retain the bulk of their estate after Land Reform.

Occasionally initials provided a convenient name – say, Jabba for JB. Susantha Goonatileke’s PSC was tempting and tempted. He chose engineering as did his cousin C L V Jayatileke (who proceeded all the way in mechanical engineering) but he took his BSc (Eng) and changed course towards the social sciences. It was a move that opened a range of intellectual challenges for him and brought his academic work into discussion at fora around the world. His son is perhaps way and away the wealthiest among us in the next generation.

H C (Channa) Wickremasinghe was one of the brightest among us but health-related hiccups prevented his full development as a scholar. Turner, his architect brother was a left arm spinner of a most mean disposition who played for Royal. Channa was content to send down mostly friendly off breaks of which he had a good opinion.

Godwin relates an incident concerning our ruggerites et al and he attributes the report on it to Mr. Orloff, Principal of Trinity College. As I recall, the Trinity Principal at the time was a Mr Walters and the incident had occurred not in a room at the Trinity hostel but on the train down from Kandy. However that may have been punishment was meted out as Godwin says. I was co-editor with Nihal Jayawickrema of the school magazine and inserted some quotes in the space for footnotes: one and all pointed towards the merits of forgiveness.

The Principal, Mr. Dudley K G de Silva, sent for me. I was met at his door by Mr. Elmo de Bruin who served as Manager of the Magazine. When the Principal saw that I was not without back-up he asked Mr. Bruin whether he had approved the insertions and he replied, “I have the fullest confidence in their judgment, Sir” spreading the blame.

Principal de Silva tended to take the word of fellow Principals a bit uncritically. I noticed that the Thomian magazine that year had carried a poem published some years previously in ours and wrote a little note to the Thomian editor, Ranjith Wijewardena, ribbing him about it. Instead of writing back in similar vein Ranjith had taken my note to his Warden – who had promptly phoned our Principal. Predictably I was sent for. As the fates decreed, I ran into Bruno on my way there. He heard me out and strolled into the Principal’s office ahead of me. He asked me to show the evidence to the Principal and suggested that “if ‘these Thomians’ had any sense they could have said they don’t retain past copies of our Magazine”! Writing from Jamaica a life-time later, Bruno recalled such and other ‘happenings’ of his years at Royal. There must be hundreds still around who miss him.

Features

Ranking public services with AI — A roadmap to reviving institutions like SriLankan Airlines

Efficacy measures an organisation’s capacity to achieve its mission and intended outcomes under planned or optimal conditions. It differs from efficiency, which focuses on achieving objectives with minimal resources, and effectiveness, which evaluates results in real-world conditions. Today, modern AI tools, using publicly available data, enable objective assessment of the efficacy of Sri Lanka’s government institutions.

Among key public bodies, the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka emerges as the most efficacious, outperforming the Department of Inland Revenue, Sri Lanka Customs, the Election Commission, and Parliament. In the financial and regulatory sector, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) ranks highest, ahead of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Public Utilities Commission, the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission, the Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the Sri Lanka Standards Institution.

Among state-owned enterprises, the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) leads in efficacy, followed by Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank. Other institutions assessed included the State Pharmaceuticals Corporation, the National Water Supply and Drainage Board, the Ceylon Electricity Board, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, and the Sri Lanka Transport Board. At the lower end of the spectrum were Lanka Sathosa and Sri Lankan Airlines, highlighting a critical challenge for the national economy.

Sri Lankan Airlines, consistently ranked at the bottom, has long been a financial drain. Despite successive governments’ reform attempts, sustainable solutions remain elusive.

Globally, the most profitable airlines operate as highly integrated, technology-enabled ecosystems rather than as fragmented departments. Operations, finance, fleet management, route planning, engineering, marketing, and customer service are closely coordinated, sharing real-time data to maximise efficiency, safety, and profitability.

The challenge for Sri Lankan Airlines is structural. Its operations are fragmented, overly hierarchical, and poorly aligned. Simply replacing the CEO or senior leadership will not address these deep-seated weaknesses. What the airline needs is a cohesive, integrated organisational ecosystem that leverages technology for cross-functional planning and real-time decision-making.

The government must urgently consider restructuring Sri Lankan Airlines to encourage:

=Joint planning across operational divisions

=Data-driven, evidence-based decision-making

=Continuous cross-functional consultation

=Collaborative strategic decisions on route rationalisation, fleet renewal, partnerships, and cost management, rather than exclusive top-down mandates

Sustainable reform requires systemic change. Without modernised organisational structures, stronger accountability, and aligned incentives across divisions, financial recovery will remain out of reach. An integrated, performance-oriented model offers the most realistic path to operational efficiency and long-term viability.

Reforming loss-making institutions like Sri Lankan Airlines is not merely a matter of leadership change — it is a structural overhaul essential to ensuring these entities contribute productively to the national economy rather than remain perpetual burdens.

By Chula Goonasekera – Citizen Analyst

Features

Why Pi Day?

International Day of Mathematics falls tomorrow

The approximate value of Pi (π) is 3.14 in mathematics. Therefore, the day 14 March is celebrated as the Pi Day. In 2019, UNESCO proclaimed 14 March as the International Day of Mathematics.

Ancient Babylonians and Egyptians figured out that the circumference of a circle is slightly more than three times its diameter. But they could not come up with an exact value for this ratio although they knew that it is a constant. This constant was later named as π which is a letter in the Greek alphabet.

It was the Greek mathematician Archimedes (250 BC) who was able to find an upper bound and a lower bound for this constant. He drew a circle of diameter one unit and drew hexagons inside and outside the circle such that the sides of each hexagon touch the sides of the circle. In mathematics the circle passing through all vertices of a polygon is called a ‘circumcircle’ and the largest circle that fits inside a polygon tangent to all its sides is called an ‘incircle’. The total length of the smaller hexagon then becomes the lower bound of π and the length of the hexagon outside the circle is the upper bound. He realised that by increasing the number of sides of the polygon can make the bounds get closer to the value of Pi and increased the number of sides to 12,24,48 and 60. He argued that by increasing the number of sides will ultimately result in obtaining the original circle, thereby laying the foundation for the theory of limits. He ended up with the lower bound as 22/7 and the upper bound 223/71. He could not continue his research as his hometown Syracuse was invaded by Romans and was killed by one of the soldiers. His last words were ‘do not disturb my circles’, perhaps a reference to his continuing efforts to find the value of π to a greater accuracy.

Archimedes can be considered as the father of geometry. His contributions revolutionised geometry and his methods anticipated integral calculus. He invented the pulley and the hydraulic screw for drawing water from a well. He also discovered the law of hydrostatics. He formulated the law of levers which states that a smaller weight placed farther from a pivot can balance a much heavier weight closer to it. He famously said “Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the earth”.

Mathematicians have found many expressions for π as a sum of infinite series that converge to its value. One such famous series is the Leibniz Series found in 1674 by the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, which is given below.

π = 4 ( 1 – 1/3 + 1/5 – 1/7 + 1/9 – ………….)

The Indian mathematical genius Ramanujan came up with a magnificent formula in 1910. The short form of the formula is as follows.

π = 9801/(1103 √8)

For practical applications an approximation is sufficient. Even NASA uses only the approximation 3.141592653589793 for its interplanetary navigation calculations.

It is not just an interesting and curious number. It is used for calculations in navigation, encryption, space exploration, video game development and even in medicine. As π is fundamental to spherical geometry, it is at the heart of positioning systems in GPS navigations. It also contributes significantly to cybersecurity. As it is an irrational number it is an excellent foundation for generating randomness required in encryption and securing communications. In the medical field, it helps to calculate blood flow rates and pressure differentials. In diagnostic tools such as CT scans and MRI, pi is an important component in mathematical algorithms and signal processing techniques.

This elegant, never-ending number demonstrates how mathematics transforms into practical applications that shape our world. The possibilities of what it can do are infinite as the number itself. It has become a symbol of beauty and complexity in mathematics. “It matters little who first arrives at an idea, rather what is significant is how far that idea can go.” said Sophie Germain.

Mathematics fans are intrigued by this irrational number and attempt to calculate it as far as they can. In March 2022, Emma Haruka Iwao of Japan calculated it to 100 trillion decimal places in Google Cloud. It had taken 157 days. The Guinness World Record for reciting the number from memory is held by Rajveer Meena of India for 70000 decimal places over 10 hours.

Happy Pi Day!

The author is a senior examiner of the International Baccalaureate in the UK and an educational consultant at the Overseas School of Colombo.

by R N A de Silva

Features

Sheer rise of Realpolitik making the world see the brink

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

As matters stand, there seems to be no credible evidence that the Indian state was aware of the impending torpedoing of the Iranian vessel but these acerbic-tongued politicians of Sri Lanka’s South would have the local public believe that the tragedy was triggered with India’s connivance. Likewise, India is accused of ‘embroiling’ Sri Lanka in the incident on account of seemingly having prior knowledge of it and not warning Sri Lanka about the impending disaster.

It is plain that a process is once again afoot to raise anti-India hysteria in Sri Lanka. An obligation is cast on the Sri Lankan government to ensure that incendiary speculation of the above kind is defeated and India-Sri Lanka relations are prevented from being in any way harmed. Proactive measures are needed by the Sri Lankan government and well meaning quarters to ensure that public discourse in such matters have a factual and rational basis. ‘Knowledge gaps’ could prove hazardous.

Meanwhile, there could be no doubt that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty was violated by the US because the sinking of the Iranian vessel took place in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While there is no international decrying of the incident, and this is to be regretted, Sri Lanka’s helplessness and small player status would enable the US to ‘get away with it’.

Could anything be done by the international community to hold the US to account over the act of lawlessness in question? None is the answer at present. This is because in the current ‘Global Disorder’ major powers could commit the gravest international irregularities with impunity. As the threadbare cliché declares, ‘Might is Right’….. or so it seems.

Unfortunately, the UN could only merely verbally denounce any violations of International Law by the world’s foremost powers. It cannot use countervailing force against violators of the law, for example, on account of the divided nature of the UN Security Council, whose permanent members have shown incapability of seeing eye-to-eye on grave matters relating to International Law and order over the decades.

The foregoing considerations could force the conclusion on uncritical sections that Political Realism or Realpolitik has won out in the end. A basic premise of the school of thought known as Political Realism is that power or force wielded by states and international actors determine the shape, direction and substance of international relations. This school stands in marked contrast to political idealists who essentially proclaim that moral norms and values determine the nature of local and international politics.

While, British political scientist Thomas Hobbes, for instance, was a proponent of Political Realism, political idealism has its roots in the teachings of Socrates, Plato and latterly Friedrich Hegel of Germany, to name just few such notables.

On the face of it, therefore, there is no getting way from the conclusion that coercive force is the deciding factor in international politics. If this were not so, US President Donald Trump in collaboration with Israeli Rightist Premier Benjamin Natanyahu could not have wielded the ‘big stick’, so to speak, on Iran, killed its Supreme Head of State, terrorized the Iranian public and gone ‘scot-free’. That is, currently, the US’ impunity seems to be limitless.

Moreover, the evidence is that the Western bloc is reuniting in the face of Iran’s threats to stymie the flow of oil from West Asia to the rest of the world. The recent G7 summit witnessed a coming together of the foremost powers of the global North to ensure that the West does not suffer grave negative consequences from any future blocking of western oil supplies.

Meanwhile, Israel is having a ‘free run’ of the Middle East, so to speak, picking out perceived adversarial powers, such as Lebanon, and militarily neutralizing them; once again with impunity. On the other hand, Iran has been bringing under assault, with no questions asked, Gulf states that are seen as allying with the US and Israel. West Asia is facing a compounded crisis and International Law seems to be helplessly silent.

Wittingly or unwittingly, matters at the heart of International Law and peace are being obfuscated by some pro-Trump administration commentators meanwhile. For example, retired US Navy Captain Brent Sadler has cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides for the right to self or collective self-defence of UN member states in the face of armed attacks, as justifying the US sinking of the Iranian vessel (See page 2 of The Island of March 10, 2026). But the Article makes it clear that such measures could be resorted to by UN members only ‘ if an armed attack occurs’ against them and under no other circumstances. But no such thing happened in the incident in question and the US acted under a sheer threat perception.

Clearly, the US has violated the Article through its action and has once again demonstrated its tendency to arbitrarily use military might. The general drift of Sadler’s thinking is that in the face of pressing national priorities, obligations of a state under International Law could be side-stepped. This is a sure recipe for international anarchy because in such a policy environment states could pursue their national interests, irrespective of their merits, disregarding in the process their obligations towards the international community.

Moreover, Article 51 repeatedly reiterates the authority of the UN Security Council and the obligation of those states that act in self-defence to report to the Council and be guided by it. Sadler, therefore, could be said to have cited the Article very selectively, whereas, right along member states’ commitments to the UNSC are stressed.

However, it is beyond doubt that international anarchy has strengthened its grip over the world. While the US set destabilizing precedents after the crumbling of the Cold War that paved the way for the current anarchic situation, Russia further aggravated these degenerative trends through its invasion of Ukraine. Stepping back from anarchy has thus emerged as the prime challenge for the world community.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoWinds of Change:Geopolitics at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoProf. Dunusinghe warns Lanka at serious risk due to ME war

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoRoyal start favourites in historic Battle of the Blues

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoThe 147th Royal–Thomian and 175 Years of the School by the Sea

-

News2 days ago

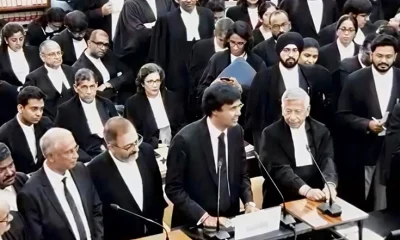

News2 days agoHistoric address by BASL President at the Supreme Court of India

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoCEBEU warns of operational disruptions amid uncertainty over CEB restructuring

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoSeven decades of sartorial excellence: The legacy of Linton Master Tailors in Kandy