Features

What JVP-NPP needs to do to win

By Dr. DAYAN JAYATILLEKA

A young academic at the Open University writing on a popular website has recently defined the NPP project as ‘Left populist’, a term which is very familiar to us at least from the writings of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. He also mentions several parallels and precursors internationally.

As one who has been advocating a ‘left populist’ project for years, I am disinclined to nit-pick about whether or not the JVP-NPP fits the bill. At the moment and in its current incarnation, it is indeed the closest we have to a ‘left populist’ project. Its competitor the SJB, which its founder-leader identifies as social democratic, would be as approximate –and as loose– a fit for the labels ‘progressive populist’, ‘moderate populist’ or ‘populist centrist’, as the JVP-NPP is for ‘left populist’. But that’s the deck of cards we have.

The points I seek to make are different, and may be said to boil down to a single theme or problematique.

Distorted Left Populism

My argument is that the JVP-NPP is as distant from ‘left populism’ globally as it was from ‘left revolutionism’ globally in an earlier incarnation. In both avatars, it is unique in its leftism but not in a positive or helpful way for its cause at any given time.

Mine is not intended as a damning indictment of the JVP-NPP. It is intended as a constructive criticism of a rectifiable error, the rectification of which is utterly urgent given the deadly threat posed by the Wickremesinghe administration and its project of dependent dictatorship.

The JVP-NPP has a structural absence that no ‘left populist’ enterprise, especially in Latin America, has ever had. It is an absence that has marked the JVP from its inception and has been carried over into the present NPP project.

It is not an absence unique to the JVP but figures more in Sri Lanka than it has almost anywhere else. I say this because the same ‘absence’ characterised the LTTE as well. In short, that factor or its radical absence has marred the anti-systemic forces of South and North on the island.

The homeland of left populism has been Latin America while its second home has been Southern Europe. With the exception of Greece, it may be said that ‘left populism’ has an Ibero-American or culturally Hispanic character, which some might trace to the ‘romanticism’ of that culture. But such considerations need not detain us here.

‘Left populism’ has had several identifiable sources and points of departure: the former guerrilla movements of the 1960s and 1970s; the non-guerrilla movements of resistance to dictatorships; parties and split-offs from parties of the Marxist left; left-oriented split-offs or the leftwing of broad flexible even centrist populist formations; leftwing experiments from within the militaries etc.

Populism, Pluralism & Unity

Despite this diversity, all experiments of a Left populist character in Latin America and Europe, have had one thing in common: various forms of unity – e.g., united fronts, blocs etc.—of political parties. I would take up far too much space if I were to list them, starting with the Frente Amplio (which means precisely ‘Broad Front’) initiated by the Tupamaros-MLN of Uruguay and containing the Uruguayan Communist party and headed by a military man, General Liber Seregni, in 1970. The Frente Amplio lasted through the decades of the darkest civil-military dictatorship up to the presidential electoral victories of Tabaré Vasquez and Mujica respectively. Another example would be El Salvador’s FMLN, which brought together several Marxist guerrilla movements into a single front under the stern insistence of Fidel Castro.

Though the roots of unity were back in the 1970s, the formula has only been strengthened in the 1990s and 21st century projects of Left populism. There is a theoretical-strategic logic for this. The polarisation of ‘us vs them’, the 99% vs. the 1%, the many not the few—in socioeconomic terms—is of course a hallmark of populism. But pro-NPP academics and ideologues are unaware of or omit its corollary everywhere from Uruguay to Greece and Spain. Namely, that socioeconomic ‘majoritarianism’ is not possible with a single party as agency.

When the JVP and the NPP have the same leader, and the JVP leader was the founder of the NPP, I cannot regard it as a truly autonomous project, but a party project. Left populism globally, from its inception right up to Lula last year, is predicated on the admission of political, not just social plurality, and the fact that socioeconomic, i.e., popular majoritarianism is possible only as a pluri-party united front, platform or bloc.

This recognition of the imperative of unity as necessitating a convergence of political fractions and currents; that unity is impossible as a function of a single political party; that authentic majoritarianism i.e., “us” is possible only if “we” converge and combine as an ensemble of our organic political agencies, is a structural feature of Left Populism.

It is radically absent in the JVP-NPP and has been so from the JVP’s founding in 1965. It was also true of the LTTE.

It is this insistence on political unipolarity (to put it diplomatically) or political monopoly (to put it bluntly) is a genetic defect of the JVP which has been carried over into the NPP project.

I do not say this to contest the leading role and the main role that the JVP has earned in any left populist project. I say it to draw the Gramscian distinction between ‘leadership’ and ‘domination’. Only ‘leadership’ can create consensus and popular consent; domination through monopoly cannot.

The simple truth is that however ‘left populist’ you think you are; no single party can be said to represent the people or even a majority – as distinct from a mere plurality– of the people. Furthermore, the people are not a unitary subject, and therefore cannot have a unitary leadership. This is the importance of Fidel Castro’s insistence to the Latin American Left of a ‘united command’ which brings together the diverse segments of the left by reflecting plurality.

Anyone who knows the history of Syriza and Podemos knows that they are not outcrops of some single party of long-standing but the result of an organic process of convergences of factions.

Had the JVP had a policy of united fronts – within the Southern left and with the Northern left– it would not have been as decisively defeated as it was in its two insurrections, and might have even succeeded in its second attempt. Though it has formed the NPP which has brought some significant success, it is still POLITICALLY sectarian in that it has no political alliances, partnerships, i.e., NO POLITICAL RELATIONSHIPS outside of itself.

I must emphasize that here I am not speaking of a bloc with the SJB, though it is most desirable, to be recommended, and if this were Latin America would definitely be on the agenda of discussion.

Post-Aragalaya Left

Let us speak frankly. The most important phenomenon of recent times (since the victorious end of the war) was the Aragalaya of last year. The JVP, especially its student front the SYU, participated in that massive uprising which dislodged President Gotabaya Rajapaksa, but it played a less decisive role in the Aragalaya than did the FSP and the IUSF which is close to it. This is by no means to say that the FSP led the Aragalaya, but to point out that it played a more decisive role – which included some mistakes– than did the JVP.

How then does one remain blind to the fact that the JVP-NPP’s ‘left populism’ does not include the FSP and by extension the IUSF? How can there be a ‘popular bloc’ – a key element of left populism—without the IUSF?

Given that Pubudu Jayagoda, Duminda Nagamuwa, Lahiru Weerasekara and Wasantha Mudalige are among the most successful public communicators today (especially on the left), what kind of ‘left’ is a ‘left populism’ devoid of their presence, participation and contribution?

What does it take to recognise that unity of some sort of these two streams of the Left could result in a most useful division of labour and a quantum leap in the hopes and morale of the increasingly left-oriented post-Aragalaya populace, especially the youth?

Surely the very sight of a platform with the leaders of the JVP-NPP and the FSP-IUSF (AKD and Kumar Gunaratnam, Eranga Gunasekara and Wasantha Mudalige, Wasantha Samarasinghe and Duminda Nagamuwa, Bimal Ratnayake and Pubudu Jayagoda) will take the Left populist project to the next level?

As a party the JVP from its birth, and by extension, the NPP today, have set aside one of the main weapons of leftist theory, strategy and political practice: the United Front. Lenin, Trotsky, Stalin, Dimitrov, Gramsci, Togliatti, Ho Chi Minh, Mao Zedong and Fidel Castro have founded and enriched this strategic concept.

It is difficult to accept that Rohana Wijeweera and Anura Kumara Dissanayake knew/know better than these giants, and that the JVP-NPP can dispense with this political sword and shield and yet prevail–or even survive the coming storm.

The JVP must present a LEFT option in the leadership of which is the major shareholder; not merely a JVP option or para-JVP option, which is what the NPP is. A credible, viable Left alternative cannot be reduced to a single party and its front/auxiliary; it cannot but be a United Left – a Left Front– alternative.

***********************

[Dr Dayan Jayatilleka is author of The Great Gramsci: Imagining an Alt-Left Project, in ‘On Public Imagination: A Political & Ethical Imperative’ eds Richard Falk et al, Routledge, New York, 2019.]

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Features7 days ago

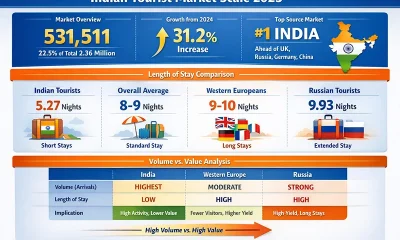

Features7 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoFuture must be won

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository