Features

THE WORLD HERITAGE SITES OF SRI LANKA

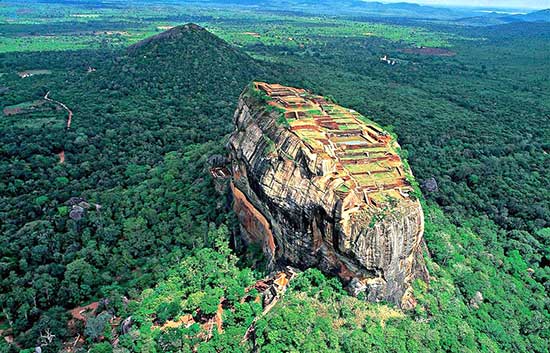

SIGIRIYA – THE CITADEL IN THE SKY

By Everyman

From patricide to a palace. From intrigue to ignominy. From paintings to poems. From pleasure gardens to a playboy king. Sigiriya has it all. Archaeology, history, controversy and folklore are entwined and enmeshed in the unfolding of the story of Sigiriya. Sigiriya or ‘Sinhagiri‘ – ‘Lion Rock’ derives its name from the huge rock carved lion located on a small plateau on the Northern side of the rock. Over the decades the top part of this lion has fallen apart and today only the two mammoth front paws are visible forming an entrance between them. The rock itself is the remains of hardened lava which would have pushed through the ground surface causing a volcanic eruption. According to geologists this could have happened over two billion years ago. Around Sigiriya there still can be seen numerous granite boulders which are also remains of the lava that formed Sigiriya. With the recent passing away of Prince Phillip, Duke of Edinburgh it may interest readers to know that one of the most famous lava created rocks is in Edinburgh , capital of Scotland. On top of this rock lies the magnificent Edinburgh Castle, built in 1103 In 1831 a British Army Major, Jonathan Forbes while riding on horseback through the country stumbled on Sigiriya which was amongst the jungles and scrub land of the Matale District. And for the first time the Western world, in particular Britain, under whom Ceylon (as it was then known ) was a colony, came to know about Sigiriya. In the 1890’s the first extensive archeological excavation on Sigiriya was done by the Archeological Commissioner, H.C.P. Bell who was appointed by the British Governor, Sir Arthur Gordon. Later on in 1982, full scale archeological excavations to restore Sigiriya began through the Sri Lankan Government funded Cultural Triangle Programme. It was in that year that Sigiriya was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage Site lists. Also inscribed were The Ancient City of Polonnaruwa and the Sacred City of Anuradhapura. These three sites were the first in Sri Lanka to gain this distinction. However within the pages our own ancient chronical the ‘Culavamsa’, the story of Sigiriya can be traced. Actually the story of Sigiriya commences with the reign of King Dhatusena. Having defeated the Pandyan invaders he was crowned King of Sri Lanka in 549 CE and ruled from Anuradhapura. Despite his fame for developing agriculture and thereby meeting the needs of the people by constructing 18 irrigation tanks, he also performed his kingly duties as a devout Buddhist by erecting the now famous 43 ft tall Avukana statue of Lord Buddha.

Yet, King Dhatusena had a streak of cruelty. Migara the chief of the King’s army was married to King Dhatusena’s favourite daughter. While his mother was King Dhatusena’s sister. In all probability it was due to this family connection that Migara was made the Chief of the Army ( Senapathi ). However for reasons unknown, Migara was extremely cruel to his wife. Being unable to apprehend Migara, King Dhatusena vented his fury on Migara’s mother, his own sister, and ordered her to be burned alive.

From that point onwards, the story of Sigiriya unfolds like a Shakespearian tragedy. Migara’s heart and mind burned within him to take revenge on King Dhatusena. Avenging his mother’s cruel death became a maniacal obsession. And so he planned and plotted and found a ready, willing and able person whom he could inspire and instigate to fulfill this overriding obsession. This person was none other than King Dhatusena’s eldest son, Kasyapa. However Kasyapa though being the eldest son had no right to the throne since his mother was a Non- Royal concubine. Kasyapa knew it. He resented it.

Thus was planned between Migara the Chief of the Army and Kasyapa the King’s son a Royal coup. Fast Forward to 1962- A ‘Royal’ coup also involving a high ranking Army Officer. That was a failed coup. But that as they say is another story! Let’s move on. Migara who had won the fullest confidence of Kasyapa and knew very well how to exploit it arrested King Dhatusena and de-throned him. He then had Kasyapa enthroned as King. This was in 473 CE. The first step in this coup had been completed.

Now for the second. He convinced King Kasyapa that Dhatusena had large amounts of treasure, specially gold hidden in some secret place. Dhatusena was then confronted by the new king Kasyapa, who demanded to know where the hidden treasure was. Dhatusena took his captors to the borders of the Kalawewa which was one of the largest irrigation tanks he had built and taking some water from the tank in his hands, exclaimed that this was the only treasure he had. Infuriated and exasperated King Kasyapa ordered Migara to entomb his father alive into a wall.

According to an alternate story Dhatusena was buried alive on the bund of the Kalawewa. Whichever way the murder took place, Migara had avenged his mother’s murder. Meanwhile Moggallana, the rightful heir to the throne fled to India as he feared that he too would be killed. But the dastardly act of King Kasyapa incurred the ignominy of the people and the venerable monks. Patricide was something that could never have been condoned. It was against the teaching of Lord Buddha. King Kasyapa was a troubled man. The people were against him. The venerable monks were against him. His step-brother brother Mogallana was against him and was collecting an army of invasion. And to add to his misery he was constantly and contemptuously referred to as ” Pithru Ghatathaka Kasyapa.” ( Kasyapa –the paricide ) Abandoning Anuradhapura as his capital he moved to Sigiriya which was once a Buddhist monastery.. Here he built his fortress and his palace which has been called the eighth Wonder of the World. King Kasyapa felt well secured. He had left behind his fears and apprehensions. He now wanted to live in luxury. He lavished his wealth to make into reality his vision of creating a city similar to the mythological ‘Alakamanda’ –the ‘City of the Gods’ which was ruled by Kuvera, the god of plenty and prosperity.

Rising 200 meters from ground level the summit provides a 360 degree panoramic view of the adjacent jungles. Here was a unique harmony between nature and human imagination. It was also of strategic importance because any enemy army moving in, can be detected and defensive measures taken.

As any of today’s visitors enter through the Western gate what greets the eye are the royal gardens, interspersed with pools and fountains. These gardens were meant to be a type of pleasure park for the exclusive use of the royal family to relax. They extend for a few hundred meters from the base of the rock. And now begins the climb to the summit, which is not for the faint hearted as we shall see later. The massive brick stairways leads in a zig- zag to the Mirror Wall. Let us pause here for a while. According to one source the Mirror Wall was made from a special plaster comprising fine lime, egg white and honey. It was then buffed with bee’s wax to give a brilliant luster. In King Kasyapa’s time it was so well polished that the King could clearly see his refection as he walked by. Was it a sign of his vanity ? After all here was his palace which he believed to be similar to ‘The City of Gods’. And as the King was he not like Kuvera? If indeed it was his vanity he felt justified. Passing the Mirror Wall is a platform. No matter how intrepid you are it is better to pause awhile and take some deep breaths. More challenges lie ahead. There is a narrow metal staircase which leads to the frescoes. It is best to stop here and admire these semi-naked doe-eyed beautiful women. They are like heavenly nymphs (apsaras). There is much conjecture as to whom they depicted. Were they the King’s many wives, or members of the play-boy King’s Royal harem ? It is claimed that he had over 500 damsels selected for their sensuous beauty.

Having passed these damsels perhaps with some regret, one comes to the most difficult part of the climb. There is a narrow steel stairway on the exposed side of the rock. It is best not to look down below on the lush green scrubland. You may get a bout of acrophobia! And so we come to the summit and you can breathe a great sigh of relief not only for overcoming the challenge of climbing but also gazing at the magnificent landscape that stretches as far as eye can see.

This terraced summit is approximately 1.6 ha in extent. Here can be seen a number of water tanks, baths and the remains of the Royal Palace. There is also a stone slab like a seat which may have been the remains of a throne. There is also a 27 m x 21 m rock hewn water tank which was a water storage tank. The hydraulic systems, the landscaping, the terraces, all of these indicate unique creative skills and technologies. Sigiriya is said to be one of the finest examples of urban planning of the first millennium.

But we now need to get back to the Mirror Wall for there is a story to relate. On this Mirror Wall there can be seen graffiti in the form of poems written in Sinhala, Sanskrit and Tamil. According to historians and archeologists these graffiti were written long after Sigiriya was abandoned and converted once more into a Buddhist monastery. And then the question arises as to why these monks allowed visitors to enter and write poems on the Mirror Wall , many of which were love poems ? For example –

“Wet, cool dew drops Fragrant with perfume from flowers, Came the gentle breeze, jasmine and water lily Dance in the spring sunshine. Side- long glances of the golden hued ladies stab into my thoughts. Heaven itself cannot take my mind, As it has been captivated by one lass Among the five hundred I have seen.”

It must be noted that these graffiti is of great interest to scholars as it reveals the development of the Sinhala language and script.

But the saga of Sigiriya does not end. Once more the cold steel hand of intrigue and betrayal appears. And this time too it is Migara’s hand. And once more it is anger. And once more it is revenge. This time the victim is King Kasyapa. Annoyed that King Kasyapa did not permit him to conduct a large religious festival Migara secretly switched his loyalty from King Kasyapa to his half brother Moggallana who was in India waiting for an opportunity to return to Sri Lanka and regain the crown that was rightfully his.

Migara’s secret changing of loyalty was Moggallana’s cue to return. On hearing of this new but not unexpected threat King Kasyapa riding his Royal elephant and confident of his army, led by Migara, went into battle. This, despite his soothsayers warning him that it was not the auspicious time for war. At some point, his elephant sensing a swamp close at hand turned to get on to firmer ground. To Migara this was an opportunity sent by the gods. He ordered the army to retreat.

The army fled. King Kasyapa was now alone and abandoned . He knew that his end was near. Rather than being killed in battle he drew out his dagger placed it on his neck and slit his throat. It was in the year 495 CE. He had ruled for 18 years. Moggallana the victorious was not unmindful of his duties. He still respected his half brother and accorded him a Royal cremation. It is believed that the place was at Pidururangala. It is a few km away from Sigiriya and is also like Sigiriya formed by volcanic activity.

Features

Rebuilding Sri Lanka Through Inclusive Governance

In the immediate aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah, the government has moved swiftly to establish a Presidential Task Force for Rebuilding Sri Lanka with a core committee to assess requirements, set priorities, allocate resources and raise and disburse funds. Public reaction, however, has focused on the committee’s problematic composition. All eleven committee members are men, and all non-government seats are held by business personalities with no known expertise in complex national development projects, disaster management and addressing the needs of vulnerable populations. They belong to the top echelon of Sri Lanka’s private sector which has been making extraordinary profits. The government has been urged by civil society groups to reconsider the role and purpose of this task force and reconstitute it to be more representative of the country and its multiple needs.

The group of high-powered businessmen initially appointed might greatly help mobilise funds from corporates and international donors, but this group may be ill equipped to determine priorities and oversee disbursement and spending. It would be necessary to separate fundraising, fund oversight and spending prioritisation, given the different capabilities and considerations required for each. International experience in post disaster recovery shows that inclusive and representative structures are more likely to produce outcomes that are equitable, efficient and publicly accepted. Civil society, for instance, brings knowledge rooted in communities, experience in working with vulnerable groups and a capacity to question assumptions that may otherwise go unchallenged.

A positive and important development is that the government has been responsive to these criticisms and has invited at least one civil society representative to join the Rebuilding Sri Lanka committee. This decision deserves to be taken seriously and responded to positively by civil society which needs to call for more representation rather than a single representative. Such a demand would reflect an understanding that rebuilding after a national disaster cannot be undertaken by the state and the business community alone. The inclusion of civil society will strengthen transparency and public confidence, particularly at a moment when trust in institutions remains fragile. While one appointment does not in itself ensure inclusive governance, it opens the door to a more participatory approach that needs to be expanded and institutionalised.

Costly Exclusions

Going down the road of history, the absence of inclusion in government policymaking has cost the country dearly. The exclusion of others, not of one’s own community or political party, started at the very dawn of Independence in 1948. The Father of the Nation, D S Senanayake, led his government to exclude the Malaiyaha Tamil community by depriving them of their citizenship rights. Eight years later, in 1956, the Oxford educated S W R D Bandaranaike effectively excluded the Tamil speaking people from the government by making Sinhala the sole official language. These early decisions normalised exclusion as a tool of governance rather than accommodation and paved the way for seven decades of political conflict and three decades of internal war.

Exclusion has also taken place virulently on a political party basis. Both of Sri Lanka’s post Independence constitutions were decided on by the government alone. The opposition political parties voted against the new constitutions of 1972 and 1977 because they had been excluded from participating in their design. The proposals they had made were not accepted. The basic law of the country was never forged by consensus. This legacy continues to shape adversarial politics and institutional fragility. The exclusion of other communities and political parties from decision making has led to frequent reversals of government policy. Whether in education or economic regulation or foreign policy, what one government has done the successor government has undone.

Sri Lanka’s poor performance in securing the foreign investment necessary for rapid economic growth can be attributed to this factor in the main. Policy instability is not simply an economic problem but a political one rooted in narrow ownership of power. In 2022, when the people went on to the streets to protest against the government and caused it to fall, they demanded system change in which their primary focus was corruption, which had reached very high levels both literally and figuratively. The focus on corruption, as being done by the government at present, has two beneficial impacts for the government. The first is that it ensures that a minimum of resources will be wasted so that the maximum may be used for the people’s welfare.

Second Benefit

The second benefit is that by focusing on the crime of corruption, the government can disable many leaders in the opposition. The more opposition leaders who are behind bars on charges of corruption, the less competition the government faces. Yet these gains do not substitute for the deeper requirement of inclusive governance. The present government seems to have identified corruption as the problem it will emphasise. However, reducing or eliminating corruption by itself is not going to lead to rapid economic development. Corruption is not the sole reason for the absence of economic growth. The most important factor in rapid economic growth is to have government policies that are not reversed every time a new government comes to power.

For Sri Lanka to make the transition to self-sustaining and rapid economic development, it is necessary that the economic policies followed today are not reversed tomorrow. The best way to ensure continuity of policy is to be inclusive in governance. Instead of excluding those in the opposition, the mainstream opposition in particular needs to be included. In terms of system change, the government has scored high with regard to corruption. There is a general feeling that corruption in the country is much reduced compared to the past. However, with regard to inclusion the government needs to demonstrate more commitment. This was evident in the initial choice of cabinet ministers, who were nearly all men from the majority ethnic community. Important committees it formed, including the Presidential Task Force for a Clean Sri Lanka and the Rebuilding Sri Lanka Task Force, also failed at first to reflect the diversity of the country.

In a multi ethnic and multi religious society like Sri Lanka, inclusivity is not merely symbolic. It is essential for addressing diverse perspectives and fostering mutual understanding. It is important to have members of the Tamil, Muslim and other minority communities, and women who are 52 percent of the population, appointed to important decision making bodies, especially those tasked with national recovery. Without such representation, the risk is that the very communities most affected by the crisis will remain unheard, and old grievances will be reproduced in new forms. The invitation extended to civil society to participate in the Rebuilding Sri Lanka Task Force is an important beginning. Whether it becomes a turning point will depend on whether the government chooses to make inclusion a principle of governance rather than treat it as a show of concession made under pressure.

by Jehan Perera

Features

Reservoir operation and flooding

Former Director General of Irrigation, G.T. Dharmasena, in an article, titled “Revival of Innovative systems for reservoir operation and flood forecasting” in The Island of 17 December, 2025, starts out by stating:

“Most reservoirs in Sri Lanka are agriculture and hydropower dominated. Reservoir operators are often unwilling to acknowledge the flood detention capability of major reservoirs during the onset of monsoons. Deviating from the traditional priority for food production and hydropower development, it is time to reorient the operational approach of major reservoirs operators under extreme events, where flood control becomes a vital function. While admitting that total elimination of flood impacts is not technically feasible, the impacts can be reduced by efficient operation of reservoirs and effective early warning systems”.

Addressing the question often raised by the public as to “Why is flooding more prominent downstream of reservoirs compared to the period before they were built,” Mr. Dharmasena cites the following instances: “For instance, why do (sic) Magama in Tissamaharama face floods threats after the construction of the massive Kirindi Oya reservoir? Similarly, why does Ambalantota flood after the construction of Udawalawe Reservoir? Furthermore, why is Molkawa, in the Kalutara District area, getting flooded so often after the construction of Kukule reservoir”?

“These situations exist in several other river basins, too. Engineers must, therefore, be mindful of the need to strictly control the operation of the reservoir gates by their field staff. (Since) “The actual field situation can sometimes deviate significantly from the theoretical technology… it is necessary to examine whether gate operators are strictly adhering to the operational guidelines, as gate operation currently relies too much on the discretion of the operator at the site”.

COMMENT

For Mr. Dharmasena to bring to the attention of the public that “gate operation currently relies too much on the discretion of the operator at the site”, is being disingenuous, after accepting flooding as a way of life for ALL major reservoirs for decades and not doing much about it. As far as the public is concerned, their expectation is that the Institution responsible for Reservoir Management should, not only develop the necessary guidelines to address flooding but also ensure that they are strictly administered by those responsible, without leaving it to the arbitrary discretion of field staff. This exercise should be reviewed annually after each monsoon, if lives are to be saved and livelihoods are to be sustained.

IMPACT of GATE OPERATION on FLOODING

According to Mr. Dhamasena, “Major reservoir spillways are designed for very high return periods… If the spillway gates are opened fully when reservoir is at full capacity, this can produce an artificial flood of a very large magnitude… Therefore, reservoir operators must be mindful in this regard to avoid any artificial flood creation” (Ibid). Continuing, he states: “In reality reservoir spillways are often designed for the sole safety of the reservoir structure, often compromising the safety of the downstream population. This design concept was promoted by foreign agencies in recent times to safeguard their investment for dams. Consequently, the discharge capacities of these spill gates significantly exceed the natural carrying capacity of river(s) downstream” (Ibid).

COMMENT

The design concept where priority is given to the “sole safety of the structure” that causes the discharge capacity of spill gates to “significantly exceed” the carrying capacity of the river is not limited to foreign agencies. Such concepts are also adopted by local designers as well, judging from the fact that flooding is accepted as an inevitable feature of reservoirs. Since design concepts in their current form lack concern for serious destructive consequences downstream and, therefore, unacceptable, it is imperative that the Government mandates that current design criteria are revisited as a critical part of the restoration programme.

CONNECTIVITY BETWEEN GATE OPENINGS and SAFETY MEASURES

It is only after the devastation of historic proportions left behind by Cyclone Ditwah that the Public is aware that major reservoirs are designed with spill gate openings to protect the safety of the structure without factoring in the consequences downstream, such as the safety of the population is an unacceptable proposition. The Institution or Institutions associated with the design have a responsibility not only to inform but also work together with Institutions such as Disaster Management and any others responsible for the consequences downstream, so that they could prepare for what is to follow.

Without working in isolation and without limiting it only to, informing related Institutions, the need is for Institutions that design reservoirs to work as a team with Forecasting and Disaster Management and develop operational frameworks that should be institutionalised and approved by the Cabinet of Ministers. The need is to recognize that without connectivity between spill gate openings and safety measures downstream, catastrophes downstream are bound to recur.

Therefore, the mandate for dam designers and those responsible for disaster management and forecasting should be for them to jointly establish guidelines relating to what safety measures are to be adopted for varying degrees of spill gate openings. For instance, the carrying capacity of the river should relate with a specific openinig of the spill gate. Another specific opening is required when the population should be compelled to move to high ground. The process should continue until the spill gate opening is such that it warrants the population to be evacuated. This relationship could also be established by relating the spill gate openings to the width of the river downstream.

The measures recommended above should be backed up by the judicious use of the land within the flood plain of reservoirs for “DRY DAMS” with sufficient capacity to intercept part of the spill gate discharge from which excess water could be released within the carrying capacity of the river. By relating the capacity of the DRY DAM to the spill gate opening, a degree of safety could be established. However, since the practice of demarcating flood plains is not taken seriously by the Institution concerned, the Government should introduce a Bill that such demarcations are made mandatory as part of State Land in the design and operation of reservoirs. Adopting such a practice would not only contribute significantly to control flooding, but also save lives by not permitting settlement but permitting agricultural activities only within these zones. Furthermore, the creation of an intermediate zone to contain excess flood waters would not tax the safety measures to the extent it would in the absence of such a safety net.

CONCLUSION

Perhaps, the towns of Kotmale and Gampola suffered severe flooding and loss of life because the opening of spill gates to release the unprecedented volumes of water from Cyclone Ditwah, was warranted by the need to ensure the safety of Kotmale and Upper Kotmale Dams.

This and other similar disasters bring into focus the connectivity that exists between forecasting, operation of spill gates, flooding and disaster management. Therefore, it is imperative that the government introduce the much-needed legislative and executive measures to ensure that the agencies associated with these disciplines develop a common operational framework to mitigate flooding and its destructive consequences. A critical feature of such a framework should be the demarcation of the flood plain, and decree that land within the flood plain is a zone set aside for DRY DAMS, planted with trees and free of human settlements, other than for agricultural purposes. In addition, the mandate of such a framework should establish for each river basin the relationship between the degree to which spill gates are opened with levels of flooding and appropriate safety measures.

The government should insist that associated Agencies identify and conduct a pilot project to ascertain the efficacy of the recommendations cited above and if need be, modify it accordingly, so that downstream physical features that are unique to each river basin are taken into account and made an integral feature of reservoir design. Even if such restrictions downstream limit the capacities to store spill gate discharges, it has to be appreciated that providing such facilities within the flood plain to any degree would mitigate the destructive consequences of the flooding.

By Neville Ladduwahetty

Features

Listening to the Language of Shells

The ocean rarely raises its voice. Instead, it leaves behind signs — subtle, intricate and enduring — for those willing to observe closely. Along Sri Lanka’s shores, these signs often appear in the form of seashells: spiralled, ridged, polished by waves, carrying within them the quiet history of marine life. For Marine Naturalist Dr. Malik Fernando, these shells are not souvenirs of the sea but storytellers, bearing witness to ecological change, resilience and loss.

“Seashells are among the most eloquent narrators of the ocean’s condition,” Dr. Fernando told The Island. “They are biological archives. If you know how to read them, they reveal the story of our seas, past and present.”

A long-standing marine conservationist and a member of the Marine Subcommittee of the Wildlife & Nature Protection Society (WNPS), Dr. Fernando has dedicated much of his life to understanding and protecting Sri Lanka’s marine ecosystems. While charismatic megafauna often dominate conservation discourse, he has consistently drawn attention to less celebrated but equally vital marine organisms — particularly molluscs, whose shells are integral to coastal and reef ecosystems.

“Shells are often admired for their beauty, but rarely for their function,” he said. “They are homes, shields and structural components of marine habitats. When shell-bearing organisms decline, it destabilises entire food webs.”

Sri Lanka’s geographical identity as an island nation, Dr. Fernando says, is paradoxically underrepresented in national conservation priorities. “We speak passionately about forests and wildlife on land, but our relationship with the ocean remains largely extractive,” he noted. “We fish, mine sand, build along the coast and pollute, yet fail to pause and ask how much the sea can endure.”

Through his work with the WNPS Marine Subcommittee, Dr. Fernando has been at the forefront of advocating for science-led marine policy and integrated coastal management. He stressed that fragmented governance and weak enforcement continue to undermine marine protection efforts. “The ocean does not recognise administrative boundaries,” he said. “But unfortunately, our policies often do.”

He believes that one of the greatest challenges facing marine conservation in Sri Lanka is invisibility. “What happens underwater is out of sight, and therefore out of mind,” he said. “Coral bleaching, mollusc depletion, habitat destruction — these crises unfold silently. By the time the impacts reach the shore, it is often too late.”

Seashells, in this context, become messengers. Changes in shell thickness, size and abundance, Dr. Fernando explained, can signal shifts in ocean chemistry, rising temperatures and increasing acidity — all linked to climate change. “Ocean acidification weakens shells,” he said. “It is a chemical reality with biological consequences. When shells grow thinner, organisms become more vulnerable, and ecosystems less stable.”

Seashells, in this context, become messengers. Changes in shell thickness, size and abundance, Dr. Fernando explained, can signal shifts in ocean chemistry, rising temperatures and increasing acidity — all linked to climate change. “Ocean acidification weakens shells,” he said. “It is a chemical reality with biological consequences. When shells grow thinner, organisms become more vulnerable, and ecosystems less stable.”

Climate change, he warned, is no longer a distant threat but an active force reshaping Sri Lanka’s marine environment. “We are already witnessing altered breeding cycles, migration patterns and species distribution,” he said. “Marine life is responding rapidly. The question is whether humans will respond wisely.”

Despite the gravity of these challenges, Dr. Fernando remains an advocate of hope rooted in knowledge. He believes public awareness and education are essential to reversing marine degradation. “You cannot expect people to protect what they do not understand,” he said. “Marine literacy must begin early — in schools, communities and through public storytelling.”

It is this belief that has driven his involvement in initiatives that use visual narratives to communicate marine science to broader audiences. According to Dr. Fernando, imagery, art and heritage-based storytelling can evoke emotional connections that data alone cannot. “A well-composed image of a shell can inspire curiosity,” he said. “Curiosity leads to respect, and respect to protection.”

Shells, he added, also hold cultural and historical significance in Sri Lanka, having been used for ornamentation, ritual objects and trade for centuries. “They connect nature and culture,” he said. “By celebrating shells, we are also honouring coastal communities whose lives have long been intertwined with the sea.”

However, Dr. Fernando cautioned against romanticising the ocean without acknowledging responsibility. “Celebration must go hand in hand with conservation,” he said. “Otherwise, we risk turning heritage into exploitation.”

He was particularly critical of unregulated shell collection and commercialisation. “What seems harmless — picking up shells — can have cumulative impacts,” he said. “When multiplied across thousands of visitors, it becomes extraction.”

As Sri Lanka continues to promote coastal tourism, Dr. Fernando emphasised the need for sustainability frameworks that prioritise ecosystem health. “Tourism must not come at the cost of the very environments it depends on,” he said. “Marine conservation is not anti-development; it is pro-future.”

Dr. Malik Fernando

Reflecting on his decades-long engagement with the sea, Dr. Fernando described marine conservation as both a scientific pursuit and a moral obligation. “The ocean has given us food, livelihoods, climate regulation and beauty,” he said. “Protecting it is not an act of charity; it is an act of responsibility.”

He called for stronger collaboration between scientists, policymakers, civil society and the private sector. “No single entity can safeguard the ocean alone,” he said. “Conservation requires collective stewardship.”

Yet, amid concern, Dr. Fernando expressed cautious optimism. “Sri Lanka still has immense marine wealth,” he said. “Our reefs, seagrass beds and coastal waters are resilient, if given a chance.”

Standing at the edge of the sea, shells scattered along the sand, one is reminded that the ocean does not shout its warnings. It leaves behind clues — delicate, enduring, easily overlooked. For Dr. Malik Fernando, those clues demand attention.

“The sea is constantly communicating,” he said. “In shells, in currents, in changing patterns of life. The real question is whether we, as a society, are finally prepared to listen — and to act before silence replaces the story.”

By Ifham Nizam

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports6 days ago

Sports6 days agoChief selector’s remarks disappointing says Mickey Arthur

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoDisasters do not destroy nations; the refusal to change does

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoSri Lanka’s coastline faces unfolding catastrophe: Expert

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

Midweek Review7 days ago

Midweek Review7 days agoYear ends with the NPP govt. on the back foot

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne