Opinion

The Role of Domestic Aviation in Sri Lankan Tourism

This is a report by the Organization of Professional Associations. Resource personnel on Panel were Capt. Amal Wahid, General Manager, Air Senok/Senok Aviation (Pvt) Ltd., Capt. Lasantha Dahanayake, Director Flight Operations, Saffron Aviation (Pvt) Ltd, parent company of Cinnamon Air Asitha Ranaweera, Accountable Manager and Deputy Chief Executive FITS (Pvt) Ltd (Friends In The Sky), Kasun Abeynayaka, Senior Lecturer/Assistant Director Industry Engagement, Events, Travel and Tourism, William Angliss Institute@SLIIT. Moderator was Capt. G.A. Fernando, Member, Executive Council of Organisation of Professional Associations (OPA) & Member, Association of Airline Pilots

Resource personnel on Panel:

1. Capt. Amal Wahid, General Manager, Air Senok/Senok Aviation (Pvt) Ltd

2. Capt. Lasantha Dahanayake, Director Flight Operations, Saffron Aviation (Pvt) Ltd, parent company of Cinnamon Air

3. Asitha Ranaweera, Accountable Manager and Deputy Chief Executive FITS (Pvt) Ltd (Friends In The Sky)

4. Kasun Abeynayaka, Senior Lecturer/Assistant Director Industry Engagement, Events, Travel and Tourism, William Angliss Institute @ SLIIT

Moderator:

Capt. G.A. Fernando, Member, Executive Council of Organisation of Professional Associations (OPA) & Member, Association of Airline Pilots

(Continued from yesterday (09)

From a Sri Lankan tourism point of view, the years between 2010 and 2020 could be called the ‘Golden Era’. In the year 2018 there were 2.3 million foreign tourists visiting Sri Lanka. In fact, Sri Lankan Tourism was the 3rd largest contributor to the national economy. Our Tourism Industry is now competing with Singapore and Maldives.

Sri Lanka now has five international airports. However, less than 10% of them have been utilised by tourists using domestic air transportation. In contrast, Maldives started seaplane operations in 1990 and is now flourishing with participation of three operators, with access to all tourist resorts.

‘Luxury tourism’ has to be looked at in terms of the five C’s: Cuisine, Culture, Community, Content and Customisation. Domestic aviation will fall into the category defining Content, which is currently lacking. Furthermore a five-year concept (the five A’s) is being considered for tourism in Sri Lanka, namely: Accessibility, Amenities, Attractively, Accommodation and Authenticity. Domestic airlines should facilitate Accessibility. The industrial leader in domestic aviation is Cinnamon Air, catering to a niche market rather than the mass market.

Last month there were 33,000 tourists and up to 20th June there were 61,000, led mainly by travellers from India. This was very encouraging.

The Challenges

In 2010 an International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) audit was imminent. Without much thought given to the applicability to domestic aviation, the Aviation Act Number 14 of 2010 was hastily introduced. This resulted in over-regulation of simple operations that increased the fixed costs due to employment of number of additional post-holders, not unlike practice in a complex operation. That situation exists because there are no professionally qualified personnel to handle domestic aviation at CAASL.

The domestic aircraft are kept grounded for long periods because of no Aircraft on Ground (AOG) process to import spare parts as soon as possible. Domestic security procedures are not streamlined and coordinated with the National Intelligence Bureau (NIB), Airport and Aviation Services Sri Lanka (AASL), and Sri Lanka Air Force (SLAF). After the Easter Sunday terrorist attacks of 2019, additional security measures such as physical ‘frisking’ have been introduced, to the displeasure and annoyance of tourists.

Cessna 208 Caravan amphibian seaplane of Cinnamon Air, 4R-CAF

In addition all, domestic flight movements are restricted by the SLAF. Approvals are required from far too many organisations. It was suggested that there should only be a maximum of two organisations facilitating the operations, with all approvals addressed via a single regulatory body.

Additionally, today there is no dedicated domestic terminal for operators at Colombo-BIA, a situation that creates confusion for passengers. The cost of establishing Cinnamon Air’s own terminal at BIA will undoubtedly be passed on to the company’s passengers, driving ticket prices higher.

Navigation aids at Ratmalana International Airport (RIA) are not sufficient. After the crash in 2015 of a SLAF Antonov An-32 transport due to bad visibility at Hokandara which is on the final approach to RIA, the SLAF requested CAASL to provide a usable navigational radio aid, but to no avail yet.

In the Sri Lanka Civil Aviation Policy 2017 there is a clause which authorises the use of ‘Cabotage’ rights. Wikipedia defines cabotage rights as “the right of a company from one country to trade in another country. In aviation, it is the right to operate within the domestic borders of another country.”

Most countries do not permit aviation cabotage, and there are strict sanctions against it, for reasons of economic protectionism, national security, or public safety. It was therefore declared that cabotage rights should be handled with grave concern, and should be discussed further at a higher levels.

There was a recent development in FitsAir (Friends in the Sky) when the company lost 50% of its employee cadre (pilots, engineers, mechanics, flight dispatchers and cabin crew), as many migrated to greener pastures. In the near future, to prevent operations coming to an almost standstill FitsAir may have to hire expatriates to replace the lost knowledge and experience which cannot be rebuilt overnight.

With reference to spares, FitsAir ran an ATR 72 operation in Indonesia. In contrast to Sri Lankan operations, they had only a minimum stock of spares on the rack. The other spares were ordered as and when required, with Indonesian Customs clearing and delivering them in a timely manner, usually within 24 hours. That was the guarantee in place. In a comparative Sri Lankan scenario, it would have taken many months to obtain the same spare parts, resulting in the aircraft remaining grounded in the interim while losing money for its owner/operator.

At present, a tourist wishing to transfer from an international flight to a domestic flight or vice versa at BIA, is not facilitated with a seamless, coordinated process by Customs, Immigration, Quarantine (CIQ), and the Airport and Aviation Security (AASL) Security. Instead, he/she must walk a long way in the process that is unacceptable, especially to ‘high end’ tourists. There is no satisfactory place in the BIA terminal for a tourist to wait. In short there seems to be a major communication problem, for which tourists should not be penalised. Domestic aviation is an expensive yet important exercise in the interest of an attractive and hassle-free tourist experience. Yet domestic airline brand-names and the availability of those airlines’ services within Sri Lanka are not mentioned in websites on Sri Lankan tourism, although other stake-holders are acknowledged.

It was felt that tourism marketing was carried out haphazardly, and selling was unplanned. For example, Singapore has 49,000 MICE (Meetings, Incentives, Conference and Exhibition) tourism venues, while Sri Lanka sadly has fewer than ten. Sri Lanka needs to actively capture that market, but so far has done nothing of the sort. Every organisation is living in its own bubble and not working as a team.

The wedding market, catering especially to visitors from the Indian subcontinent, is another potentially high foreign exchange earner in which domestic aviation can actively participate.

Overall, there is a lack of awareness by all concerned, including the regulator, who should come at least halfway out of his corner.

What can be done about it?

ATR 72-200 of FitsAir, 4R-EXN

There was also a suggestion that domestic aviation should come under the umbrella of the Tourism Development Authority. At the moment the rapport maintained with the Tourism Authority is not encouraging.

It was suggested that, as in India, a Viability Fund and Connectivity Fund (to safeguard operator and customer alike) should be established. It was declared as doable and a good way of jump-starting the domestic aviation industry.

Possible Solutions as contained in the Executive Summary

· Third level airlines could be established to train and develop personnel for the international, regional and domestic aviation industries.

· Air travel facilities available should be publicised abroad through our embassies/high commissions.

· Domestic aviation must be subsidised by the government, perhaps using the Tourism Development Fund. This Tourism Development Levy (TDL) should include a component for aviation or domestic aviation strategies, which is a lengthy process which takes time to begin functioning.

· 16 domestic airports available.

· CAASL must liberalise and not use international standards (SARP’s) rigidly on domestic services (alternative means of compliance could achieve equal or better safety standards).

· The Government must not encourage subsidised airlines to distort the fair prices of domestic air travel. For instance the SLAF-operated Helitours model.

· Encourage private investment.

· Realistic CAASL security oversight (to facilitate and not to obstruct).

· Always ‘Safety First’.

· Available national industrial experts to be utilised.

· Healthy competition to be established in a level playing field.

· Domestic air service orientated and fully integrated with road and rail as suggested by the Aviation Policy of 2017.

Note:

A Viability Fund to safeguard the operator assuming that the flight was operating full every time all the time. For example, if an eight-seat aircraft was flying with only four passengers, then the other four seats would be subsidised by the fund.

A Connectivity Fund to cap the ticket fare to a more affordable value to popularise the flight.

Both funds to operate for a limited time, e.g. three or five years.

Finally, it was suggested that to move forward, domestic aviation should work closely with SLAITO (Sri Lanka Association for Inbound Tourist Operators) which has a seat in almost all the Tourist Development Forums.

Opinion

We do not want to be press-ganged

Reference ,the Indian High Commissioner’s recent comments ( The Island, 9th Jan. ) on strong India-Sri Lanka relationship and the assistance granted on recovering from the financial collapse of Sri Lanka and yet again for cyclone recovery., Sri Lankans should express their thanks to India for standing up as a friendly neighbour.

On the Defence Cooperation agreement, the Indian High Commissioner’s assertion was that there was nothing beyond that which had been included in the text. But, dear High Commissioner, we Sri Lankans have burnt our fingers when we signed agreements with the European nations who invaded our country; they took our leaders around the Mulberry bush and made our nation pay a very high price by controlling our destiny for hundreds of years. When the Opposition parties in the Parliament requested the Sri Lankan government to reveal the contents of the Defence agreements signed with India as per the prevalent common practice, the government’s strange response was that India did not want them disclosed.

Even the terms of the one-sided infamous Indo-Sri Lanka agreement, signed in 1987, were disclosed to the public.

Mr. High Commissioner, we are not satisfied with your reply as we are weak, economically, and unable to clearly understand your “India’s Neighbourhood First and Mahasagar policies” . We need the details of the defence agreements signed with our government, early.

RANJITH SOYSA

Opinion

When will we learn?

At every election—general or presidential—we do not truly vote, we simply outvote. We push out the incumbent and bring in another, whether recycled from the past or presented as “fresh.” The last time, we chose a newcomer who had spent years criticising others, conveniently ignoring the centuries of damage they inflicted during successive governments. Only now do we realise that governing is far more difficult than criticising.

There is a saying: “Even with elephants, you cannot bring back the wisdom that has passed.” But are we learning? Among our legislators, there have been individuals accused of murder, fraud, and countless illegal acts. True, the courts did not punish them—but are we so blind as to remain naive in the face of such allegations? These fraudsters and criminals, and any sane citizen living in this decade, cannot deny those realities.

Meanwhile, many of our compatriots abroad, living comfortably with their families, ignore these past crimes with blind devotion and campaign for different parties. For most of us, the wish during an election is not the welfare of the country, but simply to send our personal favourite to the council. The clearest example was the election of a teledrama actress—someone who did not even understand the Constitution—over experienced and honest politicians.

It is time to stop this bogus hero worship. Vote not for personalities, but for the country. Vote for integrity, for competence, and for the future we deserve.

Deshapriya Rajapaksha

Opinion

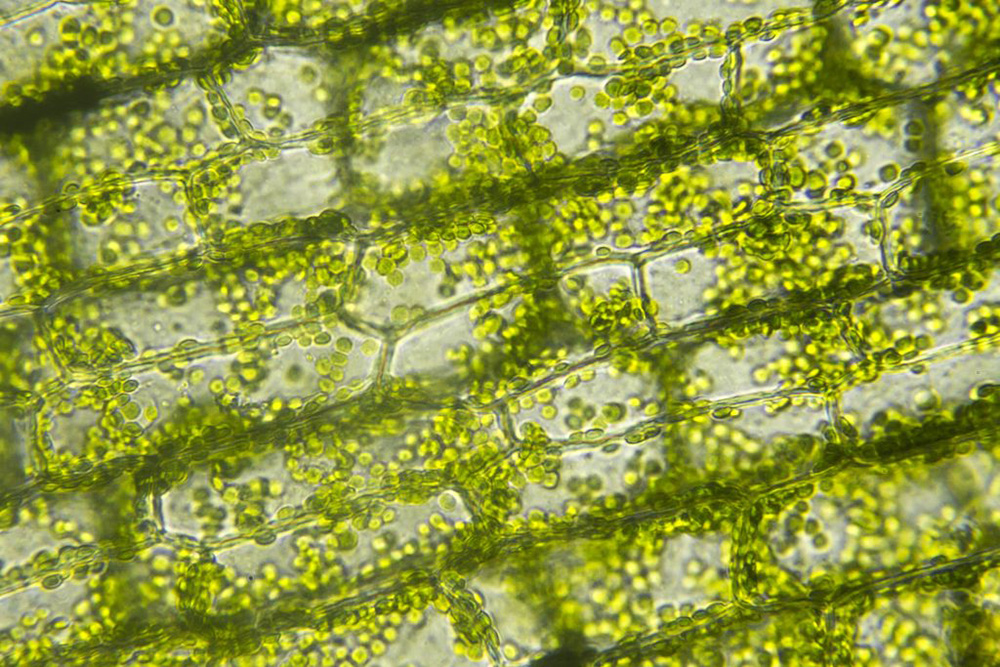

Chlorophyll –The Life-giver is in peril

Chlorophyll is the green pigment found in plants, algae, and cyanobacteria. It is essential for photosynthesis, the process by which light energy is converted into chemical energy to sustain life on Earth. As it is green it reflects Green of the sunlight spectrum and absorbs its Red and Blue ranges. The energy in these rays are used to produce carbohydrates utilising water and carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen in the process. Thus, it performs, in this reaction, three functions essential for life on earth; it produces food and oxygen and removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to maintain equilibrium in our environment. It is one of the wonders of nature that are in peril today. It is essential for life on earth, at least for the present, as there are no suitable alternatives. While chlorophyll can be produced in a lab, it cannot be produced using simple, everyday chemicals in a straightforward process. The total synthesis of chlorophyll is an extremely complex multi-step organic chemistry process that requires specialized knowledge, advanced laboratory equipment, and numerous complex intermediary compounds and catalysts.

Chlorophyll probably evolved inside bacteria in water and migrated to land with plants that preceded animals who also evolved in water. Plants had to come on land first to oxygenate the atmosphere and make it possible for animals to follow. There was very little oxygen in the ocean or on the surface before chlorophyll carrying bacteria and algae started photosynthesis. Now 70% of our atmospheric oxygen is produced by sea phytoplankton and algae, hence the importance of the sea as a source of oxygen.

Chemically, chlorophyll is a porphyrin compound with a central magnesium (Mg²⁺) ion. Factors that affect its production and function are light intensity, availability of nutrients, especially nitrogen and magnesium, water supply and temperature. Availability of nutrients and temperature could be adversely affected due to sea pollution and global warming respectively.

Temperature range for optimum chlorophyll function is 25 – 35 C depending on the types of plants. Plants in temperate climates are adopted to function at lower temperatures and those in tropical regions prefer higher temperatures. Chlorophyll in most plants work most efficiently at 30 C. At lower temperatures it could slow down and become dormant. At temperatures above 40 C chlorophyll enzymes begin to denature and protein complexes can be damaged. Photosynthesis would decline sharply at these high temperatures.

Global warming therefore could affect chlorophyll function and threaten its very existence. Already there is a qualitative as well as quantitative decline of chlorophyll particularly in the sea. The last decade has been the hottest ten years and 2024 the hottest year since recording had started. The ocean absorbs 90% of the excess heat that reaches the Earth due to the greenhouse effect. Global warming has caused sea surface temperatures to rise significantly, leading to record-breaking temperatures in recent years (like 2023-2024), a faster warming rate (four times faster than 40 years ago), and more frequent, intense marine heatwaves, disrupting marine life and weather patterns. The ocean’s surface is heating up much faster, about four times quicker than in the late 1980s, with the last decade being the warmest on record. 2023 and 2024 saw unprecedented high sea surface temperatures, with some periods exceeding previous records by large margins, potentially becoming the new normal.

Half of the global sea surface has gradually changed in colour indicating chlorophyll decline (Frankie Adkins, 2024, Z Hong, 2025). Sea is blue in colour due to the absorption of Red of the sunlight spectrum by water and reflecting Blue. When the green chlorophyll of the phytoplankton is decreased the sea becomes bluer. Researchers from MIT and Georgia Tech found these color changes are global, affecting over half the ocean’s surface in the last two decades, and are consistent with climate model predictions. Sea phytoplankton and algae produce more than 70% of the atmospheric oxygen, replenishing what is consumed by animals. Danger to the life of these animals including humans due to decline of sea chlorophyll is obvious. Unless this trend is reversed there would be irreparable damage and irreversible changes in the ecosystems that involve chlorophyll function as a vital component.

The balance 30% of oxygen is supplied mainly by terrestrial plants which are lost due mainly to human action, either by felling and clearing or due to global warming. Since 2000, approximately 100 million hectares of forest area was lost globally by 2018 due to permanent deforestation. More recent estimates from the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) indicate that an estimated 420 million hectares of forest have been lost through deforestation since 1990, with a net loss of approximately 4.7 million hectares per year between 2010 and 2020 (accounting for forest gains by reforestation). From 2001 to 2024, there had been a total of 520 million hectares of tree cover loss globally. This figure includes both temporary loss (e.g., due to fires or logging where forests regrow) and permanent deforestation. Roughly 37% of tree cover loss since 2000 was likely permanent deforestation, resulting in conversion to non-forest land uses such as agriculture, mining, or urban development. Tropical forests account for the vast majority (nearly 94%) of permanent deforestation, largely driven by agricultural expansion. Limiting warming to 1.5°C significantly reduces risks, but without strong action, widespread plant loss and biodiversity decline are projected, making climate change a dominant threat to nature, notes the World Economic Forum. Tropical trees are Earth’s climate regulators—they cool the planet, store massive amounts of carbon, control rainfall, and stabilize global climate systems. Losing them would make climate change faster, hotter, and harder to reverse.

Another vital function of chlorophyll is carbon fixing. Carbon fixation by plants is crucial because it converts atmospheric carbon dioxide into organic compounds, forming the base of the food web, providing energy/building blocks for life, regulating Earth’s climate by removing greenhouse gases, and driving the global carbon cycle, making life as we know it possible. Plants use carbon fixation (photosynthesis) to create their own food (sugars), providing energy and organic matter that sustains all other life forms. By absorbing vast amounts of CO2 (a greenhouse gas) from the atmosphere, plants help control its concentration, mitigating global warming. Chlorophyll drives the Carbon Cycle, it’s the primary natural mechanism for moving inorganic carbon into the biosphere, making it available for all living organisms.

In essence, carbon fixation turns the air we breathe out (carbon dioxide) into the food we eat and the air we breathe in (oxygen), sustaining ecosystems and regulating our planet’s climate.

While land plants store much more total carbon in their biomass, marine plants (like phytoplankton) and algae fix nearly the same amount of carbon annually as all terrestrial plants combined, making the ocean a massive and highly efficient carbon sink, especially coastal ecosystems that sequester carbon far faster than forests. Coastal marine plants (mangroves, salt marshes, seagrasses) are extremely efficient carbon sequesters, absorbing carbon at rates up to 50 times faster than terrestrial forests.

If Chlorophyll decline, which is mainly due to human action driven by uncontrolled greed, is not arrested as soon as possible life on Earth would not be possible.

(Some information was obtained from Wikipedia)

by N. A. de S. Amaratunga ✍️

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

News3 days ago

News3 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II