Features

The Rohingya question and states’ international obligations

The presence of Rohingya refugees in Sri Lanka has prompted sections in the South of the country to raise some concerns in connection with it but The Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka’s (THRCSL) recent report on the issue, if received and read in a spirit of reconciliation and humanity, should put their minds at ease.

The presence of Rohingya refugees in Sri Lanka has prompted sections in the South of the country to raise some concerns in connection with it but The Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka’s (THRCSL) recent report on the issue, if received and read in a spirit of reconciliation and humanity, should put their minds at ease.

To be sure, there is considerable substance in the objections and worries of the relevant Southern quarters but the majority of the refugees in question need to be seen as victims of complex political circumstances in their countries of origin over which they do not have any control.

Those Rohingyas who are now literally adrift in the seas of South Asia and beyond, are strictly speaking stateless. Most of them are escaping endemic political turmoil and runaway lawlessness in the Rakhine state of Mynamar and the spillover of such tensions into the Myanmar-Bangladesh border and beyond.

There has been playing out in the Rakhine region over the decades a Rohingya armed struggle for autonomy but the majority of the Rohingyas are not in any way supportive of this armed struggle which is an expression of the Rohingyas’ awareness of their separate identity as a community, although they possess a wider Muslim identity as well.

But there has been an influx of Rohingya refugees to several neighbouring countries from this conflict, including very significantly Bangladesh, and this has been triggering concerns among the wider publics in those states which are compelled to manage the Rohingya refugee presence amid economic pressures of their own.

The problems arising from the Rohingya refugee presence have been compounded by the rise of Islamic militancy in South Asia and the tendency among some of these militant groups to exploit this presence for the propagation of their causes.

However, this does not take away from the fact that the majority of Rohingyas are helpless victims of circumstance. They are caught up in the metaphorical ‘exchange of fire’ between mutually suspicious states that are compelled to contend with issues growing out of the rise of Islamic militancy. But for the majority of Rohingyas such endemic conflicts among states translate into displacement, statelessness and growing powerlessness.

For an enlightened understanding of what states need to do in connection with the refugee crisis and connected questions it would be necessary to read the THRCSL report above mentioned. States that are members of the UN family are obliged to ratify and implement a number of conventions related to refugees and the THRCSL mentions some of these. They are: The 1951 Convention on Refugees; 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons; 1961 Convention on the Reduction of the Stateless and the Rights of Refugees and Stateless Persons within Sri Lanka.

If Sri Lanka and other countries facing a refugee influx have not adopted these laws they would need to do so without further delay if they are opting to remain within the UN fold. In this connection, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights should be seen to be of fundamental importance. The Declaration is the fountainhead, so to speak, of international humanitarian law and UN members states have no choice but to adhere to it.

Contentious issues are likely to grow out of the implementation part of the mentioned conventions but it is best that signatory states take up these matters with the relevant key agencies of the UN rather than grouch over matters that surface from their inalienable obligations towards the stateless and homeless.

It was encouraging to note a Southern group in Sri Lanka mentioning that the Lankan government should draw the attention of the UNHRC to the fact that the state is not a signatory to some of the mentioned refugee conventions. This is the way to go. A dialogue process with the UNHRC, which does not happen to be very popular in Sri Lanka, on such issues would perhaps throw up fresh insights on Sri Lanka’s obligations on refugee issues that may then convince the state to sign and ratify the conventions concerned.

There needs to be a flourishing of such positive approaches to meeting Sri Lanka’s obligations as a UN member state. The present most unhappy existence of being a UN member state and not implementing attendant obligations needs to end if Sri Lanka is not to be accused of ‘double speak’ and ‘double think’.

Meanwhile, identity politics and connected problems are bound to remain in South Asia and bedevil all efforts by states of the region to see eye-to-eye on issues such as the stateless. The yawning ‘democratic deficit’ in South Asia continues to be a formidable challenge.

But all efforts should be made to reduce this deficit through collaborative efforts among the concerned states. This is so because increasing democratization of states remains the most effective means of making identity politics irrelevant and the latter is a primary cause for the break-up of states, which process throws-up troubling consequences, such as statelessness and refugees.

Fresh initiatives need to be undertaken by the ‘South Asian Eight’ to end the continuing ‘Cold War’-type situation between India and Pakistan, since they hold the key to re-activating SAARC and making it workable once again. It ought to be plain to see that it is only the SAARC spirit that could help in ushering a degree of solidarity in South Asia which could go some distance in resolving issues growing out of nation-breaking.

Once again, South-South cooperation should be seen as a compelling necessity. If vital sections of the South come to this realization and recognize the need for such intra-regional cooperation, the coming back to power of Donald Trump could be considered as having yielded some good, though in a highly negative way. Because Trump has made it all too plain that he would not be considering it obligatory on the part of the US to help ease the lot of the South any more.

The South would have no choice but to fall back on strategies of self-reliance. No doubt, this situation would accrue to the benefit of the world’s powerless. Self-reliance is the best option and the only key to unravelling external shackles that bind the South to the North.

Meanwhile, those sections of Southern Sri Lanka that are tending to cheer Trump on need to put the brakes on any such idle distractions. The message that Trump has for the world is one of division and strife. By rolling back almost all the progressive ventures that have come out of Washington over the years, Trump is plunging the world into further ‘disorder’. The international community needs to brace for stepped-up nation-breaking.

Features

Sri Lanka Through Loving Eyes:A Call to Fix What Truly Matters

Love of country, pride, and the responsibility to be honest

I am a Sri Lankan who has lived in Australia for the past 38 years. Australia has been very good to my family and me, yet Sri Lanka has never stopped being home. That connection endures, which is why we return every second year—sometimes even annually—not out of nostalgia, but out of love and pride in our country.

My recent visit reaffirmed much of what makes Sri Lanka exceptional: its people, culture, landscapes, and hospitality remain truly world-class. Yet loving one’s country also demands honesty, particularly when shortcomings risk undermining our future as a serious global tourism destination.

When Sacred and Iconic Sites Fall Short

One of the most confronting experiences occurred during our visit to Sri Pada (Adam’s Peak). This sacred site, revered across multiple faiths, attracts pilgrims and tourists from around the world. Sadly, the severe lack of basic amenities—especially clean, accessible toilets—was deeply disappointing. At moments of real need, facilities were either unavailable or unhygienic.

This is not a luxury issue. It is a matter of dignity.

For a site of such immense religious and cultural significance, the absence of adequate sanitation is unacceptable. If Sri Lanka is to meet its ambitious tourism targets, essential infrastructure, such as public toilets, must be prioritized immediately at Sri Pada and at all major tourist and pilgrimage sites.

Infrastructure strain is also evident in Ella, particularly around the iconic Nine Arches Bridge. While the attraction itself is breathtaking, access to the site is poorly suited to the sheer volume of visitors. We were required to walk up a steep, uneven slope to reach the railway lines—manageable for some, but certainly not ideal or safe for elderly visitors, families, or those with mobility challenges. With tourist numbers continuing to surge, access paths, safety measures, and crowd management urgently needs to be upgraded.

Missed opportunities and first impressions

Our visit to Yala National Park, particularly Block 5, was another missed opportunity. While the natural environment remains extraordinary, the overall experience did not meet expectations. Notably, our guide—experienced and deeply knowledgeable—offered several practical suggestions for improving visitor experience and conservation outcomes. Unfortunately, he also noted that such feedback often “falls on deaf ears.” Ignoring insights from those on the ground is a loss Sri Lanka can ill afford.

First impressions also matter, and this is where Bandaranaike International Airport still falls short. While recent renovations have improved the physical space, customs and immigration processes lack coherence during peak hours. Poorly formed queues, inconsistent enforcement, and inefficient passenger flow create unnecessary delays and frustration—often the very first experience visitors have of Sri Lanka.

Excellence exists—and the fundamentals must follow

That said, there is much to celebrate.

Our stays at several hotels, especially The Kingsbury, were outstanding. The service, hospitality, and quality of food were exceptional—on par with the best anywhere in the world. These experiences demonstrate that Sri Lanka already possesses the talent and capability to deliver excellence when systems and leadership align.

This contrast is precisely why the existing gaps are so frustrating: they are solvable.

Sri Lankans living overseas will always defend our country against unfair criticism and negative global narratives. But defending Sri Lanka does not mean remaining silent when basic standards are not met. True patriotism lies in constructive honesty.

If Sri Lanka is serious about welcoming the world, it must urgently address fundamentals: sanitation at sacred sites, safe access to major attractions, well-managed national parks, and efficient airport processes. These are not optional extras—they are the foundation of sustainable tourism.

This is not written in criticism, but in love. Sri Lanka deserves better, and so do the millions of visitors who come each year, eager to experience the beauty, spirituality, and warmth that our country offers so effortlessly.

The writer can be reached at Jerome.adparagraphams@gmail.com

By Jerome Adams

Features

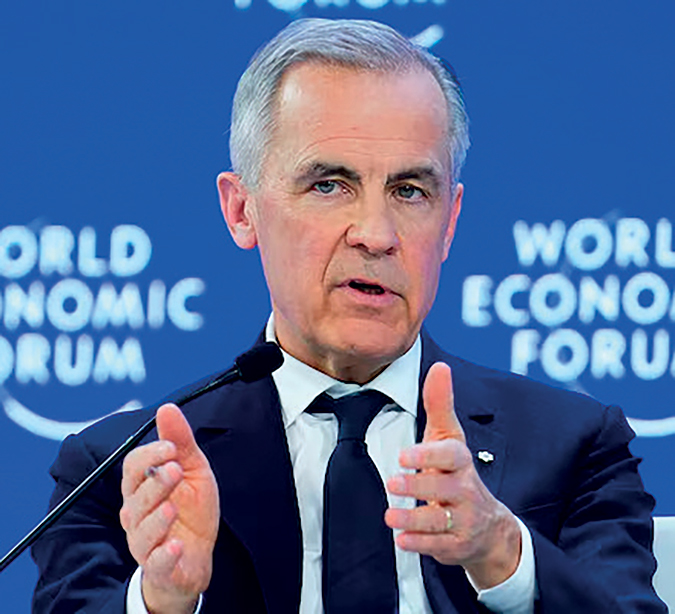

Seething Global Discontents and Sri Lanka’s Tea Cup Storms

Global temperatures in January have been polar opposite – plus 50 Celsius down under in Australia, and minus 45 Celsius up here in North America (I live in Canada). Between extremes of many kinds, not just thermal, the world order stands ruptured. That was the succinct message in what was perhaps the most widely circulated and listened to speeches of this century, delivered by Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney at Davos, in January. But all is not lost. Who seems to be getting lost in the mayhem of his own making is Donald Trump himself, the President of the United States and the world’s disruptor in chief.

After a year of issuing executive orders of all kinds, President Trump is being forced to retreat in Minneapolis, Minnesota, by the public reaction to the knee-jerk shooting and killing of two protesters in three weeks by federal immigration control and border patrol agents. The latter have been sent by the Administration to implement Trump’s orders for the arbitrary apprehension of anyone looking like an immigrant to be followed by equally arbitrary deportation.

The Proper Way

Many Americans are not opposed to deporting illegal and criminal immigrants, but all Americans like their government to do things the proper way. It is not the proper way in the US to send federal border and immigration agents to swarm urban neighbourhood streets and arrest neighbours among neighbours, children among other school children, and the employed among other employees – merely because they look different, they speak with an accent, or they are not carrying their papers on their person.

Americans generally swear by the Second Amendment and its questionably interpretive right allowing them to carry guns. But they have no tolerance when they see government forces turn their guns on fellow citizens. Trump and his administration cronies went too far and now the chickens are coming home to roost. Barely a month has passed in 2026, but Trump’s second term has already run into multiple storms.

There’s more to come between now and midterm elections in November. In the highly entrenched American system of checks and balances it is virtually impossible to throw a government out of office – lock, stock and barrel. Trump will complete his term, but more likely as a lame duck than an ordering executive. At the same time, the wounds that he has created will linger long even after he is gone.

Equally on the external front, it may not be possible to immediately reverse the disruptions caused by Trump after his term is over, but other countries and leaders are beginning to get tired of him and are looking for alternatives bypassing Trump, and by the same token bypassing the US. His attempt to do a Venezuela over Greenland has been spectacularly pushed back by a belatedly awakening Europe and America’s other western allies such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand. The wags have been quick to remind us that he is mostly a TACO (Trump always chickens out) Trump.

Grandiose Scheme or Failure

His grandiose scheme to establish a global Board of Peace with himself as lifetime Chair is all but becoming a starter. No country or leader of significant consequence has accepted the invitation. The motley collection of acceptors includes five East European countries, three Central Asian countries, eight Middle Eastern countries, two from South America, and four from Asia – Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia and Pakistan. The latter’s rush to join the club will foreclose any chance of India joining the Board. Countries are allowed a term of three years, but if you cough up $1 billion, could be member for life. Trump has declared himself to be lifetime chair of the Board, but he is not likely to contribute a dime. He might claim expenses, though. The Board of Peace was meant to be set up for the restoration of Gaza, but Trump has turned it into a retirement project for himself.

There is also the ridiculous absurdity of Trump continuing as chair even after his term ends and there is a different president in Washington. How will that arrangement work? If the next president turns out to be a Democrat, Trump may deny the US a seat on the board, cash or no cash. That may prove to be good for the UN and its long overdue restructuring. Although Trump’s Board has raised alarms about the threat it poses to the UN, the UN may end up being the inadvertent beneficiary of Trump’s mercurial madness.

The world is also beginning to push back on Trump’s tariffs. Rather, Trump’s tariffs are spurring other countries to forge new trade alliances and strike new trade deals. On Tuesday, India and EU struck the ‘mother of all’ trade deals between them, leaving America the poorer for it. Almost the next day , British Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer and Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced in Beijing that they had struck a string of deals on travel, trade and investments. “Not a Big Bang Free Trade Deal” yet, but that seems to be the goal. The Canadian Prime Minister has been globe-trotting to strike trade deals and create investment opportunities. He struck a good reciprocal deal with China, is looking to India, and has turned to South Korea and a consortium from Germany and Norway to submit bids for a massive submarine supply contract supplemented by investments in manufacturing and mineral industries. The informal first-right-of-refusal privilege that US had in Canada for defense contracts is now gone, thanks to Trump.

The disruptions that Trump has created in the world order may not be permanent or wholly irreversible, as Prime Minister Carney warned at Davos. But even the short term effects of Trump’s disruptions will be significant to all of US trading partners, especially smaller countries like Sri Lanka. Regardless of what they think of Trump, leaders of governments have a responsibility to protect their citizens from the negative effects of Trump’s tariffs. That will be in addition to everything else that governments have to do even if they do not have Trump’s disruptions to deal with.

Bland or Boisterous

Against the backdrop of Trump-induced global convulsions, politics in Sri Lanka is in a very stable mode. This is not to diminish the difficulties and challenges that the vast majority of Sri Lankans are facing – in meeting their daily needs, educating their children, finding employment for the youth, accessing timely health care and securing affordable care for the elderly. The challenges are especially severe for those devastated by cyclone Ditwah.

Politically, however, the government is not being tested by the opposition. And the once boisterous JVP/NPP has suddenly become ‘bland’ in government. “Bland works,” is a Canadian political quote coined by Bill Davis a nationally prominent premier of the Province of Ontario. Davis was responding to reporters looking for dramatic politics instead of boring blandness. He was Premier of Ontario for 14 years (1971-1985) and won four consecutive elections before retiring.

No one knows for how long the NPP government will be in power in Sri Lanka or how many more elections it is going to win, but there is no question that the government is singularly focused on winning the next parliamentary election, or both the presidential and parliamentary elections – depending on what happens to the system of directly electing the executive president.

The government is trying to grow comfortable in being on cruise control to see through the next parliamentary election. Its critics on the other hand, are picking on anything that happens on any day to blame or lampoon the government. The government for all its tight control of its members and messaging is not being able to put out quickly the fires that have been erupting. There are the now recurrent matters of the two AGs (non-appointment of the Auditor General and alleged attacks on the Attorney General) and the two ERs (Educational Reform and Electricity Reform), the timing of the PC elections, and the status of constitutional changes to end the system of directly electing the president.

There are also criticisms of high profile resignations due to government interference and questionable interdictions. Two recent resignations have drawn public attention and criticism, viz., the resignation of former Air Chief Marshal Harsha Abeywickrama from his position as the Chairman of Airport & Aviation Services, and the earlier resignation of Attorney-at-Law Ramani Jayasundara from her position as Chair of the National Women’s Commission. Both have been attributed to political interferences. In addition, the interdiction of the Deputy Secretary General of Parliament has also raised eyebrows and criticisms. The interdiction in parliament could not have come at a worse time for the government – just before the passing away of Nihal Seniviratne, who had served Sri Lanka’s parliament for 33 years and the last 13 of them as its distinguished Secretary General.

In a more political sense, echoes of the old JVP boisterousness periodically emanate in the statements of the JVP veteran and current Cabinet Minister K.D. Lal Kantha. Newspaper columnists love to pounce on his provocative pronouncements and make all manner of prognostications. Mr. Lal Kantha’s latest reported musing was that: “It is true our government is in power, but we still don’t have state power. We will bring about a revolution soon and seize state power as well.”

This was after he had reportedly taken exception to filmmaker Asoka Handagama’s one liner: “governing isn’t as easy as it looks when you are in the opposition,” and allegedly threatened to answer such jibes no matter who stood in the way and what they were wearing “black robes, national suits or the saffron.” Ironically, it was the ‘saffron part’ that allegedly led to the resignation of Harsha Abeywickrama from the Airport & Aviation Services. And President AKD himself has come under fire for his Thaipongal Day statement in Jaffna about Sinhala Buddhist pilgrims travelling all the way from the south to observe sil at the Tiisa Vihare in Thayiddy, Jaffna.

The Vihare has been the subject of controversy as it was allegedly built under military auspices on the property of local people who evacuated during the war. Being a master of the spoken word, the President could have pleaded with the pilgrims to show some sensitivity and empathy to the displaced Tamil people rather than blaming them (pilgrims) of ‘hatred.’ The real villains are those who sequestered property and constructed the building, and the government should direct its ire on them and not the pilgrims.

In the scheme of global things, Sri Lanka’s political skirmishes are still teacup storms. Yet it is never nice to spill your tea in public. Public embarrassments can be politically hurtful. As for Minister Lal Kantha’s distinction between governmental mandate and state power – this is a false dichotomy in a fundamentally practical sense. He may or may not be aware of it, but this distinction quite pre-occupied the ideologues of the 1970-75 United Front government. Their answer of appointing Permanent Secretaries from outside the civil service was hardly an answer, and in some instances the cure turned out to be worse than the disease.

As well, what used to be a leftist pre-occupation is now a right wing insistence especially in America with Trump’s identification of the so called ‘deep state’ as the enemy of the people. I don’t think the NPP government wants to go there. Rather, it should show creative originality in making the state, whether deep or shallow, to be of service to the people. There is a general recognition that the government has been doing just that in providing redress to the people impacted by the cyclone. A sign of that recognition is the number of people contributing to the disaster relief fund and in substantial amounts. The government should not betray this trust but build on it for the benefit of all. And better do it blandly than boisterously.

by Rajan Philips

Features

The historical context of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict

The themes of power-sharing, devolution, and federalism, which run through this work, have their origin in issues which are not connected to ethnicity. Indeed, federalism, as a structure of governance suited to Sri Lanka, was first proposed in an entirely different setting. At its inception, this had to do with the aspirations not of the Tamils, but of the Kandyan Sinhalese.

The Donoughmore Commission

A watershed in the Island’s constitutional development was the Donoughmore Commission which arrived on our shores in November, 1927. The Kandyan National Assembly, in their representations to the Commission, declared: “Ours is not a communal claim or a claim for the aggrandizement of a few. It is a claim of a nation to live its own life and realize its own destiny. A federal system will enable the respective nationals of the several states to prevent further inroads into their territories and to build up their own nationality.”

This had been foreshadowed during the years leading up to the appointment of the Donoughmore Commission by representations on similar lines by prominent Sinhala representatives of the Ceylon National Congress. An exemplar was S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, fresh from his 1laurels at Oxford, who, in a lecture delivered to the Students’ Congress in Jaffna on 17 July 1926, went so far as to characterize federalism as the “only solution to our political problems.” The lecture was the culmination of a line of argument which he had developed persuasively in six letters to The Ceylon Morning Leader, published between 19 May, and 30 June, 1926.

The Donoughmore Commissioners were not friendly to the idea of federalism because of their robust aversion to division along communal or other lines, and their commitment, as the foundation of their report, to unity of the body politic. A nuanced approach typified their recommendations, in so far as they showed themselves well disposed to the concept of Provincial Councils. They accepted the system in principle, although inclined to leave the modalities of implementation to an elected administration.

It is interesting to note that, almost a 100 years ago, the Donoughmore Commissioners showed sensitivity to a range of issues which gave rise to vigorous and even acrimonious debate in succeeding decades. Among these was a nexus between Provincial Councils and local government institutions, and the question whether Members of Parliament should be eligible to sit in Provincial Councils. On this latter issue, as recently as two years ago, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, citing copious precedents, strongly contended for the view that there should be no constitutional or statutory bar.

Incipient indications of ethnic identity emerging as an impediment to the growth of a healthy multi-party system proved to be a source of anxiety to the Donoughmore Commissioners. This accounted for their decision to spend several days in Jaffna and Batticaloa to listen to the views of a cross-section of the public there. Organizations which made representations to the Commission included the All Ceylon Tamil Congress and The Jaffna Association. The Commissioners were alive, as well, to burgeoning communal tensions within the Ceylon National Congress.

A Marxist-Leninist perspective

The impetus towards federalism had a strong ideological perspective, from a Marxist-Leninist standpoint. This was vividly mirrored in the policy articulated by the Ceylon Trade Union Federation on 23 September 1944, on which was built the constitutional proposals addressed by the Communist Party to the Ceylon National Congress on 18 October 1944. Subject to minor refinements and matters of detail, the two documents can be taken together. They go very far, indeed. Anticipating future developments, merger of the North East was specifically contemplated.

The nomenclature used had much in common with the current discourse. The Sinhalese and the Tamils were envisioned as two distinct “nations”, or “historically evolved nationalities”. The homeland concept found expression in relation to a contiguous territory. This was thought to be justified on the basis that the distinct nationalities “have their own language, economic life, culture, and psychological makeup.”

The high water mark of the proposals was the assertion that “Both nationalities have their right to self-determination, including the right, if they so desire, to form their own separate independent state.” The sheet anchor of the proposals was that the equality and sovereignty of the “peoples” of Ceylon must be recognized. These were among the ideas that found unanimous acceptance at the Town Hall rally on 15 October1944.

The Communist Party’s proposals not only gave expression to these normative principles, but spelt out practical means for arriving within the legislature. This was embodied in the proposal relating to two Chambers enjoying coeval authority. The Chamber of Representatives was to be elected on the basis of territorial constituencies buttressed by universal adult franchise, while the second Chamber, designated the Chamber of Nationalities, was marked by the special feature of the principle of equality between the nationalities.

These proposals received further elaboration in a memorandum submitted to the Working Committee of the Ceylon National Congress by two prominent members of the Communist Party, Mr. Pieter Keuneman and Mr. A. Vaidialingam. The thrust of their reasoning was predicated on a multinational state with inbuilt safeguards for the “non- dominant nationality”. The premise was set out pithily as follows: “We regard a nation as a historical, as opposed to an ethnographical, concept. It is a historically evolved, stable community of people living in a contiguous territory as their traditional homeland.”

The Soulbury Commission

These events occurred in the immediate backdrop to the transition from colonial to dominion status. A Commission headed by Lord Soulbury, appointed by Whitehall to consider the grant of full independence to Ceylon, arrived in the country in December, 1944. The main focus of their work was intended to be a comprehensive set of proposals prepared by the Board of Ministers, which functioned under the Donoughmore Constitution. This was in response to the Declaration of May, 1943, made by Mr. Oliver Stanley, Secretary of State for the Colonies, setting out, in outline, the intentions of the British government.

Some degree of friction arose, however, because of the subsequent exhortation to the Soulbury Commission “to consult with various interests including minority communities” interpreted by the Board of Ministers as a breach of faith, in that it deviated from the previous assurance that the Commission’s mandate would be confined to consideration of the Memorandum to be submitted by the Ministers. It was possible, however, to arrive at a pragmatic compromise, in terms of which the Ministers, although boycotting formal sessions with the Commission, made their views known extensively during frequent social interactions.

Their proposals were contained in the ‘Ministers’ draft’, which was mainly the work of Sir Ivor Jennings, a renowned constitutional expert, later to become Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ceylon, in close consultation with Mr D. S. Senanayake and Sir Oliver Goonetilleke. The report of the Soulbury Commission, based primarily on the Ministers’ draft, was published in 1945 as a White Paper, which formed the foundation of the three legal instruments comprising the Constitution of Ceylon of 1948.

An interesting feature of the work of the Soulbury Commission was explicit recognition of the complexity of inter-communal relations on the Island and the near- insoluble difficulties they posed in respect of constitutional development. The Commission showed candour in its observation that “The relations of the minorities – the Ceylon Tamils, the Indian Tamils, Muslims, Burghers, and Europeans with the Sinhalese majority – present the most difficult of the many problems involved in the reform of the Constitution of Ceylon.”

The Soulbury Commission found itself subject to rival pressures of the greatest intensity. The Board of Ministers had graduated from their efforts directed at amendment of the Donoughmore Constitution to a full-blooded demand for dominion status. The countervailing pressure came from the leadership of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress, which strenuously contendedc omplete transference of power and authority from neutral British hands to the people of this country is causing, in the minds of the Tamil people, “in common with other minorities, much misgiving and fear.”

The most significant aspect of the Soulbury Commission’s initiatives consisted of the search for mediating techniques to discourage polarization. On the whole, this effort was marked by commendable pragmatism. It is of interest that the Commissioners, invited to consider in earnest the federal route, had little fascination for it, nor did the idea of a Bill of Rights find favour with them. If the underlying fear related to encroachment of seminal rights by capricious legislative action, this anxiety could have been convincingly assuaged by enshrining in the Constitution a nucleus of rights placed beyond the reach of the legislature.

This expedient would have been effective, if combined with appropriate mechanisms of judicial review. In line with this approach, it would be an important part of the judicial function, exercised by the Apex Court, to rule on the issue of incompatibility of impugned legislation with paramount safeguards embodied in the Constitution.

The Soulbury Commissioners were not persuaded of the wisdom of this course of action, and shied away from support for comprehensive judicial review as a protective lever. Their preference was for less intrusive mechanisms. At that stage of constitutional evolution, it seemed to them that adequate protection could be conferred on minority communities by the combination of two sets of safeguards. The first had to do with the numerical strength of minority representation in Parliament. The main plank of the submission in this regard by the Tamil-speaking leadership resided in a distinction between an absolute and a relative majority.

The gist of the argument was that the majority community, although admittedly in the legislature, should not be possessed of sufficient strength to override all minority representatives, taken together. With this end in view, Mr. G. G. Ponnambalam, leader of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress, argued strenuously for the 50-50 formula, in terms of which all minority communities collectively would be entitled to 50% representation, complemented by proportionate representation in the Cabinet of Ministers, as well. This was urged as the only realistic buffer against communal hegemony.

The extreme dimensions of this proposal held no appeal to the Soulbury Commissioners. Conceding as they did the gravity of the issue, they opted for a more moderate solution. This took the form of a proposed electoral system, at the base of which lay a mixture of population-based and territorial criteria. The basic character of the system involved the election of members relative to spread of population, subject however to the refinement that four additional members each were to be allocated to the Northern and Eastern Provinces, over and above their entitlement on the population-centric criteria.

The intention was to make provision in some form for “additional weightage in the interest of equity underpinning the electoral system, as a whole. This fell far short of the ambitious claim by the Tamil leadership for “balanced representation”, which entailed a mechanism to forestall a permanent Sinhala majority, with the probable risk of unbridled majoritarianism. The markedly limited scope of the suggested modality met with disillusionment on the part of the Tamil leadership. It was, nevertheless, not a stand-alone formula.

It stood in conjunction with a carefully crafted constitutional limitation on the legislative competence of Parliament. The legislature was expressly precluded from making any law, the effect of which was to “make persons of any community or religion liable to disabilities or restrictions to which persons of other made liable”, or “confer on persons of any community or religion any privilege or advantage which is not conferred on persons of other communities or religions”. Any law contravening this prohibition was characterized as void. The provision against discrimination, couched in this form, was susceptible to being overridden by a vote of two-thirds of the total membership of Parliament.

(To be continued next week)

(Excerpted from The Sri Lanka Peace Process: An Inside View by GL Peiris)

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Editorial1 day ago

Editorial1 day agoGovt. provoking TUs