Features

The Chinese ‘Debt Trap’ is a myth

Chinese firms are not the only companies to benefit from Chinese-financed projects. Perhaps no country was more alarmed by Hambantota than India, the regional giant that several times rebuffed Sri Lanka’s appeals for investment, aid, and equity partnerships.

The narrative wrongfully portrays both Beijing and the developing countries it deals with

by DEBORAH BRAUTIGAM and

MEG RITHMIRE

The atlantic

China, we are told, inveigles poorer countries into taking out loan after loan to build expensive infrastructure that they can’t afford and that will yield few benefits, all with the end goal of Beijing eventually taking control of these assets from its struggling borrowers. As states around the world pile on debt to combat the coronavirus pandemic and bolster flagging economies, fears of such possible seizures have only amplified.

Seen this way, China’s internationalization—as laid out in programmes such as the Belt and Road Initiative—is not simply a pursuit of geopolitical influence but also, in some tellings, a weapon. Once a country is weighed down by Chinese loans, like a hapless gambler who borrows from the Mafia, it is Beijing’s puppet and in danger of losing a limb.

The prime example of this is the Sri Lankan port of Hambantota. As the story goes, Beijing pushed Sri Lanka into borrowing money from Chinese banks to pay for the project, which had no prospect of commercial success. Onerous terms and feeble revenues eventually pushed Sri Lanka into default, at which point Beijing demanded the port as collateral, forcing the Sri Lankan government to surrender control to a Chinese firm.

The Trump administration pointed to Hambantota to warn of China’s strategic use of debt: In 2018, former Vice President Mike Pence called it “debt-trap diplomacy”—a phrase he used through the last days of the administration—and evidence of China’s military ambitions. Last year, erstwhile Attorney General William Barr raised the case to argue that Beijing is “loading poor countries up with debt, refusing to renegotiate terms, and then taking control of the infrastructure itself.”

As Michael Ondaatje, one of Sri Lanka’s greatest chroniclers, once said, “In Sri Lanka a well-told lie is worth a thousand facts.” And the debt-trap narrative is just that: a lie, and a powerful one.

Our research shows that Chinese banks are willing to restructure the terms of existing loans and have never actually seized an asset from any country, much less the port of Hambantota. A Chinese company’s acquisition of a majority stake in the port was a cautionary tale, but it’s not the one we’ve often heard. With a new administration in Washington, the truth about the widely, perhaps willfully, misunderstood case of Hambantota Port is long overdue.

The city of Hambantota lies at the southern tip of Sri Lanka, a few nautical miles from the busy Indian Ocean shipping lane that accounts for nearly all of the ocean-borne trade between Asia and Europe, and more than 80 percent of ocean-borne global trade. When a Chinese firm snagged the contract to build the city’s port, it was stepping into an ongoing Western competition, though one the United States had largely abandoned.

It was the Canadian International Development Agency—not China—that financed Canada’s leading engineering and construction firm, SNC-Lavalin, to carry out a feasibility study for the port. We obtained more than 1,000 pages of documents detailing this effort through a Freedom of Information Act request. The study, concluded in 2003, confirmed that building the port at Hambantota was feasible, and supporting documents show that the Canadians’ greatest fear was losing the project to European competitors. SNC-Lavalin recommended that it be undertaken through a joint-venture agreement between the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) and a “private consortium” on a build-own-operate-transfer basis, a type of project in which a single company receives a contract to undertake all the steps required to get such a port up and running, and then gets to operate it when it is.

The Canadian project failed to move forward, mostly because of the vicissitudes of Sri Lankan politics. But the plan to build a port in Hambantota gained traction during the rule of the Rajapaksas—Mahinda Rajapaksa, who served as President from 2005 through 2015, and his brother Gotabaya, the current President and former Minister of Defence—who grew up in Hambantota. They promised to bring big ships to the region, a call that gained urgency after the devastating 2004 tsunami pulverized Sri Lanka’s coast and the local economy.

We reviewed a second feasibility report, produced in 2006 by the Danish engineering firm Ramboll, that made similar recommendations to the plans put forward by SNC-Lavalin, arguing that an initial phase of the project should allow for the transport of non-containerized cargo—oil, cars, grain—to start bringing in revenue, before expanding the port to be able to handle the traffic and storage of traditional containers. By then, the port in the capital city of Colombo, a 100 miles away and consistently one of the world’s busiest, had just expanded and was already pushing capacity. The Colombo port, however, was smack in the middle of the city, while Hambantota had a hinterland, meaning it offered greater potential for expansion and development.

(Read: The undoing of China’s economic miracle)

To look at a map of the Indian Ocean region at the time was to see opportunity and expanding middle classes everywhere. Families in India and across Africa were demanding more consumer goods from China. Countries such as Vietnam were growing rapidly and would need more natural resources. To justify its existence, the port in Hambantota would have to secure only a fraction of the cargo that went through Singapore, the world’s busiest transshipment port.

Armed with the Ramboll report, Sri Lanka’s government approached the United States and India; both countries said no. But a Chinese construction firm, China Harbour Group, had learned about Colombo’s hopes, and lobbied hard for the project. China Eximbank agreed to fund it, and China Harbour won the contract.

This was in 2007, six years before Xi Jinping introduced the Belt and Road Initiative. Sri Lanka was still in the last, and bloodiest, phase of its long civil war, and the world was on the verge of a financial crisis. The details are important: China Eximbank offered a $307 million, 15-year commercial loan with a four-year grace period, offering Sri Lanka a choice between a 6.3 percent fixed interest rate or one that would rise or fall depending on LIBOR, a floating rate. Colombo chose the former, conscious that global interest rates were trending higher during the negotiations and hoping to lock in what it thought would be favourable terms. Phase I of the port project was completed on schedule within three years.

For a conflict-torn country that struggled to generate tax revenue, the terms of the loan seemed reasonable. As Saliya Wickramasuriya, the former chairman of the SLPA, told us, “To get commercial loans as large as $300 million during the war was not easy.” That same year, Sri Lanka also issued its first international bond, with an interest rate of 8.25 percent. Both decisions would come back to haunt the government.

Finally, in 2009, after decades of violence, Sri Lanka’s civil war came to an end. Buoyed by the victory, the government embarked on a debt-financed push to build and improve the country’s infrastructure. Annual economic growth rates climbed to 6 percent, but Sri Lanka’s debt burden soared as well.

In Hambantota, instead of waiting for phase 1 of the port to generate revenue as the Ramboll team had recommended, Mahinda Rajapaksa pushed ahead with phase 2, transforming Hambantota into a container port. In 2012, Sri Lanka borrowed another $757 million from China Eximbank, this time at a reduced, post-financial-crisis interest rate of 2 percent. Rajapaksa took the liberty of naming the port after himself.

By 2014, Hambantota was losing money. Realizing that they needed more experienced operators, the SLPA signed an agreement with China Harbour and China Merchants Group to have them jointly develop and operate the new port for 35 years. China Merchants was already operating a new terminal in the port in Colombo, and China Harbour had invested $1.4 billion in Colombo Port City, a lucrative real-estate project involving land reclamation. But while the lawyers drew up the contracts, a political upheaval was taking shape.

Rajapaksa called a surprise election for January 2015 and in the final months of the campaign, his own Health Minister, Maithripala Sirisena, decided to challenge him. Like opposition candidates in Malaysia, the Maldives, and Zambia, the incumbent’s financial relations with China and allegations of corruption made for potent campaign fodder. To the country’s shock, and perhaps his own, Sirisena won.

Steep payments on international sovereign bonds, which comprised nearly 40 percent of the country’s external debt, put Sirisena’s government in dire fiscal straits almost immediately. When Sirisena took office, Sri Lanka owed more to Japan, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank than to China. Of the $4.5 billion in debt service Sri Lanka would pay in 2017, only 5 percent was because of Hambantota. The Central Bank governors under both Rajapaksa and Sirisena do not agree on much, but they both told us that Hambantota, and Chinese finance in general, was not the source of the country’s financial distress.

There was also never a default. Colombo arranged a bailout from the International Monetary Fund, and decided to raise much-needed dollars by leasing out the underperforming Hambantota Port to an experienced company—just as the Canadians had recommended. There was not an open tender, and the only two bids came from China Merchants and China Harbour; Sri Lanka chose China Merchants, making it the majority shareholder with a 99-year lease, and used the $1.12 billion cash infusion to bolster its foreign reserves, not to pay off China Eximbank.

(Read: How Xi Jinping blew it)

Before the port episode, “Sri Lanka could sink into the Indian Ocean and most of the Western world wouldn’t notice,” Subhashini Abeysinghe, Research Director at Verité Research, an independent Colombo-based think tank, told us. Suddenly, the island nation featured prominently in foreign-policy speeches in Washington. Pence voiced worry that Hambantota could become a “forward military base” for China.

Yet Hambantota’s location is strategic only from a business perspective: The port is cut into the coast to avoid the Indian Ocean’s heavy swells, and its narrow channel allows only one ship to enter or exit at a time, typically with the aid of a tugboat. In the event of a military conflict, naval vessels stationed there would be proverbial fish in a barrel.

The notion of “debt-trap diplomacy” casts China as a conniving creditor and countries, such as Sri Lanka, as its credulous victims. On a closer look, however, the situation is far more complex. China’s march outward, like its domestic development, is probing and experimental, a learning process marked by frequent adjustment. After the construction of the port in Hambantota, for example, Chinese firms and banks learned that strongmen fall and that they’d better have strategies for dealing with political risk. They’re now developing these strategies, getting better at discerning business opportunities and withdrawing where they know they can’t win. Still, American leaders and thinkers from both sides of the aisle give speeches about China’s “modern-day colonialism.”

Over the past 20 years, Chinese firms have learned a lot about how to play in an international construction business that remains dominated by Europe: Whereas China has 27 firms among the top 100 global contractors, up from nine in 2000, Europe has 37, down from 41. The U.S. has seven, compared to 19 two decades ago.

Chinese firms are not the only companies to benefit from Chinese-financed projects. Perhaps no country was more alarmed by Hambantota than India, the regional giant that several times rebuffed Sri Lanka’s appeals for investment, aid, and equity partnerships. Yet an Indian-led business, Meghraj, joined the U.K.-based engineering firm Atkins Limited in an international consortium to write the long-term plan for Hambantota Port and for the development of a new business zone. The French firms Bolloré and CMA-CGM have partnered with China Merchants and China Harbour in port developments in Nigeria, Cameroon, and elsewhere.

The other side of the debt-trap myth involves debtor countries. Places such as Sri Lanka—or, for that matter, Kenya, Zambia, or Malaysia—are no stranger to geopolitical games. And they’re irked by American views that they’ve been so easily swindled. As one Malaysian politician remarked to us, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss how Chinese finance featured in that country’s political drama, “Can’t the U.S. State Department tell the difference between campaign rhetoric that our opponents are slaves to China and actually being slaves to China?”

The events that led to a Chinese company’s acquisition of a majority stake in a Sri Lankan port reveal a great deal about how our world is changing. China and other countries are becoming more sophisticated in bargaining with one another. And it would be a shame if the U.S. fails to learn alongside them.

DEBORAH BRAUTIGAM is Bernard L. Schwartz Professor of International Political Economy at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University

MEG RITHMIRE is F. Warren McFarlan Associate Professor at Harvard Business School.

Features

Australia’s social media ban: A sledgehammer approach to a scalpel problem

When governments panic, they legislate. When they legislate in panic, they create monsters. Australia’s world-first ban on social media for under-16s, which came into force on 10 December, 2025, is precisely such a monster, a clumsy, authoritarian response to a legitimate problem that threatens to do more harm than good.

When governments panic, they legislate. When they legislate in panic, they create monsters. Australia’s world-first ban on social media for under-16s, which came into force on 10 December, 2025, is precisely such a monster, a clumsy, authoritarian response to a legitimate problem that threatens to do more harm than good.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese hailed it as a “proud day” for Australian families. One wonders what there is to be proud about when a liberal democracy resorts to blanket censorship, violates children’s fundamental rights, and outsources enforcement to the very tech giants it claims to be taming. This is not protection; it is political theatre masquerading as policy.

The Seduction of Simplicity

The ban’s appeal is obvious. Social media platforms have become toxic playgrounds where children are subjected to cyberbullying, addictive algorithms, and content that can genuinely harm their mental health. The statistics are damning: 40% of Australian teens have experienced cyberbullying, youth self-harm hospital admissions rose 47% between 2012 and 2022, and depression rates have skyrocketed in tandem with smartphone adoption. These are real problems demanding real solutions.

But here’s where Australia has gone catastrophically wrong: it has conflated correlation with causation and chosen punishment over education, restriction over reform, and authoritarian control over empowerment. The ban assumes that removing children from social media will magically solve mental health crises, as if these platforms emerged in a vacuum rather than as symptoms of deeper societal failures, inadequate mental health services, overworked parents, underfunded schools, and a culture that has outsourced child-rearing to screens.

Dr. Naomi Lott of the University of Reading hit the nail on the head when she argued that the ban unfairly burdens youth for tech firms’ failures in content moderation and algorithm design. Why should children pay the price for corporate malfeasance? This is akin to banning teenagers from roads because car manufacturers built unsafe vehicles, rather than holding those manufacturers accountable.

The Enforcement Farce

The practical implementation of this ban reads like dystopian satire. Platforms must take “reasonable steps” to prevent access, a phrase so vague it could mean anything or nothing. The age verification methods being deployed include AI-driven facial recognition, behavioural analysis, government ID scans, and something called “AgeKeys.” Each comes with its own Pandora’s box of problems.

Facial recognition technology has well-documented biases against ethnic minorities. Behavioural analysis can be easily gamed by tech-savvy teenagers. ID scans create massive privacy risks in a country that has suffered repeated data breaches. And zero-knowledge proof, while theoretically elegant, require a level of technical sophistication that makes them impractical for mass adoption.

Already, teenagers are bragging online about circumventing the restrictions, prompting Albanese’s impotent rebuke. What did he expect? That Australian youth would simply accept digital exile? The history of prohibition, from alcohol to file-sharing, teaches us that determined users will always find workarounds. The ban doesn’t eliminate risk; it merely drives it underground where it becomes harder to monitor and address.

Even more absurdly, platforms like YouTube have expressed doubts about enforcement, and Opposition Leader Sussan Ley has declared she has “no confidence” in the ban’s efficacy. When your own political opposition and the companies tasked with implementing your policy both say it won’t work, perhaps that’s a sign you should reconsider.

The Rights We’re Trading Away

The legal challenges now percolating through Australia’s High Court get to the heart of what’s really at stake here. The Digital Freedom Project, led by teenagers Noah Jones and Macy Neyland, argues that the ban violates the implied constitutional freedom of political communication. They’re right. Social media platforms, for all their flaws, have become essential venues for democratic discourse. By age 16, many young Australians are politically aware, engaged in climate activism, and participating in public debates. This ban silences them.

The government’s response, that child welfare trumps absolute freedom, sounds reasonable until you examine it closely. Child welfare is being invoked as a rhetorical trump card to justify what is essentially state paternalism. The government isn’t protecting children from objective harm; it’s making a value judgment about what information they should be allowed to access and what communities they should be permitted to join. That’s thought control, not child protection.

Moreover, the ban creates a two-tiered system of rights. Those over 16 can access platforms; those under cannot, regardless of maturity, need, or circumstance. A 15-year-old seeking LGBTQ+ support groups, mental health resources, or information about escaping domestic abuse is now cut off from potentially life-saving communities. A 15-year-old living in rural Australia, isolated from peers, loses a vital social lifeline. The ban is blunt force trauma applied to a problem requiring surgical precision.

The Privacy Nightmare

Let’s talk about the elephant in the digital room: data security. Australia’s track record here is abysmal. The country has experienced multiple high-profile data breaches, and now it’s mandating that platforms collect biometric data, government IDs, and behavioural information from millions of users, including adults who will need to verify their age to distinguish themselves from banned minors.

The legislation claims to mandate “data minimisation” and promises that information collected solely for age verification will be destroyed post-verification. These promises are worth less than the pixels they’re displayed on. Once data is collected, it exists. It can be hacked. It can be subpoenaed. It can be repurposed. The fine for violations, up to AUD 9.5 million, sounds impressive until you realise that’s pocket change for tech giants making billions annually.

We’re creating a massive honeypot of sensitive information about children and families, and we’re trusting companies with questionable data stewardship records to protect it. What could possibly go wrong?

The Global Domino Delusion

Proponents like US Senator Josh Hawley and author Jonathan Haidt praise Australia’s ban as a “bold precedent” that will trigger global reform. This is wishful thinking bordering on delusion. What Australia has actually created is a case study in how not to regulate technology.

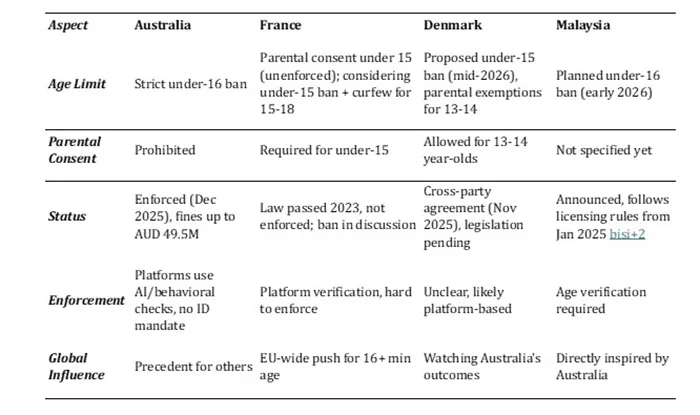

France, Denmark, and Malaysia are watching, but with notable differences. France’s model includes parental consent options. Denmark proposes exemptions for 13-14-year-olds with parental approval. These approaches recognise what Australia refuses to acknowledge: that blanket prohibitions fail to account for individual circumstances and family autonomy.

The comparison table in the document reveals the stark rigidity of Australia’s approach. It’s the only country attempting outright prohibition without parental consent. This isn’t leadership; it’s extremism. Other nations may cherry-pick elements of Australia’s approach while avoiding its most draconian features. (See Table)

The Real Solutions We’re Ignoring

Here’s what actual child protection would look like: holding platforms legally accountable for algorithmic harm, mandating transparent content moderation, requiring platforms to offer chronological feeds instead of engagement-maximising algorithms, funding digital literacy programmes in schools, properly resourcing mental health services for young people, and empowering parents with better tools to guide their children’s online experiences.

Instead, Australia has chosen the path of least intellectual effort: ban it and hope for the best. This is governance by bumper sticker, policy by panic.

Mia Bannister, whose son’s suicide has been invoked repeatedly to justify the ban, called parental enforcement “short-term pain, long-term gain” and urged families to remove devices entirely. But her tragedy, however heart-wrenching, doesn’t justify bad policy. Individual cases, no matter how emotionally compelling, are poor foundations for sweeping legislation affecting millions.

Conclusion: The Tyranny of Good Intentions

Australia’s social media ban is built on good intentions, genuine concerns about child welfare, and understandable frustration with unaccountable tech giants. But good intentions pave a very particular road, and this road leads to a place where governments dictate what information citizens can access based on age, where privacy becomes a quaint relic, and where young people are infantilised rather than educated.

The ban will fail on its own terms, teenagers will circumvent it, platforms will struggle with enforcement, and the mental health crisis will continue because it was never primarily about social media. But it will succeed in normalising digital authoritarianism, expanding surveillance infrastructure, and teaching young Australians that their rights are negotiable commodities.

When this ban inevitably fails, when the promised mental health improvements don’t materialize, when data breaches expose the verification systems, and when teenagers continue to access prohibited platforms through VPNs and workarounds, Australia will face a choice: double down on enforcement, creating an even more invasive surveillance state, or admit that the entire exercise was a costly mistake.

Smart money says they’ll choose the former. After all, once governments acquire new powers, they rarely relinquish them willingly. And that’s the real danger here, not that Australia will fail to protect children from social media, but that it will succeed in building the infrastructure for a far more intrusive state. The platforms may be the proximate target, but the ultimate casualties will be freedom, privacy, and trust.

Australia didn’t need a world-first ban. It needed world-class thinking. Instead, it settled for a world of trouble.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Sustaining good governance requires good systems

A prominent feature of the first year of the NPP government is that it has not engaged in the institutional reforms which was expected of it. This observation comes in the context of the extraordinary mandate with which the government was elected and the high expectations that accompanied its rise to power. When in opposition and in its election manifesto, the JVP and NPP took a prominent role in advocating good governance systems for the country. They insisted on constitutional reform that included the abolition of the executive presidency and the concentration of power it epitomises, the strengthening of independent institutions that overlook key state institutions such as the judiciary, public service and police, and the reform or repeal of repressive laws such as the PTA and the Online Safety Act.

The transformation of a political party that averaged between three to five percent of the popular vote into one that currently forms the government with a two thirds majority in parliament is a testament to the faith that the general population placed in the JVP/ NPP combine. This faith was the outcome of more than three decades of disciplined conduct in the aftermath of the bitter experience of the 1988 to 1990 period of JVP insurrection. The manner in which the handful of JVP parliamentarians engaged in debate with well researched critiques of government policy and actions, and their service in times of disaster such as the tsunami of 2004 won them the trust of the people. This faith was bolstered by the Aragalaya movement which galvanized the citizens against the ruling elites of the past.

In this context, the long delay to repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act which has earned notoriety for its abuse especially against ethnic and religious minorities, has been a disappointment to those who value human rights. So has been the delay in appointing an Auditor General, so important in ensuring accountability for the money expended by the state. The PTA has a long history of being used without restraint against those deemed to be anti-state which, ironically enough, included the JVP in the period 1988 to 1990. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), published in December 2025, is the latest attempt to repeal and replace the PTA. Unfortunately, the PSTA largely replicates the structure, logic and dangers of previous failed counter terrorism bills, including the Counter Terrorism Act of 2018 and the Anti Terrorism Act proposed in 2023.

Misguided Assumption

Despite its stated commitment to rule of law and fundamental rights, the draft PTSA reproduces many of the core defects of the PTA. In a preliminary statement, the Centre for Policy Alternatives has observed among other things that “if there is a Detention Order made against the person, then in combination, the period of remand and detention can extend up to two years. This means that a person can languish in detention for up to two years without being charged with a crime. Such a long period again raises questions of the power of the State to target individuals, exacerbated by Sri Lanka’s history of long periods of remand and detention, which has contributed to abuse and violence.” Human Rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal has warned against the broad definition of terrorism under the proposed law: “The definition empowers state officials to term acts of dissent and civil disobedience as ‘terrorism’ and will lawfully permit disproportionate and excessive responses.” The legitimate and peaceful protests against abuse of power by the authorities cannot be classified as acts of terror.

The willingness to retain such powers reflects the surmise that the government feels that keeping in place the structures that come from the past is to their benefit, as they can utilise those powers in a crisis. Due to the strict discipline that exists within the JVP/NPP at this time there may be an assumption that those the party appoints will not abuse their trust. However, the country’s experience with draconian laws designed for exceptional circumstances demonstrates that they tend to become tools of routine governance. On the plus side, the government has given two months for public comment which will become meaningful if the inputs from civil society actors are taken into consideration.

Worldwide experience has repeatedly demonstrated that integrity at the level of individual leaders, while necessary, is not sufficient to guarantee good governance over time. This is where the absence of institutional reform becomes significant. The aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah in particular has necessitated massive procurements of emergency relief which have to be disbursed at maximum speed. There are also significant amounts of foreign aid flowing into the country to help it deal with the relief and recovery phase. There are protocols in place that need to be followed and monitored so that a fiasco like the disappearance of tsunami aid in 2004 does not recur. To the government’s credit there are no such allegations at the present time. But precautions need to be in place, and those precautions depend less on trust in individuals than on the strength and independence of oversight institutions.

Inappropriate Appointments

It is in this context that the government’s efforts to appoint its own preferred nominees to the Auditor General’s Department has also come as a disappointment to civil society groups. The unsuitability of the latest presidential nominee has given rise to the surmise that this nomination was a time buying exercise to make an acting appointment. For the fourth time, the Constitutional Council refused to accept the president’s nominee. The term of the three independent civil society members of the Constitutional Council ends in January which would give the government the opportunity to appoint three new members of its choice and get its way in the future.

The failure to appoint a permanent Auditor General has created an institutional vacuum at a critical moment. The Auditor General acts as a watchdog, ensuring effective service delivery promoting integrity in public administration and providing an independent review of the performance and accountability. Transparency International has observed “The sequence of events following the retirement of the previous Auditor General points to a broader political inertia and a governance failure. Despite the clear constitutional importance of the role, the appointment process has remained protracted and opaque, raising serious questions about political will and commitment to accountability.”

It would appear that the government leadership takes the position they have been given the mandate to govern the country which requires implementation by those they have confidence in. This may explain their approach to the appointment (or non-appointment) at this time of the Auditor General. Yet this approach carries risks. Institutions are designed to function beyond the lifespan of any one government and to protect the public interest even when those in power are tempted to act otherwise. The challenge and opportunity for the NPP government is to safeguard independent institutions and enact just laws, so that the promise of system change endures beyond personalities and political cycles.

by Jehan Perera

Features

General education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

General education reform presents an opportunity to explore ways to promote social and ethnic cohesion. A school curriculum could foster shared values, empathy, and critical thinking, through social studies and civics education, implement inclusive language policies, and raise critical awareness about our collective histories. Yet, the government’s new policy document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025, leaves us little to look forward to in this regard.

The policy document points to several “salient” features within it, including: 1) a school credit system to quantify learning; 2) module-based formative and summative assessments to replace end-of-term tests; 3) skills assessment in Grade 9 consisting of a ‘literacy and numeracy test’ and a ‘career interest test’; 4) a comprehensive GPA-based reporting system spanning the various phases of education; 5) blended learning that combines online with classroom teaching; 6) learning units to guide students to select their preferred career pathways; 7) technology modules; 8) innovation labs; and 9) Early Childhood Education (ECE). Notably, social and ethnic cohesion does not appear in this list. Here, I explore how the proposed curriculum reforms align (or do not align) with the NPP’s pledge to inculcate “[s]afety, mutual understanding, trust and rights of all ethnicities and religious groups” (p.127), in their 2024 Election Manifesto.

Language/ethnicity in the present curriculum

The civil war ended over 15 years ago, but our general education system has done little to bring ethnic communities together. In fact, most students still cannot speak in the “second national language” (SNL) and textbooks continue to reinforce negative stereotyping of ethnic minorities, while leaving out crucial elements of our post-independence history.

Although SNL has been a compulsory subject since the 1990s, the hours dedicated to SNL are few, curricula poorly developed, and trained teachers few (Perera, 2025). Perhaps due to unconscious bias and for ideological reasons, SNL is not valued by parents and school communities more broadly. Most students, who enter our Faculty, only have basic reading/writing skills in SNL, apart from the few Muslim and Tamil students who schooled outside the North and the East; they pick up SNL by virtue of their environment, not the school curriculum.

Regardless of ethnic background, most undergraduates seem to be ignorant about crucial aspects of our country’s history of ethnic conflict. The Grade 11 history textbook, which contains the only chapter on the post-independence period, does not mention the civil war or the events that led up to it. While the textbook valourises ‘Sinhala Only’ as an anti-colonial policy (p.11), the material covering the period thereafter fails to mention the anti-Tamil riots, rise of rebel groups, escalation of civil war, and JVP insurrections. The words “Tamil” and “Muslim” appear most frequently in the chapter, ‘National Renaissance,’ which cursorily mentions “Sinhalese-Muslim riots” vis-à-vis the Temperance Movement (p.57). The disenfranchisement of the Malaiyaha Tamils and their history are completely left out.

Given the horrifying experiences of war and exclusion experienced by many of our peoples since independence, and because most students still learn in mono-ethnic schools having little interaction with the ‘Other’, it is not surprising that our undergraduates find it difficult to mix across language and ethnic communities. This environment also creates fertile ground for polarizing discourses that further divide and segregate students once they enter university.

More of the same?

How does Transforming General Education seek to address these problems? The introduction begins on a positive note: “The proposed reforms will create citizens with a critical consciousness who will respect and appreciate the diversity they see around them, along the lines of ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, and other areas of difference” (p.1). Although National Education Goal no. 8 somewhat problematically aims to “Develop a patriotic Sri Lankan citizen fostering national cohesion, national integrity, and national unity while respecting cultural diversity (p. 2), the curriculum reforms aim to embed values of “equity, inclusivity, and social justice” (p. 9) through education. Such buzzwords appear through the introduction, but are not reflected in the reforms.

Learning SNL is promoted under Language and Literacy (Learning Area no. 1) as “a critical means of reconciliation and co-existence”, but the number of hours assigned to SNL are minimal. For instance, at primary level (Grades 1 to 5), only 0.3 to 1 hour is allocated to SNL per week. Meanwhile, at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), out of 35 credits (30 credits across 15 essential subjects that include SNL, history and civics; 3 credits of further learning modules; and 2 credits of transversal skills modules (p. 13, pp.18-19), SNL receives 1 credit (10 hours) per term. Like other essential subjects, SNL is to be assessed through formative and summative assessments within modules. As details of the Grade 9 skills assessment are not provided in the document, it is unclear whether SNL assessments will be included in the ‘Literacy and numeracy test’. At senior secondary level – phase 1 (Grades 10-11 – O/L equivalent), SNL is listed as an elective.

Refreshingly, the policy document does acknowledge the detrimental effects of funding cuts in the humanities and social sciences, and highlights their importance for creating knowledge that could help to “eradicate socioeconomic divisions and inequalities” (p.5-6). It goes on to point to the salience of the Humanities and Social Sciences Education under Learning Area no. 6 (p.12):

“Humanities and Social Sciences education is vital for students to develop as well as critique various forms of identities so that they have an awareness of their role in their immediate communities and nation. Such awareness will allow them to contribute towards the strengthening of democracy and intercommunal dialogue, which is necessary for peace and reconciliation. Furthermore, a strong grounding in the Humanities and Social Sciences will lead to equity and social justice concerning caste, disability, gender, and other features of social stratification.”

Sadly, the seemingly progressive philosophy guiding has not moulded the new curriculum. Subjects that could potentially address social/ethnic cohesion, such as environmental studies, history and civics, are not listed as learning areas at the primary level. History is allocated 20 hours (2 credits) across four years at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), while only 10 hours (1 credit) are allocated to civics. Meanwhile, at the O/L, students will learn 5 compulsory subjects (Mother Tongue, English, Mathematics, Science, and Religion and Value Education), and 2 electives—SNL, history and civics are bunched together with the likes of entrepreneurship here. Unlike the compulsory subjects, which are allocated 140 hours (14 credits or 70 hours each) across two years, those who opt for history or civics as electives would only have 20 hours (2 credits) of learning in each. A further 14 credits per term are for further learning modules, which will allow students to explore their interests before committing to a A/L stream or career path.

With the distribution of credits across a large number of subjects, and the few credits available for SNL, history and civics, social/ethnic cohesion will likely remain on the back burner. It appears to be neglected at primary level, is dealt sparingly at junior secondary level, and relegated to electives in senior years. This means that students will be able to progress through their entire school years, like we did, with very basic competencies in SNL and little understanding of history.

Going forward

Whether the students who experience this curriculum will be able to “resist and respond to hegemonic, divisive forces that pose a threat to social harmony and multicultural coexistence” (p.9) as anticipated in the policy, is questionable. Education policymakers and others must call for more attention to social and ethnic cohesion in the curriculum. However, changes to the curriculum would only be meaningful if accompanied by constitutional reform, abolition of policies, such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (and its proxies), and other political changes.

For now, our school system remains divided by ethnicity and religion. Research from conflict-ridden societies suggests that lack of intercultural exposure in mono-ethnic schools leads to ignorance, prejudice, and polarized positions on politics and national identity. While such problems must be addressed in broader education reform efforts that also safeguard minority identities, the new curriculum revision presents an opportune moment to move this agenda forward.

(Ramya Kumar is attached to the Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

by Ramya Kumar

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoOfficials of NMRA, SPC, and Health Minister under pressure to resign as drug safety concerns mount

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoExpert: Lanka destroying its own food security by depending on imported seeds, chemical-intensive agriculture

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoFlawed drug regulation endangers lives