Features

Shared prosperity: A vision for South Asia

The Lakshman Kadirgamar Memorial Lecture 2023, delivered by Dr. A.K. Abdul Momen, MP

Hon’ble Foreign Minister of Bangladesh

on 03 Feb., 2023.

The event was hosted by the Lakshman Kdirgamar Institute

Of International Relations and Strategic StudiesColombo, Sri Lanka

I am profoundly honoured to have the opportunity to deliver this prestigious Lakshman Kadirgamar Memorial Lecture 2023. I thank the Foreign Minister of Sri Lanka, Mr. Ali Sabry, for this honour.

As an academician, it is my immense pleasure to share my thoughts with the esteemed audience of our close neighbour, Sri Lanka. I am also happy to return to this beautiful island, in less than a year, after the BIMSTEC Summit, held in Colombo.

At the outset, let me pay my homage to late Mr Lakshman Kadirgamar, one of Sri Lanka’s finest sons. He was Foreign Minister during some of the most challenging times in your recent history. Still, he steadily moved towards achieving his dream to build a multi-religious and multi-ethnic united Sri Lanka where all communities could live in harmony. He was a legal scholar and a leader, par excellence. He served to raise the level of the political discourse of Sri Lanka, both at home and abroad. His assassination was one of the most tragic losses for the country. However, we are confident that Lakshman Kadirgamar will be remembered by future generations of Sri Lankans for the values and principles he lived and died for which are even more relevant in present-day Sri Lanka.

I am aware of the regard the late Lakshman Kadirgamar held for Bangladesh. I am also aware that my Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina knew him well. Let me share an anecdote. During one of his visits to Bangladesh, after meeting my Prime Minister, on the way out, she impromptu took him to the stage of her political, public meeting and introduced him to the audience. He even spoke there for a few minutes. Mrs. Kadirgamar who is present here today, was a witness to that episode. That was an indication of how highly the late Kadirgamar was regarded by my Prime Minister. Perhaps all these prompted Mrs Suganthie Kadirgamar to think of hearing from Bangladesh at this year’s Memorial Lecture. I am deeply touched by this gesture. Thank you, Madam.

We see this as an extension of collaboration between LKI and our think tank BIISS.

Today I would like to share my thoughts on the theme “Shared Prosperity: A Vision for South Asia” which we hold very dearly to our heart.

It cannot begin without recalling our Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman who provided our foreign policy dictum “Friendship to all, Malice to None” which he later focused more on promoting relations with neighbours first. His able daughter, Hon’ble Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, aptly picked up the philosophy and extended it and went for its implementation.

Before I delve into the theme, it would be pertinent to put Bangladesh-Sri Lanka bilateral relations in perspective. The relationship is based on multitude of commonalities and close people-to-people contacts. Last year, we celebrated the 50th anniversary of the establishment of our diplomatic ties. We regularly exchange high level visits, are engaged in bilateral discussions on sectoral cooperation, including shipping, trade and commerce, education, agriculture, youth development, connectivity and so on. Our relationship is all about friendship, goodwill and good neighbourliness. Therefore, it is comfortable for me to speak before you in a broader perspective involving the entire region’s development aspect.

Now, why do we think of a holistic approach to prosperity? It is firstly due to the compulsion of the contemporary evolution of global order. We are now going through one of the most significant phases of human history, having already experienced an unprecedented Covid-19 pandemic. Just as we showed our capacity to tame the pandemic, another challenge came in our way – armed conflict in Europe. This has not only slowed down our recovery from the havoc done by the pandemic but also caused a global economic recession due to increase in energy and food prices and, more importantly, disruption of supply chain and financial transaction mechanism, owing to sanctions. Besides, we are also victims of rivalry between big and emerging economies and their strategic power play. All these necessitate the developing countries to get together.

The vision of shared prosperity becomes more relevant when we compare the development trajectory of South Asian countries. Indeed, we have made substantial progress. Some South Asian countries have already graduated to middle income status while others are making their way. Yet, poverty is still high in the region.

One predominant characteristic is that our economies display greater interest in integrating with the global economy than with each other. Regional cooperation, within the existing frameworks, has made only limited progress, being hostage to political and security considerations. The problems have their roots in the historical baggage, as well as the existing disparity in the regional structure. In addition, there are a number of outstanding issues and bilateral discords.

All these realities have left us a message that for survival, we need closer collaboration among neighbours, setting aside our differences; we must have concerted efforts through sharing of experiences and learning from each other.

In this backdrop, Bangladesh has been following a policy of shared prosperity, as a vision for the friendly neighbours of South Asia. Guided by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina, we are advocating for inclusive development in the region. Our development trajectory and ideological stance dovetail our vision of shared prosperity for South Asia. Let me tell how we are doing it.

In Bangladesh, human development is the pillar of sustainable development. Our Father of the Nation, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, in his maiden speech, at the UNGA, in 1974, said, and I quote, “there is an international responsibility … to ensuring everyone the right to a standard living adequate for the health and the well-being of himself and his family”. Unquote.

This vision remains relevant even today. In that spirit, we are pursuing inclusive and people-centric development in association with regional and global efforts.

In the last decade, we have achieved rapid economic growth, ensuring social justice for all. Today, Bangladesh is acknowledged as one of the fastest growing economies in the world. We have reduced poverty from 41.5% to 20% in the last 14 years. Our per capita income has tripled in just a decade. Bangladesh has fulfilled all criterions for graduating from LDC to a developing country. Bangladesh is ranked as world’s 5th best COVID resilient country, and South Asia’s best performer.

Last year, we inaugurated the self-funded ‘Padma Multi-purpose Bridge”. A few days ago, we started the first ever Metro Rail service in our capital. Soon, we shall complete the 3.2 kilometer Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Tunnel under the river Karnaphuli in Chattogram, the first in South Asia. Several other mega-projects are in the pipeline which will bring about significant economic upliftment.

Our aspiration is to transform Bangladesh into a knowledge-based ‘Smart Bangladesh” by 2041 and a prosperous and climate-resilient delta by 2100. We hope to attain these goals by way of ensuring women empowerment, sustainable economic growth and creating opportunities for all.

The priorities of Sheikh Hasina Government are the following:

First, provide food, Second, provide cloths, Third, shelter and accommodation to all and no one should be left behind, Fourth, Education, and Fifth, Healthcare to all. To achieve these goals, she promoted vehicles like Digital Bangladesh, innovation, foreign entrepreneurs and private initiatives in an atmosphere of regional peace, stability and security, and through connectivity. Bangladesh has become a hub of connectivity and looking forward to become a ‘Smart Bangladesh’.

When it comes to foreign policy, we have been pursuing neighbourhood diplomacy for amiable political relations with the South Asian neighbours alongside conducting a balancing act on strategic issues based on the philosophy of “shared prosperity”. I can name a few initiatives which speak of our commitment to the fulfilment of the philosophy.

Bangladesh, within its limited resources, is always ready to stand by her neighbours in times of emergency – be it natural calamity, or pandemic or economic crisis. We despatched essential medicines, medical equipment and technical assistance to the Maldives, Nepal, Bhutan and India during the peak period of the Covid-19 pandemic.

We had readily extended humanitarian assistance to Nepal when they faced the deadly earthquake, back in 2015. Last year, we helped the earthquake victims of Afghanistan. Prior to that, we contributed to the fund raised by the United Nations for the people of Afghanistan.

Further, our assistance for the people of Sri Lanka, with emergency medicines, during the moment of crisis, last year, or the currency SWAP arrangement, is the reflection of our commitment to our philosophy. These symbolic gestures were not about our capacity, pride or mere demonstration, rather it was purely about our sense of obligation to our neighbours. We strongly believe that shared prosperity comes with shared responsibility and development in a single country of a particular region may not sustain if others are not taken along.

In addition, we have resolved most of our critical issues with our neighbours, peacefully, through dialogue and discussion. For example, we have resolved our border demarcation problem with India, our maritime boundary with India and Myanmar, and also our water sharing with India, peacefully, through dialogue and discussion.

For an emerging region, like South Asia, we need to devise certain policies and implement those in a sustainable manner. I would like to share some of my thoughts which could be explored in quest for our shared prosperity and inclusive development:

First of all

, without regional peace and stability we would not be able to grow as aspired for. To that effect, our leaders in the region have to work closely on priority basis. We may have issues between neighbours but we have to transcend that to leave a legacy of harmony for our future generation so that a culture of peace and stability prevails in the region. We can vouch for it from our own experience. In Bangladesh, we are sheltering 1.1 million forcibly displaced Myanmar nationals. If remains unresolved, it has the potential to jeopardise the entire security architecture of South Asia. So, here the neighbourhood should support us for their own interests.

Second

, we need to revitalize our regional platforms and properly implement our initiatives taken under BIMSTEC and IORA. We are happy that BIMSTEC is progressing better, but we should endeavour to make it move always like a rolling machine.

Third

, we need to focus on regional trade and investment. Countries in South Asia had implemented trade liberalization within the framework of SAFTA but in a limited scale. Bangladesh is in the process of concluding Preferential Trade Agreement/Free Trade Agreement with several of its South Asian peers. We have already concluded PTA with Bhutan; are at an advanced stage of negotiations for PTA with Sri Lanka and discussions for PTA with Nepal are on. In the same spirit, Bangladesh is about to start negotiations on Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) with India.

Fourth,

a well-connected region brings immense economic benefits and leads to greater regional integration. To maximize our intra- and extra-regional trade potentials and enhance people-to-people contacts, Bangladesh is committed to regional and sub regional connectivity initiatives. Bangladesh’s geostrategic location is a big leverage which was rightly picked up by our Hon’ble Prime Minister. She benevolently offered connectivity in the form of transit and trans-shipment to our friendly neighbours for sustainable growth and collective prosperity of the region. As for Sri Lanka, if we can establish better shipping connectivity which our two countries are working on, the overall regional connectivity would be more robust.

Fifth

, We live in a globalized world, highly interconnected and interdependent. Our region has gone through similar experience and history. Bangladesh believes and promotes religious harmony. We have been promoting “Culture of Peace” across nations. The basic element of “Culture of Peace” is to inculcate a mindset of tolerance, a mind set of respect towards others, irrespective of religion, ethnicity, colour, background or race. If we can develop such mindset by stopping venom of hatred towards others, we can hope to have sustainable peace and stability across nations, leading to end of violence, wars, and terrorism in nations and regions. There won’t be millions of refugees or persecuted Rohingyas. Bangladesh takes special pride in it as even before Renaissance was started in Europe in the 17th century, even before America was discovered in 1492, in Bengal a campaign was started by Chandi Das as early as 1408 that says “সবার উপরে মানুষ সত্য; তাহার উপরে নাই”- humanity is above all and we still try to promote it.

Sixth

, we have to look beyond a traditional approach of development and challenges and revisit the non-traditional global crises of the recent time. We are experiencing food, fuel, fertiliser and energy shortages due to global politics and disruption of supply chain; as littoral and island countries, we face similar challenges of natural disasters; we have vast maritime area which needs effective maritime governance; we need to curb marine pollution and ensure responsible use of marine resources. Our collective, sincere and bold efforts are required to minimize the impacts of climate change as well.

In this context, I would like to share Bangladesh’s understanding and position.

Ocean Governance:

· Blue Economy:

Bangladesh is an avid proponent of Blue Economy and responsible use of marine resources for the benefit of the entire region. We are keen to utilize the full potential of our marine resources and have developed an integrated maritime policy, drawing on the inter-linkages between the different domains and functions of our seas, oceans and coastal areas. Bangladesh also values the importance of sound science, innovative management, effective enforcement, meaningful partnerships, and robust public participation as essential elements of Blue Economy. At this stage, we need support, technical expertise and investment for sustainable exploration and exploitation of marine resources. As the past and present chairs of IORA, Bangladesh and Sri Lanka should find out ways of bilateral collaboration particularly in Blue Economy in the Bay of Bengal.

· Controlling of Illegal, Unregulated and Unreported (IUU) fishing:

IUU fishing in the maritime territory of Bangladesh needs to be monitored and controlled. Our present capability of marine law enforcement in this regard is limited. Here regional collaboration would be very useful.

· Marine Pollution: Marine pollution is a major concern for all littoral countries. Micro-plastic contamination poses serious threat to marine eco system. Responsible tourism and appropriate legal framework, underpinned by regional collaboration, would greatly help.

Climate Change and Climate Security in the Bay of Bengal:

We have taken a whole-of-government and whole-of-society approach to make the country climate-resilient. Our Climate Change Strategy and Action Plan was formulated in 2009. Bangladesh has pioneered in establishing a climate fund, entirely from our own resources, in 2009. Nearly $443 million has been allocated to this fund since then.

Moreover, we are going to implement the ‘Mujib Climate Prosperity Plan’ to achieve low carbon economic growth for optimised prosperity and partnership. Green growth, resilient infrastructure and renewable energy are key pillars of this prosperity plan. This is a paradigm shift from vulnerability to resilience and now from resilience to prosperity.

As the immediate past Chair of the Climate Vulnerable Forum, we had promoted the interests of the climate vulnerable countries, including Sri Lanka, in the international platforms. Bangladesh is globally acclaimed for its remarkable success in climate adaptation, in particular in locally-led adaptation efforts. The Global Centre on Adaptation (GCA) South Asia regional office in Dhaka is disseminating local based innovative adaptation strategies to other climate vulnerable countries.

To rehabilitate the climate displaced people, we have undertaken one of the world’s largest housing projects which can shelter 4,500 climate displaced families. Under the “Ashrayan” project, a landmark initiative for the landless and homeless people, 450,000 families have been provided with houses. Keeping disaster resilience in mind, the project focuses on mitigation through afforestation, rainwater harvesting, solar home systems and improved cook stoves. In addition, the government has implemented river-bank protection, river excavation and dredging, building of embankment, excavation of irrigation canals and drainage canals in last 10 years at a massive scale. We feel, our national efforts need to be complemented by regional assistance.

As the chair of CVF and as a climate vulnerable country, our priority is to save this planet earth for our future generations. In order to save it, we need all countries, specially those that are major polluters, to come up with aggressive NDCs, so that global temperature remains below 1.5 degree Celsius, they should allocate more funds to climate change, they should share the burden of rehabilitation of ‘climate migrants’ that are uprooted from their sweet homes and traditional jobs due to erratic climatic changes, river erosion and additional salinity. We are happy that “loss and damage” has been introduced in COP-27.

Seventh

, South Asia needs a collective voice in the international forum for optimizing their own interests.

Finally,

and most importantly, South Asian leaders need similar political will for a better and prosperous region.

We hope that Bangladesh and its neighbours in South Asia would be able to tap the potentials of each other’s complementarities to further consolidate our relations to rise and shine as a region. May I conclude by reminding ourselves what a Bengali poet has said, and I quote,

Don’t be afraid of the cloud, sunshine is sure to follow.

With this, I conclude. I thank you all for your graceful presence and patience.

Joy Bangla, Joy Bangabandhu!

Features

Ranking public services with AI — A roadmap to reviving institutions like SriLankan Airlines

Efficacy measures an organisation’s capacity to achieve its mission and intended outcomes under planned or optimal conditions. It differs from efficiency, which focuses on achieving objectives with minimal resources, and effectiveness, which evaluates results in real-world conditions. Today, modern AI tools, using publicly available data, enable objective assessment of the efficacy of Sri Lanka’s government institutions.

Among key public bodies, the Supreme Court of Sri Lanka emerges as the most efficacious, outperforming the Department of Inland Revenue, Sri Lanka Customs, the Election Commission, and Parliament. In the financial and regulatory sector, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) ranks highest, ahead of the Securities and Exchange Commission, the Public Utilities Commission, the Telecommunications Regulatory Commission, the Insurance Regulatory Commission, and the Sri Lanka Standards Institution.

Among state-owned enterprises, the Sri Lanka Ports Authority (SLPA) leads in efficacy, followed by Bank of Ceylon and People’s Bank. Other institutions assessed included the State Pharmaceuticals Corporation, the National Water Supply and Drainage Board, the Ceylon Electricity Board, the Ceylon Petroleum Corporation, and the Sri Lanka Transport Board. At the lower end of the spectrum were Lanka Sathosa and Sri Lankan Airlines, highlighting a critical challenge for the national economy.

Sri Lankan Airlines, consistently ranked at the bottom, has long been a financial drain. Despite successive governments’ reform attempts, sustainable solutions remain elusive.

Globally, the most profitable airlines operate as highly integrated, technology-enabled ecosystems rather than as fragmented departments. Operations, finance, fleet management, route planning, engineering, marketing, and customer service are closely coordinated, sharing real-time data to maximise efficiency, safety, and profitability.

The challenge for Sri Lankan Airlines is structural. Its operations are fragmented, overly hierarchical, and poorly aligned. Simply replacing the CEO or senior leadership will not address these deep-seated weaknesses. What the airline needs is a cohesive, integrated organisational ecosystem that leverages technology for cross-functional planning and real-time decision-making.

The government must urgently consider restructuring Sri Lankan Airlines to encourage:

=Joint planning across operational divisions

=Data-driven, evidence-based decision-making

=Continuous cross-functional consultation

=Collaborative strategic decisions on route rationalisation, fleet renewal, partnerships, and cost management, rather than exclusive top-down mandates

Sustainable reform requires systemic change. Without modernised organisational structures, stronger accountability, and aligned incentives across divisions, financial recovery will remain out of reach. An integrated, performance-oriented model offers the most realistic path to operational efficiency and long-term viability.

Reforming loss-making institutions like Sri Lankan Airlines is not merely a matter of leadership change — it is a structural overhaul essential to ensuring these entities contribute productively to the national economy rather than remain perpetual burdens.

By Chula Goonasekera – Citizen Analyst

Features

Why Pi Day?

International Day of Mathematics falls tomorrow

The approximate value of Pi (π) is 3.14 in mathematics. Therefore, the day 14 March is celebrated as the Pi Day. In 2019, UNESCO proclaimed 14 March as the International Day of Mathematics.

Ancient Babylonians and Egyptians figured out that the circumference of a circle is slightly more than three times its diameter. But they could not come up with an exact value for this ratio although they knew that it is a constant. This constant was later named as π which is a letter in the Greek alphabet.

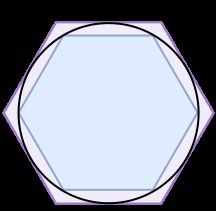

It was the Greek mathematician Archimedes (250 BC) who was able to find an upper bound and a lower bound for this constant. He drew a circle of diameter one unit and drew hexagons inside and outside the circle such that the sides of each hexagon touch the sides of the circle. In mathematics the circle passing through all vertices of a polygon is called a ‘circumcircle’ and the largest circle that fits inside a polygon tangent to all its sides is called an ‘incircle’. The total length of the smaller hexagon then becomes the lower bound of π and the length of the hexagon outside the circle is the upper bound. He realised that by increasing the number of sides of the polygon can make the bounds get closer to the value of Pi and increased the number of sides to 12,24,48 and 60. He argued that by increasing the number of sides will ultimately result in obtaining the original circle, thereby laying the foundation for the theory of limits. He ended up with the lower bound as 22/7 and the upper bound 223/71. He could not continue his research as his hometown Syracuse was invaded by Romans and was killed by one of the soldiers. His last words were ‘do not disturb my circles’, perhaps a reference to his continuing efforts to find the value of π to a greater accuracy.

Archimedes can be considered as the father of geometry. His contributions revolutionised geometry and his methods anticipated integral calculus. He invented the pulley and the hydraulic screw for drawing water from a well. He also discovered the law of hydrostatics. He formulated the law of levers which states that a smaller weight placed farther from a pivot can balance a much heavier weight closer to it. He famously said “Give me a lever long enough and a place to stand and I will move the earth”.

Mathematicians have found many expressions for π as a sum of infinite series that converge to its value. One such famous series is the Leibniz Series found in 1674 by the German mathematician Gottfried Leibniz, which is given below.

π = 4 ( 1 – 1/3 + 1/5 – 1/7 + 1/9 – ………….)

The Indian mathematical genius Ramanujan came up with a magnificent formula in 1910. The short form of the formula is as follows.

π = 9801/(1103 √8)

For practical applications an approximation is sufficient. Even NASA uses only the approximation 3.141592653589793 for its interplanetary navigation calculations.

It is not just an interesting and curious number. It is used for calculations in navigation, encryption, space exploration, video game development and even in medicine. As π is fundamental to spherical geometry, it is at the heart of positioning systems in GPS navigations. It also contributes significantly to cybersecurity. As it is an irrational number it is an excellent foundation for generating randomness required in encryption and securing communications. In the medical field, it helps to calculate blood flow rates and pressure differentials. In diagnostic tools such as CT scans and MRI, pi is an important component in mathematical algorithms and signal processing techniques.

This elegant, never-ending number demonstrates how mathematics transforms into practical applications that shape our world. The possibilities of what it can do are infinite as the number itself. It has become a symbol of beauty and complexity in mathematics. “It matters little who first arrives at an idea, rather what is significant is how far that idea can go.” said Sophie Germain.

Mathematics fans are intrigued by this irrational number and attempt to calculate it as far as they can. In March 2022, Emma Haruka Iwao of Japan calculated it to 100 trillion decimal places in Google Cloud. It had taken 157 days. The Guinness World Record for reciting the number from memory is held by Rajveer Meena of India for 70000 decimal places over 10 hours.

Happy Pi Day!

The author is a senior examiner of the International Baccalaureate in the UK and an educational consultant at the Overseas School of Colombo.

by R N A de Silva

Features

Sheer rise of Realpolitik making the world see the brink

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

As matters stand, there seems to be no credible evidence that the Indian state was aware of the impending torpedoing of the Iranian vessel but these acerbic-tongued politicians of Sri Lanka’s South would have the local public believe that the tragedy was triggered with India’s connivance. Likewise, India is accused of ‘embroiling’ Sri Lanka in the incident on account of seemingly having prior knowledge of it and not warning Sri Lanka about the impending disaster.

It is plain that a process is once again afoot to raise anti-India hysteria in Sri Lanka. An obligation is cast on the Sri Lankan government to ensure that incendiary speculation of the above kind is defeated and India-Sri Lanka relations are prevented from being in any way harmed. Proactive measures are needed by the Sri Lankan government and well meaning quarters to ensure that public discourse in such matters have a factual and rational basis. ‘Knowledge gaps’ could prove hazardous.

Meanwhile, there could be no doubt that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty was violated by the US because the sinking of the Iranian vessel took place in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While there is no international decrying of the incident, and this is to be regretted, Sri Lanka’s helplessness and small player status would enable the US to ‘get away with it’.

Could anything be done by the international community to hold the US to account over the act of lawlessness in question? None is the answer at present. This is because in the current ‘Global Disorder’ major powers could commit the gravest international irregularities with impunity. As the threadbare cliché declares, ‘Might is Right’….. or so it seems.

Unfortunately, the UN could only merely verbally denounce any violations of International Law by the world’s foremost powers. It cannot use countervailing force against violators of the law, for example, on account of the divided nature of the UN Security Council, whose permanent members have shown incapability of seeing eye-to-eye on grave matters relating to International Law and order over the decades.

The foregoing considerations could force the conclusion on uncritical sections that Political Realism or Realpolitik has won out in the end. A basic premise of the school of thought known as Political Realism is that power or force wielded by states and international actors determine the shape, direction and substance of international relations. This school stands in marked contrast to political idealists who essentially proclaim that moral norms and values determine the nature of local and international politics.

While, British political scientist Thomas Hobbes, for instance, was a proponent of Political Realism, political idealism has its roots in the teachings of Socrates, Plato and latterly Friedrich Hegel of Germany, to name just few such notables.

On the face of it, therefore, there is no getting way from the conclusion that coercive force is the deciding factor in international politics. If this were not so, US President Donald Trump in collaboration with Israeli Rightist Premier Benjamin Natanyahu could not have wielded the ‘big stick’, so to speak, on Iran, killed its Supreme Head of State, terrorized the Iranian public and gone ‘scot-free’. That is, currently, the US’ impunity seems to be limitless.

Moreover, the evidence is that the Western bloc is reuniting in the face of Iran’s threats to stymie the flow of oil from West Asia to the rest of the world. The recent G7 summit witnessed a coming together of the foremost powers of the global North to ensure that the West does not suffer grave negative consequences from any future blocking of western oil supplies.

Meanwhile, Israel is having a ‘free run’ of the Middle East, so to speak, picking out perceived adversarial powers, such as Lebanon, and militarily neutralizing them; once again with impunity. On the other hand, Iran has been bringing under assault, with no questions asked, Gulf states that are seen as allying with the US and Israel. West Asia is facing a compounded crisis and International Law seems to be helplessly silent.

Wittingly or unwittingly, matters at the heart of International Law and peace are being obfuscated by some pro-Trump administration commentators meanwhile. For example, retired US Navy Captain Brent Sadler has cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides for the right to self or collective self-defence of UN member states in the face of armed attacks, as justifying the US sinking of the Iranian vessel (See page 2 of The Island of March 10, 2026). But the Article makes it clear that such measures could be resorted to by UN members only ‘ if an armed attack occurs’ against them and under no other circumstances. But no such thing happened in the incident in question and the US acted under a sheer threat perception.

Clearly, the US has violated the Article through its action and has once again demonstrated its tendency to arbitrarily use military might. The general drift of Sadler’s thinking is that in the face of pressing national priorities, obligations of a state under International Law could be side-stepped. This is a sure recipe for international anarchy because in such a policy environment states could pursue their national interests, irrespective of their merits, disregarding in the process their obligations towards the international community.

Moreover, Article 51 repeatedly reiterates the authority of the UN Security Council and the obligation of those states that act in self-defence to report to the Council and be guided by it. Sadler, therefore, could be said to have cited the Article very selectively, whereas, right along member states’ commitments to the UNSC are stressed.

However, it is beyond doubt that international anarchy has strengthened its grip over the world. While the US set destabilizing precedents after the crumbling of the Cold War that paved the way for the current anarchic situation, Russia further aggravated these degenerative trends through its invasion of Ukraine. Stepping back from anarchy has thus emerged as the prime challenge for the world community.

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoWinds of Change:Geopolitics at the crossroads of South and Southeast Asia

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoProf. Dunusinghe warns Lanka at serious risk due to ME war

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoRoyal start favourites in historic Battle of the Blues

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoHeat Index at ‘Caution Level’ in the Sabaragamuwa province and, Colombo, Gampaha, Kurunegala, Anuradhapura, Vavuniya, Hambanthota and Monaragala districts

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe final voyage of the Iranian warship sunk by the US