Features

Seeing the Batticaloa district from the outside during my Ampara days

The people of Batticaloa had learnt to live with a mix of religions and people. On the Christian side were the Jesuit Fathers hard at work training the Tamil boys in English and technology; woodwork being their speciality. The Hindus, with their Kovils and the famous Ramakrishna Ashram at Kallady, were serving the cause of Hindu-based education.

The Ramakrishna Mission on the road out to Kattankudy in Kallady, was a place we visited often. Swamiji Jeevananda was a dynamic character and kept his flock of 200 orphans under a very strict regimen. Yoga exercises, studies, meditation and farming seemed to fill their day. But the boys always appeared alert and eager for more whenever I saw them.

It was a miracle that Swamiji had performed on a sandy bed of land leased out to him by the government many years ago. Compared to the surrounding countryside, the Mission gardens looked like an oasis, full of fruit-bearing trees. Mango and pomegranate trees seemed to bear fruit in all seasons. The care Swamiji bestowed was as much as he gave to his children. Nothing went to waste and everything possible that could nourish the earth went into it.

While taking a walk in the garden with him, if Swamiji saw a fallen leaf, he would, with a deft turn of his big toe, push the leaf into the soil. Leaf compost, he would call it as we walked on.

There were two Buddhist temples one in the heart of Batticaloa city and one near the railway station and they were both well-endowed and looked-after by a group of Sinhalese businessmen, mainly bakers and retailers who had lived in Batticaloa for many years. The peaceful lifestyle was beginning to change during my period there.

Internal seasonal migration for cultivation

One Sunday afternoon, when returning from Colombo, we encountered around Kalkudah a procession of ox carts going west, loaded with people and belongings. My first impression was that some poor village had been visited by a major disaster and the population was fleeing. On inquiring I found that it was the .annual annual migration of the Muslim villagers of Eravur to the banks of the Mahaweli in the Polonnaruwa district, where from time immemorial they had practised tobacco cultivation in the dry season on little leased plots of highland by the side of the river.

The carts were loaded with male children, pots and pans, basins, a bicycle or two, and lots of cadjans, in addition to several sacks of food sufficient to last for weeks. There were no women or girl children in the procession. Each loaded cart with the huge bullock to pull it had another bull or two tethered behind.

I found this fascinating because long ago I had read in Ambassador Philip Crowe’s book Diversions of a Diplomat in Ceylon of the annual migration of the east-coast Muslim farmers to carry out tobacco cultivation along the banks of the Mahaweli river in Tamankaduwa, Polonnaruwa district. Since Damayanthi loved this sort of experience, we decided that we should visit them on the earliest available occasion, and told the travellers so.

The next Sunday we drove up by jeep past the Manampitiya bridge and turning right, got within the next hour to their tobacco farms. We were given a royal welcome and treated to a marvelous spread of jungle fowl and manioc. The cultivation was in fun swing and the method of irrigation was one I had never seen before in Sri Lanka. On a visit to Egypt with Dudley Senanayake in 1967, I had heard of this ancient method of irrigation being practised on the banks of the Nile.

The land the farmers used for their tobacco cultivation was about 10-15 feet above the level of the river. The water had to be lifted up for the crop to be irrigated. What the farmers were doing was to use their bullocks as walking machines to hoist the water up to the top in large leather buckets made of cattle-hide loosely stitched together. The leather bucket was attached to a rope and a pulley was fixed to a pole which jutted out over the water with the end of the rope around the bullock’s neck. When the bullock walked back, and they had learned to walk backwards about 10 paces, the bucket would come up full. When the bullock came forward, the bucket went down. It was an extraordinarily simple, ingenious age-old device of lift irrigation.

Social action by the missionaries

The Jesuit Fathers were very prominent in the work they were doing in education. In addition to the schools they were connected with, they had moved into vocational training and had developed modern techniques, especially in carpentry. Some of the young Jesuit Brothers themselves were experts in handling the new technology and passing it on to the youngsters they were training. The older ones like Fr Weber were focusing on sports especially the development of basketball.

At this time St Michael’s College, Batticaloa was perhaps the leading school in the sport of basketball. They won most of the national championships. Fr Weber’s contribution to Batticaloa was recognized by naming the large playing field in the centre of the town as the Weber Stadium. Out in the field, the training in managing accounts given by the diminutive Sister Gabriel of the Franciscan Order to the fishermen of Mankerni was inspiring.

Illegal settlements in Vakaneri

Around the middle of 1972,1 began to get reports of encroachments of people from outside the district on crown land above the Vakaneri tank. On inquiry I found that about 300 families from the upcountry Tamils of Indian origin, who had found it difficult to obtain employment on plantations on the estates had begun coming into Batticaloa and settling down with the assistance of local officials. I heard that K W Devanayagam (Bill), whom I knew very well and who was an MP of Kalkudah, had sanctioned these settlements.

I immediately called up Bill and told him that this was wrong and illegal and that I would have no alternative but to take action to evict the encroachers. Bill pleaded with me to give them time as they were destitute people and had no other place to go to in the country. I told him I would need to have this taken up by Colombo and immediately informed the Land Commissioner and other relevant authorities about it.

On inspecting the lands, I found that the encroachers were extremely poor and were literally putting up their huts with their bare hands. I had to regretfully tell them that they would have to move since the state land was needed for other purposes. Bill tried his best to plead their cause but on orders coming down from Colombo, I had no alternative but to initiate their eviction from that particular block of land. Where they went after that I did not know. Bill was clearly upset at my order but as I had worked with him when I was secretary to Dudley Senanayake and he was a parliamentary secretary in that Cabinet, I think he understood that duty was duty. He later went on to become chairman of the Public Service Commission.

The riddle of the shifting district boundary

The district adjoining mine was Polonnaruwa and I had some interesting experiences with the high priest of the Dimbulagala Monastery. The priest was a legend in the area and when I first met him he told me a story of how he had been saved from an attempted assassination because of the charms he had used. Apparently a vanload of robbers had come up the mountain into his cell and tried to shoot at him, but the bullets had missed. He was a very outspoken person and boasted of an occasion on which he had actually hit a minister of irrigation with his umbrella because the minister had not agreed to his request for water to the fields in the area.

The question of the exact point of the boundary between the two districts of Batticaloa and Polonnaruwa on the main road began to attract our attention. There was a big signboard on the road which I noticed was beginning to change position regularly. The engineers on the Polonnaruwa side would put it up at a particular point but a few days later, the board would be brought down and erected at another point, a mile or two closer to Batticaloa. It was rumoured that the hand behind this was that of my good friend, the high priest of Dimbulagala. When I asked him about this he jocularly remarked that things like that happen in the area because it was a crossing point for elephants. His theory was that the board had been transported from point to point by a particularly playful herd of elephants!

Esala’s education

Although Batticaloa was extremely pleasant with its collection of highly civilized people to deal with at a social and political level, the fact that my son had two years of his education in the Sinhala stream at St Michael’s College was beginning to cause some concern. The class had about 12 students ranging from the resthouse keeper’s son to the son of a farmer in a Gal Oya colony. Our son enjoyed himself immensely extending his friendships with the children of these working people. However, the teaching was not up to the mark Sinhala teachers being very reluctant to serve in Batticaloa or anywhere in the east. So we soon had to begin once more to look for a better school for him.

I begin to look for a job abroad

It was now coming on to three years in the districts. I was 43 and it seemed a good time to be looking out for a job abroad. I had missed one chance to work for the World Bank in Bangladesh and it looked as if another opportunity would not come if I didn’t exert myself.

So, when I saw that the post of regional director in IPPF in the Indian Ocean region was falling vacant and South-Asians were invited to apply, I thought I would put in my bid. Thinking that having worked for a former prime minister would be an added qualification in a somewhat political job, I asked Dudley whether he would be kind enough to give me a letter of commendation. He said he would. Menikdiwela, who became secretary to the leader of the opposition and remained close to Dudley, told me later that Dudley had sent to the IPPF a tribute to my work with his commendation.

Dudley Senanayake’s letter to Bradman

He wrote me this letter (see p 190) saying that he would help. However, the letter carried some regret that I intended leaving the service of the government. It wasn’t a government of which he was a party but he still cared. My bid, however, failed I didn’t know whether it was due to Dudley’s recommendation and I informed him that I had not been able to get the job. He then wrote me a wonderful letter which I thought made up fully for the loss of the job.

The stirring of ethnic tension

Unlike in the north, where the ethnic question was leading to the rise of militancy and an aggressive attitude to government and Sinhalese people, the situation was different in the east. It was more accommodative and in line with the almost philosophical attitude of the Batticaloa people to live and let live. There were possibly good functional reasons for this. The mix of communities did not allow for any especially dominant group-consciousness to emerge, the three communities the Tamil, the Muslim and the Sinhalese being more or less in equal numbers. Another could have been the long – history of contact and commerce with the Sinhala majority areas and the availability of long-established transport links.

At least four roads linked this area with the Central Province and Uva westwards from Kalkudah by the Manampitiya road; Southeastwards from Chenkaladi by the Maha Oya road; further south by the Ampara-Uhana-Mahiyangana road and to the southwest from Pottuvil by the Moneragala road. This was different from the situation in the north where other than the A9 running through the buffer zone of the Vanni there was virtually no connection with the Sinhalese-speaking provinces.

Sirimavo’s policy of language standardization for university entrants, though not as drastic in its application in Batticaloa as to those seeking entrance in Jaffna, was yet reason enough for agitation. The feeling against the Sinhalese policemen, migrant fishermen, government officials and traders was rising and transcending what had always been the more structural divide between the Tamil northerners and easterners. This was quite apparent among the kachcheri staff themselves and I sometimes had to hold the balance between the cliques which had formed on this basis.

The 1972/73 language media-wise standardisation for admission to the universities had resulted in the following transformation:

Year Faculty Sinhalese Tamil

1969 Engineering 51.7 48.3

Medical 50.0 50.0

1975 Engineering 83.4 16.6

Medical 81.0 19.0

(Figures show percentage-wise change)

The other issue which evoked much critical comment at the officials club and other fora in those days were the changes effected by the new Republican Constitution of 1972. The concern was about the removal of Section 29 2 (c) which the Tamils felt had been included in the Soulbury Constitution under which the country had been governed so far, to provide protection against legislation which could discriminate against their interests as a community.

A time to move on

We loved Batticaloa and the two years there passed by very pleasantly. Our bungalow was situated on the bank of the lagoon and having breakfast on the upper floor watching the sailing boats drift by was extremely soothing. Once we were surprised by a large schooner in full sail which had possibly come in from India and was searching for deeper anchorage near Buffalo Island just a few hundred yards in front of us.

The Sinhalese traders in the town wanted to organize a ceremonial farewell when we left on transfer to Galle in the middle of 1974. I protested and wanted nothing of it but could do little to prevent Ananda of the Lanka Bakery, who was quite active on behalf of the small minority of Sinhalese, to take us on a sort of ‘victory motorcade’, replete with school children waving little Lion flags and the crackle of the traditional `cheena pattas’ as we made our way to the Batticaloa railway station. It was a moment mixed with embarrassment for our Tamil friends who had treated us with such warmth and generosity and gratitude for the Sinhalese who had at a time of oncoming uncertainty responded in the only way they knew to say ‘thanks for holding the scales evenly’.

(Excerpted from Rendering Unto Caesar by Bradman Weerakoon)

Features

Australia’s social media ban: A sledgehammer approach to a scalpel problem

When governments panic, they legislate. When they legislate in panic, they create monsters. Australia’s world-first ban on social media for under-16s, which came into force on 10 December, 2025, is precisely such a monster, a clumsy, authoritarian response to a legitimate problem that threatens to do more harm than good.

When governments panic, they legislate. When they legislate in panic, they create monsters. Australia’s world-first ban on social media for under-16s, which came into force on 10 December, 2025, is precisely such a monster, a clumsy, authoritarian response to a legitimate problem that threatens to do more harm than good.

Prime Minister Anthony Albanese hailed it as a “proud day” for Australian families. One wonders what there is to be proud about when a liberal democracy resorts to blanket censorship, violates children’s fundamental rights, and outsources enforcement to the very tech giants it claims to be taming. This is not protection; it is political theatre masquerading as policy.

The Seduction of Simplicity

The ban’s appeal is obvious. Social media platforms have become toxic playgrounds where children are subjected to cyberbullying, addictive algorithms, and content that can genuinely harm their mental health. The statistics are damning: 40% of Australian teens have experienced cyberbullying, youth self-harm hospital admissions rose 47% between 2012 and 2022, and depression rates have skyrocketed in tandem with smartphone adoption. These are real problems demanding real solutions.

But here’s where Australia has gone catastrophically wrong: it has conflated correlation with causation and chosen punishment over education, restriction over reform, and authoritarian control over empowerment. The ban assumes that removing children from social media will magically solve mental health crises, as if these platforms emerged in a vacuum rather than as symptoms of deeper societal failures, inadequate mental health services, overworked parents, underfunded schools, and a culture that has outsourced child-rearing to screens.

Dr. Naomi Lott of the University of Reading hit the nail on the head when she argued that the ban unfairly burdens youth for tech firms’ failures in content moderation and algorithm design. Why should children pay the price for corporate malfeasance? This is akin to banning teenagers from roads because car manufacturers built unsafe vehicles, rather than holding those manufacturers accountable.

The Enforcement Farce

The practical implementation of this ban reads like dystopian satire. Platforms must take “reasonable steps” to prevent access, a phrase so vague it could mean anything or nothing. The age verification methods being deployed include AI-driven facial recognition, behavioural analysis, government ID scans, and something called “AgeKeys.” Each comes with its own Pandora’s box of problems.

Facial recognition technology has well-documented biases against ethnic minorities. Behavioural analysis can be easily gamed by tech-savvy teenagers. ID scans create massive privacy risks in a country that has suffered repeated data breaches. And zero-knowledge proof, while theoretically elegant, require a level of technical sophistication that makes them impractical for mass adoption.

Already, teenagers are bragging online about circumventing the restrictions, prompting Albanese’s impotent rebuke. What did he expect? That Australian youth would simply accept digital exile? The history of prohibition, from alcohol to file-sharing, teaches us that determined users will always find workarounds. The ban doesn’t eliminate risk; it merely drives it underground where it becomes harder to monitor and address.

Even more absurdly, platforms like YouTube have expressed doubts about enforcement, and Opposition Leader Sussan Ley has declared she has “no confidence” in the ban’s efficacy. When your own political opposition and the companies tasked with implementing your policy both say it won’t work, perhaps that’s a sign you should reconsider.

The Rights We’re Trading Away

The legal challenges now percolating through Australia’s High Court get to the heart of what’s really at stake here. The Digital Freedom Project, led by teenagers Noah Jones and Macy Neyland, argues that the ban violates the implied constitutional freedom of political communication. They’re right. Social media platforms, for all their flaws, have become essential venues for democratic discourse. By age 16, many young Australians are politically aware, engaged in climate activism, and participating in public debates. This ban silences them.

The government’s response, that child welfare trumps absolute freedom, sounds reasonable until you examine it closely. Child welfare is being invoked as a rhetorical trump card to justify what is essentially state paternalism. The government isn’t protecting children from objective harm; it’s making a value judgment about what information they should be allowed to access and what communities they should be permitted to join. That’s thought control, not child protection.

Moreover, the ban creates a two-tiered system of rights. Those over 16 can access platforms; those under cannot, regardless of maturity, need, or circumstance. A 15-year-old seeking LGBTQ+ support groups, mental health resources, or information about escaping domestic abuse is now cut off from potentially life-saving communities. A 15-year-old living in rural Australia, isolated from peers, loses a vital social lifeline. The ban is blunt force trauma applied to a problem requiring surgical precision.

The Privacy Nightmare

Let’s talk about the elephant in the digital room: data security. Australia’s track record here is abysmal. The country has experienced multiple high-profile data breaches, and now it’s mandating that platforms collect biometric data, government IDs, and behavioural information from millions of users, including adults who will need to verify their age to distinguish themselves from banned minors.

The legislation claims to mandate “data minimisation” and promises that information collected solely for age verification will be destroyed post-verification. These promises are worth less than the pixels they’re displayed on. Once data is collected, it exists. It can be hacked. It can be subpoenaed. It can be repurposed. The fine for violations, up to AUD 9.5 million, sounds impressive until you realise that’s pocket change for tech giants making billions annually.

We’re creating a massive honeypot of sensitive information about children and families, and we’re trusting companies with questionable data stewardship records to protect it. What could possibly go wrong?

The Global Domino Delusion

Proponents like US Senator Josh Hawley and author Jonathan Haidt praise Australia’s ban as a “bold precedent” that will trigger global reform. This is wishful thinking bordering on delusion. What Australia has actually created is a case study in how not to regulate technology.

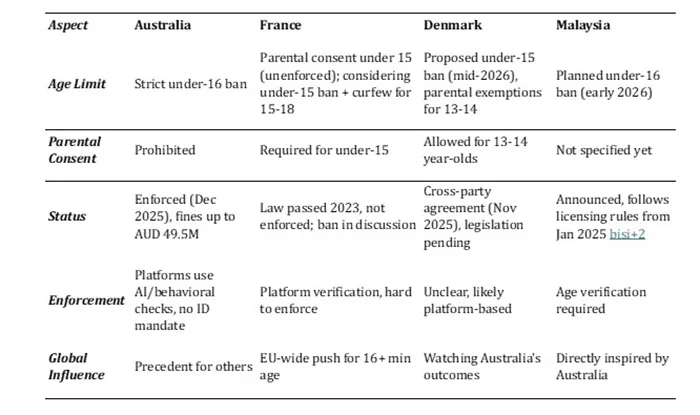

France, Denmark, and Malaysia are watching, but with notable differences. France’s model includes parental consent options. Denmark proposes exemptions for 13-14-year-olds with parental approval. These approaches recognise what Australia refuses to acknowledge: that blanket prohibitions fail to account for individual circumstances and family autonomy.

The comparison table in the document reveals the stark rigidity of Australia’s approach. It’s the only country attempting outright prohibition without parental consent. This isn’t leadership; it’s extremism. Other nations may cherry-pick elements of Australia’s approach while avoiding its most draconian features. (See Table)

The Real Solutions We’re Ignoring

Here’s what actual child protection would look like: holding platforms legally accountable for algorithmic harm, mandating transparent content moderation, requiring platforms to offer chronological feeds instead of engagement-maximising algorithms, funding digital literacy programmes in schools, properly resourcing mental health services for young people, and empowering parents with better tools to guide their children’s online experiences.

Instead, Australia has chosen the path of least intellectual effort: ban it and hope for the best. This is governance by bumper sticker, policy by panic.

Mia Bannister, whose son’s suicide has been invoked repeatedly to justify the ban, called parental enforcement “short-term pain, long-term gain” and urged families to remove devices entirely. But her tragedy, however heart-wrenching, doesn’t justify bad policy. Individual cases, no matter how emotionally compelling, are poor foundations for sweeping legislation affecting millions.

Conclusion: The Tyranny of Good Intentions

Australia’s social media ban is built on good intentions, genuine concerns about child welfare, and understandable frustration with unaccountable tech giants. But good intentions pave a very particular road, and this road leads to a place where governments dictate what information citizens can access based on age, where privacy becomes a quaint relic, and where young people are infantilised rather than educated.

The ban will fail on its own terms, teenagers will circumvent it, platforms will struggle with enforcement, and the mental health crisis will continue because it was never primarily about social media. But it will succeed in normalising digital authoritarianism, expanding surveillance infrastructure, and teaching young Australians that their rights are negotiable commodities.

When this ban inevitably fails, when the promised mental health improvements don’t materialize, when data breaches expose the verification systems, and when teenagers continue to access prohibited platforms through VPNs and workarounds, Australia will face a choice: double down on enforcement, creating an even more invasive surveillance state, or admit that the entire exercise was a costly mistake.

Smart money says they’ll choose the former. After all, once governments acquire new powers, they rarely relinquish them willingly. And that’s the real danger here, not that Australia will fail to protect children from social media, but that it will succeed in building the infrastructure for a far more intrusive state. The platforms may be the proximate target, but the ultimate casualties will be freedom, privacy, and trust.

Australia didn’t need a world-first ban. It needed world-class thinking. Instead, it settled for a world of trouble.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Sustaining good governance requires good systems

A prominent feature of the first year of the NPP government is that it has not engaged in the institutional reforms which was expected of it. This observation comes in the context of the extraordinary mandate with which the government was elected and the high expectations that accompanied its rise to power. When in opposition and in its election manifesto, the JVP and NPP took a prominent role in advocating good governance systems for the country. They insisted on constitutional reform that included the abolition of the executive presidency and the concentration of power it epitomises, the strengthening of independent institutions that overlook key state institutions such as the judiciary, public service and police, and the reform or repeal of repressive laws such as the PTA and the Online Safety Act.

The transformation of a political party that averaged between three to five percent of the popular vote into one that currently forms the government with a two thirds majority in parliament is a testament to the faith that the general population placed in the JVP/ NPP combine. This faith was the outcome of more than three decades of disciplined conduct in the aftermath of the bitter experience of the 1988 to 1990 period of JVP insurrection. The manner in which the handful of JVP parliamentarians engaged in debate with well researched critiques of government policy and actions, and their service in times of disaster such as the tsunami of 2004 won them the trust of the people. This faith was bolstered by the Aragalaya movement which galvanized the citizens against the ruling elites of the past.

In this context, the long delay to repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act which has earned notoriety for its abuse especially against ethnic and religious minorities, has been a disappointment to those who value human rights. So has been the delay in appointing an Auditor General, so important in ensuring accountability for the money expended by the state. The PTA has a long history of being used without restraint against those deemed to be anti-state which, ironically enough, included the JVP in the period 1988 to 1990. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), published in December 2025, is the latest attempt to repeal and replace the PTA. Unfortunately, the PSTA largely replicates the structure, logic and dangers of previous failed counter terrorism bills, including the Counter Terrorism Act of 2018 and the Anti Terrorism Act proposed in 2023.

Misguided Assumption

Despite its stated commitment to rule of law and fundamental rights, the draft PTSA reproduces many of the core defects of the PTA. In a preliminary statement, the Centre for Policy Alternatives has observed among other things that “if there is a Detention Order made against the person, then in combination, the period of remand and detention can extend up to two years. This means that a person can languish in detention for up to two years without being charged with a crime. Such a long period again raises questions of the power of the State to target individuals, exacerbated by Sri Lanka’s history of long periods of remand and detention, which has contributed to abuse and violence.” Human Rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal has warned against the broad definition of terrorism under the proposed law: “The definition empowers state officials to term acts of dissent and civil disobedience as ‘terrorism’ and will lawfully permit disproportionate and excessive responses.” The legitimate and peaceful protests against abuse of power by the authorities cannot be classified as acts of terror.

The willingness to retain such powers reflects the surmise that the government feels that keeping in place the structures that come from the past is to their benefit, as they can utilise those powers in a crisis. Due to the strict discipline that exists within the JVP/NPP at this time there may be an assumption that those the party appoints will not abuse their trust. However, the country’s experience with draconian laws designed for exceptional circumstances demonstrates that they tend to become tools of routine governance. On the plus side, the government has given two months for public comment which will become meaningful if the inputs from civil society actors are taken into consideration.

Worldwide experience has repeatedly demonstrated that integrity at the level of individual leaders, while necessary, is not sufficient to guarantee good governance over time. This is where the absence of institutional reform becomes significant. The aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah in particular has necessitated massive procurements of emergency relief which have to be disbursed at maximum speed. There are also significant amounts of foreign aid flowing into the country to help it deal with the relief and recovery phase. There are protocols in place that need to be followed and monitored so that a fiasco like the disappearance of tsunami aid in 2004 does not recur. To the government’s credit there are no such allegations at the present time. But precautions need to be in place, and those precautions depend less on trust in individuals than on the strength and independence of oversight institutions.

Inappropriate Appointments

It is in this context that the government’s efforts to appoint its own preferred nominees to the Auditor General’s Department has also come as a disappointment to civil society groups. The unsuitability of the latest presidential nominee has given rise to the surmise that this nomination was a time buying exercise to make an acting appointment. For the fourth time, the Constitutional Council refused to accept the president’s nominee. The term of the three independent civil society members of the Constitutional Council ends in January which would give the government the opportunity to appoint three new members of its choice and get its way in the future.

The failure to appoint a permanent Auditor General has created an institutional vacuum at a critical moment. The Auditor General acts as a watchdog, ensuring effective service delivery promoting integrity in public administration and providing an independent review of the performance and accountability. Transparency International has observed “The sequence of events following the retirement of the previous Auditor General points to a broader political inertia and a governance failure. Despite the clear constitutional importance of the role, the appointment process has remained protracted and opaque, raising serious questions about political will and commitment to accountability.”

It would appear that the government leadership takes the position they have been given the mandate to govern the country which requires implementation by those they have confidence in. This may explain their approach to the appointment (or non-appointment) at this time of the Auditor General. Yet this approach carries risks. Institutions are designed to function beyond the lifespan of any one government and to protect the public interest even when those in power are tempted to act otherwise. The challenge and opportunity for the NPP government is to safeguard independent institutions and enact just laws, so that the promise of system change endures beyond personalities and political cycles.

by Jehan Perera

Features

General education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

General education reform presents an opportunity to explore ways to promote social and ethnic cohesion. A school curriculum could foster shared values, empathy, and critical thinking, through social studies and civics education, implement inclusive language policies, and raise critical awareness about our collective histories. Yet, the government’s new policy document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025, leaves us little to look forward to in this regard.

The policy document points to several “salient” features within it, including: 1) a school credit system to quantify learning; 2) module-based formative and summative assessments to replace end-of-term tests; 3) skills assessment in Grade 9 consisting of a ‘literacy and numeracy test’ and a ‘career interest test’; 4) a comprehensive GPA-based reporting system spanning the various phases of education; 5) blended learning that combines online with classroom teaching; 6) learning units to guide students to select their preferred career pathways; 7) technology modules; 8) innovation labs; and 9) Early Childhood Education (ECE). Notably, social and ethnic cohesion does not appear in this list. Here, I explore how the proposed curriculum reforms align (or do not align) with the NPP’s pledge to inculcate “[s]afety, mutual understanding, trust and rights of all ethnicities and religious groups” (p.127), in their 2024 Election Manifesto.

Language/ethnicity in the present curriculum

The civil war ended over 15 years ago, but our general education system has done little to bring ethnic communities together. In fact, most students still cannot speak in the “second national language” (SNL) and textbooks continue to reinforce negative stereotyping of ethnic minorities, while leaving out crucial elements of our post-independence history.

Although SNL has been a compulsory subject since the 1990s, the hours dedicated to SNL are few, curricula poorly developed, and trained teachers few (Perera, 2025). Perhaps due to unconscious bias and for ideological reasons, SNL is not valued by parents and school communities more broadly. Most students, who enter our Faculty, only have basic reading/writing skills in SNL, apart from the few Muslim and Tamil students who schooled outside the North and the East; they pick up SNL by virtue of their environment, not the school curriculum.

Regardless of ethnic background, most undergraduates seem to be ignorant about crucial aspects of our country’s history of ethnic conflict. The Grade 11 history textbook, which contains the only chapter on the post-independence period, does not mention the civil war or the events that led up to it. While the textbook valourises ‘Sinhala Only’ as an anti-colonial policy (p.11), the material covering the period thereafter fails to mention the anti-Tamil riots, rise of rebel groups, escalation of civil war, and JVP insurrections. The words “Tamil” and “Muslim” appear most frequently in the chapter, ‘National Renaissance,’ which cursorily mentions “Sinhalese-Muslim riots” vis-à-vis the Temperance Movement (p.57). The disenfranchisement of the Malaiyaha Tamils and their history are completely left out.

Given the horrifying experiences of war and exclusion experienced by many of our peoples since independence, and because most students still learn in mono-ethnic schools having little interaction with the ‘Other’, it is not surprising that our undergraduates find it difficult to mix across language and ethnic communities. This environment also creates fertile ground for polarizing discourses that further divide and segregate students once they enter university.

More of the same?

How does Transforming General Education seek to address these problems? The introduction begins on a positive note: “The proposed reforms will create citizens with a critical consciousness who will respect and appreciate the diversity they see around them, along the lines of ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, and other areas of difference” (p.1). Although National Education Goal no. 8 somewhat problematically aims to “Develop a patriotic Sri Lankan citizen fostering national cohesion, national integrity, and national unity while respecting cultural diversity (p. 2), the curriculum reforms aim to embed values of “equity, inclusivity, and social justice” (p. 9) through education. Such buzzwords appear through the introduction, but are not reflected in the reforms.

Learning SNL is promoted under Language and Literacy (Learning Area no. 1) as “a critical means of reconciliation and co-existence”, but the number of hours assigned to SNL are minimal. For instance, at primary level (Grades 1 to 5), only 0.3 to 1 hour is allocated to SNL per week. Meanwhile, at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), out of 35 credits (30 credits across 15 essential subjects that include SNL, history and civics; 3 credits of further learning modules; and 2 credits of transversal skills modules (p. 13, pp.18-19), SNL receives 1 credit (10 hours) per term. Like other essential subjects, SNL is to be assessed through formative and summative assessments within modules. As details of the Grade 9 skills assessment are not provided in the document, it is unclear whether SNL assessments will be included in the ‘Literacy and numeracy test’. At senior secondary level – phase 1 (Grades 10-11 – O/L equivalent), SNL is listed as an elective.

Refreshingly, the policy document does acknowledge the detrimental effects of funding cuts in the humanities and social sciences, and highlights their importance for creating knowledge that could help to “eradicate socioeconomic divisions and inequalities” (p.5-6). It goes on to point to the salience of the Humanities and Social Sciences Education under Learning Area no. 6 (p.12):

“Humanities and Social Sciences education is vital for students to develop as well as critique various forms of identities so that they have an awareness of their role in their immediate communities and nation. Such awareness will allow them to contribute towards the strengthening of democracy and intercommunal dialogue, which is necessary for peace and reconciliation. Furthermore, a strong grounding in the Humanities and Social Sciences will lead to equity and social justice concerning caste, disability, gender, and other features of social stratification.”

Sadly, the seemingly progressive philosophy guiding has not moulded the new curriculum. Subjects that could potentially address social/ethnic cohesion, such as environmental studies, history and civics, are not listed as learning areas at the primary level. History is allocated 20 hours (2 credits) across four years at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), while only 10 hours (1 credit) are allocated to civics. Meanwhile, at the O/L, students will learn 5 compulsory subjects (Mother Tongue, English, Mathematics, Science, and Religion and Value Education), and 2 electives—SNL, history and civics are bunched together with the likes of entrepreneurship here. Unlike the compulsory subjects, which are allocated 140 hours (14 credits or 70 hours each) across two years, those who opt for history or civics as electives would only have 20 hours (2 credits) of learning in each. A further 14 credits per term are for further learning modules, which will allow students to explore their interests before committing to a A/L stream or career path.

With the distribution of credits across a large number of subjects, and the few credits available for SNL, history and civics, social/ethnic cohesion will likely remain on the back burner. It appears to be neglected at primary level, is dealt sparingly at junior secondary level, and relegated to electives in senior years. This means that students will be able to progress through their entire school years, like we did, with very basic competencies in SNL and little understanding of history.

Going forward

Whether the students who experience this curriculum will be able to “resist and respond to hegemonic, divisive forces that pose a threat to social harmony and multicultural coexistence” (p.9) as anticipated in the policy, is questionable. Education policymakers and others must call for more attention to social and ethnic cohesion in the curriculum. However, changes to the curriculum would only be meaningful if accompanied by constitutional reform, abolition of policies, such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (and its proxies), and other political changes.

For now, our school system remains divided by ethnicity and religion. Research from conflict-ridden societies suggests that lack of intercultural exposure in mono-ethnic schools leads to ignorance, prejudice, and polarized positions on politics and national identity. While such problems must be addressed in broader education reform efforts that also safeguard minority identities, the new curriculum revision presents an opportune moment to move this agenda forward.

(Ramya Kumar is attached to the Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

by Ramya Kumar

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoOfficials of NMRA, SPC, and Health Minister under pressure to resign as drug safety concerns mount

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoFlawed drug regulation endangers lives

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoExpert: Lanka destroying its own food security by depending on imported seeds, chemical-intensive agriculture