Opinion

Repeal of Online Safety Act vital for economic salvation of Sri Lanka

I. Imminent Danger

While the economy of Sri Lanka has achieved some degree of stabilisation after the most dire crisis in history, progress along a growth trajectory remains a clear imperative. Fragility of the current situation has been massively increased by the devastating tariffs imposed by the Trump Administration, making our country’s exports to the United States – especially apparel and rubber products – starkly vulnerable.

Against this backdrop the GSP+ facility, affording preferential access to the vast markets of the European Union, becomes a lifeline for our exports. Exemption from import duty for a wide array of products involves an advantage of immense value.

This is, however,neither a right nor an entitlement, and its availability is by no means assured in perpetuity. Its continued enjoyment is conditional upon compliance with provisions contained in 27 treaties, principally the International Convention on Civil and Political Rights. Aspects of this have been incorporated into the domestic legal system of Sri Lanka, by legislation in the drafting of which,as Minister of Export Development and International Trade, I played a key role in 2007.

GSP+ privileges for Sri Lanka are now coming up for review, with a delegation from Brussels expected to arrive very shortly.

One of Sri Lanka’s abiding commitments is a fundamental modification of the Online Safety Act, No. 9 of 2024, an unforgiving onslaught on media freedom, which was vehemently opposed by political parties across the spectrum, and representatives of the media and civil society. Despite the outrageous contents of the Act, no action whatever has been taken up to now, to amend this legislation. There is no doubt that this situation, if it is allowed to continue, will gravely impede vital interests in respect of our international trade. Certainly, the government’s professed intention of enhancing the value of exports to the European Union to the threshold of 3.6 billion dollars in the short term, will be reduced to a fanciful expectation.It is, therefore, a matter of urgent practical importance to identify the most obnoxious features of the law and to set in motion the legislative procedures necessary to effect their repeal or radical reform.

II. Overbroad Definition of Offences

A defect going to the very root of the legislation is a definition which is strikingly vague and overbroad: “Any person, whether in or outside Sri Lanka, who poses a threat to national security, public health or public order or promotes feelings of ill-will and hostility between different classes of people, by communicating a false statement, commits an offence” (Section 12).

The central criterion itself is an attack on basic democratic values. There has been judicial recognition of the reality that “Erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate” (New York Times vs. Sullivan 376 U.S. 254 at p. 270 – 1 (1964). The solution, in a democratic culture, is not suppression but refutation of falsehood through enhanced engagement and challenge.

The central objection is to the use of subjective language like “ill-will” and “hostility” as elements of the definition of a penal offence carrying condign penalties, including long periods of rigorous imprisonment. Inherent vagueness leads to unpredictability of consequences.

Equally compelling considerations apply to the use of “national security” as a lever for restraint on expression and publication. Public policy, as set out in the Johannesburg Principles on National Security, Freedom of Expression and Access to Information (Preamble to UN Document E/CN 4/1996/39), adopted on 1 October 1995, emphasises the need “to discourage governments from using the pretext of national security to place unjustified restrictions on the exercise of freedom of speech and expression”.

It is the absence of necessary qualification that violates the basic ethos of a democratic society.A “threat” to national security, public health or public order as the basis of restriction on free speech and communication is unacceptable without essential limitation.The internationally accepted test of “clear and present danger”(Schenk vs. U.S. 249 U.S. 247 at p.52 (1919)) is in no way reflected as a qualifying element in the Sri Lankan legislation.

III. Overarching Authority of the Commission

The crux of the pivotal offence is a “false statement”. The truth or falsity of the statement complained of, is a matter to be determined at the untrammelled discretion of the Online Safety Commission, the central authority created by the law. It is composed of 5 members appointed by the President,with the concurrence of the Constitutional Council.

A vital circumstance is that members of the Online Safety Commission, unlike the membership of other independent Commissions established under the Constitution, are not recommended for appointment by the Constitutional Council. The initiative is that of the President, not the Constitutional Council, the function of the latter being confined to “approval” (Section 5 (1)). This is a marked, and in principle unacceptable, departure from the pattern of constitutional provisions governing the appointment of independent Commissions.

This difference of approach undeniably impacts public perceptions regarding performance of the Commission’s functions in a spirit of total independence – a result much to be regretted, in view of the awesome sweep of powers conferred on the Commission. These include the prohibition, by mere fiat of the Commission,of statements pertaining to a diversity of matters such as physical security,ethnic and religious harmony,disaffection to the State, personal wellbeing and privacy, and interference with the right of association.

In any event, given the invasion of seminal rights and freedoms as the direct consequence of exercise of the Commission’s powers, it is reasonable to assume the desirability of a process of consultation which would include, among others, internet service providers, internet intermediaries, and representatives of media organisations, as well as the professional, business and academic communities.

Incompatibility of scope and objectives of this Act with the irreducible norms of a functioning democracy is clear from judicial pronouncements of impeccable authority: “The freedom of speech and expression is one which cannot be denied without violating those principles of liberty and justice which lie at the base of all civil and political institutions” (Mark Fernando J. in Amaratunga v. Sirimal, The Jana Ghose Case, S.C. Application No. 468/92).

The reality of this danger is reinforced by implications of the definition of a “false statement”, the anchor of criminal liability in terms of the Act: “A ‘false statement’ means a statement that is known or believed by the maker to be incorrect or untrue and is made especially with the intent to deceive or mislead but does not include a caution, an opinion or imputation made in good faith” (section 52). The manner of formulation suggests that the concluding phrase is in the nature of an exception from criminal liability, the burden of proof in this regard falling on the shoulders of the accused. In practice, this is an intolerably onerous burden.

In sum, the behemoth of the Commission is destructive of the foundations of civil liberty.

IV. Remoteness of Causal Nexus

One of the reasons why the law is indefensibly wide in its operation is the imposition of criminal liability for consequences which are not proximately linked to the conduct of the accused.It is declared to be an offence to communicate “a false statement which gives provocation to any person or incites any person, intending or knowing it to be likely that such provocation or incitement will cause the offence of rioting to be committed” (section 14).

In the envisaged situation, rioting is committed by a third party. Criminal liability on the part of the person communicating through an online account or online location, is grounded solely in assumed knowledge of likely behaviour of the third party. Indeed, criminal liability of the communicator is established, even when the consequence of rioting does not take place at all, the only difference being reduction of sentence (section 14 (f)). Similarly, the communicator of the statement is held criminally responsible for disturbance of a religious assembly, with no clear nexus being insisted upon between the act of the accused and the rioting which takes place (section 15)).

The net of criminal liability is cast far too wide by this approach, the lack of a sufficiently clear causal nexus being the underlying defect.

V. Expanding Frontiers of Criminalisation

A prominent feature of the Online Safety Act is the indiscriminate use of criminal sanctions to attain its objectives. A wide range of offences is created by Part III of the legislation. Many of these are of amorphous scope, lacking in precise definition of constituent elements – for example, “wantonly” giving provocation by a false statement to cause riot (section 14), “voluntarily” causing disturbance to a religious assembly (section 15) and “malicious” communication of a false statement to outrage religious feelings (section 16). The ambit of the offence against “public tranquillity” (section 19) is equally unclear. These are all offences which carry deterrent sentences of imprisonment, in one case for up to 3 years and in the other for a maximum of 7 years, in addition to, or as an alternative to, a substantial fine.

The Commission, on satisfaction that an offence has been committed under the Act, is empowered to “take steps to initiate criminal proceedings in terms of s. 136 of the Code of Criminal Procedure Act, No. 15 of 1979” (section 38(2)). Moreover, every offence established by the Act is characterised as a non-cognisable offence within the meaning of the laws governing criminal procedure (section 43(a)).

Penal consequences of daunting severity are visited upon bodies corporate. Every director or other principal officer is held criminally responsible (section 44(a)). If the offender is a firm, criminal liability is imposed on every partner of the firm (section 44(b)) and, in the case of an unincorporated body, “every individual who is a controlling member and every principal officer responsible for management and control” (section 44(c)) is exposed to criminal sanctions. Lack of knowledge or exercise of due diligence is recognised as an exculpatory circumstance but, in keeping with general evidentiary principles, the burden of proof in this regard is borne by the accused.

VI. Chilling Effect of the Law

The core of the statute resides in the powers vested in the Commission, to apply an extensive range of measures to deal with “prohibited statements” (Part II). These include orders “to stop the communication of such statements” (section 11 (b)), “to disable access to an online location” (section 11 (c)) and to direct removal of prohibited statements (section 11 (e)). A worrying factor is the absence of a proper definition of “prohibited statements”, the purported definition consisting merely of a reference to the provisions which use the phrase (section 52).

When the Commission is satisfied that a “prohibited statement” has been made, its coercive powers which come into play, are of a drastic nature. These extend to the authority to issue a notice to the communicator of the statement, ordering the adoption of measures to prevent circulation (section 23 (f)). This renders applicable the draconian provision that the recipient of the notice “shall comply with such notice immediately but not later than 24 hours from such notice” (section 23 (b) and (f)). Failure results in criminal proceedings in a Magistrate’s Court (section 23 (g)).

The Commission has power to name an online location as a “declared online location” if 3 or more prohibited statements have been communicated on that location to end users in Sri Lanka (section 28 (i)). An internet service provider or an internet intermediary, on the making of such a declaration by the Commission, is obliged to cease communication instantly on pain of imprisonment for a term of up to 7 years or a maximum fine of 10 million rupees, the penalty being doubled in the event of a subsequent offence (section 29 (6)).

Especially in light of the broad definition of “inauthentic online account”, “internet service provider”, “internet intermediary” and “internet intermediary service” (section 52), the chilling effect of the law is evident.

It is hardly surprising, then, that prominent internet and technology companies active in Sri Lanka, in their response to the legislation, have sounded a strong note of caution, even indicating the risk of withdrawal from their operations in our country.

The Asian Internet Coalition (AIC) which consists of 13 companies of international stature, commenting on this legislation when it was in Bill form, declared: “Despite our commitment to constructive collaboration, the AIC has not been privy to proposed amendments to the Bill. We unequivocally stand by our position that the Online Safety Bill, in its current form, is unworkable and would undermine potential growth and direct foreign investment into Sri Lanka’s digital economy. We firmly believe that for the Bill to align with global best practices, extensive revisions are imperative” (Emergency Media Statement of 23 January 2024).

This can hardly be disregarded in cavalier fashion.As the government has emphatically acknowledged, digitalization and other technology innovations are central to current plans for economic development and, of equal importance, for ensuring equitable distribution of the benefits of progress. Swift and ready access to market information – be it for farmers, the fishing community, manufacturers of industrial products, providers of services and the small and medium sector in particular – is an indispensable requirement for the success of current strategies. If companies of the calibre of Facebook, Google,X,Apple,Amazon,Cloudflare and Yahoo,contemplate discontinuation of their services because of the oppressive character of the law, economic development, far from being advanced, is certain to be retarded.

VII. The Need for Imperative Change

Parliament debated the Online Safety Bill for 2 full days on 23 and 24 February 2024. Pervasive deficiencies of the law were convincingly identified during this rich and rewarding debate. No one was more forthright than the current Prime Minister, Dr. Harini Amarasuriya, at that time speaking from the ranks of the Opposition, in her unreserved condemnation of the Bill and her strident call for its withdrawal: “The intent of the Government is clear. It is about controlling dissent; it is about taking control of public discourse or public narrative at a crucial time in this country when democracy needs to be protected at all costs. That every instrument is gong to be used to stifle dissent, is very clear” (Hansard of 24 January 2024, Column 224).

The Online Safety Act stands as a monument to illiberalism and as an anchor of State apparatus infringing the substance of civil liberty. Its removal from the statute laws of our country is a dire necessity, no longer to be delayed.

By Professor G. L. Peiris

By Professor G. L. Peiris

D. Phil. (Oxford), Ph. D.

(Sri Lanka);

Rhodes Scholar,Quondam Visiting Fellow of the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge and London;

Former Vice-Chancellor and Emeritus Professor of Law of the University of Colombo.

Opinion

Buddhist insights into the extended mind thesis – Some observations

It is both an honour and a pleasure to address you on this occasion as we gather to celebrate International Philosophy Day. Established by UNESCO and supported by the United Nations, this day serves as a global reminder that philosophy is not merely an academic discipline confined to universities or scholarly journals. It is, rather, a critical human practice—one that enables societies to reflect upon themselves, to question inherited assumptions, and to navigate periods of intellectual, technological, and moral transformation.

In moments of rapid change, philosophy performs a particularly vital role. It slows us down. It invites us to ask not only how things work, but what they mean, why they matter, and how we ought to live. I therefore wish to begin by expressing my appreciation to UNESCO, the United Nations, and the organisers of this year’s programme for sustaining this tradition and for selecting a theme that invites sustained reflection on mind, consciousness, and human agency.

We inhabit a world increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence, neuroscience, cognitive science, and digital technologies. These developments are not neutral. They reshape how we think, how we communicate, how we remember, and even how we imagine ourselves. As machines simulate cognitive functions once thought uniquely human, we are compelled to ask foundational philosophical questions anew:

What is the mind? Where does thinking occur? Is cognition something enclosed within the brain, or does it arise through our bodily engagement with the world? And what does it mean to be an ethical and responsible agent in a technologically extended environment?

Sri Lanka’s Philosophical Inheritance

On a day such as this, it is especially appropriate to recall that Sri Lanka possesses a long and distinguished tradition of philosophical reflection. From early Buddhist scholasticism to modern comparative philosophy, Sri Lankan thinkers have consistently engaged questions concerning knowledge, consciousness, suffering, agency, and liberation.

Within this modern intellectual history, the University of Peradeniya occupies a unique place. It has served as a centre where Buddhist philosophy, Western thought, psychology, and logic have met in creative dialogue. Scholars such as T. R. V. Murti, K. N. Jayatilleke, Padmasiri de Silva, R. D. Gunaratne, and Sarathchandra did not merely interpret Buddhist texts; they brought them into conversation with global philosophy, thereby enriching both traditions.

It is within this intellectual lineage—and with deep respect for it—that I offer the reflections that follow.

Setting the Philosophical Problem

My topic today is “Embodied Cognition and Viññāṇasota: Buddhist Insights on the Extended Mind Thesis – Some Observations.” This is not a purely historical inquiry. It is an attempt to bring Buddhist philosophy into dialogue with some of the most pressing debates in contemporary philosophy of mind and cognitive science.

At the centre of these debates lies a deceptively simple question: Where is the mind?

For much of modern philosophy, the dominant answer was clear: the mind resides inside the head. Thinking was understood as an internal process, private and hidden, occurring within the boundaries of the skull. The body was often treated as a mere vessel, and the world as an external stage upon which cognition operated.

However, this picture has increasingly come under pressure.

The Extended Mind Thesis and the 4E Turn

One of the most influential challenges to this internalist model is the Extended Mind Thesis, proposed by Andy Clark and David Chalmers. Their argument is provocative but deceptively simple: if an external tool performs the same functional role as a cognitive process inside the brain, then it should be considered part of the mind itself.

From this insight emerges the now well-known 4E framework, according to which cognition is:

Embodied – shaped by the structure and capacities of the body

Embedded – situated within physical, social, and cultural environments

Enactive – constituted through action and interaction

Extended – distributed across tools, artefacts, and practices

This framework invites us to rethink the mind not as a thing, but as an activity—something we do, rather than something we have.

Earlier Western Challenges to Internalism

It is important to note that this critique of the “mind in the head” model did not begin with cognitive science. It has deep philosophical roots.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

famously warned philosophers against imagining thought as something occurring in a hidden inner space. Such metaphors, he suggested, mystify rather than clarify our understanding of mind.

Similarly, Franz Brentano’s notion of intentionality—his claim that all mental states are about something—shifted attention away from inner substances toward relational processes. This insight shaped Husserl’s phenomenology, where consciousness is always world-directed, and Freud’s psychoanalysis, where mental life is dynamic, conflicted, and socially embedded.

Together, these thinkers prepared the conceptual ground for a more process-oriented, relational understanding of mind.

Varela and the Enactive Turn

A decisive moment in this shift came with Francisco J. Varela, whose work on enactivism challenged computational models of mind. For Varela, cognition is not the passive representation of a pre-given world, but the active bringing forth of meaning through embodied engagement.

Cognition, on this view, arises from the dynamic coupling of organism and environment. Importantly, Varela explicitly acknowledged his intellectual debt to Buddhist philosophy, particularly its insights into impermanence, non-self, and dependent origination.

Buddhist Philosophy and the Minding Process

Buddhist thought offers a remarkably sophisticated account of mind—one that is non-substantialist, relational, and processual. Across its diverse traditions, we find a consistent emphasis on mind as dependently arisen, embodied through the six sense bases, and shaped by intention and contact.

Crucially, Buddhism does not speak of a static “mind-entity”. Instead, it employs metaphors of streams, flows, and continuities, suggesting a dynamic process unfolding in relation to conditions.

Key Buddhist Concepts for Contemporary Dialogue

Let me now highlight several Buddhist concepts that are particularly relevant to contemporary discussions of embodied and extended cognition.

The notion of prapañca, as elaborated by Bhikkhu Ñāṇananda, captures the mind’s tendency toward conceptual proliferation. Through naming, interpretation, and narrative construction, the mind extends itself, creating entire experiential worlds. This is not merely a linguistic process; it is an existential one.

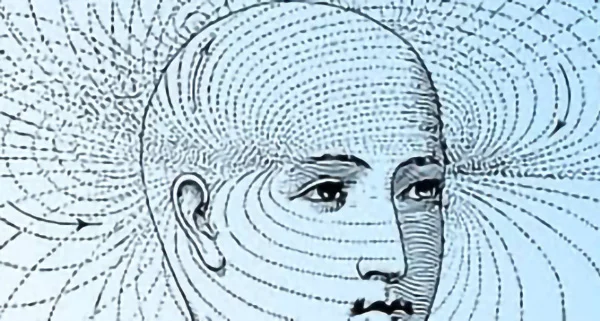

The Abhidhamma concept of viññāṇasota, the stream of consciousness, rejects the idea of an inner mental core. Consciousness arises and ceases moment by moment, dependent on conditions—much like a river that has no fixed identity apart from its flow.

The Yogācāra doctrine of ālayaviññāṇa adds a further dimension, recognising deep-seated dispositions, habits, and affective tendencies accumulated through experience. This anticipates modern discussions of implicit cognition, embodied memory, and learned behaviour.

Finally, the Buddhist distinction between mindful and unmindful cognition reveals a layered model of mental life—one that resonates strongly with contemporary dual-process theories.

A Buddhist Cognitive Ecology

Taken together, these insights point toward a Buddhist cognitive ecology in which mind is not an inner object but a relational activity unfolding across body, world, history, and practice.

As the Buddha famously observed, “In this fathom-long body, with its perceptions and thoughts, I declare there is the world.” This is perhaps one of the earliest and most profound articulations of an embodied, enacted, and extended conception of mind.

Conclusion

The Extended Mind Thesis challenges the idea that the mind is confined within the skull. Buddhist philosophy goes further. It invites us to reconsider whether the mind was ever “inside” to begin with.

In an age shaped by artificial intelligence, cognitive technologies, and digital environments, this question is not merely theoretical. It is ethically urgent. How we understand mind shapes how we design technologies, structure societies, and conceive human responsibility.

Buddhist philosophy offers not only conceptual clarity but also ethical guidance—reminding us that cognition is inseparable from suffering, intention, and liberation.

Dr. Charitha Herath is a former Member of Parliament of Sri Lanka (2020–2024) and an academic philosopher. Prior to entering Parliament, he served as Professor (Chair) of Philosophy at the University of Peradeniya. He was Chairman of the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) from 2020 to 2022, playing a key role in parliamentary oversight of public finance and state institutions. Dr. Herath previously served as Secretary to the Ministry of Mass Media and Information (2013–2015) and is the Founder and Chair of Nexus Research Group, a platform for interdisciplinary research, policy dialogue, and public intellectual engagement.

He holds a BA from the University of Peradeniya (Sri Lanka), MA degrees from Sichuan University (China) and Ohio University (USA), and a PhD from the University of Kelaniya (Sri Lanka).

(This article has been adapted from the keynote address delivered

by Dr. Charitha Herath

at the International Philosophy Day Conference at the University of Peradeniya.)

Opinion

We do not want to be press-ganged

Reference ,the Indian High Commissioner’s recent comments ( The Island, 9th Jan. ) on strong India-Sri Lanka relationship and the assistance granted on recovering from the financial collapse of Sri Lanka and yet again for cyclone recovery., Sri Lankans should express their thanks to India for standing up as a friendly neighbour.

On the Defence Cooperation agreement, the Indian High Commissioner’s assertion was that there was nothing beyond that which had been included in the text. But, dear High Commissioner, we Sri Lankans have burnt our fingers when we signed agreements with the European nations who invaded our country; they took our leaders around the Mulberry bush and made our nation pay a very high price by controlling our destiny for hundreds of years. When the Opposition parties in the Parliament requested the Sri Lankan government to reveal the contents of the Defence agreements signed with India as per the prevalent common practice, the government’s strange response was that India did not want them disclosed.

Even the terms of the one-sided infamous Indo-Sri Lanka agreement, signed in 1987, were disclosed to the public.

Mr. High Commissioner, we are not satisfied with your reply as we are weak, economically, and unable to clearly understand your “India’s Neighbourhood First and Mahasagar policies” . We need the details of the defence agreements signed with our government, early.

RANJITH SOYSA

Opinion

When will we learn?

At every election—general or presidential—we do not truly vote, we simply outvote. We push out the incumbent and bring in another, whether recycled from the past or presented as “fresh.” The last time, we chose a newcomer who had spent years criticising others, conveniently ignoring the centuries of damage they inflicted during successive governments. Only now do we realise that governing is far more difficult than criticising.

There is a saying: “Even with elephants, you cannot bring back the wisdom that has passed.” But are we learning? Among our legislators, there have been individuals accused of murder, fraud, and countless illegal acts. True, the courts did not punish them—but are we so blind as to remain naive in the face of such allegations? These fraudsters and criminals, and any sane citizen living in this decade, cannot deny those realities.

Meanwhile, many of our compatriots abroad, living comfortably with their families, ignore these past crimes with blind devotion and campaign for different parties. For most of us, the wish during an election is not the welfare of the country, but simply to send our personal favourite to the council. The clearest example was the election of a teledrama actress—someone who did not even understand the Constitution—over experienced and honest politicians.

It is time to stop this bogus hero worship. Vote not for personalities, but for the country. Vote for integrity, for competence, and for the future we deserve.

Deshapriya Rajapaksha

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

News3 days ago

News3 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II