Features

Rebuilding Sri Lanka for the long term

The government is rebuilding the cyclone-devastated lives, livelihoods and infrastructure in the country after the immense destruction caused by Cyclone Ditwah. President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has been providing exceptional leadership by going into the cyclone affected communities in person, to mingle directly with the people there and to offer encouragement and hope to them. A President who can be in the midst of people when they are suffering and in sorrow is a true leader. In a political culture where leaders have often been distant from the everyday hardships of ordinary people, this visible presence would have a reassuring psychological effect.

The international community appears to be comfortable with the government and has been united in giving it immediate support. Whether it be Indian and US helicopters that provided essential airlift capacity or cargo loads of relief material that have come from numerous countries, or funds raised from the people of tiny Maldives, the support has given Sri Lankans the sense of being a part of the world family. The speed and breadth of this response has contrasted sharply with the isolation Sri Lanka experienced during some of the darker moments of its recent past.

There is no better indicator of the international goodwill to Sri Lanka as in the personal donations for emergency relief that have been made by members of the diplomatic corps in Sri Lanka. Such gestures go beyond formal diplomacy and suggest a degree of personal confidence in the direction in which the country is moving. The office of the UN representative in Sri Lanka has now taken the initiative to launch a campaign for longer term support, signalling that emergency assistance can be a bridge to sustained engagement rather than a one-off intervention.

Balanced Statement

In a world that has turned increasingly to looking after narrow national interests rather than broad common interests, Sri Lanka appears to have found a way to obtain the support of all countries. It has received support from countries that are openly rivals to each other. This rare convergence reflects a perception that Sri Lanka is not seeking to play one power against another, and balancing them, but rather to rebuild itself on the basis of stability, inclusiveness and responsible governance.

An excerpt from an interview that President Dissanayake gave to the US based Newsweek magazine is worth reproducing. In just one paragraph he has summed up Sri Lankan foreign policy that can last the test of time. A question Newsweek put to the president was: “Sri Lanka sits at the crossroads of Chinese built infrastructure, Indian regional influence and US economic leverage. To what extent does Sri Lanka truly retain strategic autonomy, and how do you balance these relationships?”

The president replied: “India is Sri Lanka’s closest neighbour, separated by about 24 km of ocean. We have a civilisational connection with India. There is hardly any aspect of life in Sri Lanka that is not connected to India in some way or another. India has been the first responder whenever Sri Lanka has faced difficulty. India is also our largest trading partner, our largest source of tourism and a significant investor in Sri Lanka. China is also a close and strategic partner. We have a long historic relationship—both at the state level and at a political party level. Our trade, investment and infrastructure partnership is very strong. The United States and Sri Lanka also have deep and multifaceted ties. The US is our largest market. We also have shared democratic values and a commitment to a rules-based order. We don’t look at our relations with these important countries as balancing. Each of our relationships is important to us. We work with everyone, but always with a single purpose – a better world for Sri Lankans, in a better world for all.”

Wider Issues

The President’s articulation of foreign relations, especially the underlying theme of working with everyone for the wellbeing of all, resonates strongly in the context of the present crisis. The willingness of all major partners to assist Sri Lanka simultaneously suggests that goodwill generated through effective disaster response can translate into broader political and diplomatic space. Within the country, the government has been successful in calling for and in obtaining the support of civil society which has an ethos of filling in gaps by seeking the inclusion of marginalised groups and communities who may be left out of the mainstream of development.

Civil society organisations have historically played a crucial role in Sri Lanka during times of crisis, often reaching communities that state institutions struggle to access. Following a meeting with CSOs, at which the president requested their support and assured them of their freedom to choose, the CSOs mobilised in all flood affected parts of the country, many of them as part of a CSO Collective for Emergency Response. An important initiative was to undertake the task of ascertaining the needs of the cyclone affected people. Volunteers from a number of civil society groups fanned out throughout the country to collect the necessary information. This effort helped to ground relief efforts in real needs rather than assumptions, reducing duplication and ensuring that assistance reached those most affected.

The priority that the government is currently having to give to post-cyclone rebuilding must not distract it from giving priority attention to dealing with postwar issues. The government has the ability and value-system to resolve other national problems. Resolving issues of post disaster rebuilding in the aftermath of the cyclone have commonalities in relation to the civil war that ended in 2009. The failure of successive governments to address those issues has prompted the international community to continuously question and find fault with Sri Lanka at the UN. This history has weighed heavily on Sri Lanka’s international standing and has limited its ability to fully leverage external support.

Required Urgency

At a time when the international community is demonstrating enormous goodwill to Sri Lanka, the lessons learnt from their own experiences, and the encouraging support they are giving Sri Lanka at present, can and must be utilised. The government under President Dissanayake has committed to a non-racist Sri Lanka in which all citizens will be treated equally. The experience of other countries, such as the UK, India, Switzerland, Canada and South Africa show that problems between ethnic communities also require inter community power sharing in the form of devolution of power. Countries that have succeeded in reconciling diversity with unity have done so by embedding inclusion into governance structures rather than treating it as a temporary concession.

Sri Lanka’s present moment of international goodwill provides a rare opening to learn from these experiences with the encouragement and support of its partners, including civil society which has shown its readiness to join hands with the government in working for the people’s wellbeing. The unresolved problems of land resettlement, compensation for lost lives and homes, finding the truth about missing persons continue to weigh heavily on the minds and psyche of people in the former war zones of the north and east even as they do so for the more recent victims of the cyclone.

Unresolved grievances do not disappear with time. They resurface periodically, often in moments of political transition or social stress, undermining national cohesion. The government needs to ensure sustainable solutions not only to climate related development, but also to ethnic peace and national reconciliation. The government needs to bring together the urgency of disaster recovery with the long-postponed task of political reform as done in the Indonesian province of Aceh in the aftermath of the 2004 tsunami for which it needs bipartisan political support. Doing so could transform a national tragedy into a turning point for long lasting unity and economic take-off.

by Jehan Perera

Features

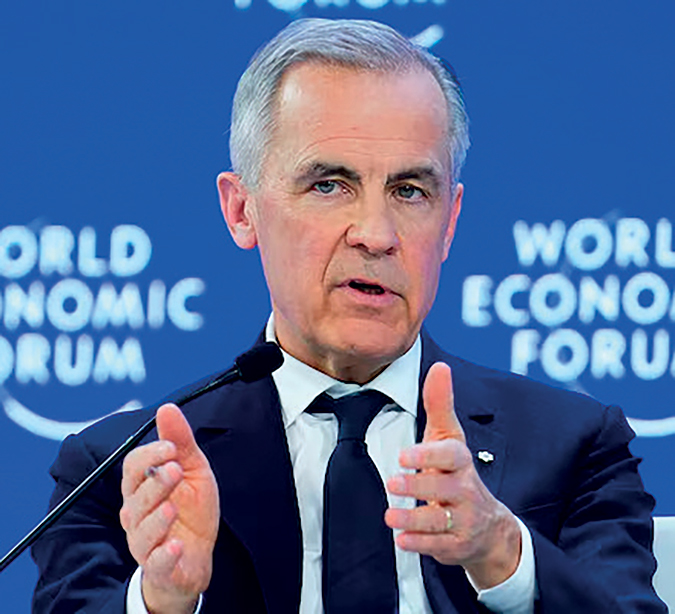

Seething Global Discontents and Sri Lanka’s Tea Cup Storms

Global temperatures in January have been polar opposite – plus 50 Celsius down under in Australia, and minus 45 Celsius up here in North America (I live in Canada). Between extremes of many kinds, not just thermal, the world order stands ruptured. That was the succinct message in what was perhaps the most widely circulated and listened to speeches of this century, delivered by Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney at Davos, in January. But all is not lost. Who seems to be getting lost in the mayhem of his own making is Donald Trump himself, the President of the United States and the world’s disruptor in chief.

After a year of issuing executive orders of all kinds, President Trump is being forced to retreat in Minneapolis, Minnesota, by the public reaction to the knee-jerk shooting and killing of two protesters in three weeks by federal immigration control and border patrol agents. The latter have been sent by the Administration to implement Trump’s orders for the arbitrary apprehension of anyone looking like an immigrant to be followed by equally arbitrary deportation.

The Proper Way

Many Americans are not opposed to deporting illegal and criminal immigrants, but all Americans like their government to do things the proper way. It is not the proper way in the US to send federal border and immigration agents to swarm urban neighbourhood streets and arrest neighbours among neighbours, children among other school children, and the employed among other employees – merely because they look different, they speak with an accent, or they are not carrying their papers on their person.

Americans generally swear by the Second Amendment and its questionably interpretive right allowing them to carry guns. But they have no tolerance when they see government forces turn their guns on fellow citizens. Trump and his administration cronies went too far and now the chickens are coming home to roost. Barely a month has passed in 2026, but Trump’s second term has already run into multiple storms.

There’s more to come between now and midterm elections in November. In the highly entrenched American system of checks and balances it is virtually impossible to throw a government out of office – lock, stock and barrel. Trump will complete his term, but more likely as a lame duck than an ordering executive. At the same time, the wounds that he has created will linger long even after he is gone.

Equally on the external front, it may not be possible to immediately reverse the disruptions caused by Trump after his term is over, but other countries and leaders are beginning to get tired of him and are looking for alternatives bypassing Trump, and by the same token bypassing the US. His attempt to do a Venezuela over Greenland has been spectacularly pushed back by a belatedly awakening Europe and America’s other western allies such as Australia, Canada and New Zealand. The wags have been quick to remind us that he is mostly a TACO (Trump always chickens out) Trump.

Grandiose Scheme or Failure

His grandiose scheme to establish a global Board of Peace with himself as lifetime Chair is all but becoming a starter. No country or leader of significant consequence has accepted the invitation. The motley collection of acceptors includes five East European countries, three Central Asian countries, eight Middle Eastern countries, two from South America, and four from Asia – Cambodia, Vietnam, Indonesia and Pakistan. The latter’s rush to join the club will foreclose any chance of India joining the Board. Countries are allowed a term of three years, but if you cough up $1 billion, could be member for life. Trump has declared himself to be lifetime chair of the Board, but he is not likely to contribute a dime. He might claim expenses, though. The Board of Peace was meant to be set up for the restoration of Gaza, but Trump has turned it into a retirement project for himself.

There is also the ridiculous absurdity of Trump continuing as chair even after his term ends and there is a different president in Washington. How will that arrangement work? If the next president turns out to be a Democrat, Trump may deny the US a seat on the board, cash or no cash. That may prove to be good for the UN and its long overdue restructuring. Although Trump’s Board has raised alarms about the threat it poses to the UN, the UN may end up being the inadvertent beneficiary of Trump’s mercurial madness.

The world is also beginning to push back on Trump’s tariffs. Rather, Trump’s tariffs are spurring other countries to forge new trade alliances and strike new trade deals. On Tuesday, India and EU struck the ‘mother of all’ trade deals between them, leaving America the poorer for it. Almost the next day , British Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer and Chinese leader Xi Jinping announced in Beijing that they had struck a string of deals on travel, trade and investments. “Not a Big Bang Free Trade Deal” yet, but that seems to be the goal. The Canadian Prime Minister has been globe-trotting to strike trade deals and create investment opportunities. He struck a good reciprocal deal with China, is looking to India, and has turned to South Korea and a consortium from Germany and Norway to submit bids for a massive submarine supply contract supplemented by investments in manufacturing and mineral industries. The informal first-right-of-refusal privilege that US had in Canada for defense contracts is now gone, thanks to Trump.

The disruptions that Trump has created in the world order may not be permanent or wholly irreversible, as Prime Minister Carney warned at Davos. But even the short term effects of Trump’s disruptions will be significant to all of US trading partners, especially smaller countries like Sri Lanka. Regardless of what they think of Trump, leaders of governments have a responsibility to protect their citizens from the negative effects of Trump’s tariffs. That will be in addition to everything else that governments have to do even if they do not have Trump’s disruptions to deal with.

Bland or Boisterous

Against the backdrop of Trump-induced global convulsions, politics in Sri Lanka is in a very stable mode. This is not to diminish the difficulties and challenges that the vast majority of Sri Lankans are facing – in meeting their daily needs, educating their children, finding employment for the youth, accessing timely health care and securing affordable care for the elderly. The challenges are especially severe for those devastated by cyclone Ditwah.

Politically, however, the government is not being tested by the opposition. And the once boisterous JVP/NPP has suddenly become ‘bland’ in government. “Bland works,” is a Canadian political quote coined by Bill Davis a nationally prominent premier of the Province of Ontario. Davis was responding to reporters looking for dramatic politics instead of boring blandness. He was Premier of Ontario for 14 years (1971-1985) and won four consecutive elections before retiring.

No one knows for how long the NPP government will be in power in Sri Lanka or how many more elections it is going to win, but there is no question that the government is singularly focused on winning the next parliamentary election, or both the presidential and parliamentary elections – depending on what happens to the system of directly electing the executive president.

The government is trying to grow comfortable in being on cruise control to see through the next parliamentary election. Its critics on the other hand, are picking on anything that happens on any day to blame or lampoon the government. The government for all its tight control of its members and messaging is not being able to put out quickly the fires that have been erupting. There are the now recurrent matters of the two AGs (non-appointment of the Auditor General and alleged attacks on the Attorney General) and the two ERs (Educational Reform and Electricity Reform), the timing of the PC elections, and the status of constitutional changes to end the system of directly electing the president.

There are also criticisms of high profile resignations due to government interference and questionable interdictions. Two recent resignations have drawn public attention and criticism, viz., the resignation of former Air Chief Marshal Harsha Abeywickrama from his position as the Chairman of Airport & Aviation Services, and the earlier resignation of Attorney-at-Law Ramani Jayasundara from her position as Chair of the National Women’s Commission. Both have been attributed to political interferences. In addition, the interdiction of the Deputy Secretary General of Parliament has also raised eyebrows and criticisms. The interdiction in parliament could not have come at a worse time for the government – just before the passing away of Nihal Seniviratne, who had served Sri Lanka’s parliament for 33 years and the last 13 of them as its distinguished Secretary General.

In a more political sense, echoes of the old JVP boisterousness periodically emanate in the statements of the JVP veteran and current Cabinet Minister K.D. Lal Kantha. Newspaper columnists love to pounce on his provocative pronouncements and make all manner of prognostications. Mr. Lal Kantha’s latest reported musing was that: “It is true our government is in power, but we still don’t have state power. We will bring about a revolution soon and seize state power as well.”

This was after he had reportedly taken exception to filmmaker Asoka Handagama’s one liner: “governing isn’t as easy as it looks when you are in the opposition,” and allegedly threatened to answer such jibes no matter who stood in the way and what they were wearing “black robes, national suits or the saffron.” Ironically, it was the ‘saffron part’ that allegedly led to the resignation of Harsha Abeywickrama from the Airport & Aviation Services. And President AKD himself has come under fire for his Thaipongal Day statement in Jaffna about Sinhala Buddhist pilgrims travelling all the way from the south to observe sil at the Tiisa Vihare in Thayiddy, Jaffna.

The Vihare has been the subject of controversy as it was allegedly built under military auspices on the property of local people who evacuated during the war. Being a master of the spoken word, the President could have pleaded with the pilgrims to show some sensitivity and empathy to the displaced Tamil people rather than blaming them (pilgrims) of ‘hatred.’ The real villains are those who sequestered property and constructed the building, and the government should direct its ire on them and not the pilgrims.

In the scheme of global things, Sri Lanka’s political skirmishes are still teacup storms. Yet it is never nice to spill your tea in public. Public embarrassments can be politically hurtful. As for Minister Lal Kantha’s distinction between governmental mandate and state power – this is a false dichotomy in a fundamentally practical sense. He may or may not be aware of it, but this distinction quite pre-occupied the ideologues of the 1970-75 United Front government. Their answer of appointing Permanent Secretaries from outside the civil service was hardly an answer, and in some instances the cure turned out to be worse than the disease.

As well, what used to be a leftist pre-occupation is now a right wing insistence especially in America with Trump’s identification of the so called ‘deep state’ as the enemy of the people. I don’t think the NPP government wants to go there. Rather, it should show creative originality in making the state, whether deep or shallow, to be of service to the people. There is a general recognition that the government has been doing just that in providing redress to the people impacted by the cyclone. A sign of that recognition is the number of people contributing to the disaster relief fund and in substantial amounts. The government should not betray this trust but build on it for the benefit of all. And better do it blandly than boisterously.

by Rajan Philips

Features

The historical context of Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict

The themes of power-sharing, devolution, and federalism, which run through this work, have their origin in issues which are not connected to ethnicity. Indeed, federalism, as a structure of governance suited to Sri Lanka, was first proposed in an entirely different setting. At its inception, this had to do with the aspirations not of the Tamils, but of the Kandyan Sinhalese.

The Donoughmore Commission

A watershed in the Island’s constitutional development was the Donoughmore Commission which arrived on our shores in November, 1927. The Kandyan National Assembly, in their representations to the Commission, declared: “Ours is not a communal claim or a claim for the aggrandizement of a few. It is a claim of a nation to live its own life and realize its own destiny. A federal system will enable the respective nationals of the several states to prevent further inroads into their territories and to build up their own nationality.”

This had been foreshadowed during the years leading up to the appointment of the Donoughmore Commission by representations on similar lines by prominent Sinhala representatives of the Ceylon National Congress. An exemplar was S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, fresh from his 1laurels at Oxford, who, in a lecture delivered to the Students’ Congress in Jaffna on 17 July 1926, went so far as to characterize federalism as the “only solution to our political problems.” The lecture was the culmination of a line of argument which he had developed persuasively in six letters to The Ceylon Morning Leader, published between 19 May, and 30 June, 1926.

The Donoughmore Commissioners were not friendly to the idea of federalism because of their robust aversion to division along communal or other lines, and their commitment, as the foundation of their report, to unity of the body politic. A nuanced approach typified their recommendations, in so far as they showed themselves well disposed to the concept of Provincial Councils. They accepted the system in principle, although inclined to leave the modalities of implementation to an elected administration.

It is interesting to note that, almost a 100 years ago, the Donoughmore Commissioners showed sensitivity to a range of issues which gave rise to vigorous and even acrimonious debate in succeeding decades. Among these was a nexus between Provincial Councils and local government institutions, and the question whether Members of Parliament should be eligible to sit in Provincial Councils. On this latter issue, as recently as two years ago, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe, citing copious precedents, strongly contended for the view that there should be no constitutional or statutory bar.

Incipient indications of ethnic identity emerging as an impediment to the growth of a healthy multi-party system proved to be a source of anxiety to the Donoughmore Commissioners. This accounted for their decision to spend several days in Jaffna and Batticaloa to listen to the views of a cross-section of the public there. Organizations which made representations to the Commission included the All Ceylon Tamil Congress and The Jaffna Association. The Commissioners were alive, as well, to burgeoning communal tensions within the Ceylon National Congress.

A Marxist-Leninist perspective

The impetus towards federalism had a strong ideological perspective, from a Marxist-Leninist standpoint. This was vividly mirrored in the policy articulated by the Ceylon Trade Union Federation on 23 September 1944, on which was built the constitutional proposals addressed by the Communist Party to the Ceylon National Congress on 18 October 1944. Subject to minor refinements and matters of detail, the two documents can be taken together. They go very far, indeed. Anticipating future developments, merger of the North East was specifically contemplated.

The nomenclature used had much in common with the current discourse. The Sinhalese and the Tamils were envisioned as two distinct “nations”, or “historically evolved nationalities”. The homeland concept found expression in relation to a contiguous territory. This was thought to be justified on the basis that the distinct nationalities “have their own language, economic life, culture, and psychological makeup.”

The high water mark of the proposals was the assertion that “Both nationalities have their right to self-determination, including the right, if they so desire, to form their own separate independent state.” The sheet anchor of the proposals was that the equality and sovereignty of the “peoples” of Ceylon must be recognized. These were among the ideas that found unanimous acceptance at the Town Hall rally on 15 October1944.

The Communist Party’s proposals not only gave expression to these normative principles, but spelt out practical means for arriving within the legislature. This was embodied in the proposal relating to two Chambers enjoying coeval authority. The Chamber of Representatives was to be elected on the basis of territorial constituencies buttressed by universal adult franchise, while the second Chamber, designated the Chamber of Nationalities, was marked by the special feature of the principle of equality between the nationalities.

These proposals received further elaboration in a memorandum submitted to the Working Committee of the Ceylon National Congress by two prominent members of the Communist Party, Mr. Pieter Keuneman and Mr. A. Vaidialingam. The thrust of their reasoning was predicated on a multinational state with inbuilt safeguards for the “non- dominant nationality”. The premise was set out pithily as follows: “We regard a nation as a historical, as opposed to an ethnographical, concept. It is a historically evolved, stable community of people living in a contiguous territory as their traditional homeland.”

The Soulbury Commission

These events occurred in the immediate backdrop to the transition from colonial to dominion status. A Commission headed by Lord Soulbury, appointed by Whitehall to consider the grant of full independence to Ceylon, arrived in the country in December, 1944. The main focus of their work was intended to be a comprehensive set of proposals prepared by the Board of Ministers, which functioned under the Donoughmore Constitution. This was in response to the Declaration of May, 1943, made by Mr. Oliver Stanley, Secretary of State for the Colonies, setting out, in outline, the intentions of the British government.

Some degree of friction arose, however, because of the subsequent exhortation to the Soulbury Commission “to consult with various interests including minority communities” interpreted by the Board of Ministers as a breach of faith, in that it deviated from the previous assurance that the Commission’s mandate would be confined to consideration of the Memorandum to be submitted by the Ministers. It was possible, however, to arrive at a pragmatic compromise, in terms of which the Ministers, although boycotting formal sessions with the Commission, made their views known extensively during frequent social interactions.

Their proposals were contained in the ‘Ministers’ draft’, which was mainly the work of Sir Ivor Jennings, a renowned constitutional expert, later to become Vice-Chancellor of the University of Ceylon, in close consultation with Mr D. S. Senanayake and Sir Oliver Goonetilleke. The report of the Soulbury Commission, based primarily on the Ministers’ draft, was published in 1945 as a White Paper, which formed the foundation of the three legal instruments comprising the Constitution of Ceylon of 1948.

An interesting feature of the work of the Soulbury Commission was explicit recognition of the complexity of inter-communal relations on the Island and the near- insoluble difficulties they posed in respect of constitutional development. The Commission showed candour in its observation that “The relations of the minorities – the Ceylon Tamils, the Indian Tamils, Muslims, Burghers, and Europeans with the Sinhalese majority – present the most difficult of the many problems involved in the reform of the Constitution of Ceylon.”

The Soulbury Commission found itself subject to rival pressures of the greatest intensity. The Board of Ministers had graduated from their efforts directed at amendment of the Donoughmore Constitution to a full-blooded demand for dominion status. The countervailing pressure came from the leadership of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress, which strenuously contendedc omplete transference of power and authority from neutral British hands to the people of this country is causing, in the minds of the Tamil people, “in common with other minorities, much misgiving and fear.”

The most significant aspect of the Soulbury Commission’s initiatives consisted of the search for mediating techniques to discourage polarization. On the whole, this effort was marked by commendable pragmatism. It is of interest that the Commissioners, invited to consider in earnest the federal route, had little fascination for it, nor did the idea of a Bill of Rights find favour with them. If the underlying fear related to encroachment of seminal rights by capricious legislative action, this anxiety could have been convincingly assuaged by enshrining in the Constitution a nucleus of rights placed beyond the reach of the legislature.

This expedient would have been effective, if combined with appropriate mechanisms of judicial review. In line with this approach, it would be an important part of the judicial function, exercised by the Apex Court, to rule on the issue of incompatibility of impugned legislation with paramount safeguards embodied in the Constitution.

The Soulbury Commissioners were not persuaded of the wisdom of this course of action, and shied away from support for comprehensive judicial review as a protective lever. Their preference was for less intrusive mechanisms. At that stage of constitutional evolution, it seemed to them that adequate protection could be conferred on minority communities by the combination of two sets of safeguards. The first had to do with the numerical strength of minority representation in Parliament. The main plank of the submission in this regard by the Tamil-speaking leadership resided in a distinction between an absolute and a relative majority.

The gist of the argument was that the majority community, although admittedly in the legislature, should not be possessed of sufficient strength to override all minority representatives, taken together. With this end in view, Mr. G. G. Ponnambalam, leader of the All Ceylon Tamil Congress, argued strenuously for the 50-50 formula, in terms of which all minority communities collectively would be entitled to 50% representation, complemented by proportionate representation in the Cabinet of Ministers, as well. This was urged as the only realistic buffer against communal hegemony.

The extreme dimensions of this proposal held no appeal to the Soulbury Commissioners. Conceding as they did the gravity of the issue, they opted for a more moderate solution. This took the form of a proposed electoral system, at the base of which lay a mixture of population-based and territorial criteria. The basic character of the system involved the election of members relative to spread of population, subject however to the refinement that four additional members each were to be allocated to the Northern and Eastern Provinces, over and above their entitlement on the population-centric criteria.

The intention was to make provision in some form for “additional weightage in the interest of equity underpinning the electoral system, as a whole. This fell far short of the ambitious claim by the Tamil leadership for “balanced representation”, which entailed a mechanism to forestall a permanent Sinhala majority, with the probable risk of unbridled majoritarianism. The markedly limited scope of the suggested modality met with disillusionment on the part of the Tamil leadership. It was, nevertheless, not a stand-alone formula.

It stood in conjunction with a carefully crafted constitutional limitation on the legislative competence of Parliament. The legislature was expressly precluded from making any law, the effect of which was to “make persons of any community or religion liable to disabilities or restrictions to which persons of other made liable”, or “confer on persons of any community or religion any privilege or advantage which is not conferred on persons of other communities or religions”. Any law contravening this prohibition was characterized as void. The provision against discrimination, couched in this form, was susceptible to being overridden by a vote of two-thirds of the total membership of Parliament.

(To be continued next week)

(Excerpted from The Sri Lanka Peace Process: An Inside View by GL Peiris)

Features

Indo Pak’s Gamble on the New World Order

A few weeks after Pakistan’s nuclear-powered Prime Minister signed a defence pact with Saudi Arabia and secured arms agreements with Turkey, Qatar, Sudan, Indonesia, and Libya, India moved into the UAE and signed trade and defence agreements. Separately, it signed what it calls the “deal of the century” with the European Union, inviting Ursula von der Leyen as Chief Guest for its 77th Republic Day celebration. While Tejas crashed at the Dubai Expo last year, providing Pakistan critics with easy ridicule, India nonetheless advanced its agenda, signing multi-billion-dollar trade and defence agreements and preparing for a high-profile visit to Israel by Prime Minister Narendra Modi. While headlines paint these moves as strategic triumphs, beneath the surface lies a volatile struggle: two nuclear-armed neighbours attempting to draw their own Laksmana Rekha (the line drawn on the soil to protect Sita by Lashmana in the Ramayana) by for a new world order, risking chaos with consequences well beyond South Asia.

Pakistan’s deals in recent months are nothing short of audacious. The pact with Saudi Arabia explicitly treats any aggression against Pakistan as aggression against Riyadh, binding Islamabad to the security concerns of a regional power embroiled in a bitter rivalry with Iran. Pakistan’s agreements with Turkey, which include co-development of drones and armoured vehicles, as well as intelligence-sharing frameworks, suggest a regional mini-alliance designed to project influence far beyond its immediate borders. These moves are not defensive postures alone; they signal an intention to shape West Asia and Central Asia while balancing Indian ambitions. Adding to this, Pakistan inked a multibillion-dollar arms deal with Libya, which drew immediate attention when the Libyan army chief died in a conspicuous crash shortly thereafter. Pakistan also finalized a defence cooperation agreement with Sudan, signaling its intent to expand military partnerships in Africa and project influence beyond South Asia and West Asia. Whether coincidence or darker currents of geopolitics, the timing highlights the lethal stakes involved in defence diplomacy, where weaker states and volatile actors serve as instruments in larger strategic contests.

India, by contrast, is aggressively integrating economic and defence tools to extend influence across multiple fronts. The UAE deal combined free trade with advanced defence cooperation, including missile systems, surveillance drones, and joint training programmes. These agreements coincided with the symbolic elevation of European Union leaders to India’s Republic Day, signaling not only economic ambition but political legitimacy. The impending visit to Israel is expected to solidify long-term collaborations in drone technology, missile defence systems, and counter-terrorism platforms. India’s strategy is clear: to leverage defence-industrial partnerships to offset conventional gaps, acquire technological sophistication, and embed itself firmly in global strategic networks.

Yet India’s defence industry, despite international acclaim, is riddled with controversies exposing structural weaknesses and opacity. The Rafale deal remains contentious, with verified discrepancies in offset contracts and accusations of overpricing; the AgustaWestland VVIP helicopter deal saw politicians and intermediaries indicted for kickbacks; repeated accidents in indigenous platforms such as the Tejas fighter and MiG-21 fleet indicate systemic flaws in quality control, maintenance, and training. Reliance on foreign technology for critical components — GE engines for Tejas, Israeli avionics, and imported electronics for the Arjun tank — reveals the gap between the rhetoric of self-reliance and operational reality. The Indian Air Force and Army have acquired high-tech capabilities, but these exist alongside bureaucratic inefficiency, production delays, and safety failures, making the industrial base both a tool of power and a liability.

This collision of ambition and fragility is mirrored across the Indo-Pak divide. Pakistan’s pursuit of regional patrons for conventional security contrasts with India’s self-assertive, high-tech approach. Yet both are nuclear-armed, both are courting influential allies, and both are inserting themselves into conflicts far from their borders — in the Gulf, North Africa, and West Asia. These manoeuvres are not contained; they intensify tension. Saudi and Turkish influence over Pakistan ties its strategic calculus to Gulf rivalries, while India’s collaboration with Israel and the EU extends its reach into the Mediterranean and Europe. The potential for miscalculation is immense: one regional skirmish, one rogue actor, or one accident could ignite a chain reaction whose impact would extend beyond South Asia

India may think it can construct a permanent wall between itself and Pakistan — a physical barrier, a strategic fence, and a narrative of deterrence. But no concrete, defence pact, trade agreement, or alliance can contain the historical, ideological, and technological currents that run through this rivalry. Pakistan’s nuclear programme, developed clandestinely in response to India’s own atomic ambitions, compels Islamabad to seek external guarantees, ensuring that any confrontation is immediately linked to wider West Asian and Asian security dynamics. Similarly, India’s missile and drone partnerships are not mere instruments of sovereignty; they are nodes in a global network exposing New Delhi to the same pressures, particularly when public perception and operational realities collide, as the Tejas crash revealed.

The broader implication is that the Indo-Pak security theatre is no longer a bilateral problem; it is a crucible in which alliances, trade, and defence are interdependent. The UAE and Saudi rifts, the strategic entanglement of Turkey, the influence of Israel, and India’s engagement with the European Union and its new trade framework all contribute to a tense ecosystem. The Lakshmana Rekha that both states seek to draw is illusory: it pretends a clear separation between order and disorder, influence and vulnerability, when the reality is a network of fragile connections, asymmetrical dependencies, and high-stakes brinkmanship.

Worse, these developments are not purely defensive. Pakistan’s pacts suggest offensive potential in terms of drone deployment, missile sharing, and strategic depth across West Asia, while India’s high-tech collaboration signals readiness to project power, control information, and shape regional narratives. The risk is that these manoeuvres may yield short-term gains at the expense of systemic instability. Nuclear deterrence, advanced missiles, and sophisticated drones can either stabilize or provoke — depending on errors, miscalculations, or accidents. In a volatile region already characterized by insurgency, sectarian conflict, and rivalries, the consequences of failure would ripple across borders and oceans.

India and Pakistan are thus co-authors of a precarious new strategic architecture. One is anchored in Gulf patronage and regional alliances, the other in high-technology collaboration and ambitious economic defence diplomacy. Both are engaging history, ideology, and technological asymmetry, yet neither fully controls the external variables embedded in their strategies. The result is a fragile order, a geopolitical experiment whose failure could redraw regional maps, disrupt global trade, and trigger cascading insecurity. The lesson is stark: walls, deals, and pacts may signal ambition and project power, but they cannot contain volatility or replace strategic prudence.

No wonder India may imagine a permanent wall along the Indo-Pakistan border — physically, politically, and technologically — as if a line of concrete and agreements could partition history itself. The reality, however, is harsher, more complex, and potentially explosive. The Lakshmana Rekha these states are drawing is being etched through arms deals, alliances, nuclear posturing, and high-tech collaborations, yet the medium itself is unstable, prone to rupture, and capable of spilling disorder far beyond the subcontinent. The next world order they seek may never stabilize; it may simply be a prelude to a wider contest, with consequences that neither New Delhi nor Islamabad can fully control. In that sense, both nations are architects of their own audacious gamble, and the world watches — uneasily — to see whether this ambitious wall will hold, or crumble in flames reaching far beyond South Asia.

by Nilantha Ilangamuwa

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoComBank, UnionPay launch SplendorPlus Card for travelers to China

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoClimate risks, poverty, and recovery financing in focus at CEPA policy panel

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoSri Lanka, the Stars,and statesmen

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoHayleys Mobility ushering in a new era of premium sustainable mobility

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoLuck knocks at your door every day

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoAdvice Lab unveils new 13,000+ sqft office, marking major expansion in financial services BPO to Australia

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoArpico NextGen Mattress gains recognition for innovation

-

Editorial1 day ago

Editorial1 day agoGovt. provoking TUs