Features

POWER POLITICS

CHAPTER 14

(Excerpted from N.U. JAYAWARDENA The first five decades)

Continued From Last Week

It is said that Kotelawala made an application to the Central Bank for the transfer of a large sum of money to Britain for the purchase of property. NU mentioned that the application was made during the first premiership of Dudley Senanayake, “as financial protection from unsettling forces which he [Kotelawala] felt would overtake the country” (N.U. Jayawardena, c.1985, p.62). According to the Central Bank and Exchange Control regulations at that time, the transfer of such a large sum was not permissible, and would have violated existing regulations. As such, NU recommended the refusal of Kotelawala’s application to the Finance Minister J.R. Jayewardene and Prime Minister Dudley Senanayake. This action would have serious repercussions in the future. NU’s daughter describes this episode:

When my father was in the Central Bank, Sir John Kotelawala applied for special approval to remit funds to the United Kingdom, which exceeded the legally approved limit. My father in his tactless way said that he could not do this but that Sir John was welcome to change the law and that my father would grant him the required permit after this was done. My parents always maintained that Sir John Kotelawala never forgave my father for the stand he took on his request. (Neiliya Perera, personal recollections)

To shed some light on the reasons for NU’s stance on the issue, it is important to note that, while the “Rubber Boom” of 1950-51 (at the time of the Korean War) had permitted Sri Lanka to enjoy a brief spell of economic prosperity, due to an increase in the export price of rubber, by 1952 the Central Bank had warned the government about worsening economic conditions and began to re-impose “certain restrictions of [foreign] remittances” (Central Bank, c.1975, p.41). In mid-1952, the government also launched a programme that was “primarily designed to conserve foreign exchange and to eliminate the budget deficit” (ibid, p.49). However, in 1953, an adverse balance of trade still existed, leading to cash shortages, and the government had to obtain a sterling loan from the British government to bridge the gap. NU accompanied OEG, the Finance Minister, to Britain in 1953 to negotiate this loan, and did so again in 1954 to negotiate a further loan (Ranasinghe, 1972, p.306).

Kotelawala did not take kindly to NU’s rejection of his application to remit money abroad. According to Neiliya, NU was “a man who did not suffer fools gladly” and who was “outspoken to the point of being arrogant.” This rejection would have only rubbed further salt into the wounds of a powerful man who was quick to take insult. NU, with legendary abilities to master any subject and administrative skills valued by his superiors, would find that these assets did not serve him well in this case. He would soon learn that it was not wise to displease powerful politicians.

Some time during this period, a verbal skirmish of sorts had taken place between John Kotelawala and NU at the silver wedding reception of a mutual friend, with some name-calling, and Kotelawala threatened to take revenge on NU (Wickramaratne, 2002).

John Lionel Kotelawala

The above-described incidents as well as a few biographical details will provide some insight into the nature of the man who succeeded Dudley Senanayake as Prime Minister, and have relevance when describing the events that took place affecting NU. John Lionel Kotelawala, born in 1897 was the son of John Kotelawala, a police inspector, who after marriage became involved in the “management of his wife’s family estates and properties” (Wriggins, 1960, p.32). Kotelawala Sr. was celebrated in some quarters for his bravado and physical exploits. ( . See Dep, pp.317, 319 & 334; Jeffries, pp.29-30, K. Jayawardena, 1972, pp.125-27; and Kotelawala, pp.12-13 & 14. From the age of ten, Kotelawala Jr. was raised by his mother Alice, after his father died under unfortunate circumstances. (See: de Silva and Wriggins, 1988, p.46 and Wriggins, 1960, p.112.)

By his own account, Kotelawala (Jr.) (1956, p.12), was from his early days, impulsive – prone to “acting first and thinking afterwards” – and his memoirs are full of references to incidents in which he appears to extol the use of violence and strong-arm tactics. There are many anecdotes from his contemporaries and historians that attest to his volatile nature. (See Abeysekera, pp.145-46; Fernando, p.21; Jeffries pp.29-30; Kotelawala; pp.68-69, and Manor pp.192, 223-24 & 226.)

The Politics of Rice Subsidies

Events closely linked to the issue of food subsidies were to occur, which resulted in the decision by Dudley Senanayake to step down as Prime Minister and his replacement by Kotelawala. Food subsidies, which had been introduced during World War II as emergency measures to keep the cost of living down, had not been removed after the war and were regarded by the masses as an entrenched right However, food subsidies were becoming increasingly untenable, as the gap between the world price and the subsidized price of foodstuffs widened – as we have seen in Chapter 12. The opportunitycost of subsidizing food was the crowding out of expenditure on themuch-needed capital investment required to bring Sri Lanka out of its dependency on imports, which was the crux of the problem. In September 1952, the rice ration was reduced from two measures to one and the price of sugar was raised. Yet, by 1953, 20 per cent of the government revenue was being spent to meet the gap between the subsidized price of rice offered to the public and the actual price the government had to pay on the world market to obtain it (Wriggins, 1960, p.289).

Faced with an acute financial crisis, J.R. Jayewardene, as Finance Minister, proposed the withdrawal of the rice subsidy in the Budget of 1953/1954 – which meant that the price of rice would rise from 25 cents to 70 cents a measure. Aggravating the situation, the free midday meal for school children was also abolished, and the cost of rail travel and postal services was increased.

The Budget was passed in Parliament, but before the debate could be concluded, the Opposition seized this opportunity to organize a hartal (a stoppage of work and all activities) on 12 August 1953. All over the country, large crowds participated and blocked the roads in rural and urban areas. In order to disperse the crowds, the police opened fire, and some protesters were killed.

Unnerved by this event, Dudley Senanayake felt unable to cope with the turmoil and gave up his premiership, resulting in John Kotelawala taking office as Prime Minister in October 1953. J.R. Jayewardene was made Minister of Agriculture, and Oliver Goonetilleke became Finance Minister. Sometime after assuming office, Kotelawala lowered the price of subsidized rice to 55 cents, when a recovery in export prices made this possible. Nevertheless, the resentment of the public continued to grow. And though Kotelawala had finally achieved his ambition of becoming Prime Minister, his tenure in office would last barely two and a half years.

Upon Kotelawala’s assumption of office, the personal animosity between Kotelawala and NU appears to have continued unabated. According to Edmund Eramudugolla (2004, p.16), NU “took lightly” the official functions at Temple Trees (the Prime Minister’s residence) and “invariably arrived late… often just at the time [Kotelawala] was getting ready to leave for [his home in] Kandawala.” On one such occasion, as NU arrived, Kotelawala presented him to the other guests: “His Excellency the Governor of the Central Bank,

N.U. Jayawardena, a very busy man, busier than the PM.” NU did not seem to bow to those in power. As Eramudugolla observed, NU “was conscious of his intellectual brilliance but unfortunately built up an intellectual arrogance to the annoyance of important persons in the political and public life of the country” (ibid, p.18). In this atmosphere of political infighting, heightened emotions and intrigue, it did not take long for John Kotelawala to use his power to settle scores with NU.

Kotelawala’s Turbulent Term in Office

Kotelawala’s term in office was no easier than Dudley’s. Personal discord still existed within the party, while Kotelawala’s flamboyant lifestyle and public pronouncements stoked much controversy and anger among the public. In the course of his abbreviated premiership, both R.G. Senanayake and Dudley Senanayake would leave the party in an attempt to distance themselves from Kotelawala’s actions. While the UNP had many economic and social accomplishments of which it could be proud, resentment and outrage against what was seen as bribery and corruption within the government began to gain momentum. According to Wriggins (1960, p.335):

The wealth of the party, the privileged position of its known supporters… the alleged misuse of the public service and the fact that close relatives of the prime minister himself were appointed to lucrative and prominent posts regardless of competence did much to harm the U.N.P. In an apparent bid to deflect public fury away from the government, Kotelawala set up a Bribery Commission with special powers of investigation. It has been alleged that Kotelawala used the powers of this commission as an instrument to intimidate individuals and, as Wriggins (1960, p.335) stated, also for “personal revenge.”

Commission of Inquiry

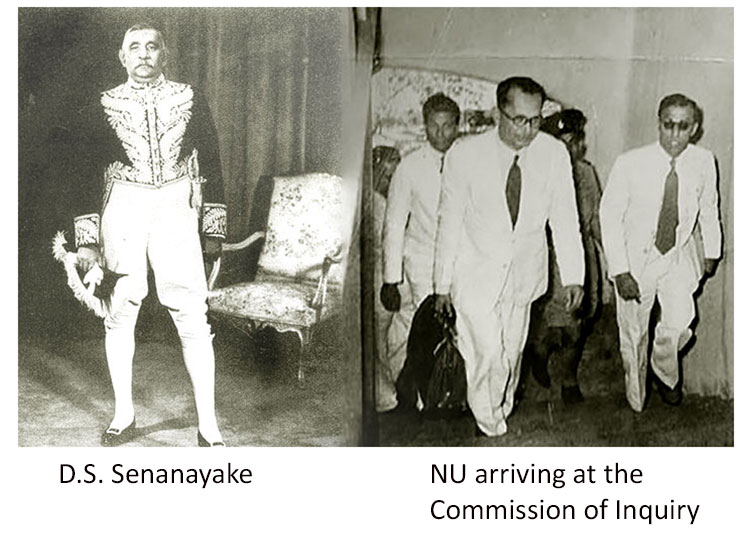

A few months after becoming Prime Minister, Kotelawala began his campaign against NU by appointing a commission to inquire into his conduct as Governor of the Central Bank. The commission consisted of Justice A.R.H. Canakaratne, Justice H. A. de Silva, and Sir Eric Jansz. It was given the following terms of inquiry: the affairs and general conduct of Neville Ubesinghe Jayawardena… and his wife Gertrude Mildred Jayawardena… and the financial and other dealings with banks, corporations and individuals of Mr. and Mrs. Jayawardena, before and after Mr. Jayawardena was appointed as Governor of the Central Bank and in particular upon forty-nine matters therein mentioned.

The Commission sat for 20 days. The lawyers for the Jayawardenas were D.S. Jayawickrema, Q.C., and G.T. Samarawickrema (NU’s maternal relation). The main charge was that NU, as Governor of the Central Bank, had taken loans for building his house from commercial banks and other sources. NU contended that, like any other citizen, he had the right to do so, and that this did not compromise his position as Governor of the Central Bank, nor jeopardize its interests. After the inquiry, the Commission gave its verdict that NU’s actions were violations of the position he held. The Commission reported that: While Mr. Jayawardena was holding the respective offices of Controller of Exchange, Deputy Governor and Governor of the Central Bank, the financial transactions of Mr. and Mrs. Jayawardena with their banks and other persons were on a scale quite out of proportion to their income. (p.72, No. 315 of Sessional Paper XX of 1954)

While holding high office, NU was alleged to have used his official position as security for loans from banks and individuals for the purchase of land. On the Commission’s verdict, NU was dismissed from the Central Bank on 15 October 1954. This blow could not have come at a worse time in his life. After serving the government for 28 years in various capacities and attending to problems that a lesser man could not have coped with, NU now found himself in the wilderness. His wife was suffering from a heart ailment, and he had two sons and a daughter to support. His elder son Lal was already studying for an Economics degree at Cambridge University, and the younger Nimal was soon to leave for Cambridge, to study Economics and Law. Concerned that his father could not meet the expenses, Nimal wanted to stay behind. However, NU assured him that he would somehow meet his expenses at Cambridge and urged him not to be hasty.

NU and his family, having had to move out of Bank House, had no place of their own to live. Until that time, they had lived in rented premises. Like most Sri Lankans, NU put great store in home ownership. Now, the house he had first owned in Park Road – built before he became Governor – had to be sold. As Neiliya recalls, the house:

was designed by Edward, Reid and Begg and built by the Tudawe Brothers. This house was rented out when we moved to the Bank Governor’s residence. Behind the house, he built two flats in the excess land, funded by the Colombo Commercial Company – which was to take on the premises on a rent-free basis for a number of years in return for the money the company invested. My parents had to sell the Park Road home, which they had so lovingly constructed, in order to pay for the case. My father and mother fortunately had the strength and courage to handle the situation.

The trauma took a toll on the family in other ways as well. Neiliya continues:

The period was extremely difficult for my parents and myself. My brothers were fortunately abroad in university and escaped most of the trauma. My parents suffered greatly as a result of this episode. My father, who was a very social person, became a recluse. He started writing articles on economics and banking and on a variety of subjects for the newspapers, to keep himself occupied.

After long being at the centre of a hectic social and working life, NU suddenly found himself relatively alone and isolated. However, during the crisis, he found out who his true friends were. According to Stanley Wickramaratne, some who had known him shunned him, while a few others came to his assistance. For instance, Clarence Amerasinghe, the owner of Car Mart, lent him a car, and some friends gave the family a place to stay. NU also received letters of support from friends around the world. They included persons high up in the banking sector in Britain, some of whom had known him officially. His friend Cyril Hawker, of the Bank of England, kept in touch with NU’s two sons, reporting back on their progress to their parents. In Sri Lanka, Peri Sunderam, an early mentor and former Minister of Labour who had given NU his first opportunities for advancement, and who greatly appreciated his ability, sent him a reassuring letter. He expressed his “deep regret,” and urged NU to have the “will of mind to face this calamity with courage and hope.” Knowing that NU would overcome this misfortune, Peri Sunderam wrote:

You are still young and your talents may be usefully employed for other service. I am sure that the future is not bleak for you and that your experience and ability will be harnessed. I hope that your children are clever enough not to be blasted by this temporary misfortune of yours. (Letter dated 15 Oct. 1954, N.U. Jayawardena Personal Files)

Chapter 13 can read online on – https://island.lk/the-central-bank-2/

By Kumari Jayawardena and Jennifer Moragoda ✍️

Features

Who Owns the Clock? The Quiet Politics of Time in Sri Lanka

(This is the 100th column of the Out of the Box series, which began on 6 September, 2023, at the invitation of this newspaper – Ed.)

A new year is an appropriate moment to pause, not for celebration, but to interrogate what our politics, policies, and public institutions have chosen to remember, forget, and repeat. We celebrate the dawn of another brand-new year. But whose calendar defines this moment?

We hang calendars on our walls and carry them in our phones, trusting them to keep our lives in order, meetings, exams, weddings, tax deadlines, pilgrimages. Yet calendars are anything but neutral. They are among humanity’s oldest instruments of power: tools that turn celestial rhythms into social rules and convert culture into governance. In Sri Lanka, where multiple traditions of time coexist, the calendar is not just a convenience, it is a contested terrain of identity, authority, and fairness.

Time is never just time

Every calendar expresses a political philosophy. Solar systems prioritise agricultural predictability and administrative stability; lunar systems preserve religious ritual even when seasons drift; lunisolar systems stitch both together, with intercalary months added to keep festivals in season while respecting the moon’s phases. Ancient India and China perfected this balancing act, proving that precision and meaning can coexist. Sri Lanka’s own rhythms, Vesak and Poson, Avurudu in April, Ramadan, Deepavali, sit inside this wider tradition.

What looks “technical” is actually social. A calendar decides when courts sit, when budgets reset, when harvests are planned, when children sit exams, when debts are due, and when communities celebrate. It says who gets to define “normal time,” and whose rhythms must adapt.

The colonial clock still ticks

Like many postcolonial societies, Sri Lanka inherited the Gregorian calendar as the default language of administration. January 1 is our “New Year” for financial statements, annual reports, contracts, fiscal plans, school terms, and parliamentary sittings, an imported date shaped by European liturgical cycles and temperate seasons rather than our monsoons or zodiac transitions. The lived heartbeat of the island, however, is Avurudu: tied to the sun’s movement into Mesha Rāshi, agricultural renewal, and shared rituals of restraint and generosity. The result is a quiet tension: the calendar of governance versus the calendar of lived culture.

This is not mere inconvenience; it is a subtle form of epistemic dominance. The administrative clock frames Gregorian time as “real,” while Sinhala, Tamil, and Islamic calendars are relegated to “cultural” exceptions. That framing shapes everything, from office leave norms to the pace at which development programmes expect communities to “comply”.

When calendars enforce authority

History reminds us that calendar reforms are rarely innocent. Julius Caesar’s reshaping of Rome’s calendar consolidated imperial power. Pope Gregory XIII’s reform aligned Christian ritual with solar accuracy while entrenching ecclesiastical authority. When Britain finally adopted the Gregorian system in 1752, the change erased 11 days and was imposed across its empire; colonial assemblies had little or no say. In that moment, time itself became a technology for governing distant subjects.

Sri Lanka knows this logic. The administrative layers built under colonial rule taught us to treat Gregorian dates as “official” and indigenous rhythms as “traditional.” Our contemporary fiscal deadlines, debt restructurings, even election cycles, now march to that imported drumbeat, often without asking how this timing sits with the island’s ecological and cultural cycles.

Development, deadlines and temporal violence

Modern governance is obsessed with deadlines: quarters, annual budgets, five-year plans, review missions. The assumption is that time is linear, uniform, and compressible. But a farmer in Anuradhapura and a rideshare driver in Colombo do not live in the same temporal reality. Monsoons, harvests, pilgrimage seasons, fasting cycles, school term transitions, these shape when people can comply with policy, pay taxes, attend trainings, or repay loans. When programmes ignore these rhythms, failure is framed as “noncompliance,” when in fact the calendar itself has misread society. This mismatch is a form of temporal violence: harm produced not by bad intentions, but by insensitive timing.

Consider microcredit repayment windows that peak during lean agricultural months, or school examinations scheduled without regard to Avurudu obligations. Disaster relief often runs on the donor’s quarterly clock rather than the community’s recovery pace. In each case, governance time disciplines lived time, and the least powerful bend the most.

Religious time vs administrative time

Sri Lanka’s plural religious landscape intensifies the calendar question. Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity relate to time differently: lunar cycles, solar markers, sacred anniversaries. The state acknowledges these mainly as public holidays, rather than integrating their deeper temporal logic into planning. Vesak is a day off, not a rhythm of reflection and restraint; Ramadan is accommodated as schedule disruption, not as a month that reorganises energy, sleep, and work patterns; Avurudu is celebrated culturally but remains administratively marginal. The hidden assumption is that “real work” happens on the Gregorian clock; culture is decorative. That assumption deserves challenge.

Sri Lanka’s plural religious landscape intensifies the calendar question. Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, and Christianity relate to time differently: lunar cycles, solar markers, sacred anniversaries. The state acknowledges these mainly as public holidays, rather than integrating their deeper temporal logic into planning. Vesak is a day off, not a rhythm of reflection and restraint; Ramadan is accommodated as schedule disruption, not as a month that reorganises energy, sleep, and work patterns; Avurudu is celebrated culturally but remains administratively marginal. The hidden assumption is that “real work” happens on the Gregorian clock; culture is decorative. That assumption deserves challenge.

The wisdom in complexity

Precolonial South and East Asian calendars were not confused compromises. They were sophisticated integrations of astronomy, agriculture, and ritual life, adding intercalary months precisely to keep festivals aligned with the seasons, and using lunar mansions (nakshatra) to mark auspicious thresholds. This plural logic admits that societies live on multiple cycles at once. Administrative convenience won with the Gregorian system, but at a cost: months that no longer relate to the moon (even though “month” comes from “moon”), and a yearstart with no intrinsic astronomical significance for our context.

Towards temporal pluralism

The solution is not to abandon the Gregorian calendar. Global coordination, trade, aviation, science, requires shared reference points. But ‘shared’ does not mean uncritical. Sri Lanka can lead by modelling temporal pluralism: a policy posture that recognises different ways of organising time as legitimate, and integrates them thoughtfully into governance.

Why timing is justice

In an age of economic adjustment and climate volatility, time becomes a question of justice: Whose rhythms does the state respect? Whose deadlines dominate? Whose festivals shape planning, and whose are treated as interruptions? The more governance assumes a single, imported tempo, the wider the gap between the citizens and the state. Conversely, when policy listens to local calendars, legitimacy grows, as does efficacy. People comply more when the schedule makes sense in their lives.

Reclaiming time without romanticism

This is not nostalgia. It is a pragmatic recognition that societies live on multiple cycles: ecological, economic, ritual, familial. Good policy stitches these cycles into a workable fabric. Poor policy flattens them into a grid and then blames citizens for falling through the squares.

Sri Lanka’s temporal landscape, Avurudu’s thresholds, lunar fasts, monsoon pulses, exam seasons, budget cycles, is rich, not chaotic. The task before us is translation: making administrative time converse respectfully with cultural time. We don’t need to slow down; we need to sync differently.

The last word

When British subjects woke to find 11 days erased in 1752, they learned that time could be rearranged by distant power. Our lesson, centuries later, is the opposite: time can be rearranged by near power, by a state that chooses to listen.

Calendars shape memory, expectation, discipline, and hope. If Sri Lanka can reimagine the governance of time, without abandoning global coordination, we might recover something profound: a calendar that measures not just hours but meaning. That would be a reform worthy of our island’s wisdom.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Medicinal drugs for Sri Lanka:The science of safety beyond rhetoric

The recent wave of pharmaceutical tragedies in Sri Lanka, as well as some others that have occurred regularly in the past, has exposed a terrifying reality: our medicine cabinets have become a frontline of risk and potential danger. In recent months, the silent sanctuary of Sri Lanka’s healthcare system has been shattered by a series of tragic, preventable deaths. The common denominator in these tragedies has been a failure in the most basic promise of medicine: that it will heal, not harm. This issue is entirely contrary to the immortal writings of the Father of Medicine, Hippocrates of the island of Kos, who wrote, “Primum non nocere,” which translates classically from Latin as “First do no harm.” The question of the safety of medicinal drugs is, at present, a real dilemma for those of us who, by virtue of our vocation, need to use them to help our patients.

For a nation that imports the vast majority of its medicinal drugs, largely from regional hubs like India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh, the promise of healing is only as strong as the laboratory that verifies these very same medicinal drugs. To prevent further problems, and even loss of lives, we must demand a world-class laboratory infrastructure that operates on science, not just sentiment. We desperately need a total overhaul of our pharmaceutical quality assurance architecture.

The detailed anatomy of a national drug testing facility is not merely a government office. It is a high-precision fortress. To meet international standards like ISO/IEC 17025 and World Health Organisation (WHO) Good Practices for Pharmaceutical Quality Control Laboratories, such a high-quality laboratory must be zoned into specialised units, each designed to catch a different type of failure.

* The Physicochemical Unit: This is where the chemical identity of a drug is confirmed. Using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS), scientists determine if a “500mg” tablet actually contains 500mg of the active ingredient or if it is filled with useless chalk.

* The Microbiology Suite: This is the most critical area for preventing “injection deaths.” It requires an ISO Class 5 Cleanroom: sterile environments where air is filtered to remove every microscopic particle. Here, technicians perform Sterility Testing to ensure no bacteria or fungi are present in medicines that have to be injected.

* The Instrumentation Wing: Modern testing requires Atomic Absorption Spectrometers to detect heavy metal contaminants (like lead or arsenic) and Stability Chambers to see how drugs react to Sri Lanka’s high humidity.

* The injectable drug contamination is a serious challenge. The most recent fatalities in our hospitals were linked to Intravenous (IV) preparations. When a drug is injected directly into the bloodstream, there is no margin for error. A proper national laboratory must conduct two non-negotiable tests:

* Bacterial Endotoxin Testing (BET): Even if a drug is “sterile” (all bacteria are dead), the dead bacteria leave behind toxic cell wall products called endotoxins. If injected, these residual compounds cause “Pyrogenic Reactions” with violent fevers, organ failure, and death. A functional lab must use the Limulus Amoebocyte Lysate (LAL) test to detect these toxins at the parts-per-billion level.

* Particulate Matter Analysis: Using laser obscuration, labs must verify that no microscopic shards of glass or plastic are floating in the vials. These can cause fatal blood clots or embolisms in the lungs.

It is absolutely vital to assess whether the medicine is available in the preparation in the prescribed amounts and whether it is active and is likely to work. This is Bioavailability. Sri Lanka’s heavy reliance on “generic” imports raises a critical question: Is the cheaper version from abroad as effective as the original, more expensive branded formulation? This is determined by Bioavailability (BA) and Bioequivalence (BE) studies.

A drug might have the right chemical formula, but if it does not dissolve properly in the stomach or reach the blood at the right speed, it is therapeutically useless. Bioavailability measures the rate and extent to which the active ingredient is absorbed into the bloodstream. If a cheaper generic drug is not “bioequivalent” to the original brand-named version, the patient is essentially taking a useless placebo. For patients with heart disease or epilepsy, even a 10% difference in bioavailability can lead to treatment failure. A proper national system must include a facility to conduct these studies, ensuring that every generic drug imported is a true “therapeutic equivalent” to the brand-named original.

As far as testing goes, the current testing philosophy is best described as Reactive, rather than Proactive. The current Sri Lankan system is “reactive”: we test a drug only after a patient has already suffered. This is a proven recipe for disaster. To protect the public, we must shift to a Proactive Surveillance Model of testing ALL drugs at many stages of their dispensing.

* Pre-Marketing Approval: No drug should reach a hospital shelf without “Batch Release” testing. Currently, we often accept the manufacturer’s own certificate of analysis, which is essentially like allowing students to grade their own examination answers.

* Random Post-Marketing Surveillance (PMS): Regulatory inspectors must have the power to walk into any rural pharmacy or state hospital, pick a box of medicine at random, and send it to the lab. This could even catch “substandard” drugs that may have degraded during shipping or storage in our tropical heat. PMS is the Final Safety Net. Even the best laboratories cannot catch every defect. Post-Marketing Surveillance is the ongoing monitoring of a drug’s safety after it has been released to the public. It clearly is the Gold Standard.

* Pharmacovigilance: A robust digital system where every “Adverse Drug Reaction” (ADR) is logged in a national database.

* Signal Detection: An example of this is if three hospitals in different provinces report a slight rash from the same batch of an antibiotic, the system should automatically “flag” that batch for immediate recall before a more severe, unfortunate event takes place.

* Testing for Contaminants: Beyond the active ingredients, we must test for excipient purity. In some global cases, cheaper “glycerin” used in syrups was contaminated with diethylene glycol, a deadly poison. A modern lab must have the technology to screen for these hidden killers.

When one considers the Human Element, Competence and Integrity, the very best equipment in the world is useless without the human capital to run it. A national lab would need the following:

* Highly Trained Pharmacologists and Microbiologists and all grades of staff who are compensated well enough to be immune to the “lobbying” of powerful external agencies.

* Digital Transparency: A database accessible to the public, where any citizen can enter a batch number from their medicine box and see the lab results.

Once a proper system is put in place, we need to assess as to how our facilities measure up against the WHO’s “Model Quality Assurance System.” That will ensure maintenance of internationally recognised standards. The confirmed unfavourable results of any testing procedure, if any, should lead to a very prompt “Blacklist” Initiative, which can be used to legally bar failing manufacturers from future tenders. Such an endeavour would help to keep all drug manufacturers and importers on their toes at all times.

This author believes that this article is based on the premise that the cost of silence by the medical profession would be catastrophic. Quality assurance of medicinal compounds is not an “extra” cost. It is a fundamental right of every Sri Lankan citizen, which is not at all subject to any kind of negotiation. Until our testing facilities match the sophistication of the manufacturers we buy from, we are not just importing medicine; we are importing potential risk.

The promises made by the powers-that-be to “update” the testing laboratories will remain as a rather familiar, unreliable, political theatre until we see a committed budget for mass spectrometry, cleanroom certifications, highly trained and committed staff and a fleet of independent inspectors. Quality control of therapeutic medicines is not a luxury; it is the price to be paid for a portal of entry into a civilised and intensively safe healthcare system. Every time we delay the construction of a comprehensive, proactive testing infrastructure, we are playing a game of Russian Roulette with the lives of our people.

The science is available, and the necessary technology exists. What is missing is the political will to put patient safety as the premier deciding criterion. The time for hollow rhetoric has passed, and the time for a scientifically fortified, transparent, and proactive regulatory mechanism is right now. The good health of all Sri Lankans, as well as even their lives, depend on it.

Dr B. J. C. Perera

Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Joint Editor, Sri Lanka Journal of Child Health

Section Editor, Ceylon Medical Journal

Features

Rebuilding Sri Lanka Through Inclusive Governance

In the immediate aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah, the government has moved swiftly to establish a Presidential Task Force for Rebuilding Sri Lanka with a core committee to assess requirements, set priorities, allocate resources and raise and disburse funds. Public reaction, however, has focused on the committee’s problematic composition. All eleven committee members are men, and all non-government seats are held by business personalities with no known expertise in complex national development projects, disaster management and addressing the needs of vulnerable populations. They belong to the top echelon of Sri Lanka’s private sector which has been making extraordinary profits. The government has been urged by civil society groups to reconsider the role and purpose of this task force and reconstitute it to be more representative of the country and its multiple needs.

The group of high-powered businessmen initially appointed might greatly help mobilise funds from corporates and international donors, but this group may be ill equipped to determine priorities and oversee disbursement and spending. It would be necessary to separate fundraising, fund oversight and spending prioritisation, given the different capabilities and considerations required for each. International experience in post disaster recovery shows that inclusive and representative structures are more likely to produce outcomes that are equitable, efficient and publicly accepted. Civil society, for instance, brings knowledge rooted in communities, experience in working with vulnerable groups and a capacity to question assumptions that may otherwise go unchallenged.

A positive and important development is that the government has been responsive to these criticisms and has invited at least one civil society representative to join the Rebuilding Sri Lanka committee. This decision deserves to be taken seriously and responded to positively by civil society which needs to call for more representation rather than a single representative. Such a demand would reflect an understanding that rebuilding after a national disaster cannot be undertaken by the state and the business community alone. The inclusion of civil society will strengthen transparency and public confidence, particularly at a moment when trust in institutions remains fragile. While one appointment does not in itself ensure inclusive governance, it opens the door to a more participatory approach that needs to be expanded and institutionalised.

Costly Exclusions

Going down the road of history, the absence of inclusion in government policymaking has cost the country dearly. The exclusion of others, not of one’s own community or political party, started at the very dawn of Independence in 1948. The Father of the Nation, D S Senanayake, led his government to exclude the Malaiyaha Tamil community by depriving them of their citizenship rights. Eight years later, in 1956, the Oxford educated S W R D Bandaranaike effectively excluded the Tamil speaking people from the government by making Sinhala the sole official language. These early decisions normalised exclusion as a tool of governance rather than accommodation and paved the way for seven decades of political conflict and three decades of internal war.

Exclusion has also taken place virulently on a political party basis. Both of Sri Lanka’s post Independence constitutions were decided on by the government alone. The opposition political parties voted against the new constitutions of 1972 and 1977 because they had been excluded from participating in their design. The proposals they had made were not accepted. The basic law of the country was never forged by consensus. This legacy continues to shape adversarial politics and institutional fragility. The exclusion of other communities and political parties from decision making has led to frequent reversals of government policy. Whether in education or economic regulation or foreign policy, what one government has done the successor government has undone.

Sri Lanka’s poor performance in securing the foreign investment necessary for rapid economic growth can be attributed to this factor in the main. Policy instability is not simply an economic problem but a political one rooted in narrow ownership of power. In 2022, when the people went on to the streets to protest against the government and caused it to fall, they demanded system change in which their primary focus was corruption, which had reached very high levels both literally and figuratively. The focus on corruption, as being done by the government at present, has two beneficial impacts for the government. The first is that it ensures that a minimum of resources will be wasted so that the maximum may be used for the people’s welfare.

Second Benefit

The second benefit is that by focusing on the crime of corruption, the government can disable many leaders in the opposition. The more opposition leaders who are behind bars on charges of corruption, the less competition the government faces. Yet these gains do not substitute for the deeper requirement of inclusive governance. The present government seems to have identified corruption as the problem it will emphasise. However, reducing or eliminating corruption by itself is not going to lead to rapid economic development. Corruption is not the sole reason for the absence of economic growth. The most important factor in rapid economic growth is to have government policies that are not reversed every time a new government comes to power.

For Sri Lanka to make the transition to self-sustaining and rapid economic development, it is necessary that the economic policies followed today are not reversed tomorrow. The best way to ensure continuity of policy is to be inclusive in governance. Instead of excluding those in the opposition, the mainstream opposition in particular needs to be included. In terms of system change, the government has scored high with regard to corruption. There is a general feeling that corruption in the country is much reduced compared to the past. However, with regard to inclusion the government needs to demonstrate more commitment. This was evident in the initial choice of cabinet ministers, who were nearly all men from the majority ethnic community. Important committees it formed, including the Presidential Task Force for a Clean Sri Lanka and the Rebuilding Sri Lanka Task Force, also failed at first to reflect the diversity of the country.

In a multi ethnic and multi religious society like Sri Lanka, inclusivity is not merely symbolic. It is essential for addressing diverse perspectives and fostering mutual understanding. It is important to have members of the Tamil, Muslim and other minority communities, and women who are 52 percent of the population, appointed to important decision making bodies, especially those tasked with national recovery. Without such representation, the risk is that the very communities most affected by the crisis will remain unheard, and old grievances will be reproduced in new forms. The invitation extended to civil society to participate in the Rebuilding Sri Lanka Task Force is an important beginning. Whether it becomes a turning point will depend on whether the government chooses to make inclusion a principle of governance rather than treat it as a show of concession made under pressure.

by Jehan Perera

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoChief selector’s remarks disappointing says Mickey Arthur

-

Opinion7 days ago

Opinion7 days agoDisasters do not destroy nations; the refusal to change does

-

Sports3 days ago

Sports3 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLankan aircrew fly daring UN Medevac in hostile conditions in Africa

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

News20 hours ago

News20 hours agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges