Features

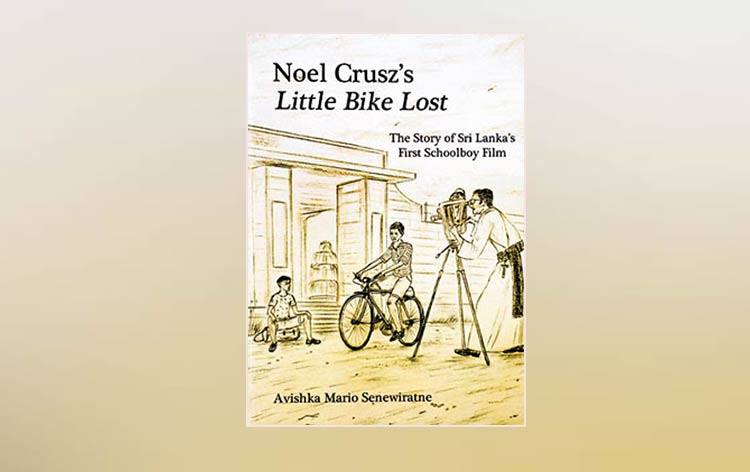

Noel Crusz’s Little Bike Lost: The Story of Sri Lanka’s First Schoolboy Film

by Rajiva Wijesinha

I had hugely enjoyed the Ceylon Journal, an exciting initiative from someone only recently out of school. Avishka Mario Senewiratne, who subsequently gave me one of his earlier books, which is an even more remarkable achievement. As the title indicates, it deals with a film made a long time ago.

He heard about it only when he was writing The Story of St. Joseph’s College, and promptly recognized it as ‘a phenomenal event that took place in 1956’. And this was not exaggeration, for the idea to make a film, and carry it through professionally, was unique, and Avishka is owed a debt of gratitude for having recorded the exercise so meticulously.

The film was the brainchild of Fr. Noel Crusz, whose name sounded familiar, for he had been known as an artist and also a priest who had later given up the priesthood, and married. Before that, he had while a teacher at St. Peter’s, been asked to produce ‘Catholic Hour’ for Radio Ceylon. And understanding his talent Cardinal Cooray, the head of the Catholic Church in Sri Lanka during my childhood, and for many years before that, sent him to Europe and America to study mass media.

He made many friends in Hollywood, who helped him in his film-making. Bing Crosby gave him the camera he used, and was later said to have helped with funding when he was running out, even after he had been given a loan of Rs.100 by the visionary educationist Fr. Peter Pillai.

When Vittorio De Sica’s ‘Bicycle Thieves’ reached cinemas in Colombo, Noel Crusz was at St. Josephs where he had set up a Film Society. One of its members, having slipped out to watch the film, and been caught and caned by Peter Pillai who was then the Rector, thought up a script which appealed to Crusz. This was good timing, for 1955/56 had been declared the Diamond Jubilee year of SJC. Before that Crusz had written and produced plays, and also made documentary films. A feature was a new departure that he thought appropriate for the Jubilee, but while he remained in charge he gave the boys of the Film Society full responsibility, and they lived up to this admirably.

Avishka has given full details of the process, with chapters about the selection of the cast and crew, the different locations used, and what took place behind the scenes, followed by a short account of how the footage was put together. In between, which shows admirable pacing on the writer’s part, is a long chapter detailing the plot of the film. Then we have the press preview and the reactions, which were almost entirely positive. Even Mervyn de Silva, though less enthusiastic, registered the great initiative displayed, and praised the young people ‘in a society that is well known for its timidity’.

But then tragedy strikes. For Kingsley De Rosairo, the boy who had organized the fighting and the race sequences, inspired by the subject of the film, persuaded his father to buy him a new bicycle. His cousin was given one too, and the two raced round Colombo, and even cycled one day to Avissawella and back. But then one evening, the evening of the press preview, when they got home, they found that their music teacher had come and gone and left a message that they should come to his home. So Kingley set off, and was knocked down by a passing truck, when he had almost reached the house. And though he was rushed to hospital, doctors could do nothing and he died next morning, without regaining consciousness.

But the show went on. The one strong criticism made of the film was that the sound was messy, for it had had to be dubbed as the camera used did not allow for the recording of speech. And since the cast read out what they were supposed to say, it had sounded stilted. Crusz then accepted the suggestion that this be dropped, and managed to have the new version, without any conversation, ready for the Gala Premiere which took place at the Lionel Wendt.

The Prime Minister Mr Bandaranaike graced the occasion, with his wife and daughter who were both elected to that position in time, and made a very complimentary speech. And before the screening Mrs Bandaranaike gave out awards to the cast and crew. The main star of the film got an Olympic New Yorker bicycle, the same as he had won in a raffle in the film and then had it stolen from him, before recovering it and winning the Cycle Race at the Sports Meet.

He was tongue-tied when Chandrika asked him how he had done his role, and the producer had to answer for him. But after that little touch, Avishka ends the chapter with him cycling home on his new bike. And even more moving had been the earlier record of Charmaine De Rozairo going on stage ‘to collect a prize on behalf of her later younger brother, Kingsley’.

He was tongue-tied when Chandrika asked him how he had done his role, and the producer had to answer for him. But after that little touch, Avishka ends the chapter with him cycling home on his new bike. And even more moving had been the earlier record of Charmaine De Rozairo going on stage ‘to collect a prize on behalf of her later younger brother, Kingsley’.

But after that there were no more films. After his account of the Gala Premiere, Avishka records the popularity of the film all over the country, with screenings in several other venues including Jaffna. But then, typically, though Fr. Crusz now had many fans, his work upset some of his superiors, and early in 1958 he was transferred, whereupon the Film Society died away. The writer of this film had written another screenplay called ‘Shanty Dwellers’, but it did not see the light of day.

Avishka does not expand on the reasons for the transfer, simply noting in the last chapter that Crusz served in Kohuwala and Jaffna and Maggona, before giving up the priesthood in 1965. He had also given up his role on ‘Catholic Hour’, though why this should have happened while he was in Kohuwala is not clear. I suspect rather that the conservative elements in the Church asserted themselves, not at all happy with Crusz’s strong sense of social justice – as exemplified indeed by the subject of the proposed second film.

For Crusz was associated with the radical Peter Pillai and also it would seem with the future liberation theologian Tissa Balasuriya, who was also then on the SJC staff and who was later excommunicated. By then Crusz had left the country, and lived out his life in Australia, where he finally wrote a book about the Cocos Island Mutiny, the only instance in the Second World War when soldiers were executed for mutiny. They were Ceylonese and his longstanding concern with the story makes it clear that his thirst for social justice had not diminished.

But the last chapter also has heartwarming accounts of what happened to the boys over the years, including the surprise party the producers of the film threw for Noel Crusz for his 95th birthday. They managed to trace the hero, Gerry D’Silva, whose unexpected presence drove Crusz to tears of joy. Earlier we were told about how he was reunited with the second lead, Bryan Walles, who had migrated to America, after his mother saw an article Crusz wrote in 1995 about the making of the film.

Sadly hardly any of the cast and crew remained in Sri Lanka. Many were Burgher and departed in the sad exodus of this talented group in the sixties and seventies. But even the Sinhalese producer Lalin Fernando went, though one important member of the production team, Ranjith Pereira, stayed behind and had a distinguished career in the country.

If the last chapter has a valedictory air, the penultimate one recreates the sense of adventure that Crusz had encouraged, for it is about how Bryan Walles and three of his friends, carried away by Tarzan books, decided to leave Colombo and live in the jungles of Madhu. So they set off by train, but at Maradana one of the boys decided to stay behind.

Unfortunately for the rest, he revealed the plan to his parents so the boys found the police waiting for them on the platform at Polgahawela, and they were taken home. But the chapter ends with a picture of Bryan on an elephant, finally pulling off a Tarzan, around 30 years later.

That picture is one of the splendid illustrations with which the book abounds. It contrasts, as do the many pictures in the last chapter, with the pictures of the boys in school, including several stills taken while the film was being made. The pictures exude innocence, though the book, and the film, are full of the fights which seem to have been a staple of existence in the school in those days.

The pictures also capture the questioning look the heroes, the boy who lost his bike and his younger brother, seem to have displayed in life as in the film. The four bullies, on the other hand, look tough, at all times, though the one who double-crossed the others and told Tommy where the bike was also has a wary look in his portrait picture.

The girls, whom Noel Crusz chose from Holy Family Convent, where he had previously produced plays, are striking, though Tommy’s older sisters are suitably admonitory in the stills. Sadly the older sister – which they were in real life too – died in the first decade of this century but the younger one, who looks radiant in the picture of her with her husband in Australia, was still living when the book was written.

Then there are the picture of the places where filming took place, including an array of pictures of St. Joseph’s as it was 70 years ago. And there are crowd shots, not only of the cycle race, but even of one of Sri Lanka’s greatest sportmen, Nagalingam Ethirveerasingham, about to leap high at the sports meet. Supplementing these are a few imaginative sketches which bring alive the personalities of not only Noel Crusz but also Peter Pillai and the Vice-Rector, to say nothing of Bing Crosby.

The book ends with three appendices, the last the filmography of Crusz, while the first tells the tale of the inspiration for the film, Vittorio De Sica’s ‘Bicycle Thieves’. The second appendix is a fascinating letter from Crusz written almost half a century after the film was made, about the process of creating a soundtrack through dubbing that was more professional than the first effort, and which included the crowd voices used then.

I thought the book a triumph for many reasons. First in that it recreated a singular achievement of a school 70 years ago, while conveying the enthusiasm and the dedication of schoolboys of that period. Second it records the tremendous achievement of Noel Crusz, while also registering the sadness of his career being spiked as it were by unsympathetic authority.

Third it brings together heaps of period pictures, supplemented by pictures of youngsters grown old, which is a healthy reminder of the passing of time, while the buildings of St. Joseph’s, though altered over the years, mark the continuity of a distinguished heritage. To add another perspective, the writer has collected advertisements of those days for both cameras and bicycles, that record too the impact the film made – as do the newspaper cuttings about the triumph as well as the tragedy of Kenneth De Rozairo’s death.

In a bleak world it has been heartening to see the initiatives and the dedication of Avishka Mario Senewiratne, first with regard to the inspired Ceylon Journal and now this revival of a forgotten story and singular achievement. And his ability to recreate the past reminds me of something my former Dean once wrote, that ‘The past envelopes you like a warm blanket.’

Features

Theocratic Iran facing unprecedented challenge

The world is having the evidence of its eyes all over again that ‘economics drives politics’ and this time around the proof is coming from theocratic Iran. Iranians in their tens of thousands are on the country’s streets calling for a regime change right now but it is all too plain that the wellsprings of the unprecedented revolt against the state are economic in nature. It is widespread financial hardship and currency depreciation, for example, that triggered the uprising in the first place.

The world is having the evidence of its eyes all over again that ‘economics drives politics’ and this time around the proof is coming from theocratic Iran. Iranians in their tens of thousands are on the country’s streets calling for a regime change right now but it is all too plain that the wellsprings of the unprecedented revolt against the state are economic in nature. It is widespread financial hardship and currency depreciation, for example, that triggered the uprising in the first place.

However, there is no denying that Iran’s current movement for drastic political change has within its fold multiple other forces, besides the economically affected, that are urging a comprehensive transformation as it were of the country’s political system to enable the equitable empowerment of the people. For example, the call has been gaining ground with increasing intensity over the weeks that the country’s number one theocratic ruler, President Ali Khamenei, steps down from power.

That is, the validity and continuation of theocratic rule is coming to be questioned unprecedentedly and with increasing audibility and boldness by the public. Besides, there is apparently fierce opposition to the concentration of political power at the pinnacle of the Iranian power structure.

Popular revolts have been breaking out every now and then of course in Iran over the years, but the current protest is remarkable for its social diversity and the numbers it has been attracting over the past few weeks. It could be described as a popular revolt in the genuine sense of the phrase. Not to be also forgotten is the number of casualties claimed by the unrest, which stands at some 2000.

Of considerable note is the fact that many Iranian youths have been killed in the revolt. It points to the fact that youth disaffection against the state has been on the rise as well and could be at boiling point. From the viewpoint of future democratic development in Iran, this trend needs to be seen as positive.

Politically-conscious youngsters prioritize self-expression among other fundamental human rights and stifling their channels of self-expression, for example, by shutting down Internet communication links, would be tantamount to suppressing youth aspirations with a heavy hand. It should come as no surprise that they are protesting strongly against the state as well.

Another notable phenomenon is the increasing disaffection among sections of Iran’s women. They too are on the streets in defiance of the authorities. A turning point in this regard was the death of Mahsa Amini in 2022, which apparently befell her all because she defied state orders to be dressed in the Hijab. On that occasion as well, the event brought protesters in considerable numbers onto the streets of Tehran and other cities.

Once again, from the viewpoint of democratic development the increasing participation of Iranian women in popular revolts should be considered thought-provoking. It points to a heightening political consciousness among Iranian women which may not be easy to suppress going forward. It could also mean that paternalism and its related practices and social forms may need to re-assessed by the authorities.

It is entirely a matter for the Iranian people to address the above questions, the neglect of which could prove counter-productive for them, but it is all too clear that a relaxing of authoritarian control over the state and society would win favour among a considerable section of the populace.

However, it is far too early to conclude that Iran is at risk of imploding. This should be seen as quite a distance away in consideration of the fact that the Iranian government is continuing to possess its coercive power. Unless the country’s law enforcement authorities turn against the state as well this coercive capability will remain with Iran’s theocratic rulers and the latter will be in a position to quash popular revolts and continue in power. But the ruling authorities could not afford the luxury of presuming that all will be well at home, going into the future.

Meanwhile US President Donald Trump has assured the Iranian people of his assistance but it is not clear as to what form such support would take and when it would be delivered. The most important way in which the Trump administration could help the Iranian people is by helping in the process of empowering them equitably and this could be primarily achieved only by democratizing the Iranian state.

It is difficult to see the US doing this to even a minor measure under President Trump. This is because the latter’s principal preoccupation is to make the ‘US Great Once again’, and little else. To achieve the latter, the US will be doing battle with its international rivals to climb to the pinnacle of the international political system as the unchallengeable principal power in every conceivable respect.

That is, Realpolitik considerations would be the main ‘stuff and substance’ of US foreign policy with a corresponding downplaying of things that matter for a major democratic power, including the promotion of worldwide democratic development and the rendering of humanitarian assistance where it is most needed. The US’ increasing disengagement from UN development agencies alone proves the latter.

Given the above foreign policy proclivities it is highly unlikely that the Iranian people would be assisted in any substantive way by the Trump administration. On the other hand, the possibility of US military strikes on Iranian military targets in the days ahead cannot be ruled out.

The latter interventions would be seen as necessary by the US to keep the Middle Eastern military balance in favour of Israel. Consequently, any US-initiated peace moves in the real sense of the phrase in the Middle East would need to be ruled out in the foreseeable future. In other words, Middle East peace will remain elusive.

Interestingly, the leadership moves the Trump administration is hoping to make in Venezuela, post-Maduro, reflect glaringly on its foreign policy preoccupations. Apparently, Trump will be preferring to ‘work with’ Delcy Rodriguez, acting President of Venezuela, rather than Maria Corina Machado, the principal opponent of Nicolas Maduro, who helped sustain the opposition to Maduro in the lead-up to the latter’s ouster and clearly the democratic candidate for the position of Venezuelan President.

The latter development could be considered a downgrading of the democratic process and a virtual ‘slap in its face’. While the democratic rights of the Venezuelan people will go disregarded by the US, a comparative ‘strong woman’ will receive the Trump administration’s blessings. She will perhaps be groomed by Trump to protect the US’s security and economic interests in South America, while his administration side-steps the promotion of the democratic empowerment of Venezuelans.

Features

Silk City: A blueprint for municipal-led economic transformation in Sri Lanka

Maharagama today stands at a crossroads. With the emergence of new political leadership, growing public expectations, and the convergence of professional goodwill, the Maharagama Municipal Council (MMC) has been presented with a rare opportunity to redefine the city’s future. At the heart of this moment lies the Silk City (Seda Nagaraya) Initiative (SNI)—a bold yet pragmatic development blueprint designed to transform Maharagama into a modern, vibrant, and economically dynamic urban hub.

This is not merely another urban development proposal. Silk City is a strategic springboard—a comprehensive economic and cultural vision that seeks to reposition Maharagama as Sri Lanka’s foremost textile-driven commercial city, while enhancing livability, employment, and urban dignity for its residents. The Silk City concept represents more than a development plan: it is a comprehensive economic blueprint designed to redefine Maharagama as Sri Lanka’s foremost textile-driven commercial and cultural hub.

A Vision Rooted in Reality

What makes the Silk City Initiative stand apart is its grounding in economic realism. Carefully designed around the geographical, commercial, and social realities of Maharagama, the concept builds on the city’s long-established strengths—particularly its dominance as a textile and retail centre—while addressing modern urban challenges.

The timing could not be more critical. With Mayor Saman Samarakoon assuming leadership at a moment of heightened political goodwill and public anticipation, MMC is uniquely positioned to embark on a transformation of unprecedented scale. Leadership, legitimacy, and opportunity have aligned—a combination that cities rarely experience.

A Voluntary Gift of National Value

In an exceptional and commendable development, the Maharagama Municipal Council has received—entirely free of charge—a comprehensive development proposal titled “Silk City – Seda Nagaraya.” Authored by Deshamanya, Deshashkthi J. M. C. Jayasekera, a distinguished Chartered Accountant and Chairman of the JMC Management Institute, the proposal reflects meticulous research, professional depth, and long-term strategic thinking.

It must be added here that this silk city project has received the political blessings of the Parliamentarians who represented the Maharagama electorate. They are none other than Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports and Youth Affairs, Sunil Watagala, Deputy Minister of Public Security and Devananda Suraweera, Member of Parliament.

The blueprint outlines ten integrated sectoral projects, including : A modern city vision, Tourism and cultural city development, Clean and green city initiatives, Religious and ethical city concepts, Garden city aesthetics, Public safety and beautification, Textile and creative industries as the economic core

Together, these elements form a five-year transformation agenda, capable of elevating Maharagama into a model municipal economy and a 24-hour urban hub within the Colombo Metropolitan Region

Why Maharagama, Why Now?

Maharagama’s transformation is not an abstract ambition—it is a logical evolution. Strategically located and commercially vibrant, the city already attracts thousands of shoppers daily. With structured investment, branding, and infrastructure support, Maharagama can evolve into a sleepless commercial destination, a cultural and tourism node, and a magnet for both local and international consumers.

Such a transformation aligns seamlessly with modern urban development models promoted by international development agencies—models that prioritise productivity, employment creation, poverty reduction, and improved quality of life.

Rationale for Transformation

Maharagama has long held a strategic advantage as one of Sri Lanka’s textile and retail centers. With proper planning and investment, this identity can be leveraged to convert the city into a branded urban destination, a sleepless commercial hub, a tourism and cultural attraction, and a vibrant economic engine within the Colombo Metropolitan Region. Such transformation is consistent with modern city development models promoted by international funding agencies that seek to raise local productivity, employment, quality of life, alleviation of urban poverty, attraction and retaining a huge customer base both local and international to the city)

Current Opportunity

The convergence of the following factors make this moment and climate especially critical. Among them the new political leadership with strong public support, availability of a professionally developed concept paper, growing public demand for modernisation, interest among public, private, business community and civil society leaders to contribute, possibility of leveraging traditional strengths (textile industry and commercial vibrancy are notable strengths.

The Silk City initiative therefore represents a timely and strategic window for Maharagama to secure national attention, donor interest and investor confidence.

A Window That Must Not Be Missed

Several factors make this moment decisive: Strong new political leadership with public mandate, Availability of a professionally developed concept, Rising citizen demand for modernization, Willingness of professionals, businesses, and civil society to contribute. The city’s established textile and commercial base

Taken together, these conditions create a strategic window to attract national attention, donor interest, and investor confidence.

But windows close.

Hard Truths: Challenges That Must Be Addressed

Ambition alone will not deliver transformation. The Silk City Initiative demands honest recognition of institutional constraints. MMC currently faces: Limited technical and project management capacity, rigid public-sector regulatory frameworks that slow procurement and partnerships, severe financial limitations, with internal revenues insufficient even for routine operations, the absence of a fully formalised, high-caliber Steering Committee.

Moreover, this is a mega urban project, requiring feasibility studies, impact assessments, bankable proposals, international partnerships, and sustained political and community backing.

A Strategic Roadmap for Leadership

For Mayor Saman Samarakoon, this represents a once-in-a-generation leadership moment. Key strategic actions are essential: 1.Immediate establishment of a credible Steering Committee, drawing expertise from government, private sector, academia, and civil society. 2. Creation of a dedicated Project Management Unit (PMU) with professional specialists. 3. Aggressive mobilisation of external funding, including central government support, international donors, bilateral partners, development banks, and corporate CSR initiatives. 4. Strategic political engagement to secure legitimacy and national backing. 5. Quick-win projects to build public confidence and momentum. 6. A structured communications strategy to brand and promote Silk City nationally and internationally. Firm positioning of textiles and creative industries as the heart of Maharagama’s economic identity

If successfully implemented, Silk City will not only redefine Maharagama’s future but also ensure that the names of those who led this transformation are etched permanently in the civic history of the city.

Voluntary Gift of National Value

Maharagama is intrinsically intertwined with the textile industry. Small scale and domestic textile industry play a pivotal role. Textile industry generates a couple of billion of rupees to the Maharagama City per annum. It is the one and only city that has a sleepless night and this textile hub provides ready-made garments to the entire country. Prices are comparatively cheaper. If this textile industry can be vertically and horizontally developed, a substantial income can be generated thus providing employment to vulnerable segments of employees who are mostly women. Paucity of textile technology and capital investment impede the growth of the industry. If Maharagama can collaborate with the Bombay of India textile industry, there would be an unbelievable transition. How Sri Lanka could pursue this goal. A blueprint for the development of the textile industry for the Maharagama City will be dealt with in a separate article due to time space.

It is achievable if the right structures, leadership commitments and partnerships are put in place without delay.

No municipal council in recent memory has been presented with such a pragmatic, forward-thinking and well-timed proposal. Likewise, few Mayors will ever be positioned as you are today — with the ability to initiate a transformation that will redefine the future of Maharagama for generations. It will not be a difficult task for Saman Samarakoon, Mayor of the MMC to accomplish the onerous tasks contained in the projects, with the acumen and experience he gained from his illustrious as a Commander of the SL Navy with the support of the councilors, Municipal staff and the members of the Parliamentarians and the committed team of the Silk-City Project.

Voluntary Gift of National Value

Maharagama is intrinsically intertwined with the textile industry. The textile industries play a pivotal role. This textile hub provides ready-made garments to the entire country. Prices are comparatively cheaper. If this textile industry can be vertically and horizontally developed, a substantial income can be generated thus providing employment to vulnerable segments of employees who are mostly women.

Paucity of textile technology and capital investment impede the growth of the industry. If Maharagama can collaborate with the Bombay of India textile industry, there would be an unbelievable transition. A blueprint for the development of the textile industry for the Maharagama City will be dealt with in a separate article.

J.A.A.S Ranasinghe

Productivity Specialist and Management Consultant

(The writer can becontacted via Email:rathula49@gmail.com)

Features

Reading our unfinished economic story through Bandula Gunawardena’s ‘IMF Prakeerna Visadum’

Book Review

Why Sri Lanka’s Return to the IMF Demands Deeper Reflection

By mid-2022, the term “economic crisis” ceased to be an abstract concept for most Sri Lankans. It was no longer confined to academic papers, policy briefings, or statistical tables. Instead, it became a lived and deeply personal experience. Fuel queues stretched for kilometres under the burning sun. Cooking gas vanished from household shelves. Essential medicines became difficult—sometimes impossible—to find. Food prices rose relentlessly, pushing basic nutrition beyond the reach of many families, while real incomes steadily eroded.

What had long existed as graphs, ratios, and warning signals in economic reports suddenly entered daily life with unforgiving force. The crisis was no longer something discussed on television panels or debated in Parliament; it was something felt at the kitchen table, at the bus stop, and in hospital corridors.

Amid this social and economic turmoil came another announcement—less dramatic in appearance, but far more consequential in its implications. Sri Lanka would once again seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The announcement immediately divided public opinion. For some, the IMF represented an unavoidable lifeline—a last resort to stabilise a collapsing economy. For others, it symbolised a loss of economic sovereignty and a painful surrender to external control. Emotions ran high. Debates became polarised. Public discourse quickly hardened into slogans, accusations, and ideological posturing.

Yet beneath the noise, anger, and fear lay a more fundamental question—one that demanded calm reflection rather than emotional reaction:

Why did Sri Lanka have to return to the IMF at all?

This question does not lend itself to simple or comforting answers. It cannot be explained by a single policy mistake, a single government, or a single external shock. Instead, it requires an honest examination of decades of economic decision-making, institutional weaknesses, policy inconsistency, and political avoidance. It requires looking beyond the immediate crisis and asking how Sri Lanka repeatedly reached a point where IMF assistance became the only viable option.

Few recent works attempt this difficult task as seriously and thoughtfully as Dr. Bandula Gunawardena’s IMF Prakeerna Visadum. Rather than offering slogans or seeking easy culprits, the book situates Sri Lanka’s IMF engagement within a broader historical and structural narrative. In doing so, it shifts the debate away from blame and toward understanding—a necessary first step if the country is to ensure that this crisis does not become yet another chapter in a familiar and painful cycle.

Returning to the IMF: Accident or Inevitability?

The central argument of IMF Prakeerna Visadum is at once simple and deeply unsettling. It challenges a comforting narrative that has gained popularity in times of crisis and replaces it with a far more demanding truth:

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis was not created by the IMF.

IMF intervention became inevitable because Sri Lanka avoided structural reform for far too long.

This framing fundamentally alters the terms of the national debate. It shifts attention away from external blame and towards internal responsibility. Instead of asking whether the IMF is good or bad, Dr. Gunawardena asks a more difficult and more important question: what kind of economy repeatedly drives itself to a point where IMF assistance becomes unavoidable?

The book refuses the two easy positions that dominate public discussion. It neither defends the IMF uncritically as a benevolent saviour nor demonises it as the architect of Sri Lanka’s suffering. Instead, IMF intervention is placed within a broader historical and structural context—one shaped primarily by domestic policy choices, institutional weaknesses, and political avoidance.

Public discourse often portrays IMF programmes as the starting point of economic hardship. Dr. Gunawardena corrects this misconception by restoring the correct chronology—an essential step for any honest assessment of the crisis.

The IMF did not arrive at the beginning of Sri Lanka’s collapse.

It arrived after the collapse had already begun.

By the time negotiations commenced, Sri Lanka had exhausted its foreign exchange reserves, lost access to international capital markets, officially defaulted on its external debt, and entered a phase of runaway inflation and acute shortages.

Fuel queues, shortages of essential medicines, and scarcities of basic food items were not the product of IMF conditionality. They were the direct outcome of prolonged foreign-exchange depletion combined with years of policy mismanagement. Import restrictions were imposed not because the IMF demanded them, but because the country simply could not pay its bills.

From this perspective, the IMF programme did not introduce austerity into a functioning economy. It formalised an adjustment that had already become unavoidable. The economy was already contracting, consumption was already constrained, and living standards were already falling. The IMF framework sought to impose order, sequencing, and credibility on a collapse that was already under way.

Seen through this lens, the return to the IMF was not a freely chosen policy option, but the end result of years of postponed decisions and missed opportunities.

A Long IMF Relationship, Short National Memory

Sri Lanka’s engagement with the IMF is neither new nor exceptional. For decades, governments of all political persuasions have turned to the Fund whenever balance-of-payments pressures became acute. Each engagement was presented as a temporary rescue—an extraordinary response to an unusual storm.

Yet, as Dr. Gunawardena meticulously documents, the storms were not unusual. What was striking was not the frequency of crises, but the remarkable consistency of their underlying causes.

Fiscal indiscipline persisted even during periods of growth. Government revenue remained structurally weak. Public debt expanded rapidly, often financing recurrent expenditure rather than productive investment. Meanwhile, the external sector failed to generate sufficient foreign exchange to sustain a consumption-led growth model.

IMF programmes brought temporary stability. Inflation eased. Reserves stabilised. Growth resumed. But once external pressure diminished, reform momentum faded. Political priorities shifted. Structural weaknesses quietly re-emerged.

This recurring pattern—crisis, adjustment, partial compliance, and relapse—became a defining feature of Sri Lanka’s economic management. The most recent crisis differed only in scale. This time, there was no room left to postpone adjustment.

Fiscal Fragility: The Core of the Crisis

A central focus of IMF Prakeerna Visadum is Sri Lanka’s chronically weak fiscal structure. Despite relatively strong social indicators and a capable administrative state, government revenue as a share of GDP remained exceptionally low.

Frequent tax changes, politically motivated exemptions, and weak enforcement steadily eroded the tax base. Instead of building a stable revenue system, governments relied increasingly on borrowing—both domestic and external.

Much of this borrowing financed subsidies, transfers, and public sector wages rather than productivity-enhancing investment. Over time, debt servicing crowded out development spending, shrinking fiscal space.

Fiscal reform failed not because it was technically impossible, Dr. Gunawardena argues, but because it was politically inconvenient. The costs were immediate and visible; the benefits long-term and diffuse. The eventual debt default was therefore not a surprise, but a delayed consequence.

The External Sector Trap

Sri Lanka’s narrow export base—apparel, tea, tourism, and remittances—generated foreign exchange but masked deeper weaknesses. Export diversification stagnated. Industrial upgrading lagged. Integration into global value chains remained limited.

Meanwhile, import-intensive consumption expanded. When external shocks arrived—global crises, pandemics, commodity price spikes—the economy had little resilience.

Exchange-rate flexibility alone cannot generate exports. Trade liberalisation without an industrial strategy redistributes pain rather than creates growth.

Monetary Policy and the Cost of Lost Credibility

Prolonged monetary accommodation, often driven by political pressure, fuelled inflation, depleted reserves, and eroded confidence. Once credibility was lost, restoring it required painful adjustment.

Macroeconomic credibility, Dr. Gunawardena reminds us, is a national asset. Once squandered, it is extraordinarily expensive to rebuild.

IMF Conditionality: Stabilisation Without Development?

IMF programmes stabilise economies, but they do not automatically deliver inclusive growth. In Sri Lanka, adjustment raised living costs and reduced real incomes. Social safety nets expanded, but gaps persisted.

This raises a critical question: can stabilisation succeed politically if it fails socially?

Political Economy: The Missing Middle

Reforms collided repeatedly with electoral incentives and patronage networks. IMF programmes exposed contradictions but could not resolve them. Without domestic ownership, reform risks becoming compliance rather than transformation.

Beyond Blame: A Diagnostic Moment

The book’s greatest strength lies in its refusal to engage in blame politics. IMF intervention is treated as a diagnostic signal, not a cause—a warning light illuminating unresolved structural failures.

The real challenge is not exiting an IMF programme, but exiting the cycle that makes IMF programmes inevitable.

A Strong Public Appeal: Why This Book Must Be Read

This is not an anti-IMF book.

It is not a pro-IMF book.

It is a pro-Sri Lanka book.

Published by Sarasaviya Publishers, IMF Prakeerna Visadum equips readers not with anger, but with clarity—offering history, evidence, and honest reflection when the country needs them most.

Conclusion: Will We Learn This Time?

The IMF can stabilise an economy.

It cannot build institutions.

It cannot create competitiveness.

It cannot deliver inclusive development.

Those responsibilities remain domestic.

The question before Sri Lanka is simple but profound:

Will we repeat the cycle, or finally learn the lesson?

The answer does not lie in Washington.

It lies with us.

By Professor Ranjith Bandara

Emeritus Professor, University of Colombo

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNew policy framework for stock market deposits seen as a boon for companies

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II

-

News4 days ago

News4 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament