Features

National Defence College of Sri Lanka

I was invited to deliver a lecture at the Diners Club of the National Defence College (NDC), the highest Defence learning establishment of Sri Lanka, by its Commandant, Major General Amal Karunasekara, highly decorated officer from the Sri Lanka Light Infantry. Our inaugural NDC course started on 14 November, 2021, and 14 senior officers from the Army, seven from the Navy, six from the Air Force and four from the Police took part in the one-year-long course.

I was very happy about the invitation, as the Chief of Defence Staff, in 2017 to 2019, I was involved in securing this mansion, known as ‘Mumtaz Mahal,’ Colombo 03 the former official residence of the Speaker of Parliament, from 1948 to 2000, until a new official residence for the Speaker was built, close to the Parliament. From year 2000, this mansion, located on a land extending up to the Marine Drive, from the Galle Road, had been neglected, and when the Defence Ministry acquired it for establishing the NDC, it was badly in need of repairs. Further, the once beautiful garden had been used as a junk yard of the Presidential Secretariet, which owns the property.

It was great an achievement by the Defence Secretary and the CDS, at that time (2016), to secure this invaluable property, in the heart of Colombo’s residential area, especially when all three services were losing their prime land, in Colombo, and moving out of Colombo, to Akuregoda, including their Headquarters.

The task of repairing the building, and to bring it back to the previous glory, was vasted upon the Navy Civil Engineering Department and they did a wonderful job, in spite of the work getting delayed, due to lack of funds. The Air Force took the responsibility of landscaping.

‘Mumtaz Mahal’ was built by Mr Mohomad Hussain, well known businessman, in 1928. He commissioned well known architect, at that time, Homi Billimoria, who designed the Colombo Town Hall. This was an Italian design house where Count de Mauny was commissioned to the design garden and furniture.

On a suggestion made by Hubert Sri Nissanka,QC ( a founding member of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party), a close friend of Mr Hussain, the mansion was named, under the name of his youngest daughter Mumtaz. History says the overseas business of Mr Hussain was badly affected, during the Great Depression, and he hired the mansion to the French government, in 1943, and the French Consul occupied it till the start of the Second World War. During War, the mansion was sold to the government and, in 1943, the Governor General of Ceylon at that time, Vice Admiral Godfrey Layton, Commander-in-Chief, occupied it as his residence, fearing that the Japanese may bomb the Governor General House, in Fort.

During interactions with our new President, at Security Council meetings, when he was PM and I was CDS, he mentioned some of these historical details ,and the War Cabinet, during World War Two, under Vice Admiral Layton, has met in this Mansion, in the room which is the present day auditorium.

My lecture heading was Sri Lanka and Indo-Pacific Maritime Strategies and extracts from the lecture are given below.

The former U.S. Indo-Pacific Commander, Admiral Harry Harris, delivering his keynote speech at the Galle Dialogue 2016, attributed Sri Lanka’s strategic importance to the US on three factors; “Location, location and location”.

Book cover by Shivshankar Menon

These words by Admiral Harris amply highlight the geopolitical importance of Sri Lanka in the Indo-Pacific region and in the global context. Former Indian National Security Adviser (NSA) and Foreign Secretary, Shiv Shankar Menon, in his book Choices, described Sri Lanka as a permanent aircraft carrier for India, in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Though this claim could politically be contentious, it transpires a geopolitical reality of the region. It is no secret that other global powers, like China and Russia, also look at Sri Lanka through a similar geopolitical lens. On the other hand, this island nation is also located amidst major sea routes in the world; just a few miles South of the Dondra head lighthouse, over 120 ships pass daily, carrying goods upon which the health of global markets depend.

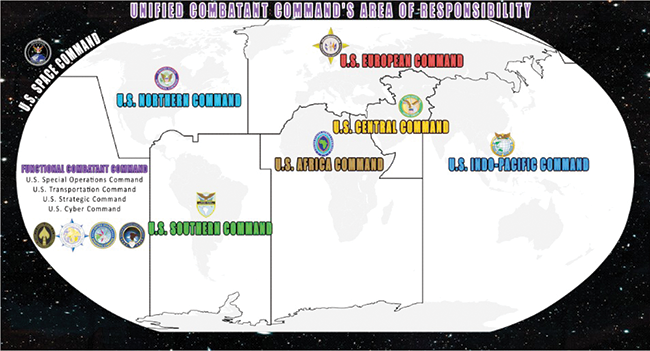

US Commands

In this context, it is essential for Sri Lanka to hold a pragmatic policy on strategic defence diplomacy engagements with regional and global superpowers while ensuring its sovereignty and integrity is preserved all the while respecting the national foreign policy stance of remaining non-aligned and neutral. Thus, defence diplomacy should be a considerable concern of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy.

What is Defence Diplomacy? It refers to the pursuit of foreign policy objectives through the peaceful deployment of defence resources and capabilities.

In the post-Cold War period, western defence establishments, led by the UK, created a new international security arrangement, focused on defence diplomacy. Although it originated many centuries, before the world wars, defence diplomacy is now used successfully by both the global West and the developing South to further national strategic and security interests.

The work of defence diplomacy is not limited to ‘track-one diplomacy’ (official government-led diplomacy) engagements such as defence / military attaches/ advisors at diplomatic missions abroad. Engagements, such as personnel exchanges, bilateral meetings, staff talks, training, exercises (air, land and naval), regional defence forums and ships / aircraft visits are also key in fostering track-II diplomatic engagements to bolster defence diplomacy.

Some experts note these extended engagements can be considered one of the best strategies in regional and global conflict prevention, since these interactions would enhance understanding, while diluting misconceptions between nation states.

Sri Lanka’s position at the centre of the Indian Ocean makes it an important maritime hub. The island nation’s deepwater harbours, relatively peaceful environment and the democratic governing system, have been the main attractions for many countries with strategic interests in the Indian Ocean.

Empty oil tankers sail from the East to the West to replenish, while the products from Japan, China and South Korea sail to Europe, the Gulf and Indian markets, through the major maritime routes across which Sri Lanka falls, thrusting this island nation into the heart of the global economy. But the importance of the location is not limited to economic gains; the strategic significance of Sri Lanka’s ports, due to their access to some of the key regions of the world, has garnered the attention of the world.

The popular belief is that China may soon become the most powerful global superpower. But I argue otherwise mainly due to four main factors.

·USA is still the global economic giant; its GDP still exceeds that of China by a marked difference

=The USA still dominates in terms of global military strength ranking – China comes in third

=The USA is the only country that has actively engaged in strategic areas of the six regions in the world, with its Army, Navy, Airforce and Marines deployed in all these six regions. No other country has that capability of already deployed combating forces.

=The US Navy has 11 aircraft carriers for its power projection out of the world’s 43 active aircraft carriers, but China has only two in active service while a third is being manufactured. Therefore, China has a long way to go to become a global superpower even mainly from the defence perspective.

But, one could easily argue on the fact that China is also fast aspiring to become a global superpower through a different strategy. Its overseas investments, mainly on constructions of harbors and ports as well as also ship/submarine building programs are impressive new tactics in achieving maritime prowess mainly in the southern hemisphere of the globe. Being a heavy dependant on energy supply from the Gulf to keep its economy afloat, China has two strategies in dominating the Indian Ocean, which has now become its lifeline.

The first is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) announced by Chinese President Xi Jinping in September 2013 while speaking to the Indonesian Parliament. The BRI has now become China’s ambitious foreign policy objective for the 21st century. It’s a vision encompasses over 60 countries with a combined population of over four billion people throughout Asia, Central Asia, Indian Ocean Littoral and Europe. Sri Lanka is a major stakeholder in this BRI initiative.

China’s second strategy is not announced by China but remains a geographical hypothesis projected by the US and other western researchers in 2004 – the ‘String of Pearls’. The term refers to the network of Chinese military and commercial maritime facilities (harbors and ports) along its sea lines of communication, which extends from mainland China to the port of Sudan in the Horn of Africa. The US and Indian strategists claim that the Colombo and Hambantota harbours where Chinese presence and investments are highly visible are major parts of this strategy. Of course, China denies this hypothesis and claims that those engagements are mere investments through bilateral arrangements and insists they have nothing to do with its military interests. Nevertheless, we noticed a concerning narrative even in Sri Lanka with regard to the Chinese military presence at Hambantota port during its initial stage which was vehemently denied by both governments of Sri Lanka and China.

In this context, one can notice several defence and maritime alliances are emerging in a bid to contain China, mainly due to its aforesaid two-pronged developments. One such regional collaborative defence response is the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (QUAD) – a strategic dialogue between the United States, India, Japan and Australia. The leaders of these four nations met for the first time in Washington DC in September 2021. Among these four players, Australia has adopted a much more aggressive posture, a few weeks ago in signing the AUKUS (Australia, UK and US) pact, which allows Australia to develop nuclear submarines. Though it is not publicly announced, it is clear this move is to operate in the Indian Ocean against the Chinese presence. However, this AUKUS deal did not go well due to objections from many traditional allies like France and NATO.

On the other hand, the US, Japan and India have separate collective Indo- Pacific strategies to respond to China. , outlines a strategic plan for the country’s defence interests and has awarded a special place to Sri Lanka. Accordingly, a Defence Adviser to the Australian High Commission in Colombo was appointed three years ago. It shows that our Defence diplomacy with Australia is also becoming a higher priority in our bilateral diplomatic agenda.

In this context, balancing the existing supremacy of the US and the emerging powers such as China mainly through defence diplomacy has become one of the most important aspects of Sri Lanka’s foreign policy. We may learn from Singapore, which presently serves as a logistics hub for all US Navy ships. Providing logistic support to warship visits is also a very lucrative business. It is noteworthy to mention the fact that security and stability of a country is extremely important for foreign warship visits.

Another concerning factor is the influence by our neighbor India, which does not want Sri Lanka to become a playground for its rival superpowers. Furthermore, Colombo harbour is an extremely important venue to India where 60 percent of its containerized cargo transshipments are handled. Last week, we showed the World that even the largest container-carrying ship in the world can enter and load/unload at Colombo harbour, showing promise and capacity as one of the most important ports in the world.

The most important aim of India’s foreign policy is to become a permanent member at the UN Security Council. Indian Foreign policy is said to be influenced by the teachings of Kautilya’s Arthashasthra – a statecraft treatise written by the ancient Indian philosopher and royal advisor to Emperor Chandraguptha Maurya in the 4th Century BCE.

Under whatever circumstances, Sri Lanka should be cautious to ensure that its actions do not jeopardize the security interests of India. The closest neighbor is the most important player even in our domestic lives and that argument is even greatly applicable in a country’s foreign policy formation. Next door neighbor is the fastest respondent when you are in danger or in crisis than allies thousand kilometers away and recent incidents such as the Xpress Pearl disaster have taught us that. Therefore, it may be a lesson well-remembered by Sri Lanka in deploying its foreign policy and defense diplomacy strategies in the age of the Indo-Pacific.

Features

Theocratic Iran facing unprecedented challenge

The world is having the evidence of its eyes all over again that ‘economics drives politics’ and this time around the proof is coming from theocratic Iran. Iranians in their tens of thousands are on the country’s streets calling for a regime change right now but it is all too plain that the wellsprings of the unprecedented revolt against the state are economic in nature. It is widespread financial hardship and currency depreciation, for example, that triggered the uprising in the first place.

The world is having the evidence of its eyes all over again that ‘economics drives politics’ and this time around the proof is coming from theocratic Iran. Iranians in their tens of thousands are on the country’s streets calling for a regime change right now but it is all too plain that the wellsprings of the unprecedented revolt against the state are economic in nature. It is widespread financial hardship and currency depreciation, for example, that triggered the uprising in the first place.

However, there is no denying that Iran’s current movement for drastic political change has within its fold multiple other forces, besides the economically affected, that are urging a comprehensive transformation as it were of the country’s political system to enable the equitable empowerment of the people. For example, the call has been gaining ground with increasing intensity over the weeks that the country’s number one theocratic ruler, President Ali Khamenei, steps down from power.

That is, the validity and continuation of theocratic rule is coming to be questioned unprecedentedly and with increasing audibility and boldness by the public. Besides, there is apparently fierce opposition to the concentration of political power at the pinnacle of the Iranian power structure.

Popular revolts have been breaking out every now and then of course in Iran over the years, but the current protest is remarkable for its social diversity and the numbers it has been attracting over the past few weeks. It could be described as a popular revolt in the genuine sense of the phrase. Not to be also forgotten is the number of casualties claimed by the unrest, which stands at some 2000.

Of considerable note is the fact that many Iranian youths have been killed in the revolt. It points to the fact that youth disaffection against the state has been on the rise as well and could be at boiling point. From the viewpoint of future democratic development in Iran, this trend needs to be seen as positive.

Politically-conscious youngsters prioritize self-expression among other fundamental human rights and stifling their channels of self-expression, for example, by shutting down Internet communication links, would be tantamount to suppressing youth aspirations with a heavy hand. It should come as no surprise that they are protesting strongly against the state as well.

Another notable phenomenon is the increasing disaffection among sections of Iran’s women. They too are on the streets in defiance of the authorities. A turning point in this regard was the death of Mahsa Amini in 2022, which apparently befell her all because she defied state orders to be dressed in the Hijab. On that occasion as well, the event brought protesters in considerable numbers onto the streets of Tehran and other cities.

Once again, from the viewpoint of democratic development the increasing participation of Iranian women in popular revolts should be considered thought-provoking. It points to a heightening political consciousness among Iranian women which may not be easy to suppress going forward. It could also mean that paternalism and its related practices and social forms may need to re-assessed by the authorities.

It is entirely a matter for the Iranian people to address the above questions, the neglect of which could prove counter-productive for them, but it is all too clear that a relaxing of authoritarian control over the state and society would win favour among a considerable section of the populace.

However, it is far too early to conclude that Iran is at risk of imploding. This should be seen as quite a distance away in consideration of the fact that the Iranian government is continuing to possess its coercive power. Unless the country’s law enforcement authorities turn against the state as well this coercive capability will remain with Iran’s theocratic rulers and the latter will be in a position to quash popular revolts and continue in power. But the ruling authorities could not afford the luxury of presuming that all will be well at home, going into the future.

Meanwhile US President Donald Trump has assured the Iranian people of his assistance but it is not clear as to what form such support would take and when it would be delivered. The most important way in which the Trump administration could help the Iranian people is by helping in the process of empowering them equitably and this could be primarily achieved only by democratizing the Iranian state.

It is difficult to see the US doing this to even a minor measure under President Trump. This is because the latter’s principal preoccupation is to make the ‘US Great Once again’, and little else. To achieve the latter, the US will be doing battle with its international rivals to climb to the pinnacle of the international political system as the unchallengeable principal power in every conceivable respect.

That is, Realpolitik considerations would be the main ‘stuff and substance’ of US foreign policy with a corresponding downplaying of things that matter for a major democratic power, including the promotion of worldwide democratic development and the rendering of humanitarian assistance where it is most needed. The US’ increasing disengagement from UN development agencies alone proves the latter.

Given the above foreign policy proclivities it is highly unlikely that the Iranian people would be assisted in any substantive way by the Trump administration. On the other hand, the possibility of US military strikes on Iranian military targets in the days ahead cannot be ruled out.

The latter interventions would be seen as necessary by the US to keep the Middle Eastern military balance in favour of Israel. Consequently, any US-initiated peace moves in the real sense of the phrase in the Middle East would need to be ruled out in the foreseeable future. In other words, Middle East peace will remain elusive.

Interestingly, the leadership moves the Trump administration is hoping to make in Venezuela, post-Maduro, reflect glaringly on its foreign policy preoccupations. Apparently, Trump will be preferring to ‘work with’ Delcy Rodriguez, acting President of Venezuela, rather than Maria Corina Machado, the principal opponent of Nicolas Maduro, who helped sustain the opposition to Maduro in the lead-up to the latter’s ouster and clearly the democratic candidate for the position of Venezuelan President.

The latter development could be considered a downgrading of the democratic process and a virtual ‘slap in its face’. While the democratic rights of the Venezuelan people will go disregarded by the US, a comparative ‘strong woman’ will receive the Trump administration’s blessings. She will perhaps be groomed by Trump to protect the US’s security and economic interests in South America, while his administration side-steps the promotion of the democratic empowerment of Venezuelans.

Features

Silk City: A blueprint for municipal-led economic transformation in Sri Lanka

Maharagama today stands at a crossroads. With the emergence of new political leadership, growing public expectations, and the convergence of professional goodwill, the Maharagama Municipal Council (MMC) has been presented with a rare opportunity to redefine the city’s future. At the heart of this moment lies the Silk City (Seda Nagaraya) Initiative (SNI)—a bold yet pragmatic development blueprint designed to transform Maharagama into a modern, vibrant, and economically dynamic urban hub.

This is not merely another urban development proposal. Silk City is a strategic springboard—a comprehensive economic and cultural vision that seeks to reposition Maharagama as Sri Lanka’s foremost textile-driven commercial city, while enhancing livability, employment, and urban dignity for its residents. The Silk City concept represents more than a development plan: it is a comprehensive economic blueprint designed to redefine Maharagama as Sri Lanka’s foremost textile-driven commercial and cultural hub.

A Vision Rooted in Reality

What makes the Silk City Initiative stand apart is its grounding in economic realism. Carefully designed around the geographical, commercial, and social realities of Maharagama, the concept builds on the city’s long-established strengths—particularly its dominance as a textile and retail centre—while addressing modern urban challenges.

The timing could not be more critical. With Mayor Saman Samarakoon assuming leadership at a moment of heightened political goodwill and public anticipation, MMC is uniquely positioned to embark on a transformation of unprecedented scale. Leadership, legitimacy, and opportunity have aligned—a combination that cities rarely experience.

A Voluntary Gift of National Value

In an exceptional and commendable development, the Maharagama Municipal Council has received—entirely free of charge—a comprehensive development proposal titled “Silk City – Seda Nagaraya.” Authored by Deshamanya, Deshashkthi J. M. C. Jayasekera, a distinguished Chartered Accountant and Chairman of the JMC Management Institute, the proposal reflects meticulous research, professional depth, and long-term strategic thinking.

It must be added here that this silk city project has received the political blessings of the Parliamentarians who represented the Maharagama electorate. They are none other than Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports and Youth Affairs, Sunil Watagala, Deputy Minister of Public Security and Devananda Suraweera, Member of Parliament.

The blueprint outlines ten integrated sectoral projects, including : A modern city vision, Tourism and cultural city development, Clean and green city initiatives, Religious and ethical city concepts, Garden city aesthetics, Public safety and beautification, Textile and creative industries as the economic core

Together, these elements form a five-year transformation agenda, capable of elevating Maharagama into a model municipal economy and a 24-hour urban hub within the Colombo Metropolitan Region

Why Maharagama, Why Now?

Maharagama’s transformation is not an abstract ambition—it is a logical evolution. Strategically located and commercially vibrant, the city already attracts thousands of shoppers daily. With structured investment, branding, and infrastructure support, Maharagama can evolve into a sleepless commercial destination, a cultural and tourism node, and a magnet for both local and international consumers.

Such a transformation aligns seamlessly with modern urban development models promoted by international development agencies—models that prioritise productivity, employment creation, poverty reduction, and improved quality of life.

Rationale for Transformation

Maharagama has long held a strategic advantage as one of Sri Lanka’s textile and retail centers. With proper planning and investment, this identity can be leveraged to convert the city into a branded urban destination, a sleepless commercial hub, a tourism and cultural attraction, and a vibrant economic engine within the Colombo Metropolitan Region. Such transformation is consistent with modern city development models promoted by international funding agencies that seek to raise local productivity, employment, quality of life, alleviation of urban poverty, attraction and retaining a huge customer base both local and international to the city)

Current Opportunity

The convergence of the following factors make this moment and climate especially critical. Among them the new political leadership with strong public support, availability of a professionally developed concept paper, growing public demand for modernisation, interest among public, private, business community and civil society leaders to contribute, possibility of leveraging traditional strengths (textile industry and commercial vibrancy are notable strengths.

The Silk City initiative therefore represents a timely and strategic window for Maharagama to secure national attention, donor interest and investor confidence.

A Window That Must Not Be Missed

Several factors make this moment decisive: Strong new political leadership with public mandate, Availability of a professionally developed concept, Rising citizen demand for modernization, Willingness of professionals, businesses, and civil society to contribute. The city’s established textile and commercial base

Taken together, these conditions create a strategic window to attract national attention, donor interest, and investor confidence.

But windows close.

Hard Truths: Challenges That Must Be Addressed

Ambition alone will not deliver transformation. The Silk City Initiative demands honest recognition of institutional constraints. MMC currently faces: Limited technical and project management capacity, rigid public-sector regulatory frameworks that slow procurement and partnerships, severe financial limitations, with internal revenues insufficient even for routine operations, the absence of a fully formalised, high-caliber Steering Committee.

Moreover, this is a mega urban project, requiring feasibility studies, impact assessments, bankable proposals, international partnerships, and sustained political and community backing.

A Strategic Roadmap for Leadership

For Mayor Saman Samarakoon, this represents a once-in-a-generation leadership moment. Key strategic actions are essential: 1.Immediate establishment of a credible Steering Committee, drawing expertise from government, private sector, academia, and civil society. 2. Creation of a dedicated Project Management Unit (PMU) with professional specialists. 3. Aggressive mobilisation of external funding, including central government support, international donors, bilateral partners, development banks, and corporate CSR initiatives. 4. Strategic political engagement to secure legitimacy and national backing. 5. Quick-win projects to build public confidence and momentum. 6. A structured communications strategy to brand and promote Silk City nationally and internationally. Firm positioning of textiles and creative industries as the heart of Maharagama’s economic identity

If successfully implemented, Silk City will not only redefine Maharagama’s future but also ensure that the names of those who led this transformation are etched permanently in the civic history of the city.

Voluntary Gift of National Value

Maharagama is intrinsically intertwined with the textile industry. Small scale and domestic textile industry play a pivotal role. Textile industry generates a couple of billion of rupees to the Maharagama City per annum. It is the one and only city that has a sleepless night and this textile hub provides ready-made garments to the entire country. Prices are comparatively cheaper. If this textile industry can be vertically and horizontally developed, a substantial income can be generated thus providing employment to vulnerable segments of employees who are mostly women. Paucity of textile technology and capital investment impede the growth of the industry. If Maharagama can collaborate with the Bombay of India textile industry, there would be an unbelievable transition. How Sri Lanka could pursue this goal. A blueprint for the development of the textile industry for the Maharagama City will be dealt with in a separate article due to time space.

It is achievable if the right structures, leadership commitments and partnerships are put in place without delay.

No municipal council in recent memory has been presented with such a pragmatic, forward-thinking and well-timed proposal. Likewise, few Mayors will ever be positioned as you are today — with the ability to initiate a transformation that will redefine the future of Maharagama for generations. It will not be a difficult task for Saman Samarakoon, Mayor of the MMC to accomplish the onerous tasks contained in the projects, with the acumen and experience he gained from his illustrious as a Commander of the SL Navy with the support of the councilors, Municipal staff and the members of the Parliamentarians and the committed team of the Silk-City Project.

Voluntary Gift of National Value

Maharagama is intrinsically intertwined with the textile industry. The textile industries play a pivotal role. This textile hub provides ready-made garments to the entire country. Prices are comparatively cheaper. If this textile industry can be vertically and horizontally developed, a substantial income can be generated thus providing employment to vulnerable segments of employees who are mostly women.

Paucity of textile technology and capital investment impede the growth of the industry. If Maharagama can collaborate with the Bombay of India textile industry, there would be an unbelievable transition. A blueprint for the development of the textile industry for the Maharagama City will be dealt with in a separate article.

J.A.A.S Ranasinghe

Productivity Specialist and Management Consultant

(The writer can becontacted via Email:rathula49@gmail.com)

Features

Reading our unfinished economic story through Bandula Gunawardena’s ‘IMF Prakeerna Visadum’

Book Review

Why Sri Lanka’s Return to the IMF Demands Deeper Reflection

By mid-2022, the term “economic crisis” ceased to be an abstract concept for most Sri Lankans. It was no longer confined to academic papers, policy briefings, or statistical tables. Instead, it became a lived and deeply personal experience. Fuel queues stretched for kilometres under the burning sun. Cooking gas vanished from household shelves. Essential medicines became difficult—sometimes impossible—to find. Food prices rose relentlessly, pushing basic nutrition beyond the reach of many families, while real incomes steadily eroded.

What had long existed as graphs, ratios, and warning signals in economic reports suddenly entered daily life with unforgiving force. The crisis was no longer something discussed on television panels or debated in Parliament; it was something felt at the kitchen table, at the bus stop, and in hospital corridors.

Amid this social and economic turmoil came another announcement—less dramatic in appearance, but far more consequential in its implications. Sri Lanka would once again seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The announcement immediately divided public opinion. For some, the IMF represented an unavoidable lifeline—a last resort to stabilise a collapsing economy. For others, it symbolised a loss of economic sovereignty and a painful surrender to external control. Emotions ran high. Debates became polarised. Public discourse quickly hardened into slogans, accusations, and ideological posturing.

Yet beneath the noise, anger, and fear lay a more fundamental question—one that demanded calm reflection rather than emotional reaction:

Why did Sri Lanka have to return to the IMF at all?

This question does not lend itself to simple or comforting answers. It cannot be explained by a single policy mistake, a single government, or a single external shock. Instead, it requires an honest examination of decades of economic decision-making, institutional weaknesses, policy inconsistency, and political avoidance. It requires looking beyond the immediate crisis and asking how Sri Lanka repeatedly reached a point where IMF assistance became the only viable option.

Few recent works attempt this difficult task as seriously and thoughtfully as Dr. Bandula Gunawardena’s IMF Prakeerna Visadum. Rather than offering slogans or seeking easy culprits, the book situates Sri Lanka’s IMF engagement within a broader historical and structural narrative. In doing so, it shifts the debate away from blame and toward understanding—a necessary first step if the country is to ensure that this crisis does not become yet another chapter in a familiar and painful cycle.

Returning to the IMF: Accident or Inevitability?

The central argument of IMF Prakeerna Visadum is at once simple and deeply unsettling. It challenges a comforting narrative that has gained popularity in times of crisis and replaces it with a far more demanding truth:

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis was not created by the IMF.

IMF intervention became inevitable because Sri Lanka avoided structural reform for far too long.

This framing fundamentally alters the terms of the national debate. It shifts attention away from external blame and towards internal responsibility. Instead of asking whether the IMF is good or bad, Dr. Gunawardena asks a more difficult and more important question: what kind of economy repeatedly drives itself to a point where IMF assistance becomes unavoidable?

The book refuses the two easy positions that dominate public discussion. It neither defends the IMF uncritically as a benevolent saviour nor demonises it as the architect of Sri Lanka’s suffering. Instead, IMF intervention is placed within a broader historical and structural context—one shaped primarily by domestic policy choices, institutional weaknesses, and political avoidance.

Public discourse often portrays IMF programmes as the starting point of economic hardship. Dr. Gunawardena corrects this misconception by restoring the correct chronology—an essential step for any honest assessment of the crisis.

The IMF did not arrive at the beginning of Sri Lanka’s collapse.

It arrived after the collapse had already begun.

By the time negotiations commenced, Sri Lanka had exhausted its foreign exchange reserves, lost access to international capital markets, officially defaulted on its external debt, and entered a phase of runaway inflation and acute shortages.

Fuel queues, shortages of essential medicines, and scarcities of basic food items were not the product of IMF conditionality. They were the direct outcome of prolonged foreign-exchange depletion combined with years of policy mismanagement. Import restrictions were imposed not because the IMF demanded them, but because the country simply could not pay its bills.

From this perspective, the IMF programme did not introduce austerity into a functioning economy. It formalised an adjustment that had already become unavoidable. The economy was already contracting, consumption was already constrained, and living standards were already falling. The IMF framework sought to impose order, sequencing, and credibility on a collapse that was already under way.

Seen through this lens, the return to the IMF was not a freely chosen policy option, but the end result of years of postponed decisions and missed opportunities.

A Long IMF Relationship, Short National Memory

Sri Lanka’s engagement with the IMF is neither new nor exceptional. For decades, governments of all political persuasions have turned to the Fund whenever balance-of-payments pressures became acute. Each engagement was presented as a temporary rescue—an extraordinary response to an unusual storm.

Yet, as Dr. Gunawardena meticulously documents, the storms were not unusual. What was striking was not the frequency of crises, but the remarkable consistency of their underlying causes.

Fiscal indiscipline persisted even during periods of growth. Government revenue remained structurally weak. Public debt expanded rapidly, often financing recurrent expenditure rather than productive investment. Meanwhile, the external sector failed to generate sufficient foreign exchange to sustain a consumption-led growth model.

IMF programmes brought temporary stability. Inflation eased. Reserves stabilised. Growth resumed. But once external pressure diminished, reform momentum faded. Political priorities shifted. Structural weaknesses quietly re-emerged.

This recurring pattern—crisis, adjustment, partial compliance, and relapse—became a defining feature of Sri Lanka’s economic management. The most recent crisis differed only in scale. This time, there was no room left to postpone adjustment.

Fiscal Fragility: The Core of the Crisis

A central focus of IMF Prakeerna Visadum is Sri Lanka’s chronically weak fiscal structure. Despite relatively strong social indicators and a capable administrative state, government revenue as a share of GDP remained exceptionally low.

Frequent tax changes, politically motivated exemptions, and weak enforcement steadily eroded the tax base. Instead of building a stable revenue system, governments relied increasingly on borrowing—both domestic and external.

Much of this borrowing financed subsidies, transfers, and public sector wages rather than productivity-enhancing investment. Over time, debt servicing crowded out development spending, shrinking fiscal space.

Fiscal reform failed not because it was technically impossible, Dr. Gunawardena argues, but because it was politically inconvenient. The costs were immediate and visible; the benefits long-term and diffuse. The eventual debt default was therefore not a surprise, but a delayed consequence.

The External Sector Trap

Sri Lanka’s narrow export base—apparel, tea, tourism, and remittances—generated foreign exchange but masked deeper weaknesses. Export diversification stagnated. Industrial upgrading lagged. Integration into global value chains remained limited.

Meanwhile, import-intensive consumption expanded. When external shocks arrived—global crises, pandemics, commodity price spikes—the economy had little resilience.

Exchange-rate flexibility alone cannot generate exports. Trade liberalisation without an industrial strategy redistributes pain rather than creates growth.

Monetary Policy and the Cost of Lost Credibility

Prolonged monetary accommodation, often driven by political pressure, fuelled inflation, depleted reserves, and eroded confidence. Once credibility was lost, restoring it required painful adjustment.

Macroeconomic credibility, Dr. Gunawardena reminds us, is a national asset. Once squandered, it is extraordinarily expensive to rebuild.

IMF Conditionality: Stabilisation Without Development?

IMF programmes stabilise economies, but they do not automatically deliver inclusive growth. In Sri Lanka, adjustment raised living costs and reduced real incomes. Social safety nets expanded, but gaps persisted.

This raises a critical question: can stabilisation succeed politically if it fails socially?

Political Economy: The Missing Middle

Reforms collided repeatedly with electoral incentives and patronage networks. IMF programmes exposed contradictions but could not resolve them. Without domestic ownership, reform risks becoming compliance rather than transformation.

Beyond Blame: A Diagnostic Moment

The book’s greatest strength lies in its refusal to engage in blame politics. IMF intervention is treated as a diagnostic signal, not a cause—a warning light illuminating unresolved structural failures.

The real challenge is not exiting an IMF programme, but exiting the cycle that makes IMF programmes inevitable.

A Strong Public Appeal: Why This Book Must Be Read

This is not an anti-IMF book.

It is not a pro-IMF book.

It is a pro-Sri Lanka book.

Published by Sarasaviya Publishers, IMF Prakeerna Visadum equips readers not with anger, but with clarity—offering history, evidence, and honest reflection when the country needs them most.

Conclusion: Will We Learn This Time?

The IMF can stabilise an economy.

It cannot build institutions.

It cannot create competitiveness.

It cannot deliver inclusive development.

Those responsibilities remain domestic.

The question before Sri Lanka is simple but profound:

Will we repeat the cycle, or finally learn the lesson?

The answer does not lie in Washington.

It lies with us.

By Professor Ranjith Bandara

Emeritus Professor, University of Colombo

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNew policy framework for stock market deposits seen as a boon for companies

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II

-

News4 days ago

News4 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament