Features

Meeting Mr Darcy

by Sumi Moonesinghe narrated to Savithri Rodrigo

While I was in training in England, there had been a change at the helm of the Ceylon Broadcasting Corporation. Neville Jayaweera had been transferred as Government Agent to Vavuniya and a new Director General had taken his place. His is name was Susil Moonesinghe.

As the end of my training period loomed close, I realized I wasn’t ready to leave England just yet. I wanted to stay on, just one more year, to complete my PhD. I sent in my request for an extension of one year to the new Director General but my request was denied. It was then that finality hit and I had to make arrangements to return.

I returned to my familiar surroundings at the station in 1971 and settled in. Even though I had been away for some time, nothing much had changed in a way. It’s quite amazing how good branding transcends time. The name change of Radio Ceylon to the Ceylon Broadcasting Corporation had made no difference to everyday conversation. Nearly everyone referred to CBC, which came into being through the CBC Act of 1966, as Radio Ceylon – the name stuck. What I didn’t foresee however was that the name Ceylon Broadcasting Corporation would be short-lived.

With the transitioning of Ceylon into the status of the Republic of Sri Lanka on May 22, 1972, CBC would get a yet another name change, just six years after, to what the station is presently known as – the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation.

A few days after my return, the Director General wanted to see me. This summoning was nothing out of the ordinary as I had been sent by CBC on training and he would want to know the value addition I now bring to the station. I walked the corridors leading to his office and the moment I set eyes on him, I couldn’t speak. This was unusual for me because throughout my years of school, university and England, I was not a woman who would get fazed or dumbstruck by any male. I had studied, lived and worked as the only female in the room and had always considered males as part of my life and not to be romanced around.

But this was totally different. Here I was in the Director General’s room, looking at the most handsome man I had seen in my entire life. If there is anything called love at first sight, this was it, although I didn’t recognize it at the time. I don’t remember much of that first meeting.

I returned to my usual routine. My engineering room was upstairs, in a building with three floors, at the back. It became a habit for me to peek out of the windows whenever I had the chance to check if the Director General was walking those long corridors that the station was famous for. A bonus was the car park being close to my office and at a vantage point from my window. Each morning I would see him park his car and I wouldn’t take my eyes off him as he walked all the way down to his office.

I would make various excuses to go out of my room, just to catch a glimpse of him or to go to his room to get information or ask a question. I could have done all this by phone or by sending a memo but I would drum up an excuse just to see him.

I think there was some mutual affection building up because Susil too started calling for me at various times and sometimes for issues totally unrelated to my role. He would ask me to sit through recruitment procedures and interviewee evaluations with him. While I worked in his room, I noticed the incessant telephone calls he would receive. Having been appointed by Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike into this post of Director General, Susil was a political appointee and as was the norm, he was inundated with politicians asking him to employ their various supporters at CBC.

I soon realized there was a subtle flirtation on his part as well He called me into his room one day and said, very stiffly, “Miss Senanayake, I have two tickets for a play. Would you like to go as I can’t seem to make it?” This was totally unusual as it was not work related and out of the blue. Not daring to ask him why he was giving me the tickets, or how he got them or what it was for, I simply said, “Yes, definitely, Sir. Thank you.”

He gave me the tickets and I went with my uncle to see the play. While we were quite engrossed in it, my uncle said, “Sumi, who is that man looking at you constantly?” I turned my head and saw Susil in the front row, staring at me but trying not to show that he was. It dawned on me that he gave me the tickets not because he couldn’t attend the play but because he knew I would be there too. I pretended not to notice, although my heart was beating very fast and by way of explanation told my uncle, “Oh that’s my boss at the station. He’s the Director General. He’s probably surprised to see me here.”

Work went on. SLBC had some visiting engineers from Yugoslavia and Susil placed me in charge of accompanying them to see the Esala Perahera, which is believed to be Asia’s grandest festival. A vantage point to view the pageant from the Queen’s Hotel in Kandy was generally reserved for CBC, as thousands gather for the parade that takes Buddha’s tooth relic, which is generally housed in the Temple of the Tooth, around the streets of Kandy.

The engineers and I were to spend the night at the Hotel Suisse, which had also been arranged. Susil apologized to the Yugoslav engineers of his inability to accompany them but assured them of being in good hands, pointing to me.

That night as we readied to watch the perahera, Susil surprised us by arriving at the Queen’s Hotel and taking a seat among us. He explained that he had completed his work and decided to make it to Kandy. I was secretly very happy to see him although I maintained my composure. The arrival of the whip crackers, those who herald the start of the pageant may have saved me from some embarrassment, if only he saw my face, beaming with delight.

In my hurry to pack for Kandy, I realized I hadn’t brought any toothpaste. We were by now back at Hotel Suisse and I was getting ready for bed. I am very fastidious so the thought of going to bed without brushing my teeth filled me with dread. I had an idea. I knocked on Susil’s door and asked him if I could borrow some toothpaste, which he willingly passed on to me. After brushing my teeth, I went back to his room and knocked on his door in order to return the toothpaste. Looking back, going back to that room to return the toothpaste was a rather flimsy excuse on my part, although at the time, my intentions, at least to me, seemed good.

Years later, Susil would recount this story with all the bells and whistles he could muster, saying, “I was seduced by Sumi with a tube of toothpaste!” He considered this the start of our romance and for my birthday one year, hung up a giant cut-out of a toothpaste tube at the entrance to the house. His sense of humour was endearing and definitely one of the reasons I fell in love with him.

Getting back to the perahera night, I had fallen asleep having brushed my teeth with Susil’s toothpaste. Around midnight, there was a knock on my door. Not used to having people knock on my door in the middle of the night, I asked tentatively, “Who is it?” Imagine my surprise when I heard, “It’s me, Susil. Please open the door. There’s been an accident.” I quickly opened the door and let in a very distressed Susil. “One of the officers at the Seeduwa Transmission Station has been killed. He was shot dead accidentally by a security guard on duty.” He slumped into a chair, looking ashen.

True to my nature, I took charge because I knew we had to manage a bad situation that could escalate into something truly worse. Several phone calls later and after some fires had been dampened, Susil asked me if he could remain in my room. “With all this going on, I can’t sleep,” he said. He made himself comfortable in his chair and we talked until morning, while I sat on the bed.

The conversation slowly gave way to other topics like my life. I told him of my fiance in England who was still employed at the State Engineering Corporation but on a leave of absence as he was reading for his PhD. By this time, we were chatting as if we had known each other for years. I gleaned that Susil had a wide network and basically knew everyone — an expansive directory of the who’s who. So I asked Susil if he could speak with the Chairman of State Engineering Corporation Dr. A N S Kulasinghe to obtain a leave extension for my fiance as he wanted to complete his studies but needed the job to come back to. “Ah, anything for love,” was Susil’s reply.

The next morning, not only did Susil call Dr. Kulasinghe and get an agreement for the extension, but also manipulated proceedings so that the Yugoslav engineers traveled back to Colombo in his official car with his driver, which meant, I would be traveling to Colombo with him. By this time, it was understood that a romance was blossoming.

While we were driving back, Susil remembered our conversations earlier. I had told Susil that my parents lived in Kegalle and he suddenly suggested we visit them. When we got to my parents’ home, I introduced Susil as my boss and the Director General of CBC. I believed that by meeting my parents, Susil would know my roots and the family I came from. There was nothing to hide. I was an open book.

My parents, who were used to always seeing me in the company of males, didn’t bat an eyelid when I brought him home. Over the course of a cup of tea, Susil, who was his absolute charming self, gained the complete confidence of my parents. Just as we were readying to leave, my mother looked at Susil and said, “Please see that she doesn’t get married to that Tamil boy. I am lighting two lamps appealing to the gods to break up that relationship.” Susil promptly replied, “Amma, please light one more lamp and the affair will end.”

He then asked my mother to give him my horoscope saying, “I have a good astrologer and I will check on whom she will get married to.” Of course, my mother promptly gave him my horoscope, such was the trust he had built up in the briefest of times.

While Susil knew all about me, I knew little of Susil or his lineage. I knew he had studied at Royal College and was a lawyer with an amazing gift of the gab. I did know he was married but in the middle of a budding romance, that didn’t seem to matter. But what I didn’t know was that he came from a very distinguished line of an elite Sinhala Buddhist family. His paternal grandmother was Anagarika Dharmapala’s sister. They were the children of Don Carolis Hewavitarane.

As a child, I remember learning about Anagarika Dharmapala, who was renowned for his non-violent Sinhala Buddhist nationalism and a leading figure in Sri Lanka’s independence movement against colonial rule. A global Buddhist missionary, he pioneered the revival of Buddhism. However, this was not what impressed me at all. It was simply Susil who held my undivided attention and now, love!

Susil had politics in his blood and in 1960 had contested the Polgahawela seat in the General Elections under the Mahajana Eksath Peramuna. His network and influence in politics saw him appointed organizer for the Southern Province of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party, in preparation for the 1970 General Elections. When the United Front, led by Sirimavo Bandaranaike won the 1970 elections, Susil’s hard work towards the win paid off and he was rewarded with the appointment of Director General of the Ceylon Broadcasting Corporation.

His business contacts too were expansive. But his strong urge to be politically active never left him and he continued being a livewire in pushing a people-centric political agenda with whatever party he supported.

(To be continued)

Features

When floods strike: How nations keep food on the table

Insights from global adaptation strategies

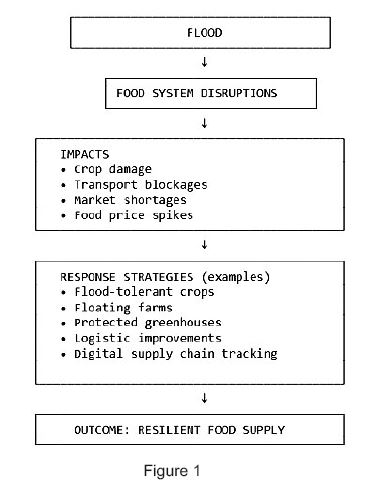

Sri Lanka has been heavily affected by floods, and extreme flooding is rapidly becoming one of the most disruptive climate hazards worldwide. The consequences extend far beyond damaged infrastructure and displaced communities. The food systems and supply networks are among the hardest hit. Floods disrupt food systems through multiple pathways. Croplands are submerged, livestock are lost, and soils become degraded due to erosion or sediment deposition. Infrastructural facilities like roads, bridges, retail shops, storage warehouses, and sales centres are damaged or rendered inaccessible. Without functioning food supply networks, even unaffected food-producing regions struggle to continue daily lives in such disasters. Poor households, particularly those dependent on farming or informal rural economies, face sharp food price increases and income loss, increasing vulnerability and food insecurity.

Many countries now recognie that traditional emergency responses alone are no longer enough. Instead, they are adopting a combination of short-term stabilisation measures and long-term strategies to strengthen food supply chains against recurrent floods. The most common immediate response is the provision of emergency food and cash assistance. Governments, the World Food Programme, and other humanitarian organisations often deliver food, ready-to-eat rations, livestock feed, and livelihood support to affected communities.

Alongside these immediate measures, some nations are implementing long-term strategic actions. These include technology- and data-driven approaches to improve flood preparedness. Early warning systems, using satellite data, hydrological models, and advanced weather forecasting, allow farmers and supply chain operators to prepare for potential disruptions. Digital platforms provide market intelligence, logistics updates, and risk notifications to producers, wholesalers, and transporters. This article highlights examples of such strategies from countries that experience frequent flooding.

China: Grain Reserves and Strategic Preparedness

China maintains a large strategic grain reserve system for rice, wheat, and maize; managed by NFSRA-National Food and Strategic Reserves Administration and Sinograin (China Grain Reserves Corporation (Sinograin Group), funded by the Chinese government, that underpins national food security and enables macro-control of markets during supply shocks. Moreover, improvements in supply chain digitization and hydrological monitoring, the country has strengthened its ability to maintain stable food availability during extreme weather events.

Bangladesh: Turning Vulnerability into Resilience

In recent years, Bangladesh has stood out as one of the world’s most flood-exposed countries, yet it has successfully turned vulnerability into adaptive resilience. Floating agriculture, flood-tolerant rice varieties, and community-run grain reserves now help stabilise food supplies when farmland is submerged. Investments in early-warning systems and river-basin management have further reduced crop losses and protected rural livelihoods.

Netherlands, Japan: High-Tech Models of Flood Resilience

The Netherlands offers a highly technical model. After catastrophic flooding in 1953, the country completely redesigned its water governance approach. Farmland is protected behind sea barriers, rivers are carefully controlled, and land-use zoning is adaptive. Vertical farming and climate-controlled greenhouses ensure year-round food production, even during extreme events. Japan provides another example of diversified flood resilience. Following repeated typhoon-induced floods, the country shifted toward protected agriculture, insurance-backed farming, and automated logistics systems. Cold storage networks and digital supply tracking ensure that food continues to reach consumers, even when roads are cut off. While these strategies require significant capital and investment, their gradual implementation provides substantial long-term benefits.

Pakistan, Thailand, Indonesia, and Vietnam: Reform in Response to Recurrent Floods

In contrast, Pakistan and Thailand illustrate both the consequences of climate vulnerability and the benefits of proactive reform. The 2022 floods in Pakistan submerged about one-third of the country, destroying crops and disrupting trade networks. In response, the country has placed greater emphasis on climate-resilient farming, water governance reforms, and satellite-based crop monitoring. Pakistan as well as India is promoting crop diversification and adjusting planting schedules to help farmers avoid the peak monsoon flood periods.

Thailand has invested in flood zoning and improved farm infrastructure that keep markets supplied even during severe flooding. Meanwhile, Indonesia and Vietnam are actively advancing flood-adapted land-use planning and climate-resilient agriculture. For instance, In Vietnam’s Mekong Delta, pilot projects integrate flood-risk mapping, adaptive cropping strategies, and ecosystem-based approaches to reduce vulnerability in agricultural and distribution areas. In Indonesia, government-supported initiatives and regional projects are strengthening flood-risk-informed spatial planning, adaptive farming practices, and community-based water management to improve resilience in flood-prone regions. (See Figure 1)

The Global Lesson: Resilience Requires Early Investment

The Global Lesson: Resilience Requires Early Investment

The global evidence is clear: countries that invest early in climate-adaptive agriculture and resilient logistics are better able to feed their populations, even during extreme floods. Building a resilient future depends not only on how we grow food but also on how we protect, store, and transport it. Strengthening infrastructure is therefore central to stabilising food supply chains while maintaining food quality, even during prolonged disruptions. Resilient storage systems, regional grain reserves, efficient cold chains, improved farming infrastructure, and digital supply mapping help reduce panic buying, food waste, and price shocks after floods, while ensuring that production capacity remains secure.

Persistent Challenges

However, despite these advances, many flood-exposed countries still face significant challenges. Resources are often insufficient to upgrade infrastructure or support vulnerable rural populations. Institutional coordination across the agriculture, disaster management, transport, and environmental sectors remains weak. Moreover, the frequency and scale of climate-driven floods are exceeding the design limits of older disaster-planning frameworks. As a result, the gap between exposure and resilience continues to widen. These challenges are highly relevant to Sri Lanka as well and require deliberate, gradual efforts to phase them out.

The Role of International Trade and global markets

When domestic production falls in such situations, international trade serves as an important buffer. When domestic production is temporarily reduced, imports and regional trade flows can help stabilise food availability. Such examples are available from other countries. For instance, In October 2024, floods in Bangladesh reportedly destroyed about 1.1 million tonnes of rice. In response, the government moved to import large volumes of rice and allowed accelerated or private-sector imports of rice to stabilize supply and curb food price inflation. This demonstrates how, when domestic production fails, international trade/livestock/food imports (from trade partners) acted as a crucial buffer to ensure availability of staple food for the population. However, this approach relies on well-functioning global markets, strong diplomatic relationships, and adequate foreign exchange, making it less reliable for economically fragile nations. For example, importing frozen vegetables to Sri Lanka from other countries can help address supply shortages, but considerations such as affordability, proper storage and selling mechanisms, cooking guidance, and nutritional benefits are essential, especially when these foods are not widely familiar to local populations.

Marketing and Distribution Strategies during Floods

Ensuring that food reaches consumers during floods requires innovative marketing and distribution strategies that address both supply- and demand-side challenges. Short-term interventions often include direct cash or food transfers, mobile markets, and temporary distribution centres in areas where conventional marketplaces become inaccessible. Price stabilisation measures, such as temporary caps or subsidies on staple foods, help prevent sharp inflation and protect vulnerable households. Awareness campaigns also play a role by educating consumers on safe storage, cooking methods, and the nutritional value of unfamiliar imported items, helping sustain effective demand.

Some countries have integrated technology to support these efforts; in this regard, adaptive supply chain strategies are increasingly used. Digital platforms provide farmers, wholesalers, and retailers with real-time market information, logistics updates, and flood-risk alerts, enabling them to reroute deliveries or adjust production schedules. Diversified delivery routes, using alternative roads, river transport, drones, or mobile cold-storage units, have proven essential for maintaining the flow of perishable goods such as vegetables, dairy, and frozen products. A notable example is Japan, where automated logistics systems and advanced cold-storage networks help keep supermarkets stocked even during severe typhoon-induced flooding.

The Importance of Research, Coordination, and Long-Term Commitment

Global experience also shows that research and development, strong institutional coordination, and sustained national commitment are fundamental pillars of flood-resilient food systems. Countries that have successfully reduced the impacts of recurrent floods consistently invest in agricultural innovation, cross-sector collaboration, and long-term planning.

Awareness Leads to Preparedness

As the summary, global evidence shows that countries that act early, plan strategically, and invest in resilience can protect both people and food systems. As Sri Lanka considers long-term strategies for food security under climate change, learning from flood-affected nations can help guide policy, planning, and public understanding. Awareness is the first step which preparedness must follow. These international experiences offer valuable lessons on how to protect food systems through proactive planning and integrated actions.

(Premaratne (BSc, MPhil, LLB) isSenior Lecturer in Agricultural Economics Department of Agricultural Systems, Faculty of Agriculture, Rajarata University. Views are personal.)

Key References·

Cabinet Secretariat, Government of Japan, 2021. Fundamental Plan for National Resilience – Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries / Logistics & Food Supply Chains. Tokyo: Cabinet Secretariat.

· Delta Programme Commissioner, 2022. Delta Programme 2023 (English – Print Version). The Hague: Netherlands Delta Programme.

· Hasanuddin University, 2025. ‘Sustainable resilience in flood-prone rice farming: adaptive strategies and risk-sharing around Tempe Lake, Indonesia’, Sustainability. Available at: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/17/6/2456 [Accessed 3 December 2025].

· Mekong Urban Flood Resilience and Drainage Programme (TUEWAS), 2019–2021. Integrated urban flood and drainage planning for Mekong cities. TUEWAS / MRC initiative.

· Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, People’s Republic of China, 2025. ‘China’s summer grain procurement surpasses 50 mln tonnes’, English Ministry website, 4 July.

· National Food and Strategic Reserves Administration (China) 2024, ‘China purchases over 400 mln tonnes of grain in 2023’, GOV.cn, 9 January. Available at: https://english.www.gov.cn/archive/statistics/202401/09/content_WS659d1020c6d0868f4e8e2e46.html

· Pakistan: 2022 Floods Response Plan, 2022. United Nations / Government of Pakistan, UN Digital Library.

· Shigemitsu, M. & Gray, E., 2021. ‘Building the resilience of Japan’s agricultural sector to typhoons and heavy rain’, OECD Food, Agriculture and Fisheries Papers, No. 159. Paris: OECD Publishing.

· UNDP & GCF, 2023. Enhancing Climate Resilience in Thailand through Effective Water Management and Sustainable Agriculture (E WMSA): Project Factsheet. UNDP, Bangkok.

· United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), 2025. ‘Rice Bank revives hope in flood hit hill tracts, Bangladesh’, UNDP, 19 June.

· World Bank, 2022. ‘Bangladesh: World Bank supports food security and higher incomes of farmers vulnerable to climate change’, World Bank press release, 15 March.

Features

Can we forecast weather precisely?

Weather forecasts are useful. People attentively listen to them but complain that they go wrong or are not taken seriously. Forecasts today are more probabilistically reliable than decades ago. The advancement of atmospheric science, satellite imaging, radar maps and instantly updated databases has improved the art of predicting weather.

Yet can we predict weather patterns precisely? A branch of mathematics known as chaos theory says that weather can never be foretold with certainty.

The classical mechanics of Issac Newton governing the motion of all forms of matter, solid, liquid or gaseous, is a deterministic theory. If the initial conditions are known, the behaviour of the system at later instants of time can be precisely predicted. Based on this theory, occurrences of solar eclipses a century later have been predicted to an accuracy of minutes and seconds.

The thinking that the mechanical behaviour of systems in nature could always be accurately predicted based on their state at a previous instant of time was shaken by the work of the genius French Mathematician Henri Poincare (1864- 1902).

Eclipses are predicted with pinpoint accuracy based on analysis of a two-body system (Earth- Moon) governed by Newton’s laws. Poincare found that the equivalent problem of three astronomical bodies cannot be solved exactly – sometimes even the slightest variation of an initial condition yields a drastically different solution.

A profound conclusion was that the behaviour of physical systems governed by deterministic laws does not always allow practically meaningful predictions because even a minute unaccountable change of parameters leads to completely different results.

Until recent times, physicists overlooked Poincare’s work and continued to believe that the determinism of the laws of classical physics would allow them to analyse complex problems and derive future happenings, provided necessary computations are facilitated. When computers became available, the meteorologists conducted simulations aiming for accurate weather forecasting. The American mathematician Edward Lorenz, who turned into a reputed meteorologist, carried out such studies in the early 1960s, arrived at an unexpected result. His equations describing atmospheric dynamics demonstrated a strange behaviour. He found that even a minute change (even one part in a million) in initial parameters leads to a completely different weather pattern in the atmosphere. Lorenz announced his finding saying, A flap of a butterfly wing in one corner of the world could cause a cyclone in a far distant location weeks later! Lorenz’s work opened the way for the development branch of mathematics referred to as chaos theory – an expansion of the idea first disclosed by Henri Poincare.

We understand the dynamics of a cyclone as a giant whirlpool in the atmosphere, how it evolves and the conditions favourable for their origination. They are created as unpredictable thermodynamically favourable relaxation of instabilities in the atmosphere. The fundamental limitations dictated by chaos theory forbid accurate forecasting of the time and point of its appearance and the intensity. Once a cyclone forms, it can be tracked and the path of movement can be grossly ascertained by frequent observations. However, absolutely certain predictions are impossible.

A peculiarity of weather is that the chaotic nature of atmospheric dynamics does not permit ‘long – term’ forecasting with a high degree of certainty. The ‘long-term’ in this context, depending on situation, could be hours, days or weeks. Nonetheless, weather forecasts are invaluable for preparedness and avoiding unlikely, unfortunate events that might befall. A massive reaction to every unlikely event envisaged is also not warranted. Such an attitude leads to social chaos. The society far more complex than weather is heavily susceptible to chaotic phenomena.

by Prof. Kirthi Tennakone (ktenna@yahoo.co.uk)

Features

When the Waters Rise: Floods, Fear and the ancient survivors of Sri Lanka

The water came quietly at first, a steady rise along the riverbanks, familiar to communities who have lived beside Sri Lanka’s great waterways for generations. But within hours, these same rivers had swollen into raging, unpredictable forces. The Kelani Ganga overflowed. The Nilwala broke its margins. The Bentara, Kalu, and Mahaweli formed churning, chocolate-brown channels cutting through thousands of homes.

When the floods finally began to recede, villagers emerged to assess the damage, only to be confronted by another challenge: crocodiles. From Panadura’s back lanes to the suburbs of Colombo, and from the lagoons around Kalutara to the paddy fields of the dry zone, reports poured in of crocodiles resting on bunds, climbing over fences, or drifting silently into garden wells.

For many, these encounters were terrifying. But to Sri Lanka’s top herpetologists, the message was clear: this is what happens when climate extremes collide with shrinking habitats.

“Crocodiles are not invading us … we are invading floodplains”

Sri Lanka’s foremost crocodile expert, Dr. Anslem de Silva, Regional Chairman for South Asia and Iran of the IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialist Group, has been studying crocodiles for over half a century. His warning is blunt.

“When rivers turn into violent torrents, crocodiles simply seek safety,” he says. “They avoid fast-moving water the same way humans do. During floods, they climb onto land or move into calm backwaters. People must understand this behaviour is natural, not aggressive.”

In the past week alone, Saltwater crocodiles have been sighted entering the Wellawatte Canal, drifting into the Panadura estuary, and appearing unexpectedly along Bolgoda Lake.

“Saltwater crocodiles often get washed out to sea during big floods,” Dr. de Silva explains. “Once the current weakens, they re-enter through the nearest lagoon or canal system. With rapid urbanisation along these waterways, these interactions are now far more visible.”

- An adult Salt Water Crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) (Photo -Madura de Silva)

- Adult Mugger (Crocodylus plaustris) Photo -Laxhman Nadaraja

- A Warning sign board

- A Mugger holding a a large Russell ’s viper (Photo- R. M. Gunasinghe)

- Anslem de Silva

- Suranjan Karunarathna

This clash between wildlife instinct and human expansion forms the backdrop of a crisis now unfolding across the island.

A conflict centuries old—now reshaped by climate change

Sri Lanka’s relationship with crocodiles is older than most of its kingdoms. The Cūḷavaṃsa describes armies halted by “flesh-eating crocodiles.” Ancient medical texts explain crocodile bite treatments. Fishermen and farmers around the Nilwala, Walawe, Maduganga, Batticaloa Lagoon, and Kalu Ganga have long accepted kimbula as part of their environment.

But the modern conflict has intensified dramatically.

A comprehensive countrywide survey by Dr. de Silva recorded 150 human–crocodile attacks, with 50 fatal, between 2008 and 2010. Over 52 percent occurred when people were bathing, and 83 percent of victims were men engaged in routine activities—washing, fishing, or walking along shallow margins.

Researchers consistently emphasise: most attacks happen not because crocodiles are unpredictable, but because humans underestimate them.

Yet this year’s flooding has magnified risks in new ways.

“Floods change everything” — Dr. Nimal D. Rathnayake

Herpetologist Dr. Nimal Rathnayake says the recent deluge cannot be understood in isolation.

“Floodwaters temporarily expand the crocodile’s world,” he says. “Areas people consider safe—paddy boundaries, footpaths, canal edges, abandoned land—suddenly become waterways.”

Once the water retreats, displaced crocodiles may end up in surprising places.

“We’ve documented crocodiles stranded in garden wells, drainage channels, unused culverts and even construction pits. These are not animals trying to attack. They are animals trying to survive.”

According to him, the real crisis is not the crocodile—it is the loss of wetlands, the destruction of natural river buffers, and the pollution of river systems.

“When you fill a marsh, block a canal, or replace vegetation with concrete, you force wildlife into narrower corridors. During floods, these become conflict hotspots.”

Past research by the Crocodile Specialist Group shows that more than 300 crocodiles have been killed in retaliation or for meat over the past decade. Such killings spike after major floods, when fear and misunderstanding are highest.

“Not monsters—ecosystem engineers” — Suranjan Karunaratne

On social media, flood-displaced crocodiles often go viral as “rogue beasts.” But conservationist Suranjan Karunaratne, also of the IUCN/SSC Crocodile Specialist Group, says such narratives are misleading.

“Crocodiles are apex predators shaped by millions of years of evolution,” he says. “They are shy, intelligent animals. The problem is predictable human behaviour.”

In countless attack investigations, Karunaratne and colleagues found a repeated pattern: the Three Sames—the same place, the same time, the same activity.

“People use the same bathing spot every single day. Crocodiles watch, learn, and plan. They hunt with extraordinary patience. When an attack occurs, it’s rarely random. It is the culmination of observation.”

He stresses that crocodiles are indispensable to healthy wetlands. They: control destructive catfish populations, recycle nutrients, clean carcasses and diseased fish, maintain biodiversity, create drought refuges through burrows used by amphibians and reptiles.

“Removing crocodiles destroys an entire chain of ecological services. They are not expendable.”

Karunaratne notes that after the civil conflict, Mugger populations in the north rebounded—proof that crocodiles recover when given space, solitude, and habitat.

Floods expose a neglected truth: CEEs save lives—if maintained In high-risk communities, Crocodile Exclusion Enclosures (CEEs) are often the only physical barrier between people and crocodiles. Built along riverbanks or tanks, these enclosures allow families to bathe, wash, and collect water safely.

Yet Dr. de Silva recounts a tragic incident along the Nilwala River where a girl was killed inside a poorly maintained enclosure. A rusted iron panel had created a hole just large enough for a crocodile to enter.

“CEEs are a life-saving intervention,” he says. “But they must be maintained. A neglected enclosure is worse than none at all.”

Despite their proven effectiveness, many CEEs remain abandoned, broken or unused.

Climate change is reshaping crocodile behaviour—and ours

Sri Lanka’s floods are no longer “cycles” as described in folklore. They are increasingly intense, unpredictable and climate-driven. The warming atmosphere delivers heavier rainfall in short bursts. Deforested hillsides and filled wetlands cannot absorb it.

Rivers swell rapidly and empty violently.

Crocodiles respond as they have always done: by moving to calmer water, by climbing onto land, by using drainage channels, by shifting between lagoons and canals, by following the shape of the water.

But human expansion has filled, blocked, or polluted these escape routes.

What once were crocodile flood refuges—marshes, mangroves, oxbow wetlands and abandoned river channels—are now housing schemes, fisheries, roads, and dumpsites.

Garbage, sand mining and invasive species worsen the crisis

The research contained in the uploaded reports paints a grim but accurate picture. Crocodiles are increasingly seen around garbage dumps, where invasive plants and waste accumulate. Polluted water attracts fish, which in turn draw crocodiles.

Excessive sand mining in river mouths and salinity intrusion expose crocodile nesting habitats. In some areas, agricultural chemicals contaminate wetlands beyond their natural capacity to recover.

In Borupana Ela, a short study found 29 Saltwater crocodiles killed in fishing gear within just 37 days.

Such numbers suggest a structural crisis—not a series of accidents.

Unplanned translocations: a dangerous human mistake

For years, local authorities attempted to reduce conflict by capturing crocodiles and releasing them elsewhere. Experts say this was misguided.

“Most Saltwater crocodiles have homing instincts,” explains Karunaratne. “Australian studies show many return to their original site—even if released dozens of kilometres away.”

Over the past decade, at least 26 Saltwater crocodiles have been released into inland freshwater bodies—home to the Mugger crocodile. This disrupts natural distribution, increases competition, and creates new conflict zones.

Living with crocodiles: a national strategy long overdue

All three experts—Dr. de Silva, Dr. Rathnayake and Karunaratne—agree that Sri Lanka urgently needs a coordinated, national-level mitigation plan.

* Protect natural buffers

Replant mangroves, restore riverine forests, enforce river margin laws.

* Maintain CEEs

They must be inspected, repaired and used regularly.

* Public education

Villagers should learn crocodile behaviour just as they learn about monsoons and tides.

* End harmful translocations

Let crocodiles remain in their natural ranges.

* Improve waste management

Dumps attract crocodiles and invasive species.

* Incentivise community monitoring

Trained local volunteers can track sightings and alert authorities early.

* Integrate crocodile safety into disaster management

Flood briefings should include alerts on reptile movement.

“The floods will come again. Our response must change.”

As the island cleans up and rebuilds, the deeper lesson lies beneath the brown floodwaters. Crocodiles are not new to Sri Lanka—but the conditions we are creating are.

Rivers once buffered by mangroves now rush through concrete channels. Tanks once supporting Mugger populations are choked with invasive plants. Wetlands once absorbing floodwaters are now levelled for construction.

Crocodiles move because the water moves. And the water moves differently today.

Dr. Rathnayake puts it simply:”We cannot treat every flooded crocodile as a threat to be eliminated. These animals are displaced, stressed, and trying to survive.”

Dr. de Silva adds:”Saving humans and saving crocodiles are not competing goals. Both depend on understanding behaviour—ours and theirs.”

And in a closing reflection, Suranjan Karunaratne says:”Crocodiles have survived 250 million years, outliving dinosaurs. Whether they survive the next 50 years in Sri Lanka depends entirely on us.”

For now, as the waters recede and the scars of the floods remain, Sri Lanka faces a choice: coexist with the ancient guardians of its waterways, or push them into extinction through fear, misunderstanding and neglect.

By Ifham Nizam

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWeather disasters: Sri Lanka flooded by policy blunders, weak enforcement and environmental crime – Climate Expert

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoLevel I landslide RED warnings issued to the districts of Badulla, Colombo, Gampaha, Kalutara, Kandy, Kegalle, Kurnegala, Natale, Monaragala, Nuwara Eliya and Ratnapura

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoINS VIKRANT deploys helicopters for disaster relief operations

-

News3 days ago

Lunuwila tragedy not caused by those videoing Bell 212: SLAF

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoLevel III landslide early warnings issued to the districts of Badulla, Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoDitwah: An unusual cyclone

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoUpdated Payment Instructions for Disaster Relief Contributions