Opinion

JULY 1983: AS THE WORLD SAW SRI LANKA

Monday 25th July 1983 began like just another day. But what we didn’t know was that it was to be the last day of an era. By mid-morning from my second-floor office in Fort I could see the city being put to the torch. Already my two sisters’ homes in the suburbs had been attacked and they were taking shelter with Sinhalese and Burgher neighbours.

After ensuring that the female staff was safely escorted home, I walked to my wife’s office in Kompannavidiya. Outside the Air Force Headquarters on Sir Chittampalam Gardiner Mawatha, gangs were stopping cars and setting them on fire. A Police jeep drove through the inferno; but the mob did not pause from their orgy of destruction. On Malay Street groups were looting and then setting shops ablaze. I watched truckloads of troops chanting ‘Jayaweva’ drive out of Army Headquarters, exhorting and encouraging the mobs.

A Sinhalese colleague accompanied us back home where we packed one briefcase with essential documents and one basket with food and necessities for Nishara, our nine-month-old baby. If we had to flee this was all we would take. When a house in the adjacent road was attacked, we took refuge with a Sinhalese neighbour.

We were among the fortunate. We survived. This article remembers the many who did not return to their homes; who came home to charred ruins; who fled to refugee camps and then into exile overseas. It honours the memories of the men, women, children and domestic animals who perished in Sri Lanka’s Holocaust.

By Jayantha Somasundaram

This article is based on reporting by the international media on the events in Sri Lanka 40 years ago.)

“I am not worried about the opinion of the Jaffna people… now we cannot think of them, not about their lives or their opinion… the more you put pressure in the north, the happier the Sinhala people will be here… Really, if I starve the Tamils out, the Sinhala people will be happy.” – President J.R. Jayewardene, Daily Telegraph (London) 11 July 1983

“Someone seemed to have planned the whole thing and waited only for an opportunity. And the opportunity came on the night of 23 July,” (Race & Class London XXVI.I [1984]). Thirteen soldiers of the 1st Battalion Sri Lanka Light Infantry were killed in a landmine explosion in Thirunelveli. Enraged troops struck back immediately. David Beresford wrote that “members of the Tamil community in Jaffna told the British Guardian troops killed a number of students waiting at a bus stop; the students aged between 18 and 20 had been lined up and fired upon. Six were killed and another two injured. Shortly afterwards troops drove through a village about five miles outside Jaffna shooting at random. Two were reported killed. Soldiers in civilian clothes were out in jeeps and raided a number of houses shooting inhabitants. In one house a family planning official was allegedly shot dead while lying on his bed and his 72-year-old father-in-law a headmaster shot sitting outside on the veranda. About 16 people were killed.

“Asked yesterday why no inquests have been held, President Jayewardene said: I didn’t know until a couple of days ago. It is too late now.” The violence then spread to Trincomalee where since early June Tamils had been subject to violence by hoodlums from the market area. On the 3rd the Mansion Hotel had been attacked. Now sailors went on a rampage destroying Hindu Temples, homes and shops. “In Trincomalee” reported The Irish Times (29.7.83), “130 sailors were under arrest after breaking out of their barracks on Monday and attacking shops and homes.”

“Only one in every 100 policemen is a Tamil. When security forces were ordered last week to protect Tamils in Trincomalee and other cities, they reportedly joined in the looting and burning,” said the London Observer (31.7.83).

A crowd had gathered at Kanatte Cemetery in Colombo for the funeral of the soldiers to be held on the 24th evening. “That night, a section of this crowd started setting fire to Tamil houses at the Borella end of Rosmead Place,” (Race & Class ibid).

On the morning of the 25th, mobs began moving right through Colombo and its suburbs waylaying Tamils and attacking them. They stopped vehicles and set ablaze those belonging to Tamils. They went through commercial areas looted shops and set them on fire. Residential areas were worked systematically and homes occupied by Tamils were attacked, looted and burned. Tamils who fell into the hands of these mobs were beaten and killed.

“There is no doubt that someone had identified the Tamil houses, shops and factories earlier. Seventeen industrial complexes belonging to some of the leading Tamil and Indian industrialists were razed to the ground, including those of the multi-millionaire and firm supporter of the ruling party, A.Y. S. Gnanam (the only capitalist in Sri Lanka to whom the World Bank offered a loan), and the influential Maharaja Organisation. The Indian-owned textile mills of Hirdramani Ltd, which used a labour force of 4,000 in the suburbs of Colombo was gutted. So was K. G. Industries Ltd, Hentley Garments, one of the biggest garment exporters…Several cinemas owned by Tamils were destroyed…Probably the worst affected area was the Pettah, the commercial centre of Colombo, where Tamil and Indian traders played a dominant role. Hardly a single Tamil or Indian establishment was left standing. A most distressing aspect of the vandalism was the burning and the destruction of the houses and dispensaries of eminent Tamil doctors – some with over a quarter of a century of service in Sinhala areas.” (Race & Class ibid)

All over the island

By midday the skyline was marked by columns of smoke as factories, shops and houses burned to the ground. A curfew was imposed at 2.00 pm but the terror did not abate, the attacks continued into the next day. “In the capital Colombo, Tamils are said to have been dragged from their cars and incinerated with petrol,” reported the London Economist (30.7.83).

Anthony Mascarenhas of the London Sunday Times wrote: “Throughout Monday Tamil shops were attacked and burned. Those who resisted perished with their property. Buses and cars were stopped and their Tamil passengers beaten up. Cars were burned and strewn all over the city. The army moved in by noon but troops turned a blind eye. Next day Tuesday, the looters took over defying the curfew. By midweek the trouble had spread all over the island. Affluent Tamils in Colombo who had hidden to escape the mobs were now singled out for attacks in their homes, which were looted and burned.”

“The capital was strewn with the wreckage of scores of shops and houses set ablaze, gutted or looted in the rioting.”(New York Times 28/7/83)

John Elliot of the London Financial Times reported from Colombo: “In each street individual business premises were burned down while others alongside were unscathed. Troops and police either joined the rioters or stood idly by. President Jayawardene failed either intentionally or because he had lost control to stem the damage.”

“By Monday night” said Asiaweek from Hong Kong (12.8.83) “the official death toll in the Greater Colombo area alone was 36 with hundreds more injured and unofficial estimates put the figure at three or four times higher. Most of the dead were helpless Tamils stranded in the city and caught by mobs while trying to flee. In the Borella area two Tamil shop-owners were burnt alive when a mob set fire to a row of shops. In Maradana a Tamil was chased by a mob brought down with stones and then hacked to death.

“On Monday while Borella was being put to the torch rioting broke out in adjacent Welikada prison. Some 400 prisoners from a section reserved for common criminals broke into the maximum-security section. Of the Tamil inmates many of whom were still awaiting trial, 37 were killed, either bludgeoned to death with iron bars or literally trampled to death.

“By Tuesday morning virtually every town in Sri Lanka with a Tamil presence bore scars of rioting. The main target, Tamil owned shops and businesses. According to one estimate more than half the country’s Tamil owned shops were gutted.

“Meanwhile the violence went on” continued Asiaweek (12.8.83). “On Thursday an incoming train from Kandy was stopped just outside the Fort station by security forces acting on a tip that Tamil terrorists were on board. One Tamil was reportedly apprehended carrying hand grenades and an automatic rifle. In the process of arresting them however, pandemonium broke out in the train and the Tamil passengers fled. Ten were run down by a mob of some 2,000 Sinhalese who doused each one with petrol and set them alight while still alive. As the victims screamed in pain the Sinhalese crowd cheered and flashed victory signs, then spilled into the streets looting and burning Tamil shops.”

Welikada Prison

“The same day saw more trouble at Welikada,” explained Asiaweek. “Sinhalese prisoners for the second time in three days broke into the maximum-security wing, this time murdering seventeen Tamil detainees. With three other Tamil inmates killed in the Jaffna jail, the total number of Tamils clubbed or trampled to death by rampaging Sinhalese prisoners was 55.”

David Beresford of The Guardian (13.8.83) recalled that ‘Kutumani’ Yogachandran and Ganeshnathan Jeganathan in speeches from the dock had announced that they would donate their eyes in the hope that they would be grafted onto those who would see the birth of Tamil Eelam. “Reports from Batticaloa jail where the survivors of the Welikada massacre are now being kept say that the two men were forced to kneel and their eyes were gorged out with iron bars before they were killed.”

On his return to London Pat O’Leary told the Associated Press “People were dragged out of their homes and then the houses were burned down. I watched a group of Sinhalese people chase a group of three Tamils. They caught one beat him up threw him to the ground and stoned him. It was terrible. Nobody did a thing to help. Even the Police turned a blind eye.”

A Norwegian woman Eli Skarstein on her return to Oslo told the press that “A mini bus full of Tamils was forced to stop just in front of us in Colombo. A Sinhalese mob poured petrol over the bus and set it on fire. They blocked the car doors and prevented the Tamils from leaving the vehicle. Hundreds of spectators witnessed as 20 Tamils were burned to death.”

“For days soldiers and policemen were not overwhelmed: they were unengaged or, in some cases apparently aiding the attackers,” reported the London Economist (6.8.83). “Numerous eye witnesses attest that soldiers and policemen stood by while Colombo burned. After two days of violence and the murder of 35 Tamils in a maximum-security jail, the only editorial in the government-run newspaper was on ‘saving our forest cover’.

“It was five days after the precipitating ambush and a day after a second prison massacre that the people of Sri Lanka heard from their President. On July 28th Mr. Jayewardene spoke on television to denounce separatism and proscribing any party that endorsed it in order to ‘appease the natural desire and request’ of the Sinhalese ‘to prevent the country being divided’. Not a syllable of sympathy for the Tamil people or any explicit rejection of the spirit of vengeance. Next day Colombo was a battle field: more than 100 people are estimated to have been killed on that Friday alone.”

Tigers in the City

On Friday 29th when a soldier accidently shot himself in the Pettah the rumour spread that ‘Tigers’ were in the City. Indian journalist M. Rahman reported how in response soldiers and Sinhalese mobs retreated to the many bridges leading out of Colombo, killing Tamils desperately trying to get back to their homes.

A middle-aged businessman whom T.R. Lanser interviewed for the London Observer (7.8.83) said “On Friday about noon a mob came to attack Tamil people in the hospital. A Tamil Inspector of Police who was visiting me was murdered, cut with knives, just as he was talking to me. He faced them and he gave us time. Even with this broken foot I ran and hid…”

Michael Hamlyn wrote in the London Times (1.8.83) “burnings and killings continued over the weekend despite a 60-hour curfew. The trouble spread on Saturday to Nuwara Eliya. There were further incidents of violence against Tamils and their property in Chilaw, Matale and Kalutara.

”There was a mass exodus of Tamils displaced from their homes. Thirty busloads of refugees were taken from a camp and embarked on a ship for the North.” The International Herald Tribune (15.8.83) in Paris quoted A. Amirthalingam leader of the TULF (Tamil United Liberation Front) and leader of the Opposition in Parliament, as saying that 2,000 people had died in two months of ethnic unrest. He said the figure included deaths in the whole island since anti-Tamil violence broke out in Trincomalee on June 3rd and culminated in riots throughout the island at the end of July.

Opinion

Future must be won

Excerpts from the speech of the Chairman of the Communist Party of Sri Lanka, D.E.W. Gunasekera, at the 23rd Convention of the Party

This is not merely a routine gathering. Our annual congress has always been a decisive moment in Sri Lanka’s political history. For 83 years, since the formation of our Party in 1943, we have held 22 conventions. Each one reflected the political turning points of our time. Today, as we assemble for the 23rd Congress, we do so at another historic crossroads – amidst a deepening economic crisis at home and profound transformations in the global order.

Our Historical Trajectory: From Anti-imperialism to the Present

The 4th Party Convention in 1950 was a decisive milestone. It marked Sri Lanka’s conscious turn toward anti-imperialism and clarified that the socialist objective and revolution would be a long-term struggle. By the 1950s, the Left movement in Sri Lanka had already socialized the concept of socialist transformation among the masses. But the Communist Party had to dedicate nearly two decades to building the ideological momentum required for an anti-imperialist revolution.

As a result of that consistent struggle, we were able to influence and contribute to the anti-imperialist objectives achieved between 1956 and 1976. From the founding of the Left movement in 1935 until 1975, our principal struggle was against imperialism – and later against neo-imperialism in its modernised forms,

The 5th Convention in 1955 in Akuressa, Matara, adopted the Idirimaga (“The Way Forward”) preliminary programme — a reform agenda intended to be socialised among the people, raising public consciousness and organising progressive forces.

At the 1975 Convention, we presented the programme Satan Maga (“The Path of Battle”).

The 1978 Convention focused on confronting the emerging neoliberal order that followed the open economy reforms.

The 1991 Convention, following the fall of the Soviet Union, grappled with international developments and the emerging global order. We understand the new balance of forces.

The 20th Convention in 2014, in Ratnapura, addressed the shifting global balance of power and the implications for the Global South, including the emergence of a multipolar world. At that time, contradictions were developing between the United People’s Freedom Alliance (UPFA), government led by Mahinda Rajapaksa, and the people, and we warned of these contradictions and flagged the dangers inherent in the trajectory of governance.

Each convention responded to its historical moment. Today, the 23rd must responded to ours.

Sri Lanka in the Global Anti-imperialist Tradition

Sri Lanka was a founding participant in the Bandung Conference of 1955, a milestone in the anti-colonial solidarity of Asia and Africa. In 1976, Sri Lanka hosted the 5th Summit of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) in Colombo, under Prime Minister Sirimavo Bandaranaike.

At that time, Fidel Castro emerged as a leading voice within NAM. At the 6th Summit in Havana in 1979, chaired by Castro, a powerful critique was articulated regarding the international economic and social crises confronting newly sovereign nations.

Three central obstacles were identified:

1. The unjust global economic order.

2. The unequal global balance of power,

3. The exploitative global financial architecture.

After 1979, the Non-Aligned Movement gradually weakened in influence. Yet nearly five decades later, those structural realities remain. In fact, they have intensified.

The Changing Global Order: Facts and Realities

Today we are witnessing structural Changes in the world system.

1. The Shift in Economic Gravity

The global economic centre of gravity has shifted toward Asia after centuries of Western dominance. Developing countries collectively represent approximately 85% of the world’s population and roughly 40-45% of global GDP depending on measurement methods.

2. ASEAN and Regional Integration

The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), now comprising 10 member states (with Timor-Leste in the accession process), has deepened economic integration. In addition, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) – which includes ASEAN plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand – is widely recognised as the largest free trade agreement in the world by participating economies.

3. BRICS Expansion

BRICS – originally Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa – has expanded. As of 2025, full members include Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Egypt, Ethiopia and Iran. Additional partner countries are associated through BRICS mechanisms.

Depending on measurement methodology (particularly Purchasing Power Parity), BRICS members together account for approximately 45-46% of global GDP (PPP terms) and roughly 45% of the world’s population. If broader partners are included, demographics coverage increases further. lt is undeniably a major emerging bloc.

4. Regional Blocs Across the Global South

Latin America, Africa, Eurasia and Asia have all consolidated regional trade and political groupings. The Global South is no longer politically fragmented in the way it once was.

5. Alternative Development Banks

Two important institutions have emerged as alternatives to the Bretton Woods system:

• The New Development Bank (NDB) was established by BRICS in 2014.

• The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), operational since 2016, now with over 100 approved members.

These institutions do not yet replace the IMF or World Bank but they represent movement toward diversification.

6. Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO)

The SCO has evolved into a major Eurasian security and political bloc, including China, Russia, India. Pakistan and several Central Asian states.

7. Do-dollarization and Reserve Trends

The US dollar remains dominant foreign exchange reserves at approximately 58%, according to IMF data. This share has declined gradually over two decades. Diversification into other currencies and increased gold holdings indicate slow structural shifts.

8. Global North and Global South

The Global North – broadly the United States, Canada European Union and Japan – accounts for roughly 15% of the world’s population and about 35-40% of global GDP.

The Global South – Latin America, Africa, Asia and parts of Eurasia – contains approximately 85% of humanity and an expanding share of global production.

These shifts create objective conditions for the restructuring of the global financial architecture – but they do not automatically guarantee justice.

Sri Lanka’s Triple Crisis

Sri Lanka’s crisis culminated on 12 April 2022, when the government declared suspension of external debt payments – effectively announcing sovereign default.

Since then, political leadership has changed. President Gotabaya Rajapaksa resigned. President Ranil Wickremesinghe governed during the IMF stabilization period. In September 2024, Anura Kumara Dissanayake of the National People’s Power (NPP) was elected President.

We have had three presidents since the crisis began.

Yet four years later, the structural crisis remains unresolved,

‘The crisis had three dimensions:

1. Fiscal crisis – the Treasury ran out of rupees.

2. Foreign exchange crisis – the Central Bank ran out of dollars.

3. Solvency crisis – excessive domestic and external borrowing rendered repayment impossible.

Despite debt suspension, Sri Lanka’s total debt stock – both domestic and external – remains extremely high relative to GDP, External Debt restructuring provides temporary could reappear around 2027-2028 when grace periods taper.

In the Context of global geopolitical competition in the Indian Ocean region, Sri Lanka’s economic vulnerability becomes even more dangerous,

The Central Task: Economic Sovereignty

Therefore, the 23rd Congress must clearly declare that the struggle for economic sovereignty is the principal task before our nation.

Economic sovereignty means:

• Production economy towards industrialization and manufacturing.

• Food and energy security.

• Democratic control of development policy.

• Fair taxation.

• A foreign policy based on non-alignment and national dignity.

Only a centre-left government, rooted in anti-imperialist and nationalist forces, can lead this struggle.

But unity is required and self-criticism.

All progressive movements must engage in honest reflection. Without such reflection, we risk irrelevance. If we fail to build a broad coalition, if we continue Political fragmentation, the vacuum may be filled by extreme right forces. These forces are already growing globally.

Even governments elected on left-leaning mandates can drift rightward under systemic pressure. Therefore, vigilance and organised mass politics are essential.

Comrades,

History does not move automatically toward justice. It moves through organised struggle.

The 23rd Congress of the Communist Party of Sri Lanka must reaffirm.

• Our commitment to socialism.

• Our dedication to anti-imperialism.

• Our strategic clarity in navigating a multipolar world.

• Our resolve to secure economic sovereignty for Sri Lanka.

Let this Congress become a turning point – not merely in rhetoric, but in organisation and action.

The future will not be given to us.

It must be won.

Opinion

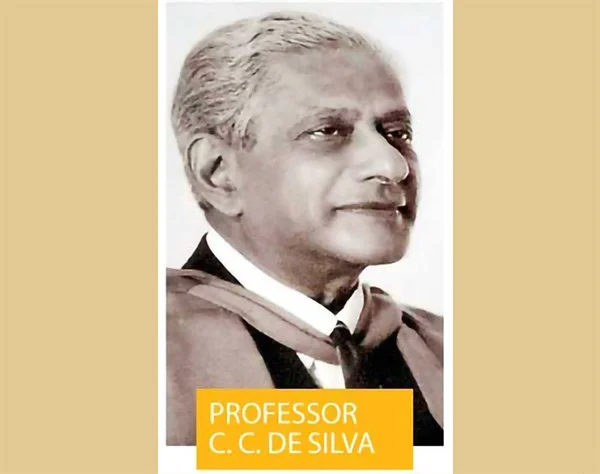

Singular Man: A 122nd Birth Anniversary accolade to Professor C. C. De Silva

On the 25th of February, the 122nd birth anniversary of Emeritus Professor C. C. De Silva, the medical fraternity, as well as the general public, should remember not just the “Godfather of Modern Sri Lankan Paediatrics,” but a unique intellectual whose fantastic brainpower was matched only by his relentless pursuit towards perfection.

To the world, he was a colossus of science. For me, he was a mentor who transformed a raw medical graduate into a disciplined scholar through a “baptism by fire”; indeed, a baptism that I shall cherish forever.

I do hope and pray that this narrative is a sufficiently adequate and descriptive tribute to a persona par excellence, a true titan of the Sri Lankan Medical Landscape.

From Scepticism to Admiration

Our first encounter in 1969 was, quite strangely and perhaps humorously, a lesson to me on my own youthful ignorance and audacity. As a fourth-year medical student, I watched a grey-haired gentleman in the front row challenge an erudite foreign guest lecturer with questions: queries which I considered to be “irrelevant”. I dismissed him then as a “spent old force”. On inquiry, I was told that the person was Professor C. C. De Silva, who had just retired. I quietly thought to myself, “Thank God for small mercies, as I would not be taught by someone like him.”

God forbid, too, as to how terribly wrong I was. Years later, I realised that those questions were the hallmark of a visionary and a dedicated pedagogic academic celebrity, intensely relevant to the health of the children of our beloved Motherland. They were totally and far above the head and intellect of a “raw” medical student. Thankfully, it was not long before, this dignitary, whom I had the bravado to call “a spent old force”, became one of the most influential and gravitational forces in my professional life.

The Seven-Fold Refinement

The true turning point came in 1971. Under the guidance of Dr M. C. J. Hunt, the Consultant Paediatrician at Lady Ridgeway Hospital, under whom I did the second six months of Pre-Registration Internship, I was forced by my “Boss”, terminology used at that time to describe the Consultants, to write my very first scientific paper on a very rare and esoteric condition. When it was submitted to the Ceylon Journal of Child Health, its Editor, Dr Stella De Silva, sent it to a reviewer for assessment. Impudently armed with my “masterpiece”, I jauntily presented myself at the residence of Emeritus Professor C. C. De Silva, who was allocated to be the reviewer of my creation.

What followed was a merciless masterclass in fantastic academic expertise. With a sharp mind and an even sharper red pen, Professor C. C. De Silva took my handiwork completely apart. He cut, chopped, and rearranged the text until barely a sentence of my original prose remained. Over several weeks, this “torture” was repeated no less than seven times. Each week, I would return with a retyped manuscript, only to have it bled dry, again and again, by his uncompromisingly erudite brain. It was indeed a “Baptism by fire“.

Yet for all this, there was absolute grace in his rigour. The man was so exacting in academic literary work that nothing, nothing at all, escaped his eagle’s eye. Each session ended with a delicious high tea served by his gracious wife, and the parting words: “My boy, you do have a lot to learn”.

By the eighth attempt, the paper that had originally been a raw, uncut nugget was finally polished into a veritable gem. The journal published it, and it was my very first scientific publication. However, much more importantly, it was the occasion when I learned the compelling truth of Rabindranath Tagore’s immortal words, “Where tireless striving stretches its arms towards perfection“. It clearly impressed on me the fact that for intellectuals like Professor C. C. De Silva, it was a compelling intonation.

An Unending Legacy

Professor C. C. De Silva was definitely much more than just an academic; he was the personification of British English at its finest and a scientist with an obsessive craving for detail. Later, he became a father figure to me, even attending my presentations and offering gentle constructive criticisms, which eventually moved yours truly from fearing it to desperately craving for it.

In 1987, in a final act of characteristic generosity, he asked for my Curriculum Vitae to nominate me for the Fellowship of the Royal College of Physicians of London, UK. I was just 40 years of age. Though the Great Leveller took him from us before his letter to the Royal College of Physicians could be posted, his belief in me was the ultimate validation of my academic progress.

The Good Professor left a heritage of refinement and scholastic brilliance that was hard to match. Following his demise in 1987, the Sri Lanka Paediatric Association, which later became the Sri Lanka College of Paediatricians, established an Annual Professor C. C. De Silva Memorial Oration. I was greatly honoured but profoundly humbled to be competitively selected to deliver that oration, not just once, but three times, in 1991, 1999, and 2008, on three different scientific technical topics based on my research endeavours. Those were three of the highest compliments that I have ever received in my professional life.

The Singular Man

Today, as we mark 122 years since his birth, the shadow of Professor C. C. De Silva still looms ever so large over the Lady Ridgeway Hospital for Children. He taught us that in medicine, “good enough” is never enough; it simply has to be the “best”. He was a caring and vibrant soul who demanded the best because he believed his students and his patients deserved nothing less.

I remain as one of a singularly fortunate cluster that had the extraordinary privilege of walking along a pathway lit by this great man. He was a fabulous leading torch-bearer who guided us in our professional lives. I was always that much richer for the time that I spent in his ever-so-valued company.

Emeritus Professor Cholmondeley Chalmers De Silva: My dear Sir, we will never forget you. This tribute is for a classy scholar, a superb mentor, a master craftsman, and most definitely, an extraordinary man like no other. Today, WE DEVOTEDLY SALUTE YOU and wish you HAPPY BIRTHDAY, in your heavenly abode.

by Dr B. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony. FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka.

Opinion

Why so unbuddhist?

Hardly a week goes by, when someone in this country does not preach to us about the great, long lasting and noble nature of the culture of the Sinhala Buddhist people. Some Sundays, it is a Catholic priest that sings the virtues of Buddhist culture. Some eminent university professor, not necessarily Buddhist, almost weekly in this newspaper, extols the superiority of Buddhist values in our society. Some 70 percent of the population in this society, at Census, claim that they are Buddhist in religion. They are all capped by that loud statement in dhammacakka pavattana sutta, commonly believed to have been spoken by the Buddha to his five colleagues, when all of them were seeking release from unsatisfactory state of being:

‘….jati pi dukkha jara pi dukkha maranam pi dukkham yam pi…. sankittena…. ‘

If birth (‘jati’) is a matter of sorrow, why celebrate birth? Not just about 2,600 years ago but today, in distant port city Colombo? Why gaba perahara to celebrate conception? Why do bhikkhu, most prominent in this community, celebrate their 75th birthday on a grand scale? A commentator reported that the Buddha said (…ayam antima jati natthi idani punabbhavo – this is my last birth and there shall be no rebirth). They should rather contemplate on jati pi dukkha and anicca (subject to change) and seek nibbana, as they invariably admonish their listeners (savaka) to do several times a week. (Incidentally, Buddhists acquire knowledge by listening to bhanaka. Hence savaka and bhanaka.) The incongruity of bhikkhu who preach jati pi duklkha and then go to celebrate their 65th birthday is thunderous.

For all this, we are one of the most violent societies in the world: during the first 15 days of this year (2026), there has been more one murder a day, and just yesterday (13 February) a youngish lawyer and his wife were gunned down as they shopped in the neighbourhood of the Headquarters of the army. In 2022, the government of this country declared to the rest of the world that it could not pay back debt it owed to the rest of the world, mostly because those that governed us plundered the wealth of the governed. For more than two decades now, it has been a public secret that politicians, bureaucrats, policemen and school teachers, in varying degrees of culpability, plunder the wealth of people in this country. We have that information on the authority of a former President of the Republic. Politicians who held the highest level of responsibility in government, all Buddhist, not only plundered the wealth of its citizens but also transferred that wealth overseas for exclusive use by themselves and their progeny and the temporary use of the host nation. So much for the admonition, ‘raja bhavatu dhammiko’ (may the king-rulers- be righteous). It is not uncommon for politicians anywhere to lie occasionally but ours speak the truth only more parsimoniously than they spend the wealth they plundered from the public. The language spoken in parliament is so foul (parusa vaca) that galleries are closed to the public lest school children adopt that ‘unparliamentary’ language, ironically spoken in parliament. If someone parses the spoken and written word in our society, there is every likelihood that he would find that rumour (pisuna vaca) is the currency of the realm. Radio, television and electronic media have only created massive markets for lies (musa vada), rumour (pisuna vaca), foul language (parusa vaca) and idle chatter (samppampalapa). To assure yourself that this is true, listen, if you can bear with it, newscasts on television, sit in the gallery of Parliament or even read some latterday novels. There generally was much beauty in what Wickremasinghe, Munidasa, Tennakone, G. B. Senanayake, Sarachchandra and Amarasekara wrote. All that beauty has been buried with them. A vile pidgin thrives.

Although the fatuous chatter of politicians about financial and educational hubs in this country have wafted away leaving a foul smell, it has not taken long for this society to graduate into a narcotics hub. In 1975, there was the occasional ganja user and he was a marginal figure who in the evenings, faded into the dusk. Fifty years later, narcotics users are kingpins of crime, financiers and close friends of leading politicians and otherwise shakers and movers. Distilleries are among the most profitable enterprises and leading tax payers and defaulters in the country (Tax default 8 billion rupees as of 2026). There was at least one distillery owner who was a leading politician and a powerful minister in a long ruling government. Politicians in public office recruited and maintained the loyalty to the party by issuing recruits lucrative bar licences. Alcoholic drinks (sura pana) are a libation offered freely to gods that hold sway over voters. There are innuendos that strong men, not wholly lay, are not immune from seeking pleasures in alcohol. It is well known that many celibate religious leaders wallow in comfort on intricately carved ebony or satin wood furniture, on uccasayana, mahasayana, wearing robes made of comforting silk. They do not quite observe the precept to avoid seeking excessive pleasures (kamasukhallikanuyogo). These simple rules of ethical behaviour laid down in panca sila are so commonly denied in the everyday life of Buddhists in this country, that one wonders what guides them in that arduous journey, in samsara. I heard on TV a senior bhikkhu say that bhikkhu sangha strives to raise persons disciplined by panca sila. Evidently, they have failed.

So, it transpires that there is one Buddhism in the books and another in practice. Inquiries into the Buddhist writings are mainly the work of historians and into religion in practice, the work of sociologists and anthropologists. Many books have been written and many, many more speeches (bana) delivered on the religion in the books. However, very, very little is known about the religion daily practised. Yes, there are a few books and papers written in English by cultural anthropologists. Perhaps we know more about yakku natanava, yakun natanava than we know about Buddhism is practised in this country. There was an event in Colombo where some archaeological findings, identified as dhatu (relics), were exhibited. Festivals of that nature and on a grander scale are a monthly regular feature of popular Buddhism. How do they fit in with the religion in the books? Or does that not matter? Never the twain shall meet.

by Usvatte-aratchi

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoWhy does the state threaten Its people with yet another anti-terror law?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoReconciliation, Mood of the Nation and the NPP Government

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoVictor Melder turns 90: Railwayman and bibliophile extraordinary

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoLOVEABLE BUT LETHAL: When four-legged stars remind us of a silent killer

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoVictor, the Friend of the Foreign Press

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoNew Zealand meet familiar opponents Pakistan at spin-friendly Premadasa

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoTariffs ruling is major blow to Trump’s second-term agenda

-

Latest News5 days ago

Latest News5 days agoECB push back at Pakistan ‘shadow-ban’ reports ahead of Hundred auction