Opinion

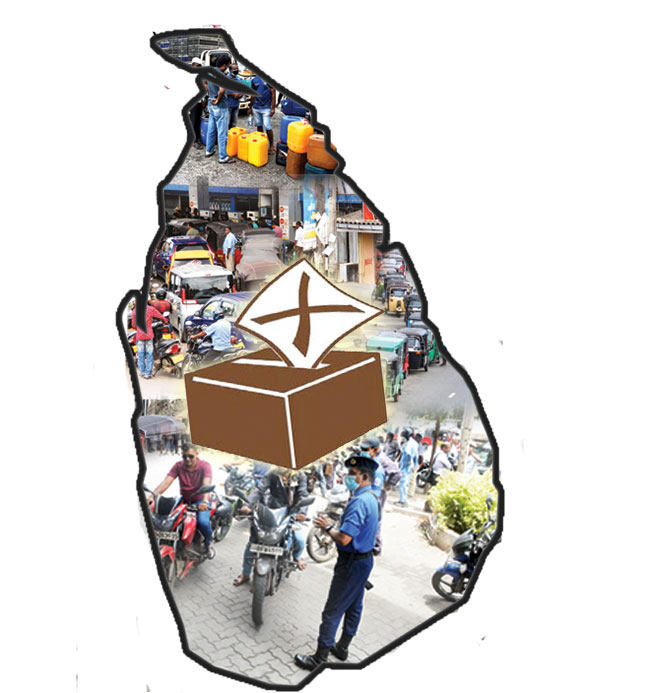

Electionsand economy

by Ram Manikkalingam

Director, Dialogue Advisory Group

Sri Lanka’s democracy is on a knife edge. When Gotabaya Rajapaksa fled his post, Ranil Wickremesinghe became acting president. And then he got officially elected to the post of President with the support of the Rajapaksas in parliament. Whatever our political views about Wickremesinghe, he did follow the proper parliamentary procedure to be legally constituted as president.

Some were even willing to go one step further. And say Ranil Wickremesinghe would adhere to democratic institutions and stabilise the economy. With the threat of parliament being attacked the very same day that Rajapaksa fled from office, some continuity in the political institutions and even personalities was not unwelcome to many Lankans. But Wickremesinghe’s efforts to meddle with the local government elections, risks putting paid to the very reason that may have made him a good choice for the presidency in turbulent times – belief in his adherence to Sri Lanka’s democratic institutions and his ability to manage the economy.

The delay in local government polls risks inciting the very instability the Wickremesinghe presidency was supposed to end, weakening our democratic institutions and putting the economy at risk. There are no moral or legal reasons for delaying the elections. However, we do hear pecuniary and political ones. The government claims they do not have funds to hold elections. But it managed to find money to hold an Independence Day tamasha that nobody wanted. While the price of the Independence parade is less than what the local government elections will cost, it is still a sign that money can be found when the government gives it priority.

Not holding elections because we have no money can very well lead to a slippery slope. Let us say we are still bankrupt in December 2024. Would the President then say that since we do not have funds, we cannot hold a Presidential election? Or worse, does this lead to perverse incentives: those in power would have an incentive to keep Sri Lanka bankrupt so that they can continue to delay presidential and parliamentary elections, if they risk losing!

Granted that local government elections are not parliamentary or presidential elections. And it is quite possible that the government is sincere in its belief that this is a minor postponement. And once the IMF provides credit and the economy turns around, the elections can be held. Unfortunately for the government, this is not how the opposition political parties see it. Indeed, most Lankans are sceptical about the government’s rationale for the delay in local elections. They believe the government is delaying elections on spurious grounds because of the delay in getting approval for the IMF package.

President Ranil Wickremesinghe is risking both the political and economic stability of the country by delaying these elections. Except for some determined protesters who have continued unabated, the protests have died down over the past few months. The reasons are many – from fatigue and the daily struggles that people are going through, to the sense that this government must be given the time to sort things out. A delay in elections risks re-igniting the protesters who will join with the opposition political parties to oppose the government. Depending on how effective these protests are, the government will be faced with two options. Permit the protests to grow and risk being thrown out of office, or crackdown and risk bloodshed, and still be thrown out of office.

Even if a crackdown leads to the protesters giving up, the climate it creates will be far from conducive to economic reform, foreign investment and a regeneration of the economy. This, in turn, can undermine the Wickremesinghe government’s efforts to rebuild the economy. While the IMF only looks at economic indices in making decisions about lending, the governments on the IMF’s board may not do so. They will have to explain to their citizens why they are throwing good money after bad, by approving loans for a government that is cracking down on its own people and enabling the very politicians responsible for the collapse of the economy to continue to run the country.

Ranil Wickremesinghe should hold the local government elections, safe in the knowledge that his party and that of his current coalition allies – the Rajapaksas – will lose. Rather than rue this loss, he should welcome and trumpet it as a reflection of Sri Lanka’s political durability and continuity. If the opposition does very well – as it is likely to – he should dissolve parliament and call for early elections. Again, safe in the knowledge that these elections will lead to the defeat of the Rajapaksas.

President Wickremesinghe can then claim credit for ushering in an orderly democratic transition and economic stability, rather than a disorderly one that undermines the economy. He will of course have to govern together with a messy political alliance that is likely to consist of some combination of the Samagi Jana Balawegaya, the JVP, and Tamil and Muslim parties, with all the challenges such a setup entails. But these challenges will at least have the excuse of being in the service of a decent democracy and a better economy.

Opinion

Economic value of Mahinda Rajapaksa

by Dr Sirimewan Dharmaratne,

former Senior Analyst, HMRC, UK.

Although this may not be doable at all times, it is possible to retrospectively assess the economic impact of crucial decisions. While putting a value on a person may seem unethical or unconscionable, everyone has an economic value. Our lives are valued for myriad of commercial purposes, such as for insurance policies, compensation for work place injuries and death and for various illnesses due to environmental pollution and other such instances. In all these cases, what is valued is the economic life, and not the intrinsic value of the person itself.

The method is ‘what if’ concept; how much could he/she have earned if the person has not died or been incapacitated? The same concept could be extended to assess the value of critical events, such as natural disasters. The method simply is to compare the state before and after the even and put some economic value to the event or the decisionmaker.

Benefits of Mahinda Rajapaksa (MR)

The most seminal event that happened in Sri Lanka during MR regime was ending the war on terrorism in 2009. Friends and foes alike attribute this historic event to MR. Although there are different schools of thoughts on this, winning or to losing a war is ultimately attributed the leadership and not to anyone else. This is because it is the leader that takes decisions and accept all risks. Winston Churchill as the war-winning UK prime minister, Chinese revolution has been attributed to Mao Tse-Tung, and the ending the civil war in the USA has been attributed to Abraham Lincoln. The ensuing discussion and analysis are based on this premise.

Benefits of Ending the War

There is no doubt that there was significant economic revival after the end of the war. The underlying justification is that if he had not taken the decision to end the war, it would not have ended in 2009. As such, whatever the costs and benefits of ending the war can be attributed to MR. While a complicated economic evaluation is not possible within the context of this article, it is possible to see whether we have enough evidence to do a ‘back of the envelop’ economic assessment of ending the war.

Revival of Tourism

One of the unequivocal benefits of ending the war is the massive revival in tourism as seen in tourism statistics. The average tourism spending during the 5-year period before 2009 was about US$ 0.76 billion a year and during the 5-year period after the war was over US$ 2 billion a year. Therefore, the increase of revenue of around US$1.25 bn a year can be safely be attributed to the event of ending the war as this was the only pivotal event that happened in 2009. Assuming that 30% of these spending is net profit, then nearly US$ 2bn was accrued to Sri Lankan businesses during this 5-year period immediately after the war compared to the previous 5 years.

Economic Growth

There was nearly a 5% jump in the GDP growth in the year after the war. That momentum was maintained for the next two years. During the first three years over $16 bn was added to the economy compared to the $8 bn during the three preceding years. Unemployment that was well over 5% in 2009 (and in preceding years) dropped below 5% in 2010, for the first time since early 1990s. On the average unemployment fell by 0.34% year during the 5 years after 2009. No doubt other economic indicators showed similar positive trends.

Other Benefits

It is commonly believed that egregious corruption and irregularities were rife under the guise of war for many years, under all regimes during the 30-year period. These essentially ended after 2009. Then there are other benefits such as improved international relationships, more investments, building of several roads and highways and the general wellbeing of the citizen, which are all hard to quantify in this context. Although, this momentum in growth could not be maintained for a longer period due to regime changes, cronyism, complacency, capricious decision-making, and many other factors, they cannot unfortunately be quantified. While these unconscionable acts may or may not be directly attributed to MR, his cavalier attitude in some instances may have contributed to gratuitous corruption under his watch. Due to these reasons, a vast stream of benefits that could have resulted from the end of war never materialised.

Costs of Mahinda Rajapaksa

There are economic costs and financial costs. Financial costs are those borne by the taxpayer for his upkeep and benefit. These are the costs that are the focus of the ongoing controversy. Economic costs are the costs to the taxpayer arising from decisions that he may have taken. It is important to note that such decisions must have been approved by the parliament and therefore, any responsibility should be held collectively. Nevertheless, for this article we will assume that they are taken unilaterally and exclusively attributed to MR.

Two of the main projects that are constantly being flaunted are the Hambanthota port and the Mattala airport. Both these are portrayed as colossal waste of money. There is ample evidence that these main projects and others were undertaken without much thought. However, as far as this article is concerned, only the losses to the taxpayer resulting from these decisions are considered.

Large infrastructure projects yield benefits far in to the future as they have a very long lifespan. Further, their investments cost is not a loss, but only the losses incurred in their operation. Although, initially made significant losses due to lack of business, with the deal agreed with a Chinese investor in 2016, it appears that the port is no longer costing the taxpayer. In fact, there is already evidence that it could be profitable with the proposed oil refinery. Also, with the opening of the economy for imports, this could be a major trade hub. Therefore, for the purpose of this article, it is reasonable to use the widely quoted loss of US$216 million during the period of 2011-2016.

The Mattala airport on the other hand has incurred about US$140 million loss during the 5-year period of 2017-2022. There is still no evidence that it could be turned into a profit-making venture. There may be other smaller projects that could have made lesser losses. To account for all those, a rather ballpark figure of US$500 million sounds reasonable at least for the purpose of this exercise.

Financial Costs

The main contentious issue at the moment is whether the facilities (particularly the accommodation) at the disposal of MR is justified. Let’s say this current facility is available to MR for a 20-year period from 2015 and the monthly average imputed rent is Rs 20 million a month. Then the total cost to the taxpayer would be about US$16 million. Adding all other benefits that he is entitled to, a figure of US$ 50 million seems to be a reasonable assessment of the as the total cost of maintaining MR for a 20-year period from 2015.

Stolen Money

The main accusation of MR is not the few bad policy decisions that he may have taken or the cost of his retirement, but the colossal amount of money that he claimed to have stolen and stashed overseas. Despite years of accusations, the existence or the amount of this money is yet to be unambiguously ascertained. Unfortunately, there is no paper trail or digital footprint to show that taxpayer money has been siphoned out of the country. There is a further twist to these claims of stolen money. They are only relevant for this analysis, if taxpayer money (from the Treasury, for example) was taken out of the country. On the other hand, gratuitous payments directly deposited in foreign banks (commonly known as commissions) for awarding contracts are irrelevant as far as the taxpayer is concerned. This would only be an issue if the taxpayer was short-changed as a result of awarding contracts. Either way as far as stolen money is concerned, until definitive proof is surfaced, imaginary amounts cannot be taken into account.

Is he worth it?

The total loss to the taxpayer during the MR regime plus is subsequent maintenance costs for a 20-year period from 2015 comes to about US$ 0.5bn. It is important to note that the maintenance cost is only a fraction of the total economic loss due to the two main projects. Based on a very conservative estimate, net benefits from the revival of tourism alone could be nearing US$ 2bn for the 5-year period after ending the war. Then there are all other benefits resulting from accelerated economic growth in the immediate few years after 2009. Therefore, for MR to be a liability to the taxpayer someone will have to find at least US$2 billion of taxpayer money stashed somewhere. While this search is going on, it seems that MR has every right to stay put where he is now, purely from an economic view point.

This perfunctory analysis portrays how even in an extreme situation some objectivity can be imparted to the decision-making process. With some rudimentary information, decisions can be made more objective. Also, a nascent idea could be vastly improved by seeking and including actual data rather than hearsay. For example, the ‘analysis’ presented here could be immensely improved by adding factual information. This is a process that any government should introduce as a matter of principal in all decision making.

Opinion

China’s meteoric rise through strict policy implementation!

The obscure Hangzhou hedge fund that coded a ChatGPT competitor as a side project it claims cost just $6m emerges from a concerted effort to invest in future generations of technology.

This is not an accident. This is policy.

The raw materials of artificial intelligence (AI) are microchips, science PhDs and data. On the latter two, China might be ahead already.

Really speaking, Western World had been caught napping through its lethargy while enjoying much higher standards of living!

Here in U.K., the Welfare State including the NHS and Social Services made some people opting not to work, claiming all manner of benefits! It is a common sight to see able bodied men and women selling The Big Issue magazine in street corners!

There are on average more than 6,000 PhDs in STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) coming out of Chinese universities every month. In the US it is more like 2,000-3,000, in the UK it is 1,500.

In terms of patents generally, more are being filed in China than in the rest of the world put together. In 2023 China filed 1.7 million patents, against 600,000 in the US. Two decades earlier China had a third of the patents filed by the US, a quarter of Japan’s and was well behind South Korea and Europe!

While there are some questions about the quality, on some measures China now exceeds the US on what is known as “citation-weighted” patents too, which adjusts for how often new scientific papers are referred to.

Chinese lithium-ion electric batteries now cost per kWh about a seventh of what they cost a decade ago. DeepSeek is doing in AI exactly what China has done elsewhere.

While the impact of this was most visible in electric vehicles (EVs), where China is now the world’s biggest exporter, having cornered the supply chains and the science for battery technology, it stretches well beyond. BYD Auto Co., Ltd. and brand of BYD (Beyond Your Dreams, publicly listed Chinese multinational Manufacturing Company. It manufactures passenger Battery Energy Electric Vehicles (BEEVs) and Plug-in Electric Vehicle (PHEVs), in China. It also produces electric buses and trucks. The company sells its vehicles under the main BYD brand and high-end vehicles under its Denza, Yangwang and Fangchengbao brands.

Even in auto the Chinese manufacturers are now pushing the concept of “electric intelligent vehicles”, in which conventional carmakers cannot compete, especially on software development.

China’s consumer electronics companies are shifting into car manufacturing, with “dark factories” operated 24/7 by armies of AI-powered robots, now also increasingly made in China.

This innovation is partly of necessity. China does not have indigenous fossil fuels, and is electrifying at an astonishing rate, and is referred to by some researchers as an “electro state”. It now files three-quarters of all clean tech patents, versus a twentieth at the start of the century.

Last year the US National Science Board asserted China’s objective of being the world’s leading science and engineering nation was on the verge of being achieved. “We already see this in artificial intelligence, where China out publishes us, has more patents, and produces more students than the United States,” they wrote.

Delegates who accompanied the UK Chancellor Rachel Reeves to China earlier this month marvelled at how the Beijing air had been cleaned up, and indigenous electric cars were everywhere. Another UK CEO told the media of a visit to Huawei’s Oxbridge-style campus complete with spires and bridges, and its own Tube line, purely for its scientists.

Clearly, however, there are concerns about censorship, democracy and security. One of the drivers of the Chinese AI industry has been access to extraordinary amounts of data, which is more difficult to get hold of in the West.

If the US Congress was sufficiently concerned about TikTok to ban it, then surely a table-topping AI program could be highly problematic. President Trump’s argument recently was that DeepSeek’s innovation was “positive” and “a wake-up call”. China has not been prominent as the first target of Trump tariffs.

There is still an obvious balancing act for the UK government here. But this sort of innovation and its impact on the world was exactly why the chancellor visited Beijing a fortnight ago.

She said at the time she wanted a long-term relationship with China that is “squarely in our national interest” with the visit part of a “commitment to explore deeper economic co-operation” between Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer and President Xi.

Other European nations such as Spain have encouraged China not just to set up factories but to transfer its advanced battery technology, for example, into Europe.

The West wants China to make its T-shirts, its tables, its TVs and EVs. But could that really now stretch into DeepSeek data-hungry AI models too? It is a deep tremor, not just for tech, but for economics and geopolitics as well. Do not be fooled into thinking that China is a benevolent country when it offers “help” with massive projects in third world countries as they all come with strings attached and possibly expansionist agendas!

Sunil Dharmabandhu

Wales, UK

Opinion

A singular modern Lankan mentor – Part III

by Laleen Jayamanne and Namika Raby

Gananath Obeysekere: In search of Buddhist conscience

(Baudha Hurdasakshiya Soya)

(Part II of this article appeared in The Island on Monday – 03)

Tissa Ranasinghe’s and Gananath’s Kannagi

Gananath’s Pattini book has a mysterious blue-black cover with an icon of Kannagi in Bronze sculpted by Lanka’s foremost Modernist sculptor Tissa Ranasinghe, commissioned by Gananath. What Appadurai termed Lanka’s links with ‘Indic culture’ is encapsulated in this image of the heroic figure Kannagi from the Tamil epic, striking a gesture of mourning for her husband Kovalan, unjustly killed by the king of Madurai. She kneels with her arms held raised around her head in the familiar triangular formation suggestive of the aniconic representation of the Yoni (an emblematic civilisational gesture of great iconic strength and power, in the Bronze lineage of India, which stretches back to the little bronze figurine of The Dancing Girl of Monhenjodaro itself), even as she laments the injustice. And those of us who know the legend also see that her left breast is missing. Kannagi, it is told, tore her breast and hurled it at the city of Madurai, setting it on fire with her righteous anger! Together, Gananath and Tissa have presented Kannagi in a most generative posture and gesture for the cover of the book on the Sinhala Pattini cult, the only Mother goddess of the Sinhala folk, borrowed from the Tamil Epic, to assuage and heal Sinhala male sexual anxieties and group trauma. This marvelous collaboration between Lanka’s celebrated Modernist Sculptor and Anthropologist was a multivalent, therapeutic intervention into Lanka’s cyclical interethnic violence. The book was published in 1984, one year after the state sponsored pogram against Tamils in July ‘83. Tissa’s modernist Kannagi demonstrates how an archaic ‘Maternal Archetype’ can be creatively mobilised by an artist, to express contemporary predicaments without diluting her orginal power and affective vitality magnified by the use of bronze, a resonant civilisational material.

Pattini is the Sinhala Buddhist incarnation of the Tamil heroic Kannagi and as far as I can tell she appears not to have the iconographic attributes of heroic rage and righteous anger which Kannagi embodies in the Tamil Epic. Kannagi is the step mother of Manimekalai who became a Buddhist nun, according to legend. Is it the case that Pattini is without progeny and so, as a Mother Goddess, rather like the West Asian mother Goddesses who were also virgins? As a girl, my mother and I were devoted to rituals of Mother Mary (mother of Jesus), also known as the Virgin-Mary from, let’s not forget, West Asia (in historic Palestine).

Professor Sunil Ariyaratne’s 2016 film Pattini, warrants a passing comment or two in this context as an example of the institutional consolidation of Neo-Liberal capitalist extraction and commodification of the residual vitality and power of the perennial syncretic Folk traditions of Lanka. It is a neo-traditionalist extravaganza in the genre of nostalgic revival of ‘the Sinhala-Buddhist Folk Heritage of Lanka’ which flourished recently with much fanfare and state patronage as a ‘Rajapaksha genre’. The film deals with the Kannagi legend just so as to reduce it to reinforcing the Sinhala-Buddhist ideology of purity and virginity for women through the exemplary tale of ‘the pure wife’ Kannagi and her step-daughter Manimekala, who becomes a Tamil Buddhist. Her dearest wish is to be reborn as a male so that she can indeed aspire to become a Buddha. The emphasis is on the preservation of virginity (Pathiwatha), and the enthroning of male sexuality as the route to attaining Buddhahood. The mythic epic figure of Kannagi who in her rage enacts heroic justice in the Tamil epic is converted into a parabolic emblem of virginal purity.

A Humanist Education

Gananath’s education is a strand very comprehensively covered in the film, a source of his immense openness to the world of ideas and refusal to accept them on authority without critical evaluation. The film opens at Gananath’s home in Kandy which he shares with Professor Ranjini Obeysekere who appears with her vibrant intellect and grace and ends there too. The couple are shown warmly welcoming the film crew to their house as they have done over their long engagement with numerous students, as they did with me both in Kandy and the US when I was tangled up and blue. It is worth remembering here that Ranjini is the Editor in Chief of the magnificent multi-volume translation project of the Jataka Tales into English, published just last year. It is only now that I can see how deeply Ranjini and Gananath’s scholarship is in conversation with each other.

The account of Ranjini and Gananath’s meeting at Peradeniya University while studying English Literature with Professor E.F.C. Ludowyk is one of the highlights of the film for me. Ranjini acted in the plays directed by Ludowyck and they studied English Literature at honours level together. Interestingly, though Gananath followed the Dram Soc activities on campus, he didn’t participate in any of them, his interest being elsewhere. He says, whenever he could he got onto a bus or train and travelled to distant villages to talk to villagers and monks and tape their songs (kavi). Gananath says that Ludowyck was the best teacher he has ever met and that he was responsible for directing him at every key juncture of his undergraduate life and soon after when making the unusual choice of going to a US graduate school, refusing a scholarship to Cambridge because of colonial history. Gananath’s brilliant textual analysis and exegesis of texts in Sinhala of myths and legends, especially the complex corpus of the Gajabahu legend, owes a great deal to the textual training he received from Ludowyck in ‘Practical Criticism’. We are all beneficiaries of this tradition of Literary Criticism which was part of the training we received in English Lit in old Ceylon and now continued by scholars such as Professor of English, Sumathy Sivamohan and others. Ranjini tells us that it was Ludowyck who collected Rs 10,000 from ten of his friends and handed it to Gananath to go travel the country and do what he wished soon after he graduated with English Honours. All he was asked to do was to write and thank his benefactors. So, it’s this tradition of mentorship and duty of care that Gananath and Ranjini have practiced with their own students during their long working life at American Universities.

A Counter Archive of a People’s Literature, Painting and Ritual

Though I was familiar with some of Gananath’s writing and studied a couple for the film I made, there is a major topic of his research which I didn’t know anything about and as such this film has provided an important learning experience for me. In drawing from the local non-canonical texts preserved in Temples, libraries and archives, which are written, in Sinhala by the folk and as such are anonymous, not by scholar monks in Pali, the language of high learning, Gananath has been able to piece together stories, legends of migrations from India, Kerala and Tamil Nadu and the ways in which some of these waves of migrants have been incorporated into the folk Buddhist body politic and culture. The gist of which is the seemingly heretical idea (an affront to Sinhala exceptionalism and their sense of manifest destiny as ‘pure Ariya’ Sinhala-Buddhists claiming to be the only real Lankans), that at one time, all people who call themselves Sinhala in Lanka did come from India and were indigenised through various practices and this happened in waves of migration over long periods of time. This section draws from the folk archive of poetry, ritual and Temple murals and legends such as the complex Gajabahu Myth, that bear witness to these processes of migration and acculturation, to make the case for the existence of robust muti-ethnic, diverse communities dotting the island. The legendary folk tales and rituals were, he says, imaginative, fictionalised, poetic expressions of folk memory of these migratory events, not ‘false’ accounts.

Here I want to cite a longish relevant passage from Professor Patrick Olivelle’s highly acclaimed book, Ashoka: Portrait of a Philosopher King. Ramchandra Guha, the editor of the series called ‘Indian Lives‘ of which this is the first, says of the Lankan Olivelle that, ‘he is one of the greatest living scholars of Ancient India’. Here’s Olivelle’s argument, on the familiar opposition between History and Legend, which supports Gananath’s theoretical move with practical consequences for how we understand ourselves as Lankans.

“In a seminal remark, the historian Robert Lingat notes: ‘There are two Ashokas—the historical Ashoka whom we know through his inscriptions, and the legendary Ashoka, who is known to us through texts of diverse origin, Pali, Sanskrit, Chinese and Tibetan. Although essentially correct, there are two problems with Lingat’s assessment.

First it is simplistic to contrast the ‘historical with the legendary’. The portrait of Ashoka I have constructed in this book is based on Ashokan inscriptions and artefacts, yet it contains a heavy dose of interpretation, translation, imagination, narrative, perhaps bias… The ‘legendery’ is not simply false and to be dismissed; it is the reimagination of the past to serve present needs, something inherently human. These narratives were meaningful and important to the persons and communities that constructed them. Their purpose was not to do history in the modern sense of the term, but to do something much more significant to them in their own time.

….There are actually not two but several Ashokas, including modern ones”.

Following this argument, we Lankans who try to practice ‘Loving-Kindness’ must be thankful that Gananath has highlighted for us at least two Dutthagaminies, in his timely essay, Dutthagamini and the Buddhist Conscience, written in the wake of the carnage of the ‘July ‘83’ state sponsored pogrom against the Tamil people of Lanka. There is the familiar Dutthagamini, taught to us in school, as a Sinhala-Buddhist, Tamil-hating ethno-nationalist, constructed from the Mahavamsa narrative taken as incontrovertible historical fact. On the other hand, Gananath presents evidence, from the Dambulla temple paintings, for a humanist Dutthagamini, who like Ashoka himself, was contrite about the mass slaughter he conducted and his killing of Elara the Tamil king.

The film shows us how Gananath makes a radical scholarly move in the late stages of his life by researching the indigenous folk of Lanka, the Veddhas. He argues against the deep-seated idea, promulgated by the ethno-nationalist Sinhala-Buddhist ideologues, that there is an ancient historical enmity between the Sinhala and Tamil folk of Lanka going back to the days of the kings, prior to colonialism. Gananath analyses the myth of origin of the Sinhala folk as represented in temple murals that show Vijaya’s arrival in Lanka from India and his marriage with the indigenous woman Kuveni. The Veddhas are the descendants, he says, of Kuveni and her children by Vijaya and are the ‘other’ or outsider, so to speak, to the Sinhala.

Through his ethnographic work on the powerful Vadi procession (perahera) in Mahiyanganaya, Gananath is able to show the ritual means through which they are incorporated into the Sinhala community. The ethnographic film, demonstrating this robust festive ritual event of staging cultural difference and incorporation, supports Gananath’s argument that the Veddas have been the true ‘outsiders’ of the Buddhist polity (in dress, culinary habits, religion), and despite that, the Buddhist culture had ritual mechanisms of incorporation of the outsider, without resorting to slaughter, while also acknowledging and respecting the awesome power of the Veddas. This section should be shown to school kids, I think, because of its liveliness and pedagogic value. Gananath acknowledges the fine scholarship of Paul E. Peiris on the Veddas and shows the colonial hostility and violence towards these indigenous folk of Lanka. Gananath’s ‘Cook Book’, also relevant to Australia’s colonial history, would have provided a global perspective on colonisation of indigenous peoples and the violent means used in casting them as ‘uncivilised primitives’, which in turn would have prepared him well to write the book on, the Veddas, Creation of the Hunter, in 2022.

What to Do, Napuru Kaleta? (In Wicked Times)

It seems to me that young scholars and artists might be able to generate a new thought or two by reading Gananath’s essays and books in relation to Ananda Coomaraswamy’s Mediaeval Sinhalaese Art (Campden: Gloucestershire, 1908) and Olivelle’s book on Ashoka. In this way, the monodisciplinary compartmentalisation of knowledge, ideas, can be disturbed so as to gain aesthetic nourishment to create, with what’s left, after the ravages of Neoliberal cultural nationalism’s cognitive extraction of our brains. All three distinguished, visionary Lankan scholars were writing about times when material culture and the ‘Intangible Heritage’ (A UNESCO Platform for their preservation) of Lanka and India were/are being destroyed from within, extinguished.

Some ‘transversal’ or lateral ways of understanding and connecting material practices/stuff and immaterial ideas are called for now, I believe, and these three Lankan scholars have shown us many ways in which this can be done. Let me clinch my argument by citing the full title of Coomaraswamy’s indispensable book which took 60 years to be translated into Sinhala. Professor Sarath Chandrajeewa (who also taught ‘mati-weda’) gave me this information for which I am most thankful. I read it in English as an undergraduate, quite by chance. Here’s the extended title:

“Being a Monograph on Mediaeval Sinhalese Arts and Crafts, Mainly as Surviving in the 18th Century with an Account of the Structure of Society and the Status of the Craftsman.”

Gananath might well have known through Ludowyk that the first edition of this book was hand printed in England by Coomaraswamy himself over a period of 15 months on the same printing press (which he purchased), as the one in which the first edition of the complete works of the Mediaeval English poet Chaucer was printed by William Morris, one of leaders of the ‘Arts and Craft Movement’. There is a wonderful story I heard from a native informant of California, of Gananath’s freshman lecture at the University of California in San Diego, on Pilgrimages. On hearing Gananath recite an entire section from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales ‘by heart,’ the students gave him a standing ovation!

Felix Guattari’s Three Ecologies, (namely Social Ecology, Mental Ecology, Environmental Ecology), is another a book worth reading (now freely downloadable), alongside the others as he was a radical psychotherapist trained in psychoanalysis by Lacan, and a Left Activist in France who also collaborated with the philosopher Gilles Deleuze on Anti–Oedipus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia (1968), which was a best seller. He also worked at a humane, innovative mental health institution which was part of the radical anti-psychiatry movement of the 60s and was a wild thinker who reminds me of Gananath and also had the requisite discipline, like him, to write books that crossed generations. He died all too soon, but Gananath will turn 95 on the second of February 2025.

Finally, my gratitude to the producers of this film, the Kathika Collective whose independent spirit, deep research, dedication, and not least, the love of cinema has led to the production of this film over a long period of time, which included the hiatus of the COVID pandemic. While Dimuthu is credited as researcher, script writer and director and Chathura Madhusanka with editing and camera, a great many well wishes (acknowledged in the credits), contributed freely to this film which has not received any external funding. The spirit of education that drove this film is a truly beautiful tribute to Gananath and Ranjini Obeysekere, our indispensable mentors, both.

Yahonis Pattini Kapumahattya’s haunting voice emanating from a deep folk history (which Gananath much admired and we are privileged to hear), accompanies the long credit list.

The film is dedicated:

“To all rural folk who in their diverse ways enriched the peasant Buddhist tradition and found Buddha in that”. (Concluded)

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoNew Bangalore-Jaffna flights in the works

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoCID questions top official over releasing of 323 containers

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoCardinal says ‘dark forces’ behind Easter bombs will soon be exposed

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoHRCL reports on Rohingya asylum seekers

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoA singular modern Lankan mentor – Part II

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoBharath Rang Mahothsav Parallel Festival in Colombo

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoIshadi Amanda makes history as First Runner-Up at 40th Mrs. World Pageant

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with EcoMatcher to launch transparent, tech-driven tree planting in Sri Lanka