Features

Compensating a ‘parlour’ owner in Cambodia

by Jayantha Perera

I joined the ADB in Manila in November 2002. The highlight of the new job as a social safeguard specialist was the opportunity to visit and study projects in Asian countries. In 2003, I visited Cambodia to check whether the physically displaced persons of an ADB-funded highway project had received fair compensation for their lost property and adequate assistance to restore and improve their affected livelihoods and income sources.

The Travel Branch of the ADB secured an official Cambodian visa and a business-class air ticket for me. I expected to travel without any hindrance. At the Bangkok airport, my self-image as an international civil servant was smashed when a Thai Airways officer refused to board me because Cambodian authorities had not informed the airline about my arrival. The visa and the exchange of official letters between the ADB and the Government of Cambodia regarding my mission should have facilitated my travel. The airline counter officer called Phnom Penh to check whether I was on the list of arrivals for the evening Thai flight. After ten minutes, the officer issued my boarding pass.

Just before landing in Phnom Penh, I saw the vast floodplain. It stretched from the banks of the Mekong River to the outer edges of the expansive valley. The setting sun with many clouds created patterns of fantastic colours across the sky. I thought about the highway I would visit soon and wanted to see it from afar. I could not find it, but I saw a wide road with several overpasses under construction. I thought that was the highway that I was going to visit.

At the Phnom Penh airport, two uniformed officials stopped me. They grabbed my passport before I arrived at the immigration counter. They did not speak English but beckoned me to follow them to a large room. They went behind a large desk and ruffled through my passport as if looking for a hidden treasure or contraband. One of them scrutinized the Cambodian visa page. Then, both studied it together for another ten minutes. They waved at me to follow them to another room.

An old officer with more stars on his uniform lapel sat behind a vast, ornate table with a giant old computer. The two who accompanied me saluted the old man and said something loudly. The boss listened carefully and smiled. He asked me in English where I was going and whether I was an ADB staff member. Then he waited a few minutes, stamped my passport, and told me, “You can go now.” The two officials looked sad, as if they did not want to part with me.

When I exited the airport, a uniformed young man was waiting for me with my name on a piece of cardboard. He did not speak English, but I trusted him to take me to the hotel that the ADB had booked for me. The evening was pleasant soon after a light shower. I could see and feel the heat emanating from the newly tarred road in front of the hotel. I wanted to go out for a walk but was scared that another uniformed person might stop me to interrogate me. I found refuge in my comfortable hotel room.

I met with the project international resettlement consultant at the hotel in the morning. As a British citizen who had lived in Cambodia for a decade, he brought a wealth of experience and understanding of the local context to our discussions. Together, we identified a few locations on a map to visit in the morning. At the first location, we met about 10 persons. Each had lost a narrow strip of land from their front yards to the highway. They still lived on their shrunken property. They complained that they had not received adequate compensation for the acquired property.

The project had not improved or at least restored their lost livelihoods. Many were fruit and vegetable sellers with stalls in their front gardens close to the road. After the road widening, no driver stopped at their fruit and vegetable stalls to buy. Vehicles moved very fast, and there were no kerbs where a car could park safely to purchase local products. The resettlement planners of the project, too, had apparently ignored the loss of income of the fruit and vegetable sellers.

The consultant took me to a small bazaar on the highway. I walked around and saw a new building. Its front door was closed, but several persons were standing before it. I walked to them with the translator and asked them whether they, too, had lost land. A man in a short-sleeved red shirt and white trousers smiled and introduced himself as the building owner. He spoke English haltingly. He invited us in and opened a few windows. The furniture smelled musty. He shouted at a young man, and in a few minutes, the young man brought us herbal tea. While sipping tea, the owner studied us without talking. Once we all drank tea, he rubbed his palms and smiled again.

“Are you from the World Bank?” the owner inquired.

“No. We are from the ADB,” I replied.

“Good. I wanted to talk to you,” the owner said.

He took time to discuss his issues, was apologetic, and gave the impression that he was reluctant to divulge some information or that some problems bothered him.

I asked him, Did you lose any land to the highway?

Yes, I lost a strip of land to the road, and as a result, I had to rebuild the facade of the building, he complained.

“Did you get money for the land taken?” I asked.

“Yes, the company paid me. But not enough money. The land by the highway is precious. I spent more money to rebuild the facade of the building. He hesitated again and smiled. I waited for him to collect his thoughts.

Suddenly, he said, “I had a popular parlour here, and 20 women worked for me.” His voice lowered, and he seemed to be struggling with his emotions. He muttered something, and then, visibly emotional, he began to cry. I waited, understanding the depth of his experience.

Finally, he said, “I didn’t receive any compensation for losing my livelihood and those 20 young women. They were good girls from nearby villages. Customers praised their service.” Despite the challenges, the owner’s resilience was genuinely inspiring.

Did anyone visit you before the construction of the highway started? I asked.

“Several surveyors visited me and collected information about my land.”

Did you tell them about the parlour and the girls?

The town officer was with the surveyors. He knew about the parlour. He criticized me for running an unlicensed brothel in front of the surveyors. But I had paid the town officers monthly for running the parlour.

Do you still run the parlour? the consultant queried.

“How can I? The town office threatened to acquire the whole building if I restarted the business,” he retorted. Then he continued, “I was born in Vietnam but moved to Cambodia when I was young. I knew some American soldiers, and I learned English from them. My father left this land to me. I did various odd jobs and earned money to start the parlour. First, I brought in three young village women and paid them well. They were happy, and they still wanted to be with me. I treated them as my sisters. I protected them from nasty gangs who kidnapped women to smuggle out of the country.”

He paused for a while and got into a reflective mood. We all waited. Because I treated the three women well, they offered to bring their friends to my parlour. I was very reasonable with all of them. I paid them weekly and provided free food and lodging. For ordinary services such as body massages and head rubs, I charged only five dollars. If a man wanted to stay longer, I charged 10 dollars and the food cost. Some village girls offered their services part-time to earn a little extra money. One girl wanted to earn money for her wedding. When all of them were with me, this large house was full of fun, food, and company.”

Where are those girls now I inquired.

The parlour owner explained, “Most of them returned to their villages. About six brave women stayed with me to serve clients from the bazaar. You know their job is precarious, as most clients are truck drivers and strangers. Some have tried to take women from the bazaar to unknown places.

He said in a sad tone, Women chose to stay with me because I know most of the men at the bazaar. The women love me. When the women were with me, a doctor checked them every month for infectious diseases. I provided free condoms and told my clients that they should wear condoms if they wanted services other than massage. There were a few instances when clients refused to wear condoms. I intervened and sent them off after refunding them.”

I heard recently that three women disappeared from the bazaar. They were not my women. Someone told me that the Police had picked them up and taken them away. I don’t know what happened. The Police continued to visit me, and the town officer threatened the building would be acquired soon because of its bad reputation.”

He smiled and told me that the Police and town officers were unhappy because some could not get free services anymore. Some of them blamed me for the collapse of the parlour. With 20 women, two full-time cooks and four waiters lost their employment. They did not get any compensation for losing their livelihood. The project authorities did not treat them as project-affected persons because they worked at the parlour.

I inquired about the women who had gone back to their villages. He did not know what happened to them, but he was sure they were unemployed. Their families depended on the money they had earned at the parlour. He got pensive again and waited a few minutes as if worried about their fate. He inquired whether the women could get compensation because they had lost their employment. I told him they should get compensation and at least some training in income generation.

The ADB’s Involuntary Resettlement Policy views a displaced person’s employment from an economic, not an ethical, point of view. The parlour business was not considered immoral or illegal in countries such as Thailand, Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam. Women who worked in such places did so to earn a living for themselves and their dependents.

Just before we left the parlour, he showed me the rooms and facilities he had offered his clients. There were eight rooms, each with a bed and a small shower stall. The rooms were clean. Then he took me to a heap of boxes covered with a bedsheet. He took off the bedsheet, and there were many condom boxes neatly arranged on a table. He said that he had bought 2,000 condoms from a businessman just before the town office closed his parlour. It had cost him a lot, and now he did not know what to do with them.

In my ‘back-to-office report’ (BTOR) to the ADB, I discussed the predicament of vegetable and fruit sellers and the parlour owner and his workers. I highlighted that the project had not yet paid them reasonable compensation or provided income rehabilitation assistance. I pointed out that compensation should not be limited to the land acquired. Those who lost their livelihoods and sources of income should also receive compensation and project assistance.

The Division Director at the ADB encouraged me to revise the BTOR and focus only on land acquisition and compensation. I hesitated to change the report. Two days later, the Chief Compliance Officer came to my room smiling and wanted to know more about my encounter with the parlour owner. He agreed with my analysis of the problems of project-affected persons. Still, he asked me to remove the details about the parlour from the report.

Features

Ditwah: A Country Tested, A People United

When Cyclone Ditwah roared across the island on November 27 and 28, 2025, it left behind a landscape scarcely recognisable to its own inhabitants—homes reduced to rubbles, vital infrastructure torn apart and entire communities engulfed by floodwaters that surged with terrifying speed. The storm’s ferocity carved deep scars into the island’s social and economic fabric, displacing thousands and severing lifelines that families had relied upon for generations. In its aftermath, the air hung heavy not only with the scent of mud and debris, but also with a palpable collective grief—a profound sense of loss etched on every face. As of December 9, the day of writing, the death toll had reached 635, with an additional 192 individuals reported missing. In Kandy alone, one of the most severely affected districts, 234 lives were lost. Island-wide, 12,123 families—amounting to 1,776,103 people—were displaced.

As a small island situated in the monsoon-fed waters of the Indian Ocean, Sri Lanka has long lived in intimate coexistence with hydro-meteorological hazards. For centuries, the monsoon winds that swept across the island brought not only life-giving rains to nourish paddy fields, forests, and communities, but also shaped the rhythms of daily life, agriculture, culture and even the island’s civilisation itself. Yet this same monsoon—when delayed, intensified, or disrupted—has had the power to unsettle entire ways of life and inflict widespread human suffering. Over generations, communities learned to read the sky and the sea, developing localised knowledge systems and adaptive skills to cope with the uncertainties of winds and waves. This reservoir of traditional wisdom fostered a form of social resilience deeply embedded in the island’s cultural fabric. At present, however, this traditional resilience is increasingly tested by the new realities of climate change and the growing frequency of severe cyclones.

When Cyclone Ditwah struck on November 27, 2025, it unleashed a force so violent that it reshaped many districts within hours, leaving behind a trail of destruction that stretched as far as the eye could see. Whole neighborhoods were crushed under winds that tore roofs from their foundations, while surging floodwaters swept through villages, carrying away homes, livelihoods, and the fragile sense of security people had built over generations. Roads lay fractured, communication lines collapsed, and families found themselves cut off in pockets of isolation marked by debris and despair. In the storm’s wake, the silence was haunting—broken only by the cries of survivors searching for loved ones and the distant hum of rescue teams navigating the ruins. The scale of the devastation was overwhelming, a human and infrastructural tragedy so profound that it demanded not just an emergency response, but a coordinated, compassionate, and deeply human-centered approach to crisis management.

The most devastating natural disaster Sri Lanka has experienced in recent history remains the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, which claimed over 35,000 lives and displaced nearly a million people. Sweeping across two-thirds of the nation’s coastline—more than 1,000 kilometers—it affected approximately 234,000 families and destroyed over a million houses. More than two-thirds of the country’s fishing fleet was obliterated. Beyond the immense human suffering, the tsunami exposed profound gaps in preparedness and underscored the urgent need for a systematic, coordinated approach to disaster risk management.

Over the last decade, Sri Lanka has increasingly confronted hydro-meteorological hazards driven by the accelerating impacts of climate change. Cyclones such as Roanu (2016), Mora (2017), Burevi and Amphan (2020), and Yaas (2021) highlight the growing frequency and severity of extreme weather events. According to the Sri Lanka – Disaster Management Reference Handbook, Cyclone Roanu brought the highest recorded rainfall in more than 18 years, triggering floods in 24 of the country’s 25 districts. Covering 1,400 square kilometers, the flooding affected nearly half a million people and inflicted damages estimated at US$600 million. Just a year later, Cyclone Mora caused severe flooding across 15 southern districts and unleashed landslides that further compounded human and infrastructural losses.

These climate-induced pressures have been accompanied by increasingly destructive monsoon-related disasters. In May 2016, the Aranayake landslide wiped an entire village off the map, killing 144 people, leaving 96 missing, and rendering hundreds homeless as their dwellings were buried under rubble. The following year, unprecedented monsoon rains caused flash floods and landslides that killed more than 210 people and displaced 630,000 across 15 districts. Subsequent monsoon seasons delivered similar devastation: in 2018, floods and landslides resulted in 24 deaths and affected 170,000 people; in 2019, heavy rains left 16 dead and displaced more than 7,000. Even in 2020, despite the successful evacuation of more than 75,000 residents ahead of Cyclone Burevi—an example of improved preparedness—post-cyclone flooding still affected over 100,000 people and destroyed or damaged nearly 4,000 homes.

Compounding this pattern of extreme rainfall and flooding is the paradoxical increase in drought conditions, another manifestation of climate variability. The worst drought in four decades struck between October 2016 and October 2017, affecting 2.2 million people across the North Western, North Central, Northern, and Eastern Provinces. From March to May 2020, another severe drought impacted more than 500,000 individuals in 14 districts, forcing the government to implement emergency drinking water distribution across six provinces. These cycles of excess and scarcity are further aggravated by the seasonal rise in vector and rodent-borne diseases—most notably dengue fever and leptospirosis—adding another layer of complexity to Sri Lanka’s disaster management landscape.

Societal Resilience in Disaster Management

As these converging crises demonstrate, Sri Lanka’s vulnerability to climate-driven disasters is no longer episodic but structural—woven into the lived reality of communities across the island. Yet amid repeated cycles of loss and recovery, what stands out most is not only the scale of devastation but the remarkable capacity of ordinary people to adapt, support one another, and rebuild their lives. This enduring strength points to a deeper truth: effective disaster management cannot rely solely on institutions or technologies; it must draw upon—and reinforce—the social resilience embedded within communities themselves.

Having lived under the influence of monsoons for generations, traditional communities developed sophisticated knowledge and skills to cope with nature’s unpredictability. Long before formal disaster management systems existed, villagers relied on environmental cues and collective action to prepare for seasonal threats. In the upstream and valley areas of the Kalu Ganga, for example, older generations still recall how communities repaired boats and rafts through shramadana well before the rainy season began. They observed the behavior of birds, animals, and changes in wind patterns to decode early warning signs that modern meteorology would later confirm.

Such practices demonstrate that traditional communities were not merely passive recipients of natural hazards; they were active interpreters of their environment. Their resilience stemmed from a deep ecological intimacy, a lived knowledge system refined through experience. Today, there is immense value in unpacking this traditional knowledge and synergising it with modern technology—not to romanticise the past, but to strengthen contemporary preparedness.

The Role of Community and the Political Domain

Building societal resilience requires more than cultural memory; it demands structured collaboration between communities and the political system. While communities are often the first responders in any disaster, the political domain plays a crucial role in mobilising, legitimising, and coordinating their efforts. Transforming political will into national will requires an organic articulation between civil society and political leadership—a partnership where both domains reinforce one another rather than operate in isolation. Within this broader framework, disaster management encompasses three equally critical components:

Disaster Risk Management

In each of these, the state has a vital role—from policy formulation to resource allocation, coordination, and accountability. Yet, the effectiveness of state-led initiatives ultimately hinges on the strength of the relationship between institutions and the communities they serve.

Beyond Culture: Technology and Institutions as Pillars of Resilience

While socio-cultural resilience forms an indispensable foundation, it is no longer sufficient on its own, given the scale and complexity of contemporary climate-induced hazards.

Modern disaster risk management relies on a robust interface between technology, institutional networks, and community participation. Advanced and accessible communication technologies—early-warning systems, mobile alerts, satellite data, and community-level dissemination platforms—play a crucial role in transforming timely information into effective action.

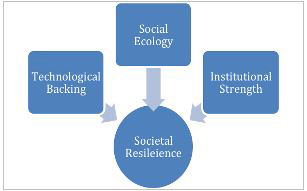

But technological tools reach their full potential only when supported by strong institutional structures, in both formal and informal, capable of mobilising people and resources rapidly and equitably. Thus, societal resilience can be understood as a system supported by three interdependent pillars.

Societal Resilience

When these elements function in harmony, the collective capacity to withstand and recover from disasters is significantly enhanced. Ultimately, social resilience is not merely the ability to endure shocks—it is the ability to recover with dignity. A humane disaster management system recognizes the agency, knowledge, and lived experiences of affected communities. It integrates cultural wisdom with modern capabilities, fosters trust between citizens and institutions, and ensures that every step of the disaster cycle reflects empathy, inclusion, and respect.

Immediate Community and Government Responses to the Crisis

Within ten days of the Ditwah disaster, the Sri Lankan government succeeded in rapidly mobilizing the security forces, key institutional structures, political leadership, and community organisations to confront the crisis. Given the scale and depth of the devastation, meeting the challenge and mitigating its effects seem to be a formidable task. The armed forces and government departments, supported by unaffected communities, provided exceptional assistance to meet the initial challenge. People in the South—often guided directly or indirectly by local political/community leadership—volunteered in large numbers, travelling to the hills to support recovery efforts. Much of the initial work of clearing debris and cleaning homes was carried out through community participation. Infrastructure repairs, particularly the restoration of roads, water supply, and electricity, were undertaken through coordinated action by relevant government agencies who worked tirelessly day and night. As a result, nearly 80 per cent of essential infrastructure was restored within ten days, with the exception of the severely damaged railway network, which requires longer-term reconstruction.

In the immediate aftermath, the government declared a nationwide state of emergency under the Public Security Ordinance, enabling the rapid deployment of resources across sectors. Through the Disaster Management Centre (DMC) and relevant ministries, authorities activated emergency operations: evacuation orders were issued in high-risk flood and landslide zones, shelters were established across the country, and search-and-rescue missions commenced immediately after landfall.

Concurrently, the government announced a comprehensive relief and recovery package. Affected households received allowances for cleaning and resettlement, support for temporary accommodation, and financial assistance for the repair or reconstruction of damaged homes. Immediate access to financial resources—including a Rs. 30 billion contingency allocation that did not require prior parliamentary approval—enabled swift implementation. The declaration of this extensive and unprecedented relief package played a key role in restoring hope and strengthening the self-confidence of affected communities.

Recognizing the magnitude of the crisis, the government established a special recovery fund that brings together public and private sector contributions to support long-term reconstruction, infrastructure repair, and livelihood restoration. Involving prominent private sector leaders—including those who are not aligned with the ruling administration—alongside government officials and key ministers is intended to build trust within the business community and reinforce transparency in the fund’s management. The substantial international assistance received and pledged reflects a renewed confidence among external partners in the government’s ability to manage funds transparently and ensure that aid reaches intended beneficiaries. Sri Lanka further collaborated closely with international and humanitarian agencies to scale up multi-sector support. Organizations such as the World Food Programme (WFP), International Organization for Migration (IOM), and World Health Organization (WHO) mobilized food, water, medical supplies, shelter materials, and rapid-response teams—often in coordination with government efforts—to reach displaced persons and vulnerable populations, particularly in remote and landslide-prone areas.

During this ten-day period, the President personally attended the district coordinating committee meetings in all cyclone- and flood-affected areas. These meetings brought together political leaders—both from the ruling party and the opposition—along with key administrative officers and representatives from the relevant line ministries to review disaster response, mitigation measures, and recovery needs. The manner in which the President raised issues, sought clarification, and directed action demonstrated a high level of preparation and a clear understanding of the scope and complexity of the damage. His engagement signaled a proactive and informed approach to crisis governance, contributing to more coordinated and timely interventions across affected districts.

Thus far, these measures largely pertain to confronting the immediate challenge and mitigating its impacts. Yet effective mitigation must ultimately lead into long-term recovery planning and strengthened preparedness for future climate-induced crises. Ditwah is not the first or the last. Climate change has altered the frequency, scale, and unpredictability of extreme weather events, making it clear that Sri Lanka must now learn to live with recurring climate hazards as a structural condition rather than an episodic disruption. This requires a sustained investment in resilient infrastructure, risk-sensitive development planning, and community-level adaptive capacity. In this sense, the response to Cyclone Ditwah should not only be understood as an emergency undertaking, but also as a critical moment to embed long-term climate resilience into national policy and institutional practice.

Lessons learned

The devastation wrought by Cyclone Ditwah has once again tested Sri Lanka’s institutional capacity, the NPP political leadership and peoples’ resilience. Since the 2004 Tsunami, the country has made significant progress in establishing organisational structures and policy frameworks for disaster management, making it a central domain of contemporary statecraft. Yet, the experience of Ditwah underscores the need for further strengthening in four key areas. First, given the multiplicity of ministries and agencies involved—from the Ministry of Disaster Management and the National Council for Disaster Management to the Disasters Management Center, the Meteorological Department and the National Disaster Relief Services Centre—clear mechanisms are essential to avoid overlap and ensure coherent, efficient action.

Second, disaster preparedness and response must harness the collective capacities of state institutions, NGOs, and community-based organisations, whose collaboration is indispensable for effective disaster risk governance. Third, the integration of traditional knowledge systems—rooted in long-standing practices of environmental stewardship and community resilience—should inform planning and implementation, complementing modern technology and institutional expertise. Finally, in a multi-ethnic, post-conflict society, sensitivity to ethno-political dynamics is imperative across all three phases of disaster management: preparedness, emergency response, and post-disaster recovery.

Ultimately, Cyclone Ditwah revealed both the vulnerabilities and strengths of the nation—demonstrating that while Sri Lanka’s systems were tested, its people were united in response, reaffirming the country’s capacity to confront adversity through collective resolve. The spontaneous networks of support that emerged in the cyclone’s aftermath demonstrated that unity is not merely an aspiration but an operational force in moments of crisis. In reaffirming the country’s capacity to confront adversity through collective resolve, the response to Ditwah offers a powerful reminder that the resilience of the people remains Sri Lanka’s most reliable foundation for future challenges.

by Prof. Gamini Keerawella ✍️

Features

Rare Seahorse discovered in Sri Lankan waters sparks urgent conservation debate

Sri Lankan marine researchers have formally documented the presence of the rare and Vulnerable Three-Spot Seahorse (Hippocampus trimaculatus) in Sri Lankan waters for the first time, an important milestone in the country’s marine biodiversity records.

The discovery was made through the examination of four dried specimens collected from fishermen operating off the southern coast near Madiha, nearly 150–200 km offshore. The evidence confirms that the island’s marine ecosystem hosts a greater diversity of seahorses than previously recognized.

Until now, only two species—Hippocampus kuda and Hippocampus spinosissimus—were scientifically confirmed in Sri Lanka, both largely linked to the northwestern lagoon systems. This discovery shifts that narrative southward.

Lead scientist Janamina Bandara emphasised the importance of the breakthrough, saying the identification not only verifies the species’ presence but also extends its known distribution range in the Indian Ocean.

He told The Island:”This is the first authentic record of Hippocampus trimaculatus from Sri Lankan waters. This species was assumed to occur here based on regional presence, but until now, we lacked verified scientific proof.”

Found in an Unexpected Habitat

While seahorses are typically associated with seagrass beds, shallow estuaries, or mangroves, the discovery revealed a surprising observation—these specimens were found attached to floating masses of marine debris.

Bandara described it as one of the most unusual natural behaviours documented in local marine fauna.

“The specimens appear to have utilised drifting debris as habitat, which has not been explicitly recorded before,” he explained.

Photographs obtained from young field biologists show pieces of plastic waste, frayed fishing nets, fabric residues, and other floating refuse entangled into large drifting clusters.

Marine scientists say this phenomenon—informally referred to as “floating artificial reefs”—has been increasingly documented elsewhere in Asia and the Pacific. However, Sri Lanka has lacked records until now.

Bandara added that the drivers behind such habitat use remain unclear, raising questions about whether this behaviour reflects adaptation or desperation.

Specimens Documented, Sexed and Archived

The research team collected four specimens—one male and three females—over two separate encounters, in March 2024 and June 2025. Measurements included head-to-snout ratios, ring counts, and coronet shape, all critical criteria in identifying seahorses.

“All diagnostic features matched published descriptions, including distinct hook-shaped cheek and eye spines,” Bandara confirmed.

The specimens have since been deposited at the University of Ruhuna for long-term academic reference.

Illegal Trade Still Active

The finding has also shed light on the continuing illegal trade of dried seahorses in Sri Lanka—an industry long suspected, but seldom traced with scientific evidence.

The specimens originated from fishermen who admitted they sell dried seahorses to intermediaries and tourists. The team found that prices vary by size and buyer type.

“Smaller specimens sell for roughly Rs. 1,000 locally, while foreign buyers pay up to Rs. 5,000. Larger specimens fetch significantly more,” Bandara said.

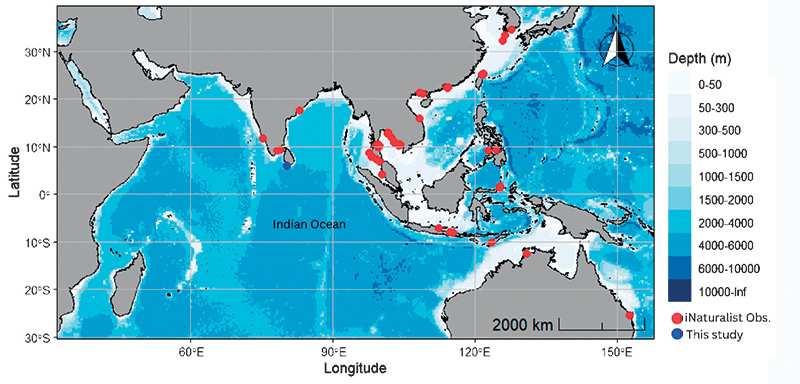

Map. Known distribution of Hippocampus trimaculatus with the current study site indicated. Red dots: confirmed research-grade observations (n = 76) of the species from iNaturalist. Blue dot: study site location (Madiha coast, Southern Sri Lanka).

Many dried specimens are reportedly converted into gold-plated pendants, marketed under the claim of bringing luck and prosperity. In some tourist markets, dried seahorses are sold discreetly alongside shells and corals.

While enforcement exists, Bandara says it remains largely symbolic.

“Raids happen, but are limited. Without awareness among fishermen and tour operators, the trade will continue,” she said.

Global Conservation Context

The Three-Spot Seahorse is listed as Vulnerable by the IUCN Red List and is protected under Appendix II of CITES, meaning its international trade requires permits. The species faces high risk from:

Bycatch in trawl fisheries

Rising demand from Asian traditional medicine markets

Rapid habitat decline due to marine pollution

Slow reproductive turnover

Seahorses exhibit monogamous pair bonding and unique male pregnancy, making their populations extremely fragile when harvested.

Sri Lanka, positioned at a central point in the Indian Ocean trade network, remains vulnerable to illegal wildlife trafficking routes.

Bandara emphasised that biodiversity verification has regulatory relevance.

“Scientific records strengthen diplomatic and policy decisions. Without confirmed presence, enforcement remains weaker,” she explained.

Calls for Greater Action

Following the discovery, the research team is urging local authorities and NGOs to prioritise:

Awareness programmes for coastal communities

Monitoring of multi-day fishing vessels

Inclusion of seahorses in biodiversity assessments

Tourism-season enforcement in southern coastal markets

Bandara believes this new evidence allows Sri Lanka to become an active contributor to global seahorse conservation efforts.

A Turning Point for Marine Biodiversity Research

Beyond the immediate conservation implications, this finding marks one of the most scientifically significant marine records of recent years.

It suggests that Sri Lanka’s offshore ecosystems are both understudied and vulnerable to emerging human-driven pressures. Researchers now believe more undocumented marine species may inhabit local waters, awaiting formal identification.

“This discovery is not only a scientific milestone but also a reminder that our oceans hold species that are disappearing faster than we are documenting them,” Bandara said.

As marine debris continues to accumulate and demand for illegal ornamental wildlife persists, researchers warn that scientific discovery alone will not ensure the species’ survival.

Bandara says what happens next will determine the fate of this newly confirmed marine icon.

“If we act now—educate, regulate and monitor—we stand a chance to protect these animals before they vanish unnoticed.”

By Ifham Nizam ✍️

Features

Human-elephant conflict and housing needs of villagers

During the recent Ditwah cyclone, elephants were seen floating in treeless floodplains that were once their forest habitats. On a good-weather day in 2017, near Kokilai, the Navy found a pair of elephants riding waves after a beach outing two kilometers offshore in the high seas. Divers guided them ashore after a 12-hour struggle. Trains barrel through elephant herds regularly, decapitating half a dozen in one tank. A herd of elephants over 100 parades across a highway serenading motorists stuck in a kilometer-long traffic jam. Recently, adding insult to injury, a lone elephant was sitting deep inside a latrine pit behind a small house, and was dug out by a caterpillar tractor. A speeding bus ran over and killed a baby elephant, and police shot dead the mother who stood crying over her baby’s body. The tusker named Sinharaja was still a baby when the Army pulled it out from an agri-well some years ago in Nuwarakalaviya. He is now royalty tasked with carrying the sacred tooth relic at the Dalada Maligawa. These extraordinary events, rubrics of a national drama, show that fates, ours and elephants, are inexorably linked.

Over 7,000 elephants and countless villagers in Sri Lanka are torn apart daily by myriads of unpleasant encounters. Our elephant population is multiplying alongside us, making these encounters even more remarkable. As the government owns all elephants and writes laws for them, it also owns the product of these encounters. Since it has law books for the villagers, too, it cannot disregard the mess its protégé, this patrician in the wild, leaves on the villagers’ doorstep. Only the government can find a lasting solution to blunt the prickly edges of this national emergency, but not without contributions from the villagers.

George Orwell wrote in Animal Farm, “Some animals are more equal than others.” But the sentimentally charged public opinion about our cultural icon cannot outweigh the burden it placed on villagers living on the edges of elephant habitats.

As will be explained later, I propose a Gam Udawa-type house for each newly married couple who choose to remain within their village’s boundaries. If anyone edits this out as impractical, please come down from the ivory towers and visit a village bordering an elephant corridor to see for yourself the internecine damage elephants and villagers cause to each other.

There is no rich body of literature on the kinetics of village housing. But the volume of villagers’ experience is a safe guide to navigate it. I saw, over the span of three decades, how a major elephant corridor, one or two kilometers wide, adjoining my village above Mahakanadarawa reservoir, got swallowed up as villagers built (and still do) homes there. Thus, one way to stop this is to contain the village where it is now. Halting home-building activities in elephants’ homes is a futuristic idea that the government has not tried. This experience also suggests that a study of the environmental impact of new village housing is in order.

Little parts that drive conflict

The government does not hear or see the little parts that drive the human-elephant conflict in the village. The only elephant problem it has is an 8 am to 5 pm thing, caged and tied to concrete stumps with steel chains at a compound in Dehiwala, minutes from Colombo’s urban universe. Together with Dehiwala, provincial compounds like Pinnawala, and a few national parks hold less than 1% of the Sri Lankan elephants, leaving the rest to roam around and harass villagers. Officials who have the power and know-how to resolve this tragedy do not feel it in real time. They do not live anywhere near where elephants live.

Indeed, it is a stretch one may suggest the government can find new space for the elephants like grandiose, unwieldy ideas like port-city-style landfills along the coast. However, we can work with existing landmasses more studiously using other methods. Driving elephants to the current Managed Elephant Ranges (MER) is not one of them. MER seems to lack sufficient food, as evidenced by the emaciated elephants we see in these ranges. An elephant is a big animal and needs a bigger lunch setup.

HOW WE GOT HERE

Until the mid-20th century, abundance of forest accommodated all villages and some more elephants; there was no reason to think villagers were taking elephants’ feeding ground any more than governments had any plans to reduce friction before it reached an unmanageable level. Elephants’ feeding grounds occupied forest area about two kilometers wide in higher ground between two tank cascade systems, each independently sharing water from parallel watersheds.

Islands in the sea of forest

Villages in the North Central, Northwestern, Eastern, and eastern half of the Southern Province remained as islands in this sea of forest. Collective personality embedded in the village was that residents could hunt, harvest timber, and make small chena plots in these forests. The concatenation of many such forest buffers formed elephant highways that were major feeding grounds. Everyone lived happily until the government’s neglect in addressing the population explosion of elephants and our own created the present predicament like a Class 4 wound.

A village community is a swarm, usually numbering around 100 individuals. Increasing membership in a swarm trigger some to move out to new locations. In a colony of bees, for example, an alternate queen bee will lead a part of the overpopulated colony out to set up a new community. Similarly, in the village, where two or three couples marry each year, and if the space for housing sites is limited, as is the case in old villages, a couple might emigrate to another village or town. The one or two with what biologists call the ‘group mind’ stay in the village, becoming the seeds that begin to spawn more warms, amplifying the elephant-human problem.

The new couple is looking to build a house closer to their larger family. But as space for potential housing is gone, the next option is to move beyond the traditional village boundary, where the one- to two-kilometer elephant feeding grounds begin. On these grounds, this family finds not only a spot for a house but also timber that had been the property of elephants and other wildlife since before the village’s genesis. In a nutshell, this is how elephants began to lose their land.

Land grab

With this land grab, though isolated, friction over space ensued, leading to physical confrontation with elephants. The government’s inaction in mediating this problem is telling.

As years go by, this progression has led to the appearance of dozens of new home gardens, each slowly taking up at least a hectare of virgin forest. In a few decades, hundreds of such hectares will have been devoured by these progenitors entering the village marriage fraternity.

Meanwhile, the explosion of the rural population seems to influence the mechanics of elephants’ behavioral evolution. Back then, elephants were shy. I remember a herd disappearing into the woods in seconds after seeing a moving firebrand tipped with glowing embers. Aiming a flashlight made the herd disappear into the woods like blowing smoke into a beehive. In contrast, now a wild elephant caparisoned with a dry crust of mud bath walks casually on a road, duly giving right of way to motorists, and stops by a lonely roadside tea kiosk. He waits patiently, not for tea, but until the kiosk owner offers him a bunch of ripe bananas!

Today, elephants are so common and share our space more often, villagers assign lovely names to identify tuskers. In our childhood, we rarely saw a tusker because he owned a large swath forest, so his contact with us was minimal. Hence, the name tag was the least he needed.

HOUSING IN CITY AND VILLAGE

Whether people live in a crowded city with sprawling multistory housing compounds or in a village with two dozen homes under an irrigation tank, their universal human need is housing. In the city, with limited horizontal expansion, the housing idea must become improvisational. Thus, it grows vertically because it’s the only direction the cramped city can build. Having no such problem, after the old gammedda ran out of space, villagers moved horizontally to new tracts of forest beyond the village borders. Missing in the discussions on the loaded thesis of elephant-human conflict is this premise – the housing need of newly married villagers, the overarching subtext of this problem, not seen by anyone outside of the village. This married couple clear a track of forest, marking the beginning of the gradual encroachment of the village into an existing elephant range.

When it comes to housing, villagers in elephant-roaming areas are left to fend for themselves. Overcrowding in villages had not received the government’s attention because it never put a premium on housing in a village.

Both parties are victims here. Any steps to help them have become untenable due to poor management (of the problem) and the uncontrolled population upsurge of the parties. This drama is what the successive governments have missed seeing. Although the government and private sector have been generous with housing issues in the city, not extending the same kindness to villagers is why they are in this loveless embrace with elephants.

Meanwhile, beginning in the mid-20th century, the city has adapted to meet its residents’ housing needs. The scale ranged from clusters of one-room homes like UC Quarters in Urban Council jurisdictions, to modest multi-unit housing compounds, ‘flats,’ like the eponymous ones at Narahenpita, Maligawatta in Colombo. Over the past couple of decades, towering megastructures catering to the new affluent residents have further diversified the city’s housing options.

The elephants are wanderers and have all the land to move around. But villagers are no longer the itinerant bands they once were in their distant past. Due to their proclivity to acquire acreage from freely growing forests, they become fixed targets for elephants. But don’t accuse the villagers of being xenophobic towards elephants. We see they never show schadenfreude – enjoying an elephant’s misfortune, while it struggles to climb out from an agri-well or a canal. Instead, standing on the edge, they speak kind, encouraging words to the traumatized animal. Some even throw banana stumps at him to eat.

FAILED HOUSING PROJECTS (WIYAPARA) IN THE 1980S

Often, the government itself is the culprit of expanding the village into elephant corridors by introducing new housing projects. Such housing schemes were called wiyapara gewal (project homes). It turned out to be a failed government idea.

Near my village, in the 1980s, the government marked off housing plots along a cart road that ran through a 2-kilometer elephant corridor which began from the end of our tank bund. This stretch separated us from a series of neighbouring villages in the upper reaches of the Mahakanadarawa reservoir, built in 1959. Until then, elephants freely moved between Padaviya, Nachchaduwa, and Kalawewa tanks, using forest corridors between tank cascade systems, including the above, rarely entering villages.

After Mahakanadarawa gobbled up an extensive virgin forest area, elephants circumventing it on the way to Kalawewa stumbled upon a surprise: a society of homes was sitting on the above forest corridor that had always belonged to them. Villagers cut down the verdant forest and started home gardens in their place under the aegis of the aforesaid wiyapara project. It bridged the neighboring village into one extended community. One family even fenced off the kamatha-sised water hole that elephants enjoyed on the rocky outcrop called Wannamgala and enclosed it in the new garden lot with the sign “balla hapai” (dog will bite)!

The Member of Parliament for the area was behind this project, with a piecemeal aid package worth about Rs. 25000 to each land recipient. With that kind of economic magic wand, a half dozen villagers yielded, and now this row of houses bisects what was an elephant highway, sending elephants’ equanimity to coexist with human settlers downhill. Historical blunders like this tell us to reconstruct untested housing concepts to fit the present.

FEW PROPOSALS

Discouraging villagers from spilling beyond village boundaries to build new homes must be a priority in any plan designed to address elephant management issues. It is a way to stop the slow oxidation of elephant corridors where newlyweds continue to stake out claims for home sites.

It is unfair to deny villagers the opportunity to own a piece of their own home garden. On its part, the government can help by creating employment or home-garden opportunities by introducing them to garden crop methods and small-scale industries, which will provide them with a meaningful livelihood and a reason to stay within the village’s borders.

The government must also devise the same plan it uses to address overcrowding in city swarms, by building small irrigation colony-type houses within the village situated for newlyweds in villages on the borders of elephant habitats. New families will appreciate this idea that their government is giving them a hand with a small house within the village limits.

My proposal may sound like a fictive reverie. But math speaks for itself. Consider this: conceivably, if we can prevent that one newlywed couple from carving out its space in a forest tract used by elephants, after a few decades, we would have saved dozens of hectares for elephants by preventing couples from moving there to build new dwellings.

I ask the government not to think of the pink elephant – the cost – in considering this project. If it cannot build the house for free, recover a partial cost from new owners in easy installments based on their verified income.

There are many private and public tracts within a village that remain fallow or undeveloped. The government can offer to purchase these to build new homes. What happened to Alfred House Gardens in Colombo – 3 over a century ago gives us ideas on how to apply the summary of that history to a village where, generally, real estate behaves similarly.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the owners of Alfred House Gardens partitioned the opulent estate, endowing it to the city for a greater purpose. My premise here is that a villager with his own Alfred House estate in the village, parts of which remain fallow, may wish to place a corner of it on the market for ready cash. Suppose the government offers an enticing price. In that case, I have no doubt the owner might consider it. Haven’t we seen this in newly partitioned large coconut plantations elsewhere?

The government will then build a small house here and bestow it on the newly married couple. This is one couple that will not pose a threat to elephants’ right of way. If we can push this simple idea to fruition, in a decade or two, encroachment into elephants’ roaming lanes can be reduced considerably around this village. A fitting paradoxical allegory for this is an African proverb that says: “The way to eat an elephant is to take one bite at a time.”

Furthermore, the government may amend the President’s Fund or create an Elephant Fund to provide small housing loans specifically to newlywed couples in such villages. It must suspend the irrational, sneaky and flagrant absurdity of tax-exempted vehicle imports, now allowed to certain privileged government officials. Tax this exclusive club and use the money for this program. Each new car landing on Sri Lankan soil will pollute the environment and be one more headache for elephants feeding at Minneriya tank.

To identify which villages are likely to encroach on elephant corridors, the wildlife department must survey and designate their boundaries. This step is every bit as essential as declaring stretches of forest as elephant corridors. Also, an accelerated tree-planting program to rehabilitate deforested areas on the edges of elephant corridors must be a government priority.

The government must not reward large farming interests and the solar power industries by allowing them to take up elephant habitats. A papaya plantation has alternatives that an elephant family does not.

Finally, failure to resolve this problem will itch our nation’s conscience and shame us deeper. The few patches of forest we can keep uncleared are the ones that tell us just how many more hectares of them refuse to be cleared.

Lokubanda Tillakaratne chronicled life in a village in Gammadde Ninnadaya, and a defunct traditional judicial system practiced in Nuwarakalaviya villages in Rata Sabhawa (Sarasavi Books).

By Lokubanda Tillakaratne ✍️

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoThe Catastrophic Impact of Tropical Cyclone Ditwah on Sri Lanka:

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoHandunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoSri Lanka betting its tourism future on cold, hard numbers