Features

Childhood memories of Batticaloa and working there in the fifties

(Excerpted from Fallen Leave, an athology of autobiographical memoirs by LC Arulpragasam)

I have happy memories of Batticaloa as a boy. My father was posted there as Medical Officer of Health for a period of five years in the late 1930s, when I was between eight-12 years of age. Since I was attending school in Colombo, my days in Batticaloa were confined to the school holidays. But these were days which made a great impression on me, drawing me to my love of water and to the jungles and the great outdoors. In 1955, I was posted as Assistant Government Agent of the Batticaloa District, which gave me a wider view of the district’s problems and possibilities.

General Overview

The first thing that strikes an independent observer is the spatial distribution of population in relation to overall land availability in the district. Almost 80 per cent of the population is settled along the narrow (north-south) coastal littoral, sandwiched between the lagoon on the west, and the sea on the east. This is somewhat strange for two reasons: first, because this coastal land is relatively poor and sandy, except for places where a few rivers spread their fertile silt; but secondly, because this has resulted in some of the greatest population densities in the country, especially in the areas of Kattankudy and Kalmunai.

This settlement pattern may have been convenient because of the relative ease of communications along the coast, while also providing a stable livelihood from farming, fishing and trade. In the long run, however, it has had the negative consequence of not utilizing the most fertile lands of the district for cultivation. This in turn has enabled the subsequent appropriation of these lands by the Government for settlers from other parts of the country.

The second most striking feature is the abundant availability of land compared to the rest of Sri Lanka – especially compared to the miniscule holdings in Jaffna or to the very small holdings in the hill districts (except for the large tea estates). I was amazed and amused when a farmer asked me for more land, saying: ‘I am a poor man, your honour sir, I have only six acres and need more land to feed my family.’ It is true that the land is relatively sandy and receives rain in only one season; but it is also true that the Batticaloa district does have a more favorable land-man ratio than most other districts in the country.

This relative abundance of land has served, in my opinion, to inhibit, first, any great desire to intensify agricultural production. If one wanted more income, one merely had to acquire more land. Second, it inhibited enterprise, including a search for higher education or for higher jobs outside the district.

This is in sharp contrast to the situation in the Jaffna district, where the shortage of land forced the Jaffna Tamils to actively seek education and government jobs in other districts – or even other countries. The same applied to business or commercial ventures. There was no major industry in the district in 1956. Even the two top general stores in Batticaloa town were owned by Sinhalese merchants from Galle and Matara. More remarkable was the relative lack of higher education among the Tamils and Muslims of the district at that time.

A real anomaly and grievance during the 1950s was the near-monopoly of top government posts in the district by Jaffna Tamils. This was partly due to their higher education levels and seniority in the government service compared to the Battticaloa Tamils and Muslims at that time, while their Tamil-speaking skills gave them an advantage over eligible Sinhalese officers.

For instance in 1956, whereas there was one senior Sinhalese staff officer (the DLO) in the district, there was not a single staff officer who hailed from the Batticaloa district. Few Batticaloa Tamils or Muslims bothered to seek higher education or higher government positions at that time; they seemed to prefer to look after their own lands rather than to work outside their district. This near monopoly of higher government posts by Jaffna Tamils was naturally resented by the rising intelligentsia in the district.

Fortunately the balance has been rectified by the increasing number of graduates from the Batticaloa district who have since assumed high staff positions. This was greatly helped by the establishment of a University in the Eastern Province. This was neither the case in my father’s time in the 1940s, nor in my time in the 1950s.

Exaggerated Respect for Government Officials

Another related trait was the over-dependence on the government bureaucracy in times of need. There were no NGOs to speak of. This dependence manifested itself especially in times of crisis, such as during the communal riots of 1956 and 1958, as well as during the devastating floods of 1957/58. Whenever there was a crisis, they always looked to the Government Agent for a solution. This also led to the overly high respect accorded to high government officials – which is not so common in other districts. I know that this sounds patronizing now, but this was the situation in 1955, around 65 years ago when this was written.

Even the form of address to these higher government servants was usually overdone. At inquiries, I was often addressed as ‘Your honour, Sir’, while even senior clerks would address me in the respectful third person. This exaggerated respect for government office was also reflected in the local population. The Batticaloa Kachcheri happens to be located in the old Dutch Fort. When I drove through its portals each day, all the people in the large courtyard would stand up, although I was only 26 years old at that time, and was only passing through to park my wheezing old Morris Minor! They would continue standing as a show of respect for my official position, causing me to cringe past them guiltily, to reach my own office!

This respect for government authority may be partly due to the quaint institution called dappu, which requires permission from the GA before any paddy land can be cultivated for any season. Can you imagine that everyone had to get permission to cultivate his or her own paddy land for each season? Not only did this cast a heavy burden on the GA’s office, but it greatly enhanced his authority. Especially in cases of cultivation disputes, lawyers would appear before me for each party, because the winning of cultivation rights was more than half the battle in later winning ownership rights in court. Given the frequency of these disputes, I just put my head down and worked, giving dappu decisions left and right. I must admit that in retrospect, I am now rather embarrassed that I did not question the rationale of this burdensome system – or try to abolish it altogether.

The colonial overhang of exaggerated respect for higher government officials was also reflected in the social scene. In British times, the latter was dominated by the Gymkhana Club, which was open only to higher level officials of the government service; this in practice ensured that it was open only to whites (the British). But in my father’s time in the district (1939-1944), the senior Ceylonese holding high-level government posts (of whom my father was one) were allowed to become members. Even then, as a boy, I wondered why the best tennis players in the district were not allowed into the Gymkhana Club.

When I assumed duties in the Batticaloa District in 1955, I was surprised to find that the Gymkhana Club still insisted on these same arcane and ancient rules. The Government Agent was still the ex-officio President of the Club, while I as Assistant Government Agent (at the age of 26 years) was automatically its ex-officio Vice President! I had no difficulty in persuading the GA at that time, Mr. A.B.S.N. Pullenayagum, an upright and unassuming gentleman, to jointly co-sponsor a motion to abolish the rules that made us automatically the President and Vice- President.

We also proposed another motion to open the Club to non-staff officers in the government service (such as police and excise inspectors), which would greatly increase the number of sportsmen in the Club. It did little, however, to bridge the gap between the higher social status of government servants and the public at large, who were still denied membership, which was reserved for government servants only. Fortunately, because of my work, I had professional and social dealings with lawyers and others in the district, among whom I had some friends.

Moreover, my work in agriculture and lands brought me into intimate contact with the farmers, who formed the backbone of the district: I cannot recount how much I learned from them. I was fortunately able to give something back in return. By working more hours per day, I was able to give out more land to the landless and land-poor than had been given out by any of my predecessors.

The natural beauty of the Batticaloa district

The last impression I would like to leave with you is the beauty and variety of this district: its people, its jungles, lagoons, and beaches, which were especially attractive to me, an outdoors man. To live in an old government bungalow immediately by the lagoon, as was my official residence in Batticaloa, was my idea of heaven. I used to get up to the calm of the lagoon in the mornings and sit up at night just to see the moonlight on the water and hear the lapping of its wavelets on the shore.

I happened to own a small skiff (made of aluminum) in which we used to row out from our house in the moonlight to hear the famous ‘singing fish’ of Battticaloa! I have swum and fished in its rivers and lagoons, and in the changing tides of its seas. I have ventured in my little boat to the farthest ends of lakes and reservoirs in the heart of the jungle, seeing tree upon tree of nesting birds. I have rowed within 30 feet of wild elephants, who although surprised, could not reach me – for I was in my little boat in deep water!.

The theory current in the 1950s was that the ‘singing fish’ could only be heard near the Kalladi Bridge, since the musical sounds were caused by the constriction of the tidal flow of water under the bridge on moonlight nights, and not by ‘singing fish’. But going in my little aluminum boat, whose metal conducted and magnified the sounds in the water, I have heard the notes (like a cacophony of instruments tuning up for a concert) in many other parts of the lagoon, far away from the bridge –and even opposite my own bungalow – but only on moonlight nights.

Although not a keen hunter, I have shot a leopard in the jungles off Arugam Bay. (It was ‘sportmanship’ in the1950s, although I regret it now). I have trekked through the jungles of Panama Pattu into the Yala Game Sanctuary in the Southern Province. I have seen the wild peacocks dance: I have walked to the jungle habitat of the Veddas in Bintenne – and more.

The Batticaloa District thus offered me not only opportunities for useful work, but also opportunities to enjoy life to the full. Both the happiest years of my childhood and the most rewarding years of my professional life were spent in that district – for which I am truly grateful. I find that the gratitude is mutual: I have just learned, after 65 years, (when this was written) that an entire tract of paddy land has been named after me, with the name: “Arulpragasamkandam”.

Features

US Election Down to the Wire, Sri Lanka has Turned the Page

by Rajan Philips

In about ten days, on November 5, the US will have its quadrennial presidential election along with its biennial House and Senate elections. The presidential election is literally down to the wire, and the two candidates, Kamala Harris and Donald Trump, are fighting it out at the margins in the so called seven swing states. At the time of writing, it is a total toss up and there is no certainty about the outcome.

In a presidential election year, the American voters mark their ballots to elect their president for four years, a third of their 100 senators for six years, and all 435 members of the House of Representatives for two years. The elections to the Senate and the House are called the ‘down ballot races’, below the main presidential runoff.

Traditionally, voters used to vote the same way (either Democrat or Republican) up and down the ballot. Not anymore. And the candidates up and down the ballot are also vigorously minding their own races without too much of a co-ordinated effort to sustain a unified campaign.

Trump doesn’t care if the Republican Senate and House candidates are winning or losing. He only cares about his result for he needs to win the election to make sure that he puts an end to all the court cases against him. If he were to lose, he is more than likely to be convicted and jailed over one or more of the many charges against him.

Kamala Harris would normally be concerned with down ballot races to make sure that her party does well enough to gain control of both the Senate and the House for her to be effective and consequential as president. But with all the races being so tight, it has become a case of each one for oneself and money for all.

One ray of optimism is that if Vice President Harris were to win the election and see off Trump, it will also free the Republican legislators from Trump’s stranglehold and make a good number of them amenable to co-operate with their Democrat counterparts for passing critical legislation and authorizing funding for executive initiatives. That is the way, bi-partisan consensus in the middle, the American system has been working for nearly two centuries.

The scary and not at all unlikely scenario is the Republican jackpot – Trump winning the presidency and the Republicans taking control of both the House and the Senate. Trump will get rid of all the cases against him, and he will slash corporate taxes and create a deregulated environment for billionaire businessmen. Many of them led by Elan Musk are openly bankrolling Trump’s election campaign.

With a jackpot victory, the Administration will force Republican legislators to pass enabling laws to implement the loony agenda of ‘Project 2025’, the handbook of action items for Trump’s second term prepared by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank group. The Supreme Court with its super majority of conservative judges is well set up to give judicial cover to whatever the second Trump Administration may want to do.

Turn the Page

In another ten days after the US election, on November 14, Sri Lankans will be voting to elect a new parliament that will have to cohabit the island’s state with its new President – AKD. Cohabitation in presidential parlance refers to the situation in which the executive president and the prime minister in parliament belong to two different political parties. The implication is that a presidential-parliamentary system works best when the president and the prime minister are from the same party. When they are not, cohabitation will ensue with all the risks that it entails. That is the system that is in France that Sri Lanka has copied with expedient changes. The US system is different.

The late JR Jayewardene, the father and the mother of Sri Lanka’s presidential system, had a fondness for envisaging Sri Lanka’s new presidential system and the old parliamentary system evolving into being in a marital relationship. That presupposes the president and the prime minister belonging to same party. But JRJ did not quite pay much attention to the possibility and attendant risks of the two belonging to different parties. He may have tried to forestall this possibility by contriving to keep the UNP permanently in power, but his schemes ran out of steam after 17 years in 1994. And it has been a slow death for the UNP ever since.

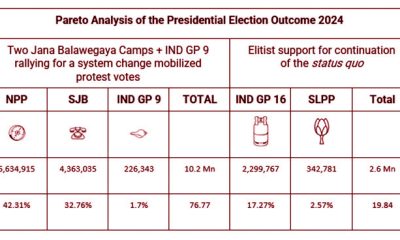

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake is not facing the possibility of being a cohabitation president. His NPP is generally expected to win at least a simple majority (113+) in parliament. A two-thirds majority will be a far shot. But the same pundits who described AKD as a ‘minority president’ because he did not get more than fifty percent of the votes or even a majority of the second and third preferential votes, are now worried that the NPP may end up getting a two-thirds majority of over 150 MPs in parliament. Their fears stem from the total disarray among the opposition parties.

Sajith Premadasa who lost his second presidential election in succession to different opponents, just like his bête noire Ranil Wickremesinghe in 1999 and 2005, pompously declared himself as the Prime Ministerial candidate for the parliamentary election. An absurd assertion that only shows how the presidential ethos has corroded the institution of parliament even as presidential powers have subordinated the legislature to the executive.

Mr. Premadasa has since gone quiet because of internal dissension and lack of any external traction. It is the same with every other political party. They are all in disarray. Disarrays that have long been in the making and have now come to pass. The NPP is not the cause but the fortuitous beneficiary of the overall opposition disintegration. Regardless of all the forebodings about an AKD presidency and an NPP government, Sri Lanka is better off having AKD and the NPP in government than any combination of all of the others who were in the last parliament. It is a breath of fresh air as some of have been saying. The challenge is to keep the new regime going the way it has been so far.

It is still too early to make sense of how the results of the parliamentary election will turn out. But based on the September presidential election results and accounting for proportional allocation of seats in the 22 electoral districts including the National List of 29 MPs, the NPP should get around 93 seats in parliament and that would be 20 short of a simple majority.

With the general enthusiasm around the NPP after the presidential election and the opposition disarray, the NPP could conceivably get an additional 20 seats for a simple majority. Getting to 150 seats will need an electoral tsunami. For comparison, in the 2020 parliamentary election, the SLPP polled 59% of the vote and obtained 145 seats. Within four years the SLPP and the Rajapaksas have gone from heroes to virtual zeros. So much for the impermanence of power and the fickleness of parliamentary sweeps.

Turning to the opposition candidates in September, the votes polled by Premadasa and Wickremasinghe respectively correspond to about 75 and 40 seats in parliament. But the vote totals of Premadasa and Wickremesinghe at the presidential election include significant proportions of votes from the Northern, Eastern and Central provinces and they will not accrue to the SJB and (Ranil’s) New Democratic Front in the parliamentary elections. So, the SJB and the NDF will get fewer seats than 75 and 40, respectively.

Overall, the opposition parties should be able to garner over 100 seats in the new parliament. That would be entirely because of the system of proportional representation, and it will not at all be reflective of the political vibes in the country. In a first past the post system, the NPP would win a landslide majority, like the United Front in 1970 and the UNP in 1977. But the people and the country are tired of both parliamentary tyrannies and presidential dictatorship. The NPP is promising something different.

The uncertainty is about voter turnout. In the presidential election, the voter turnout dropped by 5% from 84% in 2019 to 79%. For a second election in as many months, the turnout is likely to be even lower. The turnout was 76% for the 2020 parliamentary election, an 8% drop from the 2019 presidential election. Even though the Covid pandemic was a factor in 2020, it should not be surprising if the turnout for October 14 drops to be in the low 70s%. With the NPP the most organized for mobilizing its turnout, a low voter turnout overall will be disadvantageous to the opposition parties.

There is also election fatigue among the people. Elections of one form or another have been anticipated for nearly two years ever since aragalaya drove Gotabaya Rajapaksa out of power. As interim president, Ranil Wickremesinghe tired everyone by playing games with election timing until he could not do anything about the timing of the presidential election. Ideally, the two elections could and should have been held together. That may have even saved some political bacon for Mr. Wickremesinghe. But he was always too clever by half, but cleverness alone does not win elections.

Vice President Kamala Harris has been pitching her campaign with the slogan to ‘turn the page’ after a decade of Trumpian politics in the US. Whether or not she will succeed remains to be seen. But Sri Lanka has turned the page quite effortlessly, so to speak. The bigger task now is to start writing the next chapter. That should start the day after November 14.

Features

M.S. de Silva, Lanka’s first (successful) journalist/entrepreneur

The 23rd death anniversary of M.S. de Silva, the only Lankan journalist in my memory, who left journalism and carved out a business empire, falls on Oct. 29. His daughter, Nilupul, wanted me to run something about this ever smiling man, always in his trademark whites, who never forgot his friends whatever heights he scaled.

Immensely proud of his southern roots, he was one of the many entrepreneurs in this country, born south of the Bentara river, who made a name for himself as a business baron. This, like others of his ilk, he did with very little seed capital of his own, making and losing a fortune but never demonstrating the slightest trace of bitterness. When I was made the editor of what was then the Ceylon Daily News in the early eighties, he rang to congratulate me and tell me, rightly or wrongly, that I was the first southerner to get there.

MS, as I wrote some time ago on his 90th birth anniversary that fell on April 18, 2019, cut his journalistic teeth in the once British-owned Times of Ceylon which together with the Associated Newspapers of Ceylon Ltd., or Lake House as it was (and is) best known, dominated the news industry in the colonial days and well into the post-Independence period. He then moved to Radio Ceylon, and the Government Information Department probably for the security of a pensionable government job, and was assigned by the department to the Trade Ministry under Mr. T.B. Ilangaratne, a veteran left-inclined politician.

Older readers will remember that the Times, located in the Colombo Fort, once owned the country’s tallest building until Mr. Justin Kotelawela’s Ceylinco House rose some floors higher. All this is history today with Colombo’s skyline replete with high-rises dwarfing buildings of the mid-1950s. MS was one of a kind with a shock of curly hair, a broad smile that seldom left his face and a warm heart. He was ever ready to dig into his deep pockets to help his many friends in an ill-paid profession who were often broke.

Those were the days the Information Department was housed in what was previously the British High Commission in Colombo, a stone’s throw from Queen’s House. While the Director of Information sat in that building where the photographers and their darkroom as well as the necessary, though somewhat rudimentary, infrastructure was located, the press officers were assigned to various government ministries where they had offices but came to Queen’s Street for meetings with their bosses and other business.

I was probably requested me to write this because I am possibly the only journalist yet in harness who was privy to those days when MS was a press officer. Among his colleagues were several prominent newsmen of the day and names like BH Hemapriya, Kenneth Somanader, Dalton de Silva, UG Wimaladasa, HB Dissanayake and Victor Sumathipala come readily to mind.

As my late friend and colleague, Ajith Samaranayake, wrote some years ago in a piece on MS, these press officers had a strong foundation in journalism having begun their careers in newspaper publishing houses, and were well informed about the activities of the ministries to which they were assigned. They were not mere peddlers of handouts written by others or what we in the profession called “sunshine stories” (not about what has been done but what is going to be done often on the never never) and hurrah boys of their ministers ever-hungry for publicity, then as much as now.

I know that his family was not altogether happy that MS was giving up the security of a government job to get into business, but MS had Minister Ilangaratne’s assurance that he could always come back if things didn’t work out. Like Ilangaratne, MS too was left-inclined and was proud that he, as a 14-year old teenager, had been the legendary Communist Pieter Keuneman’s interpreter at a political meeting in the south when Keuneman was not as fluent in Sinhala as he later became. There was a news clip of a photograph of that meeting that MS treasured.

His plunge into business was perhaps inspired by his genes. Although MS was orphaned at the age of 12, his father like many from Galle, had struck out to Malaya setting up a business in Penang. Fate was kind to MS and his Trade Exchange (Ceylon) Ltd., across Chatham Street from the Pagoda Tea Rooms. His was among the first companies that traded with China and the business proved a success. I remember him importing a Chinese bike, branded Phoenix, at a time Raleigh was king, which he could price very competitively. He was also among the first to export coconut seedlings to Cuba.

It was Trade Exchange that set up Laklooms, one of the early batik brands with a showroom on Galle Road, Bambalapitiya, close to the Green Cabin. His wife, Karuna, stamped her own personality on the batik business which also prospered. The proximity of both their father’s offices to two landmark Rodrigo Restaurants was a bonus to MS’s children with easily procurable treats just across the road, his daughter tells me.

I remember attending Press Officer Hemapriya’s wedding at MS’s home at Raymond Road, Nugegoda, which MS and Karuna hosted. Karuna made the cake and the reception, befitting the host’s southern origins, was lavish with old friends from his newspaper and Information Department days present. Nimal Karunatillake’s wife, Chandra, very much a part of the journalist/press officer circuit at that time, whom I drove to the reception, called that house “MS’s palace.”

He moved from there to Rosemead Place, Colombo-7 when the gods continued smiling down on him. But good times were not for ever and for reasons I never knew MS hit hard times and had to fight a protracted case against the People’s Bank, which went on for years. He won both the case and the appeal the bank instituted and asked me to publish the results.

MS died prematurely at 70-years and his family believes that these travails shortened his life. He faced adversity stoically and success never went to his head.

May he attain nibbana.

Manik De Silva

Features

An important strategy to mitigate elephant-vehicle collisions

by Tharindu Muthukumarana

tharinduele@gmail.com

(Author of the award-winning book “The Life of Last Proboscideans: Elephants”)

According to a report by the World Bank, Sri Lanka has the highest road density in South Asia. On the other hand, Sri Lanka is a country with rich biodiversity and wildlife-collisions with trains/motorists have been there for aeons without a successful mitigating measure. This can risk the lives of wildlife as well as motorists or passengers. The latest one happened on October 18, 2024, in which two wild elephants died and two others were injured in a Batticaloa-bound fuel tanker train accident.

When considering train accidents, the best solutions would be an underground railway-transit line in wildlife-sensitive areas. But considering the economic status of the country, such projects can be difficult to initiate in the near future. So, this article proposes a strategy that can be implemented just within a few days and has a strong potential to at least mitigate the issue.

Deployment of patrols on roads where elephants roam

One place in Sri Lanka where elephants frequently cross the road is on the A11 road, which adjoins Minneriya National Park (NP). It must be remembered that Minneriya NP is famous for the seasonal gathering of elephants, which happens from July-September and is also titled the “largest gathering of Asian elephants.” During that season, elephants move to Minneriya NP from other protected areas. Apart from its’ ecological significance, it is also an economic asset since, according to wildlife tourism expert Mr. Srilal Miththapala, the direct and indirect tourism revenue of the Minneriya elephant gathering in 2018 was Rs. 8.7 billion (USD 52 million).

However, there is an effective method that can probably help to mitigate this issue to a greater extent, and that is none other than surveillance on the road. An analogous archetype is done on India’s National Highway 37, which cuts through the Kaziranga NP in Assam. Between July and August, due to the monsoon, a major part of the national park gets submerged because of the River Brahmaputra’s increased water level. As a result, animals are forced to migrate to higher elevations and forests outside the park’s southern border, including the Mikir Hills. But they have to cross the busy highway that cuts through Kaziranga and the hills. During that time period, forest guards patrol the highway both day and night by monitoring the speed of the vehicles, the behaviour of the motorists, and assisting animals wanting to cross the route.

Now the other question that pops up is, ‘Can that strategic method helps Sri Lanka, and to what extent’? The answer to that question is that there is high potential that it can be successful in mitigating. An exemplary reason comes from the Buttala-Kataragama road (B035) and Habarana road (A11).

B035 elephants are more likely to solicit food from motorists, standing in the middle of road pathways for extended periods, whereas A11 elephants are less likely to do so. However, A11 elephants have a higher mortality rate due to vehicle collisions, indicating that those not interested in road-soliciting are more likely to be knocked over.

This is because most motorists on B035 are aware of begging elephants that stand from place to place, blocking the pathway similar to security checkpoints, and as a result of this, motorists expect to encounter an elephant at any time. This leads to early detection, which triggers quick responses. In contrast, at A11, some motorists may be less expecting to encounter elephants, especially in the middle of the road. As a result of it, there can be a slow response. It is scientifically proven that attentional concentration leads to quicker brain processing and responding. Therefore, the points presented here are scientifically possible. Hence, what is left is to find the probability, and to do that, the proposed strategy has to be put into an experiment.

Another factor that may have changed the perception of the motorist is the difference between the surrounding environments of the B035 and the A11. The side of A11road has more human-interfering features, while B035 has more natural features. Thus, the higher natural features in B035 than in A11 might influence B035 motorists’ expectations of elephants.

Deployment of patrols at railways and its efficacy

Where the railway is concerned, in places where there are elephants there is a recommended speed limit, which is 20 kmph, and those are indicated with special sign boards. So, deployment of patrols with speed guns near railway tracks to check whether trains breach the speed limit in wildlife-sensitive areas is also important. Even in the recent event of the elephant collision, there is evidence that the train went beyond the recommended speed limits. The damage that had happened to the train and the railway track gives solid evidence of that

This proposed action is based on three reasons: (I) Because there have been incidents of train-elephant accidents due to breaches of speed limits. (II) According to elephant-train accidents’ statistical data, there is significant fluctuation from year to year. As experts suggest, this is because when elephants get knocked by a train, it creates a public uproar which results in trains conforming to the speed limits. But as time passes, when the uproar fades, again elephant-train collissions rise. (III) According to the available data, most elephants that get knocked down by trains are females. This is because females move in herds; and when they are crossing the railway track one behind the other, it can take longer time to cross the railway.

Besides, in many places where such accidents have occurred, the terrain has ‘slopes’ on either side or on one side of the railway line. When an animal of 5,221 kg – 3,465 kg moves in such a terrain, their gait obviously becomes slow. So, driving the train at a lower speed delays the time for the train to knock on the elephant.

Consequently, by deploying patrols from random distances, just similar to Kaziranga’s Highway, there can be some hope of mitigating elephant-vehicle collisions. Because locomotive drivers’/motorists’ perception of encountering checkpoints will be high, then they will, as a result, have a more effective response. Nevertheless, it also has the potential to tackle wildlife crimes that take place in ecologically sensitive areas. Furthermore, it is equally essential to deploy patrols with speed guns on railway tracks.

In conclusion, the presented points are scientifically feasible, but the next step is to determine the probability through an experiment. Usually, when these kinds of events occur, they become critical topics, but as time goes on, people forget about them, and the same fate repeats itself. So, let’s make this time an exception and cease the repetition.

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoA Pareto analysis of ‘Jana Balawegaya’ force

-

Editorial3 days ago

Editorial3 days agoProbe reports, skewed logic and emerging threats

-

Foreign News4 days ago

Foreign News4 days agoLee Hsien Yang, youngest son of Singapore founder, claims asylum in the UK

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoGammanpila challenges Minister Herath over allegations against former judge

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoSri Lanka riding high on an impressive run

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRelevance of a neutral foreign policy

-

Editorial2 days ago

Editorial2 days agoAcid test of leadership

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoIllegally assembled Johnny’s BMW bears engine & chassis numbers of car stolen in England in 2021 – Police