Midweek Review

Brecht’s Chalk Circle Again and Again

Azdak’s Judgments:

by Laleen Jayamanne

Soldier: Your Honour, we meant no harm. Your Honour, what do you wish?

Azdak: Nothing, fellow dogs. Or just an occasional boot to lick!

[…]

Fetch me wine, red wine, sweet red wine.

‘In a faraway and long-ago, dark and bloody epoch, in a sunburnt and cursed city, there lived a Duke…’ sang the storyteller. In the mid-’60s when Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle was first performed there, Colombo had ceased being dark and bloody. April ‘71 was yet a few years away. But the effects of the Sinhala Only Act of ‘56 were taking root in educational institutions, like the National School of Art and Crafts, creating a myopic, monolingual culture. In this context, Henry Jayasena and others in the Sinhala theatre who were interested in developing contemporary drama, began to translate modern European plays, originally written in German, Russian and Italian. Crucially, these Sinhala versions were drawn from English translations of the original languages of the plays. So English worked as the essential ‘link’ language without which we would not have had any access to world theatre and much else. Henry had a good command of English, learnt in high school and at Teachers’ College. Like his similarly brilliant contemporary Sugathapala de Silva, he was not a University educated artist. But Jayasena’s superb theatrical imagination allowed him to translate from English the Chalk Circle into a most wonderful colloquial poetic Sinhala idiom. So much so that it feels like the play was written originally in Sinhala! Reading the Sinhala script was a pleasure in itself and sections have remained in my old brain, as good poetry does. The epic techniques of supple shifts from the songs of the narrator, to the every-day racy, bawdy dialogue of the soldiers, to the lyrical love passages between Grusha and Simon Shashava, to the absurdist folk utterances of Azdak, are all memorably crafted and differentiated.

Bertolt Brecht’s Epic play written in 1944 while he was in exile in the US, fleeing Hitler’s fascist Germany, continues to be a vibrant part of Lanka’s living ‘theatrical epic-memory’. Also, as a text for the O’Level, a large number of Lankans must have become familiar with it. The play has a ‘play-within-a-play’ double structure but in scene 4, Azdak’s story, there is a further third level. That is, a ‘play-within-a play-within-a play’. The first play is set in the present postwar Soviet Republic of Georgia in 1945, where workers of two Collective Farms meet with a State official to decide, through discussion, as to who should have the stewardship of a particular valley. The Farmers who have been in the valley since birth claim it as their own for their goats to graze in, while the other group say that through irrigation they can make the valley more productive of fruit and wine. Its key question is, ‘who is good for the land?’

The play-within the play, set in the Imperial past of a fictional Georgia or Grusinia, at war with Persia. The folk parable of the Chalk Circle is performed as entertainment after the debate about the valley has been reasonably decided. The key question there becomes, ‘who is the good mother for the child?’ – (hadu mavada, vadu mavada? The third level of a play-within a play-within a play is a mock trial between a prince who wants to be the Judge and Azdak pretending to be the deposed Grand Duke, as the defendant. In all there are six or seven judgments that involve Azdak in one way or another. The intricacies of each of these legal cases and their differences from each other, make scene 4 a most fascinating aspect of the episodic structure of the play itself. In contrast, scenes 1-3 involving Grusha the kitchen-hand and her dilemma are expressed memorably and clearly by the narrator: “Terrible is the temptation to be good.” This is Grusha’s decision to save and nurture the Governor’s abandoned infant, without counting the terrible cost to herself. Her scenes, engaging as they are, do not have the kind of intricacy and complexity of the six or so episodes where Azdak plays with several ideas of Law and of Justice.

Animals’ Rights and the Folk Imagination

An Epic Contest is staged in the play, between the idea of The Law as a written code by absolutist rulers, and ideas of Social Justice, which include a sense of fairness towards the poor and powerless. This ample human feeling of fairness is encoded in folk tales of peoples across Eurasia where animals also have a claim on Justice from humans. For example, the Mahavamsa tells us of the remarkable sense of justice embodied by the Tamil King Elara when he ruled Anuradhapura. He had a bell hung at his palace gate, which anyone could ring to make a claim when an injustice had been committed. So, when a cow complained to Elara that his son in his chariot had run over and killed her calf, he did not hesitate to put his son to death. We are told that taking pity on them, both lives were restored by a god. According to my friend Amrit MacIntyre who is a lawyer and legal scholar that story is found in various forms in the Middle East to Europe. Each version of the story is about a king from the distant past who is known for his justice. Critically, in each version the person seeking justice was an animal, a serpent in Italy seeking justice from Charlemagne, and an ass in the Middle East seeking justice from an Iranian Emperor (Khusro I). What is intriguing in all of this is a common conception of justice equally applying to all, including animals, that forms part of the mental landscape across Eurasia from very early on. Interestingly, a 2017 decision of the Supreme Court of India referred to the story of Elara as part of its reasoning! The folk tale of the Chalk Circle is found in an ancient Chinese play, as well as in the Judgment of Solomon in the Old Testament, and both were points of reference for Brecht in radically rewriting the tale as a modern epic parable influenced by Marxist ideas.

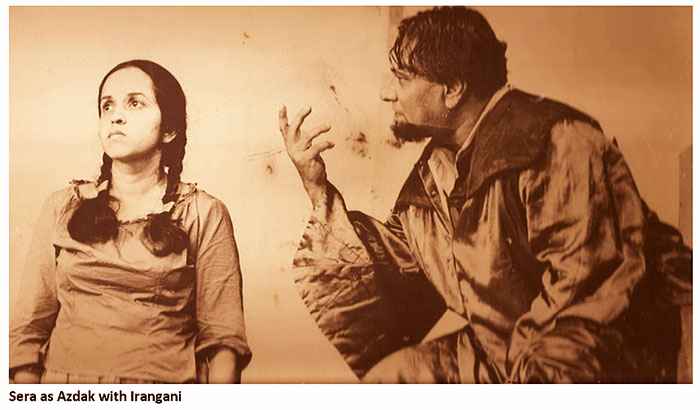

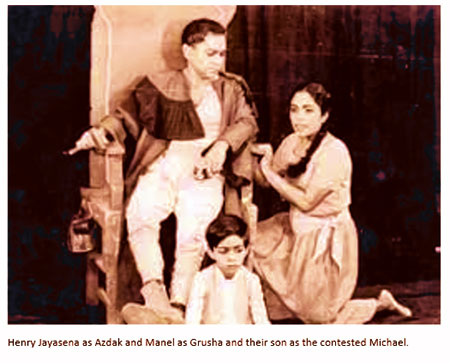

Azdak, the town scribe and rogue judge, was played memorably by Winston Serasinghe in Ernest MacIntyre’s English production. Henry Jayasena played the same in his own production, also in the mid-60s. And MacIntyre also acted as the priest in Henry’s production – one of the earliest exchanges between English and Sinhala Theatre in the ‘60s. That is to say, between the Lionel Wendt and Lumbini theatres, respectively. Azdak was the village scribe who, when the State collapsed and the official judge hanged by the rebellious carpet weavers, was forcibly roped in to act as a judge by the illiterate soldiers. But it turned out that he had his own eccentric ideas of Justice and fair play and was a bit drunk, sexist and openly took money from plaintiffs. Though Azdak appears only in the last 2 scenes, he leaves a powerful impression in one’s memory as a character like Shakespeare’s Falstaff. But he is unlike Falstaff whose fall from grace, after rejection by his former buddy Prince Hal, is full of tragic pathos. Azdak is a creature of the folk imagination.

Epic-Character Azdak

Sumathy Sivamohan concludes her recent article on the links between the two Republican Constitutions of Sri Lanka (‘72 & ‘78), by invoking Azdak as a figure relevant to this moment of the People’s Aragalaya, (The Island 8/8). Azdak is a Brechtian Epic-Character through whom the very ideas of Law and Justice are examined, played with, debated and put into crisis, theatrically. He is also a great comic figure introducing laughter into the court where it is thought to be unseemly. In this way Brecht’s Epic Theatrical practice offers us several unusual angles on the process of making Judgements, the reasoning behind them. Through these scenes, the idea of Justice appears paradoxical, not altogether just in one case, but also both reasonable and yet ‘unlawful’, if judged according to the letter of the Law, in another. And some downright absurd. This complexity, of plot lines and intricacy of comic procedural ‘legal’ detail, is significant in demonstrating the class basis of judgements and how they are reached. The hilarious comic absurdity of some of Azdak’s arguments and rulings parody seemingly rational, legalistic linguistic power-play in regular courts. ‘Demonstrability’ is a strong concept in Brechtian theatrical theory and is linked to the idea of the pedagogical function of Epic Theatre.

A Brechtian Parable for the Aragalaya?

The comedic demonstration of the interplay between the Law and Justice, appears to be relevant to Lankans now, poised in their struggle to make politicians accountable for their actions which have plunged the country into economic, political and existential chaos. Azdak is an epic construct and as such we don’t quite empathise with him or like or dislike him. Rather, we observe this comic figure with enjoyment, as he plays with a variety of judgments, with no rule book as guide. He excites our curiosity about the mechanics of the Law, its different avatars, (Totalitarian Law, People’s Law, a judgment without a precedent), which, in an Imperial regime, as in the world of the play within the play, seems invincible and arbitrary. The two lawyers of the Governor’s wife Natella Abashvili are, however, immediately recognisable social types aligned with social power, contrasting with Azdak’s Epic singularity. They argue for the right of the blood-line to obtain the child from Grusha, to return to his biological but callous and predatory mother, only so that she can claim the property bequeathed to the child.

A Palace Revolution

The Chalk Circle opens on a seemingly normal Easter Sunday, with the wealthy Governor and family attending church to great fanfare that soon turns violent – palace revolution creates chaos and soldiers go to war against distant Persia. The Governor is beheaded, his head impaled on a lance and displayed, nailed to a wall, while his wife flees forgetting to take their baby. The Grand Duke has also gone into hiding. The Carpet Weavers, taking advantage of the revolt, hang the Judge. So it comes to pass that the village scribe Azdak becomes the accidental Judge, under a state of emergency. Not knowing the Law is no impediment to Azdak. Some of these events and scenes of the play have an uncanny resemblance to the farcical misrule seen in the Lankan Parliament not too long ago. Before we look at Azdak’s celebrated Judgments it’s worth looking at Brecht’s original theatrical structure, which is Epic rather than Dramatic.

Epic Theatre vs Tragic Drama

Brecht’s play is not a tragedy, a genre he rejected as an Aristotelian Greek notion driven by an idea of Destiny and causality and heroic action. The presence of a singer-narrator who introduces us to the play is an epic device in that, as the story-teller, he conducts the action. He stops characters in their tracks and sings of what they feel, but cannot say. He explains the action when necessary and advances the story. The famous singer who knows twenty-one thousand lines of verse becomes the story-teller. He announces that the play consists of ‘two stories and will take two hours to perform’. The Soviet expert from the city is impatient and asks him, (after the disagreement between the two collective farmers is resolved), “can’t you make it shorter?” The singer responds with a firm ‘No’. Brecht offers a play, which is profoundly episodic in its construction. Each episode is autonomous, has a relative freedom from a tight causally driven dramatic structure. What Brecht wanted was a theatrical structure which didn’t have any inevitable causal links propelling events as in the case of, say, Oedipus Rex. In this way he demonstrates how History and its presentation in the Epic, hold alternative possibilities. The Epic form can reveal in its episodic structure ‘the many roads not taken’. Some academics in the Aragalaya have begun to examine Lanka’s post independent history and the many roads not taken in structuring the economy, in race relations and education and development policy, for instance.

Brecht’s play is not a tragedy, a genre he rejected as an Aristotelian Greek notion driven by an idea of Destiny and causality and heroic action. The presence of a singer-narrator who introduces us to the play is an epic device in that, as the story-teller, he conducts the action. He stops characters in their tracks and sings of what they feel, but cannot say. He explains the action when necessary and advances the story. The famous singer who knows twenty-one thousand lines of verse becomes the story-teller. He announces that the play consists of ‘two stories and will take two hours to perform’. The Soviet expert from the city is impatient and asks him, (after the disagreement between the two collective farmers is resolved), “can’t you make it shorter?” The singer responds with a firm ‘No’. Brecht offers a play, which is profoundly episodic in its construction. Each episode is autonomous, has a relative freedom from a tight causally driven dramatic structure. What Brecht wanted was a theatrical structure which didn’t have any inevitable causal links propelling events as in the case of, say, Oedipus Rex. In this way he demonstrates how History and its presentation in the Epic, hold alternative possibilities. The Epic form can reveal in its episodic structure ‘the many roads not taken’. Some academics in the Aragalaya have begun to examine Lanka’s post independent history and the many roads not taken in structuring the economy, in race relations and education and development policy, for instance.

Azdak’s Judgements

Why do I think that a ‘close reading’ of Azdak’s judgements matter, especially now? Because he has a window of opportunity during a palace revolution, to play with and interrogate ideas of Law and Justice. It is quite by chance that he is made a judge because the official judge has been hanged, the Governor executed and the Duke has fled during the civil war. Now is a time when a large number of people in Lanka are feeling that the Laws that govern them and their sense of Justice are at variance. And Azdak’s idiosyncratic process of judging and his rulings offer several unusual angles on both. He is unprincipled and we can’t tell which way his Judgment will fall, regardless of his own precedent. He is inconsistent but not amoral, he shows feelings on the bench, he is not ‘Blind Justice’. He has a strong conscience. Guilt-ridden, he has himself arrested and shackled by Sauwa the cop, for having unwittingly given the fugitive Grand Duke refuge in his hut and helped him escape, during the palace revolution.

In the mock trial Azdak impersonates the Grand Duke. The soldiers who call the shots say they want to test if the Nephew is fit and proper to be a judge as recommended by his uncle Prince Kazbeki. So they create a legal play within the play by making Azdak play the role of the Grand Duke as the defendant and the Nephew the acting judge. Azdak as the Grand Duke is accused of losing the war and in his comic defense he demonstrates how the Princes actually won by war-profiteering and enabling the Persians victory. All this is done in a brilliant quick-witted, punchy question and answer session where Azdak twists words and wins the argument with relish. Proven guilty of embezzlement, the soldiers arrest the acting judge and Prince Kazbeki and plonk Azdak on the throne, unceremoniously throwing the cloak of the dead judge across his shoulders. It’s high farce with linguistic fireworks in court.

A judgement Azdak makes from the bench deals with a farmer’s complaint against his farmhand who is accused of raping his daughter-in-law, Ludovica. By contemporary feminist standards Azdak’s judgment that Ludovica by virtue of her seductive walk, seduced and thereby ‘raped’ the man, is idiotic and sexist. But the scene is more ambiguous. It might be the case that what was called rape by the father-in-law may have been consensual sex, which he happened to stumble in on. We are told by the narrator that the Ludovica’s speech was well rehearsed. The scene remains ambiguous, open to several readings especially because Azdak orders Ludovica to accompany him to examine the scene of the crime after the verdict has found her guilty! The narrator has called him, ‘Good judge, bad judge, Azdak.’

Another judgment shows that Azdak is indeed a ‘people’s judge,’ ruling in favour of a grandmotherly old woman, against the three farmers who accuse her of theft. The old woman wins the case by virtue of being poor, despite the fact that the items were stolen on her behalf by a relative who is a Bandit. The plea she offers in her defense is her belief in miracles. So, taking up her cue Azdak reprimands the Farmers for not believing in miracles! To save time, Azdak decides to hear two similar cases of professional negligence and blackmail, together!

The judgment of the Chalk Circle is what Azdak is most famous for. But the previous ones, with their pileup of parodic absurdity, are crucial for Brecht’s politics in Demonstrating how social class, wealth and power determine legal ritual. Once the normality of the Grand Duke’s authoritarian rule is restored, Prince Kazbeki is beheaded as a traitor. The chaos of the revolutionary moment (‘a Golden age’?) that saw Azdak become a judge, with his own unique sense of justice, is reversed with the return of the Grand Duke. He is now attacked by the illiterate soldiers, bloodied and humiliated, soon to be hanged. But at the last moment a messenger from the Grand Duke arrives with a document ordering Azdak to be exonerated and made judge for having saved the Duke’s life. It is jarring to register that the Grand Duke does have a sense of aristocratic honour (unlike Lanka’s rulers) despite his reputation as a swindler and butcher.

Azdak wipes the blood from his eyes as he finds himself plonked on the judges’ chair yet again, and makes the celebrated progressive modern judgment of the Chalk Circle. It is reached through an ingenious process based on an ancient wordless contest. Grusha repeatedly refuses to pull the child out of the circle lest he be injured and so she is deemed the ‘true’ mother and given custody of the child, against the predatory biological mother who pulls him out. The singer then concludes the epic parable with a poetic summary of how Azdak aligned a feeling of Justice with eminently reasonable new rules. In that legal thinking, human emotion becomes the sister of rational thought.

Singer:

“The people of Georgia

Remembered him, and remembered

For a long time,

The times when he was judge

As a short, golden age

When there was justice – nearly.

Take to heart,

All you who’ve heard

The Tale of the Chalk Circle

And what that ancient song means.

What there is should belong

To those who are good at it.

Children to true mothers,

That they may thrive.

Carts to the good drivers,

That they may be driven well,

And the valley to the waterers,

So that it bears fruit.”

Sri Lanka is a country in which Chalk Circle has been seen and enjoyed for generations. Doing a close reading of the play, while following the non-violent political uprising and struggle of the people from afar, gives one hope that changes good for Lanka are imaginable so that the land may bear fruit.

Midweek Review

Year ends with the NPP govt. on the back foot

The failure on the part of the Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna (JVP)-led National People’s Power (NPP) government to fulfil a plethora of promises given in the run up to the last presidential election, in September, 2024, and a series of incidents, including cases of corruption, and embarrassing failure to act on a specific weather alert, ahead of Cyclone Ditwah, had undermined the administration beyond measure.

Ditwah dealt a knockout blow to the arrogant and cocky NPP. If the ruling party consented to the Opposition proposal for a Parliamentary Select Committee (PSC) to probe the events leading to the November 27 cyclone, the disclosure would be catastrophic, even for the all-powerful Executive President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, as responsible government bodies, like the Disaster Management Centre that horribly failed in its duty, and the Met Department that alerted about the developing storm, but the government did not heed its timely warnings, directly come under his purview.

The NPP is on the back foot and struggling to cope up with the rapidly developing situation. In spite of having both executive presidency and an overwhelming 2/3 majority in Parliament, the government seems to be weak and in total disarray.

The regular appearance of President Dissanayake in Parliament, who usually respond deftly to criticism, thereby defending his parliamentary group, obviously failed to make an impression. Overall, the top NPP leadership appeared to have caused irreparable damage to the NPP and taken the shine out of two glorious electoral victories at the last presidential and parliamentary polls held in September and November 2024 respectively.

The NPP has deteriorated, both in and out of Parliament. The performance of the 159-member NPP parliamentary group, led by Prime Minister Dr. Harini Amarasuriya, doesn’t reflect the actual situation on the ground or the developing political environment.

Having repeatedly boasted of its commitment to bring about good governance and accountability, the current dispensation proved in style that it is definitely not different from the previous lots or even worse. (The recent arrest of a policeman who claimed of being assaulted by a gang, led by an NPP MP, emphasised that so-called system change is nothing but a farce) In the run-up to the November, 2024, parliamentary polls, President Dissanayake, who is the leader of both the JVP and NPP, declared that the House should be filled with only NPPers as other political parties were corrupt. Dissanayake cited the Parliament defeating the no-confidence motions filed against Ravi Karunanayake (2016/over Treasury Bond scams) and Keheliya Rambukwella (2023/against health sector corruption) to promote his argument. However, recently the ongoing controversy over patient deaths, allegedly blamed on the administration of Ondansetron injections, exposed the government.

Mounting concerns over drug safety and regulatory oversight triggered strong calls from medical professionals, and trade unions, for the resignation of senior officials at the National Medicines Regulatory Authority (NMRA) and the State Pharmaceutical Corporation (SPC).

Medical and civil rights groups declared that the incident exposed deep systemic failures in Sri Lanka’s drug regulatory framework, with critics warning that the collapse of quality assurance mechanisms is placing patients’ lives at grave risk.

The Medical and Civil Rights Professional Association of Doctors (MCRPA), and allied trade unions, accused health authorities of gross negligence and demanded the immediate resignation of senior NMRA and SPC officials.

MCRPA President Dr. Chamal Sanjeewa is on record as having said that the Health Ministry, NMRA and SPC had collectively failed to ensure patient safety, citing, what he described as, a failed drug regulatory system.

The controversy has taken an unexpected turn with some alleging that the NPP government, on behalf of Sri Lanka and India, in April this year, entered into an agreement whereby the former agreed to lower quality/standards of medicine imports.

Trouble begins with Ranwala’s resignation

The NPP suffered a humiliating setback when its National List MP Asoka Ranwala had to resign from the post of Speaker on 13 December, 2024, following intense controversy over his educational qualification. The petroleum sector trade union leader served as the Speaker for a period of three weeks and his resignation shook the party. Ranwala, first time entrant to Parliament was one of the 18 NPP National List appointees out of a total of 29. The Parliament consists of 196 elected and 29 appointed members. Since the introduction of the National List, in 1989, there had never been an occasion where one party secured 18 slots.

The JVP/NPP made an initial bid to defend Ranwala but quickly gave it up and got him to resign amidst media furor. Ranwala dominated the social media as political rivals exploited the controversy over his claimed doctorate from the Waseda University of Japan, which he has failed to prove to this day. But, the JVP/NPP had to suffer a second time as a result of Ranwala’s antics when he caused injuries to three persons, including a child, on 11 December, in the Sapugaskanda police area.

The NPP made a pathetic, UNP and SLFP style effort to save the parliamentarian by blaming the Sapugaskanda police for not promptly subjecting him for a drunk driving test. The declaration made by the Government Analyst Department that the parliamentarian hadn’t been drunk at the time of the accident, several days after the accident, does not make any difference. Having experienced the wrongdoing of successive previous governments, the public, regardless of what various interested parties propagated on social media, realise that the government is making a disgraceful bid to cover-up.

No less a person than President Dissanayake is on record as having said that their members do not consume liquor. Let us wait for the outcome of the internal investigation into the lapses on the part of the Sapugaskanda police with regard to the accident that happened near Denimulla Junction, in Sapugaskanda.

JVP/NPP bigwigs obviously hadn’t learnt from the Weligama W 15 hotel attack in December, 2023, that ruined President Ranil Wickremeinghe’s administration. That incident exposed the direct nexus between the government and the police in carrying out Mafia-style operations. Although the two incidents cannot be compared as the circumstances differ, there is a similarity. Initially, police headquarters represented the interests of the wrongdoers, while President Wickremesinghe bent over backwards to retain the man who dispatched the CCD (Colombo Crime Division) team to Weligama, as the IGP. The UNP leader went to the extent of speaking to Chief Justice Jayantha Jayasuriya, PC, and Speaker Mahinda Yapa Abeywardena to push his agenda. There is no dispute the then Public Security Minister Tiran Alles wanted Deshabandu Tennakoon as IGP, regardless of a spate of accusations against him, in addition to him being faulted by the Supreme Court in a high-profile fundamental rights application.

The JVP/NPP must have realised that though the Opposition remained disorganised and ineffective, thanks to the media, particularly social media, a case of transgression, if not addressed swiftly and properly, can develop into a crisis. Action taken by the government to protect Ranwala is a case in point. Government leaders must have heaved a sigh of relief as Ranwala is no longer the Speaker when he drove a jeep recklessly and collided with a motorcycle and a car.

Major cases, key developments

Instead of addressing public concerns, the government sought to suppress the truth by manipulating and exploiting developments

* The release of 323 containers from the Colombo Port, in January 2025, is a case in point. The issue at hand is whether the powers that be took advantage of the port congestion to clear ‘red-flagged’ containers.

Although the Customs repeatedly declared that they did nothing wrong and such releases were resorted even during Ranil Wickremesinghe’s presidency (July 2022 to September 2024), the public won’t buy that. Container issue remains a mystery. That controversy eroded public confidence in the NPP that vowed 100 percent transparency in all its dealings. But the way the current dispensation handled the Port congestion proved that transparency must be the last thing in the minds of the JVPers/NPPers holding office.

* The JVP/NPP’s much touted all-out anti-corruption stand suffered a debilitating blow over their failure to finalise the appointment of a new Auditor General. In spite of the Opposition, the civil society, and the media, vigorously taking up this issue, the government continued to hold up the appointment by irresponsibly pushing for an appointment acceptable to President Dissanayake. The JVP/NPP is certainly pursuing a strategy contrary to what it preached while in the Opposition and found fault with successive governments for trying to manipulate the AG. It would be pertinent to mention that President Dissanayake should accept the responsibility for the inordinate delay in proposing a suitable person to that position. The government failed to get the approval of the Constitutional Council more than once to install a favourite of theirs in it, thanks to the forthright position taken by its civil society representatives.

The government should be ashamed of its disgraceful effort to bring the Office of the Auditor General under its thumb:

* The JVP/NPP government’s hotly disputed decision to procure 1,775 brand-new double cab pickup trucks, at a staggering cost exceeding Rs. 12,500 mn, under controversial circumstances, exposed the duplicity of that party that painted all other political parties black. Would the government rethink the double cab deal, especially in the wake of economic ruination caused by Cyclone Ditwah? The top leadership seems to be determined to proceed with their original plans, regardless of immeasurable losses caused by Cyclone Ditwah. Post-cyclone efforts still remain at a nascent stage with the government putting on a brave face. The top leadership has turned a blind eye to the overwhelming challenge in getting the country back on track especially against the backdrop of its agreement with the IMF.

Post-Cyclone Ditwah recovery process is going to be slow and extremely painful. Unfortunately, both the government and the Opposition are hell-bent on exploiting the miserable conditions experienced by its hapless victims. The government is yet to acknowledge that it could have faced the crisis much better if it acted on the warning issued by Met Department Chief Athula Karunanayake on 12 November, two weeks before the cyclone struck.

Foreign policy dilemma

Sri Lanka moved further closer to India and the US this year as President Dissanayake entered into several new agreements with them. In spite of criticism, seven Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs), including one on defence, remains confidential. What are they hiding?

Within weeks after signing of the seven MoUs, India bought the controlling interests in the Colombo Dockyard Limited for USD 52 mn.

Although some Opposition members, representing the SJB, raised the issue, their leader Sajith Premadasa, during a subsequent visit to New Delhi, indicated he wouldn’t, under any circumstances, raise such a contentious issue.

Premadasa went a step further. The SJB leader assured his unwavering commitment to the full implementation of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution that was forced on Sri Lanka during President JRJ’s administration, under the highly questionable Indo-Lanka Accord of July, 1987, after the infamous parippu drop by Indian military aircraft over Jaffna, their version of the old gunboat diplomacy practiced by the West.

Both India and the US consolidated their position here further in the post-Aragalaya period. Those who felt that the JVP would be in a collision course with them must have been quite surprised by the turn of events and the way post-Aragalaya Sri Lanka leaned towards the US-India combine with not a hum from our carboard revolutionaries now installed in power. They certainly know which side of the bread is buttered. Sri Lanka’s economic deterioration, and the 2023 agreement with the IMF, had tied up the country with the US-led bloc.

In spite of India still procuring large quantities of Russian crude oil and its refusal to condemn Russia over the conflict in Ukraine, New Delhi has obviously reached consensus with the US on a long-term partnership to meet the formidable Chinese challenge. Both countries feel each other’s support is incalculably vital and indispensable.

Sri Lanka, India, and Japan, in May 2019, signed a Memorandum of Cooperation (MoC) to jointly develop the East Container Terminal (ECT) at the Colombo Port. That was during the tail end of the Yahapalana administration. The Gotabaya Rajapaksa administration wanted to take that project forward. But trade unions, spearheaded by the JVP/NPP combine, thwarted a tripartite agreement on the basis that they opposed privatisation of the Colombo Port at any level.

But, the Colombo West International Terminal (CWIT) project, that was launched in November, 2022, during Ranil Wickremesinghe’s presidency, became fully operational in April this year. The JVP revolutionary tiger has completely changed its stripes regarding foreign investments and privatisation. If the JVP remained committed to its previous strategies, India taking over CDL or CWIT would have been unrealistic.

The failure on the part of the government to reveal its stand on visits by foreign research vessels to ports here underscored the intensity of US and Indian pressure. Hope our readers remember how US and India compelled the then President Wickremesinghe to announce a one-year moratorium on such visits. In line with that decision Sri Lanka declared research vessels wouldn’t be allowed here during 2024. The NPP that succeeded Wickremesinghe’s administration in September, 2024, is yet to take a decision on foreign research vessels. What a pity?

The NPP ends the year on the back foot, struggling to cope up with daunting challenges, both domestic and external. The recent revelation of direct Indian intervention in the 2022 regime change project here along with the US underscored the gravity of the situation and developing challenges. Post-cyclone period will facilitate further Indian and US interventions for obvious reasons.

****

Perhaps one of the most debated events in 2025 was the opening of ‘City of Dreams Sri Lanka’ that included, what the investors called, a world-class casino. In spite of mega Bollywood star Shah Rukh Khan’s unexpected decision to pull out of the grand opening on 02 August, the investors went ahead with the restricted event. The Chief Guest was President Anura Kumara Dissanayake, who is also the Finance Minister, in addition to being the Defence Minister. Among the other notable invitees were Dissanayake’s predecessor Ranil Wickremesinghe, whose administration gave critical support to the high-profile project, worth over USD 1.2 bn. John Keells Holdings PLC (JKH) and Melco Resorts & Entertainment (Melco) invested in the project that also consist of the luxurious Nüwa hotel and a premium shopping mall. Who would have thought President Dissanayake’s participation, even remotely, possible, against the backdrop of his strong past public opposition to gambling of any kind?

Don’t forget ‘City of Dreams’ received a license to operate for a period of 20 years. Definitely an unprecedented situation. Although that license had been issued by the Wickremesinghe administration, the NPP, or any other political party represented in Parliament, didn’t speak publicly about that matter. Interesting, isn’t it, coming from people, still referred by influential sections of the Western media, as avowed Marxists?

By Shamindra Ferdinando

Midweek Review

The Aesthetics and the Visual Politics of an Artisanal Community

Through the Eyes of the Patua:

Organised by the Colombo Institute for Human Sciences in collaboration with Millennium Art Contemporary, an interesting and unique exhibition got underway in the latter’s gallery in Millennium City, Oruwala on 21 December 2025. The exhibition is titled, ‘Through the Eyes of the Patua: Ramayana Paintings of an Artisanal Community’ and was organized in parallel with the conference that was held on 20 December 2025 under the theme, ‘Move Your Shadow: Rediscovering Ravana, Forms of Resistance and Alternative Universes in the Tellings of the Ramayana.’ The scrolls on display at the gallery are part of the over 100 scrolls in the collection of Colombo Institute’s ‘Roma Chatterji Patua Scroll Collection.’ Prof Chatterji, who taught Sociology at University of Delhi and at present teaches at Shiv Nadar University donated the scrolls to the Colombo Institute in 2024.

Organised by the Colombo Institute for Human Sciences in collaboration with Millennium Art Contemporary, an interesting and unique exhibition got underway in the latter’s gallery in Millennium City, Oruwala on 21 December 2025. The exhibition is titled, ‘Through the Eyes of the Patua: Ramayana Paintings of an Artisanal Community’ and was organized in parallel with the conference that was held on 20 December 2025 under the theme, ‘Move Your Shadow: Rediscovering Ravana, Forms of Resistance and Alternative Universes in the Tellings of the Ramayana.’ The scrolls on display at the gallery are part of the over 100 scrolls in the collection of Colombo Institute’s ‘Roma Chatterji Patua Scroll Collection.’ Prof Chatterji, who taught Sociology at University of Delhi and at present teaches at Shiv Nadar University donated the scrolls to the Colombo Institute in 2024.

The paintings on display are what might be called narrative scrolls that are often over ten feet long. Each scroll narrates a story, with separate panels pictorially depicting one component of a story. The Patuas or the Chitrakars, as they are also known, are traditionally bards. A bard will sing the story that is depicted by each scroll which is simultaneously unfurled. For Sri Lankan viewers for whom the paintings and their contexts of production and use would be unusual and unfamiliar, the best way to understand them is to consider them as a comic strip. In the case of the ongoing exhibition, since the bards or the live songs are not a part of it, the word and voice elements are missing. However, the curators have endeavoured to address this gap by displaying a series of video presentations of the songs, how they are performed and the history of the Patuas as part of the exhibition itself.

The unfamiliarity of the art on display and their histories, necessitates broader explanation. The Patua hail from Medinipur District of West Bengal in India. Essentially, this community of artisans are traditional painters and singers who compose stories based on sacred texts such as the Ramayana or Mahabharata as well as secular events that can vary from the bombing of the Twin Towers in New York in 2001 to the Indian Ocean Tsunami of 2004. Even though painted storytelling is done by a number of traditional artisan groups in India, the Patua is the only community where performers and artists belong to the same group. Hence, Professor Chatterji, in her curatorial note for the exhibition calls them “the original multi-media performers in Bengal.”

‘The story of the Patuas’ also is an account of what happens to such artisanal communities in contemporary times in South Asia more broadly even though this specific story is from India. There was a time before the 21st century when such communities were living and working across a large part of eastern India – each group with a claim to their recognizably unique style of painting. However, at the present time, this community and their vocation is limited to areas such as Medinipur, Birbhum, Purulia in West Bengal and Dumka in Jharkhand.

A pertinent question is how the scroll painters from Medinipur have survived the vagaries of time when others have not. Professor Chatterji provides an important clue when she notes that these painters, “unlike their counterparts elsewhere, are also extremely responsive to political events.” As such, “apart from a rich repertoire of stories based on myth and folklore, including the Ramayana and other epics, they have, over many years, also composed on themes that range from events of local or national significance such as boat accidents and communal violence to global events such as the tsunami and the attack on the World Trade Centre.”

There is another interesting aspect that becomes evident when one looks into the socio-cultural background of this community. As Professor Chatterji writes, “one significant feature that gives a distinct flavour to their stories is the fact that a majority of Chitrakars consider themselves to be Muslims but perform stories based largely on Hindu myths.” In this sense, their story complicates the tension-ridden dichotomies between ethno-cultural and religious groups typical of relations between groups in India as well as more broadly in South Asia, including in Sri Lanka. Prof Chatterji suggests this positionality allows the Patua to have “a truly secular voice so vital in the world that we live in today.”

As a result, she notes, contemporary Patuas “have propagated the message of communal harmony in their compositions in the context of the recent riots in India and the Gulf War. Their commentaries couched in the language of myth are profoundly symbolic and draw on a rich oral tradition of storytelling.” What is even more important is their “engagement with contemporary issues also inflects their aesthetics” because many of these painters also “experiment with novel painterly values inspired by recent interaction with new media such as comic books and with folk art forms from other parts of the country.”

From this varied repertoire of the Patuas’ painterly tradition, this exhibition focusses on scrolls portraying different aspects of the Ramayana. In North Indian and the more dominant renditions of the Ramayana, the focus is on Rama while in many alternate renditions this shifts to Ravana as typified by versions popular among the Sinhalas and Tamils in Sri Lanka as well as in some areas in several Indian states. Compared to this, the Patua renditions in the exhibition mostly illustrate the abduction of Sita with a pronounced focus on Sita and not on Ravana, the conventional antagonist or on Rama, the conventional protagonist. As a result, these two traditional male colossuses are distant. Moreover, with the focus on Sita, these folk renditions also bring to the fore other figures directly associated with her such as her sons Luv and Kush in the act of capturing Rama’s victory horse as well as Lakshmana.

Interestingly, almost as a counter narrative, which also serves as a comparison to these Ramayana scrolls, the exhibition also presents three scrolls known as ‘bin-Laden Patas’ depicting different renditions on the attack on New York’s Twin Towers.

While the painted scrolls in this collection have been exhibited thrice in India, this is the first time they are being exhibited in Sri Lanka, and it is quite likely such paintings from any community beyond Sri Lanka’s shores were not available for viewing in the country before this. Organised with no diplomatic or political affiliation and purely as a Sri Lankan cultural effort with broader South Asian interest, it is definitely worth a visit. The exhibition will run until 10 January 2026.

Midweek Review

Spoils of Power

Power comes like a demonic spell,

To restless humans constantly in chains,

And unless kept under a tight leash,

It drives them from one ill deed to another,

And among the legacies they thus deride,

Are those timeless truths lucidly proclaimed,

By prophets, sages and scribes down the ages,

Hailing from Bethlehem, Athens, Isipathana,

And other such places of hallowed renown,

Thus plunging themselves into darker despair.

By Lynn Ockersz

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoOfficials of NMRA, SPC, and Health Minister under pressure to resign as drug safety concerns mount

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoExpert: Lanka destroying its own food security by depending on imported seeds, chemical-intensive agriculture

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoFlawed drug regulation endangers lives