Features

A tribute to vajira

By Uditha Devapriya

The female dancer’s form figures prominently in Sinhalese art and sculpture. Among the ruins of the Lankatilake Viharaya in Polonnaruwa is a series of carvings of dwarves, beasts, and performers. They surround a decapitated image of a standing Buddha, secular figures dotting a sacred space. Similar figures of dancing women adorn the entrance at the Varaka Valandu Viharaya in Ridigama, adjoining the Ridi Vihare. Offering a contrast with carvings of men sporting swords and spears, they entrance the eye immediately.

A motif of medieval Sinhalese art, these were influenced by hordes of dancers that adorned the walls of South Indian temples. They attest to the role that Sinhala society gave women, a role that diminished with time, so much so that by the 20th century, Sinhalese women had been banned from wearing the ves thattuwa. Held back for long, many of these women now began to rebel. They would soon pave the way for the transformation of an art.

In January 2020 the government of India chose to award the Padma Shri to two Sri Lankan women. This was done in recognition not just of their contribution to their fields, but also their efforts at strengthening ties between the two countries. A few weeks ago, in the midst of a raging pandemic, these awards were finally conferred on their recipients.

One of them, Professor Indra Dissanayake, had passed away in 2019. Her daughter received the honour in her name in India. The other, Vajira Chitrasena, remains very much alive, and as active. She received her award at a ceremony at the Indian High Commission in Colombo. Modest as it may have been, the conferment seals her place in the country, situating her in its cultural landscape as one of our finest exponents of dance.

Vajira Chitrasena was far from the first woman to take up traditional dance in Sri Lanka. But she was the first to turn it into a full time, lifelong profession, absorbing the wellsprings of its past, transcending gender and class barriers, and taking it to the young. Dancing did not really come to her; it was the other way around. Immersing herself in the art, she entered it at a time when the medium had been, and was being, transformed the world over: by 1921, the year her husband was born, Isadora Duncan and Ruth St Denis had pioneered and laid the foundation for the modernisation of the medium. Their project would be continued by Martha Graham, for whom Vajira would perform decades later.

In Sri Lanka traditional dance had long turned away from its ritualistic past, moving into the stage and later the school and the university. Standing in the midst of these developments, Vajira Chitrasena found herself questioning and reshaping tradition. It was a role for which history had ordained her, a role she threw herself into only too willingly.

In dance as in other art forms, the balance between tradition and modernity is hard, if not impossible, to maintain. Associated initially with an agrarian society, traditional dance in Sri Lanka evolved into an object of secular performance. Under colonial rule, the patronage of officials, indeed even of governors themselves, helped free it from the stranglehold of the past, giving it a new lease of life that would later enable what Susan Reed in her account of dance in Sri Lanka calls the bureaucratisation of the arts. This is a phenomenon that Sarath Amunugama explores in his work on the kohomba kankariya as well.

Yet this did not entail a complete break from the past: then as now, in Sri Lanka as in India, dancing calls for the revival of conventions: the namaskaraya, the adherence to Buddhist tenets, and the contemplation of mystical beauty. It was in such a twilight world that Vajira Chitrasena and her colleagues found themselves in. Faced with the task of salvaging a dying art, they breathed new life to it by learning it, preserving it, and reforming it.

Though neither Vajira nor her husband belonged to the colonial elite, it was the colonial elite who began approaching traditional art forms with a zest and vigour that determined their trajectory after independence. Bringing together patrons, teachers, students, and scholars of dance, the elite forged friendships with tutors and performers, often becoming their students and sometimes becoming teachers themselves.

Though neither Vajira nor her husband belonged to the colonial elite, it was the colonial elite who began approaching traditional art forms with a zest and vigour that determined their trajectory after independence. Bringing together patrons, teachers, students, and scholars of dance, the elite forged friendships with tutors and performers, often becoming their students and sometimes becoming teachers themselves.

Newton Gunasinghe has observed how British officials found it expedient to patronise feudal elites, after a series of rebellions that threatened to bring down the colonial order. Yet even before this, such officials had patronised cultural practices that had once been the preserve of those elites. It was through this tenuous relationship between colonialism and cultural revival that Westernised low country elites moved away from conventional careers, like law and medicine, into the arduous task of reviving the past.

At first running into opposition from their paterfamilias, the scions of the elite eventually found their calling. “[I]n spite of their disappointment at my smashing their hopes of a brilliant legal and political career,” Charles Jacob Peiris, later to be known as Devar Surya Sena, wrote in his recollection of his parents’ reaction to a concert he had organised at the Royal College Hall in 1929, “they were proud of me that night.”

If the sons had to incur the wrath of their fathers, the daughters had to pay the bigger price. Yet, as with the sons, the daughters too possessed an agency that emboldened them to not just dance, but participate in rituals that had been restricted to males.

Both Miriam Pieris and Chandralekha Perera displeased traditional society when they donned the ves thattuwa, the sacred headdress that had for centuries been reserved for men. But for every critic, there were those who welcomed such developments, considering them essential to the flowering of the arts; none less than Martin Wickramasinghe, to give one example, viewed Chandralekha’s act positively, and commended her.

These developments sparked off a pivotal cultural renaissance across the country. Although up country women remain debarred from those developments, there is no doubt that the shattering of taboos in the low country helped keep the art of the dance alive, for tutors, students, and scholars. As Mirak Raheem has written in a piece to Groundviews, we are yet to appreciate the role female dancers of the early 20th century played in all this.

Vajira Chitrasena’s contribution went beyond that of the daughters of the colonial elite who dared to dance. While it would be wrong to consider their interest as a passing fad, a quirk, these women did not turn dance into a lifelong profession. Vajira did not just commit herself to the medium in a way they had not, she made it her goal to teach and reinterpret it, in line with methods and practices she developed for the Chitrasena Kala Ayathanaya.

As Mirak Raheem has pointed out in his tribute to her, she drew from her limited exposure to dance forms like classical ballet to design a curriculum that broke down the medium to “a series of exercises… that could be used to train dancers.” In doing so, she conceived some highly original works, including a set of children’s ballets, or lama mudra natya, a genre she pioneered in 1952 with Kumudini. Along the way she crisscrossed several roles, from dancer to choreographer to tutor, becoming more than just a performer.

As the head of the Chitrasena Dance Company, Vajira enjoys a reputation that history has not accorded to most other women of her standing. Perhaps her greatest contribution in this regard has been her ability to adapt masculine forms of dance to feminine sequences. She has been able to do this without radically altering their essence; that has arguably been felt the most in the realm of Kandyan dance, which caters to masculine (“tandava“) rather than feminine (“lasya“) moods. The lasya has been described by Marianne Nürnberger as a feminine form of up country dance. It was in productions like Nala Damayanthi that Vajira mastered this form; it epitomised a radical transformation of the art.

Sudesh Mantillake in an essay on the subject (“Masculinity in Kandyan Dance”) suggests that by treating them as impure, traditional artistes kept women away from udarata natum. That is why Algama Kiriganitha, who taught Chandralekha, taught her very little, since she was a woman. This is not to say that the gurunannses kept their knowledge back from those who came to learn from them, only that they taught them under strictures and conditions which revealed their reluctance to impart their knowledge to females.

That Vajira Chitrasena made her mark in these fields despite all obstructions is a tribute to her mettle and perseverance. Yet would we, as Mirak Raheem suggests in his very excellent essay, be doing her a disservice by just valorising her? Shouldn’t the object of a tribute be, not merely to praise her for transcending gender barriers, but more importantly to examine how she transcended them, and how difficult she found it to transcend them? We eulogise our women for breaking through the glass ceiling, without questioning how high that ceiling was in the first place. A more sober evaluation of Vajira Chitrasena would ask that question. But such an evaluation is yet to come out. One can only hope that it will, soon.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

Features

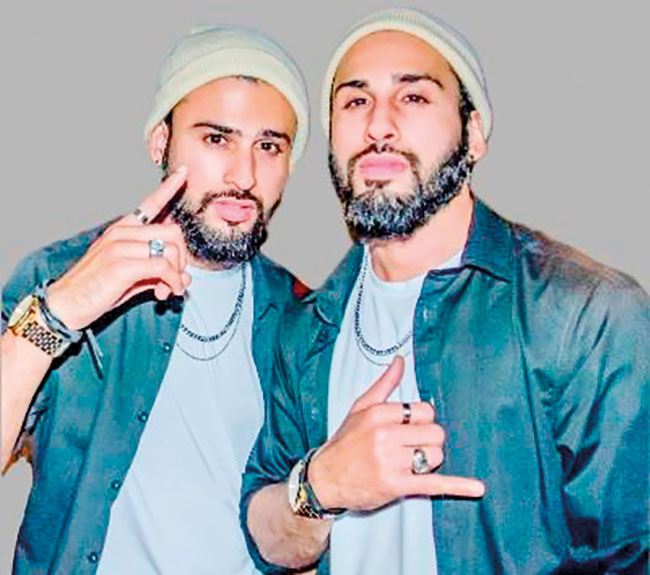

Special milestone for JJ Twins

The JJ Twins, the Sri Lankan musical duo, performing in the Maldives, and known for blending R&B, Hip Hop, and Sri Lankan rhythms, thereby creating a unique sound, have come out with a brand-new single ‘Me Mawathe.’

In fact, it’s a very special milestone for the twin brothers, Julian and Jason Prins, as ‘Me Mawathe’ is their first ever Sinhala song!

‘Me Mawathe’ showcases a fresh new sound, while staying true to the signature harmony and emotion that their fans love.

This heartfelt track captures the beauty of love, journey, and connection, brought to life through powerful vocals and captivating melodies.

It marks an exciting new chapter for the JJ Twins as they expand their musical journey and connect with audiences in a whole new way.

Their recent album, ‘CONCLUDED,’ explores themes of love, heartbreak, and healing, and include hits like ‘Can’t Get You Off My Mind’ and ‘You Left Me Here to Die’ which showcase their emotional intensity.

Readers could stay connected and follow JJ Twins on social media for exclusive updates, behind-the-scenes moments, and upcoming releases:

Instagram: http://instagram.com/jjtwinsofficial

TikTok: http://tiktok.com/@jjtwinsmusic

Facebook: http://facebook.com/jjtwinssingers

YouTube: http://youtube.com/jjtwins

Features

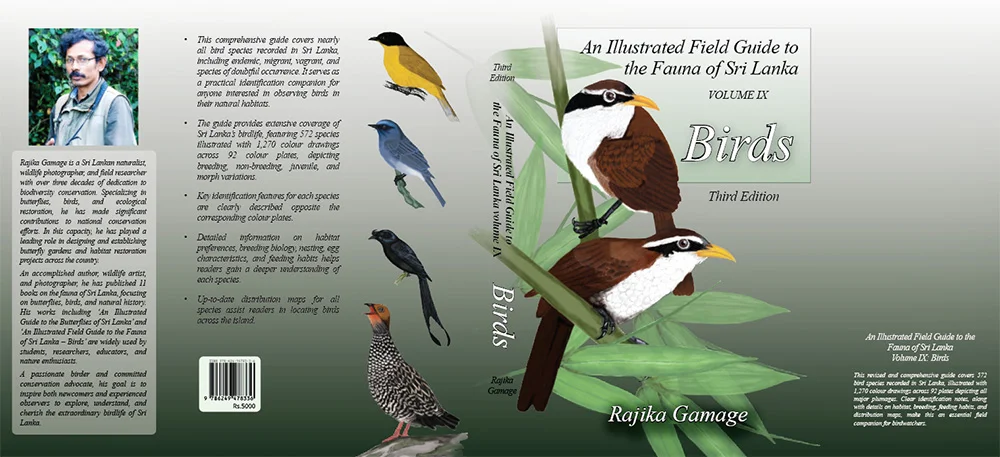

A life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

Sri Lanka wakes each morning to wings.

From the liquid whistle of a magpie robin in a garden hedge to the distant circling silhouette of an eagle above a forest canopy, birds define the rhythm of the island’s days.

Their colours ignite the imagination; their calls stir memory; their presence offers reassurance that nature still breathes alongside humanity. For conservation biologist Rajika Gamage, these winged lives are more than fleeting beauty—they are a lifelong calling.

Now, after years of patient observation, artistic collaboration, and scientific dedication, Gamage’s latest book, An Illustrated Field Guide to the Fauna of Sri Lanka – Birds, is set to reach readers when it hits the market on March 6.

The new edition promises to become one of the most comprehensive and visually rich bird guides ever produced for Sri Lanka.

Speaking to The Island, Gamage reflected on the inspiration behind his work and the enduring fascination birds hold for people across the country.

“Birds are an incredibly diverse group,” he said. “Their bright colours, distinct songs and calls, and showy displays contribute to their uniqueness, which is appreciated by all bird-loving individuals.”

Birds, he explained, occupy a special place in the natural world because they are among the most visible forms of wildlife. Unlike elusive mammals or secretive reptiles, birds share human spaces openly.

“Birds are widely distributed in all parts of the globe in large enough populations, making them the most common wildlife around human habitations,” Gamage said. “This offers a unique opportunity for observing and monitoring their diverse plumage and behaviours for conservation and recreational purposes.”

This accessibility has made birdwatching one of the most popular forms of wildlife observation in Sri Lanka, attracting everyone from seasoned scientists to curious schoolchildren.

A remarkable island of avian diversity

Despite its small size, Sri Lanka possesses extraordinary bird diversity.

According to Gamage, the country’s geographic position, varied climate, and diverse habitats—from coastal wetlands and rainforests to montane cloud forests and dry-zone scrublands—have created ideal conditions for birdlife.

“Sri Lanka is home to a rich diversity of birdlife, with a total of 522 bird species recorded in the country,” he said. “These species are spread across 23 orders, 89 families, and 267 genera.”

Of these, 478 species have been fully confirmed. Among them, 209 are breeding residents, meaning they live and reproduce on the island throughout the year.

Even more remarkable is Sri Lanka’s high level of endemism.

“Thirty-five of these breeding resident species are endemic to Sri Lanka,” Gamage noted. “They are confined entirely to the island, making them globally significant.”

These endemic species—from forest-dwelling flycatchers to vividly coloured barbets—represent evolutionary lineages shaped by Sri Lanka’s long geological isolation and ecological uniqueness.

In addition to resident birds, Sri Lanka also serves as a seasonal refuge for migratory species traveling thousands of kilometres.

“There are regular migrants that arrive annually, as well as irregular migrants that visit less predictably,” Gamage explained. “Vagrants, birds that appear outside their typical migratory routes, have also been spotted occasionally.”

Such unexpected visitors often generate excitement among birdwatchers and scientists alike, providing valuable insights into migration patterns and environmental change.

Rajika Gamage

A guide born from passion and necessity

The new field guide represents the culmination of years of research and builds upon Gamage’s earlier publication, which was released in 2017.

“The stimulus for this bird guide was due to the success of my first book,” he said. “This new edition aims to facilitate identification and provide an idea of what to look for in observed habitats or regions.”

The book is designed not merely as a scientific reference but as an accessible companion for anyone interested in birds. Its structure reflects this dual purpose.

“The first section is dedicated to the introduction, geography, and life history of Sri Lankan birds,” Gamage explained. “The second section is the main body of the guide, which illustrates 532 species of birds.”

Each illustration has been carefully crafted in colour to capture the distinctive plumage of each species.

“All illustrations are designed to show each bird’s significant and distinct plumage,” he said. “Where possible, the breeding, non-breeding, and juvenile plumages are provided.”

This attention to detail is especially important because many birds change appearance as they mature.

“Some groups, especially gulls, display many plumages between juveniles and adults,” Gamage noted. “Many take several years to develop full adult plumage and pass through semi-adult stages.”

By illustrating these stages, the guide helps birdwatchers avoid misidentification and deepen their understanding of avian development.

New discoveries and evolving science

One of the most exciting aspects of the new edition is its inclusion of newly recorded species and updated scientific classifications.

“Changes in the bird list of Sri Lanka, especially newly added endemic birds such as the Sri Lankan Shama, Sri Lanka Lesser Flameback, and Greater Flameback, are now included,” Gamage said.

Scientific names and classifications are not static; they evolve as researchers learn more about genetic relationships and species boundaries. The guide reflects these changes, ensuring it remains scientifically current.

The book also incorporates conservation status information based on the latest National Red Data Report and global assessments.

“The conservation status of Sri Lankan birds, as listed in the 2022 National Red Data Report and the global Red Data Report, are included,” Gamage said.

This information is vital for conservation planning and public awareness, highlighting which species face the greatest risk of extinction.

The guide also documents rare and accidental visitors, including species such as the Blue-and-white Flycatcher, Rufous-tailed Rock-thrush, and European Honey-buzzard.

“These represent accidental visitors and newly recorded vagrants,” Gamage said. “Altogether, the first edition offers some 25 additional species, all illustrated.”

Art and science in harmony

Unlike many field guides that rely heavily on photographs, Gamage’s book emphasises detailed illustrations. This choice reflects the unique advantages of scientific art.

Illustrations can emphasise diagnostic features, eliminate distracting backgrounds, and present birds in standardised poses, making identification easier.

“The principal birds on each page are painted to a standard scale,” Gamage explained. “Flight and behavioural sketches are shown at smaller scales.”

The guide also includes descriptions of habitats, distribution, nesting behaviour, and alternative names in English, Sinhala, and Tamil.

“The majority of birds have more than one English, Sinhala, and Tamil name,” he said. “All of these are included.”

This multilingual approach reflects Sri Lanka’s cultural diversity and ensures the guide is accessible to a wider audience.

A tool for conservation and connection

Beyond its scientific value, Gamage believes the book serves a deeper purpose: strengthening the bond between people and nature.

By helping readers identify birds and understand their lives, the guide fosters appreciation and responsibility.

“This field guide aims to facilitate identification and provide a general introduction to birds,” he said.

In an era of rapid environmental change, such knowledge is essential. Habitat loss, climate change, and human activity continue to threaten bird populations worldwide, including in Sri Lanka.

Yet birds also offer hope.

Their presence in gardens, wetlands, and forests reminds people of nature’s resilience—and their own role in protecting it.

Gamage hopes the guide will inspire both seasoned ornithologists and beginners alike.

“All these changes will make An Illustrated Field Guide to the Fauna of Sri Lanka – Birds one of the most comprehensive and accurate guides available within Sri Lanka,” he said.

A lifelong devotion takes flight

For Rajika Gamage, birds are not merely subjects of study—they are companions in a lifelong journey of discovery.

Each call heard at dawn, each silhouette glimpsed against the sky, each feathered visitor from distant lands reinforces the wonder that first drew him to ornithology.

With the release of his new book on March 6, that wonder will now be shared more widely than ever before.

In its pages, readers will find not only identification keys and scientific facts, but also something more enduring—the story of an island, told through wings, colour, and song.

By Ifham Nizam

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features6 days ago

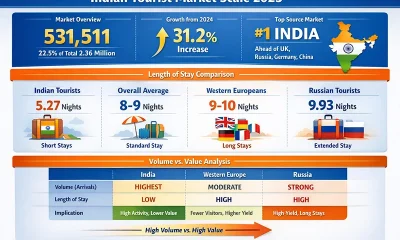

Features6 days agoBuilding on Sand: The Indian market trap

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoFuture must be won

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog partners with Xiaomi to introduce Redmi Note 15 5G Series in Sri Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoCEA halts development at Mandativu grounds until EIA completion