Features

“TRAVEL SAFE – TRAVEL CHEAP – TRAVEL BY RAIL.”

By Rohan Abeygunawardena

ACMA, CGMA: Financial and Management Consultant.

abeyrohan@gmail.com

(This article is dedicated to all those officers and other employees who worked under the late Mr. Rampala, during “Golden Era “of the CGR from the late 1940s’ to 1970 including my father the late Mr. G.A.V. Abeygunawardena)

Above was a marketing campaign slogan based on a concept of the legendary leader of Ceylon Government Railway (CGR) B.D. Rampala to attract passengers for train travel.

Rampala was the first Ceylonese Chief Mechanical Engineer from 1949 and then was appointed to the newly created post of General Manager of Railway (GMR) in 1955. He joined CGR in 1934 as a Junior Mechanical Engineer after completing his engineering apprenticeship at the Colombo University College. In 1956, the Institution of Locomotive Engineers in London recognised him as the finest diesel engineer in Asia at the time (Wikipedia.)

History of Sri Lanka Railway

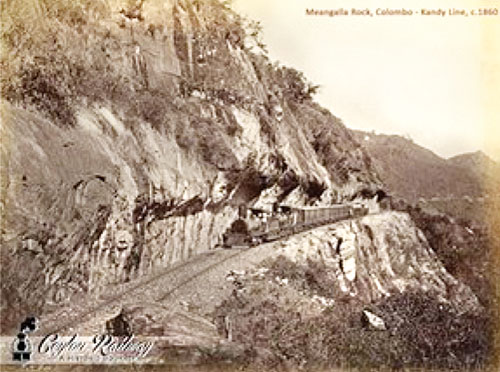

It was the coffee planters who first felt the need to construct a railroad system in Sri Lanka (then Ceylon) in 1842. Under pressure from this elite group of the crown colony, Ceylon Railway Company (CRC) was established in 1845 under the Chairmanship of Phillip Anstruther, the Chief Secretary of Ceylon. The contractor William Thomas Doyne was selected for constructing the 79-mile (123 km) Colombo Kandy railway line and later it was realised that the project could not be completed within the original estimate of £856,557. In 1861, Ceylon Government Railway (CGR) was established as a department and took over the construction work. Guilford Lindsey Molesworth, an experienced railway engineer from London, was appointed as the Director General of the CGR.

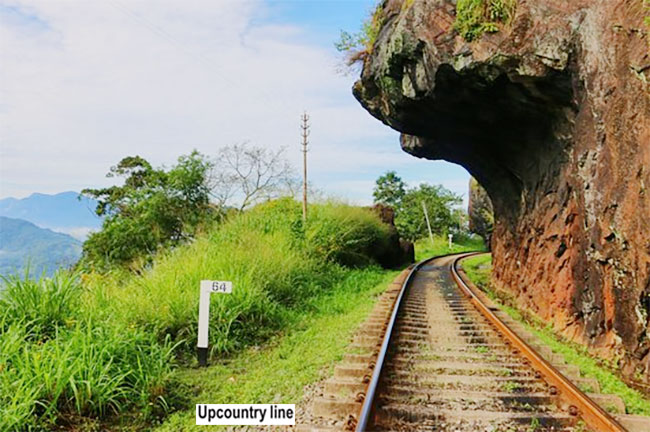

It took nearly 22 years to build the first stretch of railroad and run the first train from Colombo to Ambepussa in December 1864. It was then extended to Kandy in 1867, the main request of British Planters. Thereafter to Nawalapitiya, Nanuoya, Bandarawella, and Badulla by 1924. However by 1928, the Matale line, the Kankasanturai (Northern Line), the Southern Coast Line, the Mannar Line, the Kelani Valley Line, the Puttalam Line, the Batticaloa and Trincomalee lines were added to the network.

Golden Era of Sri Lanka Railway

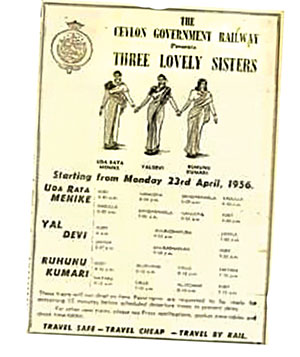

Visionary Rampala had a helicopter view of the organisation. During his tenure as the GMR many modernisation programmes were introduced. He had systematically planned to replace British-built steam locomotives with Diesel locomotives over a 20-year period. Five G12 Diesel locomotives, gifted by the Canadian Government, in 1954, were utilised to run Sri Lanka’s most famous trains, the Udarata Menike, the Yal Devi, and the Ruhunu Kumari, the three sisters on rails.

Visionary Rampala had a helicopter view of the organisation. During his tenure as the GMR many modernisation programmes were introduced. He had systematically planned to replace British-built steam locomotives with Diesel locomotives over a 20-year period. Five G12 Diesel locomotives, gifted by the Canadian Government, in 1954, were utilised to run Sri Lanka’s most famous trains, the Udarata Menike, the Yal Devi, and the Ruhunu Kumari, the three sisters on rails.

Emphasising punctuality and comfort, major stations outside Colombo were upgraded during the Rampala era. He also introduced an electronic signal system controlled by a centralised traffic control panel in Maradana, which greatly improved safety. In order to popularise rail travel he carried out a marketing exercise of the railway service through a slogan “Travel Safe – Travel Cheap – Travel by Rail.” The objective of this marketing campaign was to attract non-traditional rail passengers, such as women and children, and increase the market share of travellers and improve income of CGR.

Rampala tenure is considered as the ‘Golden Era of Sri Lanka Railways.’ He successfully conducted the grand Centenary Celebrations held in 1964. The main highlight was a refurbished old steam engine driven train, with old carriages, operating from the Colombo Terminus station of Olcott Mawatha to Ambepussa, carrying passengers, driver and guard dressed in late 19th century attire. The train left around 8 a.m. followed by a diesel engine, driven modern train carrying CGR employees and their immediate family members. The writer who was just 14 years was lucky enough to travel in that train with his father who was an officer in the CGR. An exhibition of model trains was also held at Maradana head office for the public. Some of the models were locally made by railroad enthusiasts and CGR engineers while others were imported models owned by locals and foreigners.

In spite of an economic decline in the country Sri Lanka Railways (SLR) continued with the numbers of its passenger services and enjoyed nearly 38% of freight transportation in the early seventies.

But with the introduction of the open economy, the road transportation systems improved and private road transport services that provided door-to-door or warehouse-to-warehouse service captured a bigger chunk of the freight service market of the country. The three-decades-long civil war, non-introduction of technological innovations that improved railway travel worldwide, issues of travel time, reliability, and comfort plagued Sri Lanka Railways said the Chief Engineer (Signal and Telecomunications) Dhammika Jayasundara who delivered the B.D. Rampala memorial lecture in 2017.

US the world leader of railway

transportation:

The US had the best railway transportation system in the world, prior to World War II, with an operating route length over 250,000 km. But after the war, the American auto industry owners came out with a new concept ‘’Freedom on Wheels’’ to get people to use cars. This concept was to promote motor car industry and propagated by the companies in the auto and oil industries to enhance their profits. Initially, they bought up all the street cars i. e. trolleybuses and Tramcars relegating them to junkyards, and embarked on increasing the motor car production.

The government under President Eisenhower, signed a Bill to create the “The National Interstate System’’ and allocated funds for the construction of 41,000 miles of highways and the US shifted from a rail served country to auto dependent nation by the mid-sixties. They dedicated a huge amount of dollars to the construction of automobile infrastructure.

By 2019, the US averaged about 850 cars per one thousand inhabitants. Many countries in the west and Asia emulated the US and constructed highways. Indians, on the other hand continued to improve the railroad transportation system over the years. The Average Sri Lankan was dreaming of owning a car and when the economy was opened up in the late seventies, an influx of motorcars, motorcycles and other vehicles, both brand new and used, invaded the country.

Similarly, the expansion of air travel took place since the fifties, not only in the US but also in other countries. In the US internal air service systems were expanded rapidly for travel between cities.

In Sri Lanka too the government embarked on a project to improve road transport. During the Civil War it was on a low profile but increased construction of highways or express ways after the war from 2009.

Recent developments;

An efficient transport system is an indispensable component of a modern country, no doubt. They provide economic and social opportunities and benefits that result in positive multiplier effects such as better accessibility to markets, employment, and additional investments. Recently, this writer was approached by a group of industrialists to draw up a concept note to obtain land and other facilities from the authorities to set up new factories. One important requirement they emphasised was that location of the land should be close to an expressway. Since they have been into exports this is a fair request as their finished products should be moved to ports and airports as quickly as possible for shipping.

With the development of highways, especially expressways, Sri Lanka Railways (SLR), the market share of passenger and goods transportation has considerably dropped. Chief Engineer Dhammika Jayasundara in his 2017 lecture stated that while SLR’s share of passenger transportation market was only about 5% and goods transportation market share was around 0.3%. It would definitely have deteriorated further by now.

An opportunity for SLR:

The US is reassessing its transport systems at present. They have realised that the country is running out of space to expand the highways. There are limits at airports and aviation congestion is also an acute problem. Looking out for a solution, the US has now realised a better railway system is the best option.

The US is reassessing its transport systems at present. They have realised that the country is running out of space to expand the highways. There are limits at airports and aviation congestion is also an acute problem. Looking out for a solution, the US has now realised a better railway system is the best option.

But in today’s global economy ‘’time-saving methods” and “reduction of greenhouse gases” are two important factors when considering development projects. Therefore, electrified high-speed train is the best option to switch from air traffic and vehicles. A survey conducted indicates 71% of the younger generation (18 to 44) in the US prefer travelling by high-speed trains if available. Train systems reaching top speed of over 175 to 240 km per hour is generally considered high-speed. A plan is now in place to build a 27,000 km national high-speed rail system in four phases by 2030. The first project is to connect San Francisco to Los Angeles (about 613km) in less than three hours at a speed of about 350km/h by 2033.

When a high-speed train was introduced between Madrid–Barcelona in Spain in 2008, it took 46% of the traffic, grounding fuel-guzzling, carbon-emitting aircrafts across Spain. This high-speed train pulled by an aerodynamic engine with noses shaped like a duck-billed platypus covers 621km trip in two and half hours at a maximum speed of 350 km/h. The train has the capacity to carry 430 passengers per trip and operates four trips a day. This is an eye-opener to the Americans as well as transport authorities of other countries.

The first high-speed train the Tōkaidō Shinkansen, began operations in Japan in 1964 and was widely known as the ‘bullet train’. France commenced their first high-speed train in 1981 and as of June 2021 had a network 2,800 km.

In many developed countries, faced with issues such as aging population, rising fuel prices, increasing urbanization, increasing traffic congestion, rising roadway expansion costs, changing consumer preferences and increasing health and environmental concerns are shifting travel demand from automobile to alternative modes. Motor vehicles are the greatest contributor to urban air pollution, leading to health problems, worse than smoking and the other factor is deaths through road accidents.

Likely alternative is the high-speed train. This is the most cost-effective transportation mode for moving large numbers of people and compared to road and air transportation less risky as far as accidents are concerned. Today, high-speed train systems are being introduced all over the world in countries like India, Saudi Arabia, Russia, Iran and Morocco. China is the world leader in the construction of high-speed railway systems. By the end of 2020, the Chinese had 37,900 km of high-speed rail lines in service, the longest in the world.

Long-term- plan for SLR

Sri Lanka Railways should study the changing nature of transportation system in developed countries. Since our island nation does not have to cover distances like in the countries mentioned above, railway authorities benchmark a country like Denmark with an area of 42,933 sq. km and a population of 5.8 million. The first ever high-speed train on Copenhagen–Ringsted line commenced on the 31st May 2019 covering 60 km. It has a maximum speed of 250 km/h and covers the trip within 35 minutes. The project received approval from the Danish Parliament in 2010 and was completed in 2019 at a cost of US$ 1.83 billion.

Sri Lanka Railways should study the changing nature of transportation system in developed countries. Since our island nation does not have to cover distances like in the countries mentioned above, railway authorities benchmark a country like Denmark with an area of 42,933 sq. km and a population of 5.8 million. The first ever high-speed train on Copenhagen–Ringsted line commenced on the 31st May 2019 covering 60 km. It has a maximum speed of 250 km/h and covers the trip within 35 minutes. The project received approval from the Danish Parliament in 2010 and was completed in 2019 at a cost of US$ 1.83 billion.

In Sri Lanka, the fastest train service is between Colombo and Beliatta covering 158 km with a maximum speed of 120 km/h. The fastest train ‘Galu Kumari’ takes three and a half hours to cover this distance.

Future generation of sophisticated and knowledgeable Sri Lankans are bound to switch over to train travel and will demand much faster mobility between cities. For example,

if Colombo Jaffna (304 km) travelling can be completed within two hours, instead of present eight hours, there will be lot of economic and social benefits to the country including communal harmony through better interaction. Such speedy travel can only be achieved by rail road or costly air travel, not by motor road vehicles.

However, the capital cost of introducing a High-Speed Railway (HSR) project is very high. The cost structure is mainly divided into costs associated to the infrastructure, and the ones associated with the rolling stock. While infrastructure costs include investments in construction and maintenance of the railroad, the cost of acquisition, operation and maintenance of rolling stock is determined by its technical specifications. SLR engineers and other experts should work out specification suitable for Sri Lanka.

It is necessary for SLR official to take into account the impact on wildlife when planning high-speed train track which British planners had not taken into account during colonial period. As a result, many elephants collide with fast moving trains and perish. According to the Department of Wildlife figures, 15 elephants were killed by trains in 2018, almost more than double the previous year (Mark Saunokonoko – 07 Jan., 2019.) It may be possible for trains to run on cement pillars where the elephant corridors are located.

Taking into consideration the distance from Colombo to Beliatta (158km), Jaffna (304 km) and Kandy (120km) SLR should plan for a total distance of 582 km of high-speed train service. A ballpark figure extrapolated on the basis of Copenhagen–Ringsted line construction, the total cost would be approximately US$ 18 billion. If planned for 20 years this is an average investment of about US$ 900 million per year. The government could approach funding agencies such as the World Bank (WB), the Asian Development Bank (ADB),, and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) funding of the project and to carry out a feasibility study.

The implementation of this project depends on the development of the energy sector. Best option is the development of solar power which can provide free electricity to all, according to renowned Sri Lankan scientist, Prof. Ravi Silva, Director, Advanced Technology Institute at the University of Surrey, who was awarded a CBE for his services to Science, Education and Research. (Reference below)

President Gotabaya Rajapaksa is also keen to attract large scale investments in renewable energy, particularly in solar, wind and biomass, over the coming decades.

One may ask whether a country facing economic problems and borrowing crisis should embark on a project of this nature. The answer is in the affirmative. As Asia is expected to rebound faster compared to other regions after the global recession and the pandemic, Sri Lanka has an opportunity to attract investment in the long term. But such investment should be futuristic and in projects that have a greater payoff in the future. The ‘Mahawali Project’ was to be completed in 35 years, but it was telescoped into five years. Similarly, the speed-train project should be a national policy long-term plan, and depending on the economy can be accelerated.

The development of high-speed train does not mean that the government and the Road Development Authority should abandon the development plan of the High Mobility Network or construction of Expressways. It is necessary at present for better connectivity. But a futuristic plan for Sri Lanka Railways should be based on changes taking place, world over.

The implementation of such a modernisation project will help realise the vision of the late B.D. Rampala ‘Travel Safe – Travel Cheap – Travel by Rail’. It will also justify the need to continue with the railway services without heavy subsidies and be a burden on taxpayers’ money.

References;

(Let the Sun Shine: Do not let a photon go to waste without benefit to mankind https://www.timesonline.lk/opinion/let-the-sun-shine-do-not-let-a-photon-go-to-waste-without-benefit-to-mankind/158-1120004 .)

Features

Humanitarian leadership in a time of war

There has been a rare consensus of opinion in the country that the government’s humanitarian response to the sinking of Iran’s naval ship IRIS Dena was the correct one. The support has spanned the party political spectrum and different sections of society. Social media commentary, statements by political parties and discussion in mainstream media have all largely taken the position that Sri Lanka acted in accordance with humanitarian principles and international law. In a period when public debate in Sri Lanka is often sharply divided, the sense of agreement on this issue is noteworthy and reflects positively on the ethos and culture of a society that cares for those in distress. A similar phenomenon was to be witnessed in the rallying of people of all ethnicities and backgrounds to help those affected by the Ditwah Cyclone in December last year.

The events that led to this situation unfolded with dramatic speed. In the early hours before sunrise the Dina made a distress call. The ship was one of three Iranian naval vessels that had taken part in a naval gathering organised by India in which more than 70 countries had participated, including Sri Lanka. Naval gatherings of this nature are intended to foster professional exchange, confidence building and goodwill between navies. They are also governed by strict protocols regarding armaments and conduct.

When the exhibition ended open war between the United States and Iran had not yet broken out. The three Iranian ships that participated in the exhibition left the Indian port and headed into international waters on their journey back home. Under the protocol governing such gatherings ships may not be equipped with offensive armaments. This left them particularly vulnerable once the regional situation changed dramatically, though the US Indo-Pacific Command insists the ship was armed. The sudden outbreak of war between the United States and Iran would have alerted the Iranian ships that they were sailing into danger. According to reports, they sought safe harbour and requested docking in Sri Lanka’s ports but before the Sri Lankan government could respond the Dena was fatally hit by a torpedo.

International Law

The sinking of the Dena occurred just outside Sri Lanka’s territorial waters. Whatever decision the Sri Lankan government made at this time was bound to be fraught with consequence. The war that is currently being fought in the Middle East is a no-holds-barred one in which more than 15 countries have come under attack. Now the sinking of the Dena so close to Sri Lanka’s maritime boundary has meant that the war has come to the very shores of the country. In times of war emotions run high on all sides and perceptions of friend and enemy can easily become distorted. Parties involved in the conflict tend to gravitate to the position that “those who are not with us are against us.” Such a mindset leaves little room for neutrality or humanitarian discretion.

In such situations countries that are not directly involved in the conflict may wish to remain outside it by avoiding engagement. Foreign Minister Vijitha Herath informed the international media that Sri Lanka’s response to the present crisis was rooted in humanitarian principles, international law and the United Nations. The Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which was adopted 1982 provides the legal framework governing maritime conduct and obliges states to render assistance to persons in distress at sea. In terms of UNCLOS, countries are required to render help to anyone facing danger in maritime waters regardless of nationality or the circumstances that led to the emergency. Sri Lanka’s response to the distress call therefore reflects both humanitarianism and adherence to international law.

Within a short period of receiving the distress message from the stricken Iranian warship the Sri Lankan government sent its navy to the rescue. They rescued more than thirty Iranian sailors who had survived the attack and were struggling in the water. The rescue operation also brought to Sri Lanka the bodies of those who had perished when their ship sank. The scale of the humanitarian challenge is significant. Sri Lanka now has custody of more than eighty bodies of sailors who lost their lives in the sinking of the Dena. In addition, a second Iranian naval ship IRINS Bushehr with more than two hundred sailors has come under Sri Lanka’s protection. The government therefore finds itself responsible for survivors but also for the dignified treatment of the bodies of the dead Iranian sailors.

Sri Lanka’s decision to render aid based on humanitarian principles, not political allegiance, reinforces the importance of a rules-based international order for all countries. Reliance on international law is particularly important for small countries like Sri Lanka that lack the power to defend themselves against larger actors. For such countries a rules-based international order provides at least a measure of protection by ensuring that all states operate within a framework of agreed norms. Sri Lanka itself has played a notable role in promoting such norms. In 1971 the United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution declaring the Indian Ocean a Zone of Peace. The initiative for this proposal came from Sri Lanka, which argued that the Indian Ocean should be protected from great power rivalry and militarisation.

Moral Beacon

Unfortunately, the current global climate suggests that the rules-based order is barely operative. Conflicts in different parts of the world have increasingly shown disregard for the norms and institutions that were created in the aftermath of the Second World War to regulate international behaviour. In such circumstances it becomes even more important for smaller countries to demonstrate their commitment to international law and to convert the bigger countries to adopt more humane and universal thinking. The humanitarian response to the Iranian sailors therefore needs to be seen in this wider context. By acting swiftly to rescue those in distress and by affirming that its actions are guided by international law, Sri Lanka has enhanced its reputation as a small country that values peace, humane values, cooperation and the rule of law. It would be a relief to the Sri Lankan government that earlier communications that the US government was urging Sri Lanka not to repatriate the Iranian sailors has been modified to the US publicly acknowledging the applicability of international law to what Sri Lanka does.

The country’s own experience of internal conflict has shaped public consciousness in important ways. Sri Lanka endured a violent internal war that lasted nearly three decades. During that period questions relating to the treatment of combatants, the protection of civilians, missing persons and accountability became central issues. As a result, Sri Lankans today are familiar with the provisions of international law that deal with war crimes, the treatment of wounded or disabled combatants and the fate of those who go missing in conflict. The country continues to host an international presence in the form of UN agencies and the ICRC that work with the government on humanitarian and post conflict issues. The government needs to apply the same principled commitment of humanitarianism and the rule of law to the unresolved issues from Sri Lanka’s own civil war, including accountability and reconciliation.

By affirming humanitarian principles and acting accordingly towards the Iranian sailors and their ship Sri Lanka has become a moral beacon for peace and goodwill in a world that often appears to be moving in the opposite direction. At a time when geopolitical rivalries are intensifying and humanitarian norms are frequently ignored, such actions carry symbolic significance. The credibility of Sri Lanka’s moral stance abroad will be further enhanced by its ability to uphold similar principles at home. Sri Lanka continues to grapple with unresolved issues arising from its own internal conflict including questions of accountability, justice, reparations and reconciliation. It has a duty not only to its own citizens, but also to suffering humanity everywhere. Addressing its own internal issues sincerely will strengthen Sri Lanka’s moral standing in the international community and help it to be a force for a new and better world.

BY Jehan Perera

Features

Language: The symbolic expression of thought

It was Henry Sweet, the English phonetician and language scholar, who said, “Language may be defined as the expression of thought by means of speech sounds“. In today’s context, where language extends beyond spoken sounds to written text, and even into signs, it is best to generalise more and express that language is the “symbolic expression of thought“. The opposite is also true: without the ability to think, there will not be a proper development of the ability to express in a language, as seen in individuals with intellectual disability.

Viewing language as the symbolic expression of thought is a philosophical way to look at early childhood education. It suggests that language is not just about learning words; it is about a child learning that one thing, be it a sound, a scribble, or a gesture, can represent something else, such as an object, a feeling, or an idea. It facilitates the ever-so-important understanding of the given occurrence rather than committing it purely to memory. In the world of a 0–5-year-old, this “symbolic leap” of understanding is the single most important cognitive milestone.

Of course, learning a language or even more than one language is absolutely crucial for education. Here is how that viewpoint fits into early life education:

1. From Concrete to Abstract

Infants live in a “concrete” world: if they cannot see it or touch it, it does not exist. Early education helps them to move toward symbolic thought. When a toddler realises that the sound “ball” stands for that round, bouncy thing in the corner, they have decoded a symbol. Teachers and parents need to facilitate this by connecting physical objects to labels constantly. This is why “Show and Tell” is a staple of early education, as it gently compels the child to use symbols, words or actions to describe a tangible object to others, who might not even see it clearly.

2. The Multi-Modal Nature of Symbols

Because language is “symbolic,” it does not matter how exactly it is expressed. The human brain treats spoken words, written text, and sign language with similar neural machinery.

Many educators advocate the use of “Baby Signs” (simple gestures) before a child can speak. This is powerful because it proves the child has the thought (e.g., “I am hungry”) and can use a symbol like putting the hand to the mouth, before their vocal cords are physically ready to produce the word denoting hunger.

Writing is the most abstract symbol of all: it is a squiggle written on a page, representing a sound, which represents an idea or a thought. Early childhood education prepares children for this by encouraging “emergent writing” (scribbling), even where a child proudly points to a messy circle that the child has drawn and says, “This says ‘I love Mommy’.”

3. Symbolic Play (The Dress Rehearsal)

As recognised in many quarters, play is where this theory comes to life. Between ages 2 and 3, children enter the Symbolic Play stage. Often, there is object substitution, as when a child picks up a banana and holds it to his or her ear like a telephone. In effect, this is a massive intellectual achievement. The child is mentally “decoupling” the object from its physical reality and assigning it a symbolic meaning. In early education, we need to encourage this because if a child can use a block as a “car,” they are developing the mental flexibility required to later understand that the letter “C” stands for the sound of “K” as well.

4. Language as a Tool for “Internal Thought”

Perhaps the most fascinating fit is the work of psychologist Lev Vygotsky, who argued that language eventually turns inward to become private speech. Have you ever seen a 4-year-old talking to himself or herself while building a toy tower? “No, the big one goes here….. the red one goes here…. steady… there.” That is a form of self-regulation. Educators encourage this “thinking out loudly.” It is the way children use the symbol system of language to organise their own thoughts and solve problems. Eventually, this speech becomes silent as “inner thought.”

Finally, there is the charming thought of the feasibility of conversing with very young children in two or even three or more languages. In Sri Lanka, the three main languages are Sinhala, Tamil and English. There are questions asked as to whether it is OK to talk to little ones in all three languages or even in two, so that they would learn?

According to scientific authorities, the short, clear and unequivocal answer to that query is that not only is it “OK”, it is also a significant cognitive gift to a child.

In a trilingual environment like Sri Lanka, many parents worry that multiple languages will “confuse” a child or cause a “speech delay.” However, modern neuroscience has debunked these myths. The infant brain is perfectly capable of building three or even more separate “lexicons” (vocabularies) simultaneously.

Here is how the “symbolic expression of thought” works in a multilingual brain and how we can manage it effectively.

a). The “Multiple Labels” Phenomenon

In a monolingual home, a child learns one symbol for an object. For example, take the word “Apple.” In a Sri Lankan trilingual home, the child learns three symbols for that same thought:

* Apple (English)

* Apal

(Sinhala – ඇපල්)

* Appil

(Tamil – ஆப்பிள்)

Because the trilingual child learns that one “thought” can be expressed by multiple “symbols,” the child’s brain becomes more flexible. This is why bilingual and trilingual children often score higher on tasks involving “executive function”, meaning the ability to switch focus and solve complex problems.

b). Is there a “Delay”?

(The Common Myth)

One might notice that a child in a trilingual home may start to speak slightly later than a monolingual peer, or they might have a smaller vocabulary in each language at age two.

However, if one adds up the total number of words they know across all three languages, they are usually ahead of monolingual children. By age five, they typically catch up in all languages and possess a much more “plastic” and adaptable brain.

c). Strategies for Success: How to Do It?

To help the child’s brain organise these three symbol systems, it helps to have some “consistency.” Here are the two most effective methods:

* One Person, One Language (OPOL), the so-called “gold standard” for multilingual families.

Amma

speaks only Sinhala, while the Father speaks only English, and the Grandparents or Nanny speak only Tamil. The child learns to associate a specific language with a specific person. Their brain creates a “map”: “When I talk to Amma, I use these sounds; when I talk to Thaththa, I use those,” etc.

*

Situational/Contextual Learning. If the parents speak all three, one could divide languages by “environment”: English at the dinner table, Sinhala during play and bath time and Tamil when visiting relatives or at the market.

These, of course, need NOT be very rigid rules, but general guidance, applied judiciously and ever-so-kindly.

d). “Code-Mixing” is Normal

We need not be alarmed if a 3-year-old says something like: “Ammi, I want that palam (fruit).” This is called Code-Mixing. It is NOT a sign of confusion; it is a sign of efficiency. The child’s brain is searching for the quickest way to express a thought and grabs the most “available” word from their three language cupboards. As they get older, perhaps around age 4 or 5, they will naturally learn to separate them perfectly.

e). The “Sri Lankan Advantage”

Growing up trilingual in Sri Lanka provides a massive social and cognitive advantage.

For a start, there will be Cultural Empathy. Language actually carries culture. A child who speaks Sinhala, Tamil, and English can navigate all social spheres of the country quite effortlessly.

In addition, there are the benefits of a Phonetic Range. Sinhala and Tamil have many sounds that do not exist in English (and even vice versa). Learning these as a child wires the ears to hear and reproduce almost any human sound, making it much easier to learn more languages (like French or Japanese) later in life.

As an abiding thought, it is the considered opinion of the author that a trilingual Sri Lanka will go a long way towards the goals and display of racial harmony, respect for different ethnic groups, and unrivalled national coordination in our beautiful Motherland. Then it would become a utopian heaven, where all people, as just Sri Lankans, can live in admirable concordant synchrony, rather than as splintered clusters divided by ethnicity, language and culture.

A Helpful Summary Checklist for Parents

* Do Not Drop a Language:

If you stop speaking Tamil because you are worried about English, the child loses that “neural real estate.” Keep all three languages going.

* High-Quality Input:

Do not just use “commands” (Eat! Sleep!). Use the Parentese and Serve and Return methods (mentioned in an earlier article) in all the languages.

* Employ Patience:

If the little one mixes up some words, just model the right words and gently correct the sentence and present it to the child like a suggestion, without scolding or finding fault with him or her. The child will then learn effortlessly and without resentment or shame.

by Dr b. J. C. Perera

by Dr b. J. C. Perera

MBBS(Cey), DCH(Cey), DCH(Eng), MD(Paediatrics), MRCP(UK), FRCP(Edin), FRCP(Lond), FRCPCH(UK), FSLCPaed, FCCP, Hony.

FRCPCH(UK), Hony. FCGP(SL)

Specialist Consultant Paediatrician and Honorary Senior Fellow, Postgraduate Institute of Medicine, University of Colombo, Sri Lanka

Features

SIMPSON’S … set to carve a distinct sonic identity

It is, indeed, encouraging to see our local artistes working on new formats, where their music is concerned.

It is, indeed, encouraging to see our local artistes working on new formats, where their music is concerned.

Variety is the spice of life, they say, and I do agree, especially when it comes to music.

Blending modern synth textures, ambient layers and soulful undertones, the group SIMPSON’S is set to carve a distinct sonic identity within Sri Lanka’s contemporary music landscape.

Their vision, they say, is not simply to produce songs, but to create emotional atmospheres – experiences that elevate, energise and resonate, both locally and beyond.

This four-piece outfit came into the scene, less than two years ago, and they are already making waves with their debut single ‘Balaporottuwak’ (Hope).

The song, I’m told, marks the beginning of a new sound, and at the forefront of ‘Balaporottuwak’ is the group’s lead vocalist and guitarist, Ryo Hera, who brings a rich cultural heritage to the stage.

As a professional Kandyan Wes dancer, Ryo’s commanding presence and textured vocals bring a distinct energy to the band’s sound.

‘Balaporottuwak’

Ryo Hera: Vocals for ‘Balaporottuwak’

is more than just a debut single – it’s a declaration of intent. The band is merging tradition and modernity, power and subtlety, to create a sound that’s both authentic and innovative.

With this song, SIMPSON’S is inviting listeners to join them on an evolving musical journey, one that’s built on vision and creativity.

The recording process for ‘Balaporottuwak’ was organic and instinctive, with the band shaping the song through live studio sessions.

Dileepa Liyanage, the keyboardist and composer, is the principal sound mind behind SIMPSON’S.

With experience spanning background scores, commercial projects, cinematic themes and jingles across multiple genres, Dileepa brings structural finesse and atmospheric depth to the band’s arrangements.

He described the recording process of ‘Balaporottuwak’ as organic and instinctive: “When Ryo Hera opens his voice, it becomes effortless to shape it into any musical colour. The tone naturally adapts.”

The band’s lineup includes Buddhima Chalanu on bass, and Savidya Yasaru on drums, and, together, they create a sound that’s not just a reflection of their individual talents, but a collective vision.

Dileepa Liyanage: Brings

structural finesse and

atmospheric depth to the

band’s arrangements

What sets SIMPSON’S apart is their decision to keep the production in-house – mixing and mastering the song themselves. This allows them to maintain their unique sound and artistic autonomy.

“We work as a family and each member is given the freedom to work out his music on the instruments he handles and then, in the studio, we put everything together,” said Dileepa, adding that their goal is to release an album, made up of Sinhala and English songs.

Steering this creative core is manager Mangala Samarajeewa, whose early career included managing various international artistes. His guidance has positioned SIMPSON’S not merely as a performing unit, but as a carefully envisioned project – one aimed at expanding Sri Lanka’s contemporary music vocabulary.

SIMPSON’S are quite active in the scene here, performing, on a regular basis, at popular venues in Colombo, and down south, as well.

They are also seen, and heard, on Spotify, TikTok, Apple Music, iTunes, and Deezer.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoUniversity of Wolverhampton confirms Ranil was officially invited

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoLegal experts decry move to demolish STC dining hall

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoFemale lawyer given 12 years RI for preparing forged deeds for Borella land

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLibrary crisis hits Pera university

-

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoDialog partners with Ratmalana Audiology Centre for World Hearing Day 2026