Features

The Tamil presence in Sinhala cinema

(Excerpted from Shared Encounters in Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand – International Centre for Ethnic Studies 2024)

by Hasini Haputhanthri

An oft-quoted saying of S.W.R.D. Bandaranaike, former premier of Ceylon who came to power in 1956 upon a wave of nationalism goes: “I have never found anything to excite the people in quite the way this language issue does”. The implication was that language was a deeply divisive issue in Ceylon. However, when it came to cinema, at least in the early years, “this language issue” was not a barrier for collaboration.

In the 1930s and the early 40s, before the advent of Sinhala talkies, Tamil films were well liked and received by Sinhala audiences. For example, the South Indian blockbuster, Chintamani (1937) was an instant hit in Ceylon. Colombo-based film critic, Lucian Rajakarunanayake reminisces in the Daily News (1 June 2010):

“The Bioscope, as films were known at the time, was screened in Plaza Cinema Wellawatta. I recall waiting in the long queue with my aunts to whom an evening of watching the bioscope was a very special occasion…Chintamani ran nearly for six months or more in Colombo and it was house full all the while. Businessmen were cashing in on the runaway popularity with the Chintamani name being used for match-boxes, candles and joss-sticks. Many children were given the name too, by parents who must have seen the film several times and were singing and humming the songs…”

Neighbors to Collaborators

The early Sinhala talkies carried a heavy South Indian influence and went on to perform well at the box office. Many directors and producers of Sinhala films were Tamil or South Indian. S.M. Nayagam, the producer of Kadawunu Poronduwa was a Tamil hailing from Madras Presidency (now Madurai). Nayagam was not a stranger to Ceylon. In fact, he was already invested in the island through his business ventures. (Apart from films, Nayagam also made bars of soap!)

Since early production work happened in South Indian studios, Nayagam ferried the whole cast of Kadawunu Poronduwa, Rukmani Devi, the brothers B.A.W. Jayamanne and Eddie Jayamanne, and the Minerva Theatre Group across the strait over to India. The film was directed by Jyotish Singh, a Bengali already working in the Tamil film industry. The music was directed by Narayana Aiyar, a musician of repute from Tamil Nadu.

Gujarati director V.N. Javeri, A.B. Raj who directed six Sinhala films, T.R. Sundaram, L.S. Ramachandran, A.S. Nagarajan of Mathalan fame were all directors of Indian origin who worked on Sinhala talkies. Mathalan ran for 90 days when it was first released in 1955 and for 118 days when it was re-screened in 1973, a record in local cinema. Similar to many other films of the era it was a copy of a Tamil film based on a folktale from Tanjore. It is claimed that a similar folk tale exists in Ceylon as well, pointing to the inextricable cultural common ground between South India and Ceylon. Audiences focused on these cultural ‘connectors’, more than they did on the ‘dividers’, as they embraced the song, dance and high drama. Perhaps it can also be inferred that cinema provided an escape from a divided reality.

Cinema Made by Everyone for Everyone

The contributions of the Muslim community to film, especially film music, is worthy of a movie of its own. Abdul Aziz of Kollupitiya, Mohamad Ghouse of Grandpass, Ismail Rauther of Moor Street, and Lakshmi Bhai, an idol of Nurti theater in the 30s and 40s, all contributed their musical talents. After the decline of Nurti theater, prominent artistes and music directors such as Ghouse Master, Peer Mohamed, Mohideen Baig and Abdul Haq defined and pioneered Sri Lankan music and cinema together with their Sinhala protégées and contemporaries including Amaradeva from the early 1930s to mid-60s.

Muslim musicians and singers, notably Mohamad Sali, Ibrahim Sali, A.J. Karim, M.A. Latif and K.M.A. Zawahir, also contributed significantly to radio broadcasting, serving in the orchestras of the Sri Lanka Broadcasting Corporation (SLBC). Very few are aware of Gnai Seenar Bangsajayah, popularly known as G.S.B. Rani, who is actually of Malay origins hailing from Badulla and gifted the island with unforgettable love songs.

To date, devotional songs such as ‘Buddham Saranam Gachchami’ sung by Mohideen Baig in qawwali style shape the Buddhist imagination and sentiment. Lakshmi Bhai’s ‘Pita Deepa Desha Jayagaththa, Aadi Sinhalun’ evokes a sense of patriotism many can relate to, despite the lyrics specifying the Sinhalese as those who won the world in the past.

The first director of Ceylon Tamil origin was T. Somasekaran whose box office hit Sujatha (1953) brought in a new age in film marketing. Another famous father-and-son duo from Jaffna were W.M.S. Tampoe and Robin Tampoe who directed many famous Sinhala films between them in the 1950s and 1960s. Premnath Moraes, S. Sivanandan and K. Gunaratnam are other pioneering Sri Lankan Tamil contributors to the Sinhala film industry.

One wonders why so many Tamil-speaking producers, directors and composers made films in Sinhala, and not in Tamil. The explanation is simple – the economics of the industry. South India produced a steady line of films in Tamil for the audiences in Ceylon. For Sri Lankan producers and filmmakers at the time, even when they themselves were Tamil-speaking, “this language issue” did not matter. Money was to be made with Sinhala audiences.

Even as individuals, it was easier to transcend ethnic and religious affiliations when it came to cinema. Mohideen Beig, a devout Muslim, was capable of surrendering to Buddha in his songs with utter sincerity. ‘Buddham Saranam Gachchami’, one of his popular devotional songs, is played at Vesak festivals every year: “to Buddha, my only refuge, I surrender”.

As individuals, as communities and as industries, we embraced diversity intuitively and subconsciously. In the 1950s there was a slow reversal of this configuration, where identity politics insidiously began to take over the island, and even seeping into the film industry. As in all other aspects, this spelt doom for the Sri Lankan film. The nationalization of cinema through the establishment of the National Film Corporation in the 1970s, brought in strict government control to an industry that flourished with freedom and creativity. The space for different communities to contribute to the industry shrank steadily.

The Legacy of Love and Hate

The film Asokamala was an early victim of this trend. One could argue that the barrage of shrill film reviews published in the dailies criticizing the film provide early specimens of what is known today as hate speech.

Asokamala (1947) is the Romeo Juliet of the island’s historic love stories. In its essence, the film is an allegory of the island. Produced by a Tamil (Gardiner), directed by a Sinhalese (Shantikumar Seneviratne), the film’s musical score was produced by a Muslim, Mohommed Ghouse, affectionately called Ghouse Master. The film introduced both Mohideen Beig (Muslim) and Amaradeva (Sinhalese) as playback singers. Indian songstress Bhagyarathi stepped in for G.S.B. Rani (Malay), who could not make it to the recordings at Central Studios, Coimbatore India. The film drew the best of Sri Lankan talent, from all its communities and its neighbors.

The theme of the film itself hinted at reconciliation between different communities. Prince Saliya, the son of King Dutugemunu, a celebrated heroic figure from the second century BCE, falls in love with a damsel from a marginal caste. He chooses love over power, and is willing to reconcile with the Tamil chieftains whom his father defeated in a great war, a central albeit controversial event in the island’s history. Released a year before the island gained independence from colonial rulers, the film was almost a prophetic missive highlighting the challenges and opportunities ahead. It went on to earn five times its financial investment and was replete with musical hits known across generations.

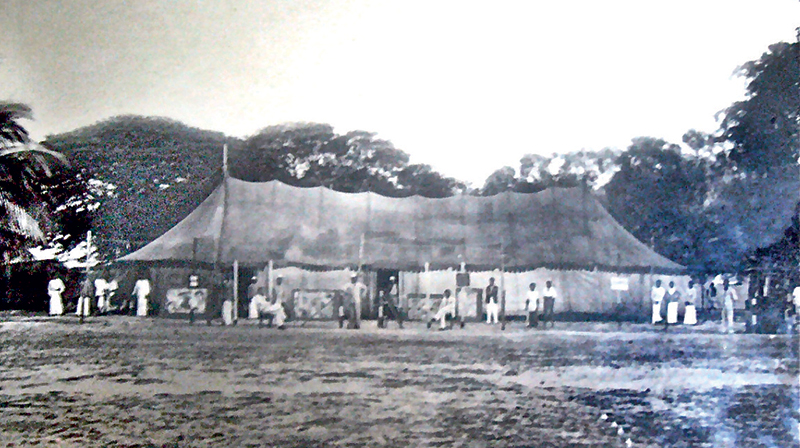

- 1962. Sound Recording by Ceylonese crew in South India

- Film pioneer Sir Chittampalam A. Gardiner

However, rising nationalist elements found the film unacceptable. Despite its many plus points, the film was severely criticized in newspapers such as Dinamina, Silumina, Sinhala Baudhdhya, Sinhala Balaya and Sarasavi Sandaresa to name a few.

‘Asokamala is a corruption of history, as it goes against its historical time period and its motherland. It is a story set in the ancient Buddhist capital of Anuradhapura, but nowhere in the film can you see Buddhist stupas, or Buddhist monks. In this film, Dutugemunu is a weak old man,’ a Silumina newspaper editorial (27 April, 1947) lashed out.

‘What we hear about the film currently being shown at the theaters in Colombo is that it hurls abuse and insults at the entire Sinhala race. No Sinhala person would remain silent when the greatest warrior and supreme Sinhala Buddhist ruler is portrayed as a weakling and coward in this film,’

clamored Sarasavi Sandaresa.

In the same editorial, the newspaper urged all Sinhalese Buddhists to boycott the film. In fact, it is amidst this outcry against Asokamala that the idea of establishing a national regulatory body for films was mooted. A love story became a locus of hatred.

This sinister trend for purity and Buddhist supremacy led to many catastrophes over the decades. Communities who once lived in close proximity, who shared neighborhoods and homes and memories became estranged, as seen in the story of Mr Dharmalingam. Cinemas like Rio, owned by minority communities were burnt down in riots.

In reflection, what is most surprising is how powerful stories – positive stories – are repressed through such trends. Today, we remain largely unaware that the first Sinhala film was produced by a Tamil. And hundreds of Sinhala songs were composed by Muslim musicians and sung by Muslims and Malays. We hail Rukamani Devi as the Queen of the Silver Screen, but forget that her real name was Daisy Rasammah Daniel and that she performed in all three languages.

These stories are recorded in black and white, in sound and visual and yet remain unacknowledged, forgotten and dismissed. Nationalism binds people through one story but also blinds people to many other narratives. The early days of Sri Lankan cinema present a host of stories that illustrate confluence. The sheer number of Tamil, Muslim, Bohra, Burgher, Malay, Colombo Chetty communities working together with Sinhalese for the cinematic industry is not just ‘a possibility’ but a reality that already existed. One only needs to read the credits of an old movie, and ask who is who.

These stories are parables on how harmony makes small things grow; and how the lack of it makes great things decay. Cinema created a space for people to not just coexist but collaborate. A sanctuary where people could transcend parochial identities, unleash their creative potential and find their own purpose and place in history. What made cinema a truly modern form of art, is not the technology, but that it brought together this multitude of people, talents, arts, sciences, commerce, and vision in its wake.

Likewise, the opportunity of becoming a modern democratic state lies in proactively focusing and celebrating this diversity and opting for the path of love, collaboration, appreciation and deep understanding as opposed to hate. Coexistence is not a passive state but an active, changing dynamic that requires constant effort.

It is said in the movies that love and hate are two sides of the same coin. Is this really true? Or are they distinctive paths we must choose from, individually and collectively, as we walk into our futures?

Features

Sheer rise of Realpolitik making the world see the brink

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

The recent humanly costly torpedoing of an Iranian naval vessel in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone by a US submarine has raised a number of issues of great importance to international political discourse and law that call for elucidation. It is best that enlightened commentary is brought to bear in such discussions because at present misleading and uninformed speculation on questions arising from the incident are being aired by particularly jingoistic politicians of Sri Lanka’s South which could prove deleterious.

As matters stand, there seems to be no credible evidence that the Indian state was aware of the impending torpedoing of the Iranian vessel but these acerbic-tongued politicians of Sri Lanka’s South would have the local public believe that the tragedy was triggered with India’s connivance. Likewise, India is accused of ‘embroiling’ Sri Lanka in the incident on account of seemingly having prior knowledge of it and not warning Sri Lanka about the impending disaster.

It is plain that a process is once again afoot to raise anti-India hysteria in Sri Lanka. An obligation is cast on the Sri Lankan government to ensure that incendiary speculation of the above kind is defeated and India-Sri Lanka relations are prevented from being in any way harmed. Proactive measures are needed by the Sri Lankan government and well meaning quarters to ensure that public discourse in such matters have a factual and rational basis. ‘Knowledge gaps’ could prove hazardous.

Meanwhile, there could be no doubt that Sri Lanka’s sovereignty was violated by the US because the sinking of the Iranian vessel took place in Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone. While there is no international decrying of the incident, and this is to be regretted, Sri Lanka’s helplessness and small player status would enable the US to ‘get away with it’.

Could anything be done by the international community to hold the US to account over the act of lawlessness in question? None is the answer at present. This is because in the current ‘Global Disorder’ major powers could commit the gravest international irregularities with impunity. As the threadbare cliché declares, ‘Might is Right’….. or so it seems.

Unfortunately, the UN could only merely verbally denounce any violations of International Law by the world’s foremost powers. It cannot use countervailing force against violators of the law, for example, on account of the divided nature of the UN Security Council, whose permanent members have shown incapability of seeing eye-to-eye on grave matters relating to International Law and order over the decades.

The foregoing considerations could force the conclusion on uncritical sections that Political Realism or Realpolitik has won out in the end. A basic premise of the school of thought known as Political Realism is that power or force wielded by states and international actors determine the shape, direction and substance of international relations. This school stands in marked contrast to political idealists who essentially proclaim that moral norms and values determine the nature of local and international politics.

While, British political scientist Thomas Hobbes, for instance, was a proponent of Political Realism, political idealism has its roots in the teachings of Socrates, Plato and latterly Friedrich Hegel of Germany, to name just few such notables.

On the face of it, therefore, there is no getting way from the conclusion that coercive force is the deciding factor in international politics. If this were not so, US President Donald Trump in collaboration with Israeli Rightist Premier Benjamin Natanyahu could not have wielded the ‘big stick’, so to speak, on Iran, killed its Supreme Head of State, terrorized the Iranian public and gone ‘scot-free’. That is, currently, the US’ impunity seems to be limitless.

Moreover, the evidence is that the Western bloc is reuniting in the face of Iran’s threats to stymie the flow of oil from West Asia to the rest of the world. The recent G7 summit witnessed a coming together of the foremost powers of the global North to ensure that the West does not suffer grave negative consequences from any future blocking of western oil supplies.

Meanwhile, Israel is having a ‘free run’ of the Middle East, so to speak, picking out perceived adversarial powers, such as Lebanon, and militarily neutralizing them; once again with impunity. On the other hand, Iran has been bringing under assault, with no questions asked, Gulf states that are seen as allying with the US and Israel. West Asia is facing a compounded crisis and International Law seems to be helplessly silent.

Wittingly or unwittingly, matters at the heart of International Law and peace are being obfuscated by some pro-Trump administration commentators meanwhile. For example, retired US Navy Captain Brent Sadler has cited Article 51 of the UN Charter, which provides for the right to self or collective self-defence of UN member states in the face of armed attacks, as justifying the US sinking of the Iranian vessel (See page 2 of The Island of March 10, 2026). But the Article makes it clear that such measures could be resorted to by UN members only ‘ if an armed attack occurs’ against them and under no other circumstances. But no such thing happened in the incident in question and the US acted under a sheer threat perception.

Clearly, the US has violated the Article through its action and has once again demonstrated its tendency to arbitrarily use military might. The general drift of Sadler’s thinking is that in the face of pressing national priorities, obligations of a state under International Law could be side-stepped. This is a sure recipe for international anarchy because in such a policy environment states could pursue their national interests, irrespective of their merits, disregarding in the process their obligations towards the international community.

Moreover, Article 51 repeatedly reiterates the authority of the UN Security Council and the obligation of those states that act in self-defence to report to the Council and be guided by it. Sadler, therefore, could be said to have cited the Article very selectively, whereas, right along member states’ commitments to the UNSC are stressed.

However, it is beyond doubt that international anarchy has strengthened its grip over the world. While the US set destabilizing precedents after the crumbling of the Cold War that paved the way for the current anarchic situation, Russia further aggravated these degenerative trends through its invasion of Ukraine. Stepping back from anarchy has thus emerged as the prime challenge for the world community.

Features

A Tribute to Professor H. L. Seneviratne – Part II

A Living Legend of the Peradeniya Tradition:

(First part of this article appeared yesterday)

H.L. Seneviratne’s tenure at the University of Virginia was marked not only by his ethnographic rigour but also by his profound dedication to the preservation and study of South Asian film culture. Recognising that cinema is often the most vital expression of a society’s aspirations and anxieties, he played a central role in curating what is now one of the most significant Indian film collections in the United States. His approach to curation was never merely archival; it was informed by his anthropological work, treating films as primary texts for understanding the ideological shifts within the subcontinent

The collection he helped build at the UVA Library, particularly within the Clemons Library holdings, serves as a comprehensive survey of the Indian ‘Parallel Cinema’ movement and the works of legendary auteurs. This includes the filmographies of directors such as Satyajit Ray, whose nuanced portrayals of the Indian middle class and rural poverty provided a cinematic counterpart to H.L. Seneviratne’s own academic interests in social change. By prioritising the works of figures such as Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak, H.L. Seneviratne ensured that students and scholars had access to films that wrestled with the complex legacies of colonialism, partition, and the struggle for national identity.

These films represent the ‘Parallel Cinema’ movement of West Bengal rather than the commercial Hindi industry of Mumbai. H.L. Seneviratne’s focus initially cantered on those world-renowned Bengali masters; it eventually broadened to encompass the distinct cinematic languages of the South. These films refer to the specific masterpieces from the Malayalam and Tamil regions—such as the meditative realism of Adoor Gopalakrishnan or the stylistic innovations of Mani Ratnam—which are culturally and linguistically distinct from the Bengali works. Essentially, H.L. Seneviratne is moving from the specific (Bengal) to the panoramic, ensuring that the curatorial work of H.L. Seneviratne was not just a ‘Greatest Hits of Kolkata’ but a truly national representation of Indian artistry. These films were selected for their ability to articulate internal critiques of Indian society, often focusing on issues of caste, gender, and the impact of modernisation on traditional life. Through this collection, H.L. Seneviratne positioned cinema as a tool for exposing the social dynamics that often remain hidden in traditional historical records, much like the hidden political rituals he uncovered in his early research.

Beyond the films themselves, H.L. Seneviratne integrated these visual resources into his curriculum, fostering a generation of scholars who understood the power of the image in South Asian politics. He frequently used these screenings to illustrate the conflation of past and present, showing how modern cinema often reworks ancient myths to serve contemporary political agendas. His legacy at the University of Virginia therefore encompasses both a rigorous body of writing that deconstructed the work of the kings and a vivid archive of films that continues to document the work of culture in a rapidly changing world.

In his lectures on Sri Lankan cinema, H.L. Seneviratne has frequently championed Lester James Peries as the ‘father of authentic Sinhala cinema.’ He views Peries’s 1956 film Rekava (Line of Destiny) as a watershed moment that liberated the local industry from the formulaic influence of South Indian commercial films. For H.L. Seneviratne, Peries was not just a filmmaker but an ethnographer of the screen. He often points to Peries’s ability to capture the subtle rhythms of rural life and the decline of the feudal elite, most notably in his masterpiece Gamperaliya, as a visual parallel to his own research into the transformation of traditional authority. H.L. Seneviratne argues that Peries provided a realistic way of seeing for the nation, one that eschewed nationalist caricature in favour of complex human emotion.

However, H.L. Seneviratne’s praise for Peries is often tempered by a critique of the broader visual nationalism that followed. He has expressed concern that later filmmakers sometimes misappropriated Peries’s indigenous style to promote a narrow, majoritarian view of history. In his view, while Peries opened the door to an authentic Sri Lankan identity, the state and subsequent commercial interests often used that same door to usher in a simplified, heroic past. This critique aligns with his broader academic stance against the rationalization of culture for political ends.

Constitutional Governance:

H.L. Seneviratne’s support for independent commissions is best described as a hopeful pragmatism; he views them as essential, albeit fragile, instruments for diffusing the hyper-concentration of executive power. Writing to Colombo Page and several news tabloids, H.L. Seneviratne addresses the democratic deficit by creating a structural buffer between partisan interests and public institutions, theoretically ensuring that the judiciary, police, and civil service operate on merit rather than political whim. However, he remains deeply aware that these commissions are not a panacea and are indeed inherently susceptible to the ‘politics of patronage.’

In cultures where power is traditionally exercised through personal loyalties, there is a constant risk that these bodies will be subverted through the appointment of hidden partisans or rendered toothless through administrative sabotage. Thus, while H.L. Seneviratne advocates for them as a means to transition a state from a patron-client culture to a rule-of-law framework, his anthropological lens suggests that the success of such commissions depends less on the law itself and more on the sustained pressure of civil society to keep them honest.

Whether discussing the nuances of a film’s narrative or the complexities of a constitutional clause, H.L. Seneviratne’s approach remains consistent in its focus on the spirit behind the institution. He maintains that a healthy democracy requires more than just the right laws or the right symbols; it requires a citizenry and a clergy capable of critical self-reflection. His career at the University of Virginia and his continued engagement with Sri Lankan public life stand as a testament to the idea that the intellectual’s work is never truly finished until the work of the people is fully realized.

In the context of H.L. Seneviratne’s philosophy, as discussed in his work of the kings ‘the work of the people’ is far more than a populist catchphrase; it represents the practical application of critical consciousness within a democracy. Rather than defining ‘work’ as labour or voting, H.L. Seneviratne views it as the transition of a population from passive subjects to an active, self-reflective citizenry. This means that a democracy is only truly ‘realized’ when the public possesses the intellectual autonomy to look beyond the ‘right laws’ or ‘right symbols’ and instead engage with the underlying spirit of their institutions. For H.L. Seneviratne, this work is specifically tied to the ability of the people—including influential groups like the clergy—to perform rigorous self-critique, ensuring that they are not merely following tradition or authority, but are actively sustaining the ethical health of the nation. It is a perpetual process of civic education and moral vigilance that moves a society from the ‘paper’ democracy of a constitution to a lived reality of accountability and insight.

This decline of the ‘intellectual monk’ had a catastrophic impact on the political landscape, particularly surrounding the watershed moment of 1956 and the ‘Sinhala Only’ movement. H.L. Seneviratne posits that when the Sangha exchanged their role as impartial moral advisors for that of political kingmakers, they became the primary obstacle to ethnic reconciliation. He suggests that politicians, fearing the immense grassroots influence of the monks, entered a state of monachophobia, where they felt unable to propose pluralistic or fair policies toward minority communities for fear of being branded as traitors to the faith. In H.L. Seneviratne’s framework, the monk’s transition from a social servant to a political vanguard effectively trapped the state in a cycle of majoritarian nationalism from which it has yet to escape.

H.L. Seneviratne’s work serves as a multifaceted critique of the modern Sri Lankan state and its cultural foundations. Whether he is dissecting what he sees as the betrayal of the monastic ideal or celebrating the humanistic vision of an Indian filmmaker, his goal remains the same: to champion a world where intellect and compassion are not sacrificed on the altar of political power. His legacy at the University of Virginia and his continued voice in Sri Lankan discourse remind us that the work of the intellectual is to provide a moral compass even, indeed especially, when the nation has lost its way.

(Concluded)

by Professor

M. W. Amarasiri de Silva

Features

Musical journey of Nilanka Anjalee …

Nilanka Anjalee Wickramasinghe is, in fact, a reputed doctor, but the plus factor is that she has an awesome singing voice, as well., which stands as a reminder that music and intellect can harmonise beautifully.

Nilanka Anjalee Wickramasinghe is, in fact, a reputed doctor, but the plus factor is that she has an awesome singing voice, as well., which stands as a reminder that music and intellect can harmonise beautifully.

Well, our spotlight today is on ‘Nilanka – the Singer,’ and not ‘Nilanka – the Singing Doctor!’

Nilanka’s journey in music began at an early age, nurtured by an ear finely tuned to nuance and a heart that sought expression beyond words.

Under the tutelage of her singing teachers, she went on to achieve the A.T.C.L. Diploma in Piano and the L.T.C.L. Diploma in Vocals from Trinity College, London – qualifications recognised internationally for their rigor and artistry.

These achievements formally certified her as a teacher and performer in both opera singing and piano music, while her Performer’s Certificate for singing attested to her flair on stage.

Nilanka believes that music must move the listener, not merely impress them, emphasising that “technique is a language, but emotion is the message,” and that conviction shines through in her stage presence –serene yet powerful, intimate yet commanding.

Her YouTube channel, Facebook and Instagram pages, “Nilanka Anjalee,” have become a window into her evolving artistry.

Here, audiences find not only her elegant renditions of local and international pieces but also her original songs, which reveal a reflective and modern voice with a timeless sensibility.

Each performance – whether a haunting ballad or a jubilant interpretation of a traditional hymn – carries her signature blend of technical finesse and emotional depth.

Beyond the concert hall and digital stage, Nilanka’s music is driven by a deep commitment to meaning.

Her work often reflects her belief in empathy, inner balance, and the beauty of simplicity—values that give her performances their quiet strength.

She says she continues to collaborate with musicians across genres, composing and performing pieces that reflect both her classical discipline and her contemporary outlook.

Widely acclaimed for her ability to adapt to both formal and modern stages, with equal grace, and with her growing repertoire, Nilanka has become a sought-after soloist at concerts and special events,

For those who seek to experience her artistry, firsthand, Nilanka Anjalee says she can be contacted for live performances and collaborations through her official channels.

Her voice – refined, resonant, and resolutely her own – reminds us that music, at its core, is not about perfection, but truth.

Dr. Nilanka Anjalee Wickramasinghe also indicated that her newest single, an original, titled ‘Koloba Ahasa Yata,’ with lyrics, melody and singing all done by her, is scheduled for release this month (March)

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoUniversity of Wolverhampton confirms Ranil was officially invited

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPeradeniya Uni issues alert over leopards in its premises

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoFemale lawyer given 12 years RI for preparing forged deeds for Borella land

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoRepatriation of Iranian naval personnel Sri Lanka’s call: Washington

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoLibrary crisis hits Pera university

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoWife raises alarm over Sallay’s detention under PTA

-

News7 days ago

News7 days ago‘IRIS Dena was Indian Navy guest, hit without warning’, Iran warns US of bitter regret

-

Latest News7 days ago

Latest News7 days agoSri Lanka evacuates crew of second Iranian vessel after US sunk IRIS Dena