Features

The old Thomian who led Kumana villagers

Excerpts from P Dayaratne’s autobiography

by KKS PERERA

While translating the Sinhala autobiography of P. Dayaratne, the former District and Cabinet Minister who represented Ampara (Digamadulla) in Parliament for an uninterrupted 38 years, this writer came across an intriguing chapter featuring a vivid recollection of the Kumana bird sanctuary located to the east of the Yala National Park, which is the largest natural resource in Panampattuwa.

Its community leader was Charles Lambert Leonidas, an alumnus of St. Thomas’, the renowned school by the sea, according to Dayaratne, a gentle and dignified politician. Evidence suggests the people of Kumana village have lived there for generations, with some possibly being descendants of those who fled following the Uva-Wellassa rebellion.

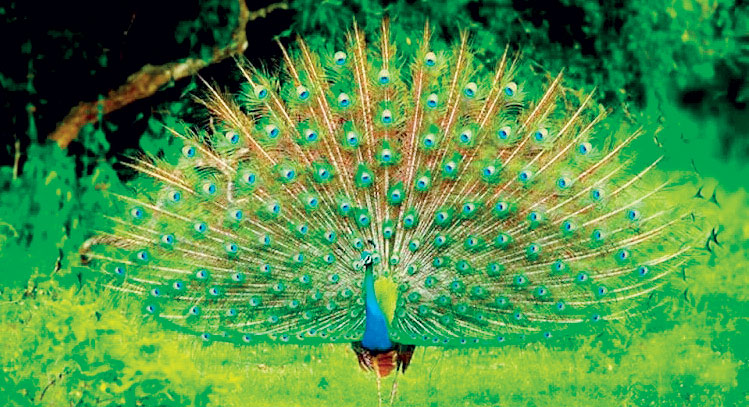

The Kumana bird sanctuary, located on the eastern side of Yala National Park, is one of Panama’s greatest natural treasures. Dayaratne, deeply passionate about environmental conservation, played a key role in preserving this invaluable sanctuary.

Leonidas opposed relocation

Dayaratne was aware of Leonidas, a Thomian fluent in English, who was well-liked by tourists. Initially appointed as an English teacher at Panama Maha Vidyalaya, Leonidas was later transferred to a school in Kumana after conflicts with the Batticaloa education authorities. Panampattuwa is rich in ancient sites reclaimed by the wilderness, including Kotavehera, Bambaragastalawa, Kongaswewa, and Karanda Hela. While scholars must research and interpret these sites, their preservation is a duty of the local community, with legal protection being the government’s responsibility.

Dayaratne, an electrical engineer with a deep passion for nature, regarded the Kumana bird sanctuary as a national treasure. The bird colonies in its lagoons are among Asia’s most significant, offering both an ecological resource and a breathtaking sight for nature enthusiasts. Migratory birds from Siberia reach Kumana as their final stop, with no landmass further south—a phenomenon still studied by scientists.

Kumana’s villagers thrived entirely off the forest, facing fewer challenges than those in developed areas. They gathered honey, hunted deer and buffalo, and sold wood apples to buy essentials like salt and dried fish. Living simply, they had little interest in luxury. Unlike other voters, they made no demands for electricity, piped water, or telephones, yet remained content—a way of life Dayaratne deeply admired.

In contrast, the lifestyle in other regions was vastly different. People there worked tirelessly day and night to accumulate wealth, constantly striving for positions, rank and status. When their expectations were unmet, they complained, harbored resentment, and felt envy. Some even plotted against others. However, such traits were absent among the people of Kumana. They led simple lives, coexisting harmoniously as an interconnected community where everyone was related to one another.

Panama is home to many ancient sites overgrown by nature. Among them, Kotavehera, Bambaragasthalawa, Kongaswewa, and Karandahela stand out as significant locations. While scholars are responsible for conducting research and providing historical analyses of these sites, it is the commitment of the local communities that ensures their preservation. The government, in turn, must enforce appropriate legal measures to protect them says, the former minister.

During his time in Kumana, Leonidas married a young woman from the village. However, his arrogant nature eventually led to his downfall. While he was a leader to the uneducated villagers, his command of English enabled him to mediate between the villagers and visiting government officials or politicians at the Kumuna Sanctuary. Through these connections, he was able to facilitate certain benefits for the local people.

Leonidas opposed relocation of Kumana villagers Living within a wildlife reserve. Before becoming Minister of Mahaweli Development, Dayaratne had attempted to relocate the Kumana villagers to another area, but his efforts were unsuccessful. Previous ministers had also attempted this relocation plan but failed. Despite the Department of Wildlife Conservation’s urgent program to remove the Kumana settlement, their efforts were thwarted by human rights organizations that opposed the move.

Thirty houses were built near Kudumbigala Aranya Senasana to relocate Kumana villagers during State Minister Anandatissa de Alwis’s tenure. However, the project failed—elephants destroyed most houses, and looters stole the materials.

Developing Kumana was difficult. Despite Dayaratne’s efforts as Minister of Mahaweli Development, strict Wildlife Conservation regulations restricted land use, leading him to consider relocating villagers to Mahaweli settlements. Ven. Thambugala Anandasiri Thero, the former head monk of Kudumbigala, transformed the rugged area into a haven for meditative monks. Tragically, Sinhala extremists assassinated him, despite his political neutrality. Dayaratne, who knew him personally, mourned his loss.

At the Mahaweli Ministry, Dayaratne found the Mahaweli Authority and the Wildlife Department merged under a single ministry, easing coordination. Seeing an opportunity, he pursued the Kumana resettlement project. However, a foreigner residing in Kumana fiercely opposed it. Undeterred, Dayaratne remained committed to relocating the villagers for their well-being.

Around this time, President Ranasinghe Premadasa visited the Eastern Province, providing Dayaratne with an opportunity to push his forward his agenda. He proposed to the President that they visit Kumana, and Premadasa agreed. Traveling there by helicopter, they encountered villagers who were hesitant to travel through the jungle to Panama due to fears of terrorist attacks.

A meeting was arranged between the President and the villagers, during which the proposal to relocate them to the Mahaweli settlements was presented. Leonidas, as the de facto village leader, firmly refused to leave Kumana, accusing the government of attempting a forced eviction. President Premadasa listened attentively to all arguments.

Dayaratne then explained to the President the benefits that would be provided to those who agreed to relocate. Each family would receive two acres of paddy land and half an acre of highland, with roads built to ensure access to their new homes. Additionally, they would receive financial assistance until their first harvest. Despite these assurances, Leonidas remained adamantly opposed to the plan. President Premadasa, taking all factors into account, carefully considered the next course of action.

Dayaratne ensured that all necessary relief was provided, yet there was no indication that Leonidas would withdraw his opposition. President Premadasa remained unmoved. It is likely that the President believed Leonidas was merely representing the sentiments of the villagers. Even Dayaratne himself considered Leonidas’ love for the village and his perspective to be justifiable. However, allowing people to reside within a national park was entirely unacceptable, as it offered them no prospect of development.

While the situation remained tense, a young man seated at the back suddenly stood up and declared that, apart from six families, all others were willing to leave the village and relocate to the Mahaweli lands. A sense of relief washed over Dayaratne upon hearing this statement. There was little Leonidas could argue against, as only six families remained in support of his stance. Eventually, about 25 families were relocated to Mahaweli territory.

At that time, the Department of Wildlife managed two tourist bungalows in Okanda and Thunmulle, but both were destroyed by insurgents during a period of intense terrorist activity. As violence escalated, Leonidas and six families who had initially refused to move were forced to abandon the village and seek refuge in Panama.

Later, news spread that Leonidas had died suddenly on the grounds of Panama Maha Vidyalaya at around 80-years of age.

Dayasena was the son of Kiriya Piyadasa, a respected village leader in Kumana who owned a small shop. Piyadase was beloved by the villagers and ensured that his daughter, Podi Nona, received her education at Vishaka Vidyalaya in Badulla. Upon completing her studies, Piyadasa helped her secure a teaching position during President Premadasa’s tenure. She later became the principal of the Kumana village school and ensured her children received quality education by enrolling them in Badulla schools.

At that time, appointing a Grama Niladhari for Kumana was challenging. The village’s administration was handled by the officer from Panama, 23 miles away. Although separate officers were occasionally appointed, none were willing to serve in Kumana. To resolve this, the Minister of Public Administration, Montague Jayawickrame, submitted a special cabinet paper, leading to Piyadasa Dayasena’s appointment as Grama Niladhari despite his limited qualifications.

Podi Nona’s daughters to England

One of Podi Nona’s daughters eventually migrated to England and built a successful life there. Dayaratne learned of this when he and his wife met her in Colombo. She expressed gratitude for the opportunities that had shaped her family’s future, emphasizing that had they remained in the dense forests of Kumana, such progress would have been impossible. She also mentioned that her parents had received land in the Mahaweli region which had transformed their lives.

Tragically, in the eastern region, a group of wildlife officers, including the Assistant Director of Wildlife, was brutally murdered by terrorists in Kumana. This incident severely disrupted the Wildlife Department’s operations in the area.

The primary sources of income in Panama were paddy farming and chena cultivation, with some villagers also engaged in fishing. In earlier times, a few resorted to hunting for food. However, with the rise of LTTE terrorism, hunting ceased entirely as people avoided venturing into the forest for fear of both terrorists and the Special Task Force (STF). From an environmental perspective, the writer found relief in knowing that wildlife had been spared from further hunting.

The people of Panama led simple, peaceful lives. Due to the village’s isolation, they were slow to adopt modern social changes. It remains uncertain whether any other village in the country could compare to Panama in terms of its seclusion and traditional way of life.

Dayaratne recalled the kindness shown to him by several individuals in this village over the years. Some actively supported his electoral campaigns, while others were respected figures who had held key positions in the community. Among them, he specifically remembered two old friends: Heen Banda Somasundaram and N.J. Dhanabalasingham, whose generous hospitality he deeply appreciated. He also acknowledged political activists such as Kanakasabe, Gunaratna, Obeysekera, Dinaratna, Kalubanda, and Wijerathna, all of whom had since passed away. Dinaratna, notably, had been married to Heen Banda Somasundaram’s daughter.

In subsequent years, Babban Appu Jayathilaka, Rasaiah Chandrasena, and Lalee Kulnayake emerged as prominent activists. Babban Appu Jayathilaka, who contested under the United National Party, had served as chairman of the Lahugala Pradeshiya Sabha for a time. Rasaiah Chandrasena, a teacher by profession, later held the same position after winning an election.

kksperera1@gmail.com

Features

Cyclones, greed and philosophy for a new world order

Further to my earlier letter titled, “Psychology of Greed and Philosophy for a New World Order” (The Island 26.11.2025) it may not be far-fetched to say that the cause of the devastating cyclones that hit Sri Lanka and Indonesia last week could be traced back to human greed. Cyclones of this magnitude are said to be unusual in the equatorial region but, according to experts, the raised sea surface temperatures created the conditions for their occurrence. This is directly due to global warming which is caused by excessive emission of Greenhouse gases due to burning of fossil fuels and other activities. These activities cannot be brought under control as the rich, greedy Western powers do not want to abide by the terms and conditions agreed upon at the Paris Agreement of 2015, as was seen at the COP30 meeting in Brazil recently. Is there hope for third world countries? This is why the Global South must develop a New World Order. For this purpose, the proposed contentment/sufficiency philosophy based on morals like dhana, seela, bhavana, may provide the necessary foundation.

Further, such a philosophy need not be parochial and isolationist. It may not be necessary to adopt systems that existed in the past that suited the times but develop a system that would be practical and also pragmatic in the context of the modern world.

It must be reiterated that without controlling the force of collective greed the present destructive socioeconomic system cannot be changed. Hence the need for a philosophy that incorporates the means of controlling greed. Dhana, seela, bhavana may suit Sri Lanka and most of the East which, as mentioned in my earlier letter, share a similar philosophical heritage. The rest of the world also may have to adopt a contentment / sufficiency philosophy with strong and effective tenets that suit their culture, to bring under control the evil of greed. If not, there is no hope for the existence of the world. Global warming will destroy it with cyclones, forest fires, droughts, floods, crop failure and famine.

Leading economists had commented on the damaging effect of greed on the economy while philosophers, ancient as well as modern, had spoken about its degenerating influence on the inborn human morals. Ancient philosophers like Plato, Aristotle, and Epicurus all spoke about greed, viewing it as a destructive force that hindered a good life. They believed greed was rooted in personal immorality and prevented individuals from achieving true happiness by focusing on endless material accumulation rather than the limited wealth needed for natural needs.

Jeffry Sachs argues that greed is a destructive force that undermines social and environmental well-being, citing it as a major driver of climate change and economic inequality, referencing the ideas of Adam Smith, John Maynard Keynes, etc. Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel Laureate economist, has criticised neoliberal ideology in similar terms.

In my earlier letter, I have discussed how contentment / sufficiency philosophy could effectively transform the socioeconomic system to one that prioritises collective well-being and sufficiency over rampant consumerism and greed, potentially leading to more sustainable economic models.

Obviously, these changes cannot be brought about without a change of attitude, morals and commitment of the rulers and the government. This cannot be achieved without a mass movement; people must realise the need for change. Such a movement would need leadership. In this regard a critical responsibility lies with the educated middle class. It is they who must give leadership to the movement that would have the goal of getting rid of the evil of excessive greed. It is they who must educate the entire nation about the need for these changes.

The middle class would be the vanguard of change. It is the middle class that has the capacity to bring about change. It is the middle class that perform as a vibrant component of the society for political stability. It is the group which supplies political philosophy, ideology, movements, guidance and leaders for the rest of the society. The poor, who are the majority, need the political wisdom and leadership of the middle class.

Further, the middle class is the font of culture, creativity, literature, art and music. Thinkers, writers, artistes, musicians are fostered by the middle class. Cultural activity of the middle class could pervade down to the poor groups and have an effect on their cultural development as well. Similarly, education of a country depends on how educated the middle class is. It is the responsibility of the middle class to provide education to the poor people.

Most importantly, the morals of a society are imbued in the middle class and it is they who foster them. As morals are crucial in the battle against greed, the middle class assume greater credentials to spearhead the movement against greed and bring in sustainable development and growth. Contentment sufficiency philosophy, based on morals, would form the strong foundation necessary for achieving the goal of a new world order. Thus, it is seen that the middle class is eminently suitable to be the vehicle that could adopt and disseminate a contentment/ sufficiency philosophy and lead the movement against the evil neo-liberal system that is destroying the world.

The Global South, which comprises the majority of the world’s poor, may have to realise, before it is too late, that it is they who are the most vulnerable to climate change though they may not be the greatest offenders who cause it. Yet, if they are to survive, they must get together and help each other to achieve self-sufficiency in the essential needs, like food, energy and medicine. Trade must not be via exploitative and weaponised currency but by means of a barter system, based on purchase power parity (PPP). The union of these countries could be an expansion of organisations,like BRICS, ASEAN, SCO, AU, etc., which already have the trade and financial arrangements though in a rudimentary state but with great potential, if only they could sort out their bilateral issues and work towards a Global South which is neither rich nor poor but sufficient, contented and safe, a lesson to the Global North. China, India and South Africa must play the lead role in this venture. They would need the support of a strong philosophy that has the capacity to fight the evil of greed, for they cannot achieve these goals if fettered by greed. The proposed contentment / sufficient philosophy would form a strong philosophical foundation for the Global South, to unite, fight greed and develop a new world order which, above all, will make it safe for life.

by Prof. N. A. de S. Amaratunga

PHD, DSc, DLITT

Features

SINHARAJA: The Living Cathedral of Sri Lanka’s Rainforest Heritage

When Senior biodiversity scientist Vimukthi Weeratunga speaks of Sinharaja, his voice carries the weight of four decades spent beneath its dripping emerald canopy. To him, Sri Lanka’s last great rainforest is not merely a protected area—it is “a cathedral of life,” a sanctuary where evolution whispers through every leaf, stream and shadow.

“Sinharaja is the largest and most precious tropical rainforest we have,” Weeratunga said.

“Sixty to seventy percent of the plants and animals found here exist nowhere else on Earth. This forest is the heart of endemic biodiversity in Sri Lanka.”

A Magnet for the World’s Naturalists

Sinharaja’s allure lies not in charismatic megafauna but in the world of the small and extraordinary—tiny, jewel-toned frogs; iridescent butterflies; shy serpents; and canopy birds whose songs drift like threads of silver through the mist.

“You must walk slowly in Sinharaja,” Weeratunga smiled.

“Its beauty reveals itself only to those who are patient and observant.”

For global travellers fascinated by natural history, Sinharaja remains a top draw. Nearly 90% of nature-focused visitors to Sri Lanka place Sinharaja at the top of their itinerary, generating a deep economic pulse for surrounding communities.

A Forest Etched in History

Centuries before conservationists championed its cause, Sinharaja captured the imagination of explorers and scholars. British and Dutch botanists, venturing into the island’s interior from the 17th century onward, mapped streams, documented rare orchids, and penned some of the earliest scientific records of Sri Lanka’s natural heritage.

These chronicles now form the backbone of our understanding of the island’s unique ecology.

The Great Forest War: Saving Sinharaja

But Sinharaja nearly vanished.

In the 1970s, the government—guided by a timber-driven development mindset—greenlit a Canadian-assisted logging project. Forests around Sinharaja fell first; then, the chainsaws approached the ancient core.

“There was very little scientific data to counter the felling,” Weeratunga recalled.

- Poppie’s shrub frog

- Endemic Scimitar babblers

- Blue Magpie

“But people knew instinctively this was a national treasure.”

The public responded with one of the greatest environmental uprisings in Sri Lankan history. Conservation icons Thilo Hoffmann and Neluwe Gunananda Thera led a national movement. After seven tense years, the new government of 1977 halted the project.

What followed was a scientific renaissance. Leading researchers—including Prof. Savithri Gunathilake and Prof. Nimal Gunathilaka, Prof. Sarath Kottagama, and others—descended into the depths of Sinharaja, documenting every possible facet of its biodiversity.

“Those studies paved the way for Sinharaja to become Sri Lanka’s very first natural World Heritage Site,” Weeratunga noted proudly.

- Vimukthi

- Nadika

- Janaka

A Book Woven From 30 Years of Field Wisdom

For Weeratunga, Sinharaja is more than academic terrain—it is home. Since joining the Forest Department in 1985 as a young researcher, he has trekked, photographed, documented and celebrated its secrets.

Now, decades later, he joins Dr. Thilak Jayaratne, the late Dr. Janaka Gallangoda, and Nadika Hapuarachchi in producing, what he calls, the most comprehensive book ever written on Sinharaja.

“This will be the first major publication on Sinharaja since the early 1980s,” he said.

“It covers ecology, history, flora, fauna—and includes rare photographs taken over nearly 30 years.”

Some images were captured after weeks of waiting. Others after years—like the mysterious mass-flowering episodes where clusters of forest giants bloom in synchrony, or the delicate jewels of the understory: tiny jumping spiders, elusive amphibians, and canopy dwellers glimpsed only once in a lifetime.

The book even includes underwater photography from Sinharaja’s crystal-clear streams—worlds unseen by most visitors.

A Tribute to a Departed Friend

Halfway through the project, tragedy struck: co-author Dr. Janaka Gallangoda passed away.

“We stopped the project for a while,” Weeratunga said quietly.

“But Dr. Thilak Jayaratne reminded us that Janaka lived for this forest. So we completed the book in his memory. One of our authors now watches over Sinharaja from above.”

An Invitation to the Public

A special exhibition, showcasing highlights from the book, will be held on 13–14 December, 2025, in Colombo.

“We cannot show Sinharaja in one gallery,” he laughed.

“But we can show a single drop of its beauty—enough to spark curiosity.”

A Forest That Must Endure

What makes the book special, he emphasises, is its accessibility.

“We wrote it in simple, clear language—no heavy jargon—so that everyone can understand why Sinharaja is irreplaceable,” Weeratunga said.

“If people know its value, they will protect it.”

To him, Sinharaja is more than a rainforest.

It is Sri Lanka’s living heritage.

A sanctuary of evolution.

A sacred, breathing cathedral that must endure for generations to come.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

How Knuckles was sold out

Leaked RTI Files Reveal Conflicting Approvals, Missing Assessments, and Silent Officials

“This Was Not Mismanagement — It Was a Structured Failure”— CEJ’s Dilena Pathragoda

An investigation, backed by newly released Right to Information (RTI) files, exposes a troubling sequence of events in which multiple state agencies appear to have enabled — or quietly tolerated — unauthorised road construction inside the Knuckles Conservation Forest, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

At the centre of the unfolding scandal is a trail of contradictory letters, unexplained delays, unsigned inspection reports, and sudden reversals by key government offices.

“What these documents show is not confusion or oversight. It is a structured failure,” said Dilena Pathragoda, Executive Director of the Centre for Environmental Justice (CEJ), who has been analysing the leaked records.

“Officials knew the legal requirements. They ignored them. They knew the ecological risks. They dismissed them. The evidence points to a deliberate weakening of safeguards meant to protect one of Sri Lanka’s most fragile ecosystems.”

A Paper Trail of Contradictions

RTI disclosures obtained by activists reveal:

Approvals issued before mandatory field inspections were carried out

Three departments claiming they “did not authorise” the same section of the road

A suspiciously backdated letter clearing a segment already under construction

Internal memos flagging “missing evaluation data” that were never addressed

“No-objection” notes do not hold any legal weight for work inside protected areas, experts say.

One senior officer’s signature appears on two letters with opposing conclusions, sent just three weeks apart — a discrepancy that has raised serious questions within the conservation community.

“This is the kind of documentation that usually surfaces only after damage is done,” Pathragoda said. “It shows a chain of administrative behaviour designed to delay scrutiny until the bulldozers moved in.”

The Silence of the Agencies

Perhaps, more alarming is the behaviour of the regulatory bodies.

Multiple departments — including those legally mandated to halt unauthorised work — acknowledged concerns in internal exchanges but issued no public warnings, took no enforcement action, and allowed machinery to continue operating.

“That silence is the real red flag,” Pathragoda noted.

“Silence is rarely accidental in cases like this. Silence protects someone.”

On the Ground: Damage Already Visible

Independent field teams report:

Fresh erosion scars on steep slopes

Sediment-laden water in downstream streams

Disturbed buffer zones

Workers claiming that they were instructed to “complete the section quickly”

Satellite images from the past two months show accelerated clearing around the contested route.

Environmental experts warn that once the hydrology of the Knuckles slopes is altered, the consequences could be irreversible.

CEJ: “Name Every Official Involved”

CEJ is preparing a formal complaint demanding a multi-agency investigation.

Pathragoda insists that responsibility must be traced along the entire chain — from field officers to approving authorities.

“Every signature, every omission, every backdated approval must be examined,” she said.

“If laws were violated, then prosecutions must follow. Not warnings. Not transfers. Prosecutions.”

A Scandal Still Unfolding

More RTI documents are expected to come out next week, including internal audits and communication logs that could deepen the crisis for several agencies.

As the paper trail widens, one thing is increasingly clear: what happened in Knuckles is not an isolated act — it is an institutional failure, executed quietly, and revealed only because citizens insisted on answers.

by Ifham Nizam

-

News6 days ago

Lunuwila tragedy not caused by those videoing Bell 212: SLAF

-

News19 hours ago

News19 hours agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLevel III landslide early warning continue to be in force in the districts of Kandy, Kegalle, Kurunegala and Matale

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoDitwah: An unusual cyclone

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoLOLC Finance Factoring powers business growth

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoCPC delegation meets JVP for talks on disaster response

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoA 6th Year Accolade: The Eternal Opulence of My Fair Lady

-

News19 hours ago

News19 hours agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale