Sat Mag

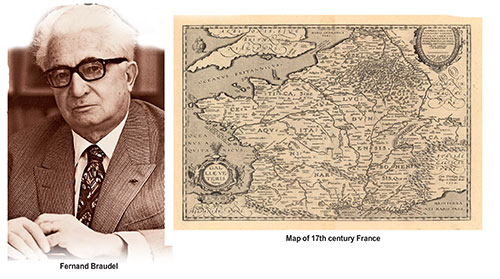

The last frontier: Fernand Braudel’s France

By Uditha Devapriya

Fernand Braudel’s “The Identity of France, Volume I: History and Environment”, translated by Siân Reynolds. HarperPerennial, 432 pp., 1993.

Since at least Jason and Odysseus, home has rarely been where the heart is. The Greek hero leaves everyone dear to him, in pursuit of a divine calling. In all those myths that immortalise him, his catharsis comes once he realises that home is more than just a geographic space: that it’s part of a cosmos spanning heaven and earth, between which he must serve as messenger and mediator. Contemporary intellectuals are no different: postmodern Odysseuses in their own right, they too traverse multiple worlds and mediate between them.

Multiple worlds, of course, don’t exist between multiple geographical spaces: they can be, as they often are, the same space, the tides of change sweeping across them through the years. In the first of his two colossal books on France (The Identity of France, originally planned for four volumes) Fernand Braudel transforms from historian to cartographer, taking us through village after bourg after city, as these tides of change sweep over, turning them not only from village to city, but also, occasionally, from city back to village.

From the 13th to the 18th century, these communities – and Braudel dwells on four of them, Besançon, Roanne, Laval, and Caen, before moving on to Paris – evolved at different speeds and on different levels, either gobbling up neighbouring spaces or being gobbled up by other spaces in turn. France’s cities grew as fast as neighbouring towns allowed them to, and as quickly as their roads connected them to bigger cities. Depending on whether these roads were wide enough, the linkages between towns would tighten or snap.

Thus the moment merchants and traders discovered quicker routes to Paris, the undisputed capital even then, one town’s prospects would improve at another’s cost. Indeed the fortunes of these cities depended more than anyone else on the whims of traders. Where they went, the cities they set camp in prospered; where they left, they sank.

Thus the moment merchants and traders discovered quicker routes to Paris, the undisputed capital even then, one town’s prospects would improve at another’s cost. Indeed the fortunes of these cities depended more than anyone else on the whims of traders. Where they went, the cities they set camp in prospered; where they left, they sank.

This is how Besançon profited from the arrival of Genoese bankers and merchants in the 16th century. Having been expelled from Lyon by Frances I (a Spanish colony then, Besançon was still to be conquered by Louis XIV following his marriage to Marie-Thérèse), these financiers found the city’s proximity to their former “home” (again, a fluid term, especially for as fluid a vocation as a banker’s or a merchant’s) much too an advantage to let go. One by one, some of the century’s most powerful financiers made their way here, soon to be followed by richer immigrants from Montpellier, Lons-le-Saunier, Luxeuil, and Fontenoy-en-Voge.

Yet a mere century’s passing reversed these fortunes, reducing it to a hotbed of poverty. On May 15, 1674, against the onslaught of some 200,000 cannon balls, it finally surrendered to French conquest. Such twists of fate overwhelmed cities elsewhere too.

The quicker these towns evolved, grew, prospered, even languished, the quicker became their incorporation and integration into the wider French polity. Yet this abstraction of France as a single unit never came to fruition until the monarchy itself had run its course: nationalism in its modern form, after all, dates from the Revolution of 1789. With villages squeezed beyond the limits of endurance, with tax upon tax forcing the peasant to finance France’s wars abroad and Louis XVI’s hubris at home, the bourgeoisie, incorporated by conquest to the monarchy, took part in the uprising against the Empire, replacing the landed aristocracy with a capitalist State. Thus nationalism, the political expression of the bourgeoisie, articulated itself here, as elsewhere, in the voice of a unified civic consciousness.

Braudel shows us how even this unified civic consciousness failed to dampen or put a stopper on the consciousness of towns and villages. What historians call “provincial particularism” – a term that evokes the particularism which prevailed in the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa periods here – sometimes if not often prevailed over the consolidation of unitary nationalism. To what extent did this fragmentation of France – “France’s name is diversity,” wrote Lucien Febvre – into different regional polities reflect the autonomy of those polities? Braudel does not provide all the answers, but like all good historians – and what better example of such an intellectual do we have than him? – he gives us real life, tangible case studies.

How one makes sense of a country thrice Britain’s size and twice Germany’s invariably boils down to what united it and divided it. Eric Wolf begins and ends his Europe and the People Without History with the point that time compresses space, as one mode of production gives way to another, and one tribe or clan surrenders to another. Yet despite this compression, one could say atomisation, of space, remnants of the past – cultural, linguistic, social, economic, even political – remain. Faced with the threat of their obliteration, civilisations respond in two ways: they fight back, or they adapt. In the case of France, Braudel is unequivocal: most of the time its constituent parts fought back, yet often they adapted.

The maze of dialects, accents, languages, not to mention cultural mores, even units of measurement (“Is it possible to lay down a single standard capacity for the cask of wine?”one intendant of Poitou was asked in 1684), makes it hard if not impossible for one to put a finger on the country, indeed on the very idea of it. Where does one begin?

very town, Braudel informs us, had a different social equation within a separate economy: in Mountauban it was the clothiers who reigned supreme, in Toulouse it was the landowner, and in Dunkirk those who owned and handled ships. The bourgeoisie took time to emerge in these enclaves of nascent capitalism, but their ancestors were there, trading, bartering, often speculating, rebelling against the intendants and the tax-officers.

On these different social equations rested different, at times unidentifiable, patterns of life, and on them rested a fundamental division between north and south. Thus provincialism in France, as in Britain, reflected a duality: two territories encompassing hundreds of villages, towns, and bourgs between them. This duality, Braudel tells us, was mostly linguistic, lying on either side of the frontier from La Réole to the basin of the Var River.

To which side you belonged depended, incredibly, on how you answered in the affirmative: in the north everyone replied with oui, in the south with oc. Oui eventually came to prevail over oc, no doubt because the north produced the culture, the politics, indeed the very mores, which constituted the idea of France. Yet these linguistic divisions remained; more than one famous chronicler from the north made his way through the south without understanding a word of what he heard: “I swear to you,” wrote a frustrated Racine to his friend La Fontaine in 1661, “that I need an interpreter here as much as a Muscovite would need in Paris.” Such differences in language were punctuated by even sharper contrasts of dialect, often within the same area: thus on either side of the Garonne, people spoke “two completely different patois” of Gascon, itself spoken in two provinces, Gascony and Guyenne.

To which side you belonged depended, incredibly, on how you answered in the affirmative: in the north everyone replied with oui, in the south with oc. Oui eventually came to prevail over oc, no doubt because the north produced the culture, the politics, indeed the very mores, which constituted the idea of France. Yet these linguistic divisions remained; more than one famous chronicler from the north made his way through the south without understanding a word of what he heard: “I swear to you,” wrote a frustrated Racine to his friend La Fontaine in 1661, “that I need an interpreter here as much as a Muscovite would need in Paris.” Such differences in language were punctuated by even sharper contrasts of dialect, often within the same area: thus on either side of the Garonne, people spoke “two completely different patois” of Gascon, itself spoken in two provinces, Gascony and Guyenne.

Standing apart from these provinces, while connecting them together, was Paris: not the only big city in the country, but the biggest among them (from 1787 to 1789 its population stood at 524,186, an underestimate according to Braudel, but in itself four times as high as the next city on the list, Lyon: 138,684). Yet like France itself, Paris never incorporated itself as one, nor allowed itself to be incorporated into one. Occupational specialisation within its districts compounded ethnic stratifications, with Saint-Marcel housing poorer artisans and being overwhelmed by successive waves of immigration from Lorraine, Burgundy, Lorraine, and Champagne, and Saint-Jacques transforming into the preferred home of the Limousins. These quarters, as with most cities in Europe, turned into urban villages, “where people could recognise their own ‘pays’.” Such divisions did not fade away with capitalism’s rise: as late as the 1960s, certain Parisian streets remained meeting spots for certain communities.

Reading Braudel, one wonders whether Europe’s encounters with nationalism ever really succeeded in forging a sense of unity between its cities. The case appears to be particularly pronounced in France, in which the tiers of settlement followed, not a preconceived and predetermined course, but rather a wayward, haphazard trajectory, from the Rhone corridor to the Parisian basin. It both echoed and diverged from the experience of Western Europe, on account of two reasons: its size and population, and the peculiar character of its bourgeoisie. Indeed, the role played by the latter may have forced the State to regulate the convulsions of commerce by centralising its authority. The conclusion to be drawn there is that, in France, diversity coexisted with an irregular, but continuous, process of unification.

If there is one problem with this view of French history, it’s that it simplifies the reality of post-16th century economic, political, and cultural consolidation of French society. One must understand why the author engaged in such simplifications. In writing his account of French history, Braudel was reacting to contemporary historiography which charted France from the tail-end of the 19th century: a historiography tracing its origins to Hippolyte Taine and Alexis de Tocqueville – centring on the notion that “France was born of the dramatic ordeal to which it was subjected during the violence of the Revolution” – and questioned if not challenged by the Annales school to which Braudel belonged.

In reacting against those earlier “Scholars of the Republic” (as I like to call them), Braudel hence went back in time, poring over Michelet, Racine, and other “documentarians”, before moving on to Lucien Febvre. The line between Febvre and Michelet is unmistakeably clear there: the one “his [Braudel’s] immediate master”, as Perry Anderson described him, and the other, possibly, the master of that master. The France they saw was very different to, and in fact lay a world away from, the France Taine and de Tocqueville dwelt on. It was the France that Braudel lived through, wrote of, talked about, and ultimately died in.

The author intended, as I mentioned earlier in parentheses, to follow this volume (“History and Environment”) and its sequel (“People and Production”) with two more: on culture and on external relations. That would have been a fitting coda to his earlier works, priceless in their own right: his magisterial two volume study of the Mediterranean under Philip II, his trilogy on Civilization and Capitalism (still the best there is, translated as with The Identity of France by Siân Reynolds), and several others besides (including A History of Civilizations, a personal favourite and a bedside companion). His death in 1985, however, marked an end of an era in historical scholarship, and put a permanent halt on the enterprise.

Braudel is not without his faults; even his trilogy on capitalism gets several points wrong, including the entry on Ceylon tea. Yet of these faults one can say, they never really tarnished his perspective: what he called the longue durée. Though never an avowed Marxist, much less a practicing one, his preference for social history, as opposed to the series of dates and names and innumerable other associations one memorises today, put him on par with Marxist historiographers. The two volumes of The Identity of France have long been out of print – the copies I have are old and tattered – but they are available on second-hand bookstores online. They offer an insight into a great historian – though by no means an omnipotent all-seeing one – and hold the ideal to which those in his trade should aspire. And of course, they evoke the fluidity of home: neither limited to geography, nor stuck in posterity.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Sat Mag

October 13 at the Women’s T20 World Cup: Injury concerns for Australia ahead of blockbuster game vs India

Australia vs India

Sharjah, 6pm local time

Australia have major injury concerns heading into the crucial clash. Just four balls into the match against Pakistan, Tayla Vlaeminck was out with a right shoulder dislocation. To make things worse, captain Alyssa Healy suffered an acute right foot injury while batting on 37 as she hobbled off the field with Australia needing 14 runs to win. Both players went for scans on Saturday.

India captain Harmanpreet Kaur who had hurt her neck in the match against Pakistan, turned up with a pain-relief patch on the right side of her neck during the Sri Lanka match. She also didn’t take the field during the chase. Fast bowler Pooja Vastrakar bowled full-tilt before the Sri Lanka game but didn’t play.

India will want a big win against Australia. If they win by more than 61 runs, they will move ahead of Australia, thereby automatically qualifying for the semi-final. In a case where India win by fewer than 60 runs, they will hope New Zealand win by a very small margin against Pakistan on Monday. For instance, if India make 150 against Australia and win by exactly 10 runs, New Zealand need to beat Pakistan by 28 runs defending 150 to go ahead of India’s NRR. If India lose to Australia by more than 17 runs while chasing a target of 151, then New Zealand’s NRR will be ahead of India, even if Pakistan beat New Zealand by just 1 run while defending 150.

Overall, India have won just eight out of 34 T20Is they’ve played against Australia. Two of those wins came in the group-stage games of previous T20 World Cups, in 2018 and 2020.

Australia squad:

Alyssa Healy (capt & wk), Darcie Brown, Ashleigh Gardner, Kim Garth, Grace Harris, Alana King, Phoebe Litchfield, Tahlia McGrath, Sophie Molineux, Beth Mooney, Ellyse Perry, Megan Schutt, Annabel Sutherland, Tayla Vlaeminck, Georgia Wareham

India squad:

Harmanpreet Kaur (capt), Smriti Mandhana (vice-capt), Yastika Bhatia (wk), Shafali Verma, Deepti Sharma, Jemimah Rodrigues, Richa Ghosh (wk), Pooja Vastrakar, Arundhati Reddy, Renuka Singh, D Hemalatha, Asha Sobhana, Radha Yadav, Shreyanka Patil, S Sajana

Tournament form guide:

Australia have three wins in three matches and are coming into this contest having comprehensively beaten Pakistan. With that win, they also all but sealed a semi-final spot thanks to their net run rate of 2.786. India have two wins in three games. In their previous match, they posted the highest total of the tournament so far – 172 for 3 and in return bundled Sri Lanka out for 90 to post their biggest win by runs at the T20 World Cup.

Players to watch:

Two of their best batters finding their form bodes well for India heading into the big game. Harmanpreet and Mandhana’s collaborative effort against Pakistan boosted India’s NRR with the semi-final race heating up. Mandhana, after a cautious start to her innings, changed gears and took on Sri Lanka’s spinners to make 50 off 38 balls. Harmanpreet, continuing from where she’d left against Pakistan, played a classic, hitting eight fours and a six on her way to a 27-ball 52. It was just what India needed to reinvigorate their T20 World Cup campaign.

[Cricinfo]

Sat Mag

Living building challenge

By Eng. Thushara Dissanayake

The primitive man lived in caves to get shelter from the weather. With the progression of human civilization, people wanted more sophisticated buildings to fulfill many other needs and were able to accomplish them with the help of advanced technologies. Security, privacy, storage, and living with comfort are the common requirements people expect today from residential buildings. In addition, different types of buildings are designed and constructed as public, commercial, industrial, and even cultural or religious with many advanced features and facilities to suit different requirements.

We are facing many environmental challenges today. The most severe of those is global warming which results in many negative impacts, like floods, droughts, strong winds, heatwaves, and sea level rise due to the melting of glaciers. We are experiencing many of those in addition to some local issues like environmental pollution. According to estimates buildings account for nearly 40% of all greenhouse gas emissions. In light of these issues, we have two options; we change or wait till the change comes to us. Waiting till the change come to us means that we do not care about our environment and as a result we would have to face disastrous consequences. Then how can we change in terms of building construction?

Before the green concept and green building practices come into play majority of buildings in Sri Lanka were designed and constructed just focusing on their intended functional requirements. Hence, it was much likely that the whole process of design, construction, and operation could have gone against nature unless done following specific regulations that would minimize negative environmental effects.

We can no longer proceed with the way we design our buildings which consumes a huge amount of material and non-renewable energy. We are very concerned about the food we eat and the things we consume. But we are not worrying about what is a building made of. If buildings are to become a part of our environment we have to design, build and operate them based on the same principles that govern the natural world. Eventually, it is not about the existence of the buildings, it is about us. In other words, our buildings should be a part of our natural environment.

The living building challenge is a remarkable design philosophy developed by American architect Jason F. McLennan the founder of the International Living Future Institute (ILFI). The International Living Future Institute is an environmental NGO committed to catalyzing the transformation toward communities that are socially just, culturally rich, and ecologically restorative. Accordingly, a living building must meet seven strict requirements, rather certifications, which are called the seven “petals” of the living building. They are Place, Water, Energy, Equity, Materials, Beauty, and Health & Happiness. Presently there are about 390 projects around the world that are being implemented according to Living Building certification guidelines. Let us see what these seven petals are.

Place

This is mainly about using the location wisely. Ample space is allocated to grow food. The location is easily accessible for pedestrians and those who use bicycles. The building maintains a healthy relationship with nature. The objective is to move away from commercial developments to eco-friendly developments where people can interact with nature.

Water

It is recommended to use potable water wisely, and manage stormwater and drainage. Hence, all the water needs are captured from precipitation or within the same system, where grey and black waters are purified on-site and reused.

Energy

Living buildings are energy efficient and produce renewable energy. They operate in a pollution-free manner without carbon emissions. They rely only on solar energy or any other renewable energy and hence there will be no energy bills.

Equity

What if a building can adhere to social values like equity and inclusiveness benefiting a wider community? Yes indeed, living buildings serve that end as well. The property blocks neither fresh air nor sunlight to other adjacent properties. In addition, the building does not block any natural water path and emits nothing harmful to its neighbors. On the human scale, the equity petal recognizes that developments should foster an equitable community regardless of an individual’s background, age, class, race, gender, or sexual orientation.

Materials

Materials are used without harming their sustainability. They are non-toxic and waste is minimized during the construction process. The hazardous materials traditionally used in building components like asbestos, PVC, cadmium, lead, mercury, and many others are avoided. In general, the living buildings will not consist of materials that could negatively impact human or ecological health.

Beauty

Our physical environments are not that friendly to us and sometimes seem to be inhumane. In contrast, a living building is biophilic (inspired by nature) with aesthetical designs that beautify the surrounding neighborhood. The beauty of nature is used to motivate people to protect and care for our environment by connecting people and nature.

Health & Happiness

The building has a good indoor and outdoor connection. It promotes the occupants’ physical and psychological health while causing no harm to the health issues of its neighbors. It consists of inviting stairways and is equipped with operable windows that provide ample natural daylight and ventilation. Indoor air quality is maintained at a satisfactory level and kitchen, bathrooms, and janitorial areas are provided with exhaust systems. Further, mechanisms placed in entrances prevent any materials carried inside from shoes.

The Bullitt Center building

Bullitt Center located in the middle of Seattle in the USA, is renowned as the world’s greenest commercial building and the first office building to earn Living Building certification. It is a six-story building with an area of 50,000 square feet. The area existed as a forest before the city was built. Hence, the Bullitt Center building has been designed to mimic the functions of a forest.

The energy needs of the building are purely powered by the solar system on the rooftop. Even though Seattle is relatively a cloudy city the Bullitt Center has been able to produce more energy than it needed becoming one of the “net positive” solar energy buildings in the world. The important point is that if a building is energy efficient only the area of the roof is sufficient to generate solar power to meet its energy requirement.

It is equipped with an automated window system that is able to control the inside temperature according to external weather conditions. In addition, a geothermal heat exchange system is available as the source of heating and cooling for the building. Heat pumps convey heat stored in the ground to warm the building in the winter. Similarly, heat from the building is conveyed into the ground during the summer.

The potable water needs of the building are achieved by treating rainwater. The grey water produced from the building is treated and re-used to feed rooftop gardens on the third floor. The black water doesn’t need a sewer connection as it is treated to a desirable level and sent to a nearby wetland while human biosolid is diverted to a composting system. Further, nearly two third of the rainwater collected from the roof is fed into the groundwater and the process resembles the hydrologic function of a forest.

It is encouraging to see that most of our large-scale buildings are designed and constructed incorporating green building concepts, which are mainly based on environmental sustainability. The living building challenge can be considered an extension of the green building concept. Amanda Sturgeon, the former CEO of the ILFI, has this to say in this regard. “Before we start a project trying to cram in every sustainable solution, why not take a step outside and just ask the question; what would nature do”?

Sat Mag

Something of a revolution: The LSSP’s “Great Betrayal” in retrospect

By Uditha Devapriya

On June 7, 1964, the Central Committee of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party convened a special conference at which three resolutions were presented. The first, moved by N. M. Perera, called for a coalition with the SLFP, inclusive of any ministerial portfolios. The second, led by the likes of Colvin R. de Silva, Leslie Goonewardena, and Bernard Soysa, advocated a line of critical support for the SLFP, but without entering into a coalition. The third, supported by the likes of Edmund Samarakkody and Bala Tampoe, rejected any form of compromise with the SLFP and argued that the LSSP should remain an independent party.

The conference was held a year after three parties – the LSSP, the Communist Party, and Philip Gunawardena’s Mahajana Eksath Peramuna – had founded a United Left Front. The ULF’s formation came in the wake of a spate of strikes against the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government. The previous year, the Ceylon Transport Board had waged a 17-day strike, and the harbour unions a 60-day strike. In 1963 a group of working-class organisations, calling itself the Joint Committee of Trade Unions, began mobilising itself. It soon came up with a common programme, and presented a list of 21 radical demands.

In response to these demands, Bandaranaike eventually supported a coalition arrangement with the left. In this she was opposed, not merely by the right-wing of her party, led by C. P. de Silva, but also those in left parties opposed to such an agreement, including Bala Tampoe and Edmund Samarakkody. Until then these parties had never seen the SLFP as a force to reckon with: Leslie Goonewardena, for instance, had characterised it as “a Centre Party with a programme of moderate reforms”, while Colvin R. de Silva had described it as “capitalist”, no different to the UNP and by default as bourgeois as the latter.

The LSSP’s decision to partner with the government had a great deal to do with its changing opinions about the SLFP. This, in turn, was influenced by developments abroad. In 1944, the Fourth International, which the LSSP had affiliated itself with in 1940 following its split with the Stalinist faction, appointed Michel Pablo as its International Secretary. After the end of the war, Pablo oversaw a shift in the Fourth International’s attitude to the Soviet states in Eastern Europe. More controversially, he began advocating a strategy of cooperation with mass organisations, regardless of their working-class or radical credentials.

Pablo argued that from an objective perspective, tensions between the US and the Soviet Union would lead to a “global civil war”, in which the Soviet Union would serve as a midwife for world socialist revolution. In such a situation the Fourth International would have to take sides. Here he advocated a strategy of entryism vis-à-vis Stalinist parties: since the conflict was between Stalinist and capitalist regimes, he reasoned, it made sense to see the former as allies. Such a strategy would, in his opinion, lead to “integration” into a mass movement, enabling the latter to rise to the level of a revolutionary movement.

Though controversial, Pablo’s line is best seen in the context of his times. The resurgence of capitalism after the war, and the boom in commodity prices, had a profound impact on the course of socialist politics in the Third World. The stunted nature of the bourgeoisie in these societies had forced left parties to look for alternatives. For a while, Trotsky had been their guide: in colonial and semi-colonial societies, he had noted, only the working class could be expected to see through a revolution. This entailed the establishment of workers’ states, but only those arising from a proletarian revolution: a proposition which, logically, excluded any compromise with non-radical “alternatives” to the bourgeoisie.

To be sure, the Pabloites did not waver in their support for workers’ states. However, they questioned whether such states could arise only from a proletarian revolution. For obvious reasons, their reasoning had great relevance for Trotskyite parties in the Third World. The LSSP’s response to them showed this well: while rejecting any alliance with Stalinist parties, the LSSP sympathised with the Pabloites’ advocacy of entryism, which involved a strategic orientation towards “reformist politics.” For the world’s oldest Trotskyite party, then going through a series of convulsions, ruptures, and splits, the prospect of entering the reformist path without abandoning its radical roots proved to be welcoming.

Writing in the left-wing journal Community in 1962, Hector Abhayavardhana noted some of the key concerns that the party had tried to resolve upon its formation. Abhayavardhana traced the LSSP’s origins to three developments: international communism, the freedom struggle in India, and local imperatives. The latter had dictated the LSSP’s manifesto in 1936, which included such demands as free school books and the use of Sinhala and Tamil in the law courts. Abhayavardhana suggested, correctly, that once these imperatives changed, so would the party’s focus, though within a revolutionary framework. These changes would be contingent on two important factors: the establishment of universal franchise in 1931, and the transfer of power to the local bourgeoisie in 1948.

Paradoxical as it may seem, the LSSP had entered the arena of radical politics through the ballot box. While leading the struggle outside parliament, it waged a struggle inside it also. This dual strategy collapsed when the colonial government proscribed the party and the D. S. Senanayake government disenfranchised plantation Tamils. Suffering two defeats in a row, the LSSP was forced to think of alternatives. That meant rethinking categories such as class, and grounding them in the concrete realities of the country.

This was more or less informed by the irrelevance of classical and orthodox Marxian analysis to the situation in Sri Lanka, specifically to its rural society: with a “vast amorphous mass of village inhabitants”, Abhayavardhana observed, there was no real basis in the country for a struggle “between rich owners and the rural poor.” To complicate matters further, reforms like the franchise and free education, which had aimed at the emancipation of the poor, had in fact driven them away from “revolutionary inclinations.” The result was the flowering of a powerful rural middle-class, which the LSSP, to its discomfort, found it could not mobilise as much as it had the urban workers and plantation Tamils.

Where else could the left turn to? The obvious answer was the rural peasantry. But the rural peasantry was in itself incapable of revolution, as Hector Abhayavardhana has noted only too clearly. While opposing the UNP’s Westernised veneer, it did not necessarily oppose the UNP’s overtures to Sinhalese nationalism. As historians like K. M. de Silva have observed, the leaders of the UNP did not see their Westernised ethos as an impediment to obtaining support from the rural masses. That, in part at least, was what motivated the Senanayake government to deprive Indian estate workers of their most fundamental rights, despite the existence of pro-minority legal safeguards in the Soulbury Constitution.

To say this is not to overlook the unique character of the Sri Lankan rural peasantry and petty bourgeoisie. Orthodox Marxists, not unjustifiably, characterise the latter as socially and politically conservative, tilting more often than not to the right. In Sri Lanka, this has frequently been the case: they voted for the UNP in 1948 and 1952, and voted en masse against the SLFP in 1977. Yet during these years they also tilted to the left, if not the centre-left: it was the petty bourgeoisie, after all, which rallied around the SLFP, and supported its more important reforms, such as the nationalisation of transport services.

One must, of course, be wary of pasting the radical tag on these measures and the classes that ostensibly stood for them. But if the Trotskyite critique of the bourgeoisie – that they were incapable of reform, even less revolution – holds valid, which it does, then the left in the former colonies of the Third World had no alternative but to look elsewhere and to be, as Abhayavardhana noted, “practical men” with regard to electoral politics. The limits within which they had to work in Sri Lanka meant that, in the face of changing dynamics, especially among the country’s middle-classes, they had to change their tactics too.

Meanwhile, in 1953, the Trotskyite critique of Pabloism culminated with the publication of an Open Letter by James Cannon, of the US Socialist Workers’ Party. Cannon criticised the Pabloite line, arguing that it advocated a policy of “complete submission.” The publication of the letter led to the withdrawal of the International Committee of the Fourth International from the International Secretariat. The latter, led by Pablo, continued to influence socialist parties in the Third World, advocating temporary alliances with petty bourgeois and centrist formations in the guise of opposing capitalist governments.

For the LSSP, this was a much-needed opening. Even as late as 1954, three years after S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike formed the SLFP, the LSSP continued to characterise the latter as the alternative bourgeois party in Ceylon. Yet this did not deter it from striking up no contest pacts with Bandaranaike at the 1956 election, a strategy that went back to November 1951, when the party requested the SLFP to hold a discussion about the possibility of eliminating contests in the following year’s elections. Though it extended critical support to the MEP government in 1956, the LSSP opposed the latter once it enacted emergency measures in 1957, mobilising trade union action for a period of three years.

At the 1960 election the LSSP contested separately, with the slogan “N. M. for P.M.” Though Sinhala nationalism no longer held sway as it had in 1956, the LSSP found itself reduced to a paltry 10 seats. It was against this backdrop that it began rethinking its strategy vis-à-vis the ruling party. At the throne speech in April 1960, Perera openly declared that his party would not stabilise the SLFP. But a month later, in May, he called a special conference, where he moved a resolution for a coalition with the party. As T. Perera has noted in his biography of Edmund Samarakkody, the response to the resolution unearthed two tendencies within the oppositionist camp: the “hardliners” who opposed any compromise with the SLFP, including Samarakkody, and the “waverers”, including Leslie Goonewardena.

These tendencies expressed themselves more clearly at the 1964 conference. While the first resolution by Perera called for a complete coalition, inclusive of Ministries, and the second rejected a coalition while extending critical support, the third rejected both tactics. The outcome of the conference showed which way these tendencies had blown since they first manifested four years earlier: Perera’s resolution obtained more than 500 votes, the second 75 votes, the third 25. What the anti-coalitionists saw as the “Great Betrayal” of the LSSP began here: in a volte-face from its earlier position, the LSSP now held the SLFP as a party of a radical petty bourgeoisie, capable of reform.

History has not been kind to the LSSP’s decision. From 1970 to 1977, a period of less than a decade, these strategies enabled it, as well as the Communist Party, to obtain a number of Ministries, as partners of a petty bourgeois establishment. This arrangement collapsed the moment the SLFP turned to the right and expelled the left from its ranks in 1975, in a move which culminated with the SLFP’s own dissolution two years later.

As the likes of Samarakkody and Meryl Fernando have noted, the SLFP needed the LSSP and Communist Party, rather than the other way around. In the face of mass protests and strikes in 1962, the SLFP had been on the verge of complete collapse. The anti-coalitionists in the LSSP, having established themselves as the LSSP-R, contended later on that the LSSP could have made use of this opportunity to topple the government.

Whether or not the LSSP could have done this, one can’t really tell. However, regardless of what the LSSP chose to do, it must be pointed out that these decades saw the formation of several regimes in the Third World which posed as alternatives to Stalinism and capitalism. Moreover, the LSSP’s decision enabled it to see through certain important reforms. These included Workers’ Councils. Critics of these measures can point out, as they have, that they could have been implemented by any other regime. But they weren’t. And therein lies the rub: for all its failings, and for a brief period at least, the LSSP-CP-SLFP coalition which won elections in 1970 saw through something of a revolution in the country.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist based in Sri Lanka who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoStandard Chartered appoints Harini Jayaweera as Chief Compliance Officer

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoWickremesinghe defends former presidents’ privileges

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoFifteen heads of Sri Lanka missions overseas urgently recalled

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoFive-star hotels stop serving pork products

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoWaiting for a Democratic Opposition

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoITAK denies secret pact with NPP

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoSri Lanka’s path to Lord’s

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoMilo powered Schools Netball finals from November 4