Life style

Amphibians going extinct in SL at a record pace

by Ifham Nizam

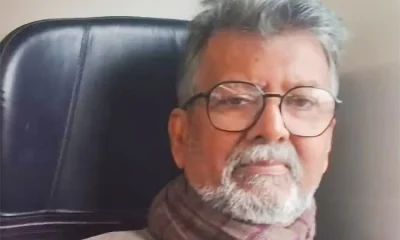

Sri Lanka holds the record for nearly 14 per cent of the amphibian extinctions in the world. In other words, of the 130 amphibian extinctions known to have occurred across the globe, 18 extinctions (14 per cent) have occurred in Sri Lanka, says Dr. Anslem de Silva, widely regarded as the father of Herpetology in the country. Speaking to The Sunday Island, the authors of a news book on amphibians, said that this is one of the highest number of amphibian extinctions known from a single country. Some consider this unusual extinction rate to be largely the result of the loss of nearly 70 per cent of the island’s forest cover. Dr. Anslem de Silva, Co-Chairman, Amphibian Specialist Group, International Union for the Conservation of Nature/Species Survival Commission (IUCN/SSC), together with two academics, Dr. Kanishka Ukuwela, Senior Lecture at Rajarata University, Mihintale who is  also associated with IUCN/SSC and Dr. Dillan Chaturanga, Lecture at Ruhuna University, Matara had authored this most comprehensive book on amphibians running to nearly 250 pages released last week. The prevalent levels of application of agrochemicals up to few months back, especially in rice fields, and vegetable and tea plantations, have increased over the past three decades. Similarly, the release of untreated industrial wastewater to natural water bodies has intensified. As a consequence, many streams and canals have become highly polluted, they say. The use of pesticides directly decreases the insect population, an important source of food for amphibians. Furthermore, these pollutants can easily make the water in paddy fields and the insects on which the amphibians feed toxic or increase the nitrogen content of the water. The highly permeable skins of amphibians would certainly cause them to be directly affected by these, they add. Amphibian mortality due to road traffic is a widespread problem globally that has been known to be responsible for population reductions and even local extinction in certaininstances. In Sri Lanka, amphibian mortalities due to road traffic are highly prevalent on roads that serve paddy fields, wetlands and forests. Further, they are especially intensified on rainy days when amphibian activity is high, the book explains. Recent studies indicate that amphibian road kills are exacerbated in certain national parks in the country due to increased visitation. According to recent estimates, several thousand amphibians are killed annually due to road traffic.

also associated with IUCN/SSC and Dr. Dillan Chaturanga, Lecture at Ruhuna University, Matara had authored this most comprehensive book on amphibians running to nearly 250 pages released last week. The prevalent levels of application of agrochemicals up to few months back, especially in rice fields, and vegetable and tea plantations, have increased over the past three decades. Similarly, the release of untreated industrial wastewater to natural water bodies has intensified. As a consequence, many streams and canals have become highly polluted, they say. The use of pesticides directly decreases the insect population, an important source of food for amphibians. Furthermore, these pollutants can easily make the water in paddy fields and the insects on which the amphibians feed toxic or increase the nitrogen content of the water. The highly permeable skins of amphibians would certainly cause them to be directly affected by these, they add. Amphibian mortality due to road traffic is a widespread problem globally that has been known to be responsible for population reductions and even local extinction in certaininstances. In Sri Lanka, amphibian mortalities due to road traffic are highly prevalent on roads that serve paddy fields, wetlands and forests. Further, they are especially intensified on rainy days when amphibian activity is high, the book explains. Recent studies indicate that amphibian road kills are exacerbated in certain national parks in the country due to increased visitation. According to recent estimates, several thousand amphibians are killed annually due to road traffic.

Professor W. A. Priyanka, PhD (USA), Professor in Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Peradeniya says the need for a guide to the amphibian fauna of Sri Lanka is obvious, given the currently critical conditions endangering them. Amphibians are an attractive group of animals whose diversity has always sparked interest among the scientific community, creating a vast body of unanswered questions.However, the identification of amphibians has been a challenge due to the lack of a complete and informative guide. The comprehensive pictorial guide provided by the new book should thus be of great benefit to a better understanding of the unique and intriguing nature of these fascinating living beings.The authors have done an outstanding job in compiling this book. An introduction to the guide briefly describes the history, current status, threats and conservation information, along with interesting folklore associated with amphibians. With the clear and informative images, distribution maps and updated status of each species, this guide can easily be comprehended by experts and beginners in the field alike.”I firmly believe that this book will be very useful to undergraduate and postgraduate students in the fields of zoology, biology and environmental science, as well as researchers, wildlife managers and visitors,” Professor Priyanka added.The authors said that like their previous guide to the reptiles of Sri Lanka, A Naturalist’s Guide to the Reptiles of Sri Lanka (de Silva & Ukuwela, 2017, 2020), this book is intended for both naturalists and visitors to Sri Lanka, providing an introduction to the amphibians found here. It features all the extant species of amphibian in this country with colour photographs and quick and easy tips for identification. At the time of writing, 120 species have been recorded within the country and ongoing taxonomic work is certain to add more to this impressive list in the next few years.This guide provides a general introduction to the amphibians of Sri Lanka, a profile of the physiographic, climatic, and vegetation features of the island, key characteristics that can be used in the identification of amphibians and descriptions of each extant amphibian species.Additionally, it presents information on amphibian conservation here and a brief introduction to folklore and traditional treatment methods for combating poisoning due to amphibians in this country. The species descriptions are arranged under their higher taxonomic groups(orders and families), and further grouped in their respective genera.The descriptions are organized in alphabetical order by their scientific names. Every species covered is accompanied by one or more colour photograph of the animal. Each account includes the vernacular name in English, the current scientific name, the vernacular name in Sinhala, a brief history of the species, a description with identification features, and details of habitat, habits and distribution (both here and outside the country).Key external identification features of the species, such as body form, skin texture and coloration, are provided, to help in the quick identification of an animal in the field.It must be noted that according to Sri Lanka’s wildlife laws, amphibians cannot be captured or removed from their natural habitats without official permits, which must be obtained in advance from the Department of Wildlife Conservation.Sri Lanka is home to an exceptional diversity of amphibians. Currently, the island nation boasts of 112 species of amphibians of which 98 are restricted to the country. However, nearly 60 per cent of this magnificent diversity is threatened with extinction. To make matters worse, very little attention is paid by the conservation authorities or the public. The last treatise on the subject was published 15 years ago. However, many changes have taken place since then and hence an updated compilation was a major necessity. This book by the three authors intends to popularize the study of amphibians by the general public by filling this large void. Historical aspects

Sri Lanka is one of the few countries in the world where conservation and protection of its fauna and flora has been practiced since pre-Christian times. There is much archaeological, historical and literary evidence to show that from ancient times amphibians have attracted the attention of the people of this island.

This is evident by the discovery of an ancient bronze cast of a frog (see photo) discovered during excavations conducted by the Department of Archaeology and the Central Cultural Fund. Strati-graphic evidence from the excavation sites indicate that these objects belong to the sixth to eighth centuries AD (Anuradhapura and Jetavanārāma museum records). Beliefs that feature the ‘good’ qualities of frogs and association with nature. These beliefs have some positive effects on the conservation of amphibians, perhaps one reason that Sri Lanka harbours a diverse assemblage of frogs. Absence of frogs and toads in agricultural fields indicates impending crop failure, it is believed.

The authors have specially thanked Managing Director John Beaufoy of John Beaufoy Publishing Ltd, for publishing many books promoting Sri Lanka diversity.

Life style

Celebration of taste, culture and elegance

Italian Cuisine Week

This year’s edition of Italian Cuisine Week in Sri Lanka unfolded with unmistakable charm, elegance and flavour as the Italian Embassy introduced a theme that captured the very soul of Italian social life ‘Apertivo and’ Stuzzichini’ This year’s celebration brought together diplomats, food lovers, chefs and Colombo’s society crowd for an evening filled with authenticity, refinement and the unmistakable charm of Italian hospitality.

Hosted at the Italian ambassador’s Residence in Colombo, the evening brought Italy’s golden hour ritual to life, embracing the warmth of Mediterranean hospitality and sophistication of Colombo social scene.

The ambience at the residence of the Italian Ambassador, effortlessly refined, evoked the timeless elegance of Milanese evening culture where ‘Apertivo’ is not just a drink , but a moment of pause, connection and pleasure. Guests were greeted with the aromas of apertivo classics and artisanal stuzzichini,curated specially for this edition. From rustic regional flavours to contemporary interpretations the embassy ‘s tables paid homage to Italy’s diverse culinary landscape.

, Italy’s small bites meant to tempt the palate before meal. Visiting Italian chefs worked alongside Colombo’s leading culinary teams to curate a menu that showcased regional authenticity though elegant bite sized creations. The Italian Ambassador of Italy in Sri Damiano Francovigh welcomed guests with heartfelt remarks on the significant of the theme, highlighting how “Apertivo”embodies the essence of Italy’s culinary identity, simple, social and rooted in tradition.

Sri Lanka’s participation in Italian Cuisine Week for ten consecutive years stands as a testament to the friendship between the two countries. This year focus on ‘Apertivo’ and ‘Stuzzichini’ added a fresh, dimension to that relationship, one that emphasised not only flavours, but shaped cultural values of hospitality, family and warmth. This year’s ‘Apertivo’ and “Stuzzichini’ theme brought a refreshing twist to Italian Cuisine Week. It reminded Sri Lankan guests t hat sometimes the most memorable culinary experiences come not from elaborate feasts but from the simplicity of serving small plates with good company.

Italian Cuisine Week 2025 in Sri Lanka may have showcased flavours, but more importantly it showcased connection and in the warm glow of Colombo’s evening Apertivo came alive not just as an Italian tradition.

(Pix by Dharmasena Wellipitiya)

By Zanita Careem

The Week of Italian Cuisine in the World is one of the longest-running thematic reviews promoted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation. Founded in 2016 to carry forward the themes of Expo Milano 2015—quality, sustainability, food

safety, territory, biodiversity, identity, and education—the event annually showcases the excellence and global reach of Italy’s food and wine sector.

Since its inauguration, the Week has been celebrated with over 10,000 events in more than 100 countries, ranging from tastings, show cooking and masterclasses to seminars, conferences, exhibitions and business events, with a major inaugural event hosted annually in Rome at the Farnesina, the HQ of the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation.

The 10th edition of the Italian Cuisine Week in the World.

In 2025, the Italian Cuisine Week in the World reaches its tenth edition.

The theme chosen for this anniversary is “Italian cuisine between culture, health and innovation.”

This edition highlights Italian cuisine as a mosaic of knowledge and values, where each tile reflects a story about the relationship with food.

The initiatives of the 10th Edition aim to:

promote understanding of Italian cuisine, also in the context of its candidacy for UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage;

demonstrate how Italian cuisine represents a healthy, balanced, and sustainable food model, supporting the prevention of non-communicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes;

emphasize the innovation and research that characterize every stage of the Italian food chain, from production to processing, packaging, distribution, consumption, reuse, and recycling

The following leading hotels in Colombo Amari Colombo, Cinnamon Life, ITC Ratnadipa and The Kingsbury join in the celebration by hosting Italian chefs throughout the Week.

- Jesudas, chef Collavini,Travis Casather and Mahinda Wijeratne

- Barbara Troila and Italian Ambassador Damiano F rancovigh

- Janaka Fonseka and Rasika Fonseka

- Mayor Balthazar and Ambassador of Vietnam,Trinh Thi Tam

- Anika Williamson

- Alberto Arcidiacono and Amber Dhabalia

- Thrilakshi Gaveesha

- Dasantha Fonseka and Kumari Fonseka

Life style

Ethical beauty takes centre stage

The Body Shop marked a radiant new chapter in Sri Lanka with the opening of its boutique at One Galle Face Mall, an event that blended conscious beauty, festive sparkle and lifestyle elegance. British born and globally loved beauty brand celebrates ten successful years in Sri lanka with the launch of its new store at the One Galle Face Mall. The event carried an added touch of prestige as the British High Commissioner Andrew Patrick to Sri Lanka attended as the Guest of honour.

His participation elevated the event highlighting the brand’s global influence and underscored the strong UK- Sri Lanka connection behind the Body Shop’s global heritage and ethical values.

Celebrating ten years of the Brand’s presence in the country, the launch became a true milestone in Colombo’s evolving beauty landscape.

Also present were the Body Shop Sri Lanka Director, Kosala Rohana Wickramasinghe, Shriti malhotra, Executive chairperson,Quest Retail.The Body shop South Asia and Vishal Chaturvedi , Chief Revenue Officer-The Body South Asia The boutique showcased the brand’s

complete range from refreshing Tea Tree skin care to the iconic body butters to hair care essentials each product enhancing the Body Shop’s values of cruelty ,fair trade formulation, fair trade ingredients and environmentally mindful packaging.

The store opening also unveiled the much anticipated festive season collection.

With its elegant atmosphere, engaging product experiences and the distinguished present of the British High Commissioner, it was an evening that blended glamour with conscience With its fresh inviting space at Colombo’ premier mall, the Body Shop begins a a new decade of inspiring Sri Lankan consumers to choose greener beauty.

Life style

Ladies’ Night lights up Riyadh

The Cultural Forum of Sri Lanka in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia brought back Ladies’ Night 2025 on November 7 at the Holiday Inn Al Qasr Hotel. After a hiatus of thirteen years, Riyadh shimmered once again as Ladies’ Night returned – an elegant celebration revived under the chairperson Manel Gamage and her team. The chief guest for the occasion was Azmiya Ameer Ajwad, spouse of the Ambassador of Sri Lanka to K. S. A. There were other dignitaries too.

The Cultural Forum of Sri Lanka in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia brought back Ladies’ Night 2025 on November 7 at the Holiday Inn Al Qasr Hotel. After a hiatus of thirteen years, Riyadh shimmered once again as Ladies’ Night returned – an elegant celebration revived under the chairperson Manel Gamage and her team. The chief guest for the occasion was Azmiya Ameer Ajwad, spouse of the Ambassador of Sri Lanka to K. S. A. There were other dignitaries too.

The show stopper was Lisara Fernando finalist from the voice Sri Lankan Seasons, wowed the crowd with her stunning performances. The excitement continued with a lively beauty pageant, where Ilham Shamara Azhar was crowned the beauty queen of the night. Thanks to a thrilling raffle draw, many lucky guests walked away with fabulous prizes, courtesy of generous sponsors.

The evening unfolded with a sense of renewal, empowerment and refined glamour drawing together the women for a night that was both historic and beautifully intimate. From dazzling couture to modern abayas, from soft light installation to curated entertainment, the night carried the unmistakable energy.

Once a cherished annual tradition, Ladies’ Night had long held a special space in Riyadh’s cultural calendar. But due to Covid this event was not held until this year in November. This year it started with a bang. After years Ladies’ Night returned bringing with a burst of colour, confidence and long-awaited camaraderie.

It became a symbol of renewal. This year began with a vibrant surge of energy. The decor blended soft elegance with modern modernity cascading its warm ambient lighting and shimmering accents that turned the venue into a chic, feminine oasis, curated by Shamila Abusally, Praveen Jayasinghe and Hasani Weerarathne setting the perfect atmosphere while compères Rashmi Fernando and Gayan Wijeratne kept the energy high and kept the guests on their toes making the night feel intimate yet grand.

Conversations flowed as freely as laughter. Women from different backgrounds, nationalities and professions came together united by an unspoken bond of joy and renewal. Ladies’ Night reflected a broader narrative of change. Riyadh today is confidently evolving and culturally dynamic.

The event celebrated was honouring traditions while empowering international flair.

As the night drew to a close, there was a shared sense that this event was only the beginning. The applause, the smiles, the sparkles in the air, all hinted at an event that is set to redeem its annual place with renewed purpose in the future. Manel Gamage and her team’s Ladies’ Night in Riyadh became more than a social occasion. It became an emblem of elegance, and reflected a vibrant new chapter of Saudi Arabia’s capital.

Thanks to Nihal Gamage and Nirone Disanayake, too, Ladies’ night proved to be more than event,it was a triumphant celebration of community, culture and an unstoppable spirit of Sr Lankan women in Riyadh

In every smile shared every dance step taken and every moment owned unapologetically Sr Lankan women in Riyadh continue to show unstoppable. Ladies’ Night is simply the spotlight that will shine forever .This night proved to be more than an event, it was a triumphant celebration of community, culture and the unstoppable spirit of Sri Lankan women in Riyadh.

In every smile shared, every dance steps taken and every moment owned unapologetically Sri Lankan women in Riyadh continue to show that their spirit is unstoppable. Ladies’ Night was simply the spotlight and the night closed on a note of pride!

- Evening glamour

- Different backgrounds, one unforgettable evening

- Shamila lighting traditional oil lamp while chief guest Azmiya looks on

- Unity in diversity

- capturing the spirit of the evening

- Radiant smiles stole the spotlight

- Every nationality added its own colour and charm

- Elegance personified

- Crowning the beauty queen

- Chairperson Manel Gamage welcoming guests

- Captivating performances

- Royal moment of poise and power

- Elegance and style in every form

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoFinally, Mahinda Yapa sets the record straight

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoOver 35,000 drug offenders nabbed in 36 days

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoCyclone Ditwah leaves Sri Lanka’s biodiversity in ruins: Top scientist warns of unseen ecological disaster

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoThe Catastrophic Impact of Tropical Cyclone Ditwah on Sri Lanka:

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoRising water level in Malwathu Oya triggers alert in Thanthirimale

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoHandunnetti and Colonial Shackles of English in Sri Lanka

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCabinet approves establishment of two 50 MW wind power stations in Mullikulum, Mannar region

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoSri Lanka betting its tourism future on cold, hard numbers