Features

THE DRAMATIC END – Part 31

CONFESSIONS OF A GLOBAL GYPSY

By Dr. Chandana (Chandi) Jayawardena DPhil

President – Chandi J. Associates Inc. Consulting, Canada

Founder & Administrator – Global Hospitality Forum

chandij@sympatico.ca

A Surprise at the Union AGM

The hotel union of Coral Gardens was hoping to deal with the new Manager, Major Siri Samarakoon more effectively with input from their superiors. The annual general meeting (AGM) was expected to re-establish the strength of the union. A very important chief guest, Mr. Bala Tampoe (Comrade Bala) was attending, A notice came from the hotel union to Major ‘informing’ the management of the details related to their AGM. Major wrote in bold letters across the notice, “Approved by the Manager”, signed the notice and placed it on the union notice board himself.

After all the hype, Comrade Bala arrived at the hotel in an old car and was given a rousing welcome by his devoted followers. They covered him with fresh flower garlands and ceremonially ushered him from the entrance of the hotel to the employee dormitory area where the AGM was to be held. The union was ready for the magic to happen. I was in the office in my chef uniform listening to the loud cheers of the employees celebrating the visit by their hero Comrade Bala.

After all the hype, Comrade Bala arrived at the hotel in an old car and was given a rousing welcome by his devoted followers. They covered him with fresh flower garlands and ceremonially ushered him from the entrance of the hotel to the employee dormitory area where the AGM was to be held. The union was ready for the magic to happen. I was in the office in my chef uniform listening to the loud cheers of the employees celebrating the visit by their hero Comrade Bala.

I was thinking of what would happen after the AGM. At that time, Major appeared in the office dressed in a bright red shirt and a pair of jeans. I was surprised and asked him if he was going out somewhere. “Yes, of course, to the union AGM,” he said in an excited voice. When I asked him, “Are you invited to the AGM?” he said that, “As the Manager of the hotel I am their host and I certainly do not need any invitation to go anywhere in the hotel.” I was baffled, when he said, “Chandana, let’s go and have some fun with these bloody communists.”

Around 100 employees attending the AGM were shocked to see Major and I marching bravely towards their leader just before the meeting commenced. That was the first union meeting I had ever attended. I followed Major and sat right in the front row after shaking hands with Comrade Bala, who looked confused by our surprise appearance. At 4:00 pm sharp, at the exact time the AGM was supposed to commence, the Major went to the podium, took the microphone in his hand, checked the sound and addressed the gathering, uninvited.

The Major stated the importance of commencing such meetings promptly, as busy people like him do not like to waste time. He then compared himself to Karl Marx, Vladimir Lenin and Bala Tampoe, as all four were lawyers or legal scholars. After that, Major gave a lengthy and informative lecture to the union on how he admired Karl Marx’s theories and philosophies on economics and socialism. Then he compared communism in USSR, China and Cuba. He argued that unions must embrace concepts that benefit members rather than the concepts that boost the egos of their selfish leaders.

He ended his unsolicited lecture by saying that if anyone at the AGM needs to learn more about socialism, communism or unionism, to make an appointment to consult him. He wished the union all success and left before any questions were posed to him. “Chandana, let’s leave this AGM to do some productive work,” he said while marching away, proudly. Comrade Bala and his loyal followers looked totally baffled.

Russian Roulette – Fire or Promote?

Towards the end of the tourist season in 1977, we had two more managers on our team. Sabinus Fernando had just retired from the National Milk Board as the Personnel Manager. He was an expert in handling tough unions. Neville Fernando was a volunteer Lieutenant of the Army who was previously trained by Major. He looked after security. Although they were on the management team of four, Major designated Sabinus and Neville as General Supervisors I and II. I familiarized both in hotel operations.

One day, Major had a special management meeting with one agenda item – terminating the services of either the President (Edmond) or the Secretary (Kalansooriya) of the hotel union. “Let’s break the union by promoting one leader and sacking the other. Let’s decide which one gets sacked.” Major sought our input, with a sadistic laugh. As there were no clear grounds for dismissal, I voted against such action, but the other three managers agreed to fire the younger and more radical union leader – Kalansooriya. I felt that the whole voting process was choreographed by Major. “What happens to Butler Edmond?” I questioned. “Let’s promote him as the Restaurant Supervisor!” Major concluded.

Major delegated three members of his management team specific tasks to implement his strategy:

= Chandana – Training, developing and promoting Edmond with new uniforms, good increment and benefits.

= Sabinus – Building a special case file for Kalansooriya and continuously provoking him until he makes a major mistake. “Sabinus, if you can provoke Kalanasooriya in such a manner for you to get slapped on the face by him in public, that would be perfect!” Major suggested. He was not joking.

= Neville – Getting Security Guards to check Kalansooriya thoroughly every time he leaves work while further harassing him with frequent questioning.

The very next day, I promoted Edmond and issued general notices to all employees. Edmond was very pleased with his new title and impressive salary increase. He came to our office with a big smile to thank Major and myself. “Sir, should I wear a tie to work?” a highly motivated Edmond asked us. Major did not want to spend any more hotel money for buying ties. Therefore, he told me, “I say Chandana, I see that you have a big collection of ties. Just give this chap a couple of your old ties.” I did so immediately, without asking any questions.

After that even when Edmond was off duty, he travelled home wearing my old ties, as that was a status symbol in his village. Before issuing the letter of promotion to Edmond, Major told him, “Edmond, one thing you need to do before your promotion is confirmed. You must resign from the hotel union.” “No problem, Sir, I will do that now.” Edmond said.

Timely, but Unfair Action

By early April, 1977, on the last day of the tourist season, when the last European tour group left the hotel, the occupancy dropped down to single digits. Major terminated Kalansooriya’s service on that day, as the last tourist coach left the hotel. Major had drafted a long letter with many legal terms. He managed to get the letter of termination issued from the head office and signed by a member of the board. We were expecting a strike, and if that happened, Major was prepared to close the hotel for the off season of six months to focus on maintenance and upgrading projects.

The union delegates wanted to meet with the management to discuss what they termed as: “a revengeful and unfair dismissal”. During that emotional meeting, a few union delegates broke down in tears. Major looked very sorry and spoke softly, “My heart goes to Kalansooriya, but unfortunately my hands are tied as the letter was issued and signed by my superior – the Hotel Company Director from the head office.” The union delegates then asked. “Can’t you speak with the Director and try to convince him to give Kalansooriya a second chance?” Major responded, “Sure, I will ask that when the Director returns to Sri Lanka after his current two-month holiday in England.” That was the end of the story.

After a week, there was no more talk about Kalansooriya among employees. Although, now not a part of the union that he built and led over 10 years, Edmond appeared to be a popular supervisor. Major took a one-month vacation making me the Acting Manager, once again.

Meeting JR

One morning in May, 1977, the kitchen became busy with a last-minute order for a Sri Lankan lunch for 50 persons of a major political party. As the majority of cooks were on their annual leave during the off season, I did most of the cooking. When the group arrived, I realised that it was for then Leader of the Opposition and the Member of the Parliament for Colombo South, where I was registered to vote. The veteran politician, Mr. Junius Richard Jayewardene (JR) was campaigning hard to bring his United National Party (UNP) back to power and become the sixth and the oldest person to become the Prime Minister of Ceylon/Sri Lanka. At age 70, he appeared to have a lot of energy to do three rallies a day during a three month-long campaign.

When JR arrived at the hotel, his 50 close supporters expected him to have lunch with them in the restaurant, but he had a different idea. When I greeted JR on his arrival at the entrance of the hotel, he wanted to meet with the Hotel Manager. I told him that I was acting for the Manager who was on vacation. JR said, “I thought that you are the Chef.” “Yes, Sir. I am. Do you need anything apart from lunch?” I inquired.

JR wanted a room and all newspapers of the day. I knew that JR had given strict instructions to his followers to boycott all newspapers published by the Lake House Group which had been taken over by the government of Sirima Bandaranaike. Therefore, I quickly asked, “Except the Daily News and Dinamina?” “I need to read all news papers including those two prior to my next rally this afternoon.” He was very clear. I ushered him to his room and arranged for his lunch to be served there. Then, while I was leaving his room, JR requested, “Can you stay and chat with me?”

JR had a quick wash and sat for lunch by himself while glancing through the headlines of the Daily News. I kept standing for over an hour chatting with JR. He sounded optimistic of a landslide victory during the general election scheduled for July 21, 1977. As the voters of Ceylon/Sri Lanka gave the victory to the main opposition party at all five general elections held after 1952, it was not a difficult prediction. Overstaying their term by two additional years by the government of Sirima Bandaranaike, motivated the voters to opt for a change. As arguably the father of modern-day tourism, JR was happy that I was a graduate of the Ceylon Hotel School. He was also pleased that I was from Colombo South and his namesake.

In the midst of our chat about various topics, including tourism, sea erosion, supply chain challenges stemming from the closed economic policy, frustrations of the local population; JR asked me, “Didn’t we meet at Sirikotha (UNP head office) some years back?” I said, “Yes, soon after your party suffered a big loss at the general elections in 1970.”

As a young child, listening to my fathers’ interesting stories about his interactions with then Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, I became interested in politics. When my father asked me what job I’d to do, I made him laugh by saying that, “I want to be like Banda.” I then followed activities of charismatic political leaders of Ceylon and around the world. In fact, as a pre-teen, one of my key hobbies was maintaining an album of photographs and articles about various politicians such as JFK, Nehru, Mao, Nasser, Jomo Kenyatta, Castro, Che, SWRD and JR.

As a young child, listening to my fathers’ interesting stories about his interactions with then Prime Minister S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike, I became interested in politics. When my father asked me what job I’d to do, I made him laugh by saying that, “I want to be like Banda.” I then followed activities of charismatic political leaders of Ceylon and around the world. In fact, as a pre-teen, one of my key hobbies was maintaining an album of photographs and articles about various politicians such as JFK, Nehru, Mao, Nasser, Jomo Kenyatta, Castro, Che, SWRD and JR.

In the late 1960s, I also became a big fan of Pierre Trudeau. I was fascinated how he rapidly rose to the position of the Prime Minister of Canada only after a short two and half years as a member of the parliament. I was delighted when Pierre Trudeau visited Ceylon to open the Colombo airport re-built and expanded with generous funding from Canada. With hundreds of other school children, I stood in line under the hot sun along the Galle Road for hours holding a Canadian flag to cheer this charismatic leader.

Three people – my father, and two politically-active classmates of mine at Grade 11 (Imthiaz Bakeer Markar and Sarath Kongahage – both who became lawyers and leading politicians in later years) encouraged me to get involved in politics. When I was 16 years of age Imthiaz took me and a few other students of Ananda College to meet the newly elected leader of the UNP – JR, who wanted to recruit young members to his political party, which he was re-uilding then, with the assistance of R. Premadasa as his right-hand man.

“How come you did not join the UNP in 1970 and get into politics? You would have done well,” JR said. I told him that owing to undemocratic practices by all political parties in Sri Lanka, I lost interest in that career option. However, he was happy that I was focused on a long career in tourism and hospitality, which he believed would be the main industry in Sri Lanka in years to come.

After he finished his lunch JR thanked me and said that he will now rest. “At my age, I realised that I am more productive if I break my long days into two with a short cat nap in between” he said.

Hosting JR, Again

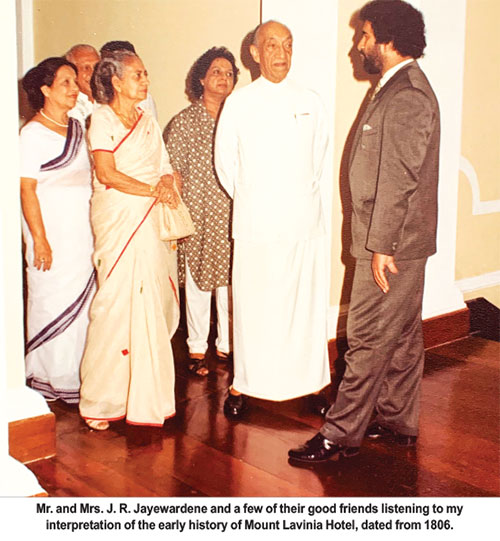

Over the next 12 years, I hosted JR a few times at hotel functions during his two terms as the first Executive President of Sri Lanka. My last meeting with JR was in 1993, when I conducted a quick tour of the upgraded historic wing of the Mount Lavinia Hotel at his request. By then he had retired from politics and I was planning to leave Sri Lanka to re-commence my international career.

During that last meeting JR told me how as a young man he and his buddies partied at the Little Hut Night Club of the Mount Lavinia Hotel. “Your Excellency, why don’t you bring all your good friends and have a night out at the Little Hut. Pick any day and I will make all arrangements including a live band to play all your favourite songs all night long” I offered. JR smiled, thought about it, looked at his wife, and then said, “Thank you very much. Let Elina and I think about it. The challenge is that most of my former buddies have now passed away.” He was 87 years of age then, but still had that quick wit. Mr. J. R. Jayewardene was the first of 35 heads of state or government I hosted during my career as an international hotelier.

Socialism Rejected

As predicted by JR the election results on July 21, 1977 was a landslide victory for the UNP, which won 140 of the 168 seats in the National State Assembly. Controlling over 83% of seats, JR was able to initiate several amendments to the constitution and become far more powerful than all his five predecessors of the independent Ceylon/Sri Lanka. The leftist parties which controlled the trade unions lost all 19 seats they had held previously. Major took great joy in announcing to his small management team that the era of the communist unions in Sri Lanka had just ended! “Let’s bring the number of members in the Coral Gardens Hotel union to zero within a month,” said Major expanding his new vision.

Features

Making ‘Sinhala Studies’ globally relevant

On 8 January 2026, I delivered a talk at an event at the University of Colombo marking the retirement of my longtime friend and former Professor of Sinhala, Ananda Tissa Kumara and his appointment as Emeritus Professor of Sinhala in that university. What I said has much to do with decolonising social sciences and humanities and the contributions countries like ours can make to the global discourses of knowledge in these broad disciplines. I have previously discussed these issues in this column, including in my essay, ‘Does Sri Lanka Contribute to the Global Intellectual Expansion of Social Sciences and Humanities?’ published on 29 October 2025 and ‘Can Asians Think? Towards Decolonising Social Sciences and Humanities’ published on 31 December 2025.

On 8 January 2026, I delivered a talk at an event at the University of Colombo marking the retirement of my longtime friend and former Professor of Sinhala, Ananda Tissa Kumara and his appointment as Emeritus Professor of Sinhala in that university. What I said has much to do with decolonising social sciences and humanities and the contributions countries like ours can make to the global discourses of knowledge in these broad disciplines. I have previously discussed these issues in this column, including in my essay, ‘Does Sri Lanka Contribute to the Global Intellectual Expansion of Social Sciences and Humanities?’ published on 29 October 2025 and ‘Can Asians Think? Towards Decolonising Social Sciences and Humanities’ published on 31 December 2025.

At the recent talk, I posed a question that relates directly to what I have raised earlier but drew from a specific type of knowledge scholars like Prof Ananda Tissa Kumara have produced over a lifetime about our cultural worlds. I do not refer to their published work on Sinhala, Pali and Sanskrit languages, their histories or grammars; instead, their writing on various aspects of Sinhala culture. Erudite scholars familiar with Tamil sources have written extensively on Tamil culture in this same manner, which I will not refer to here.

To elaborate, let me refer to a several essays written by Professor Tissa Kumara over the years in the Sinhala language: 1) Aspects of Sri Lankan town planning emerging from Sinhala Sandesha poetry; 2) Health practices emerging from inscriptions of the latter part of the Anuradhapura period; 3) Buddhist religious background described in inscriptions of the Kandyan period; 4) Notions of aesthetic appreciation emerging from Sigiri poetry; 5) Rituals related to Sinhala clinical procedures; 6) Customs linked to marriage taboos in Sinhala society; 7) Food habits of ancient and medieval Lankans; and 8) The decline of modern Buddhist education. All these essays by Prof. Tissa Kumara and many others like them written by others remain untranslated into English or any other global language that holds intellectual power. The only exceptions would be the handful of scholars who also wrote in English or some of their works happened to be translated into English, an example of the latter being Prof. M.B. Ariyapala’s classic, Society in Medieval Ceylon.

The question I raised during my lecture was, what does one do with this knowledge and whether it is not possible to use this kind of knowledge profitably for theory building, conceptual and methodological fine-tuning and other such essential work mostly in the domain of abstract thinking that is crucially needed for social sciences and humanities. But this is not an interest these scholars ever entertained. Except for those who wrote fictionalised accounts such as unsubstantiated stories on mythological characters like Rawana, many of these scholars amassed detailed information along with their sources. This focus on sources is evident even in the titles of many of Prof. Tissa Kumara’s work referred to earlier. Rather than focusing on theorising or theory-based interpretations, these scholars’ aim was to collect and present socio-cultural material that is inaccessible to most others in society including people like myself. Either we know very little of such material or are completely unaware of their existence. But they are important sources of our collective history indicating what we are where we have come from and need to be seen as a specific genre of research.

In this sense, people like Prof. Tissa Kumara and his predecessors are human encyclopedias. But the knowledge they produced, when situated in the context of global knowledge production in general, remains mostly as ‘raw’ information albeit crucial. The pertinent question now is what do we do with this information? They can, of course, remain as it is. My argument however is this knowledge can be a serious source for theory-building and constructing philosophy based on a deeper understanding of the histories of our country and of the region and how people in these areas have dealt with the world over time.

Most scholars in our country and elsewhere in the region believe that the theoretical and conceptual apparatuses needed for our thinking – clearly manifest in social sciences and humanities – must necessarily be imported from the ‘west.’ It is this backward assumption, but specifically in reference to Indian experiences on social theory, that Prathama Banerjee and her colleagues observe in the following words: “theory appears as a ready-made body of philosophical thought, produced in the West …” As they further note, in this situation, “the more theory-inclined among us simply pick the latest theory off-the-shelf and ‘apply’ it to our context” disregarding its provincial European or North American origin, because of the false belief “that “‘theory’ is by definition universal.” What this means is that like in India, in countries like ours too, the “relationship to theory is dependent, derivative, and often deeply alienated.”

In a somewhat similar critique in his 2000 book, Provincialising Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference Dipesh Chakrabarty points to the limitations of Western social sciences in explaining the historical experiences of political modernity in South Asia. He attempted to renew Western and particularly European thought “from and for the margins,” and bring in diverse histories from regions that were marginalised in global knowledge production into the mainstream discourse of knowledge. In effect, this means making histories of countries like ours relevant in knowledge production.

The erroneous and blind faith in the universality of theory is evident in our country too whether it is the unquestioned embrace of modernist theories and philosophies or their postmodern versions. The heroes in this situation generally remain old white men from Marx to Foucault and many in between. This indicates the kind of unhealthy dependence local discourses of theory owe to the ‘west’ without any attempt towards generating serious thinking on our own.

In his 2002 essay, ‘Dismal State of Social Sciences in Pakistan,’ Akbar Zaidi points out how Pakistani social scientists blindly apply imported “theoretical arguments and constructs to Pakistani conditions without questioning, debating or commenting on the theory itself.” Similarly, as I noted in my 2017 essay, ‘Reclaiming Social Sciences and Humanities: Notes from South Asia,’ Sri Lankan social sciences and humanities have “not seriously engaged in recent times with the dominant theoretical constructs that currently hold sway in the more academically dominant parts of the world.” Our scholars also have not offered any serious alternate constructions of their own to the world without going crudely nativistic or exclusivist.

This situation brings me back to the kind of knowledge that scholars like Prof. Tissa Kumara have produced. Philosophy, theory or concepts generally emerge from specific historical and temporal conditions. Therefore, they are difficult to universalise or generalise without serious consequences. This does not mean that some ideas would not have universal applicability with or without minor fine tuning. In general, however, such bodies of abstract knowledge should ideally be constructed with reference to the histories and contemporary socio-political circumstances

from where they emerge that may have applicability to other places with similar histories. This is what Banerjee and her colleagues proposed in their 2016 essay, ‘The Work of Theory: Thinking Across Traditions’. This is also what decolonial theorists such as Walter Mignolo, Enrique Dussel and Aníbal Quijano have referred to as ‘decolonizing Western epistemology’ and ‘building decolonial epistemologies.’

My sense is, scholars like Prof. Tissa Kumara have amassed at least some part of such knowledge that can be used for theory-building that has so far not been used for this purpose. Let me refer to two specific examples that have local relevance which will place my argument in context. Historian and political scientist Benedict Anderson argued in his influential 1983 book, Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism that notions of nationalism led to the creation of nations or, as he calls them, ‘imagined communities.’ For him, unlike many others, European nation states emerged in response to the rise of ‘nationalism’ in the overseas European settlements, especially in the Western Hemisphere. But it was still a form of thinking that had Europe at its center.

Comparatively, we can consider Stephen Kemper’s 1991 book, The Presence of the Past: Chronicles, Politics, and Culture in Sinhala Life where the American anthropologist explored the ways in which Sinhala ‘national’ identity evolved over time along with a continual historical consciousness because of the existence of texts such as Mahawamsa. In other words, the Sinhala past manifests with social practices that have continued from the ancient past among which are chronicle-keeping, maintaining sacred places, and venerating heroes.

In this context, his argument is that Sinhala nationalism predates the rise of nationalist movements in Europe by over a thousand years, thereby challenging the hegemonic arguments such as those of Anderson, Ernest Gellner, Elie Kedourie and others who link nationalism as a modern phenomenon impacted by Europe in some way or another. Kemper was able to come to his interpretation by closely reading Lankan texts such as Mahawamsa and other Pali chronicles and more critically, theorizing what is in these texts. Such interpretable material is what has been presented by Prof. Tissa Kumara and others, sans the sing.

Similarly, local texts in Sinhala such as kadaim poth’ and vitti poth, which are basically narratives of local boundaries and descriptions of specific events written in the Dambadeniya and Kandyan periods are replete with crucial information. This includes local village and district boundaries, the different ethno-cultural groups that lived in and came to settle in specific places in these kingdoms, migratory events, wars and so on. These texts as well as European diplomatic dispatches and political reports from these times, particularly during the Kandyan period, refer to the cosmopolitanism in the Kandyan kingdom particularly its court, the military, town planning and more importantly the religious tolerance which even surprised the European observers and latter-day colonial rulers. Again, much of this comes from local sources or much less focused upon European dispatches of the time.

Scholars like Prof. Tissa Kumara have collected this kind of information as well as material from much older times and sources. What would the conceptual categories, such as ethnicity, nationalism, cosmopolitanism be like if they are reinterpreted or cast anew through these histories, rather than merely following their European and North American intellectual and historical slants which is the case at present? Among the questions we can ask are, whether these local idiosyncrasies resulted from Buddhism or local cultural practices we may not know much about at present but may exist in inscriptions, in ola leaf manuscripts or in other materials collected and presented by scholars such as Prof. Tissa Kumara.

For me, familiarizing ourselves with this under- and unused archive and employing them for theory-building as well as for fine-tuning what already exists is the main intellectual role we can play in taking our cultural knowledge to the world in a way that might make sense beyond the linguistic and socio-political borders of our country. Whether our universities and scholars are ready to attempt this without falling into the trap of crude nativisms, be satisfied with what has already been collected, but is untheorized or if they would rather lackadaisically remain shackled to ‘western’ epistemologies in the sense articulated by decolonial theorists remains to be seen.

Features

Extinction in isolation: Sri Lanka’s lizards at the climate crossroads

Climate change is no longer a distant or abstract threat to Sri Lanka’s biodiversity. It is already driving local extinctions — particularly among lizards trapped in geographically isolated habitats, where even small increases in temperature can mean the difference between survival and disappearance.

According to research by Buddhi Dayananda, Thilina Surasinghe and Suranjan Karunarathna, Sri Lanka’s narrowly distributed lizards are among the most vulnerable vertebrates in the country, with climate stress intensifying the impacts of habitat loss, fragmentation and naturally small population sizes.

Isolation Turns Warming into an Extinction Trap

Sri Lanka’s rugged topography and long geological isolation have produced extraordinary levels of reptile endemism. Many lizard species are confined to single mountains, forest patches or rock outcrops, existing nowhere else on Earth. While this isolation has driven evolution, it has also created conditions where climate change can rapidly trigger extinction.

“Lizards are especially sensitive to environmental temperature because their metabolism, activity patterns and reproduction depend directly on external conditions,” explains Suranjan Karunarathna, a leading herpetologist and co-author of the study. “When climatic thresholds are exceeded, geographically isolated species cannot shift their ranges. They are effectively trapped.”

The study highlights global projections indicating that nearly 40 percent of local lizard populations could disappear in coming decades, while up to one-fifth of all lizard species worldwide may face extinction by 2080 if current warming trends persist.

- Cnemaspis_gunawardanai (Adult Female), Pilikuttuwa, Gampaha District

- Cnemaspis_ingerorum (Adult Male), Sithulpauwa, Hambantota District

- Cnemaspis_hitihamii (Adult Female), Maragala, Monaragala District

- Cnemaspis_gunasekarai (Adult Male), Ritigala, Anuradapura District

- Cnemaspis_dissanayakai (Adult Male), Dimbulagala, Polonnaruwa District

- Cnemaspis_kandambyi (Adult Male), Meemure, Matale District

Heat Stress, Energy Loss and Reproductive Failure

Rising temperatures force lizards to spend more time in shelters to avoid lethal heat, reducing their foraging time and energy intake. Over time, this leads to chronic energy deficits that undermine growth and reproduction.

“When lizards forage less, they have less energy for breeding,” Karunarathna says. “This doesn’t always cause immediate mortality, but it slowly erodes populations.”

Repeated exposure to sub-lethal warming has been shown to increase embryonic mortality, reduce hatchling size, slow post-hatch growth and compromise body condition. In species with temperature-dependent sex determination, warming can skew sex ratios, threatening long-term population viability.

“These impacts often remain invisible until populations suddenly collapse,” Karunarathna warns.

Tropical Species with No Thermal Buffer

The research highlights that tropical lizards such as those in Sri Lanka are particularly vulnerable because they already live close to their physiological thermal limits. Unlike temperate species, they experience little seasonal temperature variation and therefore possess limited behavioural or evolutionary flexibility to cope with rapid warming.

“Even modest temperature increases can have severe consequences in tropical systems,” Karunarathna explains. “There is very little room for error.”

Climate change also alters habitat structure. Canopy thinning, tree mortality and changes in vegetation density increase ground-level temperatures and reduce the availability of shaded refuges, further exposing lizards to heat stress.

Narrow Ranges, Small Populations

Many Sri Lankan lizards exist as small, isolated populations restricted to narrow altitudinal bands or specific microhabitats. Once these habitats are degraded — through land-use change, quarrying, infrastructure development or climate-driven vegetation loss — entire global populations can vanish.

“Species confined to isolated hills and rock outcrops are especially at risk,” Karunarathna says. “Surrounding human-modified landscapes prevent movement to cooler or more suitable areas.”

Even protected areas offer no guarantee of survival if species occupy only small pockets within reserves. Localised disturbances or microclimatic changes can still result in extinction.

Climate Change Amplifies Human Pressures

The study emphasises that climate change will intensify existing human-driven threats, including habitat fragmentation, land-use change and environmental degradation. Together, these pressures create extinction cascades that disproportionately affect narrowly distributed species.

“Climate change acts as a force multiplier,” Karunarathna explains. “It worsens the impacts of every other threat lizards already face.”

Without targeted conservation action, many species may disappear before they are formally assessed or fully understood.

Science Must Shape Conservation Policy

Researchers stress the urgent need for conservation strategies that recognise micro-endemism and climate vulnerability. They call for stronger environmental impact assessments, climate-informed land-use planning and long-term monitoring of isolated populations.

“We cannot rely on broad conservation measures alone,” Karunarathna says. “Species that exist in a single location require site-specific protection.”

The researchers also highlight the importance of continued taxonomic and ecological research, warning that extinction may outpace scientific discovery.

A Vanishing Evolutionary Legacy

Sri Lanka’s lizards are not merely small reptiles hidden from view; they represent millions of years of unique evolutionary history. Their loss would be irreversible.

“Once these species disappear, they are gone forever,” Karunarathna says. “Climate change is moving faster than our conservation response, and isolation means there are no second chances.”

By Ifham Nizam ✍️

Features

Online work compatibility of education tablets

Enabling Education-to-Income Pathways through Dual-Use Devices

The deployment of tablets and Chromebook-based devices for emergency education following Cyclone Ditwah presents an opportunity that extends beyond short-term academic continuity. International experience demonstrates that the same category of devices—when properly governed and configured—can support safe, ethical, and productive online work, particularly for youth and displaced populations. This annex outlines the types of online jobs compatible with such devices, their technical limitations, and their strategic national value within Sri Lanka’s recovery and human capital development agenda.

Compatible Categories of Online Work

At the foundational level, entry-level digital jobs are widely accessible through Android tablets and Chromebook devices. These roles typically require basic digital literacy, language comprehension, and sustained attention rather than advanced computing power. Common examples include data tagging and data validation tasks, AI training activities such as text, image, or voice labelling, online surveys and structured research tasks, digital form filling, and basic transcription work. These activities are routinely hosted on Google task-based platforms, global AI crowdsourcing systems, and micro-task portals operated by international NGOs and UN agencies. Such models have been extensively utilised in countries including India, the Philippines, Kenya, and Nepal, particularly in post-disaster and low-income contexts.

At an intermediate level, freelance and gig-based work becomes viable, especially when Chromebook tablets such as the Lenovo Chromebook Duet or Acer Chromebook Tab are used with detachable keyboards. These devices are well suited for content writing and editing, Sinhala–Tamil–English translation work, social media management, Canva-based design assignments, and virtual assistant roles. Chromebooks excel in this domain because they provide full browser functionality, seamless integration with Google Docs and Sheets (including offline drafting and later (synchronization), reliable file upload capabilities, and stable video conferencing through platforms such as Google Meet or Zoom. Freelancers across Southeast Asia and Africa already rely heavily on Chromebook-class devices for such work, demonstrating their suitability in bandwidth- and power-constrained environments.

A third category involves remote employment and structured part-time work, which is also feasible on Chromebook tablets when paired with a keyboard and headset. These roles include online tutoring support, customer service through chat or email, research assistance, and entry-level digital bookkeeping. While such work requires a more consistent internet connection—often achievable through mobile hotspots—it does not demand high-end hardware. The combination of portability, long battery life, and browser-based platforms makes these devices adequate for such employment models.

Functional Capabilities and Limitations

It is important to clearly distinguish what these devices can and cannot reasonably support. Tablets and Chromebooks are highly effective for web-based jobs, Google Workspace-driven tasks, cloud platforms, online interviews conducted via Zoom or Google Meet, and the use of digital wallets and electronic payment systems. However, they are not designed for heavy video editing, advanced software development environments, or professional engineering and design tools such as AutoCAD. This limitation does not materially reduce their relevance, as global labour market data indicate that approximately 70–75 per cent of online work worldwide is browser-based and fully compatible with tablet-class devices.

Device Suitability for Dual Use

Among commonly deployed devices, the Chromebook Duet and Acer Chromebook Tab offer the strongest balance between learning and online work, making them the most effective all-round options. Android tablets such as the Samsung Galaxy Tab A8 or A9 and the Nokia T20 also perform reliably when supplemented with keyboards, with the latter offering particularly strong battery endurance. Budget-oriented devices such as the Xiaomi Redmi Pad remain suitable for learning and basic work tasks, though with some limitations in sustained productivity. Across all device types, battery efficiency remains a decisive advantage.

Power and Energy Considerations

In disaster-affected and power-scarce environments, tablets outperform conventional laptops. A battery life of 10–12 hours effectively supports a full day of online work or study. Offline drafting of documents with later synchronisation further reduces dependence on continuous connectivity. The use of solar chargers and power banks can extend operational capacity significantly, making these devices particularly suitable for temporary shelters and community learning hubs.

Payment and Income Feasibility in the Sri Lankan Context

From a financial inclusion perspective, these devices are fully compatible with commonly used payment systems. Platforms such as PayPal (within existing national constraints), Payoneer, Wise, LankaQR, local banking applications, and NGO stipend mechanisms are all accessible through Android and ChromeOS environments. Notably, many Sri Lankan freelancers already conduct income-generating activities entirely via mobile devices, confirming the practical feasibility of tablet-based earning.

Strategic National Value

The dual use of tablets for both education and income generation carries significant strategic value for Sri Lanka. It helps prevent long-term dependency by enabling families to rebuild livelihoods, creates structured earning pathways for youth, and transforms disaster relief interventions into resilience-building investments. This approach supports a human resource management–driven recovery model rather than a welfare-dependent one. It aligns directly with the outcomes sought by the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Labour and HRM reform initiatives, and broader national productivity and competitiveness goals.

Policy Positioning under the Vivonta / PPA Framework

Within the Vivonta/Proprietary Planters Alliance national response framework, it is recommended that these devices be formally positioned as “Learning + Livelihood Tablets.” This designation reflects their dual public value and supports a structured governance approach. Devices should be configured with dual profiles—Student and Worker—supplemented by basic digital job readiness modules, clear ethical guidance on online work, and safeguards against exploitation, particularly for vulnerable populations.

Performance Indicators

From a monitoring perspective, the expected reach of such an intervention is high, encompassing students, youth, and displaced adults. The anticipated impact is very high, as it directly enables the transition from education to income generation. Confidence in the approach is high due to extensive global precedent, while the required effort remains moderate, centering primarily on training, coordination, and platform curation rather than capital-intensive investment.

We respectfully invite the Open University of Sri Lanka, Derana, Sirasa, Rupavahini, DP Education, and Janith Wickramasinghe, National Online Job Coach, to join hands under a single national banner—

“Lighting the Dreams of Sri Lanka’s Emerging Leaders.”

by Lalin I De Silva, FIPM (SL) ✍️

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoKoaloo.Fi and Stredge forge strategic partnership to offer businesses sustainable supply chain solutions

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoSLT MOBITEL and Fintelex empower farmers with the launch of Yaya Agro App

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoHayleys Mobility unveils Premium Delivery Centre

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended