Features

The Ceylon Journal, Vol. 1 No. 2:A remarkable production

Reivew by Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

Edited by Avisha Mario Seneviratne

When over forty years ago I produced the first volume of the New Lankan Review, which proved popular if controversial, I realised that the real test would be producing a sequel. That was managed after a year, and I continued publication over eight volumes, stopping with a memorial volume for Richard de Zoysa after his death, for by then I had got Channels going, the journal of the English Writers Cooperative. That had more limited scope, for it was about creative writing, whereas NLR had had social criticism too. But by 1990, I felt it was time to move on to other things, and began my intensive work with regard to English Language Teaching.

This preamble is because I have to express my congratulations to Avishka Mario Seneviratne for having so swiftly produced a second number of his Ceylon Journal, ably fulfilling his commitment to make it a bi-annual publication. And once again he has amply justified his commitment to expanding understanding of ‘the very many facets of the history of Sri Lanka’

A couple of writers feature again after their fascinating contributions to the first number. But they deal here with very different subjects, the distinguished historian C. R. de Silva moving from a study of Galle to an account of Dona Catherina, whom the Portuguese hoped would be a puppet sovereign of Kandy, but who instead provided legitimacy to Vimaladharmasuriya, who wrenched the kingdom from Portuguese control.

Avishka himself, having written previously about the enigmatic Ronald Raven Hart, moves to the inspiration for the Journal, Charles Ambrose Lorenz, and has a fascinating account of his work and the contemporaries who helped him along. The glimpses of giants of the last century, such as Christoper Elliott and Richard Morgan, and the Britishers who ran the place including the intellectual Emerson Tennent who sadly supported the excesses of Viscount Torrington during the 1848 rebellion, are richly evocative of those distant days. And happily Avishka illustrates the article with reproductions of Lorenz’s caricatures of his contemporaries.

The volume is dedicated to Fr. S. G. Perera, whose history textbook was a staple in schools for many years. There is a rich account of how he filled the gap when there was no material for the study of local history, even though one of the more enlightened British governors noted the need for schools to take this up. And that article is followed by a helpful bibliography of Fr. Perera’s publications, which include interestingly ‘A Priest’s Letters to a Niece on Love, Courtship and Marriage’.

There are two interesting excursions into the byways of our history. Manohara de Silva, who had written in the previous number, now deals with the ambiguities in the different versions of the 1815 convention, and notes how the British won round the Buddhist clergy by a different version in Sinhala about the primacy of not just Buddhism but the Buddha Sasana, which would include the Sangha. Very different is the account of the Nittaewa, in which Pradeep Jayatunga, looks at two very different early accounts, and concludes that evidence of a human dimension has been crowded out by stress on bestial characteristics.

Fascinating was the account of a now almost forgotten politician, Wijayananda Dahanayake, who was briefly Prime Minister. This was almost by accident since the most senior member of the cabinet, C P de Silva, was away when Bandaranaike was assassinated and Dahanayake had been acting. He had a glorious time, sacking the ministers who had contributed to his elevation, and then setting up a political party which won no seats at all in the election that followed. But he was back in the July election, and then became a Minister in the UNP government of 1965, though he left that party soon after its defeat in 1970.

But he was back again, not in 1977, when he lost as an independent, but shortly thereafter when he had got the victorious candidate for Galle unseated through an election petition which he argued himself. And having then come in as a UNP candidate in the by-election, he was briefly made a Minister by J R Jayewardene, before that long parliament was finally dissolved in 1988.

As with most of the articles in the Journal, the meat of the account of Dahanayake is not in the record of his life in parliament but rather in the personal touches. Some of the anecdotes are well known, such as his donning of a loincloth to protest against state restrictions on dress material, but even more telling is his producing in parliament the jacket of a hospital attendant and telling the Speaker, a renowned philanderer, that he was sure he was quite familiar with this. And perhaps most characteristic of the man was his reply when asked why he travelled in third class in trains, when parliamentarians were given first class tickets, that it was because there was no fourth class.

I have dwelt at length on Dahanayake because I have a soft spot for him. Embedded in my memory is a journey in his car from Kandy when he gave me a lift, after we had both been staying with the Government Agent W J Fernando, and he enriched the journey with a disquisition of the joys of English literature. He was immensely erudite, and the article captures that as well as his entertaining quixoticism.

Then there are two pieces about interesting visitors to this country in the first couple of decades after independence. Malaka Talwatte writes about Taprobane Island, which was rented for many years by the American writer Paul Bowles. Amongst his guests was Peggy Guggenheim, and the article expands on her contribution to enhancing the appreciation of modern art. When I was very young I read about this dimension of the contribution of that extraordinary family to the display of art, but I did not know before that she had spent some time in this country.

The second about visitors is related to this, in that it deals with Donald Friend, who spent several years with Bevis Bawa at Brief. The latter took Friend on a visit to Taprobane Island when Bowles was there, and wrote about the problems Bowles had with the locals. That was the main reason he left the place.

The writer of ‘Friends of Friend’, Srilal Perera, is not described in the note with which the volume begins, giving details of the writers. I have no idea then of his background, but he must be congratulated for a rich account of not only artists such as the architect Ulrik Plesner, but also the controversial planter Mark Bracegirdle whom a Governor had tried to deport in the thirties. The connection is tenuous, for Friend lived in Ceylon in the fifties, but a biographer noted that he moved in the same circles as Bracegirdle in London after he had left Ceylon.

Another cultural activist who did much for the country is commemorated in an article by Michael Meyler, who is described as a language teacher, writer and editor. He writes about Richard Boyle, who died in 2023. Having come out first to Sri Lanka in 1973 to work on the not very successful film ‘The God King’ with Lester James Peries, he was so taken with the country that he was involved in two more films here during the next few years, including with the redoubtable Manik Sandrasagara.

Meyler is most entertaining about the various projects Manik devised which Richard tried to support, but more fulfillingly he met here his future wife Sharmini Chanmugam, and they set up their own video production company. Their work was much appreciated, and they were commissioned to create memorable accounts of the country, though Richard also worked on a series of books which explored elements of our languages and interesting personalities.

I have written at some length about many articles in the second Ceylon Journal, and still not mentioned the keynote piece which records many depictions of Adam’s Peak through the ages, in literature and through sketches. The article, by Donald Stadtner, an American academic, has fabulous illustrations from a 15th century manuscript now in Paris, about which I had known nothing previously. It deserves to be better known, and the writer and the editor must be congratulated for giving it a wider audience.

In addition to the many articles, the journal has a note about the launch of the first number last August, and reproduces the text of the thought-provoking keynote address made by Rohan Pethiyagoda. In tracing the history of rubber cultivation, he touches on social and economic changes which rubber supported, and regrets what he sees as a mindless reaction to colonialism so that ‘We rejected the good values of the West along with the bad: like courtesy, queueing and the idea that corruption is wrong’.

The journal is a remarkable production and, since the second lived up to the first, I am sure the third will appear soon and continue with similar excellence.

Features

Thousands celebrate a chief who will only rule for eight years

Thousands of people have been gathering in southern Ethiopia for one of the country’s biggest cultural events.

The week-long Gada ceremony, which ended on Sunday, sees the official transfer of power from one customary ruler to his successor – something that happens every eight years.

The tradition of regularly appointing a new Abbaa Gadaa has been practised by the Borana community for centuries – and sees them gather at the rural site of Arda Jila Badhasa, near the Ethiopian town of Arero.

It is a time to celebrate their special form of democracy as well as their cultural heritage, with each age group taking the opportunity to wear their different traditional outfits.

These are paraded the day before the official handover during a procession when married women march with wooden batons, called “siinqee”.

[BBC]

The batons have symbolic values of protection for women, who use them during conflict.

If a siinqee stick is placed on the ground by a married woman between two quarrelling parties, it means the conflict must stop immediately out of respect.

During the procession, younger women lead at the front, distinguished from the married women by the different colour of their clothing.

[BBC]

In this pastoralist society women are excluded from holding the top power of Abbaa Gadaa, sitting on the council of elders or being initiated into the system as a child.

But their important role can be seen during the festival as they build all the accommodation for those staying for the week – and prepare all the food.

And the unique Gada system of governance, which was added to the UN’s cultural heritage list in 2016, allows for them to attend regular community meetings and to voice their opinions to the Abbaa Gadaa.

Gada membership is only open to boys whose fathers are already members – young initiates have their heads shaven at the crown to make their rank clear.

The smaller the circle, the older he is.

As the global cultural body UNESCO reports, oral historians teach young initiates about “history, laws, rituals, time reckoning, cosmology, myths, rules of conduct, and the function of the Gada system”.

Training for boys begins as young as eight years old. Later, they will be assessed for their potential as future leaders.

As they grow up, tests include walking long distances barefoot, slaughtering cattle efficiently and showing kindness to fellow initiates.

Headpieces made from cowrie shells are traditionally worn by young trainees. The only other people allowed to wear them are elderly women.

Both groups are revered by Borana community members.

Men aged between 28 and 32 are identified by the ostrich feathers they wear, which are known in the Afaan Oromo language as “baalli”.

Their attendance at the Gada ceremony is an opportunity to learn, prepare and bond as it is already known who the Abbaa Gadaa from this age group will be taking power in 2033.

The main event at the recent Gada ceremony was the handover of power, from the outgoing 48-year-old Abbaa Gadaa to his younger successor.

Well-wishers crossed the border from Kenya and others travelled from as far as Ethiopia’s capital, Addis Ababa, to witness the spectacle. The governor of Kenya’s Marsabit county was among the honoured guests.

Thirty-seven-year-old Guyo Boru Guyo, seen here holding a spear, was chosen to lead because he impressed the council of elders during his teenage years.

[BBC]

He becomes the 72nd Abbaa Gadaa and will now oversee the Borana community across borders – in southern Ethiopia and north-western Kenya.

As their top diplomat, he will also be responsible for solving feuds that rear their heads for pastoralists. These often involve cattle raiding and disputes over access to water in this drought-prone region.

During his eight years at the helm, his successor will finish his training to take on the job in continuation of this generations-old tradition.

[BBC]

Features

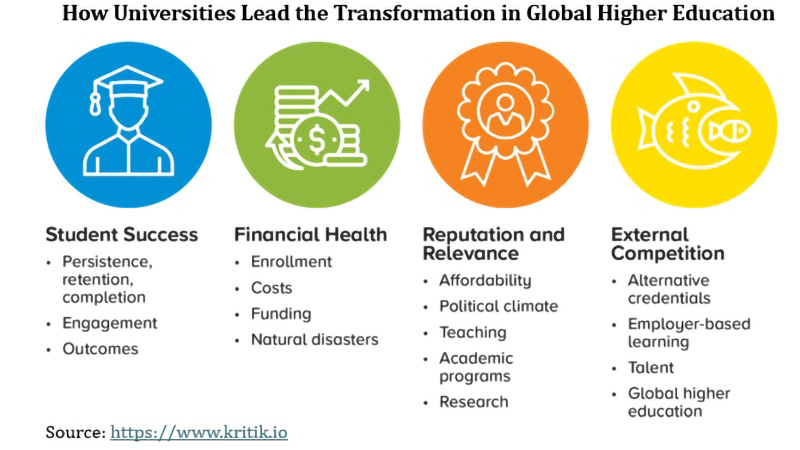

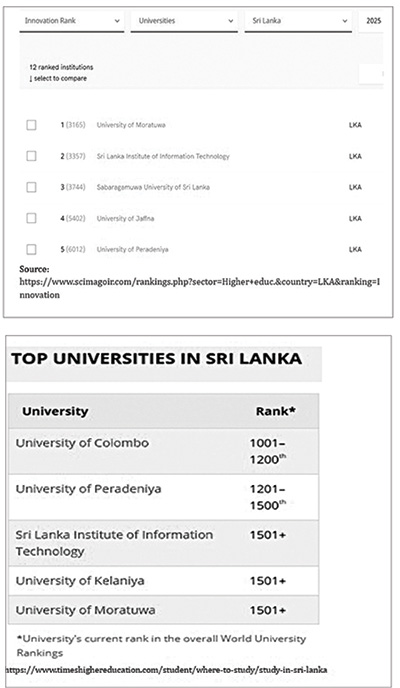

How universities lead transformation in global higher education

To establish a high-quality educational institution, it is essential to create a sustainable and flexible foundation that meets contemporary educational needs while adapting to future demands. The following outline a robust model for a successful and reputable educational institution. (See Image 1 and Graphs 1 and 2)

To establish a high-quality educational institution, it is essential to create a sustainable and flexible foundation that meets contemporary educational needs while adapting to future demands. The following outline a robust model for a successful and reputable educational institution. (See Image 1 and Graphs 1 and 2)

Faculty Excellence and Research Integration: Recruit faculty members with advanced qualifications, industry experience, and a strong commitment to student development. Integrate research as a cornerstone of teaching to encourage innovation, critical inquiry, and evidence-based learning. Establish dedicated research groups and facilities, fostering a vibrant research culture, led by senior academics, and providing hands-on research experience for students.

Infrastructure and Learning Environment: Develop modern, accessible campuses that accommodate diverse learning needs and provide a conducive environment for academic and extracurricular activities. Invest in state-of-the-art facilities, including libraries, laboratories, collaborative workspaces, and recreational areas to support well-rounded student development. Utilize technology-enhanced classrooms and virtual learning platforms to create dynamic and interactive learning experiences.

Global Partnerships and Multicultural Environment: Promote partnerships with reputable international universities and organizations to provide global exposure and collaborative opportunities. Encourage student and faculty exchange programmes, joint research, and international internships, broadening perspectives and building cross-cultural competencies. Cultivate a multicultural campus environment that embraces diversity and prepares students to thrive in a globalized workforce.

Industry Engagement and Graduate Employability: Collaborate closely with industry partners to ensure that programmes meet professional standards and graduates possess relevant, in-demand skills. Embed practical experiences, such as internships and work placements, within the academic curriculum, to enhance employability. Establish a dedicated career services team to support job placement, career counselling, and networking opportunities, maintaining high graduate employment rates.

Student-Centric Support Systems and Life Skills: Offer comprehensive student support services, including academic advising, mental health resources, and career development programmes. Provide opportunities for students to develop essential life skills such as teamwork, leadership, communication, and resilience. Promote a balanced academic and social life by fostering clubs, sports, and recreational activities that contribute to personal growth and community engagement.

Commitment to Sustainability and Social Responsibility: Integrate sustainability into campus operations and curricula, preparing students to lead in a sustainable future. Encourage social responsibility through community engagement, service-learning projects, and ethical research initiatives. Implement eco-friendly practices across campus, from energy-efficient buildings to waste reduction, promoting environmental awareness.

Governance, Independence, and Financial Sustainability: Establish transparent, ethical governance structures that promote accountability, inclusivity, and long-term planning. Strive for financial independence by building a sustainable revenue model that balances tuition, grants, partnerships, and philanthropic contributions. Prioritize flexibility in governance to adapt quickly to external changes while safeguarding institutional autonomy.

By emphasizing quality, inclusivity, innovation, and adaptability, an educational institution can cultivate a culture of academic excellence and social responsibility, producing well-rounded graduates who are equipped to succeed and contribute meaningfully to society. This framework provides a strategic approach to building an institution that thrives academically, socially, and economically.

Critique of the Traditional Sri Lankan University System

Outdated Curriculum and Lack of Industry Relevance: Many traditional universities in Sri Lanka operate with rigid curricula that are slow to adapt to rapidly changing industry needs, leaving graduates underprepared for the global workforce. Syllabi are often centered around theoretical knowledge with limited focus on practical, hands-on experience, problem-solving, and critical thinking skills.

Outdated Curriculum and Lack of Industry Relevance: Many traditional universities in Sri Lanka operate with rigid curricula that are slow to adapt to rapidly changing industry needs, leaving graduates underprepared for the global workforce. Syllabi are often centered around theoretical knowledge with limited focus on practical, hands-on experience, problem-solving, and critical thinking skills.

Insufficient Research and Innovation Focus: The Sri Lankan university system places minimal emphasis on research, innovation, and practical application, which hinders the development of a strong research culture. Limited funding, resources, and incentives for faculty and students to pursue cutting-edge research reduce international visibility and publications, key factors in global rankings.

Lack of International Partnerships and Exposure: Traditional universities have minimal collaboration with foreign institutions, limiting opportunities for student exchange programmes, collaborative research, and global internships. This lack of exposure restricts students’ cultural awareness, adaptability, and networking skills, which are essential in today’s globalized economy.

Bureaucratic Governance and Inflexibility: Highly centralized and bureaucratic governance structures result in slow decision-making, stifling innovation and responsiveness to changing educational demands. Universities face significant limitations in introducing new programmes, hiring qualified faculty, and allocating resources, which affects their competitive edge and ability to adapt.

Underfunded Infrastructure and Resources: The lack of adequate funding for state-of-the-art infrastructure, technological resources, and modern learning spaces reduces the quality of education and student experience. Insufficient investment in libraries, laboratories, and virtual learning tools limits access to essential resources needed to build research capabilities and attract international students.

Limited Emphasis on Student-Centric Support Services: Support services such as career counselling, academic advising, and mental health resources are insufficiently developed in many institutions, impacting students’ overall well-being and employability. Universities often lack the means to prepare students for the workforce beyond academics, which results in graduates with high academic knowledge but limited job-ready skills.

Recommended Transformations for World-Class Standards

Curriculum Revamp with a Focus on Industry Relevance: Shift towards an interdisciplinary, outcome-based curriculum that aligns with industry requirements and promotes experiential learning. Establish partnerships with industries to incorporate internships, co-ops, and project-based learning, providing students with practical skills. Incorporate modules on critical thinking, problem-solving, and digital literacy, which are essential for employability and adaptability.

Enhancing Research Capacity and Innovation Ecosystem: Allocate dedicated funding for research and establish incentives for faculty and students to publish in high-impact journals. Develop specialized research centres and labs focusing on areas critical to national and global challenges, such as technology, sustainable development, and public health. Foster innovation hubs, incubators, and accelerators, within universities, to support entrepreneurship and collaboration with the private sector, driving societal impact and ranking potential.

International Partnerships and Global Exposure: Form alliances with reputable international universities to offer dual degrees, joint research programmes, and student and faculty exchange opportunities. Encourage academic collaborations that enable students to work on global projects, thereby enhancing cultural competence and preparing them for international careers. Create virtual exchange programmes and international seminars to engage students in global conversations without extensive travel requirements.

Autonomous and Responsive Governance: Decentralize governance to allow universities to make independent decisions on programmes, faculty hiring, and funding allocation, fostering flexibility and responsiveness. Implement performance-based accountability systems for university administrators, rewarding institutions that achieve excellence in teaching, research, and innovation. Empower universities to secure alternate funding sources through grants, industry partnerships, and philanthropic contributions, ensuring financial stability and academic independence.

Investment in Infrastructure and Digital Transformation: Prioritize investment in modern campus facilities, advanced laboratories, and digital learning environments to provide students with a high-quality academic experience. Expand access to online learning resources, digital libraries, and virtual classrooms, offering students a more adaptable, blended learning model. Create dedicated spaces for collaborative learning and interdisciplinary activities, fostering a culture of innovation and teamwork.

Robust Student-Centric Support Systems: Establish comprehensive support services, including career development, mental health resources, and academic advising, to help students navigate both academic and personal challenges. Introduce career-oriented training programmes focusing on employability skills, including communication, networking, and leadership, to prepare students for the workforce. Develop alumni networks and mentorship programmes, connecting students with successful graduates for career guidance and networking opportunities.

Emphasis on Sustainability and Social Responsibility: Embed sustainability principles in campus operations, curricula, and research activities to align with global priorities and contribute to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Initiate community engagement programmes that encourage students to apply their knowledge in real-world settings, fostering social responsibility and regional development. Encourage environmental initiatives, like waste reduction, energy efficiency, and green campus policies, reflecting a commitment to global best practices.

By adopting these strategies, traditional Sri Lankan universities can transform into competitive, globally recognized institutions. This shift would enable them to improve international rankings, increase graduate employability, attract a diverse student body, and contribute meaningfully to both the local and global knowledge economies.

The traditional university system in Sri Lanka, while rich in history and academic legacy, faces significant challenges in meeting the demands of the modern, globally connected world. The system requires critical reforms to enhance its alignment with international standards, improve rankings, and produce graduates ready for today’s dynamic job market. This essay discusses the shortcomings of the existing system and provides actionable recommendations to enable Sri Lankan universities to transform into globally competitive, high-ranking institutions.

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT University, Malabe. He is also the author of the “Doing Social Research and Publishing Results”, a Springer publication (Singapore), and “Samaja Gaveshakaya (in Sinhala). The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the institution he works for. He can be contacted at saliya.a@slit.lk and www.researcher.com)

Features

Govt. needs to explain its slow pace

by Jehan Perera

It was three years ago that the Aragalaya people’s movement in Sri Lanka hit the international headlines. The world watched a celebration of democracy on the streets of Colombo as tens of thousands of people of all ages and communities gathered to demand a change of government. The Aragalaya showed that people have the power, and agency, to make governments at the time of elections and also break governments on the streets through non-violent mass protest. This is a very powerful message that other countries in the region, particularly Bangladesh and Pakistan in the South Asian region, have taken to heart from the example of Sri Lanka’s Aragalaya. It calls for adopting ‘systems thinking’ in which there is understanding of the interconnectedness of complex issues and working across different sectors and levels that address root causes rather than just the symptoms.

Democracy means that power is with the people and they do not surrender it to the government to become inert and let the government do as it wants, especially if it is harming the national interest. This also calls for collaboration across sectors, including political parties, businesses, NGOs and community groups, to create a collective effort towards change as it did during the Aragalaya. The government that the Aragalaya protest movement overthrew through street power was one that had been elected by a massive 2/3 majority that was unprecedented in the country under the proportional electoral system. It also had more than three years of its term remaining. But when it became clear that it was jeopardizing the national interest rather than furthering it, and inflicted calamitous economic collapse, the people’s power became unstoppable.

A similar situation arose in Bangladesh, a year ago, when the government of Sheikh Hasina decided to have a quota that favoured her ruling party’s supporters in the provision of scarce government jobs to the people. In the midst of economic hardship, this became a provocation to the people of Bangladesh. They saw the corruption and sense of entitlement in those who were ruling the country, just as the Sri Lankan people had seen in their own country two years earlier. This policy sparked massive student-led protests, with young people taking to the streets to demand equitable opportunities and an end to nepotistic practices. They followed the Sri Lankan example that they had seen on the television and social media to overthrow a government that had won the last election but was not delivering the results it had promised.

CONSTITUTIONAL PROCESS

Despite similarities, there are also major differences between Bangladesh and Sri Lankan uprisings. In Sri Lanka, the protest movement achieved its task with only a minimal loss of life. In Bangladesh, the people mobilized against the government which had become like a dictatorship and which used a high level of violence in trying to suppress the protests. In Sri Lanka, the transition process was the constitutionally mandated one and also took place non-violently. When President Gotabaya Rajapaksa resigned, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe succeeded him as the acting President, pending a vote in Parliament which he won. President Wickremesinghe selected his Cabinet of Ministers and governed until his presidential term ended. A new President Anura Kumara Dissanayake was elected at the presidential elections which were the most peaceful elections in the country’s history.

In Bangladesh, the fleeing abroad of Prime Minister Hasina was not followed by Parliament electing a new Prime Minister. Instead, the President of Bangladesh Mohammed Shahabuddin appointed an interim government, headed by NGO leader Muhammad Yunus. The question in Bangladesh is how long will this interim government continue to govern the country without elections. The mainstream political parties, including that of the deposed Prime Minister, are calling for early elections. However, the leaders of the protest movement that overthrew the government on the streets and who experienced a high level of violence do not wish elections to be held at this time. They call for a transitional justice process in which the truth of what happened is ascertained and those who used violence against the people are held accountable.

By way of contrast, in Sri Lanka, which went through a legal and constitutional process to achieve its change of government there is little or no demand for transitional justice processes against those who held office at the time of the Aragalaya protests. Even those against whom there are allegations of human rights violations and corruptions are permitted to freely contest the elections. But they were thoroughly defeated and the people elected a new NPP government with a 2/3 majority in Parliament, many of whom are new to politics and have no association with those who governed the country in the past. This is both a strength and a weakness. It is a strength in that the members of the new government are idealistic and sincere in their efforts to improve the life of the people. But their present non-consultative and self-reliant approach can lead to erroneous decisions, such as to centrally appoint a majority of council members, who are of Sinhalese ethnicity, to the Eastern University which has a majority of Tamil faculty and students.

UNRESOLVED PROBLEMS

The problem for the new government is that they inherited a country with massive unresolved problems, including the unresolved ethnic conflict which requires both sensitivity and consultations to resolve. The most pressing problem, by any measure, is the economic problem in which 25 percent of the population have fallen below the poverty line, which is double the percentage that existed three years ago. Despite the appearance of high-end consumer spending, the gap between the rich and poor has increased significantly. The day-to-day life of most people is how to survive economically. The former government put the main burden of repaying the foreign debts and balancing the budget on the poorer sections of the population while sparing those at the upper end, who are expected to be engines of the economy. The new government has to change this inequity but it has little leeway to do so, because the government’s treasury has been emptied by the misdeeds of the past.

Despite having a 2/3 majority in Parliament, the government is hamstrung by its lack of economic resources and the recalcitrance of the prevailing system that continues to be steeped in the ways of the past. President Dissanayake has been forthright about this when he addressed Parliament during the budget debate. He said, “the country has been transformed into a shadow criminal state. While we see a functioning police force, military, political authority and judiciary on the surface, beneath this structure exists an armed underworld with ties to law enforcement, security forces and legal professionals. This shadow state must be dismantled. There are two approaches to dealing with this issue: either aligning with the criminal underworld or decisively eliminating it. Unlike previous administrations, which coexisted with organized crime, the NPP-led government is determined to eradicate it entirely.”

Sri Lanka’s new government has committed to holding local government elections within two months unlike Bangladesh’s protest leaders, who demand that transitional justice and accountability for past crimes take precedence over elections. This decision aligns with constitutional mandates and upholds a Supreme Court ruling that the previous government had ignored. However, holding elections so soon after a major political shift poses risks. The new government has yet to deliver on key promises—bringing economic relief to struggling families and prosecuting those responsible for corruption. It needs to also address burning ethnic and religious grievances, such as the building of Buddhist religious sites where there are no members of that community living there. If voters lose patience, political instability could return. The people need to be farsighted when they make their decision to vote. As citizens they need to recognise that systemic change takes time.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoPrivate tuition, etc., for O/L students suspended until the end of exam

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoShyam Selvadurai and his exploration of Yasodhara’s story

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoCooking oil frauds

-

Editorial4 days ago

Editorial4 days agoRanil roasted in London

-

Latest News4 days ago

Latest News4 days agoS. Thomas’ beat Royal by five wickets in the 146th Battle of the Blues

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoTeachers’ union calls for action against late-night WhatsApp homework

-

Sports7 days ago

Sports7 days agoRoyal favourites at the 146th Battle of the Blues

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoHeroes and villains