Life style

Amphibians going extinct in SL at a record pace

by Ifham Nizam

Sri Lanka holds the record for nearly 14 per cent of the amphibian extinctions in the world. In other words, of the 130 amphibian extinctions known to have occurred across the globe, 18 extinctions (14 per cent) have occurred in Sri Lanka, says Dr. Anslem de Silva, widely regarded as the father of Herpetology in the country. Speaking to The Sunday Island, the authors of a news book on amphibians, said that this is one of the highest number of amphibian extinctions known from a single country. Some consider this unusual extinction rate to be largely the result of the loss of nearly 70 per cent of the island’s forest cover. Dr. Anslem de Silva, Co-Chairman, Amphibian Specialist Group, International Union for the Conservation of Nature/Species Survival Commission (IUCN/SSC), together with two academics, Dr. Kanishka Ukuwela, Senior Lecture at Rajarata University, Mihintale who is  also associated with IUCN/SSC and Dr. Dillan Chaturanga, Lecture at Ruhuna University, Matara had authored this most comprehensive book on amphibians running to nearly 250 pages released last week. The prevalent levels of application of agrochemicals up to few months back, especially in rice fields, and vegetable and tea plantations, have increased over the past three decades. Similarly, the release of untreated industrial wastewater to natural water bodies has intensified. As a consequence, many streams and canals have become highly polluted, they say. The use of pesticides directly decreases the insect population, an important source of food for amphibians. Furthermore, these pollutants can easily make the water in paddy fields and the insects on which the amphibians feed toxic or increase the nitrogen content of the water. The highly permeable skins of amphibians would certainly cause them to be directly affected by these, they add. Amphibian mortality due to road traffic is a widespread problem globally that has been known to be responsible for population reductions and even local extinction in certaininstances. In Sri Lanka, amphibian mortalities due to road traffic are highly prevalent on roads that serve paddy fields, wetlands and forests. Further, they are especially intensified on rainy days when amphibian activity is high, the book explains. Recent studies indicate that amphibian road kills are exacerbated in certain national parks in the country due to increased visitation. According to recent estimates, several thousand amphibians are killed annually due to road traffic.

also associated with IUCN/SSC and Dr. Dillan Chaturanga, Lecture at Ruhuna University, Matara had authored this most comprehensive book on amphibians running to nearly 250 pages released last week. The prevalent levels of application of agrochemicals up to few months back, especially in rice fields, and vegetable and tea plantations, have increased over the past three decades. Similarly, the release of untreated industrial wastewater to natural water bodies has intensified. As a consequence, many streams and canals have become highly polluted, they say. The use of pesticides directly decreases the insect population, an important source of food for amphibians. Furthermore, these pollutants can easily make the water in paddy fields and the insects on which the amphibians feed toxic or increase the nitrogen content of the water. The highly permeable skins of amphibians would certainly cause them to be directly affected by these, they add. Amphibian mortality due to road traffic is a widespread problem globally that has been known to be responsible for population reductions and even local extinction in certaininstances. In Sri Lanka, amphibian mortalities due to road traffic are highly prevalent on roads that serve paddy fields, wetlands and forests. Further, they are especially intensified on rainy days when amphibian activity is high, the book explains. Recent studies indicate that amphibian road kills are exacerbated in certain national parks in the country due to increased visitation. According to recent estimates, several thousand amphibians are killed annually due to road traffic.

Professor W. A. Priyanka, PhD (USA), Professor in Zoology, Faculty of Science, University of Peradeniya says the need for a guide to the amphibian fauna of Sri Lanka is obvious, given the currently critical conditions endangering them. Amphibians are an attractive group of animals whose diversity has always sparked interest among the scientific community, creating a vast body of unanswered questions.However, the identification of amphibians has been a challenge due to the lack of a complete and informative guide. The comprehensive pictorial guide provided by the new book should thus be of great benefit to a better understanding of the unique and intriguing nature of these fascinating living beings.The authors have done an outstanding job in compiling this book. An introduction to the guide briefly describes the history, current status, threats and conservation information, along with interesting folklore associated with amphibians. With the clear and informative images, distribution maps and updated status of each species, this guide can easily be comprehended by experts and beginners in the field alike.”I firmly believe that this book will be very useful to undergraduate and postgraduate students in the fields of zoology, biology and environmental science, as well as researchers, wildlife managers and visitors,” Professor Priyanka added.The authors said that like their previous guide to the reptiles of Sri Lanka, A Naturalist’s Guide to the Reptiles of Sri Lanka (de Silva & Ukuwela, 2017, 2020), this book is intended for both naturalists and visitors to Sri Lanka, providing an introduction to the amphibians found here. It features all the extant species of amphibian in this country with colour photographs and quick and easy tips for identification. At the time of writing, 120 species have been recorded within the country and ongoing taxonomic work is certain to add more to this impressive list in the next few years.This guide provides a general introduction to the amphibians of Sri Lanka, a profile of the physiographic, climatic, and vegetation features of the island, key characteristics that can be used in the identification of amphibians and descriptions of each extant amphibian species.Additionally, it presents information on amphibian conservation here and a brief introduction to folklore and traditional treatment methods for combating poisoning due to amphibians in this country. The species descriptions are arranged under their higher taxonomic groups(orders and families), and further grouped in their respective genera.The descriptions are organized in alphabetical order by their scientific names. Every species covered is accompanied by one or more colour photograph of the animal. Each account includes the vernacular name in English, the current scientific name, the vernacular name in Sinhala, a brief history of the species, a description with identification features, and details of habitat, habits and distribution (both here and outside the country).Key external identification features of the species, such as body form, skin texture and coloration, are provided, to help in the quick identification of an animal in the field.It must be noted that according to Sri Lanka’s wildlife laws, amphibians cannot be captured or removed from their natural habitats without official permits, which must be obtained in advance from the Department of Wildlife Conservation.Sri Lanka is home to an exceptional diversity of amphibians. Currently, the island nation boasts of 112 species of amphibians of which 98 are restricted to the country. However, nearly 60 per cent of this magnificent diversity is threatened with extinction. To make matters worse, very little attention is paid by the conservation authorities or the public. The last treatise on the subject was published 15 years ago. However, many changes have taken place since then and hence an updated compilation was a major necessity. This book by the three authors intends to popularize the study of amphibians by the general public by filling this large void. Historical aspects

Sri Lanka is one of the few countries in the world where conservation and protection of its fauna and flora has been practiced since pre-Christian times. There is much archaeological, historical and literary evidence to show that from ancient times amphibians have attracted the attention of the people of this island.

This is evident by the discovery of an ancient bronze cast of a frog (see photo) discovered during excavations conducted by the Department of Archaeology and the Central Cultural Fund. Strati-graphic evidence from the excavation sites indicate that these objects belong to the sixth to eighth centuries AD (Anuradhapura and Jetavanārāma museum records). Beliefs that feature the ‘good’ qualities of frogs and association with nature. These beliefs have some positive effects on the conservation of amphibians, perhaps one reason that Sri Lanka harbours a diverse assemblage of frogs. Absence of frogs and toads in agricultural fields indicates impending crop failure, it is believed.

The authors have specially thanked Managing Director John Beaufoy of John Beaufoy Publishing Ltd, for publishing many books promoting Sri Lanka diversity.

Life style

What I Do, What I Love: A Life Shaped by Art, Wilderness and Truth

In a country where creative pursuits are often treated as indulgences rather than vocations, Saman Halloluwa’s journey stands apart — carved patiently through brushstrokes, framed through a camera lens, and articulated through the written word. Painter, wildlife and nature photographer, and independent environmental journalist, Halloluwa inhabits a rare space where art, ecology and social responsibility converge.

His relationship with art began not in galleries or exhibitions, but in a classroom. From his school days, drawing was not simply a subject but an instinct — a language through which he learned to observe, interpret and respond to the world around him. Under the guidance of two dedicated mentors, Ariyaratne Guru Mahathaya and Gunathilaka Guru Mahathaya, he honed both skill and discipline. Those early lessons laid the foundation for a lifelong engagement with visual storytelling.

“His work navigates between traditional Sinhala artistic sensibilities, abstract compositions and expansive landscapes.”

That commitment eventually materialised in two solo art exhibitions. The first, held in 2012, marked his formal entry into Sri Lanka’s art scene. The second, staged in Colombo in 2024, was a more mature statement — both in content and confidence. Featuring nearly fifty paintings, the exhibition drew an encouraging public response and reaffirmed his place as an artist with a distinct visual voice.

That commitment eventually materialised in two solo art exhibitions. The first, held in 2012, marked his formal entry into Sri Lanka’s art scene. The second, staged in Colombo in 2024, was a more mature statement — both in content and confidence. Featuring nearly fifty paintings, the exhibition drew an encouraging public response and reaffirmed his place as an artist with a distinct visual voice.

His work navigates between traditional Sinhala artistic sensibilities, abstract compositions and expansive landscapes. There is restraint in his use of form and colour, and an underlying dialogue between memory and space. Yet, despite positive reception, Halloluwa speaks candidly about the structural challenges faced by artists in Sri Lanka. Recognition remains limited; fair valuation even rarer.

“This is not merely an artistic issue,” he observes. “It is a social and economic problem.”

In Sri Lanka, art is often viewed through the lens of affordability rather than artistic merit. Many approach a painting by first calculating the contents of their wallet, not the value of the idea or labour behind it. In contrast, he notes, art in Europe and many other regions is treated as cultural capital — an investment in identity, history and thought. Until this mindset shifts, local artists will continue to struggle for sustainability.

The decisive push toward wildlife photography came from Professor Pujitha Wickramasinghe, a close friend who recognised both Halloluwa’s observational skills and his affinity with nature. From there, the journey deepened under the mentorship of senior wildlife photographer Ravindra Siriwardena.

Both mentors, he insists, deserve acknowledgment not merely as teachers but as ethical compasses. In a field increasingly driven by competition and spectacle, such grounding is invaluable.

Wildlife photography, Halloluwa argues, is among the most demanding visual disciplines. It cannot be improvised or rushed. “This is an art that demands restraint,” he says.

Among all subjects, elephants hold a special place in his work. Photographing elephants is not merely about proximity or scale, but about understanding behaviour. Observing social patterns, movement, mood and interaction transforms elephant photography into a constantly evolving challenge. It is precisely this complexity that draws him repeatedly to them.

Halloluwa is cautiously optimistic about the current surge of interest in wildlife photography among Sri Lankan youth. Opportunities have expanded, with local and international competitions, exhibitions and platforms becoming more accessible. However, he issues a clear warning: passion alone is not enough

Sri Lanka, he believes, is uniquely positioned in the global nature photography landscape. Few countries offer such concentrated biodiversity within a compact geographical area. This privilege, however, carries responsibility. Nature photography should not merely aestheticise wildlife, but foster respect, aware ness and conservation.

Parallel to his visual work runs another equally significant pursuit — environmental journalism. For the past seven to eight years, Halloluwa has worked as an independent environmental journalist, giving voice to ecological issues often sidelined in mainstream discourse. His entry into the field was guided by Thusara Gunaratne, whose encouragement he acknowledges with gratitude.

An old boy of D.S. Senanayake College, Colombo, Halloluwa holds a Diploma in Writing and Journalism from the University of Sri Jayewardenepura and has completed journalism studies at the Sri Lanka Press Institute. He is currently pursuing an Advanced Certificate in Wildlife Management and Conservation at the Open University of Sri Lanka — a testament to his belief that learning must remain continuous, especially in a rapidly changing ecological landscape.

Outside his professional life, he enjoys cricket, rugby and badminton. Yet even leisure intersects with responsibility. He is a founding member and former president of the D.S. Senanayake College Old Boys’ Wildlife Forum, an active member of Wild Tuskers Sri Lanka, and a contributor to several independent environmental and wildlife volunteer organisations. In an era dominated by speed, spectacle and short attention spans, Saman Halloluwa’s journey unfolds differently. It is deliberate, reflective and rooted in values. Through art, he captures memory and form. Through photography, he frames life beyond human control. Through journalism, he asks uncomfortable but necessary questions.

“What I do, what I love” is not fashion here.

It is conviction — patiently lived, quietly asserted, and urgently needed in a country still learning how to value its artists, its environment and its truth.

By Ifham Nizam ✍️

Life style

Shaping the future of style

Ramani Fernando Sunsilk Hair and Beauty Academy

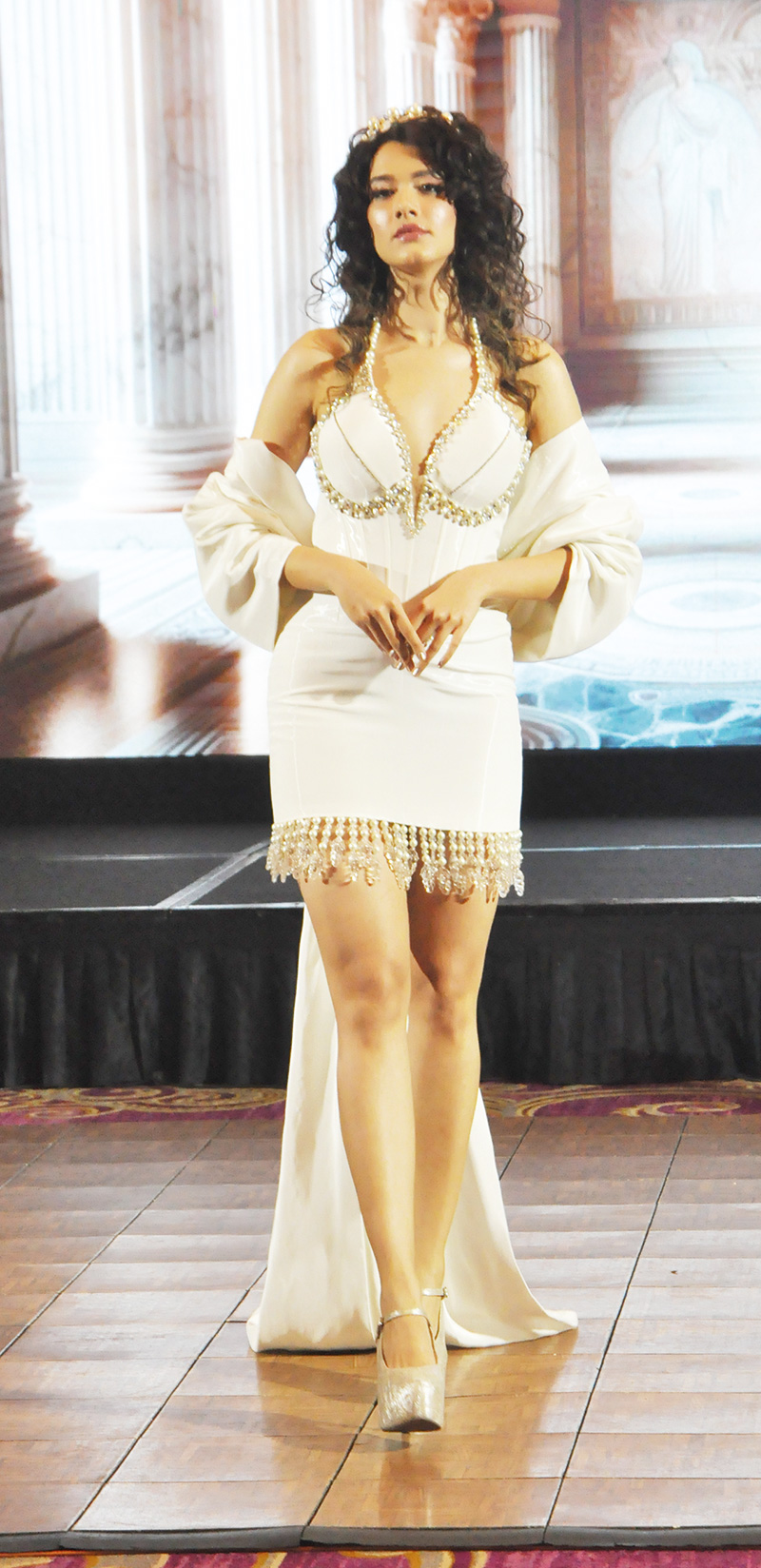

Ramani Fernando Sunsilk Hair and Beauty Academy marked their graduation of their latest cohort of aspiring hair professionals in a ceremony held at Kingsbury Hotel.

For over two decades, the Ramani Fernando Sunsilk Hair and Beauty Academy has stood as a beacon of excellence in beauty education in Sri Lanka. Founded by industry icon Ramani Fernando, the Academy has built a reputation for producing highly skilled professionals who go on to make their mark in salons, both locally and internationally. As the newly minted graduates step out into the world, they carry forward not just certificates, but also the promise of creative authority and personal empowerment.

The chief guest for the occasion was Rosy Senanayake, a long-standing supporter of the Academy’s mission. Addressing the graduates her message echoed her enduring belief that the beauty industry is not merely about aesthetic but about. confidence, self-worth and future leaders.

Over months of rigorous training, these young professionals honed their skills in cutting colouring, styling and contemporary artistry readying themselves to set trends rather than follow them.

Each graduate walked the stage with confidence, their dedication signalling a promising future for Sri Lanka’s beauty and fashion industry! With this new generation of stylists preparing to raise the standard of professional hairstyling.

Ramani Fernando, addressing the audience reflected on the academy’s mission to cultivate not only skills but vision and confidence in every student.

She urged the graduates to embrace continuous learning to take risks with creativity .The world of beauty is ever evolving, stay curious, stay bold and never underestimate the power of your talent, she added emphasising the importance of confidence, discipline and passion in carving a successful career in shaping the future of style.

These graduates are stepping into a world of endless possibilities. They are future of the country, who will carry a forward legacy of creativity. Behind every successful graduate at Sun silk Hair Academy stands a team dedicated to excellence. While Ramani Fernando serves as a visionary Principal and it is Lucky Lenagala, her trusted person who ensures that the academy runs seemingly.

From overseeing training sessions to guiding students, through hands on practice, Lucky plays a pivotal role in shaping the next generation of hairstylists.

Kumara de Silva, who has been the official compere Ramani’s, Hair graduation ceremony, from inception has brought energy, poise and professionalism. The Sunsilk Hair Academy is a celebration of talent and mentor ship for the graduates stepping confidentially into the next chapter of their careers, ready to make their mark on Sri Lanka beauty landscape

Pix by Thushara Attapathu

By Zanita Careem ✍️

Life style

Capturing the spirit of Christmas

During this season, Romesh Atapattu’s Capello Salon buzzes with a unique energy – a blend of festive excitement and elegance. Clients arrive with visions of holiday parties, office soirees, seeking looks that capture both glamour and individuality. The salon itself mirrors this celebrity mood. Warm lights, tasteful festive décor create an atmosphere where beauty and confidence flourish.

Romesh Atapattu himself curates the festive décor, infusing the space with his signature sense of style. His personal eye ensures that the décor complements the salon’s modern interiors.

As Colombo slips effortlessly into its most glamorous time of year, the Christmas season brings with it more than twinkling lights and celebrity soirees – it signals a transformation season at salons across the city. Capello salons are no exception.

At the heart of this festive beauty movement is Romesh Atapattu of Capello salons, a name synonymous with refined hair artistry, modern elegance and personalised style.

Christmas is about confidence and celebration. Romesh believes ‘People want to look their best without losing who they are”. Our role is to enhance, not overpower. This philosophy is evident in the salon’s seasonal approach.

Beyond trends, what sets Atapattu apart is the attention to individuality. Each consultation is treated as a creative collaboration – face shape, lifestyle, hair texture and personal style all play a role in creating the best for Romesh.

Stepping into Romesh’s salon during the Christmas season is an experience in itself. The space hums with festive energy while maintaining an atmosphere of calm sophistication.

The décor embraces the Christmas spirit with understated elegance. Tastefully adorned décor, beautiful Xmas tree, soft gold and ivory tones, and gentle hints of red are woven seamlessly into the salon’s contemporary design.

His staff, known for their warmth and professionalism also plays a key role in shaping the salon’s atmosphere—friendly, stylish and always welcoming. The Capello staff combine skill and creativity to deliver results that have a lasting impression.

Beyond trends, what sets Romesh Atapattu apart is the attention to individuality. Each consultation is treated as a creative collaboration – face shape, lifestyle, hair texture and personal style all play a role.

He is a professional who blends technical mastery with a deeply personal approach to style. His dedicated team of skilled professionals, operate with quiet confidence ensuring styles that create an atmosphere of trust, turning every appointment into a personalised and memorable experience.

(ZC) ✍️

Pic by Rohan Herath

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoGurusinha’s Boxing Day hundred celebrated in Melbourne

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoLeading the Nation’s Connectivity Recovery Amid Unprecedented Challenges

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoTime to close the Dickwella chapter

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoIt’s all over for Maxi Rozairo

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoEnvironmentalists warn Sri Lanka’s ecological safeguards are failing

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoDr. Bellana: “I was removed as NHSL Deputy Director for exposing Rs. 900 mn fraud”

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoDons on warpath over alleged undue interference in university governance

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoDigambaram draws a broad brush canvas of SL’s existing political situation