Features

St. Maximilian Kolbe:‘The Saint and Hero at Auschwitz’ and His Visits To Sri Lanka in the 1930s

Part II

St. Maximilian Kolbe’s Visits to Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and His Impressions

St. Maximian Kolbe, during his missionary travels to and from Japan, China and India, visted Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon) in 1930, 1932 and 1933. The impressions he formed during these visits as recorded in his contemporary writings – letters, diaries, notes and article, provide a fascinating read.

March 1930

Whilst in transit and staying aboard a ship anchored in the port of Colombo for two days in March 1930 (March 24-25), St. Maximilian Kolbe and his fellow missionaries, Br. Zygmunt and Br. Seweryn visited several notable locations in the city of Colombo. These included the Colombo Catholic Press, described by him as ‘the print shop of the Oblate Fathers of Mary Immaculate (OMI)’ which published “The Messenger of the Heart of Jesus” in English and Sinhalese; a leading Catholic school; St. Anthony’s Church, Kochchikade; and the Post Office to buy postcards. He also distributed the Miraculous Medals at the places he visited.

In his notes, he also makes mention of the tropical ‘summer heat’, ‘palm trees’ (a likely reference to the coconut trees), the sight of ‘a Buddhist monk’, ‘street cars’ (tram cars) and ‘cab drivers’ in Colombo. He attentively observed the devotional gestures of the faithful – ‘bowing’, ‘partly removing turbans’, ‘ joining hands’, ‘kneeling’, and placing ‘hands on the glass’ of the vitrine encasing the statue of St. Anthony whilst praying to him. He calls them ‘such good souls!’.

His notes of Tuesday, March 25, 1930 (Feast of the Annunciation of Most Holy Virgin Mary) record celebrating the ‘Mass and Communion according to the intentions of the Immaculate, and speaks of a late afternoon ‘typhoon’, ‘storm’ and rain, and of ‘jumping fish’ being ‘tossed here and there’. In a parting remark, he also recorded that he had got into the boat to return to the ship, leaving the city of Colombo, ‘taking along pleasant impressions.’

[Source: March 24,25 1930 Monday Tuesday – Ceylon, port [Colombo]: The Writings of St Maximilian Maria Kolbe, Volume II Various writings, nr 991 A, Daily Notes, Notebook IV (1930-1933)page 1713-1714 Nerbini International 2016]

Summer (June- July) 1932

In the summer of 1932, St. Maximilian Kolbe visited Sri Lanka twice on his travels to and from India, en route from Japan and Hong Kong. In a letter to his superior in Warsaw, he recorded:

‘On our way there we stopped in Hong Kong, where Fr. Wieczorek, a famous Salesian missionary, asked me why we were not establishing a Niepokalanów in China (in Hong Kong). We also stopped in Singapore, where the Fathers of the Congregation of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary pointed out a site in China where a Niepokalanów could be nestled, about an eight-hour train journey from Peking (which is not far, considering average distances in Asia).

‘From there, we then crossed the Indian Ocean up to Colombo, on the island of Ceylon, which had belonged to India in the past. The crossing was rather miserable, though. The winds, called “monsoon,” blew day and night, and the ship, apparently forgetful of its thousand-ton weight, listed horribly forward, backward, or sideways. Eventually, with a one day delay due to our struggle against the winds, we landed in Colombo, where I stayed a few days over at the Oblate Fathers of the Immaculata, who are involved in missionary work there. I intended to rest and re-gain my balance, to be ready to face the sweltering heat of train cars in the rays of the tropical sun.’

[ Source: Searching for a New Niepokalanow July 1932: The Writings of St Maximilian Maria Kolbe, Volume II Various Writings, No: 991 H, Daily Notes, Notebook IV (1930-1933)page 1737,1738, Nerbini International 2016

He rested for a few days at the House of the Oblate Fathers of the Immaculate in Colombo to regain his composure, before he travelled to Ernakulam in India by train. Commenting on the train journeys from Colombo to and from India, St. Maximilian wrote to Fr. Kornel Czupryk, his superior from Colombo on July 04, 1932:

‘The journey here and back by train I did in second class. For the outward leg, in fact, at the Cook agency, where I had bought the ticket, I was told that the third class is prohibited (for a European), although later I became convinced that it was possible; but not for the return, because otherwise, before leaving India to go onward to Ceylon, I would have had to spend a five-day quarantine period in a field in countryside, in the midst of other indigenous people who might be infected with infectious diseases (malaria, cholera, and the like). Just spending any time in a situation like that, in a warm, foreign climate would be more than enough to bring down some kind of illness on me. In addition, the cost of spending that time there. Instead, I could sleep during the night and was not quite so hot, because there were electric fans. I think even our own, at least at the beginning, must travel the great distances across India in second class.’ ….

‘Nevertheless the Immaculata, who had very lovingly assisted me all through my journey, helped me in this journey as well, so that my health was not made overly feeble over the day and two nights I spent on the train. The one thing I could not do was eat.’

‘A notice had been posted on train car doors warning against infectious diseas-es: malaria, cholera, etc. Also, I was beginning to ache here and there. What to do? At a station, I clung to hot coffee and drank: I swallowed quite a bit. It did me good. Then I threw out the “molangon”” (Indian fruit) to the monkeys that were roaming along the pavement, because I realized that that type of fruit did not agree with me. I trundled on, trying somehow to get to the end of the journey, to the town of Ernakulam, located in the Indian principality of Cochin, on the Malabar Coast.’

[Source: St. Maximilian Kolbe’ s Letter to Fr. Kornel Czupryk July 1, 1932 from Colombo: The Writings of St Maximilian Maria Kolbe, Volume I, Letters, nr 443, page 948, Nerbini International 2016]

Visit in September 1933

In 1933, he visited Sri Lanka for the third time, whilst in transit and staying aboard the ship, the Conte Rosso, anchored in the port of Colombo for about six hours. He gives a fascinating and vivid account of this brief visit in his article ‘ Colombo: Impressions of a Trip to the Mission of Japan’ published in Rycerz Niepokalanej, September, 1934, as follows:

‘Toward midday’ our ship Conte Rosso was nearing the port of Colombo, and at midday we could disembark. It was announced onboard that there would be meat for lunch, even though

it was Friday. Moreover, until the time of departure, at six, there was not much time; so,

having eaten some bread, cheese, and two green Indian oranges each, we went on land by

motorboat, paying half a Ceylonese rupee, and headed toward the city.’

‘First of all, we went, on the Borella tram, toward the episcopal palace. The conductor and the driver, thankful for the two medals of the Immaculata that we gave them, decided to drop us in front of the bishop’s palace. What good Hindus! The Immaculata will reward them for this. After visiting the small humble church situated beside the bishop’s house, we walked on foot along the paved road-full of spat-out gobs of red gum, which the inhabitants chew untiringly-toward the house of the Missionary Sisters of Mary, to procure some hosts and candles. Along the way, we walked in the cooling shade of the trees, since it was really hot. In front of us, a lot of shops with bananas of different colors and thickness, coconuts, and other tropical fruits.’

‘The small church of the sisters is very sweet, more so since Jesus, exposed all day long in the Blessed Sacrament, welcomes people all day long. Coming out of the church we found a girl who kindly invited us to go into the parlor. It was clear that our Franciscan habits, somewhat foreign to Ceylon, had already been noticed. On the principal wall of the parlor, Jesus looked down from the cross, whilst at his feet there was a big and beautiful picture of the Immaculata crushing the infernal serpent’s head with her immaculate foot. Evidently in the spirit of Niepokalanów.’

‘Soon after, two nuns dressed in white greeted us. They were the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary. The superior explained thoroughly that the aim of their institute is to go on mission in order to lead souls to Jesus, always through Mary, and that they belong to Mary, Mary is their Patroness and they are the property of Mary. She spoke to us about the numerous blessings bestowed by Mary,….’

‘We gladly accepted some soda water with ice: only he who travels in such tropical countries could appreciate its utility and value.’

‘In addition, we received both the hosts and candles; the sisters even wanted to take us to the ship, all this without our making any payment, for the sake of the Immaculata.’

‘Then, we again took the Fort tram to the last stop, at the harbor. Both the conductor and the driver accepted medals of the Immaculata. The tram driver explained to us that his conductor was Buddhist; however, his dark face, shining with joy, showed us that the medal would not go to waste.’

‘Here and there, the street was blocked by two-wheeled carts covered with a roof of palm leaves and drawn by small oxen with large humps. A large group of Hindu [in some places in his writings, St. Maximilian Kolbe refers to the native inhabitants of the Indian Subcontinent as’ Hindus’ not necessarily meaning their adherence to Hinduism] workers, dressed in a cloth that covered half of their bodies or in just a loincloth, was repairing a section of the tramline. Their dark bodies moved heavy picks. [Along the way we saw] the streets, always larger, the train station (from which we had left last year in search of the Indian Niepokalanów), and the harbor.’

[Visit to Nippon Restaurant – now Nippon Hotel]

‘We wanted, however, to visit also a Pole who had been residing there for a long time, Mr. Roszkowski, proprietor of the Nippon Restaurant. We left the harbor, therefore, turned right, and, after some minutes of walking in the midst of the continuous importuning of the merchants, we arrived at a row of small, waiting buses. We looked for one of the fullest-close, therefore, to departing-marked Slave Island, and we climbed up through the back door, into the middle of dark-skinned people, more or less dressed, residents of the area. Barefoot and indistinguishable from the other travelers, the conductor or the owner collected three cents from each person, and so, without losing time bothering with tickets, which in any case are a sign of mutual distrust, we get off in front of a recently constructed church, and from there, after barely 15 steps, we reach the Nippon Restaurant.’

Vases of flowers in front of the restaurant. We entered. On the wall, a picture of Our Lady of Częstochowa, and in front of it a small lamp; it was clear that it was the house of a Pole. Then, on top of a small cabinet, there was a statue of the Immaculata sent over from Niepokalanów: he was, therefore, also a reader of Rycerz. The proprietor was seated at a table and was finishing his midday “dinner” (the evening meal is called “supper”), a red dish of a gelatinous type. He immediately stood up: we greeted him and he invited us to eat with him. We drank coffee, ate some sweets, and lost ourselves in conversation. He tells us that he had just returned from hunting.

[When asked] “What kind of game is there in Ceylon?”

[Mr. Roszkowski, proprietor of the Nippon Restaurant had replied]:

“The most diverse. Yesterday evening, the house I was at, we captured a small boa in the kitchen. A boy crushed its head and it made such a noise. Fortunately, it was not a poisonous serpent. I gave it still alive to the Japanese consul. After four in the evening, the reptiles come out of their hiding places; they bask in the heat of the setting sun, and then in the dark of the night they go hunting. At dawn they again enjoy the warmth of the sun, until about eight, when the heat forces them to find shelter in the shady forests.

“In the evening or morning it is easy to spot crawling serpents in the countryside. Some time ago I saw a white serpent, a rarity; I was taking aim with my gun, but a Hindu put his hand on my arm, preventing me from shooting because it was a sacred serpent. There is also a great quantity of wild cats of several sizes: some lurk in the trees, leaping from high onto the necks of passers-by. There are also many bears, leopards, and antelopes. The proprietor of the reserve where I went some time ago to hunt had ordered a boy to bring down something heavier: so, he killed an enormous crocodile.”

‘We listened with astonishment to the stories of the old man, since we had never imagined the woods and shrubs we had so admired from the ship could hide so many dangerous surprises.’

‘Meanwhile, Mrs. Roszkowska, Japanese by birth, brought us a Japanese delicacy, “mochi” (pastries made of rice flour) with “hashi” (the chopsticks that Japanese use to eat). We greeted the lady and while we talked about religious matters regarding Japan, we ate some of those “mochi,” one of us two using the chopsticks, the other a fork.’

‘She thanked us in Japanese for Kishi, which pays her a visit every month. In this house, midway between the Polish Niepokalanów and the Japanese one, Polish Rycerz meets with Japanese Kishi every month. Only in the local language, does the Knight still not exist… May the Immaculata guide everything.’

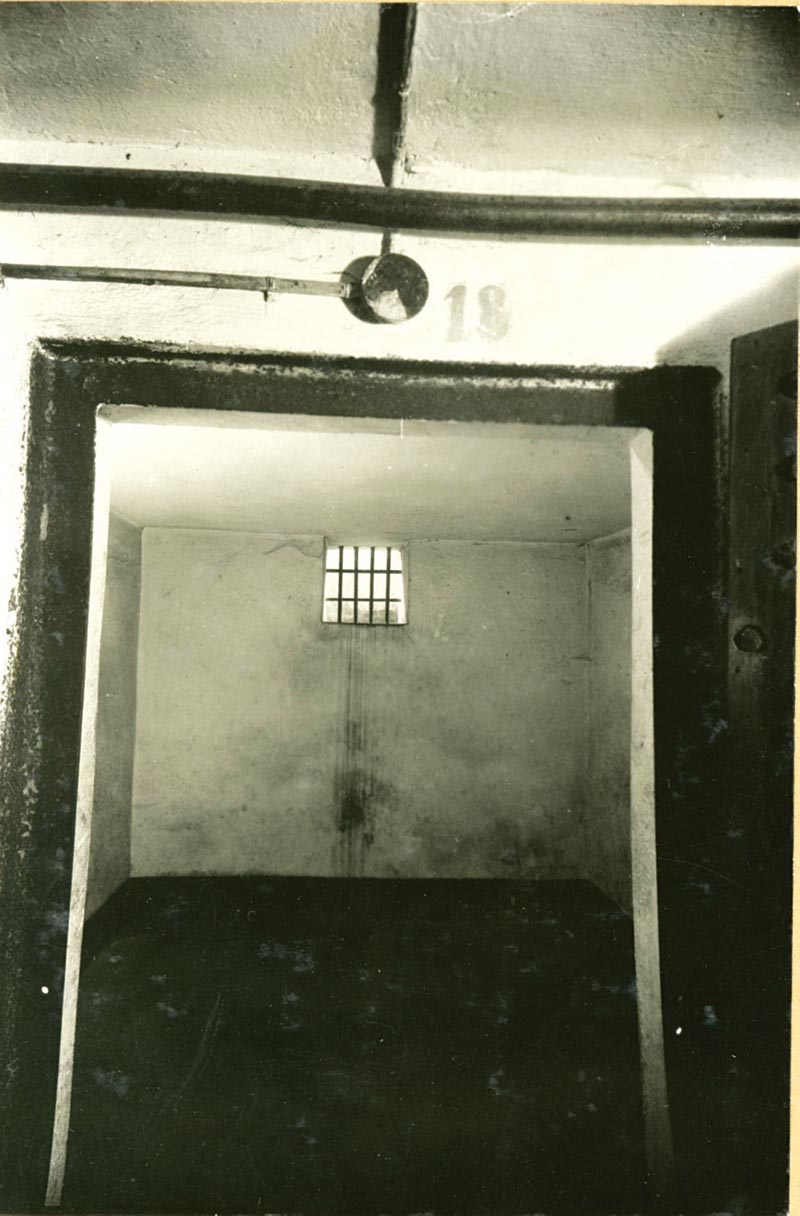

- Death Bunker at Auschwitz Photo courtesy: reproduced with the permission of The Archives of MI Niepokalanów (Archiwum MI Niepokalanów) , Teresin, Poland

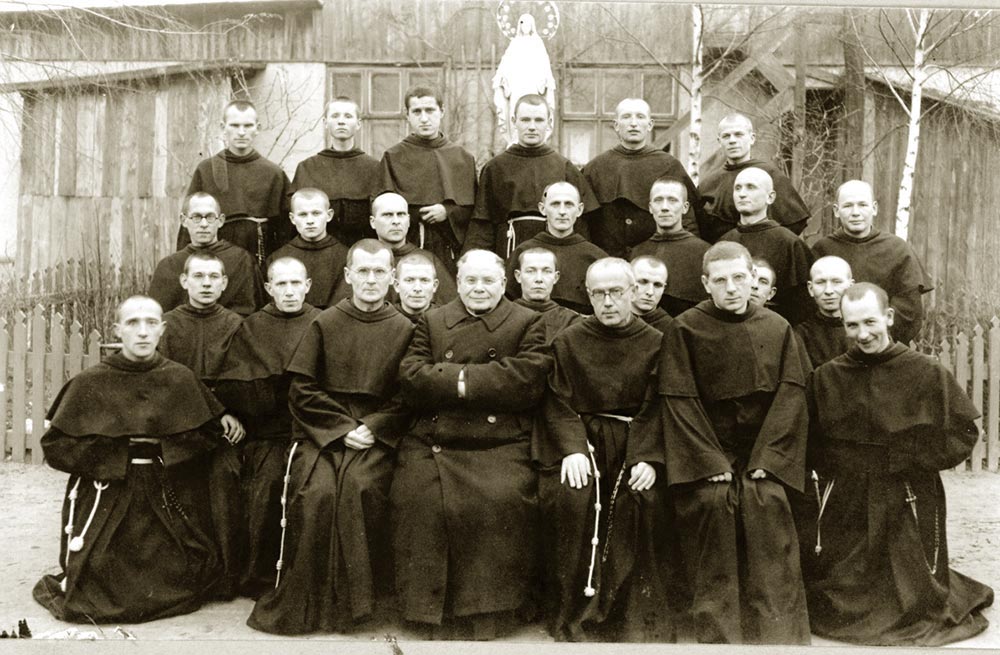

- St. Maximilian Kolbe in Nagasaki , Japan (1934) [St. Maximilian Kolbe [with his long beard] is seated in the mid dle Photo courtesy: reproduced with the permission of The Archives of MI Niepokalanów (Archiwum MI Niepokalanów) , Teresin, Poland

‘The Polish man and the Japanese lady said goodbye to us on the porch of the restaurant, while we left to make our way back to the harbor.’

‘On our way there, we entered the recently constructed church. It is absolutely beautiful and it is dedicated to the Blessed Mother. Then again to the bus. In the harbor zone, we come across our Polish crows-only they had forgotten how to croak.’

‘Immediately after, to the ship by motorboat. During the crossing, a Hindu, working as assistant on the boat, showed us some signs on the skin of his hand, which were supposed to mean that he belonged to the Catholic Church, and for this, he wanted… money. Poor con man, scrounger! These kinds were not lacking there either!’

‘At about six the ship moved out of the harbor, passing by the breakwater, pitching to the movement of the waves that hit uselessly against the barrier that prevented them from entering the harbor; foaming, they rose several meters high and broke and fell back into the sea, to rise immediately and hit again, and again, fall, breaking.’

‘The city lights grew fainter. Only the lighthouse still saluted us with its strong and intermittent streaks of light.’

[Source: The Writings of St Maximilian Maria Kolbe, Volume II, Articles, No: 1189, page 948, Nerbini International 2016 pp 2053- 2056]

Conclusion

When World War II broke out in 1939, St. Maximilian Kolbe was in charge of Niepokalanów. The Nazis invaded Poland. According to the Nazi doctrine, the Poles were racially inferior to the Germans. In their invasion of Poland, Nazi forces launched mass killing operations against the Polish civilians and intelligentsia. Upon capturing Poland, the Nazis took over the Polish banks, businesses and properties. They forced about 1. 7 million Poles out of their homes. The Nazi forces soon took control of Niepokalanów, and used it as a temporary internment camp for 3,500 Poles forcibly displaced by them.[ the photograph of the Nazi Officers which appeared in first part of this article in last Sunday’ s issue of this newspaper was a photograph taken in front of Niepokalanów].

Nazis first arrested St. Maximillian Kolbe in September 1939, and released him in December, 1939. He refused to sign the Nazi declaration Deutsche Volksliste, which would have granted him rights similar to those of German citizens. His family name ‘ Kolbe ‘ sounded German (though he was not an ethnic German), and he was fluent in the German language. Upon his release, St. Maximilian Kolbe resumed his work at his monastery at Niepokalanów. He received limited permission from the Nazis to continue publishing religious literature, albeit on a significantly reduced scale.

Some of the articles published in the publications of Niepokalanów were critical of the Nazi regime and its activities. On February 17, 1941, St. Maximilian and four other friars were arrested. On May 28, 1941, they transferred him to Auschwitz as prisoner 16670, where he died on August 14, 1941 in the supremely heroic act of love and sacrifice to save the life of a fellow prisoner as we already read in the first few paragraphs of this article.

His vision for India which also included Sri Lanka began to be realised 50 years later in 1980, when at the invitation of the Bishop of Kanjirappally (Syro-Malabar rite), OFM Conventual friars from Malta arrived in Kerala to establish the Order in India. At the 2007 General Chapter, the work of the mission in India was elevated to the administrative status of a Province (Province of St. Maximilian M. Kolbe in India). The work of the Province, in addition to its work in Kerala, today, comprises a Delegation in Andhrapradesh-Telengana (the Delegation of St. Joseph of Cupertino), a mission in Calcutta and another mission in Sri Lanka. Currently under its jurisdiction, there are 123 solemnly professed friars, 58 simply professed friars, 17 friaries and seven filial houses. In Sri Lanka, the Order of Friars Minor Convectual has four friaries in Katana, Battaramulla, Kandy and Jaffna and two Minor Seminaries.

The Militia of the Immaculata which St. Maximilian, founded in 1917 with six other friars, has spread throughout the world. It is today present on five continents and in 46 nations with a membership of around four million. It received its first official approval from the Church in 1922. On October 16, 1997, the Holy See erected it as an International Public Association of the Faithful. The MI International Centre has its headquarters in Rome, Italy. Its membership is open to the clergy, consecrated and laity. Whilst prayer is its main weapon in the spiritual battle with evil, members of the Militia Immaculata ‘also immerse themselves in apostolic initiatives throughout society, either individually or in groups, to deepen the knowledge of the Gospel and Christian Faith in them and in others.’ St. Mother Teresa of Calcutta was among its notable Knights of the Immaculata (as its members are called)

In Sri Lanka, there is one church consecrated to St. Maximilian Kolbe at Vishaka Watta in Ja Ela

[Acknowledgement: The writer expresses his sincere gratitude to Fr. Krzys Flis, Editor of Rycerz Niepokalanej, MI Niepokalanów, in Teresin, Poland and Miss Annamaria Mix, Archivist, Archiwum, MI Niepokalanów, Teresin, Poland for providing him with access to the writings of St.Maximilian Kolbe relating to his visits to Sri Lanka and the photographs with permission for reproduction]

By Prabhath de Silva ✍️

Features

Sustaining good governance requires good systems

A prominent feature of the first year of the NPP government is that it has not engaged in the institutional reforms which was expected of it. This observation comes in the context of the extraordinary mandate with which the government was elected and the high expectations that accompanied its rise to power. When in opposition and in its election manifesto, the JVP and NPP took a prominent role in advocating good governance systems for the country. They insisted on constitutional reform that included the abolition of the executive presidency and the concentration of power it epitomises, the strengthening of independent institutions that overlook key state institutions such as the judiciary, public service and police, and the reform or repeal of repressive laws such as the PTA and the Online Safety Act.

The transformation of a political party that averaged between three to five percent of the popular vote into one that currently forms the government with a two thirds majority in parliament is a testament to the faith that the general population placed in the JVP/ NPP combine. This faith was the outcome of more than three decades of disciplined conduct in the aftermath of the bitter experience of the 1988 to 1990 period of JVP insurrection. The manner in which the handful of JVP parliamentarians engaged in debate with well researched critiques of government policy and actions, and their service in times of disaster such as the tsunami of 2004 won them the trust of the people. This faith was bolstered by the Aragalaya movement which galvanized the citizens against the ruling elites of the past.

In this context, the long delay to repeal the Prevention of Terrorism Act which has earned notoriety for its abuse especially against ethnic and religious minorities, has been a disappointment to those who value human rights. So has been the delay in appointing an Auditor General, so important in ensuring accountability for the money expended by the state. The PTA has a long history of being used without restraint against those deemed to be anti-state which, ironically enough, included the JVP in the period 1988 to 1990. The draft Protection of the State from Terrorism Act (PSTA), published in December 2025, is the latest attempt to repeal and replace the PTA. Unfortunately, the PSTA largely replicates the structure, logic and dangers of previous failed counter terrorism bills, including the Counter Terrorism Act of 2018 and the Anti Terrorism Act proposed in 2023.

Misguided Assumption

Despite its stated commitment to rule of law and fundamental rights, the draft PTSA reproduces many of the core defects of the PTA. In a preliminary statement, the Centre for Policy Alternatives has observed among other things that “if there is a Detention Order made against the person, then in combination, the period of remand and detention can extend up to two years. This means that a person can languish in detention for up to two years without being charged with a crime. Such a long period again raises questions of the power of the State to target individuals, exacerbated by Sri Lanka’s history of long periods of remand and detention, which has contributed to abuse and violence.” Human Rights lawyer Ermiza Tegal has warned against the broad definition of terrorism under the proposed law: “The definition empowers state officials to term acts of dissent and civil disobedience as ‘terrorism’ and will lawfully permit disproportionate and excessive responses.” The legitimate and peaceful protests against abuse of power by the authorities cannot be classified as acts of terror.

The willingness to retain such powers reflects the surmise that the government feels that keeping in place the structures that come from the past is to their benefit, as they can utilise those powers in a crisis. Due to the strict discipline that exists within the JVP/NPP at this time there may be an assumption that those the party appoints will not abuse their trust. However, the country’s experience with draconian laws designed for exceptional circumstances demonstrates that they tend to become tools of routine governance. On the plus side, the government has given two months for public comment which will become meaningful if the inputs from civil society actors are taken into consideration.

Worldwide experience has repeatedly demonstrated that integrity at the level of individual leaders, while necessary, is not sufficient to guarantee good governance over time. This is where the absence of institutional reform becomes significant. The aftermath of Cyclone Ditwah in particular has necessitated massive procurements of emergency relief which have to be disbursed at maximum speed. There are also significant amounts of foreign aid flowing into the country to help it deal with the relief and recovery phase. There are protocols in place that need to be followed and monitored so that a fiasco like the disappearance of tsunami aid in 2004 does not recur. To the government’s credit there are no such allegations at the present time. But precautions need to be in place, and those precautions depend less on trust in individuals than on the strength and independence of oversight institutions.

Inappropriate Appointments

It is in this context that the government’s efforts to appoint its own preferred nominees to the Auditor General’s Department has also come as a disappointment to civil society groups. The unsuitability of the latest presidential nominee has given rise to the surmise that this nomination was a time buying exercise to make an acting appointment. For the fourth time, the Constitutional Council refused to accept the president’s nominee. The term of the three independent civil society members of the Constitutional Council ends in January which would give the government the opportunity to appoint three new members of its choice and get its way in the future.

The failure to appoint a permanent Auditor General has created an institutional vacuum at a critical moment. The Auditor General acts as a watchdog, ensuring effective service delivery promoting integrity in public administration and providing an independent review of the performance and accountability. Transparency International has observed “The sequence of events following the retirement of the previous Auditor General points to a broader political inertia and a governance failure. Despite the clear constitutional importance of the role, the appointment process has remained protracted and opaque, raising serious questions about political will and commitment to accountability.”

It would appear that the government leadership takes the position they have been given the mandate to govern the country which requires implementation by those they have confidence in. This may explain their approach to the appointment (or non-appointment) at this time of the Auditor General. Yet this approach carries risks. Institutions are designed to function beyond the lifespan of any one government and to protect the public interest even when those in power are tempted to act otherwise. The challenge and opportunity for the NPP government is to safeguard independent institutions and enact just laws, so that the promise of system change endures beyond personalities and political cycles.

by Jehan Perera

Features

General education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

A new batch arrived at our Faculty again. Students representing almost all districts of the country remind me once again of the wonderful opportunity we have for promoting social and ethnic cohesion at our universities. Sadly, however, many students do not interact with each other during the first few semesters, not only because they do not speak each other’s language(s), but also because of the fear and distrust that still prevails among communities in our society.

General education reform presents an opportunity to explore ways to promote social and ethnic cohesion. A school curriculum could foster shared values, empathy, and critical thinking, through social studies and civics education, implement inclusive language policies, and raise critical awareness about our collective histories. Yet, the government’s new policy document, Transforming General Education in Sri Lanka 2025, leaves us little to look forward to in this regard.

The policy document points to several “salient” features within it, including: 1) a school credit system to quantify learning; 2) module-based formative and summative assessments to replace end-of-term tests; 3) skills assessment in Grade 9 consisting of a ‘literacy and numeracy test’ and a ‘career interest test’; 4) a comprehensive GPA-based reporting system spanning the various phases of education; 5) blended learning that combines online with classroom teaching; 6) learning units to guide students to select their preferred career pathways; 7) technology modules; 8) innovation labs; and 9) Early Childhood Education (ECE). Notably, social and ethnic cohesion does not appear in this list. Here, I explore how the proposed curriculum reforms align (or do not align) with the NPP’s pledge to inculcate “[s]afety, mutual understanding, trust and rights of all ethnicities and religious groups” (p.127), in their 2024 Election Manifesto.

Language/ethnicity in the present curriculum

The civil war ended over 15 years ago, but our general education system has done little to bring ethnic communities together. In fact, most students still cannot speak in the “second national language” (SNL) and textbooks continue to reinforce negative stereotyping of ethnic minorities, while leaving out crucial elements of our post-independence history.

Although SNL has been a compulsory subject since the 1990s, the hours dedicated to SNL are few, curricula poorly developed, and trained teachers few (Perera, 2025). Perhaps due to unconscious bias and for ideological reasons, SNL is not valued by parents and school communities more broadly. Most students, who enter our Faculty, only have basic reading/writing skills in SNL, apart from the few Muslim and Tamil students who schooled outside the North and the East; they pick up SNL by virtue of their environment, not the school curriculum.

Regardless of ethnic background, most undergraduates seem to be ignorant about crucial aspects of our country’s history of ethnic conflict. The Grade 11 history textbook, which contains the only chapter on the post-independence period, does not mention the civil war or the events that led up to it. While the textbook valourises ‘Sinhala Only’ as an anti-colonial policy (p.11), the material covering the period thereafter fails to mention the anti-Tamil riots, rise of rebel groups, escalation of civil war, and JVP insurrections. The words “Tamil” and “Muslim” appear most frequently in the chapter, ‘National Renaissance,’ which cursorily mentions “Sinhalese-Muslim riots” vis-à-vis the Temperance Movement (p.57). The disenfranchisement of the Malaiyaha Tamils and their history are completely left out.

Given the horrifying experiences of war and exclusion experienced by many of our peoples since independence, and because most students still learn in mono-ethnic schools having little interaction with the ‘Other’, it is not surprising that our undergraduates find it difficult to mix across language and ethnic communities. This environment also creates fertile ground for polarizing discourses that further divide and segregate students once they enter university.

More of the same?

How does Transforming General Education seek to address these problems? The introduction begins on a positive note: “The proposed reforms will create citizens with a critical consciousness who will respect and appreciate the diversity they see around them, along the lines of ethnicity, religion, gender, disability, and other areas of difference” (p.1). Although National Education Goal no. 8 somewhat problematically aims to “Develop a patriotic Sri Lankan citizen fostering national cohesion, national integrity, and national unity while respecting cultural diversity (p. 2), the curriculum reforms aim to embed values of “equity, inclusivity, and social justice” (p. 9) through education. Such buzzwords appear through the introduction, but are not reflected in the reforms.

Learning SNL is promoted under Language and Literacy (Learning Area no. 1) as “a critical means of reconciliation and co-existence”, but the number of hours assigned to SNL are minimal. For instance, at primary level (Grades 1 to 5), only 0.3 to 1 hour is allocated to SNL per week. Meanwhile, at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), out of 35 credits (30 credits across 15 essential subjects that include SNL, history and civics; 3 credits of further learning modules; and 2 credits of transversal skills modules (p. 13, pp.18-19), SNL receives 1 credit (10 hours) per term. Like other essential subjects, SNL is to be assessed through formative and summative assessments within modules. As details of the Grade 9 skills assessment are not provided in the document, it is unclear whether SNL assessments will be included in the ‘Literacy and numeracy test’. At senior secondary level – phase 1 (Grades 10-11 – O/L equivalent), SNL is listed as an elective.

Refreshingly, the policy document does acknowledge the detrimental effects of funding cuts in the humanities and social sciences, and highlights their importance for creating knowledge that could help to “eradicate socioeconomic divisions and inequalities” (p.5-6). It goes on to point to the salience of the Humanities and Social Sciences Education under Learning Area no. 6 (p.12):

“Humanities and Social Sciences education is vital for students to develop as well as critique various forms of identities so that they have an awareness of their role in their immediate communities and nation. Such awareness will allow them to contribute towards the strengthening of democracy and intercommunal dialogue, which is necessary for peace and reconciliation. Furthermore, a strong grounding in the Humanities and Social Sciences will lead to equity and social justice concerning caste, disability, gender, and other features of social stratification.”

Sadly, the seemingly progressive philosophy guiding has not moulded the new curriculum. Subjects that could potentially address social/ethnic cohesion, such as environmental studies, history and civics, are not listed as learning areas at the primary level. History is allocated 20 hours (2 credits) across four years at junior secondary level (Grades 6 to 9), while only 10 hours (1 credit) are allocated to civics. Meanwhile, at the O/L, students will learn 5 compulsory subjects (Mother Tongue, English, Mathematics, Science, and Religion and Value Education), and 2 electives—SNL, history and civics are bunched together with the likes of entrepreneurship here. Unlike the compulsory subjects, which are allocated 140 hours (14 credits or 70 hours each) across two years, those who opt for history or civics as electives would only have 20 hours (2 credits) of learning in each. A further 14 credits per term are for further learning modules, which will allow students to explore their interests before committing to a A/L stream or career path.

With the distribution of credits across a large number of subjects, and the few credits available for SNL, history and civics, social/ethnic cohesion will likely remain on the back burner. It appears to be neglected at primary level, is dealt sparingly at junior secondary level, and relegated to electives in senior years. This means that students will be able to progress through their entire school years, like we did, with very basic competencies in SNL and little understanding of history.

Going forward

Whether the students who experience this curriculum will be able to “resist and respond to hegemonic, divisive forces that pose a threat to social harmony and multicultural coexistence” (p.9) as anticipated in the policy, is questionable. Education policymakers and others must call for more attention to social and ethnic cohesion in the curriculum. However, changes to the curriculum would only be meaningful if accompanied by constitutional reform, abolition of policies, such as the Prevention of Terrorism Act (and its proxies), and other political changes.

For now, our school system remains divided by ethnicity and religion. Research from conflict-ridden societies suggests that lack of intercultural exposure in mono-ethnic schools leads to ignorance, prejudice, and polarized positions on politics and national identity. While such problems must be addressed in broader education reform efforts that also safeguard minority identities, the new curriculum revision presents an opportune moment to move this agenda forward.

(Ramya Kumar is attached to the Department of Community and Family Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, University of Jaffna).

Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.

by Ramya Kumar

Features

Top 10 Most Popular Festive Songs

Certain songs become ever-present every December, and with Christmas just two days away, I thought of highlighting the Top 10 Most Popular Festive Songs.

The famous festive songs usually feature timeless classics like ‘White Christmas,’ ‘Silent Night,’ and ‘Jingle Bells,’ alongside modern staples like Mariah Carey’s ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You,’ Wham’s ‘Last Christmas,’ and Brenda Lee’s ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree.’

The following renowned Christmas songs are celebrated for their lasting impact and festive spirit:

* ‘White Christmas’ — Bing Crosby

The most famous holiday song ever recorded, with estimated worldwide sales exceeding 50 million copies. It remains the best-selling single of all time.

* ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’ — Mariah Carey

A modern anthem that dominates global charts every December. As of late 2025, it holds an 18x Platinum certification in the US and is often ranked as the No. 1 popular holiday track.

Mariah Carey: ‘All I Want for Christmas Is You’

* ‘Silent Night’ — Traditional

Widely considered the quintessential Christmas carol, it is valued for its peaceful melody and has been recorded by hundreds of artistes, most famously by Bing Crosby.

* ‘Jingle Bells’ — Traditional

One of the most universally recognised and widely sung songs globally, making it a staple for children and festive gatherings.

* ‘Rockin’ Around the Christmas Tree’ — Brenda Lee

Recorded when Lee was just 13, this rock ‘n’ roll favourite has seen a massive resurgence in the 2020s, often rivaling Mariah Carey for the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100.

* ‘Last Christmas’ — Wham!

A bittersweet ’80s pop classic that has spent decades in the top 10 during the holiday season. It recently achieved 7x Platinum status in the UK.

* ‘Jingle Bell Rock’ — Bobby Helms

A festive rockabilly standard released in 1957 that remains a staple of holiday radio and playlists.

* ‘The Christmas Song (Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire)’— Nat King Cole

Known for its smooth, warm vocals, this track is frequently cited as the ultimate Christmas jazz standard.

Wham! ‘Last Christmas’

* ‘It’s the Most Wonderful Time of the Year’ — Andy Williams

Released in 1963, this high-energy big band track is famous for capturing the “hectic merriment” of the season.

* ‘Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer’ — Gene Autry

A beloved narrative song that has sold approximately 25 million copies worldwide, cementing the character’s place in Christmas folklore.

Other perennial favourites often in the mix:

* ‘Feliz Navidad’ – José Feliciano

* ‘A Holly Jolly Christmas’ – Burl Ives

* ‘Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow!’ – Frank Sinatra

Let me also add that this Thursday’s ‘SceneAround’ feature (25th December) will be a Christmas edition, highlighting special Christmas and New Year messages put together by well-known personalities for readers of The Island.

-

News23 hours ago

News23 hours agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

Midweek Review7 days ago

Midweek Review7 days agoHow massive Akuregoda defence complex was built with proceeds from sale of Galle Face land to Shangri-La

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPope fires broadside: ‘The Holy See won’t be a silent bystander to the grave disparities, injustices, and fundamental human rights violations’

-

News6 days ago

News6 days agoPakistan hands over 200 tonnes of humanitarian aid to Lanka

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoUnlocking Sri Lanka’s hidden wealth: A $2 billion mineral opportunity awaits

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoBurnt elephant dies after delayed rescue; activists demand arrests

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoColombo Port facing strategic neglect

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoArmy engineers set up new Nayaru emergency bridge