Sat Mag

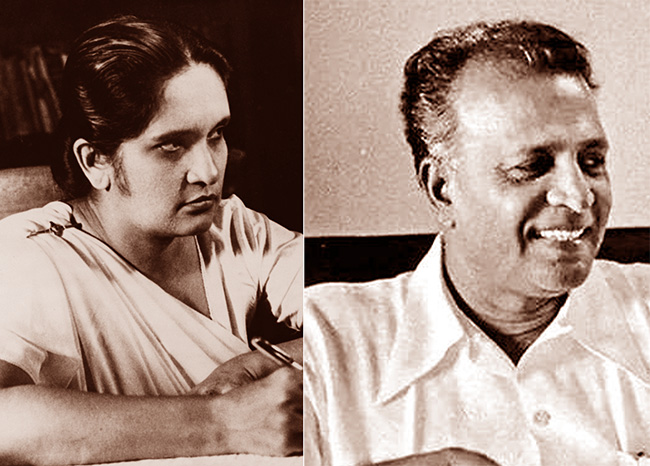

Sri Lanka’s foreign policy formulation: The first 10 years

By Uditha Devapriya

The foreign policy followed by Sri Lanka in its first few years of independence was largely determined by two factors: its proximity to India and its colonial past. The one influenced the other. The nature of Sri Lanka’s colonial bourgeoisie, who became the legatees of power once the British “left”, and their ideological orientation, had a say as well. The conflux of these factors has led several commentators, Marxist or otherwise, to argue that Sri Lanka’s foreign policy was structured along elitist, pro-Western lines. Among the reasons cited for this view are the close links between Colombo and London that survived independence, as seen in the Defence, External Affairs, and Public Officers’ Agreements of 1947.

Those who disfavour this theory contend, or imply, that Sri Lanka did not have the luxury of shaping a policy of its own. The decision to favour an extra-regional power, Britain, over its most immediate neighbours had much to do with the perception of threats from India, the de facto superpower in the subcontinent. The External Affairs Ministry, by dint of the 1947 Constitution placed in the jurisdiction of the Prime Minister, had no policy it could evolve on its own; this partly explains why Sri Lanka remained the only Commonwealth country with no Institute of International Affairs until 1959. Obviously, its geographical position would have had a say there. But that couldn’t have been the only factor.

By 1947, the political power in Sri Lanka had come to be dominated by a plantation rentier elite. As George Beckford in his extensive study of plantation economies, Persistent Poverty, put it, such elites preferred constitutional reform over political protest to secure independence. This was borne out by the kind of economy they were exercising their political power within; more so than its immediate neighbours, Sri Lanka fit the stereotype of a classic dependent colony, with primitive export-oriented plantation enclaves on the one hand and a backward subsistence peasant economy on the other.

A dependent colony produces a dependent elite. How dependent the elite were can best be seen in the way in which they secured independence: through constitutional cosmetics and formal requests, rather than the Indian strategy of non-violent action. The ideology of this elite naturally influenced the formulation of foreign policy by the so-called “triumvirate”: D. S. Senanayake, Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, and Sir Ivor Jennings. Of course, to say that foreign policy was a mere extension of such ideological imperatives would be to simplify matters, since domestic policy is not and cannot be allowed to monopolise external affairs. And yet it did play a role, a pivotal one.

Senanayake’s preference for a West-aligned foreign policy as opposed to a neutral one – at a time when the idea of a Non-Aligned Movement was still years if not a good decade away – led him to consistently emphasise on the limits imposed on Sri Lanka’s sovereignty by its geographical position in his despatches to Whitehall, during negotiations for independence. In fact, reflecting this, Andrew Caldecott’s and Geoffrey Layton’s proposals on constitutional reforms in 1943, the Ministers’ Draft Constitution in 1944, and the Soulbury Constitution all reserved to the UK the twin matters of defence and external affairs: areas which would be most affected by the geopolitical implications of that geographical position.

Senanayake’s preference for a West-aligned foreign policy as opposed to a neutral one – at a time when the idea of a Non-Aligned Movement was still years if not a good decade away – led him to consistently emphasise on the limits imposed on Sri Lanka’s sovereignty by its geographical position in his despatches to Whitehall, during negotiations for independence. In fact, reflecting this, Andrew Caldecott’s and Geoffrey Layton’s proposals on constitutional reforms in 1943, the Ministers’ Draft Constitution in 1944, and the Soulbury Constitution all reserved to the UK the twin matters of defence and external affairs: areas which would be most affected by the geopolitical implications of that geographical position.

Historians are divided on why these matters were willingly conceded to Whitehall by the government. K. M. de Silva, for instance, contends that notwithstanding the British-inclined nature of these pacts, they were devised by Senanayake’s advisers “as a pragmatic solution to a complex problem.” “Pragmatic” is, to be sure, a word shrouded in ambiguity; to me, what was “pragmatic” about the agreements was that they cohered with the anti-Marxist ideology of most of those who belonged to the ruling party, the UNP.

The threat of India did seem real, at the time. But – and this is a point ignored by those who excoriate Senanayake as well as by those who exonerate him – that threat was, while not imagined (even in as early as 1944 Nehru had made alarming statements about Sri Lanka’s closeness to India), overtly interpreted in terms of its impact on a colonised elite which had less in common with the new India than with the old British Empire. Senanayake and his colleagues fitted the mould of a Hastings Banda rather than a Nehru or a Gandhi, or even a Jomo Kenyatta, here, owing to the quickness with which they aligned with the Western bloc over even the Non Aligned Movement. This underpins my counterargument to de Silva’s pragmatist reading of Senanayake’s foreign policy: that it was a macrocosm of his party’s pro-Western outlook, and that it stemmed from the recognition of a need to maintain the stronghold of a compradore elite through friendly relations with the West.

The counterargument to this counterargument is that the UNP never actively pursued a pro-Western policy at the cost of cordial relations with other countries. Proponents of this school of thought point at an address given by Senanayake in 1951 to the BBC regarding a “middle way” between Western and Eastern blocs, the Rubber-Rice Pact signed a year or so later with China despite opposition from more rightwing elements within the UNP, and the establishment of trade links with the Iron Curtain under the fanatically anticommunist John Kotelawala. Historians also point at the refusal of the Senanayake government to allow the Dutch military to use the country’s aerodromes in their assault on Indonesian nationalists as another example of how pragmatic diplomatic initiative, rather than crude political ideology, shaped its relations with the rest of the world.

Two points need to be borne in mind when making these arguments. The first is that while opposition to Marxism didn’t really prevail over all other considerations in foreign policy, it nevertheless had a large say. Only when pressing economic imperatives dictated otherwise did UNP governments, particularly under the Senanayakes (who were much less daunted by the prospect of trade with Communists than either J. R. Jayewardene or John Kotelawala), consider risking the hostility of the Western bloc, if despite that risk substantial or urgently needed economic benefits could be reaped. The Rubber-Rice Pact in that sense signalled not only the futility of hanging on to the US as a fair weather friend – after all it refused to buy our rubber at higher prices and then, when the country had nowhere else to go, threatened sanctions if it negotiated with Peking – but also the necessity of forging links with other countries, a necessity recognised in full by all three Bandaranaike-led SLFP regimes. In other words, the UNP drew a distinction between trade and diplomacy, a futile and unsustainable dichotomy that reached its fullest expression when the John Kotelawala regime established trade links with the Soviet Union without opening a single embassy.

The second point, a corollary from the first, is that even though UNP regimes espoused a “middle path”, anticipating the Non-Aligned Movement long before it came into being, they did so while acknowledging the West as their ideological ally. It remains to be seen what the two Senanayakes would have done at Bandung had they been in power, but we know from archival material that both Jayewardene and Kotelawala favoured an anticommunist line as far as NAM was concerned. Kotelawala, in fact, proved to be the thorn in the side of India’s leadership over the subcontinent, something that surfaced only too clearly when he began entertaining notions of joining the US-allied SEATO (a prospect dreaded by Nehru) in a bid to get economic aid from Washington, and indicted “Soviet colonialism” in his opening speech at the Bandung Conference (which upset both Nehru and Zhou Enlai).

Even in its steadfast and laudable refusal to let the Dutch military use the country’s airspace against Indonesia, the Senanayake government paid as much obeisance to the necessity of maintaining relations with a sovereign State that happened to supply the country with some much needed commodities as it did to the reality of dwindling Dutch influence in the region, a reality underscored by the countervailing influence of US officials which compelled Dutch authorities to stop the attacks. The US did to the Dutch what it would do to Britain in 1956 during the Suez Crisis; thus when the UNP’s mantle passed to the Kotelawala-Jayewardene wing, the pro-West outlook of the party shifted from Whitehall to Washington.

Even in its steadfast and laudable refusal to let the Dutch military use the country’s airspace against Indonesia, the Senanayake government paid as much obeisance to the necessity of maintaining relations with a sovereign State that happened to supply the country with some much needed commodities as it did to the reality of dwindling Dutch influence in the region, a reality underscored by the countervailing influence of US officials which compelled Dutch authorities to stop the attacks. The US did to the Dutch what it would do to Britain in 1956 during the Suez Crisis; thus when the UNP’s mantle passed to the Kotelawala-Jayewardene wing, the pro-West outlook of the party shifted from Whitehall to Washington.

At any rate, no one who has read up on the McCarthyist tactics of the UNP from this period, culminating in the deportation of Rhoda Miller de Silva and the “China in Trinco” scare in the last years of the first Sirimavo Bandaranaike regime, would deny that at its most avowedly neutral, all UNP governments until 1989 believed in alignment with a US-led Cold War front. This explains why the Senanayake government, while turning down the Dutch, allowed a US flotilla (comprising four destroyers and a light cruiser) to use the harbour on its way to the Korean War, even though that War had become a UN matter and Sri Lanka was yet to join the UN, and India and Pakistan had both decided not to get involved in it. Over time this became a contradiction: as D. M. Prasad noted, UNP regimes “inclined towards the West in spite of their desire to keep Ceylon aloof from the tension of the Cold War.” It was a classic case of too many eggs and too few baskets.

Indeed, Senanayake’s denunciations of Communism, of Russia and China, tell us plainly that as with relations with these countries, their stance on and attitude to India was shaped by their alignment with the West. The biggest source of anxiety for India from Sri Lanka, in its first few years of independence, had been the Senanayake regime’s act of disenfranchising estate Tamils, which it had enforced to derail the Left. Yet it did nothing. It’s pertinent to recall here that 40 years later, when J. R. Jayewardene rebuffed Rajiv Gandhi (in the face of a weakening Non-Aligned Movement and thawing relations between the West and the Iron Curtain) using the Western bloc as a backup, it led to disastrous results; that fiasco finally proved the folly of the political right’s alienation of India. Moreover as Rosemary Brissenden aptly noted in a 1960 essay, UNP regimes “felt themselves bound” by what that country did, to the extent that they came to fear “the disruptive power” of estate Tamils and labourers. The truth was that not even the most reactionary political elements could afford to sideline these matters. If they did, it was to their own peril.

The UNP had fears about Indian expansionism which emerged from statements made by not just heads of state, but also academics. K. M. Panikkar, for instance, put forward his idea of “strategic unity” with Sri Lanka and Myanmar for a realistic foreign policy underlying India’s national defence priorities, contending that the Indian Ocean should “remain truly Indian”, while K. B. Vaidya proposed a federation with Sri Lanka and Myanmar. The most alarming statements issued, naturally, from the great Nehru, though as scholars have pointed out he made those assertions – that a small state “may survive as a culturally autonomous area but not as an independent political unit”, and that Sri Lanka could become “an autonomous unit of the Indian federation” – before the country gained independence. Certain writers tend to view these remarks differently, as I do: for them and for me, they signalled India’s desire to escape the Western sphere of influence, along with its opposition to any Asian alliance with the US, as seen for instance in Nehru’s criticism of the Manila Pact.

D. S. Senanayake’s insistence on defence and external affairs pacts with Britain in the run-up to the 1947 Constitution, even in the face of opposition from some of his colleagues, would have been fanned by perturbing declarations made by someone who happened to be the leader of the region’s biggest powerhouse. My argument, however, is that this couldn’t have been the only factor: the ideological orientation of the elite, in South Asia’s most dependent postcolonial plantation economy, would have played a role there too. After all the scope of foreign policy formulation by a head of state is as influenced by internal determinants, like a country’s political system, as it is by external determinants.

D. S. Senanayake’s insistence on defence and external affairs pacts with Britain in the run-up to the 1947 Constitution, even in the face of opposition from some of his colleagues, would have been fanned by perturbing declarations made by someone who happened to be the leader of the region’s biggest powerhouse. My argument, however, is that this couldn’t have been the only factor: the ideological orientation of the elite, in South Asia’s most dependent postcolonial plantation economy, would have played a role there too. After all the scope of foreign policy formulation by a head of state is as influenced by internal determinants, like a country’s political system, as it is by external determinants.

Fortunately, the so-called “Indo-Ceylon problem” as commentators referred to it then never spilt over to a conflict. But the differences between Indian and Sri Lankan political elites, especially on the issue of immigration, compelled the Sri Lankan government to take on the security of an extra-regional power which had much in common with the ruling elite against a regional superpower which did not. Here was realpolitik at an almost tribal level: an elite politico-economic ideology shaping the foreign relations of a nation.

In their choice of an extra-regional bargaining chip, that elite thus attempted to balance two competing interests – retaining India’s friendship while counterbalancing it – with another, party ideology. That is why the UNP under the two Senanayakes aligned with Britain, while John Kotelawala pivoted to the US in his friendship with John Forster Dulles and his anxiety to join SEATO; Sirimavo Bandaranaike’s later tilt to China has been described, by at least one scholar, as serving the same end from a leftwing vantage point.

India, however, was to remain the regional powerhouse. J. R. Jayewardene’s failed attempt to join ASEAN, coming in a quarter century after Kotelawala’s campaign to join SEATO irked Nehru, signalled that not even the pro-Western front could dampen the Indian factor. Both the political right and left recognised this; more so the latter, in fact, since Kotelawala and Jayewardene tried to sideline it to their peril, while neither S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike (who enjoyed a warmer rapport with Nehru than almost anyone in the UNP), nor his widow (who acted as mediator in the Sino-Indian War), did so. Therein lay the difference.

The writer can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

Sat Mag

October 13 at the Women’s T20 World Cup: Injury concerns for Australia ahead of blockbuster game vs India

Australia vs India

Sharjah, 6pm local time

Australia have major injury concerns heading into the crucial clash. Just four balls into the match against Pakistan, Tayla Vlaeminck was out with a right shoulder dislocation. To make things worse, captain Alyssa Healy suffered an acute right foot injury while batting on 37 as she hobbled off the field with Australia needing 14 runs to win. Both players went for scans on Saturday.

India captain Harmanpreet Kaur who had hurt her neck in the match against Pakistan, turned up with a pain-relief patch on the right side of her neck during the Sri Lanka match. She also didn’t take the field during the chase. Fast bowler Pooja Vastrakar bowled full-tilt before the Sri Lanka game but didn’t play.

India will want a big win against Australia. If they win by more than 61 runs, they will move ahead of Australia, thereby automatically qualifying for the semi-final. In a case where India win by fewer than 60 runs, they will hope New Zealand win by a very small margin against Pakistan on Monday. For instance, if India make 150 against Australia and win by exactly 10 runs, New Zealand need to beat Pakistan by 28 runs defending 150 to go ahead of India’s NRR. If India lose to Australia by more than 17 runs while chasing a target of 151, then New Zealand’s NRR will be ahead of India, even if Pakistan beat New Zealand by just 1 run while defending 150.

Overall, India have won just eight out of 34 T20Is they’ve played against Australia. Two of those wins came in the group-stage games of previous T20 World Cups, in 2018 and 2020.

Australia squad:

Alyssa Healy (capt & wk), Darcie Brown, Ashleigh Gardner, Kim Garth, Grace Harris, Alana King, Phoebe Litchfield, Tahlia McGrath, Sophie Molineux, Beth Mooney, Ellyse Perry, Megan Schutt, Annabel Sutherland, Tayla Vlaeminck, Georgia Wareham

India squad:

Harmanpreet Kaur (capt), Smriti Mandhana (vice-capt), Yastika Bhatia (wk), Shafali Verma, Deepti Sharma, Jemimah Rodrigues, Richa Ghosh (wk), Pooja Vastrakar, Arundhati Reddy, Renuka Singh, D Hemalatha, Asha Sobhana, Radha Yadav, Shreyanka Patil, S Sajana

Tournament form guide:

Australia have three wins in three matches and are coming into this contest having comprehensively beaten Pakistan. With that win, they also all but sealed a semi-final spot thanks to their net run rate of 2.786. India have two wins in three games. In their previous match, they posted the highest total of the tournament so far – 172 for 3 and in return bundled Sri Lanka out for 90 to post their biggest win by runs at the T20 World Cup.

Players to watch:

Two of their best batters finding their form bodes well for India heading into the big game. Harmanpreet and Mandhana’s collaborative effort against Pakistan boosted India’s NRR with the semi-final race heating up. Mandhana, after a cautious start to her innings, changed gears and took on Sri Lanka’s spinners to make 50 off 38 balls. Harmanpreet, continuing from where she’d left against Pakistan, played a classic, hitting eight fours and a six on her way to a 27-ball 52. It was just what India needed to reinvigorate their T20 World Cup campaign.

[Cricinfo]

Sat Mag

Living building challenge

By Eng. Thushara Dissanayake

The primitive man lived in caves to get shelter from the weather. With the progression of human civilization, people wanted more sophisticated buildings to fulfill many other needs and were able to accomplish them with the help of advanced technologies. Security, privacy, storage, and living with comfort are the common requirements people expect today from residential buildings. In addition, different types of buildings are designed and constructed as public, commercial, industrial, and even cultural or religious with many advanced features and facilities to suit different requirements.

We are facing many environmental challenges today. The most severe of those is global warming which results in many negative impacts, like floods, droughts, strong winds, heatwaves, and sea level rise due to the melting of glaciers. We are experiencing many of those in addition to some local issues like environmental pollution. According to estimates buildings account for nearly 40% of all greenhouse gas emissions. In light of these issues, we have two options; we change or wait till the change comes to us. Waiting till the change come to us means that we do not care about our environment and as a result we would have to face disastrous consequences. Then how can we change in terms of building construction?

Before the green concept and green building practices come into play majority of buildings in Sri Lanka were designed and constructed just focusing on their intended functional requirements. Hence, it was much likely that the whole process of design, construction, and operation could have gone against nature unless done following specific regulations that would minimize negative environmental effects.

We can no longer proceed with the way we design our buildings which consumes a huge amount of material and non-renewable energy. We are very concerned about the food we eat and the things we consume. But we are not worrying about what is a building made of. If buildings are to become a part of our environment we have to design, build and operate them based on the same principles that govern the natural world. Eventually, it is not about the existence of the buildings, it is about us. In other words, our buildings should be a part of our natural environment.

The living building challenge is a remarkable design philosophy developed by American architect Jason F. McLennan the founder of the International Living Future Institute (ILFI). The International Living Future Institute is an environmental NGO committed to catalyzing the transformation toward communities that are socially just, culturally rich, and ecologically restorative. Accordingly, a living building must meet seven strict requirements, rather certifications, which are called the seven “petals” of the living building. They are Place, Water, Energy, Equity, Materials, Beauty, and Health & Happiness. Presently there are about 390 projects around the world that are being implemented according to Living Building certification guidelines. Let us see what these seven petals are.

Place

This is mainly about using the location wisely. Ample space is allocated to grow food. The location is easily accessible for pedestrians and those who use bicycles. The building maintains a healthy relationship with nature. The objective is to move away from commercial developments to eco-friendly developments where people can interact with nature.

Water

It is recommended to use potable water wisely, and manage stormwater and drainage. Hence, all the water needs are captured from precipitation or within the same system, where grey and black waters are purified on-site and reused.

Energy

Living buildings are energy efficient and produce renewable energy. They operate in a pollution-free manner without carbon emissions. They rely only on solar energy or any other renewable energy and hence there will be no energy bills.

Equity

What if a building can adhere to social values like equity and inclusiveness benefiting a wider community? Yes indeed, living buildings serve that end as well. The property blocks neither fresh air nor sunlight to other adjacent properties. In addition, the building does not block any natural water path and emits nothing harmful to its neighbors. On the human scale, the equity petal recognizes that developments should foster an equitable community regardless of an individual’s background, age, class, race, gender, or sexual orientation.

Materials

Materials are used without harming their sustainability. They are non-toxic and waste is minimized during the construction process. The hazardous materials traditionally used in building components like asbestos, PVC, cadmium, lead, mercury, and many others are avoided. In general, the living buildings will not consist of materials that could negatively impact human or ecological health.

Beauty

Our physical environments are not that friendly to us and sometimes seem to be inhumane. In contrast, a living building is biophilic (inspired by nature) with aesthetical designs that beautify the surrounding neighborhood. The beauty of nature is used to motivate people to protect and care for our environment by connecting people and nature.

Health & Happiness

The building has a good indoor and outdoor connection. It promotes the occupants’ physical and psychological health while causing no harm to the health issues of its neighbors. It consists of inviting stairways and is equipped with operable windows that provide ample natural daylight and ventilation. Indoor air quality is maintained at a satisfactory level and kitchen, bathrooms, and janitorial areas are provided with exhaust systems. Further, mechanisms placed in entrances prevent any materials carried inside from shoes.

The Bullitt Center building

Bullitt Center located in the middle of Seattle in the USA, is renowned as the world’s greenest commercial building and the first office building to earn Living Building certification. It is a six-story building with an area of 50,000 square feet. The area existed as a forest before the city was built. Hence, the Bullitt Center building has been designed to mimic the functions of a forest.

The energy needs of the building are purely powered by the solar system on the rooftop. Even though Seattle is relatively a cloudy city the Bullitt Center has been able to produce more energy than it needed becoming one of the “net positive” solar energy buildings in the world. The important point is that if a building is energy efficient only the area of the roof is sufficient to generate solar power to meet its energy requirement.

It is equipped with an automated window system that is able to control the inside temperature according to external weather conditions. In addition, a geothermal heat exchange system is available as the source of heating and cooling for the building. Heat pumps convey heat stored in the ground to warm the building in the winter. Similarly, heat from the building is conveyed into the ground during the summer.

The potable water needs of the building are achieved by treating rainwater. The grey water produced from the building is treated and re-used to feed rooftop gardens on the third floor. The black water doesn’t need a sewer connection as it is treated to a desirable level and sent to a nearby wetland while human biosolid is diverted to a composting system. Further, nearly two third of the rainwater collected from the roof is fed into the groundwater and the process resembles the hydrologic function of a forest.

It is encouraging to see that most of our large-scale buildings are designed and constructed incorporating green building concepts, which are mainly based on environmental sustainability. The living building challenge can be considered an extension of the green building concept. Amanda Sturgeon, the former CEO of the ILFI, has this to say in this regard. “Before we start a project trying to cram in every sustainable solution, why not take a step outside and just ask the question; what would nature do”?

Sat Mag

Something of a revolution: The LSSP’s “Great Betrayal” in retrospect

By Uditha Devapriya

On June 7, 1964, the Central Committee of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party convened a special conference at which three resolutions were presented. The first, moved by N. M. Perera, called for a coalition with the SLFP, inclusive of any ministerial portfolios. The second, led by the likes of Colvin R. de Silva, Leslie Goonewardena, and Bernard Soysa, advocated a line of critical support for the SLFP, but without entering into a coalition. The third, supported by the likes of Edmund Samarakkody and Bala Tampoe, rejected any form of compromise with the SLFP and argued that the LSSP should remain an independent party.

The conference was held a year after three parties – the LSSP, the Communist Party, and Philip Gunawardena’s Mahajana Eksath Peramuna – had founded a United Left Front. The ULF’s formation came in the wake of a spate of strikes against the Sirimavo Bandaranaike government. The previous year, the Ceylon Transport Board had waged a 17-day strike, and the harbour unions a 60-day strike. In 1963 a group of working-class organisations, calling itself the Joint Committee of Trade Unions, began mobilising itself. It soon came up with a common programme, and presented a list of 21 radical demands.

In response to these demands, Bandaranaike eventually supported a coalition arrangement with the left. In this she was opposed, not merely by the right-wing of her party, led by C. P. de Silva, but also those in left parties opposed to such an agreement, including Bala Tampoe and Edmund Samarakkody. Until then these parties had never seen the SLFP as a force to reckon with: Leslie Goonewardena, for instance, had characterised it as “a Centre Party with a programme of moderate reforms”, while Colvin R. de Silva had described it as “capitalist”, no different to the UNP and by default as bourgeois as the latter.

The LSSP’s decision to partner with the government had a great deal to do with its changing opinions about the SLFP. This, in turn, was influenced by developments abroad. In 1944, the Fourth International, which the LSSP had affiliated itself with in 1940 following its split with the Stalinist faction, appointed Michel Pablo as its International Secretary. After the end of the war, Pablo oversaw a shift in the Fourth International’s attitude to the Soviet states in Eastern Europe. More controversially, he began advocating a strategy of cooperation with mass organisations, regardless of their working-class or radical credentials.

Pablo argued that from an objective perspective, tensions between the US and the Soviet Union would lead to a “global civil war”, in which the Soviet Union would serve as a midwife for world socialist revolution. In such a situation the Fourth International would have to take sides. Here he advocated a strategy of entryism vis-à-vis Stalinist parties: since the conflict was between Stalinist and capitalist regimes, he reasoned, it made sense to see the former as allies. Such a strategy would, in his opinion, lead to “integration” into a mass movement, enabling the latter to rise to the level of a revolutionary movement.

Though controversial, Pablo’s line is best seen in the context of his times. The resurgence of capitalism after the war, and the boom in commodity prices, had a profound impact on the course of socialist politics in the Third World. The stunted nature of the bourgeoisie in these societies had forced left parties to look for alternatives. For a while, Trotsky had been their guide: in colonial and semi-colonial societies, he had noted, only the working class could be expected to see through a revolution. This entailed the establishment of workers’ states, but only those arising from a proletarian revolution: a proposition which, logically, excluded any compromise with non-radical “alternatives” to the bourgeoisie.

To be sure, the Pabloites did not waver in their support for workers’ states. However, they questioned whether such states could arise only from a proletarian revolution. For obvious reasons, their reasoning had great relevance for Trotskyite parties in the Third World. The LSSP’s response to them showed this well: while rejecting any alliance with Stalinist parties, the LSSP sympathised with the Pabloites’ advocacy of entryism, which involved a strategic orientation towards “reformist politics.” For the world’s oldest Trotskyite party, then going through a series of convulsions, ruptures, and splits, the prospect of entering the reformist path without abandoning its radical roots proved to be welcoming.

Writing in the left-wing journal Community in 1962, Hector Abhayavardhana noted some of the key concerns that the party had tried to resolve upon its formation. Abhayavardhana traced the LSSP’s origins to three developments: international communism, the freedom struggle in India, and local imperatives. The latter had dictated the LSSP’s manifesto in 1936, which included such demands as free school books and the use of Sinhala and Tamil in the law courts. Abhayavardhana suggested, correctly, that once these imperatives changed, so would the party’s focus, though within a revolutionary framework. These changes would be contingent on two important factors: the establishment of universal franchise in 1931, and the transfer of power to the local bourgeoisie in 1948.

Paradoxical as it may seem, the LSSP had entered the arena of radical politics through the ballot box. While leading the struggle outside parliament, it waged a struggle inside it also. This dual strategy collapsed when the colonial government proscribed the party and the D. S. Senanayake government disenfranchised plantation Tamils. Suffering two defeats in a row, the LSSP was forced to think of alternatives. That meant rethinking categories such as class, and grounding them in the concrete realities of the country.

This was more or less informed by the irrelevance of classical and orthodox Marxian analysis to the situation in Sri Lanka, specifically to its rural society: with a “vast amorphous mass of village inhabitants”, Abhayavardhana observed, there was no real basis in the country for a struggle “between rich owners and the rural poor.” To complicate matters further, reforms like the franchise and free education, which had aimed at the emancipation of the poor, had in fact driven them away from “revolutionary inclinations.” The result was the flowering of a powerful rural middle-class, which the LSSP, to its discomfort, found it could not mobilise as much as it had the urban workers and plantation Tamils.

Where else could the left turn to? The obvious answer was the rural peasantry. But the rural peasantry was in itself incapable of revolution, as Hector Abhayavardhana has noted only too clearly. While opposing the UNP’s Westernised veneer, it did not necessarily oppose the UNP’s overtures to Sinhalese nationalism. As historians like K. M. de Silva have observed, the leaders of the UNP did not see their Westernised ethos as an impediment to obtaining support from the rural masses. That, in part at least, was what motivated the Senanayake government to deprive Indian estate workers of their most fundamental rights, despite the existence of pro-minority legal safeguards in the Soulbury Constitution.

To say this is not to overlook the unique character of the Sri Lankan rural peasantry and petty bourgeoisie. Orthodox Marxists, not unjustifiably, characterise the latter as socially and politically conservative, tilting more often than not to the right. In Sri Lanka, this has frequently been the case: they voted for the UNP in 1948 and 1952, and voted en masse against the SLFP in 1977. Yet during these years they also tilted to the left, if not the centre-left: it was the petty bourgeoisie, after all, which rallied around the SLFP, and supported its more important reforms, such as the nationalisation of transport services.

One must, of course, be wary of pasting the radical tag on these measures and the classes that ostensibly stood for them. But if the Trotskyite critique of the bourgeoisie – that they were incapable of reform, even less revolution – holds valid, which it does, then the left in the former colonies of the Third World had no alternative but to look elsewhere and to be, as Abhayavardhana noted, “practical men” with regard to electoral politics. The limits within which they had to work in Sri Lanka meant that, in the face of changing dynamics, especially among the country’s middle-classes, they had to change their tactics too.

Meanwhile, in 1953, the Trotskyite critique of Pabloism culminated with the publication of an Open Letter by James Cannon, of the US Socialist Workers’ Party. Cannon criticised the Pabloite line, arguing that it advocated a policy of “complete submission.” The publication of the letter led to the withdrawal of the International Committee of the Fourth International from the International Secretariat. The latter, led by Pablo, continued to influence socialist parties in the Third World, advocating temporary alliances with petty bourgeois and centrist formations in the guise of opposing capitalist governments.

For the LSSP, this was a much-needed opening. Even as late as 1954, three years after S. W. R. D. Bandaranaike formed the SLFP, the LSSP continued to characterise the latter as the alternative bourgeois party in Ceylon. Yet this did not deter it from striking up no contest pacts with Bandaranaike at the 1956 election, a strategy that went back to November 1951, when the party requested the SLFP to hold a discussion about the possibility of eliminating contests in the following year’s elections. Though it extended critical support to the MEP government in 1956, the LSSP opposed the latter once it enacted emergency measures in 1957, mobilising trade union action for a period of three years.

At the 1960 election the LSSP contested separately, with the slogan “N. M. for P.M.” Though Sinhala nationalism no longer held sway as it had in 1956, the LSSP found itself reduced to a paltry 10 seats. It was against this backdrop that it began rethinking its strategy vis-à-vis the ruling party. At the throne speech in April 1960, Perera openly declared that his party would not stabilise the SLFP. But a month later, in May, he called a special conference, where he moved a resolution for a coalition with the party. As T. Perera has noted in his biography of Edmund Samarakkody, the response to the resolution unearthed two tendencies within the oppositionist camp: the “hardliners” who opposed any compromise with the SLFP, including Samarakkody, and the “waverers”, including Leslie Goonewardena.

These tendencies expressed themselves more clearly at the 1964 conference. While the first resolution by Perera called for a complete coalition, inclusive of Ministries, and the second rejected a coalition while extending critical support, the third rejected both tactics. The outcome of the conference showed which way these tendencies had blown since they first manifested four years earlier: Perera’s resolution obtained more than 500 votes, the second 75 votes, the third 25. What the anti-coalitionists saw as the “Great Betrayal” of the LSSP began here: in a volte-face from its earlier position, the LSSP now held the SLFP as a party of a radical petty bourgeoisie, capable of reform.

History has not been kind to the LSSP’s decision. From 1970 to 1977, a period of less than a decade, these strategies enabled it, as well as the Communist Party, to obtain a number of Ministries, as partners of a petty bourgeois establishment. This arrangement collapsed the moment the SLFP turned to the right and expelled the left from its ranks in 1975, in a move which culminated with the SLFP’s own dissolution two years later.

As the likes of Samarakkody and Meryl Fernando have noted, the SLFP needed the LSSP and Communist Party, rather than the other way around. In the face of mass protests and strikes in 1962, the SLFP had been on the verge of complete collapse. The anti-coalitionists in the LSSP, having established themselves as the LSSP-R, contended later on that the LSSP could have made use of this opportunity to topple the government.

Whether or not the LSSP could have done this, one can’t really tell. However, regardless of what the LSSP chose to do, it must be pointed out that these decades saw the formation of several regimes in the Third World which posed as alternatives to Stalinism and capitalism. Moreover, the LSSP’s decision enabled it to see through certain important reforms. These included Workers’ Councils. Critics of these measures can point out, as they have, that they could have been implemented by any other regime. But they weren’t. And therein lies the rub: for all its failings, and for a brief period at least, the LSSP-CP-SLFP coalition which won elections in 1970 saw through something of a revolution in the country.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist based in Sri Lanka who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Opinion4 days ago

Opinion4 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Features4 days ago

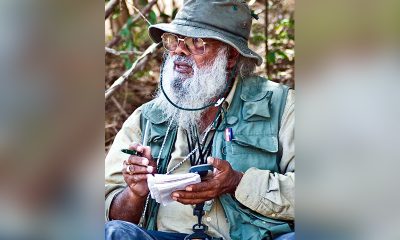

Features4 days agoA life in colour and song: Rajika Gamage’s new bird guide captures Sri Lanka’s avian soul

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCabinet nod for the removal of Cess tax imposed on imported good

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoSri Lanka to Host First-Ever World Congress on Snakes in Landmark Scientific Milestone

-

Latest News2 days ago

Latest News2 days agoAround 140 people missing after Iranian navy ship sinks off coast of Sri Lanka

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoLegal experts decry move to demolish STC dining hall