Features

Sri Lanka under British rule : Neither Gemeinschaft nor Gesellschaft

By Uditha Devapriya

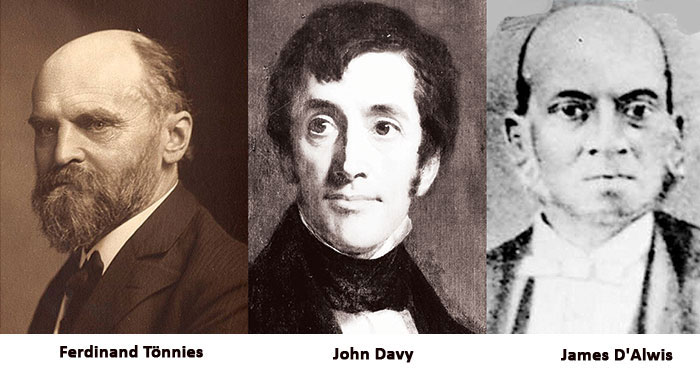

Since at least Marx and Malinowski, anthropologists have been fascinated by, and focused on, the links between “primitive-tribal” and “modern-secular” societies. I use these terms with a pinch of salt – hence the asterisks – for the simple reason that no society can be said to fit one case or the other. In its initial phase the social sciences did, admittedly, distinguish between the two, and took the teleological position that the one would lead to another: hence Ferdinand Tönnies’s idea of a progression from Gemeinschaft to Gesellschaft. Such progressions were depicted as long, eventual, but inevitable, and were accepted widely at a time when Europe, the harbinger of industrialisation and colonialism, had consolidated its position as the main, if not sole, locomotive of world history.

I have pointed out earlier, in this column, that Europe’s encounters with the non-West – Africa and Asia, basically – did not spur the kind of transition from tribalism to modernity which the most benighted missionary and colonial official had publicly advocated. This was no less true in India than it was in Sri Lanka. To give a simple and much used example, upon their annexation of Kandy, the colonial government did not do away with the caste-based duty system, and corvee labour, at once. Unlike scholars and romantics who envisioned a supposedly nobler role for the colonising West, the administrators and officials working on the ground saw the need to retain precapitalist, and thus primitive, social relations, in order to legitimise their rule over the newly acquired territories.

One discerns an intriguing, if fundamental, disconnect or contradiction here, between the supposed aims and the actual, lived experience of colonial rule. If the objective of colonial rule was indeed to transform the societies they had acquired by force and compulsion, then the relationship between the coloniser and colonised had to go beyond the position of mere dependence which colonised territories were subjected to. We know, however, that this was never the case. India, for instance, accounted for a quarter of the world’s industrial production, and British rule smothered its textile sector in the interests of ensuring a market for British textile exports. What this reveals is that, regardless of what scholars at the time may have believed, the West was primarily interested in sabotaging the national industries of the non-West, rather than in transforming their societies.

It was the destruction of these industries, as well as official patronage of precapitalist social relations, especially in regions like Kandy, that hindered the long progression from tribalism to modernity which the likes of Tönnies, Durkheim, and Henry Maine advocated. The latter were, strictly speaking, not propagandists or mouthpieces for colonialism: it would be wrong to consider them so on the basis of their Western and European background alone. But they were products of their time, and in their time the Western view of non-Western countries gradually being subsumed by colonialism and then developing into capitalist and modernist societies was more or less accepted. Even Marx, in his initial despatches on India, pondered whether British colonialism would beneficially impact that country’s historical and economic trajectory. Of course, Marx later changed his position, proving himself an exception.

In any case, these processes ran their course more discernibly, and thoroughly, in Sri Lanka than they did in India, where, perhaps because of its size or its plurality, colonial rule did not, and could not, destroy its industrial base or pre-empt the formation of an industrial (and somewhat anti-imperialist) bourgeoisie. In Sri Lanka, by contrast, British rule managed successfully to hinder the progression from feudalism to capitalism, thereby preventing it from achieving a transition from “tribalism” to “modernity.”

Since I have reflected on these concerns in my recent essay on Maduwanwela Dissawe and the temples of the South, I will limit my analysis here to another area where colonial rule had an undeniably distinct, and paradoxical, impact on local society.

Education had long been viewed, even by the Portuguese, and more prominently by the Dutch, as a useful instrument for the consolidation of colonial power. The Dutch, through their network of parish schools, were interested more in eradicating Portuguese power – with little to no effect, as the enduring popularity of Catholicism, even today, illustrates – than in educating local elites. The latter objective formed the cornerstone of British policy on education, particularly after the Colebrooke-Cameron reforms of 1833.

The British government was itself not in one mind over education, and it was hardly in agreement with missionary enclaves who were interested more in converting locals to their specific brand or denomination. But by and large, a sort of tacit understanding developed between the two that these schools would inculcate Western values, and educate a class of locals who could staff the civil administrative service.

The first British officials to set foot in Kandy – among them, John Davy – were demonstrably surprised at the state of education there. Products of elite public schools and universities themselves, they were astonished by how much of a widespread institution education had become in the highlands, administered by the pansalas and limited to the male population. In Britain at the time, education had become the preserve of the old aristocracy and an emerging bourgeoisie. It was this model, based fundamentally on filtration theory – or the entrenchment of a minority, to the exclusion of the masses – which British officials sought to enforce in the island. By contrast, missionary bodies were interested in taking their gospel as far as possible, even preaching it in the vernacular. Yet even though they were in conflict with the government’s more utilitarian approach to education, over the years they conformed to that approach while pursuing their own objectives.

For obvious and logical reasons, the institutions of a colonial society – the superstructure, to borrow Marxist terminology – acutely reflect, or appropriate, that society’s economic base. In Sri Lanka, colonialism had transformed if not transmogrified precapitalist social relations without fundamentally challenging them: hence the government’s decision to retain rather than overhaul caste and rajakariya, and hence its decision to co-opt rather than eradicate the Kandyan aristocracy. Within such a setup, a transition from tribalism to modernity was simply not possible, particularly after the grafting of a plantation economy which reduced the peasantry to a position of dependence while undercutting them through the import of cheap, indentured, and perpetually exploited labour from South India.

It goes without saying that this setup was well reflected in the schools and other educational institutions that the colonial State established in the mid-19th century. How so? First and foremost, these schools reaffirmed the colonial State’s advocacy, and enforcement, of elite filtration, or education for a minority as opposed to the masses. In areas like Kandy, the State did not interfere when missionary bodies set up schools, because it provided them with the opportunity to educate the children of native elites and European planters. The colonial State itself did not own the kind of “superior” schools that missionary bodies did: it had the Colombo Academy, but that was in Colombo. Elsewhere, as far as the aims of the State and missionary enclaves went, laissez-faire ruled the day. Individual governors may have held views that were antithetical to the aims of these enclaves, but again, such rifts were temporary, and were in any case resolved by succeeding governors.

Secondly, the curriculum of these schools was, in comparison to the needs of a society that had yet not industrialised, hardly modern or progressive. The students of these institutions not only learnt the literature, history, and culture of a society far removed from them, their very education distanced them from the society to which they had been born. This had the dual effect of distancing themselves from their roots while failing to root them in the society of the “mother country”, or the metropole. James d’Alwis’s memoirs, in which he recounts the pressure to conform and uproot himself that he experienced at the Colombo Academy, illustrate this dilemma well. Many years later, Ralph Pieris could recount his childhood at the Academy – by then renamed Royal College – in just about the same terms. I quote him in full, simply because it sheds light on what these schools stood for.

“The Ceylon schools supported an authoritarian regime in the classroom where the rod was not spared, idealised ‘manly’ sports such as boxing and rugger, while a disciplined military apprenticeship was provided by the cadet battalion. Many adults have hankering fixation on school life, the joys of cricket; and masochistic adoration or the father-figures of teachers. even if they were responsible for sadistic and humiliating physical chastisement… All too frequently I have witnessed the tragicomic spectacle of elderly men leading a hollow existence, pitiful spectators of sports they can no longer actively participate in, who have rejoiced only in the transient marvel of their physical strength, [to] discover in later life that their range has become restricted and their interests few.”

Ralph Pieris, Sociology as a Calling: A Desultory Memoir

Modern Sri Lanka Studies, Vol. 3, No. 2, 1988, pp 1-33

Pieris’s observation leads me to my third point, which is that the elitism engendered and perpetuated by these institutions continued long after colonial rule, and in fact continues today. There are, of course, important differences between colonial and post-colonial society. The right to vote, and free education, emancipated the masses from the fields or “avocations” to which the colonial State had restricted them. These developments were not wholeheartedly accepted by the elite of the day: in criticising the Central School System, for instance, a member of the Colombo upper class remarked that the new schools would never be as good as the elite ones. Yet such reforms had in themselves been necessitated by the right to vote, and could not be prevented or pre-empted. Despite the machinations of the English-speaking bourgeoisie – which either accepted these reforms or chose to migrate from the country – free education became well established, even in the schools which they had attended, and to which many of them continued sending their sons.

In my essay on the Royal College Hostel, published last August, I noted that independence brought about a transfer of power from the legatees of British power to an indigenous class. In elite schools, I added, this transfer was not so much from the upper echelons to the lower classes as it was from an elite to an upward aspiring petty bourgeoisie, or intermediate elite. Such transformations did not fundamentally put to question, much less challenge, the elitist structures that had been implanted in these establishments by the British government. This is why Pieris’s memoirs paint an accurate picture of these institutions, not just from his time but also from ours: Pieris’s description of past pupils’ “hankering fixation on school life, the joys of cricket” and of “elderly men leading a hollow existence, pitiful spectators or sports they can no longer actively participate in”, to give one example, is amply visible at the many matches, parades, and functions organised by these schools today.

All this goes back to my original point, that British rule did not liberate colonial societies, like ours, from our tribalist past. A careful examination of the institutions which were set up by colonial officials here, during that period, should make that much clear. The transition from colonial to post-colonial society has not really challenged the status quo. If at all, it has only substituted the domination of one social class for that of another: the petty bourgeoisie, for the Anglicised colonial elite. Against such a backdrop, it behoves us to ask what exactly must be done to ensure, not merely the eradication of colonial-precapitalist remnants in these institutions, but the eventual progression, in our country, from the colonial-tribalist setup to which it continues to be tethered, 75 years after independence, to a truly modern, secular, and progressive society. Such a transformation requires a radical shift in our perceptions of education, governance, and political reform. Yet it is needed, especially at a time when mass anger against the elite class has reached fever pitch.

The writer is an international relations analyst, researcher, and columnist who can be reached at udakdev1@gmail.com.

Features

Misinterpreting President Dissanayake on National Reconciliation

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has been investing his political capital in going to the public to explain some of the most politically sensitive and controversial issues. At a time when easier political choices are available, the president is choosing the harder path of confronting ethnic suspicion and communal fears. There are three issues in particular on which the president’s words have generated strong reactions. These are first with regard to Buddhist pilgrims going to the north of the country with nationalist motivations. Second is the controversy relating to the expansion of the Tissa Raja Maha Viharaya, a recently constructed Buddhist temple in Kankesanturai which has become a flashpoint between local Tamil residents and Sinhala nationalist groups. Third is the decision not to give the war victory a central place in the Independence Day celebrations.

Even in the opposition, when his party held only three seats in parliament, Anura Kumara Dissanayake took his role as a public educator seriously. He used to deliver lengthy, well researched and easily digestible speeches in parliament. He continues this practice as president. It can be seen that his statements are primarily meant to elevate the thinking of the people and not to win votes the easy way. The easy way to win votes whether in Sri Lanka or elsewhere in the world is to rouse nationalist and racist sentiments and ride that wave. Sri Lanka’s post independence political history shows that narrow ethnic mobilisation has often produced short term electoral gains but long term national damage.

Sections of the opposition and segments of the general public have been critical of the president for taking these positions. They have claimed that the president is taking these positions in order to obtain more Tamil votes or to appease minority communities. The same may be said in reverse of those others who take contrary positions that they seek the Sinhala votes. These political actors who thrive on nationalist mobilisation have attempted to portray the president’s statements as an abandonment of the majority community. The president’s actions need to be understood within the larger framework of national reconciliation and long term national stability.

Reconciler’s Duty

When the president referred to Buddhist pilgrims from the south going to the north, he was not speaking about pilgrims visiting long established Buddhist heritage sites such as Nagadeepa or Kandarodai. His remarks were directed at a specific and highly contentious development, the recently built Buddhist temple in Kankesanturai and those built elsewhere in the recent past in the north and east. The temple in Kankesanturai did not emerge from the religious needs of a local Buddhist community as there is none in that area. It has been constructed on land that was formerly owned and used by Tamil civilians and which came under military occupation as a high security zone. What has made the issue of the temple particularly controversial is that it was established with the support of the security forces.

The controversy has deepened because the temple authorities have sought to expand the site from approximately one acre to nearly fourteen acres on the basis that there was a historic Buddhist temple in that area up to the colonial period. However, the Tamil residents of the area fear that expansion would further displace surrounding residents and consolidate a permanent Buddhist religious presence in the present period in an area where the local population is overwhelmingly Hindu. For many Tamils in Kankesanturai, the issue is not Buddhism as a religion but the use of religion as a vehicle for territorial assertion and demographic changes in a region that bore the brunt of the war. Likewise, there are other parts of the north and east where other temples or places of worship have been established by the military personnel in their camps during their war-time occupation and questions arise regarding the future when these camps are finally closed.

There are those who have actively organised large scale pilgrimages from the south to make the Tissa temple another important religious site. These pilgrimages are framed publicly as acts of devotion but are widely perceived locally as demonstrations of dominance. Each such visit heightens tension, provokes protest by Tamil residents, and risks confrontation. For communities that experienced mass displacement, military occupation and land loss, the symbolism of a state backed religious structure on contested land with the backing of the security forces is impossible to separate from memories of war and destruction. A president committed to reconciliation cannot remain silent in the face of such provocations, however uncomfortable it may be to challenge sections of the majority community.

High-minded leadership

The controversy regarding the president’s Independence Day speech has also generated strong debate. In that speech the president did not refer to the military victory over the LTTE and also did not use the term “war heroes” to describe soldiers. For many Sinhala nationalist groups, the absence of these references was seen as an attempt to diminish the sacrifices of the armed forces. The reality is that Independence Day means very different things to different communities. In the north and east the same day is marked by protest events and mourning and as a “Black Day”, symbolising the consolidation of a state they continue to experience as excluding them and not empathizing with the full extent of their losses.

By way of contrast, the president’s objective was to ensure that Independence Day could be observed as a day that belonged to all communities in the country. It is not correct to assume that the president takes these positions in order to appease minorities or secure electoral advantage. The president is only one year into his term and does not need to take politically risky positions for short term electoral gains. Indeed, the positions he has taken involve confronting powerful nationalist political forces that can mobilise significant opposition. He risks losing majority support for his statements. This itself indicates that the motivation is not electoral calculation.

President Dissanayake has recognized that Sri Lanka’s long term political stability and economic recovery depend on building trust among communities that once peacefully coexisted and then lived through decades of war. Political leadership is ultimately tested by the willingness to say what is necessary rather than what is politically expedient. The president’s recent interventions demonstrate rare national leadership and constitute an attempt to shift public discourse away from ethnic triumphalism and toward a more inclusive conception of nationhood. Reconciliation cannot take root if national ceremonies reinforce the perception of victory for one community and defeat for another especially in an internal conflict.

BY Jehan Perera

Features

Recovery of LTTE weapons

I have read a newspaper report that the Special Task Force of Sri Lanka Police, with help of Military Intelligence, recovered three buried yet well-preserved 84mm Carl Gustaf recoilless rocket launchers used by the LTTE, in the Kudumbimalai area, Batticaloa.

These deadly weapons were used by the LTTE SEA TIGER WING to attack the Sri Lanka Navy ships and craft in 1990s. The first incident was in February 1997, off Iranativu island, in the Gulf of Mannar.

Admiral Cecil Tissera took over as Commander of the Navy on 27 January, 1997, from Admiral Mohan Samarasekara.

The fight against the LTTE was intensified from 1996 and the SLN was using her Vanguard of the Navy, Fast Attack Craft Squadron, to destroy the LTTE’s littoral fighting capabilities. Frequent confrontations against the LTTE Sea Tiger boats were reported off Mullaitivu, Point Pedro and Velvetiturai areas, where SLN units became victorious in most of these sea battles, except in a few incidents where the SLN lost Fast Attack Craft.

Carl Gustaf recoilless rocket launchers

The intelligence reports confirmed that the LTTE Sea Tigers was using new recoilless rocket launchers against aluminium-hull FACs, and they were deadly at close quarter sea battles, but the exact type of this weapon was not disclosed.

The following incident, which occurred in February 1997, helped confirm the weapon was Carl Gustaf 84 mm Recoilless gun!

DATE: 09TH FEBRUARY, 1997, morning 0600 hrs.

LOCATION: OFF IRANATHIVE.

FACs: P 460 ISRAEL BUILT, COMMANDED BY CDR MANOJ JAYESOORIYA

P 452 CDL BUILT, COMMANDED BY LCDR PM WICKRAMASINGHE (ON TEMPORARY COMMAND. PROPER OIC LCDR N HEENATIGALA)

OPERATED FROM KKS.

CONFRONTED WITH LTTE ATTACK CRAFT POWERED WITH FOUR 250 HP OUT BOARD MOTORS.

TARGET WAS DESTROYED AND ONE LTTE MEMBER WAS CAPTURED.

LEADING MARINE ENGINEERING MECHANIC OF THE FAC CAME UP TO THE BRIDGE CARRYING A PROJECTILE WHICH WAS FIRED BY THE LTTE BOAT, DURING CONFRONTATION, WHICH PENETRATED THROUGH THE FAC’s HULL, AND ENTERED THE OICs CABIN (BETWEEN THE TWO BUNKS) AND HIT THE AUXILIARY ENGINE ROOM DOOR AND HAD FALLEN DOWN WITHOUT EXPLODING. THE ENGINE ROOM DOOR WAS HEAVILY DAMAGED LOOSING THE WATER TIGHT INTEGRITY OF THE FAC.

THE PROJECTILE WAS LATER HANDED OVER TO THE NAVAL WEAPONS EXPERTS WHEN THE FACs RETURNED TO KKS. INVESTIGATIONS REVEALED THE WEAPON USED BY THE ENEMY WAS 84 mm CARL GUSTAF SHOULDER-FIRED RECOILLESS GUN AND THIS PROJECTILE WAS AN ILLUMINATER BOMB OF ONE MILLION CANDLE POWER. BUT THE ATTACKERS HAS FAILED TO REMOVE THE SAFETY PIN, THEREFORE THE BOMB WAS NOT ACTIVATED.

Sea Tigers

Carl Gustaf 84 mm recoilless gun was named after Carl Gustaf Stads Gevärsfaktori, which, initially, produced it. Sweden later developed the 84mm shoulder-fired recoilless gun by the Royal Swedish Army Materiel Administration during the second half of 1940s as a crew served man- portable infantry support gun for close range multi-role anti-armour, anti-personnel, battle field illumination, smoke screening and marking fire.

It is confirmed in Wikipedia that Carl Gustaf Recoilless shoulder-fired guns were used by the only non-state actor in the world – the LTTE – during the final Eelam War.

It is extremely important to check the batch numbers of the recently recovered three launchers to find out where they were produced and other details like how they ended up in Batticaloa, Sri Lanka?

By Admiral Ravindra C. Wijegunaratne

By Admiral Ravindra C. Wijegunaratne

WV, RWP and Bar, RSP, VSV, USP, NI (M) (Pakistan), ndc, psn, Bsc (Hons) (War Studies) (Karachi) MPhil (Madras)

Former Navy Commander and Former Chief of Defence Staff

Former Chairman, Trincomalee Petroleum Terminals Ltd

Former Managing Director Ceylon Petroleum Corporation

Former High Commissioner to Pakistan

Features

Yellow Beatz … a style similar to K-pop!

Yes, get ready to vibe with Yellow Beatz, Sri Lanka’s awesome girl group, keen to take Sri Lankan music to the world with a style similar to K-pop!

Yes, get ready to vibe with Yellow Beatz, Sri Lanka’s awesome girl group, keen to take Sri Lankan music to the world with a style similar to K-pop!

With high-energy beats and infectious hooks, these talented ladies are here to shake up the music scene.

Think bold moves, catchy hooks, and, of course, spicy versions of old Sinhala hits, and Yellow Beatz is the package you won’t want to miss!

According to a spokesman for the group, Yellow Beatz became a reality during the Covid period … when everyone was stuck at home, in lockdown.

“First we interviewed girls, online, and selected a team that blended well, as four voices, and then started rehearsals. One of the cover songs we recorded, during those early rehearsals, unexpectedly went viral on Facebook. From that moment onward, we continued doing cover songs, and we received a huge response. Through that, we were able to bring back some beautiful Sri Lankan musical creations that were being forgotten, and introduce them to the new generation.”

The team members, I am told, have strong musical skills and with proper training their goal is to become a vocal group recognised around the world.

Believe me, their goal, they say, is not only to take Sri Lanka’s name forward, in the music scene, but to bring home a Grammy Award, as well.

“We truly believe we can achieve this with the love and support of everyone in Sri Lanka.”

The year 2026 is very special for Yellow Beatz as they have received an exceptional opportunity to represent Sri Lanka at the World Championships of Performing Arts in the USA.

Under the guidance of Chris Raththara, the Director for Sri Lanka, and with the blessings of all Sri Lankans, the girls have a great hope that they can win this milestone.

“We believe this will be a moment of great value for us as Yellow Beatz, and also for all Sri Lankans, and it will be an important inspiration for the future of our country.”

Along with all the preparation for the event in the USA, they went on to say they also need to manage their performances, original song recordings, and everything related.

The year 2026 is very special for Yellow Beatz

“We have strong confidence in ourselves and in our sincere intentions, because we are a team that studies music deeply, researches within the field, and works to take the uniqueness of Sri Lankan identity to the world.”

At present, they gather at the Voices Lab Academy, twice a week, for new creations and concert rehearsals.

This project was created by Buddhika Dayarathne who is currently working as a Pop Vocal lecturer at SLTC Campus. Voice Lab Academy is also his own private music academy and Yellow Beatz was formed through that platform.

Buddhika is keen to take Sri Lankan music to the world with a style similar to K-Pop and Yellow Beatz began as a result of that vision. With that same aim, we all work together as one team.

“Although it was a little challenging for the four of us girls to work together at first, we have united for our goal and continue to work very flexibly and with dedication. Our parents and families also give their continuous blessings and support for this project,” Rameesha, Dinushi, Newansa and Risuri said.

Last year, Yellow Beatz released their first original song, ‘Ihirila’ , and with everything happening this year, they are also preparing for their first album.

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoGREAT 2025–2030: Sri Lanka’s Green ambition meets a grid reality check

-

Editorial5 days ago

Editorial5 days agoAll’s not well that ends well?