Features

Scientists predict changes in snakebite risks in Sri Lanka by 2050

By Ifham Nizam

A team of international scientists has conducted a groundbreaking study predicting significant changes in snakebite risks across Sri Lanka by the year 2050.

The research, led by Gerardo Martín, with contributions from Joseph James Erinjery, Dileepa Ediriweera, Eyal Goldstein, Ruchira Somaweera, H Janaka de Silva, David G Lalloo, Takuya Iwamura, and Kris A Murray, focuses on how climate change, land use, and population growth may impact snakebite incidents in the country.

Sri Lanka, known as a global hotspot for snakebites, faces the unique challenge of balancing human development with the preservation of its rich biodiversity. The study used advanced models to explore different future scenarios and to understand how these global changes might alter the landscape of snakebite risks.

According to the findings, while the overall incidence of snakebite envenoming could drop by up to 23% from 2010 to 2050, the reality is more complex.

The researchers identified that snakebite risks could decrease in the tropical lowlands but may increase in the highlands due to shifts in snake populations and habitats. This key finding reveals how environmental and social changes might alter human-snake interactions in various parts of the country, creating a diverse and uneven risk landscape. The study suggests that these changes could be driven by factors such as climate warming, deforestation, urbanisation, and agricultural expansion, which together affect both snake behavior and human exposure to snakes.

According to Renowned herpetologist Dr. Somaweera, their study dives into how global changes are shaping up snakebite risks in Sri Lanka, a global snakebite hotspot. “Using advanced models, we projected that from 2010 to 2050, the overall incidence of snakebite envenoming might drop by up to 23%—but it’s not all good news,” he said adding: “The effects vary widely depending on where you are in the country and which global change scenario plays out. For some areas, especially with higher population growth and land cover shifts, we’re seeing more complexity and even some potential increases in snakebite risk.”

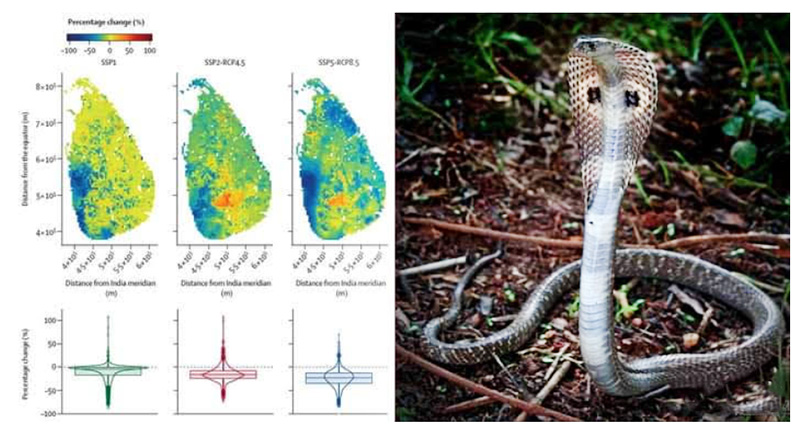

The research team explored three contrasting development scenarios: one where the world follows a sustainability pathway with no further greenhouse gas emissions (SSP1), a middle-of-the-road pathway with moderate emissions reductions (SSP2), and a fossil-fuel-driven pathway with limited emissions reductions (SSP5). Interestingly, the study also suggests that in the least sustainable scenarios—where environmental protections are weakest—overall snakebite risks might decrease.

The team stressed that this comes with a cost: a potential decline in biodiversity, which could harm the environment in the long run. This scenario suggests that the impact of human activities could be so severe that even the snakes, which thrive in various environments, might struggle to survive, leading to a reduction in snakebite incidents.

The implications of these findings are significant. The study underscores the need for joint efforts between public health and conservation agencies to develop integrated strategies that balance human health with environmental and climate considerations.

The researchers recommend increasing epidemiological surveillance, enhancing prevention through educational campaigns tailored to specific socio-ecological contexts, and improving access to protective equipment and effective treatments. These strategies, they argue, are essential to mitigating the potential rise in snakebite incidents in certain areas while safeguarding both human populations and the natural environment.

Sri Lanka’s well-established data on venomous snake populations and snakebite envenoming incidence provided a solid foundation for this study. The research builds on this knowledge by incorporating three critical components of global change—climate, land use change, and population growth—into a single predictive framework. This approach not only adds a new layer of understanding to the dynamics of snakebite risk but also highlights the importance of preparing for the future by considering the complex interactions between these factors.

As the world continues to grapple with the effects of global change, the findings of this study serve as a reminder of the interconnectedness of human health and environmental sustainability.

The scientists hope that their work will inform future policies and actions in Sri Lanka and other snakebite-prone regions, helping to protect both people and nature in the face of an uncertain future.