Features

Rights of Nature vis-à-vis Human Rights to Nature:

Earth Jurisprudence and Eco-centric Property Law – II

by Professor Emeritus Nimal Gunatilleke

University of Peradeniya

savnim@gmail.com)

(Continued from yesterday)

Rights of Nature Legalised

Since the early twenty-first century, governments and courts around the world have adopted a rapidly growing number of laws declaring that nature has rights. These laws take many forms, from local government bylaws to court decisions to national constitutions. They vary greatly in form, content, and legal effect.

Rights of Nature campaigns for aligning legal standards and principles with planetary boundaries and the law of Nature. Those campaigns include, among others, the Universal Declaration for the Rights of Mother Earth (2010), the Universal Declaration of Rights of Rivers, the Universal Declaration of Ocean Rights (UDOR), and the World Charter for Nature.

Several countries have recognised the Rights of Nature by establishing several constitutional, legislative, and judicial enactments that aim to provide legal protection for non-human entities and natural systems. By the end of March 2023, the Eco Jurisprudence Monitor documented 468 Rights of Nature (RoN) initiatives—which are efforts to adopt a RoN legal provision—across 29 countries, being more expressive in North America and Latin America, and less in Europe, Asia and Africa.

The first laws establishing legal structures that recognised the Rights of Nature were adopted by local municipalities in the United States in 2006. Tamaqua Borough, Schuylkill County, Pennsylvania, was the first community to enact the Rights of Nature. Since then, more than three dozen communities in the US have adopted such laws. In November 2010, the City of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, became the first major municipality in the United States to recognize the Rights of Nature.

In September 2008, Ecuador became the first country in the world to recognise the Rights of Nature in its constitution. Ecuadorian constitutional provisions promulgated in 2008, recognise the right of nature to exist, persist, evolve, and regenerate. Bolivia has also established the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth in 2010.

It needs to be emphasised here that although people have been talking about “sustainable development” for decades, very little has been done to change the structure of the law to actually achieve that goal. Laws recognizing the Rights of Nature finally will codify the concept of sustainable development. They disallow activities that would interfere with the functioning of natural systems that support human and natural life.

It has become increasingly clear that fulfilling the human right to a healthy environment is unachievable without a fundamental change in the relationship between humankind and nature. Thus, implementing and fulfilling a true human right to a healthy environment is dependent on the health of the natural environment itself. The human right to a healthy environment can only be achieved by securing the highest protections for the natural environment – by recognising in law the right of the environment itself to be healthy and thrive. These are the ways to promote a holistic approach to sustainable development in harmony with nature.

The Rights of Nature should have their foundation in environmental laws, which are based on the idea that the natural world has inherent value and rights that should be recognised and protected. However, at present, their elements have no standing, and environmental laws are fragile in the context of dominant systems insofar as they somehow continue to carry the burden of neo-colonial practices and Western property relations.

While science in the late twentieth century shifted to a systems-based perspective, describing natural systems and human populations as fundamentally interconnected on a shared planet, environmental laws generally had not evolved with this shift with a similar momentum.

Emerging Global Trends

Many jurisdictions worldwide are now increasingly recognising and integrating the principles of earth jurisprudence into their domestic legal frameworks either through the changes in their respective constitutions, legislation, or judicial activism. The Rights of Nature are legally protected in Bolivia, New Zealand, Ecuador, India, and several American communities, ranging from Santa Monica to Pittsburgh. These new laws regarding the Rights of Nature are branching out to protect endangered species and animals. Many countries around the world, including Switzerland, Portugal, France, Columbia, and Brazil, have specified a set of obligations to the government regarding nature and its protection.

Courts in the United States, Costa Rica, and India have ruled on cases about endangered species, stopped activities that harm them, and ruled to save these populations, including the snail darter, papilla, northern spotted owl, Asian lion, and Asiatic buffalo. These judicial decisions all have the same goal— enforcing the idea that all of life has value, and should not be used as human property; humans as well as the state have a responsibility to avoid causing harm to these species.

There are several examples of landscapes that are being governed or have been protected through legal models based on the Rights of Nature, e.g. Galapagos Marine Reserve (Ecuador), Manglares Cayapas Mataje Ecological Reserve (Ecuador), Whanganui River (New Zealand), Atrato River (Colombia), Magpie River (Canada), Mar Menor ( Spain), among others. There is an increasing trend to scale up this impact globally and achieve its effective implementation, to reach a permanent transformation in our ecosystem and landscape governance for the benefit of Nature and communities.

New Zealand was one of the first countries in the world to create and pass laws acknowledging that nature is no longer subject to human ownership. The new ideology in New Zealand acknowledges the fact that people are part of nature; they are not separate from it or dominant over it. These laws emphasise nature as a rights holder, as well as the importance of human responsibilities to uphold these rights. Two pieces of legislation – The Urewera Act of 2014 and Te Awa Tupua (Whanganui River Claims Settlements) Act of 2017 have granted legal personhood rights of Te Urewera National Park and the Whanganui River.

The Whanganui River will have its own legal identity with all the rights, duties, and liabilities of a legal person. The local Māori tribe wanted to treat the river as a living entity instead of treating it as property with others having ownership over it. Since the river has been granted legal recognition, if someone wants to harm the river, this would be the same as harming the particular local tribe.

Likewise, Te Urewera National Park owns itself and has legal standing, similar to the Whanganui River. Te Urewera is governed by a board of trustees whose mandate is to act on behalf of the National Park.

This was followed by court recognition of legal personhood for the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers in northern India. Rights of Nature legal provisions also now exist in Colombia, Mexico, and dozens of municipalities in the United States, and are being debated in a number of other nations.

In April 2018, the Colombian Supreme Court ruled that stronger efforts must be made against deforestation in the Amazon, and the country as a whole must be protected from the effects of climate change. In this ruling, the Colombian Amazon is granted personhood and thus is regarded as an entity with rights. This is the first such ruling in Latin America.

Sri Lankan Context:

- Map 1: Sri Lanka’S Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (Source: Maritime Boundaries Geodatabase, Flanders Marine Institute).

- Map 2: Cobalt-rich Afanasy Nikitin Seamount, which is in the central Indian Ocean, east of the Maldives and about 1,350 km (850 miles) from the Indian coast.)

Sri Lanka is a biodiversity-rich country like New Zealand, Ecuador, Colombia, India, etc. and is caught between the devil and the deep blue sea for being located in a geostrategic position abundantly endowed with strategically important natural resources. While being at the center of the Indian Ocean Sea Lanes of Communication (SLOC) with extensive ocean and land-based mineral resources including premium grade graphite and rare earth elements, some political analysts are of the view that Sri Lanka suffers from a ‘Paradox of Plenty’ or perhaps, a geostrategic ‘Resource Curse’. This phenomenon often afflicts countries blessed with abundant natural resources, like Sri Lanka.

An imminent threat to our unique biodiversity is upon us, once more, especially during this critical period of desperate struggle to emerge from the unprecedented economic crisis, the country has undergone in recent times. Some political analysts argue that the ‘staged default’ in 2022 would enable the IMF to effectively take control of strategic geopolitical positioning by influencing Sri Lanka’s economic policy initiatives compromising its sovereignty. We will be seeing the outcome of this hard bargaining in the near future.

Sri Lanka seems to be under severe pressure to part with some of its greatest natural treasures both on land and in the sea around us under the plans being hatched during the painful process of ‘debt restructuring’ for moving towards ‘debt sustainability’. Under the prevailing law, these priceless landscapes and seascapes are perceived from a human perspective as an object of law – a natural resource or property having a commodifiable, and disposable value meant to benefit human beings.

In addition to the terrestrial landmass, the virtually unexplored and untapped Sri Lanka’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) spans around 519,000 sq. km. and is almost eight times larger than the country’s landmass. Furthermore, Sri Lanka has submitted a claim for an extended area of seabed amounting to 23 times its land mass (1.4 million sq. km.) with exclusive rights to water resources, biological wealth, and the sea bed with rich mineral resources, oil, gas, and fisheries.

It has been proposed to develop a Blue Economic strategy in existing sectors, including oil, gas wind, solar, and geothermal exploration, and in emerging sectors like deep seabed mining for minerals. The race for minerals on the seafloor, seen as the next frontier of exploration has already begun and been likened to a new ‘gold rush’. Countries like China, Russia, and India are looking to extract a range of minerals like zinc, cobalt, and copper available on the seabed in the Indo-Pacific Oceanic region. These minerals are needed for modern hi-tech industries like electronics, automobiles, and clean energy. However, seabed mining, on the other hand, can result in irreversible harm to marine ecosystems, disrupting fragile habitats and jeopardising marine biodiversity. (See map 1: Map of the Sri Lankan Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (Source: Maritime Boundaries Geodatabase, Flanders Marine Institute).

Map of the Sri Lankan Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) (Source: Maritime Boundaries Geodatabase, Flanders Marine Institute). (See map 2: Cobalt-rich Afanasy Nikitin Seamount, which is in the central Indian Ocean, east of the Maldives and about 1,350 km (850 miles) from the Indian coast.)

In order to ensure that oceans will not be ravaged for human benefit, Sri Lanka must think beyond an anthropocentric legal framework and uphold the essence of Earth jurisprudence at the earliest available opportunity to avoid any protracted legal imbroglios in the future. In the light of these looming threats to the remaining ‘natural resources’ in the Sri Lankan landscape and ocean-scape under the present property law, it is high time that we too transform from an anthropocentric to eco-centric jurisprudence as being done in other biodiverse countries.

So far, very little has been done to change the structure of law to actually achieve an eco-centric sustainable development, judging from the outcomes of Environmental Impact Assessments and subsequent legal proceedings on the sustainable use of our natural resources. Laws recognizing the Rights of Nature need to be brought in to codify the concept of sustainable development. The human right to a healthy environment can only be achieved by securing the highest protections for the natural environment – by recognizing in the law the right of the environment itself to be healthy and thrive sustainably i.e. an ecocentric paradigm shift in our legal system.

Given the considerable commercial value attached to these virtually uncharted marine natural resources, they would have been, in all probability, a vital element in the ongoing debt restructuring negotiations with diverse stakeholders as Sri Lanka stands to benefit significantly from an emerging blue economic strategy. Blue economy is defined as the sustainable use of ocean resources for economic growth, jobs, and social and financial inclusion, with a focus on the preservation and restoration of ocean ecosystems and the services they provide according to the existing international and national jurisdictions.

Marine Pollution and Earth Jurisprudence

Maritime Sea Lanes of Communication in the Indian Ocean (Source : https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents/50184/50184-001-tacr-en.pdf)

The MV X-Press Pearl disaster which caused unprecedented damage to the Sri Lankan oceans and all those who form a part of these oceans will adversely affect the ocean and marine lives for many years to come. It has been repeatedly emphasized that environmental disasters affect not only human beings but all other living and nonliving species who share the planet with them. Therefore, it is unequivocal that these nonhuman beings shall be empowered to protect themselves against anthropogenic environmental disasters.

An excellent discourse on how Earth Jurisprudence could be integrated into the contemporary legal framework in Sri Lanka to protect its oceans and ocean species has been published by Dr. Asanka Edirisinghe of General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University (https://celp.cmb.ac.lk/team/mrs-asanka-edirisinghe/). She strongly underscores that the best method to empower oceans to fight against this level of pollution is the express recognition of Earth jurisprudence in the domestic legal framework. It respects oceans and ocean species as a salient and integral part of the wider Earth community, just like the man himself. Unfortunately, Earth jurisprudential principles are not comprehensively reflected in the contemporary legal framework aimed at the protection of oceans in Sri Lanka.

The environmental community should rally round Dr. Edirisinghe’s clarion call that the time has come when these crucial principles on Earth Jurisprudence must be integrated into the corpus of the contemporary law in Sri Lanka, following the examples set by the international community, to preserve oceans and all its members-the next frontier of exploitation – for the sake of all of the Earth community.

Features

Wishes, Resolutions and Climate Change

Exchanging greetings and resolving to do something positive in the coming year certainly create an uplifting atmosphere. Unfortunately, their effects wear off within the first couple of weeks, and most of the resolutions are forgotten for good. However, this time around, we must be different, because the nation is coming out of the most devastating natural disaster ever faced, the results of which will impact everyone for many years to come. Let us wish that we as a nation will have the courage and wisdom to resolve to do the right things that will make a difference in our lives now and prepare for the future. The truth is that future is going to be challenging for tropical islands like ours.

We must not have any doubts about global warming phenomenon and its impact on local weather patterns. Over its 4.5-billion-year history, the earth has experienced drastic climate changes, but it has settled into a somewhat moderate condition characterised by periods of glaciation and retreat over the last million years. Note that anatomically modern Homo sapiens have been around only for two to three hundred thousand years, and it is reasoned that this stable climate may have helped their civilisation. There have been five glaciation periods over the last five hundred thousand years, and these roughly hundred-thousand-year cycles are explained by the astronomical phenomenon known as the Milankovitch Cycle (the lows marked with stars in Figure 1). At present, the earth is in an inter glacial period and the next glaciation period will be in about eighty thousand years.

(See Figure 1. Glaciation Cycles)

(See Figure 1. Glaciation Cycles)

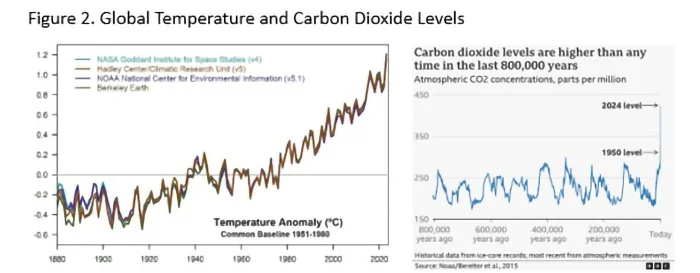

During these cycles, the global mean temperature has changed by about 7-8 degrees Centigrade. In contrast to this natural variation, earth has been experiencing a rapid temperature increase over the past hundred years. There is ample scientific evidence from multiple sources that this is caused by the increase in carbon dioxide gas in the atmosphere, which has seen a 50% increase over the historical levels in just hundred years (Figure 2). Carbon dioxide is one of the greenhouse gases which traps heat from the sun and slows the natural cooling process of the earth. This increase of carbon dioxide is due to human activities: fossil fuel burning, industrial processes, deforestation, and agricultural practices. Ironically, those who suffer from the consequences did not contribute to these changes; those who did contribute are trying their best to convince the world that the temperature changes we see are natural, and nothing should be done. We must have no illusions that global warming is a human-caused phenomenon, and it has serious repercussions.

(See Figure 2. Global Temperature and Carbon Dioxide Levels)

Why should we care about global warming? Well, there are many reasons, but let us focus on earth’s water cycle. Middle schoolers know that water evaporates from the oceans, rises into the atmosphere where it cools, condenses, and falls back onto earth as rain or snow. When the oceans warm, the evaporation increases, and the warmer atmosphere can hold more water vapour. Water laden atmosphere results in severe and erratic weather. Ironically, water vapour is also a greenhouse gas, and this has a snowballing effect. The increased ocean temperature also disrupts ocean currents that influence the weather on land. The combined result is extreme and severe weather: violent storms and droughts depending on the geographic location. What is happening on the West coast of the USA is an example. The net result will be major departures from what is considered normal weather over millennia.

International organisations have been talking for 30 years about limiting global temperature increase to 1.5oC above pre-industrial levels by curtailing greenhouse gas emissions. But not much has been done and the temperature has risen by 1.2oC already. The challenge is that even if we can stop greenhouse gas emissions completely, right now, we have the problem of removing already existing 2,500 billion tons of carbon from the atmosphere, for which there are no practical solutions yet. Scientists worry about the consequences of runaway temperature increase and its effect on human life, which are many. It is not a doomsday prediction of life disappearing from earth, but a warning that life will be quite different from what humans are used to. All small tropical nations like ours are burdened with mitigating the consequences; in other words, get ready for more Ditwahs, do not wait for the twelve-day forecast.

Some opined that not enough warning was given regarding Ditwah; the truth is that the tools available for long-term prediction of the path or severity of a weather event (cyclone, typhoon, hurricane, tornado) are not perfect. There are multitude of rapidly changing factors contributing to the behavior of weather events. Meteorologists feed most up to date data to different computer models and try to identify the prediction with the highest probability. The multiple predictions for the same weather event are represented by what is known as spaghetti plots. Figure 3 shows the forecasted paths of a 2019 Atlantic hurricane five days ahead on the right and the actual path it followed on the left. While the long-term prediction of the path of a cyclone remains less accurate, its strength can vary within hours. There are several Indian ocean cyclones tracking sites online accessible to the public.

Figure 3. Forecasting vs Reality

There is no argument that short-term forecasts of this nature are valuable in saving lives and movable assets, but having long term plans in place to mitigate the effects of natural disasters is much more important than that. If a sizable section of the population must start over their lives from ground zero after every storm, how can a country economically develop?

The degree of our unpreparedness came to light during Ditwah disaster. It is not for lack of awareness; judging by the deluge of newspaper articles, blogs, vlogs, and speeches made, there is no shortage of knowledge and technical expertise to meet the challenge. The government has assured the necessary resources, and there is good reason to trust that the funds will be spent properly and not to line the pockets as happened during previous disasters. However, history tells us that despite the right conditions and good intentions, we could miss the opportunity again. Reasons for such skepticisms emerged during the few meetings the President held with the bureaucrats while visiting effected areas. Also, the COPE committee meetings plainly display the inherent inefficiencies and irregularities of our system and the absence of work ethics among all levels of the bureaucracy.

What it tells us is that we as a nation have an attitude problem. There are ample scholarly analyses by local as well as international researchers on this aspect of Sri Lankan psyche, and they label it as either island or colonial mentality. The first refers to the notion of isolated communities perceiving themselves as exceptional or superior to the rest of the world, and that the world is hell-bent on destroying or acquiring what they have. This attitude is exacerbated by the colonial mentality that promoted the divide and conquer rules and applied it to every societal characteristic imaginable; and plundered natural resources. As a result, now we are divided along ethnic, linguistic, religious, political, class, caste, geography, wealth, and many more real and imagined lines. Sadly, politicians, some religious leaders, and other opportunists keep inflaming these sentiments for their benefit when most of the population is willing to move on.

The first wish, therefore, is to get the strength, courage, and wisdom to think rationally, and discard outdated and outmoded belief systems that hinder our progress as a nation. May we get the courage to stop venerating elite who got there by exploiting the masses and the country’s wealth. More importantly, may we get the wisdom to educate the next generation to be free thinkers, give them the power and freedom to reject fabrications, myths, and beliefs that are not based on objective facts.

This necessitates altering our attitude towards many aspects of life. There is no doubt that free thinking does not come easily, it involves the proverbial ‘exterminating the consecrated bull.’ We are rightfully proud about our resplendent past. It is true that hydraulic engineering, art, and architecture flourished during the Anuradhapura period.

However, for one reason or another, we have lost those skills. Nowadays, all irrigation projects are done with foreign aid and assistance. The numerous replicas of the Avukana statue made with the help of modern technology, for example, cannot hold a candle to the real one. The fabled flying machine of Ravana is a figment of marvelous imagination of a skilled poet. Reality is that today we are a nation struggling with both natural and human-caused disasters, and dependent on the generosity of other nations, especially our gracious neighbor. Past glory is of little help in solving today’s problems.

Next comes national unity. Our society is so fragmented that no matter how beneficial a policy or an idea for the nation could be, some factions will oppose it, not based on facts, but by giving into propaganda created for selfish purposes. The island mentality is so pervasive, we fail to trust and respect fellow citizens, not to mention the government. The result is absence of long-term planning and stability. May we get the insight to separate policy from politics; to put nation first instead of our own little clan, or personal gains.

With increasing population and decreasing livable and arable land area, a national land management system becomes crucial. We must have an intelligent zoning system to prevent uncontrolled development. Should we allow building along waterways, on wetlands, and road easements? Should we not put the burden of risk on the risk takers using an insurance system instead of perpetual public aid programs? We have lost over 95% of the forest cover we had before European occupation. Forests function as water reservoirs that release rainwater gradually while reducing soil erosion and stabilizing land, unlike monocultures covering the hill country, the catchments of many rivers. Should we continue to allow uncontrolled encroachment of forests for tourism, religious, or industrial purposes, not to mention personal enjoyment of the elite? Is our use of land for agricultural purposes in keeping with changing global markets and local labor demands? Is haphazard subsistence farming viable? What would be the impact of sea level rising on waterways in low lying areas?

These are only a few aspects that future generations will have to grapple with in mitigating the consequences of worsening climate conditions. We cannot ignore the fact that weather patterns will be erratic and severe, and that will be the new normal. Survival under such conditions involves rational thinking, objective fact based planning, and systematic execution with long term nation interests in mind. That cannot be achieved with hanging onto outdated and outmoded beliefs, rituals, and traditions. Weather changes are not caused by divine interventions or planetary alignments as claimed by astrologers. Let us resolve to lay the foundation for bringing up the next generation that is capable of rational thinking and be different from their predecessors, in a better way.

by Geewananda Gunawardana

Features

From Diyabariya to Duberria: Lanka’s Forgotten Footprint in Global Science

For centuries, Sri Lanka’s biological knowledge travelled the world — anonymously. Embedded deep within the pages of European natural history books, Sinhala words were copied, distorted and repurposed, eventually fossilising into Latinised scientific names of snakes, bats and crops found thousands of kilometres away.

Africa’s reptiles, Europe’s taxonomic catalogues and global field guides still carry those echoes, largely unnoticed and uncredited.

Now, a Sri Lankan herpetologist is tracing those forgotten linguistic footprints back to their source.

Through painstaking archival research into 17th- and 18th-century zoological texts, herpetologist and taxonomic researcher Sanjaya Bandara has uncovered compelling evidence that several globally recognised scientific names — long assumed to be derived from Greek or Latin — are in fact rooted in Sinhala vernacular terms used by villagers, farmers and hunters in pre-colonial Sri Lanka.

“Scientific names are not just labels. They are stories,” Bandara told The Island. “And in many cases, those stories begin right here in Sri Lanka.”

Sanjaya Bandara

At the heart of Bandara’s work is etymology — the study of word origins — a field that plays a crucial role in zoology and taxonomy.

While classical languages dominate scientific nomenclature, his findings reveal that Sinhala words were quietly embedded in the foundations of modern biological classification as early as the 1700s.

One of the most striking examples is Ahaetulla, the genus name for Asian vine snakes. “The word Ahaetulla is not Greek or Latin at all,” Bandara explained. “It comes directly from the Sinhala vernacular used by locals for the Green Vine Snake.” Remarkably, the term was adopted by Carl Linnaeus himself, the father of modern taxonomy.

Another example lies in the vespertilionid bat genus Kerivoula, described by British zoologist John Edward Gray. Bandara notes that the name is a combination of the Sinhala words kiri (milky) and voula (bat). Even the scientific name of finger millet, Eleusine coracana, carries linguistic traces of the Sinhala word kurakkan, a cereal cultivated in Sri Lanka for centuries.

Yet Bandara’s most intriguing discoveries extend far beyond the island — all the way to Africa and the Mediterranean.

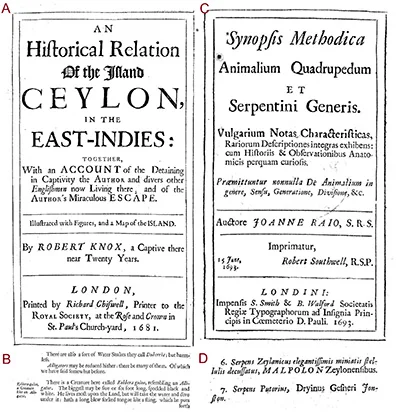

In a research paper recently published in the journal Bionomina, Bandara presented evidence that two well-known snake genera, Duberria and Malpolon, both described in 1826 by Austrian zoologist Leopold Fitzinger, likely originated from Sinhala words.

The name Duberria first appeared in Robert Knox’s 1681 account of Ceylon, where Knox refers to harmless water snakes called “Duberria” by locals. According to Bandara, this was a mispronunciation of Diyabariya, the Sinhala term for water snakes.

“Mispronunciations are common in Knox’s writings,” Bandara said. “English authors of the time struggled with Sinhala phonetics, and distorted versions of local names entered European literature.”

Over time, these distortions became formalised. Today, Duberria refers to African slug-eating snakes — a genus geographically distant, yet linguistically tethered to Sri Lanka.

Bandara’s study also proposes the long-overdue designation of a type species for the genus, reviving a 222-year-old scientific name in the process.

Equally compelling is the case of Malpolon, the genus of Montpellier snakes found across North Africa, the Middle East and southern Europe. Bandara traced the word back to a 1693 work by English zoologist John Ray, which catalogued snakes from Dutch India — including Sri Lanka.

“The term Malpolon appears alongside Sinhala vernacular names,” Bandara noted. “It is highly likely derived from Mal Polonga, meaning ‘flowery viper’.” Even today, some Sri Lankan communities use Mal Polonga to describe patterned snakes such as the Russell’s Wolf Snake.

Bandara’s research further reveals Sinhala roots in the African Red-lipped Herald Snake (Crotaphopeltis hotamboeia), whose species name likely stems from Hothambaya, a regional Sinhala term for mongooses and palm civets.

“These findings collectively show that Sri Lanka was not just a source of specimens, but a source of knowledge,” Bandara said. “Early European naturalists relied heavily on local names, local guides and local ecological understanding.”

Perhaps the most frequently asked question Bandara encounters concerns the mighty Anaconda. While not a scientific name, the word itself is widely believed to be a corruption of the Sinhala Henakandaya, another snake name recorded in Ray’s listings of Sri Lankan reptiles.

Perhaps the most frequently asked question Bandara encounters concerns the mighty Anaconda. While not a scientific name, the word itself is widely believed to be a corruption of the Sinhala Henakandaya, another snake name recorded in Ray’s listings of Sri Lankan reptiles.

“What is remarkable,” Bandara reflected, “is that these words travelled across continents, entered global usage, and remained there — often stripped of their original meanings.”

For Bandara, restoring those meanings is about more than taxonomy. It is about reclaiming Sri Lanka’s rightful place in the history of science.

“With this study, three more Sinhala words formally join scientific nomenclature,” he said.

“Who would have imagined that a Sinhala word would be used to name a snake in Africa?”

Long before biodiversity hotspots became buzzwords and conservation turned global, Sri Lanka’s language was already speaking through science — quietly, persistently, and across continents.

By Ifham Nizam

Features

Children first – even after a disaster

However, the children and their needs may be forgotten after a disaster.

Do not forget that children will also experience fear and distress although they may not have the capacity to express their emotions verbally. It is essential to create child-friendly spaces that allow them to cope through play, draw, and engage in supportive activities that help them process their experiences in a healthy manner.

The Institute for Research & Development in Health & Social Care (IRD), Sri Lanka launched the campaign, titled “Children first,” after the 2004 Tsunami, based on the fundamental principle of not to medicalise the distress but help to normalise it.

The Island picture page

The IRD distributed drawing material and play material to children in makeshift shelters. Some children grabbed drawing material, but some took away play material. Those who choose drawing material, drew in different camps, remarkably similar pictures; “how the tidal wave came”.

“The Island” supported the campaign generously, realising the potential impact of it.

The campaign became a popular and effective public health intervention.

“A public health intervention (PHI) is any action, policy, or programme designed to improve health outcomes at the population level. These interventions focus on preventing disease, promoting health, and protecting communities from health threats. Unlike individual healthcare interventions (treating individuals), which target personal health issues, public health interventions address collective health challenges and aim to create healthier environments for all.”

The campaign attracted highest attention of state and politicians.

The IRD continued this intervention throughout the protracted war, and during COVID-19.

The IRD quick to relaunch the “children first” campaign which once again have received proper attention by the public.

While promoting a public health approach to handling the situation, we would also like to note that there will be a significant smaller percentage of children and adolescents will develop mental health disorders or a psychiatric diagnosis.

We would like to share the scientific evidence for that, revealed through; the islandwide school survey carried out by the IRD in 2007.

During the survey, it was found that the prevalence of emotional disorder was 2.7%, conduct disorder 5.8%, hyperactivity disorder was 0.6%, and 8.5% were identified as having other psychiatric disorders. Absenteeism was present in 26.8%. Overall, previous exposure to was significantly associated with absenteeism whereas exposure to conflict was not, although some specific conflict-related exposures were significant risk factors. Mental disorder was strongly associated with absenteeism but did not account for its association with tsunami or conflict exposure.

During the survey, it was found that the prevalence of emotional disorder was 2.7%, conduct disorder 5.8%, hyperactivity disorder was 0.6%, and 8.5% were identified as having other psychiatric disorders. Absenteeism was present in 26.8%. Overall, previous exposure to was significantly associated with absenteeism whereas exposure to conflict was not, although some specific conflict-related exposures were significant risk factors. Mental disorder was strongly associated with absenteeism but did not account for its association with tsunami or conflict exposure.

The authors concluded that exposure to traumatic events may have a detrimental effect on subsequent school attendance. This may give rise to perpetuating socioeconomic inequality and needs further research to inform policy and intervention.

Even though, this small but significant percentage of children with psychiatric disorders will need specialist interventions, psychological treatment more than medication. Some of these children may complain of abdominal pain and headaches or other physical symptoms for which doctors will not be able to find a diagnosable medical cause. They are called “medically unexplained symptoms” or “somatization” or “bodily distress disorder”.

Sri Lanka has only a handful of specialists in child and adolescent psychiatric disorders but have adult psychiatrists who have enough experience in supervising care for such needy children. Compared to tsunami, the numbers have gone higher from around 20 to over 100 psychiatrists.

Most importantly, children absent from schools will need more close attention by the education authorities.

In conclusion, going by the principles of research dissemination sciences, it is extremely important that the public, including teachers and others providing social care, should be aware that the impact of Cyclone Ditwah, which was followed by major floods and landslides, which is a complex emergency impact, will range from normal human emotional behavioural responses to psychiatric illnesses. We should be careful not to medicalise this normal distress.

It’s crucial to recall an important statement made by the World Health Organisation following the Tsunam

Prof. Sumapthipala MBBS, DFM, MD Family Medicine, FSLCFP (SL), FRCPsych, CCST (UK), PhD (Lon)]

Director, Institute for Research and Development in Health and Social Care, Sri Lanka

Emeritus Professor of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, Faculty of Medicine & Health Sciences, Keele University, UK

Emeritus Professor of Global Mental Health, Kings College London

Secretary General, International society for Twin Studies

Visiting Professor in Psychiatry and Biomedical Research at the Faculty of Medicine, Kotelawala Defence University, Sri Lanka

Associate Editor, British Journal Psychiatry

Co-editor Ceylon Medical Journal.

Prof. Athula Sumathipala

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoMembers of Lankan Community in Washington D.C. donates to ‘Rebuilding Sri Lanka’ Flood Relief Fund

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoBritish MP calls on Foreign Secretary to expand sanction package against ‘Sri Lankan war criminals’

-

Features7 days ago

Features7 days agoGeneral education reforms: What about language and ethnicity?

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoSuspension of Indian drug part of cover-up by NMRA: Academy of Health Professionals

-

Sports5 days ago

Sports5 days agoChief selector’s remarks disappointing says Mickey Arthur

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoStreet vendors banned from Kandy City

-

Editorial7 days ago

Editorial7 days agoA very sad day for the rule of law

-

News7 days ago

News7 days agoUS Ambassador to Sri Lanka among 29 career diplomats recalled