Features

Revisiting the UNP’s Lost Generation: Reflections on Sri Lanka’s Recent Political History through the lens of Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha

By Avishka Mario Senewiratne,

Editor of The Ceylon Journal

Last December, Prof. Rajiva Wijesinha released a new book titled Ranil Wickremesinghe and the Emasculation of the United National Party. As the title suggests, the book tackles a contentious and provocative topic and may not be an easy read for everyone. Nevertheless, it presents a highly engaging and insightful narrative that warrants close attention. While much of the information may not be entirely new, the context and storytelling offer fresh perspectives and raise critical questions about Sri Lanka’s recent history.

The book is structured into four accessible chapters, with the first, titled “The Lost Generations of the UNP,” piquing interest by exploring important aspects of the party’s history that have often been overlooked. This article should be seen as a preliminary commentary on the first chapter. The chapter itself presents a series of short biographical sketches, focusing mainly on the political journeys of key figures within the United National Party (UNP), and how their careers were shaped by events such as assassination, early retirement, party defection, or resignation. However, the chapter could have been greatly improved with a brief historical overview of the UNP as an introduction. Founded in 1947, the UNP has often been referred to as the “Grand Old Party of Sri Lanka.” While it won the 1947 and 1952 elections, the party reached its lowest point in 1956, securing just eight seats in Parliament. In the 1950s, the UNP earned the nickname “Uncle Nephew Party,” a reference to the party’s perceived nepotism. Nevertheless, the UNP made notable comebacks in 1960 and again in 1965, after being in opposition from 1956 to 1965, except for the brief period between the March and July elections of 1960. In 1970, despite securing the plurality of the popular vote in the General Election, the UNP ended up with only 17 seats, leading Dudley Senanayake, the Prime Minister at the time, to take a backseat in the Opposition. This allowed J. R. Jayewardene to take control of the opposition, with Senanayake remaining the UNP leader.

After Dudley’s sudden death in 1973, Jayewardene assumed leadership of the party. In 1977, the UNP won a historic victory, securing a five sixths super majority in Parliament, reducing the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP) to just eight seats, and leaving the Leftist parties without representation. Under J. R. Jayewardene’s leadership, several skilled and effective politicians joined the Cabinet, which has been widely regarded as one of the most efficient in post-colonial Sri Lanka, particularly in managing the economy, fostering development, and strengthening foreign relations.

However, the Cabinet faced significant criticism for its handling of the ethnic conflict, which eventually led to a 26-year civil war. This issue has remained a central point of debate, overshadowing the Cabinet’s achievements. Between 1970 and 1977, the UNP lost some of its most well-known and renowned leaders such as Dudley Senanayake, M. D. Banda, U. B. Wanninayake, I. M. R. A. Iriyagolla, Paris Perera and V. A. Sugathadasa. C. P. de Silva, Philip Gunawardena, Murugesu Tiruchelvam Q. C. though not UNPers, but serving in the previous UNP regime’s Cabinet, passed away in the said period. Though elected in 1977, S. de S. Jayasinghe and Shelton Jayasinghe passed away within a year of the new government.

This left the UNP with a dominant senior member, J. R. Jayewardene, who was elected Prime Minister and then with the new Constitution, became the Executive President. There were hardly any other senior UNPers apart from Montague Jayawickrema, Edwin Hurulle and M. D. H. Jayawardene. Essentially, there was little internal opposition within the UNP to J. R. Jayewardene’s actions regarding the creation of a new constitution, the establishment of the executive presidency, the events surrounding the referendum and the many troubles of the 80s. The few who voiced dissent on these matters—M. D. H. Jayawardene and Dr. Neville Fernando—were compelled to resign from their positions well before the end of their terms.

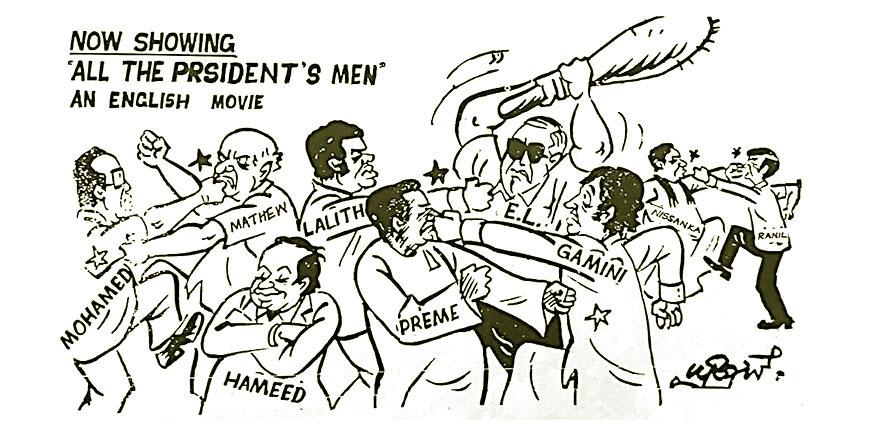

In this context, a new generation of politicians entered the UNP cabinet, bringing with them a blend of backgrounds and political experiences. Several key members of this cabinet are discussed in detail in Wijesinha’s first chapter on the “lost generation.” The 1977/78 UNP cabinets were notably diverse, with some members having roots in the SLFP, such as Gamini Dissanayake whose father had been a prominent SLFPer. Gamini himself first attempted to contest as a SLFPer in 1970. But upon his failing to get that that party’s ticket, he contested and won under the UNP. Ronnie de Mel, who had been aligned with the SLFP until 1975, was also a significant figure in this cabinet.

R. Premadasa, the Prime Minister, came from the Labour Party. The cabinet also included seasoned UNPer Wimala Kannangara, the only woman member, and Bill Devanayagam, the only Tamil representative, along with Shahul Hameed and M. H. Mohamed, the Muslim members. All four were entrusted with influential portfolios. Then there were newcomers to politics such as Nissanka Wijeyeratne, formerly of the Ceylon Civil Service who had fallen out with Mrs. Bandaranaike, and Lalith Athulathmudali, who had a flourishing legal practice.

The cabinet comprised a mix of old-fashioned UNPers, such as Maj. Montague Jayawickrema, Edwin Hurulle, E. L. Senanayake, Vincent Perera and Capt. C. P. J. Senewiratne, alongside more moderate figures like Anandatissa de Alwis, D. B. Wijetunga, Asoka Karunaratne, Gamini Jayasuriya, Ranjith Atapattu, and S. B. Herath. Cyril Mathew and Wijeyapala Mendis, more controversial figures, did not clearly fit into either category. Ranil Wickremasinghe, J. R. Jayewardene’s trusted nephew, remains today the sole surviving and active member of this Cabinet. Outside Parliament, Upali Wijewardena, who was speculated to enter both Parliament and the Cabinet before his disappearance in 1983, was another prominent figure. Abdul Bakeer Marker was made Speaker and later when E. L. Senanayke succeeded him, he became a Minister without a Portfolio. Though not a UNPer, S. Thondaman who was loyal to JR, found a Cabinet position as well.

Thus, JR Jayewardene’s cabinet was notably diverse, comprising individuals from varied political backgrounds, affiliations and experiences. As Wijesinha aptly notes, many of these figures were determined to pursue long political careers, with some even considered potential candidates for the presidency of Sri Lanka. What is particularly intriguing to the reader of Wijesinha’s first chapter are the significant, yet lesser-known aspects of the individuals discussed. It is questionable whether any political scientist, journalist, or historian has explored the perspectives and angles that Wijesinha addresses. Limited attention has been given to the ten individuals featured, including President Premadasa, whose biographies are often characterized by a somewhat romanticized portrayal or a hyper-critical portrait rather than a thorough, critical analysis.

Objectively speaking, all these individuals played vital roles in shaping modern Sri Lanka despite all controversy. Scholars should follow Wijesinha’s approach by critically examining and analyzing their subjects individually or collectively. Premadasa’s rise, first as Minister under Dudley Senanayake and later as Prime Minister under JR, is well-documented. Wijesinha concurs that Premadasa, with his appeal to the common man and success in programs like Gam Udawa, was the ideal candidate to succeed JR. Despite the challenges of the Civil War, the JVP insurrection, and internal party controversies, Premadasa oversaw significant economic growth. His assassination in 1993, just before his term’s end, curtailed his full potential.

One of the notable revelations in Wijesinha’s book, though not entirely undisclosed, is the power struggle among three prominent figures: Ronnie de Mel, Lalith Athulathmudali, and Upali Wijewardene. The former two were regarded as the most intellectually formidable members of J. R. Jayewardene’s Cabinet, and their rivalry was marked by intense animosity over policy matters and political positioning. Meanwhile, Upali Wijewardene, perceived as among the wealthiest individuals in the country at the time, was poised to enter the political arena. Ronnie de Mel achieved a significant milestone by balancing the national budget for eleven consecutive years, demonstrating a level of fiscal management unmatched by his predecessors or successors.

However, at the end of JR’s presidency, de Mel grew disillusioned with Ranasinghe Premadasa’s leadership and subsequently left the country. Although he returned to the legislature and remained politically active until 2004, he never recaptured the influence he once held under JR. Furthermore, JR’s most loyal confidante, Gamini Dissanayake, as noted by Wijesinha, initially expressed dissatisfaction with his assigned portfolio of “Irrigation, Power, and Highways.” Wijesinha’s father, Sam Wijesinha, who was then the Secretary General of the Parliament explained to the young Gamini the importance of his ministry that had been previously served by stalwarts like D. S., Dudley, Maithripala Senanayake and C. P. de Silva. Later, Gamini played a key role in implementing the Accelerated Mahaweli Development Project and in advancing Sri Lanka’s Test cricket status. Wijesinha also highlights Gamini’s presence in Jaffna in 1981 during the burning of the library, noting his subsequent shift toward a more moderate stance.

Lalith Athulathmudali, who held significant government portfolios, including Shipping and Trade and, later, National Security during the onset of the civil conflict, was regarded as one of the most respected politicians of his era. Wijesinghe notes that Lalith, an admirer of Singapore’s development, played a pivotal role in transforming the Colombo Port into one of the most efficient in Asia. Alongside Gamini Dissanayake, Lalith gained substantial popularity during the late 1970s and 1980s, fueling their aspirations for future presidential roles. By the end of 1988, however, it became evident that Premadasa was the leading contender to succeed JR. Both Lalith and Gamini supported Premadasa’s 1988 presidential campaign and hoping that one of them would be appointed Prime Minister in his administration. Instead, Premadasa appointed D. B. Wijetunga, causing significant discord within the UNP.

By 1991, escalating internal tensions led Lalith, Gamini, and other UNP backbenchers, in collaboration with the SLFP, to attempt to impeach President Premadasa. This effort ultimately failed, resulting in their exit from Parliament. Lalith and Gamini then created their own party. Tragically, Lalith was assassinated shortly before Premadasa, and Gamini (who had returned to the UNP) had a similar fate in 1994, just weeks before the presidential election in which he was the UNP’s candidate. Their untimely deaths ended two promising political careers.

Two individuals from Wijesinha’s “lost generation” are Dr. Ranjit Atapattu and Gamini Jayasuriya, both described by the author as “honest politicians” with similar temperaments. Atapattu was not assigned a significant portfolio until the 1982 cabinet reshuffle, when he became Minister of Health. Many would remember and acclaim that Atapattu was one of the most productive and enterprising Health Ministers of the 20th century. Despite his discomfort with some party policies, such as the Peace Accord with India, he remained loyal to the party and was later reappointed as Minister under Premadasa. However, he left politics in 1990 to join the UN, and as Wijesinha notes, his potential remained unfulfilled, with at least another decade of service left. Gamini Jayasuriya, a seasoned politician and direct descendant of Anagarika Dharmapala, with a strong streak of nationalism could not agree with JRJ’s Indo-Lankan Accord. Ever the gentleman, he resigned both from the cabinet and parliament in 1987 and never returned to politics.

Though Wijesinha names Shahul Hameed as one of those of “the lost generation”, both under JR and Premadasa, he received much prominence and died while serving an Opposition MP in 1999. It could be argued that he would have had a prominent role in the 2001-2004 UNP regime, had he lived.

B. Sirisena Cooray, a significant figure in the book, served as Mayor of Colombo for ten years during JR’s presidency but gained prominence only under Premadasa. A trusted confidante of Premadasa for nearly 40 years, Cooray became one of the most powerful ministers in his regime. Wijesinha observes that Cooray entered politics solely to support Premadasa, feeling no reason to remain active after the latter’s assassination. Wijesinha expresses his perspective on the various alleged conspiracies that Cooray was involved in during the 80s and 90s.

The author recounts a striking anecdote on page 20: “…when I went along with Chanaka (Amaratunga) to the funeral I was astonished to see what seemed an almost festive atmosphere. It was clear the senior leadership of the UNP felt no sorrow at all, and D. B. Wijetunga who was Acting President seemed more pleased at the advancement he had received than sad at the death of the man who had pushed him much higher than he deserved. And then Hema Premadasa made an extraordinary speech in which she seemed to be offering herself as her husband’s successor… as we were leaving, I noticed a man sitting by himself, tears pouring down his face. That, Chanaka, told me, was Sirisena Cooray, and I realized then that was a man of deep feeling, and his devotion to Premadasa was absolute.”

After Premadasa’s assassination, Cooray withdrew from active politics, even when he was offered the position of Prime Minister, resigning as UNP secretary, though his influence within the Colombo Municipality, as noted by Wijesinha, persisted well into the 21st century.

Dr. Gamini Wijesekera is another individual discussed by Wijesinha. As the author writes, he was less well-known then and is virtually forgotten today. Wijesekera was the General Secretary of the UNP and was a “gentleman”, who did not stoop into thuggery or corruption. A medical doctor turned politician, Wijesekera was one who played with a straight bat. He lost his first bid to parliament in a by-election in Maharagama in 1983. The winner of this election was Dinesh Gunawardena, who was heartily wished well by the defeated Wijesekera. As Wijesinha notes, Wijesekera later left the UNP disillusioned by some of its policies and formed Eksath Lanka Jathika Peramuna (ELJP) with Rukman Senanayake and A. C. Gooneratne. Wijesinha notes the interesting work of the ELJP, now a forgotten entity.

Fast forwarding to 1994, Wijesekera was back in the UNP camp and surprisingly replaced Sirisena Cooray as Secretary. In 1994, UNP lost its 17-year grip in power when the SLFP under Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga won narrowly in the General Election. However, three months later, Gamini Dissanayake was named the UNP candidate for the Presidency and ran an enthusiastic campaign, though CBK was eventually victorious. Wijesekera campaigned heavily for Dissanayake but ironically was one of the many prominent UNPers who perished in the Thotalanga bomb explosion with Gamini Dissanayake.

These were the ten individuals who Wijesinha examines as the “Lost Generation of the UNP”. A few others, who he hasn’t shed much light can be added to this list and dealt later by himself or another scholar. These include Dr. Neville Fernando, Shelton Ranaraja, M. D. H. Jayawardena as well as Ranjan Wijeyeratne and Harsha Abeywardena, who were assassinated. With all of these individuals, virtually losing their place in the UNP, it is not surprising that its next leader would be Wijesinha’s first cousin (mother’s brother’s son), Ranil Wickremasinghe, the subject of Wijesinha’s book, whom he discusses in length in the subsequent chapters of this book, which are not subject to this review. Just as JR became powerful in the 70s, his nephew Ranil Wickremasinghe had hardly any opposition within his Party.

Wijesinha’s approach is both engaging and accessible, skillfully combining anecdotal storytelling, humor, and incisive analysis. Due to his personal connections and familial ties with prominent figures of the UNP, most aspects of his account can be regarded as particularly reliable. This blend of narrative techniques contributes to a compelling story that captivates the reader, making his work not only enjoyable but also intellectually stimulating. The opening chapter of Rajiva Wijesinha’s book merits commendation for its content and narrative style. Moreover, it invites further research and publication on several related topics. For example, many political parties have formally or informally documented their histories.

Notable works in this regard include Prof. Wiswa Warnapala’s study of the Sri Lanka Freedom Party (SLFP), Leslie Goonawardena’s account of the Lanka Sama Samaja Party (LSSP), and Wijesinha’s own writings on the Liberal Party. These accounts, authored by prominent figures within their respective parties, naturally reflect their authors’ biases. However, the history and development of the UNP remains fragmented, with no comprehensive exploration undertaken either by Party members or external scholars. While Wijesinha has addressed this topic in part, a thorough and cohesive history of the UNP remains absent.

In this context, each of the individuals from the “lost generation” of Sri Lankan politics warrants a distinct and balanced biography. Additionally, projects such as the Mahaweli Development Scheme, the Greater Colombo Economic Commission, the Mahapola Scholarship Project, and Gam Udawa deserve scholarly scrutiny and analysis in future research. Should these suggestions be realized, they could significantly contribute to the literature essential for understanding a critical aspect of Sri Lanka’s recent history.

Features

The invisible crisis: How tour guide failures bleed value from every tourist

(Article 04 of the 04-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation)

(Article 04 of the 04-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation)

If you want to understand why Sri Lanka keeps leaking value even when arrivals hit “record” numbers, stop staring at SLTDA dashboards and start talking to the people who face tourists every day: the tour guides.

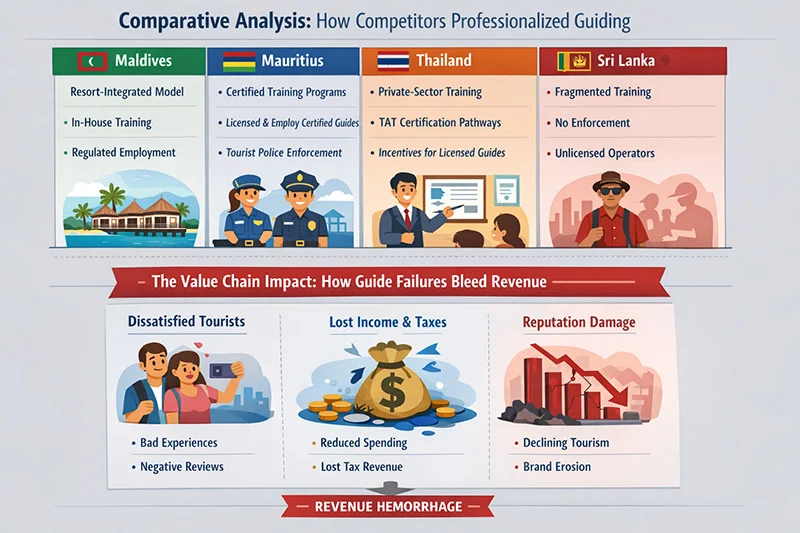

They are the “unofficial ambassadors” of Sri Lankan tourism, and they are the weakest, most neglected, most dysfunctional link in a value chain we pretend is functional. Nearly 60% of tourists use guides. Of those guides, 57% are unlicensed, untrained, and invisible to the very institutions claiming to regulate quality. This is not a marginal problem. It is a systemic failure to bleed value from every visitor.

The Invisible Workforce

The May 2024 “Comprehensive Study of the Sri Lankan Tour Guides” is the first serious attempt, in decades, to map this profession. Its findings should be front-page news. They are not, because acknowledging them would require admitting how fundamentally broken the system is. The official count (April 2024): SLTDA had 4,887 licensed guides in its books:

* 1,892 National Guides (39%)

* 1,552 Chauffeur Guides (32%)

* 1,339 Area Guides (27%)

* 104 Site Guides (2%)

The actual workforce: Survey data reveals these licensed categories represent only about 75% of people actually guiding tourists. About 23% identify as “other”; a polite euphemism for unlicensed operators: three-wheeler drivers, “surf boys,” informal city guides, and touts. Adjusted for informal operators, the true guide population is approximately 6,347; 32% National, 25% Chauffeur, 16% Area, 4% Site, and 23% unlicensed.

But even this understates reality. Industry practitioners interviewed in the study believe the informal universe is larger still, with unlicensed guides dominating certain tourist hotspots and price-sensitive segments. Using both top-down (tourist arrivals × share using guides) and bottom-up (guides × trips × party size) estimates, the study calculates that approximately 700,000 tourists used guides in 2023-24, roughly one-third of arrivals. Of those 700,000 tourists, 57% were handled by unlicensed guides.

Read that again. Most tourists interacting with guides are served by people with no formal training, no regulatory oversight, no quality standards, and no accountability. These are the “ambassadors” shaping visitor perceptions, driving purchasing decisions, and determining whether tourists extend stays, return, or recommend Sri Lanka. And they are invisible to SLTDA.

The Anatomy of Workforce Failure

The guide crisis is not accidental. It is the predictable outcome of decades of policy neglect, regulatory abdication, and institutional indifference.

1. Training Collapse and Barrier to Entry Failure

Becoming a licensed National Guide theoretically requires:

* Completion of formal training programmes

* Demonstrated language proficiency

* Knowledge of history, culture, geography

* Passing competency exams

In practice, these barriers have eroded. The study reveals:

* Training infrastructure is inadequate and geographically concentrated

* Language requirements are inconsistently enforced

* Knowledge assessments are outdated and poorly calibrated

* Continuous professional development is non-existent

The result: even licensed guides often lack the depth of knowledge, language skills, or service standards that high-yield tourists expect. Unlicensed guides have no standards at all. Compare this to competitors. In Mauritius, tour guides undergo rigorous government-certified training with mandatory refresher courses. The Maldives’ resort model embeds guide functions within integrated hospitality operations with strict quality controls. Thailand has well-developed private-sector training ecosystems feeding into licensed guide pools.

2. Economic Precarity and Income Volatility

Tour guiding in Sri Lanka is economically unstable:

* Seasonal income volatility: High earnings in peak months (December-March), near-zero in low season (April-June, September)

* No fixed salaries: Most guides work freelance or commission-based

* Age and experience don’t guarantee income: 60% of guides are over 40, but earnings decline with age due to physical demands and market preference for younger, language-proficient guides

* Commission dependency: Guides often earn more from commissions on shopping, gem purchases, and restaurant referrals than from guiding fees

The commission-driven model pushes guides to prioritise high-commission shops over meaningful experiences, leaving tourists feeling manipulated. With low earnings and poor incentives, skilled guides exist in the profession while few new entrants join. The result is a shrinking pool of struggling licensed guides and rising numbers of opportunistic unlicensed operators.

3. Regulatory Abdication and Unlicensed Proliferation

Unlicensed guides thrive because enforcement is absent, economic incentives favour avoiding fees and taxes, and tourists cannot distinguish licensed professionals from informal operators. With SLTDA’s limited capacity reducing oversight, unregistered activity expands. Guiding becomes the frontline where regulatory failure most visibly harms tourist experience and sector revenues in Sri Lanka.

4. Male-Dominated, Ageing, Geographically Uneven Workforce

The guide workforce is:

* Heavily male-dominated: Fewer than 10% are women

* Ageing: 60% are over 40; many in their 50s and 60s

* Geographically concentrated: Clustered in Colombo, Galle, Kandy, Cultural Triangle—minimal presence in emerging destinations

This creates multiple problems:

* Gender imbalance: Limits appeal to female solo travellers and certain market segments (wellness tourism, family travel with mothers)

* Physical limitations: Older guides struggle with demanding itineraries (hiking, adventure tourism)

* Knowledge ossification: Ageing workforce with no continuous learning rehashes outdated narratives, lacks digital literacy, cannot engage younger tourist demographics

* Regional gaps: Emerging destinations (Eastern Province, Northern heritage sites) lack trained guide capacity

1. Experience Degradation Lower Spending

Unlicensed guides lack knowledge, language skills, and service training. Tourist experience degrades. When tourists feel they are being shuttled to commission shops rather than authentic experiences, they:

* Cut trips short

* Skip additional paid activities

* Leave negative reviews

* Do not return or recommend

The yield impact is direct: degraded experiences reduce spending, return rates, and word-of-mouth premium.

2. Commission Steering → Value Leakage

Guides earning more from commissions than guiding fees optimise for merchant revenue, not tourist satisfaction.

This creates leakage: tourism spending flows to merchants paying highest commissions (often with foreign ownership or imported inventory), not to highest-quality experiences.

The economic distortion is visible: gems, souvenirs, and low-quality restaurants generate guide commissions while high-quality cultural sites, local artisan cooperatives, and authentic restaurants do not. Spending flows to low-value, high-leakage channels.

3. Safety and Security Risks → Reputation Damage

Unlicensed guides have no insurance, no accountability, no emergency training. When tourists encounter problems, accidents, harassment, scams, there is no recourse. Incidents generate negative publicity, travel advisories, reputation damage. The 2024-2025 reports of tourists being attacked by wildlife at major sites (Sigiriya) with inadequate safety protocols are symptomatic. Trained, licensed guides would have emergency protocols. Unlicensed operators improvise.

4. Market Segmentation Failure → Yield Optimisation Impossible

High-yield tourists (luxury, cultural immersion, adventure) require specialised guide-deep knowledge, language proficiency, cultural sensitivity. Sri Lanka cannot reliably deliver these guides at scale because:

* Training does not produce specialists (wildlife experts, heritage scholars, wellness practitioners)

* Economic precarity drives talent out

* Unlicensed operators dominate price-sensitive segments, leaving limited licensed capacity for premium segments

We cannot move upmarket because we lack the workforce to serve premium segments. We are locked into volume-chasing low-yield markets because that is what our guide workforce can provide.

The way forward

Fixing Sri Lanka’s guide crisis demands structural reform, not symbolic gestures. A full workforce census and licensing audit must map the real guide population, identify gaps, and set an enforcement baseline. Licensing must be mandatory, timebound, and backed by inspections and penalties. Economic incentives should reward professionalism through fair wages, transparent fees, and verified registries. Training must expand nationwide with specialisations, language standards, and continuous development. Gender and age imbalances require targeted recruitment, mentorship, and diversified roles. Finally, guides must be integrated into the tourism value chain through mandatory verification, accountability measures, and performancelinked feedback.

The Uncomfortable Truth

Can Sri Lanka achieve high-value tourism with a low-quality, largely unlicensed guide workforce? The answer is NO. Unambiguously, definitively, NO. Sri Lanka’s guides shape tourist perceptions, spending, and satisfaction, yet the system treats them as expendable; poorly trained, economically insecure, and largely unregulated. With 57% of tourists relying on unlicensed guides, experience quality becomes unpredictable and revenue leaks into commission-driven channels.

High-yield markets avoid destinations with weak service standards, leaving Sri Lanka stuck in low-value, volume tourism. This is not a training problem but a structural failure requiring regulatory enforcement, viable career pathways, and a complete overhaul of incentives. Without professionalising guides, high-value tourism is unattainable. Fixing the guide crisis is the foundation for genuine sector transformation.

The choice is ours. The workforce is waiting.

This concludes the 04-part series on Sri Lanka’s tourism stagnation. The diagnosis is complete. The question now is whether policymakers have the courage to act.

For any concerns/comments contact the author at saliya.ca@gmail.com

(The writer, a senior Chartered Accountant and professional banker, is Professor at SLIIT, Malabe. The views and opinions expressed in this article are personal.)

Features

Recruiting academics to state universities – beset by archaic selection processes?

Time has, by and large, stood still in the business of academic staff recruitment to state universities. Qualifications have proliferated and evolved to be more interdisciplinary, but our selection processes and evaluation criteria are unchanged since at least the late 1990s. But before I delve into the problems, I will describe the existing processes and schemes of recruitment. The discussion is limited to UGC-governed state universities (and does not include recruitment to medical and engineering sectors) though the problems may be relevant to other higher education institutions (HEIs).

How recruitment happens currently in SL state universities

Academic ranks in Sri Lankan state universities can be divided into three tiers (subdivisions are not discussed).

* Lecturer (Probationary)

– recruited with a four-year undergraduate degree. A tiny step higher is the Lecturer (Unconfirmed), recruited with a postgraduate degree but no teaching experience.

* A Senior Lecturer can be recruited with certain postgraduate qualifications and some number of years of teaching and research.

* Above this is the professor (of four types), which can be left out of this discussion since only one of those (Chair Professor) is by application.

State universities cannot hire permanent academic staff as and when they wish. Prior to advertising a vacancy, approval to recruit is obtained through a mind-numbing and time-consuming process (months!) ending at the Department of Management Services. The call for applications must list all ranks up to Senior Lecturer. All eligible candidates for Probationary to Senior Lecturer are interviewed, e.g., if a Department wants someone with a doctoral degree, they must still advertise for and interview candidates for all ranks, not only candidates with a doctoral degree. In the evaluation criteria, the first degree is more important than the doctoral degree (more on this strange phenomenon later). All of this is only possible when universities are not under a ‘hiring freeze’, which governments declare regularly and generally lasts several years.

Problem type 1

– Archaic processes and evaluation criteria

Twenty-five years ago, as a probationary lecturer with a first degree, I was a typical hire. We would be recruited, work some years and obtain postgraduate degrees (ideally using the privilege of paid study leave to attend a reputed university in the first world). State universities are primarily undergraduate teaching spaces, and when doctoral degrees were scarce, hiring probationary lecturers may have been a practical solution. The path to a higher degree was through the academic job. Now, due to availability of candidates with postgraduate qualifications and the problems of retaining academics who find foreign postgraduate opportunities, preference for candidates applying with a postgraduate qualification is growing. The evaluation scheme, however, prioritises the first degree over the candidate’s postgraduate education. Were I to apply to a Faculty of Education, despite a PhD on language teaching and research in education, I may not even be interviewed since my undergraduate degree is not in education. The ‘first degree first’ phenomenon shows that universities essentially ignore the intellectual development of a person beyond their early twenties. It also ignores the breadth of disciplines and their overlap with other fields.

This can be helped (not solved) by a simple fix, which can also reduce brain drain: give precedence to the doctoral degree in the required field, regardless of the candidate’s first degree, effected by a UGC circular. The suggestion is not fool-proof. It is a first step, and offered with the understanding that any selection process, however well the evaluation criteria are articulated, will be beset by multiple issues, including that of bias. Like other Sri Lankan institutions, universities, too, have tribal tendencies, surfacing in the form of a preference for one’s own alumni. Nevertheless, there are other problems that are, arguably, more pressing as I discuss next. In relation to the evaluation criteria, a problem is the narrow interpretation of any regulation, e.g., deciding the degree’s suitability based on the title rather than considering courses in the transcript. Despite rhetoric promoting internationalising and inter-disciplinarity, decision-making administrative and academic bodies have very literal expectations of candidates’ qualifications, e.g., a candidate with knowledge of digital literacy should show this through the title of the degree!

Problem type 2 – The mess of badly regulated higher education

A direct consequence of the contemporary expansion of higher education is a large number of applicants with myriad qualifications. The diversity of degree programmes cited makes the responsibility of selecting a suitable candidate for the job a challenging but very important one. After all, the job is for life – it is very difficult to fire a permanent employer in the state sector.

Widely varying undergraduate degree programmes.

At present, Sri Lankan undergraduates bring qualifications (at times more than one) from multiple types of higher education institutions: a degree from a UGC-affiliated state university, a state university external to the UGC, a state institution that is not a university, a foreign university, or a private HEI aka ‘private university’. It could be a degree received by attending on-site, in Sri Lanka or abroad. It could be from a private HEI’s affiliated foreign university or an external degree from a state university or an online only degree from a private HEI that is ‘UGC-approved’ or ‘Ministry of Education approved’, i.e., never studied in a university setting. Needless to say, the diversity (and their differences in quality) are dizzying. Unfortunately, under the evaluation scheme all degrees ‘recognised’ by the UGC are assigned the same marks. The same goes for the candidates’ merits or distinctions, first classes, etc., regardless of how difficult or easy the degree programme may be and even when capabilities, exposure, input, etc are obviously different.

Similar issues are faced when we consider postgraduate qualifications, though to a lesser degree. In my discipline(s), at least, a postgraduate degree obtained on-site from a first-world university is preferable to one from a local university (which usually have weekend or evening classes similar to part-time study) or online from a foreign university. Elitist this may be, but even the best local postgraduate degrees cannot provide the experience and intellectual growth gained by being in a university that gives you access to six million books and teaching and supervision by internationally-recognised scholars. Unfortunately, in the evaluation schemes for recruitment, the worst postgraduate qualification you know of will receive the same marks as one from NUS, Harvard or Leiden.

The problem is clear but what about a solution?

Recruitment to state universities needs to change to meet contemporary needs. We need evaluation criteria that allows us to get rid of the dross as well as a more sophisticated institutional understanding of using them. Recruitment is key if we want our institutions (and our country) to progress. I reiterate here the recommendations proposed in ‘Considerations for Higher Education Reform’ circulated previously by Kuppi Collective:

* Change bond regulations to be more just, in order to retain better qualified academics.

* Update the schemes of recruitment to reflect present-day realities of inter-disciplinary and multi-disciplinary training in order to recruit suitably qualified candidates.

* Ensure recruitment processes are made transparent by university administrations.

Kaushalya Perera is a senior lecturer at the University of Colombo.

(Kuppi is a politics and pedagogy happening on the margins of the lecture hall that parodies, subverts, and simultaneously reaffirms social hierarchies.)

Features

Talento … oozing with talent

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

This week, too, the spotlight is on an outfit that has gained popularity, mainly through social media.

Last week we had MISTER Band in our scene, and on 10th February, Yellow Beatz – both social media favourites.

Talento is a seven-piece band that plays all types of music, from the ‘60s to the modern tracks of today.

The band has reached many heights, since its inception in 2012, and has gained recognition as a leading wedding and dance band in the scene here.

The members that makeup the outfit have a solid musical background, which comes through years of hard work and dedication

Their portfolio of music contains a mix of both western and eastern songs and are carefully selected, they say, to match the requirements of the intended audience, occasion, or event.

Although the baila is a specialty, which is inherent to this group, that originates from Moratuwa, their repertoire is made up of a vast collection of love, classic, oldies and modern-day hits.

The musicians, who make up Talento, are:

Prabuddha Geetharuchi:

(Vocalist/ Frontman). He is an avid music enthusiast and was mentored by a lot of famous musicians, and trainers, since he was a child. Growing up with them influenced him to take on western songs, as well as other music styles. A Peterite, he is the main man behind the band Talento and is a versatile singer/entertainer who never fails to get the crowd going.

Geilee Fonseka (Vocals):

A dynamic and charismatic vocalist whose vibrant stage presence, and powerful voice, bring a fresh spark to every performance. Young, energetic, and musically refined, she is an artiste who effortlessly blends passion with precision – captivating audiences from the very first note. Blessed with an immense vocal range, Geilee is a truly versatile singer, confidently delivering Western and Eastern music across multiple languages and genres.

Chandana Perera (Drummer):

His expertise and exceptional skills have earned him recognition as one of the finest acoustic drummers in Sri Lanka. With over 40 tours under his belt, Chandana has demonstrated his dedication and passion for music, embodying the essential role of a drummer as the heartbeat of any band.

Harsha Soysa:

(Bassist/Vocalist). He a chorister of the western choir of St. Sebastian’s College, Moratuwa, who began his musical education under famous voice trainers, as well as bass guitar trainers in Sri Lanka. He has also performed at events overseas. He acts as the second singer of the band

Udara Jayakody:

(Keyboardist). He is also a qualified pianist, adding technical flavour to Talento’s music. His singing and harmonising skills are an extra asset to the band. From his childhood he has been a part of a number of orchestras as a pianist. He has also previously performed with several famous western bands.

Aruna Madushanka:

(Saxophonist). His proficiciency in playing various instruments, including the saxophone, soprano saxophone, and western flute, showcases his versatility as a musician, and his musical repertoire is further enhanced by his remarkable singing ability.

Prashan Pramuditha:

(Lead guitar). He has the ability to play different styles, both oriental and western music, and he also creates unique tones and patterns with the guitar..

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoJamming and re-setting the world: What is the role of Donald Trump?

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoAn innocent bystander or a passive onlooker?

-

Features2 days ago

Features2 days agoBrilliant Navy officer no more

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoRatmalana Airport: The Truth, The Whole Truth, And Nothing But The Truth

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoSri Lanka – world’s worst facilities for cricket fans

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoIRCSL transforms Sri Lanka’s insurance industry with first-ever Centralized Insurance Data Repository

-

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoAn efficacious strategy to boost exports of Sri Lanka in medium term

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoOverseas visits to drum up foreign assistance for Sri Lanka