Features

Rani’s struggle and pight of many mothers

by Anushka Kahandagamage

Unlike Manorani, mothers in both the North and South, whose children disappeared, had no means of reaching out to a state minister in the dead of night, begging for help or even sharing the devastating news of their children’s abduction. They did not have the privilege of calling on influential figures to intervene in their grief. This contrast does not lessen my empathy for Manorani, but rather highlights that a mother’s pain is universal, despite societal divisions or hierarchies. A thought that has been occupying my mind since the making of Rani is why a film is being made about Manorani when so many mothers in this country have lost their children. As Malathi de Alwis highlights, many women involved in the Mothers’ Front never had the chance to take the stage, which was controlled by men. Malathi also argues that Manorani’s special opportunity on that stage was due to her professional background as a medical doctor and her elite status.

Powerful Cinematic Experience

Rani, undoubtedly a powerful cinematic experience, left me frozen, its impact lingering within me. It took me back to the 1987-89 period, a time of terror, when I was just a first grader. The trauma from that era has stayed with our generation ever since. The film brought back events that were slowly fading from my memory, yet still lingered in my nightmares.

Challenging the official memory

Handagama and others involved in the making of the film succeeded in bringing a dark period, which was absent from history books, into the public consciousness or I would say, to the popular discourse. The official memory crafted by the then government regarding this horrifying chapter of history is mostly one-sided, glorifying the rulers while carefully erasing stories that do not align with their narrative. The film uncovers the painful truths, complicating the official narrative constructed by the government. It reveals that history is far more intricate than the simplified version presented in state-crafted accounts.

Subtitles

Creating a film about a dark chapter of the past, one that isn’t recorded in history books, and making it resonate with the public is a formidable challenge. However, the increasing number of people attending the film is a testament to its success. A common challenge faced by artistic films or those addressing complex social issues is their lack of popularity, which often prevents them from entering collective memory. Yet, Rani has effectively overcome this obstacle, achieving both widespread attention and relevance. While the film has undoubtedly succeeded in establishing itself within popular discourse and bringing attention to a dark, often overlooked period in history, the absence of Sinhala and Tamil subtitles presents a significant drawback. These subtitles would have made the film more accessible to a broader audience, particularly those who are directly impacted by the events depicted. Without them, a large segment of the population, including Sinhala and Tamil speakers, may have found it difficult to fully engage with the content and its emotional depth. Subtitles could have enriched the film’s reach and impact, fostering a deeper understanding of the complex and painful history that the movie seeks to bring to light.

Female protagonist

Making a woman the protagonist is an essential reflection of contemporary demands in cinema. Across the globe, there has been a significant shift toward promoting gender equality in film, with an increasing emphasis on strong, multifaceted female characters. This demand is not only a response to the changing social dynamics but also an effort to give a voice to women whose stories have often been sidelined in mainstream narratives. The focus on female protagonists ensures that audiences see a more balanced and inclusive reflection of society on screen.

The Ending and Accountability

The film would have had a more impactful conclusion if it had ended with the peaceful scene of the two women and the child on the beach. This moment was emotionally powerful and seemed like the natural conclusion to the story. However, the final sequence where the police officers are in their casual clothes, drunk and plotting the abduction of Richard, drags on far too long and felt like forcefully imposed. Instead of taking the audience to a peaceful ending, it inadvertently starts to irritate the audience due to its excessive length, detracting from the overall emotional tone of the film. As previously mentioned, the prolonged nature of this scene feels unnecessary and could have been condensed or omitted to maintain the film’s pace and emotional resonance.

In this final scene, perhaps the filmmaker intended to highlight the multiplicity of narratives (as is common in the post-modern era), but it fails in many ways. I strongly object to this scene, as it makes the rulers unaccountable for the murders and reduces the event to a toxic masculine portrayal of the police officers involved.

Features

“Independent” Prosecutor’s Office: Myth and Reality

By Professor G. L. Peiris

By Professor G. L. Peiris

D. Phil. (Oxford), Ph. D. (Sri Lanka);

Quondam Visiting Fellow of the Universities of Oxford, Cambridge and London;

Former Vice-Chancellor and Emeritus Professor of Law of the University of Colombo.

I. A Cornerstone of the Legal System

The institution of criminal proceedings is of vital concern to the public. Irrespective of the outcome of proceedings, subjection of a citizen to criminal litigation is fraught with grave consequences, including psychological trauma and impairment of social reputation, quite apart from the expenditure incurred in defending a criminal action.

The law, therefore, goes to considerable lengths to ensure that recourse to criminal proceedings is the sequel to an informed and well-structured process which includes careful consideration of available evidence in a spirit of independence and detachment, far removed from partisan considerations.

II. The Role of the Attorney-General

In our legal system this responsibility belongs to the Attorney-General: it is for him to bring his mind to bear on the entirety of material emanating from police investigations and to make a dispassionate judgment whether the evidence at his disposal, in the surrounding circumstances, warrants the commencement of criminal proceedings.

The solemnity of this burden is underlined by the traditional formulation, in decided cases in our country as well as in other jurisdictions, that the Attorney-General, in performing this function, acts in a quasi-judicial capacity.

This calls for a clear separation of his mindset from that appropriate to the discharge of his other responsibilities. The principal law officer of the Republic, he is the chief advisor to the Government of Sri Lanka, and it frequently falls to his lot to defend, before the courts, senior representatives of the government in Fundamental Rights, writs and other proceedings.

Nevertheless, it is a sacred and inviolable principle that, when it comes to deciding whether criminal proceedings should be launched or, when once begun, should be discontinued, against any defendant or group of defendants, this decision should be demonstrably bereft of any tinge of political or other extraneous element.

This is one of the core values of the system of criminal justice in our country and, indeed, an indispensable pillar of the Rule of Law.

III. Ample Scope of Prosecutorial Discretion

A pivot of our law is the principle of vires or jurisdiction, which requires that a statutory power must necessarily be exercised by the authority on which it is conferred by the legislature.

This is the rationale of the concept of prosecutorial discretion vested in the Office of Attorney-General. Discretion to determine the sufficiency of grounds to institute a prosecution or forward an indictment is that of the Attorney-General alone, and any usurpation of that discretion strikes at the very foundation of the system.

IV. Limiting Criteria

This does not mean, however, that the Attorney-General’s discretion is total or absolute, and altogether beyond the reach of the courts.

It is a salutary feature of our law that Sri Lankan courts, buttressed by judicial experience elsewhere, have formulated a series of criteria which operate as the limits of this discretion and enable intervention, with due restraint, in a limited category of situations.

A trilogy of judicial pronouncements by the Court of Appeal of Sri Lanka(Sandresh Ravi Karunanayake v. Attorney-General CA/Writ/441/2021; Duminda Lanka Liyanage v. Attorney-General CA/Writ/323/2022); Nadun Chinthaka Wickramaratne v. Attorney-General CA/Writ/523/2024) have rendered yeoman service to our law in this regard. The value of this approach lies in its essential sense of balance.

These judgments, by Sobhitha Rajakaruna J., now establish with clarity the frontiers of judicial review in respect of prosecutorial discretion of the Attorney-General.

The applicability of judicial review, in this context, has been accepted unequivocally by our courts: Victor Ivan v. Sarath Silva, Attorney-General (1998) 1SLR 340.

Its ramifications straddle a variety of settings. Where, for instance, the initiation of criminal proceedings is entirely unsupported by any evidentiary basis, the indictment may be impugned in judicial review, by the writ of certiorari. In the relevant academic literature, in particular the writings of Professor Sri William Wade, it is identified as a jurisdictional flaw, in that action in the absence of evidence is considered to have been taken without jurisdiction.

Similarly, prosecutorial discretion exercised by the Attorney-General may be vitiated by a range of factors including plainly discernible bias indicative of mala fides, patent error, consideration of irrelevant matters or failure to consider relevant material, grave procedural illegality or irregularity during the decision-making process – blemishes which, severally or in combination, may amount to abuse of process and, therefore, a potential miscarriage of justice.

Recent trends in Commonwealth law suggest scope for expansion of the ambit of judicial review on the broad ground of palpable unreasonableness (in terms of the well-known Wednesbury test), but this is an extension to be effected sparingly.

While these grounds admit of adequate flexibility in relation to judicial review, there is need for uncompromising insistence on the exclusion of any form of political intervention, or even a well-founded suspicion of it, in the interest of preserving public confidence in the integrity of the prosecutorial process.

V. Contemporary Developments

In recent weeks there has been widespread interest in policy perspectives, and timely changes in the law, in this field.

These developments provide the backdrop to the media statement by the Ministry of Justice on 10 February regarding the proposed establishment of an “Independent Prosecutor’s Office”. What is contemplated, as an initial step, is the appointment of an “Expert Committee” to prepare a Concept Paper on which the views of civil society and the public will be invited.

The composition of the proposed Committee has been announced. It will consist of “1. The Attorney-General or two nominees of the Attorney-General; 2. The Secretary to the Ministry of Justice; 3. A senior judge in the judicial service; 4. The President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka or his nominee”.

While a committee, so constituted, may be appropriate for the preliminary task of suggesting the outlines of the concept, its personnel, clearly, cannot be involved in operationalising the idea, as it moves forward. The Secretary to the Ministry of Justice is a political functionary, subject to control by the Executive; a member of the Judiciary can play no part in decisions as to the suitability of instituting prosecutions; defending counsel in criminal prosecutions will be drawn from the unofficial Bar.

Sri Lanka had, at one time, a Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP). The experience of the Crown Prosecution Service in the United Kingdom offers valuable guidance. The Government’s proposal, however, seems to go beyond the appointment of a Director and to envisage a comprehensive prosecutorial mechanism coexisting with the Office of Attorney-General.

VI. Critical Policy Issues

A mere change of nomenclature offers no more than a superficial and unconvincing solution. The experience of the DPP in our country was not an altogether happy one and, in any case, lasted only a short time. If susceptibility of the Attorney-General’s Office to political pressure is the core issue, it is hardly circumvented by the proposed supplementary mechanism.

Many structural issues naturally arise: What are the lines of demarcation contemplated? The new Office, if it is to serve a useful purpose, must obviously enjoy substantial independence from the Attorney-General, but a complete severance of the nexus, in terms of coordination, is unrealistic.

What safeguards, not explicitly spelt out in relation to the Attorney-General’s Office, are intended to apply to the proposed new Office? Will the Office of the Independent Prosecutor be served by members of the Attorney-General’s Department? If so, how will clarity be achieved in the delineation of reporting obligations? How will overlapping and interlocking lines of authority be dealt with? Since it has been made clear that the Attorney-General’s Office per se, will survive the proposed innovation, will there be some measure of erosion of the Attorney-General’s constitutionally entrenched functions? If this is the case, a piecemeal approach will not be feasible.

These are complex issues which will no doubt engage the intense interest and vigilance of the public, as the proposed reforms move forward.

Features

Excellent Budget by AKD, NPP Inexperience is the Government’s Enemy

by Rajan Philips

President Anura Kumara Dissanayake has delivered an excellent first budget. It could easily be described as the best budget so far this century and presented in the most dire economic circumstances in Sri Lanka’s modern history. Following his consummate performance in parliament, the President waded into a post-budget forum and joined the country’s economic experts to “dissect new Govt’s maiden budget,” as headlined by the Daily FT, one of the sponsors of the event. Whether one agrees with him or not, there is no question that AKD has been listening to those who knows the subject, has diligently done his homework on the budget file, and knows what he is doing,.

The problem he faces is that he cannot be doing homework on every file for the entire government, and he must find a way to quickly address the collective inexperience of his cabinet. He should not let this inexperience become the enemy that kills the government from within. Hopefully, he will find a way to address this within the framework of the budget and in the delegation of ministerial responsibilities for its implementation.

Somewhere in the budget, the President refers to economic decentralization, to deconcentrate the top heavy Western Province. Unfortunately, the corollary of political decentralization could not find its place in the text. Equally important, the President should also pay attention to ‘cabinet federalisation’ (AJ Wilson’s description of one of DS Senanayake’s quite a few master traits), and more so as he moves ahead to implement the budget proposals.

Ultimately, the success of the budget will be measured in political terms. Read, electoral terms. AKD’s and NPP’s detractors will be winding themselves for political wrestling in the local and later the provincial council elections. The NPP could be expected to hold its ground, but not necessarily all two-thirds of it. It should not at all be strange if the NPP gains ground in the North and East even as it loses some of it in the South. To keep the inevitable losses to the minimum, the government must eschew any and all complacency, which, modifying Mao’s famous Redbook take on it, could be described as the enemy of elections.

Geopolitically, paraphrasing the French Marxist Regis Debray, the NPP government must have its overhead antennas fully alert, but its feet firmly planted on the ground in Sri Lanka. The government cannot avoid being distracted by the global tumults that Donald Trump is creating day in and day out. There will be ripples, even waves, around Sri Lanka depending on what the Modi government decides to do in India to harmonize with the Trump Administration in Washington. Even so, the government’s primary preoccupation in the context of the turmoil in America should be to protect for as long as possible Sri Lanka’s exports to the US which are significant for Sri Lanka’s forex earnings.

At the same time, and consistent with the budget objectives, even as it diversifies its exports the government must diversify its importers. For the next four years, as Trump unfolds his madness, there will be responsive realignments in the Global North even as there will be reconsolidations in the Global South. The NPP government will have to navigate Sri Lanka through these currents without being smothered by them.

There are of course the self-proclaimed Rajapaksa nationalists who want to hitch their broken political wagons in Sri Lanka to the passing hegemon in America. They are in fact ethno-narcissists just like – but writ-small – the racial narcissist that Trump is. Ridiculous as these forces and their politics might seem, indeed as they are, the government should not underestimate their potential to do harm even by accident. Look at Bangladesh to see how political fortunes can dissipate fast, even though the NPP government is in no way comparable to Sheikh Hasina’s rotten government. The eternal home truth is the quick rise and the quicker fall of Gotabaya Rajapaksa.

Setting the Budget Context

The budget speech outlines as its backdrop the 2022 economic crisis that has now become the Rajapaksa era legacy, and as its context the overwhelming verdict of the people in the 2024 presidential and parliamentary elections. In this context, the President calls the budget both “historic” and “challenging,” because the government has to not only lay the foundation for fulfilling the people’s aspirations, but also to dispel “the wrongful picture (of us) created by the myths and malicious political propaganda against our economic policy and vision.” “We have succeeded in that,” the President asserted.

The government has proved its expectant critics wrong and stabilized the economy. All the indicators confirm that – the relatively stable exchange rate at one USD for LKR 300, and not LKR 400 as recklessly scare mongered; the lowering of the Treasury bill rate (8.8%) and getting inflation under control; forex reserves rising past USD six billion; finalizing agreements over debt-restructuring; and most of all keeping essential goods available and avoiding queues. In fairness, the credit for starting the process of economic stabilization belongs to Ranil Wickremesinghe, but post-election expectations in political circles have been that things will start to unravel due to NPP’s inexperience and even incompetence. That did not happen, and President AKD and the NPP government are justified in claiming credit for it.

Mr. Wickremesinghe may have even fancied that another economic crisis this time under an NPP government would give him a second kick at the can of power. No such luck. RW is now part of a team of exes – former ministers and presidents including Maithripala Sirisena – trying to figure out a way to stay relevant in today’s politics. Looking at this aging crowd outside parliament and its slightly younger version in the opposition within parliament, the NPP might fancy its chances of retaining power for more than one cycle of elections. But what the NPP has to contend with ultimately will not be ill equipped politicians but a frustrated electorate.

Apart from President AKD’s versatile feats, the NPP government has little to show to keep the people contented. Recurring rice shortage, the shortfall in coconuts, and the power outage blamed on a monkey tripping off a transformer have certainly taken the shine off the government. Looked from the other end, rice, coconuts and the power outage seem to the only shortcomings that the government is being picked on by media pundits and the political class. But what should concern the NPP government is that any one of them (rice, coconut or power), all of them together, or any similar shortages or failures, are enough to rile the people and bring down a government. Not long ago, it was called aragalaya.

Budget as Political Reset

The budget speech lays down the principles underlying the government’s approach to the economy: sectoral growth sustained by participation and even distribution on the supply side; and balancing roles for the market and the government on the demand side. A GDP growth rate of 5% is targeted for the medium term, predicated on a strong export sector performance while maintaining price stability and ensuring social welfare. Promoting investments, leveraging logistics, revamping tourism, digital transformation of the economy, and unleashing SME potentials through new credit structures are highlighted as the main growth poles. Allocations for health, education, food security, and social benefits are intended to rebuild and strengthen country’s social welfare system.

There is emphasis on Regional Development, including the assurance of special programmes for the Eastern Province, the Malayaga Tamils, and the Northern Province, but there is no mention of Provincial Councils and Local Government bodies and their agency roles in regional development. Regional industrial zones are identified including the promotion of Chemical Manufacturing in Paranthan, KKS and Mankulam in the Northern Province, Galle in the South and Trincomalee in the East. If some of them were to materialize the North and East might be seeing state sponsored industrial activity after more than 70 years when GG Ponnamabalam was Minister of Industries and Fisheries.

Auto Parts and Rubber Products manufacturing is also identified for promotion through industrial zones. What is not clearly indicated is whether new regional industrial initiatives will be tied to the export sector without which they may not be viable, as past experience has shown. Also, on the export front there is no identification of specific products and target markets to match the significant export sector growth that is being championed. Generally, for industries, there should be guardrails for minimizing and mitigating adverse environmental effects.

The budget rightly focuses on the modernization of public transport. Specific projects are identified for bus transport in Colombo and for the rail sector, including the revamping and the extension of the KV Line, multi-modal transport terminal in Kandy, and the expansion of the Thambuththegama Railway Station to function as a hub for transporting agricultural products. Large scale transport projects and rail transport are invariably the responsibility of the central government, but bus transport operations including those in Colombo and Kandy are better assigned to provincial and even larger municipal governments.

The budget provides for settling the legacy debt of the Sri Lankan Airlines (SLA) in the hope that SLA would hereafter become a viable enterprise. For other SOEs, the budget is proposing the setting up of a Holding Company again with the hope of revitalizing the mostly under-performing State Owned Enterprises (SOEs). Whether this approach is motivated by patriotic sentiments or political calculations, there is little support for it from past experience, except for enterprises in the crucial servicing and energy sectors.

The budget gets quite specific in its proposals for the agricultural and food sectors, especially rice and coconuts. At long last, there is official admission at the highest level that there is no data and information system for the “entire value chain” from paddy production to rice consumption. There is no immediate solution to this except the assurance to find one through the ADB funded “Food Security Livelihood Emergency Assistance Project” and a related World Bank project.

Coconuts are easy to count and difficult to hide. Some 4,500 million nuts are the projected demand for 2030, with 2,700 for the coconut industry and 1,800 for household consumption – at one per household per day. The problem is with production and the budget is allocating money for high yielding seedlings to be used in a new Northern Coconut Triangle extending from the coconut rich Northwestern Province, recommended by the Coconut Research Institute and mirror imaging the long established Southern Coconut Triangle. Better later than never, even when it comes to nuts.

All in all, the budget provides a good framework for the NPP government to reset its political road map. To succeed, the resetting must involve delegations at the ministerial level and following through to local communities and political grassroots. Equally important will be the medium in between, and the challenge to the NPP government is in resurrecting and using the currently defunct provincial and local government agencies.

Features

The Murder of a Journalist

By Anura Gunasekera

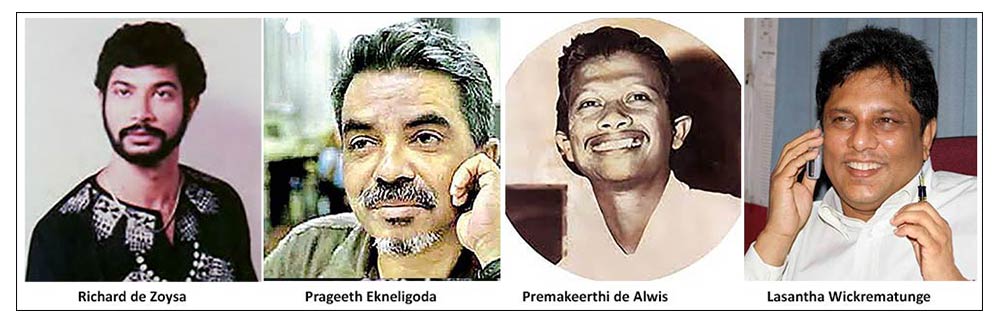

Commencing with Premakeerthi de Alwis in 1986 and concluding with Lasantha Wickrematunge in 2009, 40 accredited Sri Lankan journalists and media personnel, 31 of them of Tamil, have been murdered or died violently. Of these, 31 occurred between April 2004 and March 2009, during the Mahinda Rajapaksa tenure, initially as Prime Minister and then as President. His younger brother Gotabaya, later president himself, was the Defence Secretary of the country from 2005 to 2015.

During the above period, apart from those killed, many were abducted, assaulted and /or tortured, and intimidated in various other ways. A few left the country in fear of their lives. Most, if not all of those journalists, unsurprisingly, had been vocal critics of the government. With the defeat of the Rajapakse government in 2015, all harassment of journalists ceased, abruptly.

Of the above killings, those of Lasantha Wickrematunge (LW) and that of Richard de Zoysa in 1990, as well as the disappearance of Prageeth Ekneligoda in 2010 are, for a variety of reasons, not least the international outrage and condemnation, considered the most prominent. The most disturbing commonality across all these crimes is that none have been comprehensively investigated and the perpetrators punished.

In fact, despite pointers regarding the identity of the masterminds- circumstantial but compelling – and the very public nature of most of the actual incidents themselves, investigations have been either obstructed or stifled, through intimidation of potential witnesses, misleading autopsies, the enthusiastic pursuit of patently false lines of investigation, deliberately disingenuous official statements and, not infrequently, the suppression or disappearance of physical evidence.

The murder of Richard de Zoysa is again in the limelight on account of the recent film, “Rani”, although any hope of the crime being solved is almost zero. The murder of LW has been publicly profiled in the last few weeks, due to the order for the discharge, by the Attorney General (AG), of three suspects linked to events consequent to the murder, on the grounds of insufficient evidence.

Since the murder of LW, four successive governments have assured the country and the international community, that the case would be comprehensively investigated and those responsible punished. The slain Lasantha Wickrematunge had become an international metaphor for delayed justice. The present NPP government, led by president Anura Kumara Dissanayake, made the investigation of previously unsolved crimes, including that of Lasantha’s murder, and the cleansing of corrupt government systems, a cornerstone of its election manifesto. The sweeping victory of the NPP at the recent general elections was largely due to the faith that the electors placed in those promises.

Why is the case of Lasantha Wickrematunge so important?

Investigative Journalists play a vital role in maintaining a free and open society, by providing the public with critical information, holding power to account and exposing corruption and injustice. In that context, LW played a major role through his paper, “The Sunday Leader” which, week after week, exposed the massive corruption within the Rajapaksa regime, citing specific transactions and quite often linking acts of malfeasance to then President Mahinda Rajapaksa, his brother and Defence Secretary Gotabaya, or to close associates of the Rajapaksa family and the regime.

LW’s silence was worth more to the Rajapaksa family in particular, than to anybody else in the country. In fact, LW’s murder was apparently preceded by an unsuccessful attempt, in 2007, by Mahinda Rajapaksa himself, to broker the sale of the paper to an investor of his choice, the offer being made to Lal, LW’s brother (Page 234- Unbowed and Unafraid- Raine Wickrematunge). The only possible reason for a president of a country to personally seek the divestment of ownership of an outspoken newspaper, is control of its narrative content and direction.

Two years later Lasantha’s assassination paved the way for the exercise of this option.

In Sept 2012, businessman and alleged Rajapakse associate, Asanga Seneviratne, many of whose property development and investment deals had been criticized at various times by the “Leader”, bought a 72% stake in the “Leader” and its sister newspaper, “Iruresa”. In the same month Frederica Jansz, then editor of the “Leader” and long-time colleague of LW, was summarily dismissed from her position. In May 2015 the “Leader”, now under a decidedly Rajapaksa-friendly dispensation, tendered an unconditional apology to Gotabaya Rajapksa for a series of articles it had run, during LW’s tenure as editor, on the indisputably questionable method of purchase of MiG-27 aircraft from Ukraine, for the Sri Lanka Air Force. Udayanga Weeratunga, relative of the Rajapaksa family, as then Sri Lanka’s ambassador to Ukraine, allegedly played a major role in facilitating the said transaction. According to Ahimsa, LW’s daughter, LW was on the verge of exposing the highly complex and sordid details of the deal in entirety, when he was murdered (The MiG deal; Why My Father Had To Die- Groundviews-01/08/21).

The above is just one of the hundreds of expose’s featured by LW and he very rarely got it wrong. Very few other journalists in recent decades – the late Victor Ivan was one other- so courageously and in such minute detail, addressed the sins of those in power as LW did. They were issues that many journalists avoided, a self-regulation on truthful journalism brought about as a conditioned survival mechanism, in response to the brutal repression of those who dared to write the truth about power.

LW’s last writing- “Then They Came For Me”– published posthumously and now a classic of Asian journalism, was a chillingly prophetic prediction of his own death, pointing an accusatory finger at his erstwhile friend, then president Mahinda Rajapaksa.

The death of any human being diminishes society but the death of a fearless journalist, who holds a mirror to the foibles of society and power, diminishes our world in a special way; especially a world such as ours where leaders, irrespective of political colour, have proved to be treacherous, unreliable, corrupt, mercenary and nepotistic.

On the 27th of January, Parinda Ranasinghe Jr, Attorney General (AG) of Sri Lanka, ordered the release – citing lack of evidence to proceed with indictments – of Ananda Udalagama, implicated in the abduction in August 2009 of Karunaratne Dias, LW’s driver, and DIG Prasanna Nanayakkara and Sub-inspector Sugathapala, both implicated in the disappearance of a notebook recovered from LW’s vehicle after his murder. Consequent to immediate and widespread criticism and physical demonstrations against this order, it has since been rescinded.

In this episode the primary, indisputable principle, is that it is entirely at the AG’s discretion, to decide whether or not to charge a suspect, taking in to account the validity of admissible evidence available, and the prospect of securing a conviction. The political body has no right suggest a review of such a decision, or to compel the AG to consider such a review, irrespective of the importance of the case. At the same time it is also assumed that the AG and his department will carry out their duties impartially, irrespective of past loyalties – if any – and current personal prejudices, especially in relation to sensational cases involving those previously and currently in power.

Assuming that the release order was issued after a comprehensive analysis of the available evidence, the subsequent reversal is baffling, to say the least. Is it that the AG, or the legal officers responsible, consequent to a re-assessment of available material, suddenly realized that they had a made a serious error of judgment? Or did the AG’s department cave in to political and public pressure and decide to change its decision?

If the AG had braved both public and political displeasure and held fast to the original decision, it would have been perfectly acceptable and even commendable. However, it is now being reported in responsible mainstream newspapers, that the rescinding of the original decision is a response to a request by the Criminal Investigation Department (CID), to give it more time to act on the AG’s order, on account of the controversy surrounding the issue. The official version now appears to be that what is now in place is a suspension of the original decision, and not a reversal.

In the meantime, Ahimsa, through her publicized letter of February 14 to Anura Meddegoda, President of the Bar Association of Sri Lanka, has censured him for his hypocritical support of the AG and his position in this episode. She has supported her position by reference to Meddegoda’s protest against a similar order by the AG, under very similar circumstances, when it involved the murder of one Indika Prasad, allegedly by members of the Special Task Force. The interests of the victim’s wife were represented by Meddegoda.

Ahimsa has condemned the AG’s position in this matter, in the said letter citing seemingly convincing evidence available against the three suspects named earlier. She has even called for the impeachment of the AG, on the grounds that in ordering the discharge of the suspects, he has deliberately chosen to ignore vital evidence.

For an ordinary citizen such as the writer, with only a minimal understanding of criminal law, an analysis of the legal validity of the AG’s management of the case in question is not possible. But, still, to the writer and to several million other citizens who helped to bring the NPP in to power, the delivery of justice in matters of public corruption, politically motivated murders and similar crimes, are issues of supreme importance.

Fearless journalists such as Lasantha Wickrematunge paid with their lives for their reportage and public exposure of the crimes of the politically powerful. The justice for such crimes is owed, not only to the family members of the slain, but to the nation itself. It ceased to be a private, Wickrematunge family project a long time ago.

President AKD has steadfastly maintained that his regime will not interfere with ongoing legal processes, unlike previous regimes which seemed to often guide the hand of the law, in cases which featured those in power, unfavourably. However, what may be prudent and necessary, if justice is to be finally done, is intervention and course correction at critical stages, to ensure that public officers entrusted with relevant responsibilities do not lose sight of both the principle and the objective.

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoCommercial High Court orders AASSL to pay Rs 176 mn for unilateral termination of contract

-

Sports4 days ago

Sports4 days agoSri Lanka face Australia in Masters World Cup semi-final today

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoUSAID and NGOS under siege

-

Features6 days ago

Features6 days agoDoing it in the Philippines…

-

Midweek Review5 days ago

Midweek Review5 days agoImpact of US policy shift on Sri Lanka

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoCourtroom shooting: Police admit serious security lapses

-

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDialog delivers strong FY 2024 performance with 10% Core Revenue Growth

-

News5 days ago

News5 days agoFSP lambasts Budget as extension of IMF austerity agenda at the expense of people