Features

Pension for politicians, for what service they do to the country?

Members of Parliament (MP) have to serve 10 years hereafter to qualify for pension as opposed to five years at present. (2022 Budget speech)

BY Dr. Sudath Gunasekara

While welcoming that policy decision of the Government, who can say that this is not another election ‘gundu’ to deceive the people aimed at the proposed Provincial Council Elections? If the Government was really honest and concerned about public good, what it should do is to abolish this joke immediately, particularly in view of the present hard times the country has fallen on, as Canada had done in 1995, without continuing an unwanted bonanza to trap politicians cunningly, used as a bait by party leaders, that bleed the nation.

The Mike Harris government eliminated MPPs’ pension plans following the 1995 provincial election. Even if it is allowed in exceptional cases like in Canada, a pension to a politician should be paid only after 65 years, in recognition of his or her distinguished service to the nation when they are disabled, to earn a living.

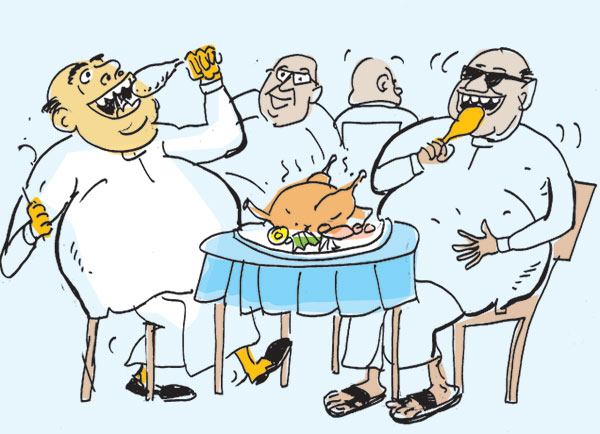

Why pay pensions to politicians at all, who volunteer and swear to serve the people at elections and on the contrary rob and destroy the entire nation after they come to power. It is to hoodwink.

Finance Minister Basil Rajapaksa in his Budget (2022) speech has proposed that MPs be eligible for a pension only after completing 10 years of continuous ‘service’. This too in my view is not warranted and justified at all, particularly in this country, where they come into politics for power and amass wealth and rob public assets and money in unethical ways. They don’t even declare their assets before nomination or even afterwards, deliberately, to enable themselves to justify their illegal earnings if someone questions their assets afterwards. What is more ludicrous is their claim to a pension, despite the enormous financial benefits and privileges afforded from the day they are elected, compared to what politicians in pre 70s got. For example, an MP those days got only an allowance of 500 rupees, a Junior Minister Rs 750 and a Minister Rs 1,000 a month. They were also not allocated official vehicles, duty-free vehicle permits, official residences in Colombo, other payments like sitting allowances or any other allowance or other perks like special allocations for seats, (in spite of the fact that none of these people have an electorate as they are only District MPs, which has made representative democracy a big farce).

My question is, under these circumstances, why pay a pension at all to any politician in this country. Because paying a pension to any politician is contrary to all basic principles, related to paying pensions, accepted all over the world. Because, originally people over 70 were paid a pension, who were unable to make a living, as a mark of gratitude for the continued and devoted service they rendered to the nation or a certain company. Those days it was public service and not self-service, as it is today.

The man behind the initiative called ‘The Old Age and Disability Bill’ was Otto von Bismarck of the German Empire. Germany was thus the first European country to establish a fully-fledged pensions scheme for workers aged 70 or above. The limit was lowered to 65 in June 1916.

In 1875, The American Express Co. created the first private pension plan in the US for the elderly and workers with disabilities. Early pension benefits were designed to pay out a relatively low percentage of the employee’s pay at retirement and were not designed to replace the employee’s full final income.

In Sri Lanka it was started by the colonial Government for the benefit of its aged employees, for the dedicated service they had rendered to the Empire. Subsequently it was extended to retired public servants who had completed 35 years of satisfactory service in public service. As such it was justifiable, as the only income of a man or a woman, who has devoted years in service to the nation, debarring any other job while one is engaged in public service, comes to an end the day he or she retires. But it should be noted that, to get that benefit they had to contribute a certain percentage monthly from their salary to which the Government contributed a certain percentage. Therefore, in fact, they are paid from a reserve fund maintained by the Government out of funds they have contributed throughout their service. What is more is that they have to complete 35 years of service to qualify for the pension. When someone retires prematurely the pension is frozen until he or she reaches the age of 55. This clearly shows that there is a very sound rationale behind paying a pension to a retired public servant and it is fully justified both rationally and ethically.

Now let us examine the rationale behind paying a pension to a politician in this country. Paying pensions to politicians started in 1977 by the JR Jayewardene Government. Curiously it was the first legal enactment of that so-called Democratic Socialist Government of JR, passed as a matter of priority, as if it was the most burning ‘public issue’ his government had to solve. Does this not show the degree of concern and commitment our politicians had towards the welfare of the people who elevated them to high positions by electing them with a 5/6th majority in 1977, hoping to get a better deal than from the previous government of Sirimavo Bandaranaike.

What is hilarious and despicable is that this piece of legislation marked the turning point in Sri Lankan political culture, when the interests of the politicians overtook those of the people in a country that inherited a rich legacy of public good enshrined in the Buddhist concept ‘Bahujana hitaya bahujana sukhaya’ (for the good of the many and for their happiness at large).

What is even more despicable is that it was awarded to all politicians who completed five years ‘service’ irrespective of whether they served the people or not. What was ludicrous was the payment of the pension to his or her spouse after the death of the MP. Further his family would get another pension or even more if his or her son or daughter had been appointed as the Private Secretary, Public Relations Officer or such, which has now become the norm, a tradition that had come to stay as a political privilege. Payment of pensions under this scheme was made with retrospective effect and it was payable even to politicians who served in the State Council, if they were living at that time, with arrears.

Only one man refused to accept this blood money, in the history of Parliament. He returned it to the Speaker. The man mentioned here was my good friend M.S. Themis, the third MP for Colombo Central in 1956. He was the first person and perhaps the only man to return it. I know it for certain as I was the one who prepared the cover letter to the Speaker.

This piece of legislation was also a complete violation of the Pension minute which nobody dared to challenge or even question up to date either in a court of law or Parliament, said to be the Supreme law-making body of the country.

Isn’t it interesting to note how our lawmakers make laws and for whose benefit they make them in this so-called supreme legislature of the country, expected to make laws for good governance for the good of the people and the good of the country at large?

JR did not stop at that. He did everything to enhance the fabulous benefit package to MPs with immediate effect. He dramatically increased salaries, increased the sitting allowance and official vehicles and duty-free vehicle permits were also provided, which they could sell in the open market and make a fabulous fortune. Official quarters in Colombo were also provided, whereas they had to be in Colombo only for eight days a month. Unlimited job permits for MPs to provide employment to their party supporters, monopoly of tavern licence, business permits and government contracts, nationalisation of land for a song, by Mrs B, through the establishment of Land Reform Commission (LRC); and government import permits; the sky was the limit to such privileges. Here I stop the list for brevity and lack of space. All this was done to buy over the MPs, to maintain the majority in Parliament, to embellish and consolidate JR’s dictatorial position as the Executive President which perhaps he thought was a lifetime job, but unfortunately not.

The same corrupt highway robbery still continues at increasing rates without being openly questioned or challenged by anyone in the ‘People’s Parliament’. So much so today the whole system of governance in this country has become a veritable national liability.

JR also increased the number of MPs in Parliament from 196 to 225 by introducing the National list, to provide a place in Parliament for their kith and kin and family friends, as backdoor MPs, bypassing elections, making Representative Parliament ‘Non-representative’, thereby rendering representative democracy a hilarious joke. Had it been reduced to the previous number, it would have saved billions for national development and reduced IMF and other foreign loan repayment burdens, thereby reducing the annual budget deficit and avoiding bankruptcy.

On top of this, JR also signed an agreement with Rajiv Gandhi, handing over the North and East, comprising 1/3 of the land of the country and 2/3 of the coastal belt, together with its maritime territory, as the Traditional Historical Homeland of the Tamil people.

What is more depressing is that this provincial council system has already wasted trillions of public funds for the upkeep of these superfluous new political establishments at no benefit to the country but only to the politicians, from 1987 to date. It is said that 85 percent of the national tax collection is spent on the upkeep of politicians and so-called public officials in this country, leaving only 15 percent to do everything else for over 21 million citizens. Meanwhile, lawlessness, corruption and international debt to the tune of US $ 56 billion, drags the country to the bottom of abject poverty and bankruptcy, forcing this once proud nation and second richest country in Asia, second only to Japan by 1948, to seek loans even from Bangladesh and Maldives.

This is the pathetic situation in to which this proud and rich nation, which gave Sterling loans even to the British Empire in the early 1950s, has been thrust, by our politicians who are supposed to have ruled this nation from 1948 up to date, a land further devastated by separatists Tamils and Muslims with their Tamil and Muslim dreamlands.

It is this kind of politicians, who have robbed the nation blind and continue to do so, who are responsible for making this country debt-ridden, while these parasitic and good-for-nothing governments continue to give fat pensions to MPs, extracting from the beggar’s bowl.

Against this backdrop, I strongly oppose a single cent being given to any politician, as a pension. In addition, I also suggest that all extraordinary benefits such as palatial official residences, official vehicles, security details and other benefits be withdrawn forthwith before the masses march in thousands and forcibly take over all these public assets as protest against what they have done to this country and the Sinhala nation over the past 73 years.

This includes all politicians including ex-Presidents and their rich widows. However, I am not against paying a pension to an honest politician like C.W.W Kannangara who devoted his entire life in service to the people and the country and who had done an indelible and memorable service to the nation, after passing a resolution in Parliament to that effect. That will definitely prevent self-seeking, wealth-mongering people in politics from receiving the pension, limiting it to men and women of outstanding character, dignity and commitment to the service of people, the noble vow of any honest politician.

Finally I propose first, the immediate abolition of the pension scheme to all politicians and second, appointment of a powerful Presidential or Public Commission to enquire into the illegal earnings of all politicians at all levels starting from 1977 up to date and confiscation of all assets proven illegal, both at home and abroad, such as ‘Pandora assets’. I propose that all that wealth be credited to the General Treasury Account so that people will get back all the wealth robbed by politicians at least from 1977 onwards, so that all those who aspire to be politicians in future will begin with a new political vision, opening the doors to a new political culture, setting a Sri Lankan model for the entire world and once again restore the ancient glory of the Sinhala nation.

Features

Theocratic Iran facing unprecedented challenge

The world is having the evidence of its eyes all over again that ‘economics drives politics’ and this time around the proof is coming from theocratic Iran. Iranians in their tens of thousands are on the country’s streets calling for a regime change right now but it is all too plain that the wellsprings of the unprecedented revolt against the state are economic in nature. It is widespread financial hardship and currency depreciation, for example, that triggered the uprising in the first place.

The world is having the evidence of its eyes all over again that ‘economics drives politics’ and this time around the proof is coming from theocratic Iran. Iranians in their tens of thousands are on the country’s streets calling for a regime change right now but it is all too plain that the wellsprings of the unprecedented revolt against the state are economic in nature. It is widespread financial hardship and currency depreciation, for example, that triggered the uprising in the first place.

However, there is no denying that Iran’s current movement for drastic political change has within its fold multiple other forces, besides the economically affected, that are urging a comprehensive transformation as it were of the country’s political system to enable the equitable empowerment of the people. For example, the call has been gaining ground with increasing intensity over the weeks that the country’s number one theocratic ruler, President Ali Khamenei, steps down from power.

That is, the validity and continuation of theocratic rule is coming to be questioned unprecedentedly and with increasing audibility and boldness by the public. Besides, there is apparently fierce opposition to the concentration of political power at the pinnacle of the Iranian power structure.

Popular revolts have been breaking out every now and then of course in Iran over the years, but the current protest is remarkable for its social diversity and the numbers it has been attracting over the past few weeks. It could be described as a popular revolt in the genuine sense of the phrase. Not to be also forgotten is the number of casualties claimed by the unrest, which stands at some 2000.

Of considerable note is the fact that many Iranian youths have been killed in the revolt. It points to the fact that youth disaffection against the state has been on the rise as well and could be at boiling point. From the viewpoint of future democratic development in Iran, this trend needs to be seen as positive.

Politically-conscious youngsters prioritize self-expression among other fundamental human rights and stifling their channels of self-expression, for example, by shutting down Internet communication links, would be tantamount to suppressing youth aspirations with a heavy hand. It should come as no surprise that they are protesting strongly against the state as well.

Another notable phenomenon is the increasing disaffection among sections of Iran’s women. They too are on the streets in defiance of the authorities. A turning point in this regard was the death of Mahsa Amini in 2022, which apparently befell her all because she defied state orders to be dressed in the Hijab. On that occasion as well, the event brought protesters in considerable numbers onto the streets of Tehran and other cities.

Once again, from the viewpoint of democratic development the increasing participation of Iranian women in popular revolts should be considered thought-provoking. It points to a heightening political consciousness among Iranian women which may not be easy to suppress going forward. It could also mean that paternalism and its related practices and social forms may need to re-assessed by the authorities.

It is entirely a matter for the Iranian people to address the above questions, the neglect of which could prove counter-productive for them, but it is all too clear that a relaxing of authoritarian control over the state and society would win favour among a considerable section of the populace.

However, it is far too early to conclude that Iran is at risk of imploding. This should be seen as quite a distance away in consideration of the fact that the Iranian government is continuing to possess its coercive power. Unless the country’s law enforcement authorities turn against the state as well this coercive capability will remain with Iran’s theocratic rulers and the latter will be in a position to quash popular revolts and continue in power. But the ruling authorities could not afford the luxury of presuming that all will be well at home, going into the future.

Meanwhile US President Donald Trump has assured the Iranian people of his assistance but it is not clear as to what form such support would take and when it would be delivered. The most important way in which the Trump administration could help the Iranian people is by helping in the process of empowering them equitably and this could be primarily achieved only by democratizing the Iranian state.

It is difficult to see the US doing this to even a minor measure under President Trump. This is because the latter’s principal preoccupation is to make the ‘US Great Once again’, and little else. To achieve the latter, the US will be doing battle with its international rivals to climb to the pinnacle of the international political system as the unchallengeable principal power in every conceivable respect.

That is, Realpolitik considerations would be the main ‘stuff and substance’ of US foreign policy with a corresponding downplaying of things that matter for a major democratic power, including the promotion of worldwide democratic development and the rendering of humanitarian assistance where it is most needed. The US’ increasing disengagement from UN development agencies alone proves the latter.

Given the above foreign policy proclivities it is highly unlikely that the Iranian people would be assisted in any substantive way by the Trump administration. On the other hand, the possibility of US military strikes on Iranian military targets in the days ahead cannot be ruled out.

The latter interventions would be seen as necessary by the US to keep the Middle Eastern military balance in favour of Israel. Consequently, any US-initiated peace moves in the real sense of the phrase in the Middle East would need to be ruled out in the foreseeable future. In other words, Middle East peace will remain elusive.

Interestingly, the leadership moves the Trump administration is hoping to make in Venezuela, post-Maduro, reflect glaringly on its foreign policy preoccupations. Apparently, Trump will be preferring to ‘work with’ Delcy Rodriguez, acting President of Venezuela, rather than Maria Corina Machado, the principal opponent of Nicolas Maduro, who helped sustain the opposition to Maduro in the lead-up to the latter’s ouster and clearly the democratic candidate for the position of Venezuelan President.

The latter development could be considered a downgrading of the democratic process and a virtual ‘slap in its face’. While the democratic rights of the Venezuelan people will go disregarded by the US, a comparative ‘strong woman’ will receive the Trump administration’s blessings. She will perhaps be groomed by Trump to protect the US’s security and economic interests in South America, while his administration side-steps the promotion of the democratic empowerment of Venezuelans.

Features

Silk City: A blueprint for municipal-led economic transformation in Sri Lanka

Maharagama today stands at a crossroads. With the emergence of new political leadership, growing public expectations, and the convergence of professional goodwill, the Maharagama Municipal Council (MMC) has been presented with a rare opportunity to redefine the city’s future. At the heart of this moment lies the Silk City (Seda Nagaraya) Initiative (SNI)—a bold yet pragmatic development blueprint designed to transform Maharagama into a modern, vibrant, and economically dynamic urban hub.

This is not merely another urban development proposal. Silk City is a strategic springboard—a comprehensive economic and cultural vision that seeks to reposition Maharagama as Sri Lanka’s foremost textile-driven commercial city, while enhancing livability, employment, and urban dignity for its residents. The Silk City concept represents more than a development plan: it is a comprehensive economic blueprint designed to redefine Maharagama as Sri Lanka’s foremost textile-driven commercial and cultural hub.

A Vision Rooted in Reality

What makes the Silk City Initiative stand apart is its grounding in economic realism. Carefully designed around the geographical, commercial, and social realities of Maharagama, the concept builds on the city’s long-established strengths—particularly its dominance as a textile and retail centre—while addressing modern urban challenges.

The timing could not be more critical. With Mayor Saman Samarakoon assuming leadership at a moment of heightened political goodwill and public anticipation, MMC is uniquely positioned to embark on a transformation of unprecedented scale. Leadership, legitimacy, and opportunity have aligned—a combination that cities rarely experience.

A Voluntary Gift of National Value

In an exceptional and commendable development, the Maharagama Municipal Council has received—entirely free of charge—a comprehensive development proposal titled “Silk City – Seda Nagaraya.” Authored by Deshamanya, Deshashkthi J. M. C. Jayasekera, a distinguished Chartered Accountant and Chairman of the JMC Management Institute, the proposal reflects meticulous research, professional depth, and long-term strategic thinking.

It must be added here that this silk city project has received the political blessings of the Parliamentarians who represented the Maharagama electorate. They are none other than Sunil Kumara Gamage, Minister of Sports and Youth Affairs, Sunil Watagala, Deputy Minister of Public Security and Devananda Suraweera, Member of Parliament.

The blueprint outlines ten integrated sectoral projects, including : A modern city vision, Tourism and cultural city development, Clean and green city initiatives, Religious and ethical city concepts, Garden city aesthetics, Public safety and beautification, Textile and creative industries as the economic core

Together, these elements form a five-year transformation agenda, capable of elevating Maharagama into a model municipal economy and a 24-hour urban hub within the Colombo Metropolitan Region

Why Maharagama, Why Now?

Maharagama’s transformation is not an abstract ambition—it is a logical evolution. Strategically located and commercially vibrant, the city already attracts thousands of shoppers daily. With structured investment, branding, and infrastructure support, Maharagama can evolve into a sleepless commercial destination, a cultural and tourism node, and a magnet for both local and international consumers.

Such a transformation aligns seamlessly with modern urban development models promoted by international development agencies—models that prioritise productivity, employment creation, poverty reduction, and improved quality of life.

Rationale for Transformation

Maharagama has long held a strategic advantage as one of Sri Lanka’s textile and retail centers. With proper planning and investment, this identity can be leveraged to convert the city into a branded urban destination, a sleepless commercial hub, a tourism and cultural attraction, and a vibrant economic engine within the Colombo Metropolitan Region. Such transformation is consistent with modern city development models promoted by international funding agencies that seek to raise local productivity, employment, quality of life, alleviation of urban poverty, attraction and retaining a huge customer base both local and international to the city)

Current Opportunity

The convergence of the following factors make this moment and climate especially critical. Among them the new political leadership with strong public support, availability of a professionally developed concept paper, growing public demand for modernisation, interest among public, private, business community and civil society leaders to contribute, possibility of leveraging traditional strengths (textile industry and commercial vibrancy are notable strengths.

The Silk City initiative therefore represents a timely and strategic window for Maharagama to secure national attention, donor interest and investor confidence.

A Window That Must Not Be Missed

Several factors make this moment decisive: Strong new political leadership with public mandate, Availability of a professionally developed concept, Rising citizen demand for modernization, Willingness of professionals, businesses, and civil society to contribute. The city’s established textile and commercial base

Taken together, these conditions create a strategic window to attract national attention, donor interest, and investor confidence.

But windows close.

Hard Truths: Challenges That Must Be Addressed

Ambition alone will not deliver transformation. The Silk City Initiative demands honest recognition of institutional constraints. MMC currently faces: Limited technical and project management capacity, rigid public-sector regulatory frameworks that slow procurement and partnerships, severe financial limitations, with internal revenues insufficient even for routine operations, the absence of a fully formalised, high-caliber Steering Committee.

Moreover, this is a mega urban project, requiring feasibility studies, impact assessments, bankable proposals, international partnerships, and sustained political and community backing.

A Strategic Roadmap for Leadership

For Mayor Saman Samarakoon, this represents a once-in-a-generation leadership moment. Key strategic actions are essential: 1.Immediate establishment of a credible Steering Committee, drawing expertise from government, private sector, academia, and civil society. 2. Creation of a dedicated Project Management Unit (PMU) with professional specialists. 3. Aggressive mobilisation of external funding, including central government support, international donors, bilateral partners, development banks, and corporate CSR initiatives. 4. Strategic political engagement to secure legitimacy and national backing. 5. Quick-win projects to build public confidence and momentum. 6. A structured communications strategy to brand and promote Silk City nationally and internationally. Firm positioning of textiles and creative industries as the heart of Maharagama’s economic identity

If successfully implemented, Silk City will not only redefine Maharagama’s future but also ensure that the names of those who led this transformation are etched permanently in the civic history of the city.

Voluntary Gift of National Value

Maharagama is intrinsically intertwined with the textile industry. Small scale and domestic textile industry play a pivotal role. Textile industry generates a couple of billion of rupees to the Maharagama City per annum. It is the one and only city that has a sleepless night and this textile hub provides ready-made garments to the entire country. Prices are comparatively cheaper. If this textile industry can be vertically and horizontally developed, a substantial income can be generated thus providing employment to vulnerable segments of employees who are mostly women. Paucity of textile technology and capital investment impede the growth of the industry. If Maharagama can collaborate with the Bombay of India textile industry, there would be an unbelievable transition. How Sri Lanka could pursue this goal. A blueprint for the development of the textile industry for the Maharagama City will be dealt with in a separate article due to time space.

It is achievable if the right structures, leadership commitments and partnerships are put in place without delay.

No municipal council in recent memory has been presented with such a pragmatic, forward-thinking and well-timed proposal. Likewise, few Mayors will ever be positioned as you are today — with the ability to initiate a transformation that will redefine the future of Maharagama for generations. It will not be a difficult task for Saman Samarakoon, Mayor of the MMC to accomplish the onerous tasks contained in the projects, with the acumen and experience he gained from his illustrious as a Commander of the SL Navy with the support of the councilors, Municipal staff and the members of the Parliamentarians and the committed team of the Silk-City Project.

Voluntary Gift of National Value

Maharagama is intrinsically intertwined with the textile industry. The textile industries play a pivotal role. This textile hub provides ready-made garments to the entire country. Prices are comparatively cheaper. If this textile industry can be vertically and horizontally developed, a substantial income can be generated thus providing employment to vulnerable segments of employees who are mostly women.

Paucity of textile technology and capital investment impede the growth of the industry. If Maharagama can collaborate with the Bombay of India textile industry, there would be an unbelievable transition. A blueprint for the development of the textile industry for the Maharagama City will be dealt with in a separate article.

J.A.A.S Ranasinghe

Productivity Specialist and Management Consultant

(The writer can becontacted via Email:rathula49@gmail.com)

Features

Reading our unfinished economic story through Bandula Gunawardena’s ‘IMF Prakeerna Visadum’

Book Review

Why Sri Lanka’s Return to the IMF Demands Deeper Reflection

By mid-2022, the term “economic crisis” ceased to be an abstract concept for most Sri Lankans. It was no longer confined to academic papers, policy briefings, or statistical tables. Instead, it became a lived and deeply personal experience. Fuel queues stretched for kilometres under the burning sun. Cooking gas vanished from household shelves. Essential medicines became difficult—sometimes impossible—to find. Food prices rose relentlessly, pushing basic nutrition beyond the reach of many families, while real incomes steadily eroded.

What had long existed as graphs, ratios, and warning signals in economic reports suddenly entered daily life with unforgiving force. The crisis was no longer something discussed on television panels or debated in Parliament; it was something felt at the kitchen table, at the bus stop, and in hospital corridors.

Amid this social and economic turmoil came another announcement—less dramatic in appearance, but far more consequential in its implications. Sri Lanka would once again seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The announcement immediately divided public opinion. For some, the IMF represented an unavoidable lifeline—a last resort to stabilise a collapsing economy. For others, it symbolised a loss of economic sovereignty and a painful surrender to external control. Emotions ran high. Debates became polarised. Public discourse quickly hardened into slogans, accusations, and ideological posturing.

Yet beneath the noise, anger, and fear lay a more fundamental question—one that demanded calm reflection rather than emotional reaction:

Why did Sri Lanka have to return to the IMF at all?

This question does not lend itself to simple or comforting answers. It cannot be explained by a single policy mistake, a single government, or a single external shock. Instead, it requires an honest examination of decades of economic decision-making, institutional weaknesses, policy inconsistency, and political avoidance. It requires looking beyond the immediate crisis and asking how Sri Lanka repeatedly reached a point where IMF assistance became the only viable option.

Few recent works attempt this difficult task as seriously and thoughtfully as Dr. Bandula Gunawardena’s IMF Prakeerna Visadum. Rather than offering slogans or seeking easy culprits, the book situates Sri Lanka’s IMF engagement within a broader historical and structural narrative. In doing so, it shifts the debate away from blame and toward understanding—a necessary first step if the country is to ensure that this crisis does not become yet another chapter in a familiar and painful cycle.

Returning to the IMF: Accident or Inevitability?

The central argument of IMF Prakeerna Visadum is at once simple and deeply unsettling. It challenges a comforting narrative that has gained popularity in times of crisis and replaces it with a far more demanding truth:

Sri Lanka’s economic crisis was not created by the IMF.

IMF intervention became inevitable because Sri Lanka avoided structural reform for far too long.

This framing fundamentally alters the terms of the national debate. It shifts attention away from external blame and towards internal responsibility. Instead of asking whether the IMF is good or bad, Dr. Gunawardena asks a more difficult and more important question: what kind of economy repeatedly drives itself to a point where IMF assistance becomes unavoidable?

The book refuses the two easy positions that dominate public discussion. It neither defends the IMF uncritically as a benevolent saviour nor demonises it as the architect of Sri Lanka’s suffering. Instead, IMF intervention is placed within a broader historical and structural context—one shaped primarily by domestic policy choices, institutional weaknesses, and political avoidance.

Public discourse often portrays IMF programmes as the starting point of economic hardship. Dr. Gunawardena corrects this misconception by restoring the correct chronology—an essential step for any honest assessment of the crisis.

The IMF did not arrive at the beginning of Sri Lanka’s collapse.

It arrived after the collapse had already begun.

By the time negotiations commenced, Sri Lanka had exhausted its foreign exchange reserves, lost access to international capital markets, officially defaulted on its external debt, and entered a phase of runaway inflation and acute shortages.

Fuel queues, shortages of essential medicines, and scarcities of basic food items were not the product of IMF conditionality. They were the direct outcome of prolonged foreign-exchange depletion combined with years of policy mismanagement. Import restrictions were imposed not because the IMF demanded them, but because the country simply could not pay its bills.

From this perspective, the IMF programme did not introduce austerity into a functioning economy. It formalised an adjustment that had already become unavoidable. The economy was already contracting, consumption was already constrained, and living standards were already falling. The IMF framework sought to impose order, sequencing, and credibility on a collapse that was already under way.

Seen through this lens, the return to the IMF was not a freely chosen policy option, but the end result of years of postponed decisions and missed opportunities.

A Long IMF Relationship, Short National Memory

Sri Lanka’s engagement with the IMF is neither new nor exceptional. For decades, governments of all political persuasions have turned to the Fund whenever balance-of-payments pressures became acute. Each engagement was presented as a temporary rescue—an extraordinary response to an unusual storm.

Yet, as Dr. Gunawardena meticulously documents, the storms were not unusual. What was striking was not the frequency of crises, but the remarkable consistency of their underlying causes.

Fiscal indiscipline persisted even during periods of growth. Government revenue remained structurally weak. Public debt expanded rapidly, often financing recurrent expenditure rather than productive investment. Meanwhile, the external sector failed to generate sufficient foreign exchange to sustain a consumption-led growth model.

IMF programmes brought temporary stability. Inflation eased. Reserves stabilised. Growth resumed. But once external pressure diminished, reform momentum faded. Political priorities shifted. Structural weaknesses quietly re-emerged.

This recurring pattern—crisis, adjustment, partial compliance, and relapse—became a defining feature of Sri Lanka’s economic management. The most recent crisis differed only in scale. This time, there was no room left to postpone adjustment.

Fiscal Fragility: The Core of the Crisis

A central focus of IMF Prakeerna Visadum is Sri Lanka’s chronically weak fiscal structure. Despite relatively strong social indicators and a capable administrative state, government revenue as a share of GDP remained exceptionally low.

Frequent tax changes, politically motivated exemptions, and weak enforcement steadily eroded the tax base. Instead of building a stable revenue system, governments relied increasingly on borrowing—both domestic and external.

Much of this borrowing financed subsidies, transfers, and public sector wages rather than productivity-enhancing investment. Over time, debt servicing crowded out development spending, shrinking fiscal space.

Fiscal reform failed not because it was technically impossible, Dr. Gunawardena argues, but because it was politically inconvenient. The costs were immediate and visible; the benefits long-term and diffuse. The eventual debt default was therefore not a surprise, but a delayed consequence.

The External Sector Trap

Sri Lanka’s narrow export base—apparel, tea, tourism, and remittances—generated foreign exchange but masked deeper weaknesses. Export diversification stagnated. Industrial upgrading lagged. Integration into global value chains remained limited.

Meanwhile, import-intensive consumption expanded. When external shocks arrived—global crises, pandemics, commodity price spikes—the economy had little resilience.

Exchange-rate flexibility alone cannot generate exports. Trade liberalisation without an industrial strategy redistributes pain rather than creates growth.

Monetary Policy and the Cost of Lost Credibility

Prolonged monetary accommodation, often driven by political pressure, fuelled inflation, depleted reserves, and eroded confidence. Once credibility was lost, restoring it required painful adjustment.

Macroeconomic credibility, Dr. Gunawardena reminds us, is a national asset. Once squandered, it is extraordinarily expensive to rebuild.

IMF Conditionality: Stabilisation Without Development?

IMF programmes stabilise economies, but they do not automatically deliver inclusive growth. In Sri Lanka, adjustment raised living costs and reduced real incomes. Social safety nets expanded, but gaps persisted.

This raises a critical question: can stabilisation succeed politically if it fails socially?

Political Economy: The Missing Middle

Reforms collided repeatedly with electoral incentives and patronage networks. IMF programmes exposed contradictions but could not resolve them. Without domestic ownership, reform risks becoming compliance rather than transformation.

Beyond Blame: A Diagnostic Moment

The book’s greatest strength lies in its refusal to engage in blame politics. IMF intervention is treated as a diagnostic signal, not a cause—a warning light illuminating unresolved structural failures.

The real challenge is not exiting an IMF programme, but exiting the cycle that makes IMF programmes inevitable.

A Strong Public Appeal: Why This Book Must Be Read

This is not an anti-IMF book.

It is not a pro-IMF book.

It is a pro-Sri Lanka book.

Published by Sarasaviya Publishers, IMF Prakeerna Visadum equips readers not with anger, but with clarity—offering history, evidence, and honest reflection when the country needs them most.

Conclusion: Will We Learn This Time?

The IMF can stabilise an economy.

It cannot build institutions.

It cannot create competitiveness.

It cannot deliver inclusive development.

Those responsibilities remain domestic.

The question before Sri Lanka is simple but profound:

Will we repeat the cycle, or finally learn the lesson?

The answer does not lie in Washington.

It lies with us.

By Professor Ranjith Bandara

Emeritus Professor, University of Colombo

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News4 days ago

News4 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNew policy framework for stock market deposits seen as a boon for companies

-

Opinion6 days ago

Opinion6 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II

-

News4 days ago

News4 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament