Opinion

Our rice crisis: A holistic solution – II

by Emeritus Professor Ranjith Senaratne

Department of Crop Science, University of Ruhuna (ransen.ru@gmail.com)

(Continued from 03 March, 2025)

Voiceless farmers and toothless farmer organisations

The hapless farmers, who render a yeoman service to the nation by ensuring food and nutritional security are often at the mercy of some large-scale rice traders and millers. They get a raw deal at the end of the day, and this vicious cycle has gone on for many years with no end in sight. Consequently, every year, several “nation’s feeders” take their own lives out of sheer frustration and hopelessness. There are farmers’ organisations in the country who speak on behalf of the hapless farmer, but their protests seldom make an impact on the politicians and policy makers to change the status quo. What is most ironic is that the millions of paddy farmers who feed the nation are voiceless and powerless, while even private bus drivers, three-wheeler drivers and railway guards, to name a few, are much more powerful and make themselves heard.

However, many countries have powerful farmer organisations that wield much influence at the national level. Hence, it is possible and important to strengthen and give muscle to local farmer organisations through awareness, professional training and capacity building so that they could evolve into a vibrant and powerful force that cannot be brushed aside, but must be reckoned with by the policy makers, planners and politicians. Opportunistic political elements with ulterior motives masquerading as farmer representatives should not be allowed to exploit these hapless “nation feeders” for their narrow political ends, something which is unfortunately evident in our country. The Faculties of Agriculture and professional bodies in allied fields have a responsibility and moral obligation to provide leadership and guidance to bona fide farmer organisations which will contribute not only to improving the socio-economic standard of the millions of farmers and their families, but also to enhancing food and nutritional security in the country.

Uncoordinated and unregulated crop production

There is a plethora of government institutions in the agricultural sector, yet no institution is mandated to coordinate and regulate the national crop production. Taking into account land capability, climatic potential, food demand, export potential etc. will minimise food surpluses and scarcities and overuse of fertilisers and pesticides while ensuring a fair price to both the farmer and consumer. Presently, anybody with land and the necessary resources and inputs can cultivate any crop anywhere on any scale at any time. However, in many countries, food production and food imports are carefully regulated to minimise food surplus and scarcity. Farmers are given incentives to produce less when a glut is anticipated and to produce more when a scarcity is likely. Such decisions are based on market surveys, meteorological forecasts and past experience, ensuring fairly stable prices throughout the year.

In each district, govt. support such as fertiliser subsidies, crop insurance, provision of water, bank loans, etc., should be provided only to farmers with a proven track record who cultivate paddy in productive areas adhering to the recommended cultural practices. If a field with high potential produces a low yield, it is likely to be associated with poor management. Cultivation of such paddy fields should be given to promising farmers in the area and benefits should be shared between the two parties in an equitable manner. This will help realise the potential yield from the field. Such intervention could be made with the support of the farmer organisations in the area.

Lack of robust anti-hoarding laws

Hoarding of agricultural produce and the consequences arising therefrom have posed formidable challenges to governments and caused untold hardships to the consumers in many parts of the world. As regard paddy production in Sri Lanka, it is reported that nearly 70% is purchased by the small and medium scale millers and the remaining 30% by a few large scale millers. While the veracity of those figures is yet to be established, the existing laws and regulations are not robust enough to effectively deal with the issues of hoarding and associated problems which have precipitated a prolonged crisis in the country. In this context, it is appropriate to see how the Philippines has dealt with a similar problem. The new law, Anti-Agricultural Economic Sabotage Act, enacted by the Dept. of Agriculture in the Philippines in September, 2024 has declared smuggling and hoarding of agricultural products as economic sabotage and has imposed stiff penalties against smugglers and hoarders of agricultural food products, including heavy fines, i.e. 5 times the value of smuggled and hoarded agricultural products and life imprisonment if found guilty. Such deterrent punishment would benefit the farmers and fisher folk whose livelihoods have been jeopardized by unscrupulous traders and smugglers (https://www.da.gov.ph/da-chief-new-law-declares-smuggling-hoarding-of-agricultural-products-as-economic-sabotage/). The Government in our country could introduce such laws to deal with undisclosed hoarding of agricultural produce and products by traders and millers. Through constructive engagement with traders and millers and deployment of electronic sensor based computational intelligence in storage bins or silos, the govt. will be able to ascertain the stock position on a real-time basis so that necessary interventions could be made to minimize shortages and price fluctuations in rice. This technology has many applications in smart inventory and stock management and such technological interventions can be facilitated by the newly established Ministry of Digital Technology.

In order to avoid making this article lengthy, I have not elaborated on some further factors contributing to the rice crisis. However, they have been dealt with in the book edited by the writer in 2021 titled “The Future of the Agriculture and the Agriculture of the Future: From Beaten Track to Untrodden Paths”.

Conclusions

Availability of rice and its price depend on the rice value chain which encompasses not only a multitude of actors and players, but also several sectors of the economy. Therefore, there are no simple, straight forward solutions to such a complex, multi-faceted and multi-dimensional problem, and tinkering with the system is to no avail and will only aggravate matters. This problem, developed over many years, demands a holistic systems approach through transsdisciplinary interventions. Here, the issue should be viewed in an integrated manner as a collection of interconnected and interdependent elements and people, taking into account the relationships and interactions between them. This calls for a paradigm shift and bold, proactive and pragmatic moves in order to bring about a sustainable solution to this complex, intractable and drawn-out problem, thereby ensuring year-round availability of rice at an affordable price to the ordinary citizen.

This would, among other things, include enactment of the requisite laws and regulations to deal with the oligopoly of rice trade and the lack of price regulation of key imported agricultural inputs such as pesticides, weedicides, fungicides etc. and services such as hiring of machinery for land preparation, harvesting, threshing etc. for which the farmers presently pay exorbitant prices. In addition, announcing the guaranteed price of paddy only after the harvest is an unkind cut. The price should be made known to the prospective farmers well ahead of the beginning of the cultivation season, thereby giving them an opportunity and the space to decide whether to cultivate paddy on a commercial scale and, if so, to what extent.

Needless to add that the hapless farmers are at the mercy of the large-scale rice millers and traders, including input and service providers. However, we must recognize the pivotal and crucial role they play in supporting the paddy production and providing quality rice to the consumer. However, the failures of the governments to date to enact and enforce the requisite laws and regulations have made the farmers extremely vulnerable and prone to exploitation in a fiercely competitive globalized environment where ethical and moral values are fast eroding.

Therefore what is needed in this decisive hour in not to continue finding fault with and flogging the large-scale millers and traders, or blaming the previous regimes, but to make proactive and constructive moves, hasten to enact pragmatic and actionable laws and regulations, and beef up the relevant law enforcement and regulatory authorities such as Consumer Affairs Authority, providing them with the much needed teeth and resources to address the said key issues as a matter of top priority and the utmost urgency. The government has received an overwhelming mandate with 159 members in the parliament. Hence, the above interventions will be only a walk in the park for the government to introduce. The earlier it happens, the better, since the next rice crisis, like the second wave of the tsunami in 2004, could be much worse and more disastrous not only in economic and social, but also in political terms.

(The writer appreciates the comments and observations made by Dr. W.M.W. Weerakoon, former Director General, Dept. of Agriculture, Dr. Sumith Abeysiriwardena, former Director, Rice Research and Development Institute, Bathalagoda and Mr. C.S. Kumarasinghe, Senior Lecturer, Department of Crop Science, University of Ruhuna on a draft of this article)

Opinion

Buddhist insights into the extended mind thesis – Some observations

It is both an honour and a pleasure to address you on this occasion as we gather to celebrate International Philosophy Day. Established by UNESCO and supported by the United Nations, this day serves as a global reminder that philosophy is not merely an academic discipline confined to universities or scholarly journals. It is, rather, a critical human practice—one that enables societies to reflect upon themselves, to question inherited assumptions, and to navigate periods of intellectual, technological, and moral transformation.

In moments of rapid change, philosophy performs a particularly vital role. It slows us down. It invites us to ask not only how things work, but what they mean, why they matter, and how we ought to live. I therefore wish to begin by expressing my appreciation to UNESCO, the United Nations, and the organisers of this year’s programme for sustaining this tradition and for selecting a theme that invites sustained reflection on mind, consciousness, and human agency.

We inhabit a world increasingly shaped by artificial intelligence, neuroscience, cognitive science, and digital technologies. These developments are not neutral. They reshape how we think, how we communicate, how we remember, and even how we imagine ourselves. As machines simulate cognitive functions once thought uniquely human, we are compelled to ask foundational philosophical questions anew:

What is the mind? Where does thinking occur? Is cognition something enclosed within the brain, or does it arise through our bodily engagement with the world? And what does it mean to be an ethical and responsible agent in a technologically extended environment?

Sri Lanka’s Philosophical Inheritance

On a day such as this, it is especially appropriate to recall that Sri Lanka possesses a long and distinguished tradition of philosophical reflection. From early Buddhist scholasticism to modern comparative philosophy, Sri Lankan thinkers have consistently engaged questions concerning knowledge, consciousness, suffering, agency, and liberation.

Within this modern intellectual history, the University of Peradeniya occupies a unique place. It has served as a centre where Buddhist philosophy, Western thought, psychology, and logic have met in creative dialogue. Scholars such as T. R. V. Murti, K. N. Jayatilleke, Padmasiri de Silva, R. D. Gunaratne, and Sarathchandra did not merely interpret Buddhist texts; they brought them into conversation with global philosophy, thereby enriching both traditions.

It is within this intellectual lineage—and with deep respect for it—that I offer the reflections that follow.

Setting the Philosophical Problem

My topic today is “Embodied Cognition and Viññāṇasota: Buddhist Insights on the Extended Mind Thesis – Some Observations.” This is not a purely historical inquiry. It is an attempt to bring Buddhist philosophy into dialogue with some of the most pressing debates in contemporary philosophy of mind and cognitive science.

At the centre of these debates lies a deceptively simple question: Where is the mind?

For much of modern philosophy, the dominant answer was clear: the mind resides inside the head. Thinking was understood as an internal process, private and hidden, occurring within the boundaries of the skull. The body was often treated as a mere vessel, and the world as an external stage upon which cognition operated.

However, this picture has increasingly come under pressure.

The Extended Mind Thesis and the 4E Turn

One of the most influential challenges to this internalist model is the Extended Mind Thesis, proposed by Andy Clark and David Chalmers. Their argument is provocative but deceptively simple: if an external tool performs the same functional role as a cognitive process inside the brain, then it should be considered part of the mind itself.

From this insight emerges the now well-known 4E framework, according to which cognition is:

Embodied – shaped by the structure and capacities of the body

Embedded – situated within physical, social, and cultural environments

Enactive – constituted through action and interaction

Extended – distributed across tools, artefacts, and practices

This framework invites us to rethink the mind not as a thing, but as an activity—something we do, rather than something we have.

Earlier Western Challenges to Internalism

It is important to note that this critique of the “mind in the head” model did not begin with cognitive science. It has deep philosophical roots.

Ludwig Wittgenstein

famously warned philosophers against imagining thought as something occurring in a hidden inner space. Such metaphors, he suggested, mystify rather than clarify our understanding of mind.

Similarly, Franz Brentano’s notion of intentionality—his claim that all mental states are about something—shifted attention away from inner substances toward relational processes. This insight shaped Husserl’s phenomenology, where consciousness is always world-directed, and Freud’s psychoanalysis, where mental life is dynamic, conflicted, and socially embedded.

Together, these thinkers prepared the conceptual ground for a more process-oriented, relational understanding of mind.

Varela and the Enactive Turn

A decisive moment in this shift came with Francisco J. Varela, whose work on enactivism challenged computational models of mind. For Varela, cognition is not the passive representation of a pre-given world, but the active bringing forth of meaning through embodied engagement.

Cognition, on this view, arises from the dynamic coupling of organism and environment. Importantly, Varela explicitly acknowledged his intellectual debt to Buddhist philosophy, particularly its insights into impermanence, non-self, and dependent origination.

Buddhist Philosophy and the Minding Process

Buddhist thought offers a remarkably sophisticated account of mind—one that is non-substantialist, relational, and processual. Across its diverse traditions, we find a consistent emphasis on mind as dependently arisen, embodied through the six sense bases, and shaped by intention and contact.

Crucially, Buddhism does not speak of a static “mind-entity”. Instead, it employs metaphors of streams, flows, and continuities, suggesting a dynamic process unfolding in relation to conditions.

Key Buddhist Concepts for Contemporary Dialogue

Let me now highlight several Buddhist concepts that are particularly relevant to contemporary discussions of embodied and extended cognition.

The notion of prapañca, as elaborated by Bhikkhu Ñāṇananda, captures the mind’s tendency toward conceptual proliferation. Through naming, interpretation, and narrative construction, the mind extends itself, creating entire experiential worlds. This is not merely a linguistic process; it is an existential one.

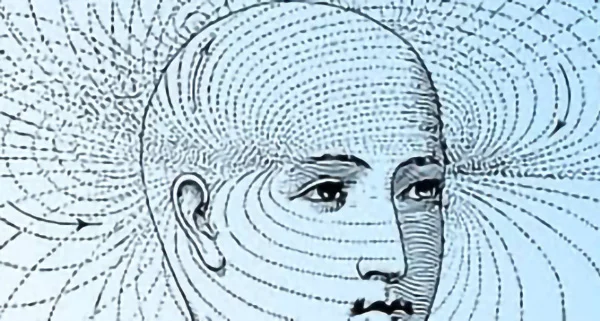

The Abhidhamma concept of viññāṇasota, the stream of consciousness, rejects the idea of an inner mental core. Consciousness arises and ceases moment by moment, dependent on conditions—much like a river that has no fixed identity apart from its flow.

The Yogācāra doctrine of ālayaviññāṇa adds a further dimension, recognising deep-seated dispositions, habits, and affective tendencies accumulated through experience. This anticipates modern discussions of implicit cognition, embodied memory, and learned behaviour.

Finally, the Buddhist distinction between mindful and unmindful cognition reveals a layered model of mental life—one that resonates strongly with contemporary dual-process theories.

A Buddhist Cognitive Ecology

Taken together, these insights point toward a Buddhist cognitive ecology in which mind is not an inner object but a relational activity unfolding across body, world, history, and practice.

As the Buddha famously observed, “In this fathom-long body, with its perceptions and thoughts, I declare there is the world.” This is perhaps one of the earliest and most profound articulations of an embodied, enacted, and extended conception of mind.

Conclusion

The Extended Mind Thesis challenges the idea that the mind is confined within the skull. Buddhist philosophy goes further. It invites us to reconsider whether the mind was ever “inside” to begin with.

In an age shaped by artificial intelligence, cognitive technologies, and digital environments, this question is not merely theoretical. It is ethically urgent. How we understand mind shapes how we design technologies, structure societies, and conceive human responsibility.

Buddhist philosophy offers not only conceptual clarity but also ethical guidance—reminding us that cognition is inseparable from suffering, intention, and liberation.

Dr. Charitha Herath is a former Member of Parliament of Sri Lanka (2020–2024) and an academic philosopher. Prior to entering Parliament, he served as Professor (Chair) of Philosophy at the University of Peradeniya. He was Chairman of the Committee on Public Enterprises (COPE) from 2020 to 2022, playing a key role in parliamentary oversight of public finance and state institutions. Dr. Herath previously served as Secretary to the Ministry of Mass Media and Information (2013–2015) and is the Founder and Chair of Nexus Research Group, a platform for interdisciplinary research, policy dialogue, and public intellectual engagement.

He holds a BA from the University of Peradeniya (Sri Lanka), MA degrees from Sichuan University (China) and Ohio University (USA), and a PhD from the University of Kelaniya (Sri Lanka).

(This article has been adapted from the keynote address delivered

by Dr. Charitha Herath

at the International Philosophy Day Conference at the University of Peradeniya.)

Opinion

We do not want to be press-ganged

Reference ,the Indian High Commissioner’s recent comments ( The Island, 9th Jan. ) on strong India-Sri Lanka relationship and the assistance granted on recovering from the financial collapse of Sri Lanka and yet again for cyclone recovery., Sri Lankans should express their thanks to India for standing up as a friendly neighbour.

On the Defence Cooperation agreement, the Indian High Commissioner’s assertion was that there was nothing beyond that which had been included in the text. But, dear High Commissioner, we Sri Lankans have burnt our fingers when we signed agreements with the European nations who invaded our country; they took our leaders around the Mulberry bush and made our nation pay a very high price by controlling our destiny for hundreds of years. When the Opposition parties in the Parliament requested the Sri Lankan government to reveal the contents of the Defence agreements signed with India as per the prevalent common practice, the government’s strange response was that India did not want them disclosed.

Even the terms of the one-sided infamous Indo-Sri Lanka agreement, signed in 1987, were disclosed to the public.

Mr. High Commissioner, we are not satisfied with your reply as we are weak, economically, and unable to clearly understand your “India’s Neighbourhood First and Mahasagar policies” . We need the details of the defence agreements signed with our government, early.

RANJITH SOYSA

Opinion

When will we learn?

At every election—general or presidential—we do not truly vote, we simply outvote. We push out the incumbent and bring in another, whether recycled from the past or presented as “fresh.” The last time, we chose a newcomer who had spent years criticising others, conveniently ignoring the centuries of damage they inflicted during successive governments. Only now do we realise that governing is far more difficult than criticising.

There is a saying: “Even with elephants, you cannot bring back the wisdom that has passed.” But are we learning? Among our legislators, there have been individuals accused of murder, fraud, and countless illegal acts. True, the courts did not punish them—but are we so blind as to remain naive in the face of such allegations? These fraudsters and criminals, and any sane citizen living in this decade, cannot deny those realities.

Meanwhile, many of our compatriots abroad, living comfortably with their families, ignore these past crimes with blind devotion and campaign for different parties. For most of us, the wish during an election is not the welfare of the country, but simply to send our personal favourite to the council. The clearest example was the election of a teledrama actress—someone who did not even understand the Constitution—over experienced and honest politicians.

It is time to stop this bogus hero worship. Vote not for personalities, but for the country. Vote for integrity, for competence, and for the future we deserve.

Deshapriya Rajapaksha

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoDialog and UnionPay International Join Forces to Elevate Sri Lanka’s Digital Payment Landscape

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoSajith: Ashoka Chakra replaces Dharmachakra in Buddhism textbook

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoThe Paradox of Trump Power: Contested Authoritarian at Home, Uncontested Bully Abroad

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoSubject:Whatever happened to (my) three million dollars?

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoLevel I landslide early warnings issued to the Districts of Badulla, Kandy, Matale and Nuwara-Eliya extended

-

News3 days ago

News3 days ago65 withdrawn cases re-filed by Govt, PM tells Parliament

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoNational Communication Programme for Child Health Promotion (SBCC) has been launched. – PM

-

Opinion5 days ago

Opinion5 days agoThe minstrel monk and Rafiki, the old mandrill in The Lion King – II