Opinion

Orani Jansz – live wire of university English teaching programme

APPRECIATION

I am saddened to hear of the passing away of Orani Jansz, who became one of the dynamic coordinators of the English teaching programme in the universities. This is an opportunity to review the lessons we can learn from that era, as the same problems still exist today. I knew of Orani as a first year chemistry student in 1962 at the Colombo campus, when she was also a batch mate of Raddy Jansz and others in the General Science Qualifying programme. I was responsible for some of their chemistry lectures as well as chemistry practicals.

Orani Jansz was among those who were recruited to the ” English for all undergraduates” programme, launched in 1974, when I became the President of the Vidyodaya campus. I remember very clearly seeing the name of Orani Jansz in the list of applicants, and being agreeably surprised by it. We had diverse people, e.g., science graduates like Orani, and law students like Basil Fernando (now in Hong Kong) applying for teaching positions in the English project. Surprisingly, there were no “English Honours” applicants. Professor Gunawardena, the Head of the English Department was the enthusiastic live wire of the programme.

The “English for all undergraduates” was part of a curriculum overhaul (together with the introduction of course units etc.) that I began as soon as I became campus president. The moment the programme was launched, the “progressive”, “Marxist”, as well as “Nationalist” student leaders, rose against it. At the time S. B. Dissanayake was the leader of the campus Communist party and was the dominant student leader. Dissanayake and Mahinda Wijesekera (student leader of the Science Faculty with JVP links) declared their complete opposition to it. This was said to be “an attack on students using the “Kaduwa”. The “Kaduwa” or “sword” was the nickname for English used by the student leaders who regarded it as a weapon used by the “Kultoor set”. They threatened to reply in kind to the “Kadu Haramba” unless we stopped the programme immediately.

There were also threats to physically attack the English Instructors if they came to the campus to teach English. I rejected their threats and we proceeded to hire instructors, etc., when the student leaders launched a one-day strike as a test of strength. I had also asked Mr. Munasinghe, the Head of the Management Department, to ensure that no instructors were threatened. Mr. Munasinghe was well entrenched in the Gangodawila-Raththanapitya area and he informed the student leaders that any attacks on the instructors will be met by attacks on the student leaders by the village folk at the “Wijayaraama Junction”.

Some of the “moderate” student leaders, e.g., the World University Services (WUS) representative Gajaba, as well as the main student union, presented a “compromise” proposal, namely, that we should teach Russian instead of a “colonial language” like English. Instead of rejecting that as being absurd and inappropriate, I agreed that I can make immediate arrangements for holding Russian classes for those who wished to attend, while English will also continue. This was accepted by the student union. The Russian embassy was willing to provide a teacher, but not immediately.

However, I knew a Russian lady living in Colombo, and she agreed to give a few lessons in the interim. The first lesson attracted a large number of students, no doubt corralled in by the student leaders. So we had to hold the Russian class in the “arts hall” (called the “Lenin Hall” by the student leaders). After the first Russian lesson, there was a faster-than exponential decrease in numbers attending the subsequent classes. After about four classes there was no one turning up, and we terminated the teaching of Russian. Meanwhile the English department did a great job of developing a programme for teaching English to undergraduates who knew only their mother tongue.

It was the dedication of individuals, like Orani Jansz, that made the English Language programme a success. However, my attempts to modify the curriculum was viewed with great suspicion and antipathy by the student leaders, as well as some of the older members of the teaching staff. Their struggle continued for over an year. The option to have a degree named “B. Dev.” to cover what I called “Development Studies”, that looked at curricula in terms of their potential for national development, was treated with great suspicion by the faculties, as many of the staff felt that they may have to “re-learn” new stuff. However, the student leaders were supportive of getting a B. Dev. Instead of a “BA” that was felt to have no “Thathvaya” (Prestige). The Daily News columnist “Viranga” wrote a piece on the obsession of the students on “Thathvaya”, quoting me, and we had to face a day of strikes!

At the time, the students were given a degree on the basis of one giant “final exam”, with no credit for, or taking account of course work. Continuous assessment of the pedagogic process required holding and grading exams periodically, and evaluation of course work All this was considered by the older staff as “extra work” for them. Many lecturers, especially in the Arts faculty, normally tuned up just in time for their lecture and promptly went home, and considered their job to be over. Student leaders who rarely attended lectures feared course evaluation and the possible expelling of students who do not attend lectures or practicals. Their opposition, channelled through the Head of one of the science departments, and using strikes and threats, was supported by Mr. Sumanadasa, the then Vice Chancellor who trembled with fear whenever the student leaders came to his office and dictated terms.

The vacillations and actions of the Vice Chancellor were detrimental to the line of authority in the campus that was needed to carry out necessary reforms. He ignored the transgressions of students at every level, including unacceptable levels of ragging. Staff members who had been assaulted by student leaders lacked backbone and withdrew their complaints under further threats from students. The campus president was to handle all threats without any recourse to the police! The growth of naked violence in the campuses, as well as the waste of public money, seemed to be of no interest to authorities even after the failed 1971 JVP uprising. While the Central Bank refused foreign exchange to buy vital spare parts for lab equipment, “cyclostyle” wax sheets, or books needed for the new programme, it readily approved plastic wrap for cigarette companies. Ananda Meegama, then at the Central Bank approved some money on a personal basis when I saw him about all this. I felt that to be an unacceptable way of getting things done.

Political leaders were cheap enough to even undermine the university. For example, I managed to secure a much needed vehicle from a returning British diplomat; she was willing to just give it to the campus as a gift. Having got wind of it through a student leader, an influential MP claimed the vehicle for himself, because vehicle imports were banned in those days of “foreign exchange control”.

One has to look back to those times and say that individuals like Orani Jansz had to do their bit in an environment where campuses were in the grip of false ideologies. Unfortunately, things seem to have hardly changed today, given the horror stories of current campus raggings.

CHANDRE

DHARMAWARDANA

Opinion

Beyond 4–5% recovery: Why Sri Lanka needs a real growth strategy

The Central Bank Governor’s recent remarks projecting 4–5 percent growth in 2026 and highlighting improving reserves, lower inflation, and financial stability have been widely welcomed. After the trauma of Sri Lanka’s economic crisis, any sign of normalcy is understandably reassuring. Yet, this optimism needs to be read carefully. What is being presented is largely a story of stabilisation and recovery, framed in the familiar IMF language of macroeconomic management. That is necessary, but it is not the same as a pathway to durable growth.

The first issue is the nature of the projected growth itself. A 4–5 percent expansion can occur for many reasons, not all of which strengthen an economy in the long run. In this case, a significant part of the momentum is expected to come from post-cyclone reconstruction and public investment. This will boost activity in construction and related services and create jobs in the short term. But such growth is typically demand-led and temporary. It raises GDP without necessarily expanding the country’s productive capacity, technological capability, or export competitiveness. Once the reconstruction cycle fades, so may the growth.

This points to a crucial distinction that often gets blurred in public debate: economic recovery and durable growth are not the same thing. Recovery means returning to a more normal macro environment—lower inflation, a more stable exchange rate, some rebuilding of reserves, and a functioning financial system. Durable growth, by contrast, requires rising productivity, structural change, and a stronger export base. Sri Lanka can achieve the first without securing the second. Indeed, that is precisely what happened in earlier post-crisis episodes, where short-lived recoveries were followed by renewed external stress.

The Central Governor’s narrative is best understood as an IMF-style stabilisation narrative. Its centre of gravity is macro control: inflation targets, policy rates, reserves, debt service, and financial-sector resilience. These are the right tools for preventing another crisis. But they are not a strategy for accelerating development. IMF programmes are designed primarily to restore confidence, manage risk, and stabilise the macroeconomy. They are not designed to answer the core development questions: What will Sri Lanka produce? What will it export? How will productivity rise? Which sectors will drive long-term growth?

Seen in this light, a projected 4–5 per cent growth rate is best described as moderate recovery growth. It may be entirely plausible—especially if driven by reconstruction and public spending—but it is not the kind of growth that closes income gaps, absorbs underemployment at scale, creates sustained fiscal space, or materially reduces debt burdens. Countries that have successfully caught up in Asia typically sustained 7–8 per cent (or higher) growth for long periods, powered by export expansion, industrial upgrading, and continuous learning.

If the current government’s development agenda is genuinely ambitious, then there is a clear mismatch between the growth implied by that ambition and the growth described in the Central Bank’s outlook. A strategy that settles for 4–5 per cent risks normalising mediocrity rather than mobilising the economy for take-off. Reconstruction-led and consumption-led expansions can lift GDP in the short run, but they do not, by themselves, deliver the productivity and export breakthroughs needed for sustained 7–8 per cent growth.

There is also a risk that reconstruction-driven growth will recreate old external vulnerabilities. Large-scale rebuilding increases demand for cement, steel, fuel, machinery, and transport services—many of which are import-intensive in Sri Lanka. This means higher growth can go hand in hand with a widening trade deficit, renewed pressure on foreign exchange, and imported inflation. The Governor has rightly warned about inflationary and external pressures, but the deeper issue is structural: without a parallel expansion of export capacity and domestic production of tradables, stimulus-driven growth can quickly collide with the same constraints that caused past crises.

The improvement in reserves and the claim that debt service is “manageable” are positive developments. But they should be treated as buffers, not proof of long-term security. Sri Lanka’s recent history shows how quickly reserves can be run down when imports surge, exports disappoint, or global conditions tighten. Reserves buy time. They do not, by themselves, change the underlying growth model.

Similarly, the focus on bringing inflation back towards target and maintaining steady policy rates reflects sound central banking. Price stability and financial-sector resilience are public goods. But an inflation target is not a growth strategy. Durable growth comes from investment in productive capacity, from learning and technological upgrading, from moving into higher-value activities, and from building competitive export sectors. Without these, macro stability becomes an exercise in maintenance rather than transformation.

The repeated reference to “structural reforms” also needs to be treated with care. In policy practice, this often means reforms to pricing, state-owned enterprises, taxation, and public finance management. These may improve efficiency and governance, and they matter. But in development economics, structural transformation means something more demanding: a change in what the country produces, how it produces, and what it sells to the world. It means shifting resources into higher-productivity, more technologically advanced, and more export-oriented activities. Without that shift, an economy can be well-managed and still remain fragile.

What is striking in the Governor’s statement is not that it is wrong, but that it is incomplete. We hear a great deal about stability, recovery, and resilience. We hear much less about the growth strategy itself. Which sectors are expected to lead the next phase of growth beyond construction and consumption? How will exports be diversified and upgraded? What is the plan for skills, technology, and productivity? How will private investment be steered toward tradable, foreign-exchange-earning activities?

These are not academic questions. They go to the heart of whether Sri Lanka is merely staging another rebound or beginning a genuine breakthrough. The country’s repeated crises have shown that returning to “normal” is not enough if the underlying growth model remains unchanged.

In sum, the Central Bank Governor’s optimism should be understood for what it is: a stabilisation narrative, not yet a development strategy. It tells us that the economy is becoming calmer, more predictable, and less crisis-prone—and that is a real and necessary achievement. But it does not yet tell us how Sri Lanka will grow fast enough, long enough, and differently enough to escape its long-standing cycle of weak exports, external vulnerability, and stop–go growth.

A recovery built on reconstruction, consumption, and macro control can deliver 4–5 per cent growth. But the government’s own ambitions—and Sri Lanka’s development needs—require 7–8 per cent sustained growth driven by productivity, exports, and structural transformation. That kind of growth does not emerge automatically from stability. It must be designed, coordinated, and pursued through a clear strategy for production, learning, and upgrading.

Stability is essential. Without it, nothing else is possible. But stability is not a development strategy. It is the foundation on which a strategy must be built. The real test for policymakers now is not whether they can keep the economy stable, but whether they can articulate and implement a credible growth strategy that turns stability into momentum and recovery into transformation. Until that strategy is clearly on the table, Sri Lanka’s current optimism—welcome as it is—should be read with caution, not complacency.

by Prof. Ranjith Bandara

Opinion

V. Shanmuganyagam (1940-2026): First Clas Engineer, First Class Teacher

Quiet flows another don. The aging fraternity of Peradeniya Engineering alumni has lost another one of its beloved teachers. V. Shanmuganayagam, an exceptionally affable and popular lecturer for nearly two decades at the Peradeniya Engineering Faculty, passed away on 15 January 2026, in Markham, Toronto, Canada. Shan, as he was universally known, graduated with First Class Honours in Civil Engineering, in 1962, when the Faculty was located in Colombo. He taught at Peradeniya from 1967 to 1984, and later at the Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, before retiring to live in Canada.

In October last year, one of our colleagues, Engineer P. Balasundram, organized a lunch in Toronto to felicitate Shan. It was very well attended and Shan was in good spirits. At 85 he was looking as young as any of us, except for using a wheelchair to facilitate his movement. The gathering was remarkable for the outpouring of warmth and gratitude by nearly 40 or 50 Engineers, who had graduated in the early 1970s and now in their own seventies. One by one every one who was there spoke and thanked Shan for making a difference in their lives as a teacher and a mentor, not only in their professional lives but by extension in their personal lives as well.

As we were leaving the luncheon gathering there were suggestions to have more such events and to have Shan with us for more reminiscing. That was not to be. Within three months, a sudden turn for the worse in his condition proved to be irreversible. He passed away peacefully, far away across the world from the little corner of little Sri Lanka where he was born and raised, and raised in a manner to make a mark in his life and to make a difference in the lives of others who were his family, friends and several hundreds of engineering professionals whom he taught.

V. Shanmuganayagam was born on May 30, 1940, in Point Pedro, to Culanthavel and Sellam Venayagampillai. His family touchingly noted in the obituary that he was raised in humble beginnings, but more consequentially his values were cast in the finest of moulds. He studied at Hartley College, Point Pedro, and was one of the four outstanding Hartleyites to study engineering, get their first class and join the academia. Shan was preceded by Prof. A. Thurairajah, easily Sri Lanka’s most gifted academic engineering mind, and was followed by David Guanaratnam and A.S. Rajendra. All of them did Civil Engineering, and years later Hartley would send a new pair of outstanding students, M. Sritharan and K. Ramathas who would go on to become highly accomplished Electrical Engineers.

Shan graduated in 1962 with First Class Honours and may have been one of a very few if not the only first class that year. Shan worked for a short while at the Ceylon Electricity Board before proceeding to Cambridge for postgraduate studies specializing in Structures. His dissertation on the Ultimate Strength of Encased Beams is listed in the publications of the Cambridge Structures Group. He returned to his job at CEB and then joined the Faculty in 1967. At that time, Shan may have been one of the more senior lecturers in Structures after Milton Amaratunga who too passed away late last year in Southampton, England.

When we were students in the early 1970s, there was an academic debate at the Faculty as to whether a university or specific faculties should give greater priority to teaching or research. Shan was on the side of teaching and he was quite open about it in his classes. He would supplement his lectures with cyclostyled sheets of notes and the students naturally loved it. It was also a time when Shan and many of his colleagues were young bachelors at Peradeniya, and their lives as academic bachelors have been delightfully recounted in a number of online circulations.

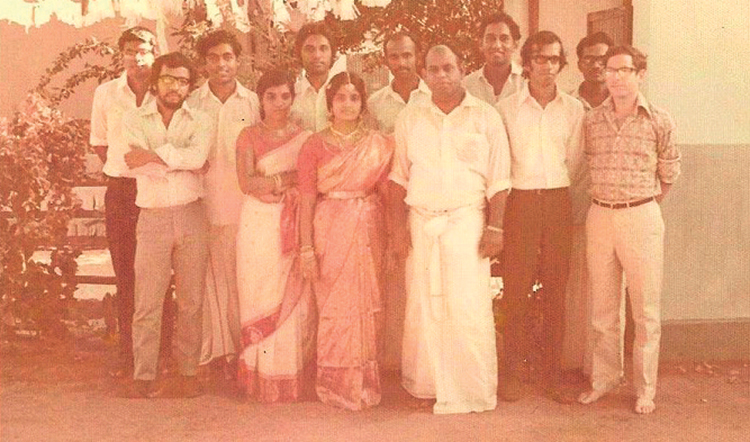

The cross-sectional camaraderie at the Faculty in those days is well captured in one of the photographs taken at Shan’s wedding at Point Pedro, in 1974, which too has been doing the rounds and which I have inserted above. Flanking Shan and his bride Kalamathy, from Left to Right are, M. Dhanendran, Nandana Rambukwella, K. Jeyapalan, Wickrama Bahu Karunaratne, A.S. Rajendra, Lal Tennekoon, Tusit Weerasooria, and R. Srikantha. Sadly, Rambukwella, Karunaratne (Bahu), Tennekoon and now Shan himself, are no longer with us.

Like other faculty members, Shan kept contact with his former students turned practising engineers and they would reach out to him to solicit his expertise in their projects. In the early 1980s, when I was working as Resident Project Manager with my Peradeniya contemporaries, JM Samoon and K. Balasundram, at the Hanthana Housing Scheme undertaken by the National Development Housing Authority (NHDA), Shan was one of the project consultants helping us with concrete technology involving mix design and in situ strength testing using the testing facilities at the Faculty.

The Hanthana Team Looking back, the Hanthana housing scheme construction was the engineering externalization of the architectural imaginings of Tanya Iousova and Suren Wickremesinghe, for building houses on hill slopes without flattening the hills. The project involved the construction of hundreds of housing units with supporting infrastructure comprising roads and drainage, water supply and sanitary, and electricity distribution using underground cables. Tanya & Suren Wickremasinghe were the Architects with an Italian construction company as contractors.

To their credit, Tanya and Suren assembled quite a team of Consulting Engineers that was a cross-section of E’Fac alumni, viz., Siripala Kodikkara and Siripala Jayasinghe (Contract Administration); Prof. Thurairajah (Foundations & Soil Mechanics); S.A. Karunaratne (Structures); V. Shanmuganyagam (Concrete Technology); Neville Kottagama and DLO Mendis (Roads & Drainage); K. Suntharalingam (Water Supply & Sanitary); and Chris Ratnayake (Electrical).

As esoteric gossip goes, DLO Mendis had an informal periodization of engineering graduates, identifying them as either Before-Thurai or After-Thurai, centered on 1957 – the year Prof. Thurairajah graduated with supreme distinction and went on to do groundbreaking theoretical research in Soil Mechanics at Cambridge. Of the Hanthana consultant team, Neville Kottagama and DLO Mendis were before Thurai by six years, Shan was five years after, and all the others came later. Sadly though, only Tanya and Chris are with us today from the 1980s group named above.

After Hanthana came 1983 when all hell broke loose and hundreds of professionals and their families were forced to leave Sri Lanka. Shan left Peradeniya and joined Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, encouraged by his Cambridge contemporaries from Singapore. He taught at Nanyang for twelve years (1984-1996) before moving to Canada with his wife and three sons who were by then ready for university education.

All three children have done exceptionally well in their studies and professional careers. The oldest, Dhanansayan, is a Medical Doctor and a Professor at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, in Madison, United States. That was where India’s Jayaprakash Narayan and Sri Lanka’s Philip Gunawardena had their university education a hundred years ago.

The younger two sons took to Engineering. The second son, Kalaichelvan, is Program Manager at Creation Technologies, an award-winning global electronics manufacturing service provider. And the youngest, Dhaksayan, is the Chief Information Officer (CIO) at the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC), which is North America’s third-largest urban transit system.

All three have done their parents proud and Shan would have been gratified to see them achieve exemplary success in their chosen fields. A first class Engineer and a first class teacher, Shan was also a great father and a loving grandfather. As we remember Professor Shanmuganyagam, we extend our thoughts and sympathies to his beloved wife Kalamathy, his sons and their young families

by Rajan Philips

Opinion

Cannavarella: Estate once owned by OEG with a heritage since 1880

Established in 1880, Cannavarella Estate stands among the most historically significant plantations in Sri Lanka, carrying a legacy that intertwines agricultural heritage, colonial transitions and modern development. Its story begins with the cultivation of cinchona, a medicinal bark used to produce quinine, which is a vital treatment for malaria at the time, introduced when coffee estates across the island were failing.

Under the ownership of Messrs Macfarlane, Cannavarella rapidly gained a reputation for producing cinchona at ideal elevations between 4,000 and 5,000 feet above sea level. At that time, the estate spanned around 750 acres and played a pivotal role in the island’s shift from coffee to alternative plantation crops during the late 19th century.

A transformative chapter began when Christopher B. Smith purchased the property and unified several surrounding estates- Moussagolla, Cannavarella, East Gowerakelle, and Naminacooly- into what became known as the Cannavarella Group. This amalgamation created a vast holding of approximately 1,800 acres. By 1915, nearly 1,512 acres of this extent were cultivated in tea, marking the estate’s full transition from cinchona to the crop that would define its identity for generations.

The Group was managed by the Eastern Produce and Estates Company from 1915 until 1964, after which stewardship passed successively to Walker & Sons Company Ltd, and then to George Steuart Company Ltd by 1969.

A defining moment in the estate’s history arrived in 1971 when Sir Oliver Goonetilleke, former Governor General of Ceylon, acquired the estate. Under his ownership, it came under the London-based company Ceyover Ltd., a name derived from “Cey” for Ceylon and “Over” for Oliver.

The estate remained under private ownership until the nationalization wave of 1975, during which Cannavarella was brought under the Janatha Estates Development Board (JEDB). For nearly two decades it was managed under government purview until the plantation sector was re-privatised in 1992.

Thereafter, Cannavarella Estate moved under the management of Namunukula Plantations Limited, first through BC Plantation Services, then under John Keells Holdings’ Keells Plantation Management Services and eventually under the ownership of Richard Pieris & Company PLC, where it continues today as part of the Arpico Plantations portfolio.

Blending heritage, landscape and community

Situated along the northeastern slopes of the scenic Kabralla-Moussagolla range and bordering the Namunukula mountain range, Cannavarella Estate spans a total extent of 800 hectares. Its six divisions rise across elevations from 910 to 1,320 metres above sea level, creating a landscape ideal for cultivating premium high-grown tea. Of the total land area, 351 hectares are dedicated to mature tea, while 54 hectares consist of VP tea, representing 16 % of the estate.

Among its most remarkable features are fields containing seedling tea bushes more than a century old, living symbols of Sri Lanka’s plantation legacy that continue to thrive across the slopes. The estate is also home to the origin of the Menik River, which begins its journey in the Moussagolla Division, adding an ecological richness to Cannavarella’s natural environment.

Cannavarella’s history of leadership reflects broader transformations within the plantation industry. The last English superintendent, Mr. Charles Edwards, oversaw the estate during the final phase of British management. In 1972, he was succeeded by Franklin Jacob, who became the first Sri Lankan superintendent of the Cannavarella Group, marking a shift toward local leadership and expertise in plantation management.

Development within Cannavarella Estate has never been confined to agriculture alone. Over the past decade, the estate has strengthened its emphasis on community care, diversification and improving living conditions for its workers. In 2022, coffee planting was initiated in Fields 7 and 8 of the NKU Division, covering 2.5 hectares as part of a broader effort to introduce alternative revenue streams while complementing tea cultivation.

The estate’s commitment to early childhood development is reflected in the initiation of a morning meal programme across all Child Development Centres from 2025, ensuring that children receive nutritious meals each day. A newly constructed Child Development Centre in the EGK Division, completed in 2020, now offers modern facilities including a play area, study room and kitchen, symbolizing the estate’s dedication to nurturing the next generation. In 2015, a housing scheme consisting of 23 new homes was completed and handed over to workers in the CVE Division, significantly improving quality of life and providing families with safer, more stable living environments.

A future built on stability and renewal

Cannavarella Estate is preparing to undertake one of its most important social development initiatives. A major housing programme has been proposed to relocate 69 families currently residing in landslide-prone areas of the Moussagolla Division. Supported by the Indian Housing Programme, this effort aims to provide secure, sustainable housing in safer terrain, ensuring long-term stability for vulnerable families and reducing disaster risk in the region.

Across its history, Cannavarella Estate has remained a landscape shaped both by the land and the people who call it home. Cannavarella continues to honour its roots while building a modern legacy that uplifts both the estate and its people. (Planters Association news release)

-

Features3 days ago

Features3 days agoMy experience in turning around the Merchant Bank of Sri Lanka (MBSL) – Episode 3

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoZone24x7 enters 2026 with strong momentum, reinforcing its role as an enterprise AI and automation partner

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoRemotely conducted Business Forum in Paris attracts reputed French companies

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoFour runs, a thousand dreams: How a small-town school bowled its way into the record books

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoComBank and Hayleys Mobility redefine sustainable mobility with flexible leasing solutions

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoHNB recognized among Top 10 Best Employers of 2025 at the EFC National Best Employer Awards

-

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoGREAT 2025–2030: Sri Lanka’s Green ambition meets a grid reality check

-

Editorial6 days ago

Editorial6 days agoAll’s not well that ends well?